Louis XIV as an infant with his nurse Longuet de la Giraudière

Statuette of a parclose representing a woman who presses her breast to collect milk in a bowl. – Stalls (16th century) of the Basilica of Saint Materne (11th century) – Walcourt (Belgium).

A wet nurse is a woman who breast feeds and cares for another's child.

Wet nurses are employed if the mother dies, or if she is unable or

elects not to nurse the child herself. Wet-nursed children may be known

as "milk-siblings", and in some cultures the families are linked by a

special relationship of milk kinship. Mothers who nurse each other's babies are engaging in a reciprocal act known as cross-nursing or co-nursing. Wetnursing existed in cultures around the world until the invention of reliable formula milk in the 20th century.

Reasons

A wet nurse can help when a mother is unable or unwilling to feed her baby. Before the development of infant formula in the 20th century, when a mother was unable to breastfeed, a wetnurse was the only way to save the baby's life.

There are many reasons why a mother is unable to produce sufficient breast milk, or in some cases to lactate

at all. Reasons include the serious or chronic illness of the mother

and her treatment which creates a temporary difficulty to nursing.

Additionally, a mother's taking drugs (prescription or recreational) may

necessitate a wet nurse if a drug in any way changes the content of the

mother's milk.

There was also an increased need for wetnurses when the rates of infant abandonment by mothers, and maternal death during childbirth, were high.

Some women choose not to breastfeed for social reasons. Many of

these women were found to be of the upper class. For them,

breastfeeding was considered unfashionable, in the sense that it not

only prevented these women from being able to wear the fashionable

clothing of their time but it was also thought to ruin their figures.

Mothers also lacked the support of their husbands to breastfeed their

children, since hiring a wet nurse was less expensive than having to

hire someone else to help run the family business and/or take care of

the family household duties in their place. Some women chose to hire wet nurses purely to escape from the confining and time-consuming chore of breastfeeding.

Wet nurses have also been used when a mother cannot produce sufficient

breast milk, i.e., the mother feels incapable of adequately nursing her

child, especially following multiple births.

Eliciting milk

A woman can only act as a wet-nurse if she is lactating

(producing milk). It was once believed that a wet-nurse must have

recently undergone childbirth. This is not necessarily the case, as

regular breast suckling can elicit lactation via a neural reflex of prolactin production and secretion. Some adoptive mothers have been able to establish lactation using a breast pump so that they could feed an adopted infant.

Dr Gabrielle Palmer states:

There is no medical reason why women should not lactate indefinitely or feed more than one child simultaneously (known as 'tandem feeding')... some women could theoretically be able to feed up to five babies.

Historical and cultural practices

Wet nursing is an ancient practice, common to many cultures. It has been linked to social class, where monarchies, the aristocracy, nobility

or upper classes had their children wet-nursed for the benefit of the

child's health, and sometimes in the hope of becoming pregnant again

quickly. Exclusive breastfeeding inhibits ovulation in some women (Lactational amenorrhea). Poor women, especially those who suffered the stigma of giving birth to an illegitimate child, sometimes had to give their baby up temporarily to a wet nurse, or permanently to another family.

The woman herself might in turn become wet nurse to a wealthier family,

while using part of her wages to pay her own child's wet nurse. From

Roman times and into the present day, philosophers and thinkers alike

have held the view that the important emotional bond between mother and

child is threatened by the presence of a wet nurse.

Mythology

Many cultures feature stories, historical or mythological, involving superhuman, supernatural, human and in some instances animal wet-nurses.

The Bible refers to Deborah, a nurse to Rebekah wife of Isaac and mother of Jacob (Israel) and Esau, who appears to have lived as a member of the household all her days. (Genesis 35:8.) Midrashic commentaries on the Torah hold that the Egyptian princess Bithiah (Pharaoh's wife Asiya in the Islamic Hadith and Qur'an) attempted to wet-nurse Moses, but he would take only his biological mother's milk. (Exodus 2:6–9)

In Greek mythology, Eurycleia is the wet-nurse of Odysseus. In Roman mythology, Caieta was the wet-nurse of Aeneas. In Burmese mythology, Myaukhpet Shinma is the nat (spirit) representation of the wet nurse of King Tabinshwehti. In Hawaiian mythology, Nuakea is a beneficent goddess of lactation; her name became the title for a royal wetnurse, according to David Malo.

Ancient Rome

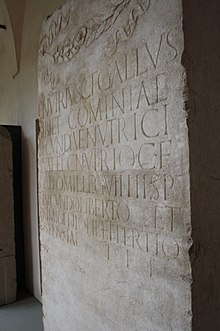

A funerary stele

(akin to a gravestone) erected by Roman citizen Lucius Nutrius Gallus

in the 2nd half of 1st century AD for himself, his wetnurse, and other

members of his family and household

In ancient Rome, well-to-do households would have had wet-nurses (Latin nutrices, singular nutrix) among their slaves and freedwomen, but some Roman women were wet-nurses by profession, and the Digest of Roman law even refers to a wage dispute for wet-nursing services (nutricia). The landmark known as the Columna Lactaria ("Milk Column") may have been a place where wet-nurses could be hired. It was considered admirable for upperclass women to breastfeed their own children, but unusual and old-fashioned in the Imperial era. Even women of the working classes or slaves might have their babies nursed, and the Roman-era Greek gynecologist Soranus offers detailed advice on how to choose a wet-nurse. Inscriptions such as religious dedications and epitaphs indicate that a nutrix would be proud of her profession. One even records a nutritor lactaneus, a male "milk nurse" who presumably used a bottle. Greek nurses were preferred, and the Romans believed that a baby who had a Greek nutrix could imbibe the language and grow up speaking Greek as fluently as Latin.

The importance of the wet nurse to ancient Roman culture is indicated by the founding myth of Romulus and Remus, who were abandoned as infants but nursed by the she-wolf, as portrayed in the famous Capitoline Wolf bronze sculpture. The goddess Rumina was invoked among other birth and child development deities to promote the flow of breast milk.

England

Catherine Willoughby, formerly Duchess of Suffolk, and her later husband Richard Bertie, are forced into exile, taking their baby and wetnurse. Wet nursing was commonplace in England.

Wet-nursing was a well-paid, respectable and popular job for many

lower class women in England. In 17th- and 18th-century England, a

woman would earn more money as a wet nurse than her husband could as a

labourer. Up until the 19th century, most wet-nursed infants were sent

far from their families to live with their wet nurse for up to the first

three years of their life.

As many as 80% of wet-nursed babies who lived with their wet nurses

died during infancy, which led to a change in living conditions.

Women took in babies for money in Victorian Britain, and nursed them themselves or fed them with whatever was cheapest. This was known as baby-farming; poor care sometimes resulted in high infant death rates. The wet nurse at this period was most likely a single woman who previously had given birth to an illegitimate child.

There were two types of wet nurses in Victorian England. There were

those on poor relief, who struggled to provide sufficiently for

themselves or their charges, and there were professional wet nurses who

were well paid and respected.

It was common for upper-class women to hire wet nurses to

breastfeed their children. English women tended to work within their

employers' homes to take care of their charge, as well as working at foundling hospitals

for abandoned children. The wet nurse's own child would likely be sent

out to nurse, normally brought up by the bottle rather than being

breastfed. Valerie Fildes, author of Breasts, Bottle and Babies: A History of Infant Feeding, argues that "In effect, wealthy parents frequently 'bought' the life of their infant for the life of another."

Wet nursing in England decreased in popularity during the

mid-19th century due to the writings of medical journalists concerning

the undocumented dangers of wet nursing. Valerie Fildes argued that

"Britain has been lumped together with the rest of Europe in any

discussion of the qualities, terms of employment and conditions of the

wet nurse, and particularly the abuses of which she was supposedly

guilty."

C. H. F. Routh, a medical journalist writing in the late 1850s in

England, argued that there were many evils of wet-nursing, such as that

wet-nurses were more likely to abandon their own children, there was

increased mortality for children under the charge of a wet-nurse, and an

increased physical and moral risk to a nursed child.

While this argument was not founded in any sort of proof, the emotional

arguments of medical researchers, coupled with the protests of critics

of the practice slowly increased public knowledge and brought

wet-nursing into obscurity, replaced by maternal breastfeeding and

bottle-feeding.

France

The bureau of wet nurses in Paris

Wet nursing was reported in France in the time of Louis XIV,

the mid 17th century. In 18th century France, approximately 90% of

infants were wet nursed, mostly sent away to live with their wet nurses. In Paris in 1780, only 1000 of the 21,000 babies born that year were nursed by their own mother.

The high demand for wet nurses coincided with the low wages and high

rent prices of this era, which forced many women to have to work soon

after childbirth.

This meant that many mothers had to send their infants away to be

breastfed and cared for by wet nurses even poorer than themselves. With

the high demand for wet nurses, the price to hire one increased as the

standard of care decreased.

This led to many infant deaths. In response, rather than nursing their

own children, upper class women turned to hiring wet nurses to come live

with them instead. In entering into their employers home to care for

their charges, these wet nurses had to leave their own infants to be

nursed and cared for by women far worse off than themselves, and who

likely lived at a relatively far distance away.

The Bureau of Wet Nurses was created in Paris, 1769, to serve two

main purposes; it supplied parents with wet nurses, as well as helped

lessen the neglect of charges by controlling monthly salary payments to

wet nurses.

In order to become a wet nurse, women had to meet a few qualifications

including a good physical body with a good moral character, they were

often judged on their age, their health, the number of children they

had, as well as their breast shape, breast size, breast texture, nipple

shape and nipple size, since all these aspects were believed to affect

the quality of a woman's milk.

In 1874, the French government introduced the Roussel Law, which

"mandated that every infant placed with a paid guardian outside the

parents' home be registered with the state so that the French government

is able to monitor how many children are placed with wet nurses and how

many wet nursed children have died".

Wet nurses were often hired to work in hospitals so that they

could nurse premature babies, babies who were ill, or babies who had

been abandoned. During the 18th and 19th centuries, congenital syphilis was a common cause of infant mortality in France.

The Vaugirard hospital in Paris began to use mercury as a treatment for

syphilis; however, it could not be safely administered to infants.

In 1780, began the process of giving mercury to wet nurses who could

then transmit the treatment to the infants with syphilis through their

milk in the act of breastfeeding.

The practice of wetnursing was still widespread during World War I, according to the American Red Cross. Working class women would leave their babies with wetnurses so they could get jobs in factories.

United States

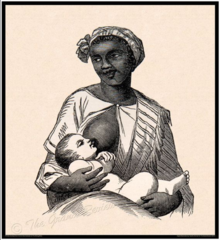

Enslaved Black woman wet-nursing White infant

English colonists brought the practice of wet nursing with them to North America.

Since the arrangement of sending infants away to live with wet nurses

was the cause of so many infant deaths, by the 19th century, Americans

adopted the practice of having wet nurses live with the employers in

order to nurse and care for their charges.

This practice had the effect of increasing the death rate for wet

nurses' own babies. Many employers would have only kept a wet nurse for a

few months at a time since it was believed that the quality of a

woman's breast milk would lessen over time.

Since there were no official records kept pertaining to wet

nurses or wet nursed children in the United States, historians lack the

knowledge of precisely how many infants were wet-nursed, for how long

they were wet-nursed, whether they lived at home or else where while

they wet-nursed, as well as how many wet-nursed babies lived or died.

The only evidence which exists pertaining to wet-nursing in the United

States is found in the help wanted ads of newspapers, through complaints

about wet nurses in magazines, and through medical journals which acted

as employment agencies for wet-nurses.

In the Southern United States, it was common practice for

enslaved black women to be forced to be wet nurses to their owner's

children. In some instances, the enslaved child and the white child would be raised together in their younger years. Visual representations of wet-nursing practices in enslaved communities are most prevalent in representations of the Mammy archetype caricature.

Images such as the one in this section represent both a historically

accurate practice of enslaved Black women wet-nursing their owner's

white children as well as sometimes an exaggerated racist

caricaturization of a stereotype of enslaved Black women as "Mammy"

characters.

Relationships

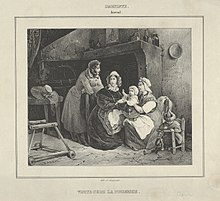

"Visite Chez la Nourrice" ("Visit to the Wetnurse") by Victor Adam

An infant who has been living with a wet-nurse being taken away from its foster-parents by its natural mother. By Étienne Aubry

Sometimes the infant is placed in the home of the wetnurse for several months, as was the case for Jane Austen and her siblings. The Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 91, a receipt from 187 AD,

attests to the ancient nature of this practice. Sometimes the wetnurse

came to live with the infant's family, filling a position between the monthly nurse (for the immediate post-partum period) and the nanny.

In some cultures the wetnurse is simply hired as any other

employee. In others, however, she has a special relationship with the

family, which may incur kinship rights. In Vietnamese family structure, for example, the wetnurse is known as Nhũ mẫu, mẫu meaning "mother". Islam has a highly codified system of milk kinship known as rada. George III of the United Kingdom, born two months premature, had a wet nurse whom he so valued all his life that her daughter was appointed laundress to the Royal Household, "a sinecure place of great emolument".

Current attitudes in Western countries

In

contemporary affluent Western societies such as the United States, the

act of nursing a baby other than one's own often provokes cultural

discomfort. When a mother is unable to nurse her own infant, an

acceptable mediated substitute is expressed milk (or especially colostrum) which is donated to milk banks, analogous to blood banks, and processed there by being screened, pasteurized, and usually frozen. Infant formula

is also widely available, which its makers claim can be a reliable

source of infant nutrition when prepared properly. Dr Rhonda Shaw notes

that Western objections to wet-nurses are cultural:

The exchange of body fluids between different women and children, and the exposure of intimate bodily parts make some people uncomfortable. The hidden subtext of these debates has to do with perceptions of moral decency. Cultures with breast fetishes tend to conflate the sexual and erotic breast with the functional and lactating breast.

In addition, the legacy of wet-nursing for African-American women is

inherently linked to slavery, and the physical, emotional, and mental

abuse that enslaved African-American women endured. While other

populations in the United States may be more open to wet-nursing,

the cultural attitude within African-American communities towards

wet-nursing remains one deeply affected by the generational trauma of

wet-nursing during slavery.

For some Americans, the subject of wet-nursing is becoming increasingly open for discussion. During a UNICEF goodwill trip to Sierra Leone in 2008, Mexican actress Salma Hayek

decided to breast-feed a local infant in front of the accompanying film

crew. The sick one-week-old baby had been born the same day but a year

later than her daughter, who had not yet been weaned. Hayek later

discussed on camera an anecdote of her Mexican great-grandmother

spontaneously breast-feeding a hungry baby in a village.

Current situation elsewhere

Wet nurses are still common in many developing countries, although the practice poses a risk of infections such as HIV. In China, Indonesia, and the Philippines, a wet-nurse may be employed in addition to a nanny as a mark of aristocracy, wealth, and high status. Following the 2008 Chinese milk scandal, in which contaminated infant formula poisoned thousands of babies, the salaries of wet-nurses there increased dramatically. The use of a wet-nurse is seen as a status symbol in some parts of modern China.

Additionally, a woman who is difficult to get pregnant may

wet-nurse and rear a relative (especially a poorer one's) new-born as a mancing (Javanese language for "lure").

Notable wetnurses

Royal wetnurses are more likely than most to reach the historical record.

In Ancient Egypt, Maia was the wetnurse of King Tutankhamun. Sitre In, the nurse of Hatshepsut, was not a member of the royal family, but received the honour of a burial in the royal necropolis in the Valley of the Kings in tomb KV60. Her coffin has the inscription sdt nfrw nsw in m3‘t ḥrw, meaning Royal Wet Nurse. Lady Kasuga was the wet nurse of the third Tokugawa shōgun Iemitsu. Lu Lingxuan was a lady in waiting who served as wetnurse to the emperor Gao Wei;

she became exceedingly powerful during his reign, and was often

criticized by historians for her corruption and treachery. Chinese

emperors honoured the Nurse Empress Dowager. Dai Anga was the wetnurse of the Mughal Emperor, Shah Jahan. Shin Myo Myat was the mother of King Bayinnaung of Toungoo Dynasty of Burma (Myanmar), and the wetnurse of King Tabinshwehti. In England, Hodierna of St Albans was the mother of Alexander Neckam and wet nurse of Richard I of England, and Mrs. Pack was a wet nurse to William, Duke of Gloucester (1689–1700).

Some non-royal wetnurses have been written about. Halimah bint Abi Dhuayb was the foster-mother and wetnurse of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Petronella Muns was, with her employer, the first Western woman to visit Japan. Naomi Baumslag, author of Milk, Money and Madness, described the legendary capacity of Judith Waterford:

"In 1831, on her 81st birthday, she could still produce breast milk. In

her prime she unfailingly produced two quarts (four pints or 1.9

litres) of breast milk a day."