Playfulness by Paul Manship

Play is a range of voluntary, intrinsically motivated activities done for recreational pleasure and enjoyment.

Play is commonly associated with children and juvenile-level

activities, but play occurs at any life stage, and among other

higher-functioning animals as well, most notably mammals.

Many prominent researchers in the field of psychology, including Melanie Klein, Jean Piaget, William James, Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung and Lev Vygotsky

have viewed play as confined to the human species, believing play was

important for human development and using different research methods to

prove their theories.

Play is often interpreted as frivolous; yet the player can be

intently focused on their objective, particularly when play is

structured and goal-oriented, as in a game. Accordingly, play can range from relaxed, free-spirited and spontaneous through frivolous to planned or even compulsive.

Play is not just a pastime activity; it has the potential to serve as

an important tool in numerous aspects of daily life for adolescents,

adults, and cognitively advanced non-human species (such as primates).

Not only does play promote and aid in physical development (such as hand-eye coordination),

but it also aids in cognitive development and social skills, and can

even act as a stepping stone into the world of integration, which can be

a very stressful process. Play is something that most children partake

in, but the way play is executed is different between cultures and the

way that children engage with play varies universally.

Definitions

The seminal text in the field of play studies is the book Homo Ludens first published in 1944 with several subsequent editions, in which Johan Huizinga defines play as follows:

Summing up the formal characteristic of play, we might call it a free activity standing quite consciously outside 'ordinary' life as being 'not serious' but at the same time absorbing the player intensely and utterly. It is an activity connected with no material interest, and no profit can be gained by it. It proceeds within its own proper boundaries of time and space according to fixed rules and in an orderly manner. It promotes the formation of social groupings that tend to surround themselves with secrecy and to stress the difference from the common world by disguise or other means.

This definition of play as constituting a separate and independent

sphere of human activity is sometimes referred to as the "magic circle"

notion of play, a phrase also attributed to Huizinga.

Many other definitions exist. Jean Piaget stated, "the many theories of

play expounded in the past are clear proof that the phenomenon is

difficult to understand."

There are multiple aspects of play people home in on when defining it. One definition from Susanna Millar's The Psychology of Play

defines play as: “any purposeful mental or physical activity performed

either individually or group-wise in leisure time or at work for

enjoyment, relaxation, and satisfaction of real-time or long term

needs.”

This definition particularly emphasizes the conditions and benefits to

be gained under certain actions or activities related to play. Other

definitions may focus on play as an activity that must follow certain

characteristics including willingness to engage, uncertainty of the

outcome, and productivity of the activity to society.

Another definition of play from the twenty-first century comes

from the National Playing Fields Association (NPFA). The definition

reads as follows: “play is freely chosen, personally directed,

intrinsically motivated behaviour that actively engages the child.” This definition focuses more on the child's freedom of choice and personal motivation related to an activity.

Forms

People having fun

Play can take the form of improvisation or pretense, interactive,

performance, mimicry, games, sports, and thrill-seeking, such as extreme

or dangerous sports (sky-diving, high-speed racing, etc.). Philosopher Roger Caillois wrote about play in his 1961 book Man, Play and Games and Stephen Nachmanovitch expanded on these concepts in his 1990 book Free Play: Improvisation in Life and Art. Nachmanovitch writes that:

Improvisation, composition, writing, painting, theater, invention, all creative acts are forms of play, the starting place of creativity in the human growth cycle, and one of the great primal life functions. Without play, learning and evolution are impossible. Play is the taproot from which original art springs; it is the raw stuff that the artist channels and organizes with all his learning and technique. (Free Play, p. 42)

Free play gives children the freedom to decide what they want to play

and how it will be played. Both the activity and the rules are subject

to change in this form, and children can make any changes to the rules

or objectives of the play at any time.

Some countries in the twenty-first century have added emphasis of free

play into their values for children in early childhood such as Taiwan

and Hungary.

Structured play has clearly defined goals and rules and such play is called a "game". Other play is unstructured or open-ended. Both types of play promote adaptive behaviors and mental states of happiness.

Sports with defined rules will take place within designated play spaces, such as sports fields where, in Soccer

for example, players kick a ball in a certain direction and push

opponents out of their way as they do so. While appropriate within the

sport's play space, these same behaviors might be inappropriate or even

illegal outside the playing field.

Other designed play spaces can be playgrounds

with dedicated equipment and structures to promote active and social

play. Some play spaces go even farther in specialization to bring the

play indoors and will often charge admission as seen at Children's Museums, Science Centers, or Family Entertainment Centers. Family Entertainment Centers (or Play Zones) are typically For-Profit businesses purely for play and entertainment, while Children's Museums and Science Centers are typically Non-Profit organizations for educational entertainment.

The California-based National Institute for Play describes seven play patterns:

- Attunement play, which establishes a connection, such as between newborn and mother.

- Body play, in which an infant explores the ways in which his or her body works and interacts with the world, such as making funny sounds or discovering what happens in a fall.

- Object play, such as playing with toys, banging pots and pans, handling physical things in ways that use curiosity.

- Social play, play which involves others in activities such as tumbling, making faces, and building connections with another child or group of children.

- Imaginative or pretend play, in which a child invents scenarios from his or her imagination and acts within them as a form of play, such as princess or pirate play.

- Storytelling play, the play of learning and language that develops intellect, such as a parent reading aloud to a child, or a child retelling the story in his or her own words.

- Creative play, by which one plays with imagination to transcend what is known in the current state, to create a higher state. For example, a person might experiment to find a new way to use a musical instrument, thereby taking that form of music to a higher plane; or, as Einstein was known to do, a person might wonder about things which are not yet known and play with unproven ideas as a bridge to the discovery of new knowledge.

Separate from self-initiated play, play therapy

is used as a clinical application of play aimed at treating children

who suffer from trauma, emotional issues and other problems.

Children

In young children, play is frequently associated with cognitive development and socialization. Play that promotes learning and recreation often incorporates toys, props, tools or other playmates.

Play can consist of an amusing, pretend or imaginary activity alone or

with another. Some forms of play are rehearsals or trials for later life

events, such as "play fighting", pretend social encounters (such as

parties with dolls), or flirting. Modern findings in neuroscience

suggest that play promotes flexibility of mind, including adaptive

practices such as discovering multiple ways to achieve a desired result,

or creative ways to improve or reorganize a given situation (Millar,

1967; Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000).

Children playing in a sandbox

As children get older, they engage in board games, video games and computer play, and in this context the word gameplay is used to describe the concept and theory of play and its relationship to rules and game design. In their book, Rules of Play,

researchers Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman outline 18 schemas for

games, using them to define "play", "interaction" and "design" formally

for behaviorists. Similarly, in his book Half-Real: Video Games between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds,

game researcher and theorist Jesper Juul explores the relationship

between real rules and unreal scenarios in play, such as winning or

losing a game in the real world when played together with real-world

friends, but doing so by slaying a dragon in the fantasy world presented

in the shared video game.

Play is explicitly recognized in Article 31 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations, November 29, 1989), which declares:

- Parties recognize the right of the child to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts.

- Parties shall respect and promote the right of the child to participate fully in cultural and artistic life and shall encourage the provision of appropriate and equal opportunities for cultural, artistic, recreational and leisure activities.

Children's Games, 1560, Pieter Bruegel the Elder

History of childhood playtime

American historian Howard Chudacoff has studied the interplay between parental control of toys

and games and children's drive for freedom to play. In the colonial

era, toys were makeshift and children taught each other very simple

games with little adult supervision. The market economy of the 19th

century enabled the modern concept of childhood as a distinct, happy

life stage. Factory-made dolls and doll houses delighted young girls.

Organized sports filtered down from adults and colleges, and boys

learned to play with a bat, a ball and an impromptu playing field. In

the 20th century, teenagers were increasingly organized into club sports

supervised and coached by adults, with swimming taught at summer camps and through supervised playgrounds. Under the New Deal's Works Progress Administration, thousands of local playgrounds and ball fields opened, promoting softball especially as a sport for all ages and both sexes.

By the 21st century, Chudacoff notes, the old tension between parental

controls and a child's individual freedom was being played out in cyberspace.

Cultural differences of play

Museum of toys – Portugal

The act of play time is a cross-cultural phenomenon that is

universally accepted and encouraged by most communities however it can

differ in the ways that is performed.

Some cultures, such as Euro-American cultural heritages,

encourage play time in order to stress cognitive benefits and the

importance of learning how to care for one's self. Other cultures, such

as people of African American or Asian American heritages, stress more

group oriented learning and play where kids can learn what they can do

with and for others.

Parent interactions when it comes to playtime also differs drastically

within communities. Parents in the Mayan culture do interact with their

children in a playful mindset while parents in the United States tend to

set aside time to play and teach their children through games and

activities. In the Mayan community, children are supported in their

playing but also encouraged to play while watching their parents do

household work in order to become familiar with how to follow in their

footsteps.

Elephant – Mud play

All around the world, children use different natural materials like

stones, water, sand, leaves, fruits, sticks and a variety of resources

to play. In addition, there are groups that have access to crafts,

industrialized toys, electronics and video-games.

In Australia, games and sports are part of play. There, play can

be considered as preparation for life and self- expression, like in many

other countries.

Groups of children in Efe of the Democratic Republic of Congo can

be seen making ‘food’ from dirt or pretending to shoot bows and arrows

much like their elders. These activities are similar to other forms of

play worldwide. For instance, children can be seen comforting their toy

dolls or animals, anything that they have modeled from adults in their

communities.

In Brazil, we can find children playing with balls, kites,

marbles, pretend houses or mud kitchens, like in many other countries.

In smaller communities they use mud balls, little stones or cashews to

replace marbles.

Child playing around the kitchen

At an indigenous community of Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in

Colombia, children's play is highly valued and encouraged by leaders and

parents. They interact with the children of different ages and explore

together different environments to let the children express themselves

as part of the group.

Some children in the Sahara use clay figures as their forms of

playful toys. Toys in general are a representation of cultural

practices. They usually illustrate characters and objects of a

community.

Play time can be used as a way for children to learn the

different ways of their culture. Many communities use play to can

emulate work. The way in which children mimic work through their play

can differ according to the opportunities they have access to, but it is

something that tends to be promoted by adults.

Sports

Sportive

activities are one of the most universal forms of play. Different

continents have their own popular/dominant sports. For example, European, South American, and African countries enjoy soccer (also known as ‘football’ in Europe), while North American countries prefer basketball, ice hockey, baseball, or American football. In Asia, sports such as table tennis and badminton are played professionally; however soccer and basketball are played amongst common folks. Events such as The Olympic Games and FIFA World Cup showcase countries competing with each other and are broadcast all over the world.

Sports can be played as a leisure activity or within a competition. According to sociologist Norbert Elias; it is an important part of "civilization process". Victory and defeat in sports can also influence one's emotions to a point where everything else seems so irrelevant. Sport fans can also imagine what it feels like to play for their preferred team. The feelings people experience can be so surreal that it affects their emotions and behavior.

Benefits in youth

Youth

sport can provide a positive outcome for youth development. Research

shows adolescents are more motivated and engaged in sports than any

other activity, and these conditions predict a richer personal and interpersonal development. Anxiety, depression and obesity can stem from lack of activity and social interaction. There is a high correlation between the amount of time that youth spend playing sports and the effects of physical (e.g., better general health), psychological (e.g., subjective well being), academic (e.g., school grades), and social benefits (e.g., making friends).

Electronics over the past 10 years have been looked as a form of

playtime but researchers have found that most electronic play leads to

lack of motivation, no social interaction and can lead to obesity.

Play is originally based on the idea of children using their creativity

while developing their imagination, dexterity, physical, cognitive and

emotional strength. Dramatic play is common in younger children. For the youth community to benefit from playtime, the following are recommended:

- Give children ample, unscheduled time to be creative to reflect and decompress

- Give children “true” toys, such as blocks or dolls for creativity

- Youth should have a group of supportive people around them (teammates, coaches, and parents) with positive relationships

- Youth should possess skill development; such as physical, interpersonal, and knowledge about the sport

- Youth should be able to make their own decisions about their sport participation

- Youth should have experiences that are on par with their certain needs and developmental level

Research findings on benefits in youth

With

regular participation in a variety of sports, children can develop and

become more proficient at various sports skills (including, but not

limited to, jumping, kicking, running, throwing, etc.) if the focus is on skill mastery and development. Young people participating in sports also develop agility, coordination, endurance, flexibility, speed, and strength. More specifically, young athletes could develop the following:

- enhanced functioning and health of Cardiorespiratory and Muscular systems

- improved flexibility, mobility, and coordination

- increased stamina and strength

- increased likelihood of maintaining weight

Moreover, research shows that regular participation in sport and

physical activity is highly associated with lowering the risk of diabetes, heart disease, obesity,

and other related diseases. Young people also tend to be more

nutrition-conscious in their food choices when participating in sport Girls involved in sport tend associate with lower chance of teenage pregnancy, begin smoking, and/or developing breast cancer. Young athletes have shown lower levels of total cholesterol and other favorable profiles in serum lipid parameters associated with cardiovascular disease.

Sport provides an arena for young people to be physically active and in

result reduce the time spent in sedentary pursuits, such as watching TV and playing video games.

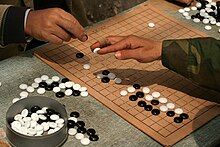

Adults

Playing weiqi in Shanghai

Although adults who engage in excessive amounts of play may find

themselves described as "childish" or "young at heart" by less playful

adults, play is actually an important activity, regardless of age.

Creativity and happiness can result from adult play, where the objective

can be more than fun alone, as in adult expression of the arts, or

curiosity-driven science.

Some adult "hobbies" are examples of such creative play. In creative

professions, such as design, playfulness can remove more serious

attitudes (such as shame or embarrassment) that impede brainstorming or

artistic experimentation in design.

Imaginative play and role play may allow adult individuals to practice useful habits such as learned optimism, which is helpful in managing fear or terrors.

Play also offers adults the opportunity to practice concepts that may

not have been explicitly or formally taught (e.g. how to manage

misinformation or deceit). Thus, even though play is just one of many

tools used by effective adults, it remains a necessary one.

Workplace

There has been extensive research when it comes to the benefits of play amongst children, youth, and adolescence.

Most commonly overlooked are the benefits of play for adults, more

specifically, adults who spend a lot of time in the workplace. Many

adults in North America are in the workforce and spend half of their

waking hours in a workplace environment with little to no time for play.

Play in this context refers to leisure-type activities with colleagues

during lunch breaks or short breaks throughout the working day. Leisure

activities could include, but are not limited to, different forms of

physical sport activities, card games, board games, video games and interaction-based type video games, foosball, ping-pong, yoga, and boot-camp sessions.

Research shows that playing games may promote a persistent and optimistic motivational style and positive affect. Positive affect enhances people's experiences, enjoyment, and sense of satisfaction

derived from the activity, during their engagement with a certain task.

While people are engaged in their work, positive affect increases the

satisfaction they feel from the work, and this has also been shown to

increase their creativity and improve their performance on problem-solving tasks as well as other tasks. The development of a persistent motivational style charged with positive affect may lead to lasting work success.

Studies show that work and play are mutually supportive. Employees need to experience the sense of newness, flow, discovery

and liveliness that play provides. By doing this, it will provide the

employee with the sense that they are integrated within the

organization, and therefore they will feel and perform better.

By incorporating play at work, it will also result in more productivity, creativity and innovation, higher job satisfaction, greater workplace morale, stronger or new social bonds, improved job performance, a decrease in staff turnover, absenteeism and stress. Decreased stress leads to less illness, which results in lower health care costs.

Play at work may help employees function and cope when under stress,

refresh body and mind, encourage teamwork, trigger creativity, and

increase energy while preventing burnout.

Studies show that companies that encourage play at work, whether

short breaks throughout the day or during lunch breaks experience more

success because it leads to positive emotion amongst employees. Risk

taking, confidence in presenting novel ideas, and embracing unusual and

fresh perspectives are common characteristics associated with play at

work.

Play can increase self-reported job satisfaction and well-being.

Employees experiencing positive emotions are more cooperative, more

social, and perform better when faced with complex tasks.

Contests, team-building exercises, fitness programs, mental

health breaks and other social activities, will make the work

environment fun, interactive, and rewarding.

Also playfighting, i.e. playful fights or fictive disputes, may

contribute to organizations and institutions, as in youth care settings.

Staff tries to down-key playfight invitations to “treatment” or

“learning,” but playfighting also offers youth and staff identificatory

respite from the institutional regime. Wästerfors (2016) has found that

playfighting is a recurrent pattern in the social life of a youth care

institution and sits at the core of what inmates and staff have to deal

with

Seniors

Older adults represent one of the fastest growing populations around the world. In fact, the United Nations predicted an increase of those aged 60 and above from 629 million in 2002 to approximately two billion in 2050 but increased life expectancy does not necessarily translate to a better quality of life. For this reason, research has begun to investigate methods to maintain and/or improve quality of life among older adults.

Similar to the data surrounding children and adults, play and

activity are associated with improved health and quality of life among

seniors. Additionally, play and activity tend to affect successful aging as well as boost well-being throughout the lifespan.

Although children, adults, and seniors all tend to benefit from play,

older adults often perform it in unique ways to account for possible

issues, such as health restrictions, limited accessibility, and revised

priorities. For this reason, elderly people may partake in physical exercise groups, interactive video games, and social forums specifically geared towards their needs and interests. One qualitative research study found older adults often chose to engage in specific games such as dominoes, checkers, and bingo for entertainment.

Another study indicated a common pattern within game preferences among

older adults; seniors often favor activities that encourage mental and

physical fitness, incorporate past interests, have some level of

competition, and foster a sense of belonging.

Researchers investigating play in older adults are also interested in

the benefits of technology and video games as therapeutic tools. Studies

show these outlets can lower the risk of developing particular

diseases, reduce feelings of social isolation and stress, as well as promote creativity and the maintenance of cognitive skills. As a result, play has been integrated into physiotherapy and occupational therapy interventions for seniors.

The ability to incorporate play into one's routine is important

because these activities allow participants to express creativity, improve verbal and non-verbal intelligence as well as enhance balance.

These benefits may be especially crucial to seniors because evidence

shows cognitive and physical functioning declines with age.

However, other research argues it might not be aging that is associated

with the decline in cognitive and physical capabilities. More

specifically, some studies indicate it could be the higher levels of

inactivity within older adults that may have significant ramifications

on their health and well-being.

With attention to these hypotheses, research shows play and activity tend to decline with age which may result in negative outcomes such as social isolation, depression, and mobility issues. American studies found that only 24% of seniors took part in regular physical activity and only 42% use the internet for entertainment purposes.

In comparison to other age groups, the elderly are more likely to

experience a variety of barriers, such as difficulty with environmental

hazards and accessibility related issues, that may hinder their

abilities to execute healthy play behaviours.

Similarly, although playing may benefit seniors, it also has the

potential to negatively impact their health. For example, those who play

may be more susceptible to injury.

Investigating these barriers may assist in the creation of useful

interventions and/or the development of preventative measures, such as

establishing safer recreational areas, that promote the maintenance of

play behaviours throughout elderly life.

A significant amount of literature suggests a moderate level of

play has numerous positive outcomes in the lives of senior citizens.

In order to support and promote play within the older population,

studies suggest institutions should set up more diverse equipment, improve conditions within recreational areas, and create more video games or online forums that appeal to the needs of seniors.

Animals

Cocker spaniel playing with a monkey doll

Evolutionary

psychologists believe that there must be an important benefit of play,

as there are so many reasons to avoid it. Animals are often injured

during play, become distracted from predators, and expend valuable

energy. In rare cases, play has even been observed between different

species that are natural enemies such as a polar bear and a dog.

Yet play seems to be a normal activity with animals who occupy the

higher strata of their own hierarchy of needs. Animals on the lower

strata, e.g. stressed and starving animals, generally do not play. However, in wild Assamese macaques

physically active play is performed also during periods of low food

availability and even if it is at the expense of growth, which strongly

highlights the developmental and evolutionary importance of play.

The social cognitive complexity of numerous species, including

dogs, have recently been explored in experimental studies. In one such

study, conducted by Alexandra Horowitz of the University of California,

the communication and attention-getting skills of dogs were

investigated. In a natural setting, dyadic play behavior was observed;

head-direction and posture was specifically noted. When one of the two

dogs was facing away or otherwise preoccupied, attention-getting

behaviors and signals (nudging, barking, growling, pawing, jumping,

etc.) were used by the other dog to communicate the intent and/or desire

to continue on with the dyadic play. Stronger or more frequent

signaling was used if the attention of the other dog was not captured.

These observations tell us that these dogs know how play behavior and

signaling can be used to capture attention, communicate intent and

desire, and manipulate one another. This characteristic and skill,

called the "attention-getting skill" has generally only been seen in

humans, but is now being researched and seen in many different species.

Observing play behavior in various species can tell us a lot about the

player's environment (including the welfare of the animal), personal

needs, social rank (if any), immediate relationships, and eligibility

for mating. Play activity, often observed through action and signals,

often serves as a tool for communication and expression. Through

mimicry, chasing, biting, and touching, animals will often act out in

ways so as to send messages to one another; whether it's an alert,

initiation of play, or expressing intent. When play behavior was

observed for a study in Tonkean macaques,

it was discovered that play signals weren't always used to initiate

play; rather, these signals were viewed primarily as methods of

communication (sharing information and attention-getting).

One theory – "play as preparation" – was inspired by the observation that play often mimics adult themes of survival. Predators such as lions and bears play by chasing, pouncing, pawing, wrestling, and biting, as they learn to stalk and kill prey. Prey animals such as deer and zebras

play by running and leaping as they acquire speed and agility. Hoofed

mammals also practice kicking their hind legs to learn to ward off

attacks. Indeed, time spent in physical play accelerates motor skill

acquisition in wild Assamese macaques.

While mimicking adult behavior, attacking actions such as kicking and

biting are not completely fulfilled, so playmates do not generally

injure each other. In social animals, playing might also help to

establish dominance rankings among the young to avoid conflicts as

adults.

John Byers, a zoologist at the University of Idaho,

discovered that the amount of time spent at play for many mammals (e.g.

rats and cats) peaks around puberty, and then drops off. This

corresponds to the development of the cerebellum, suggesting that play is not so much about practicing exact behaviors, as much as building general connections in the brain. Sergio Pellis and colleagues at the University of Lethbridge

in Alberta, Canada, discovered that play may shape the brain in other

ways, too. Young mammals have an overabundance of brain cells in their

cerebrum (the outer areas of the brain – part of what distinguishes

mammals). There is evidence that play helps the brain clean up this

excess of cells, resulting in a more efficient cerebrum at maturity.

Marc Bekoff (a University of Colorado

evolutionary biologist) proposes a "flexibility" hypothesis that

attempts to incorporate these newer neurological findings. It argues

that play helps animals learn to switch and improvise all behaviors more

effectively, to be prepared for the unexpected. There may, however, be

other ways to acquire even these benefits of play: the concept of equifinality.

The idea is that the social benefits of play for many animals, for

example, could instead be garnered by grooming. Patrick Bateson

maintains that equifinality is exactly what play teaches. In accordance

with the flexibility hypothesis, play may teach animals to avoid "false

endpoints". In other words, they will harness the childlike tendency to

keep playing with something that works "well enough", eventually

allowing them to come up with something that might work better, if only

in some situations. This also allows mammals to build up various skills

that could come in handy in entirely novel situations. A study on two species of monkeys Semnopithecus entellus and Macaca mulatta

that came into association with each other during food provisioning by

pilgrims at the Ambagarh Forest Reserve, near Jaipur, India, shows the

interspecific interaction that developed between the juveniles of the

two species when opportunity presented itself.

Development and learning

Learning through play has been long recognized as a critical aspect of childhood and child development. Some of the earliest studies of play started in the 1890s with G. Stanley Hall,

the father of the child study movement that sparked an interest in the

developmental, mental and behavioral world of babies and children. Play

also promotes healthy development of parent-child bonds, establishing

social, emotional and cognitive developmental milestones that help them

relate to others, manage stress, and learn resiliency.

Modern research in the field of affective neuroscience (the neural mechanisms of emotion) has uncovered important links between role play and neurogenesis in the brain. For example, researcher Roger Caillois used the word ilinx

to describe the momentary disruption of perception that comes from

forms of physical play that disorient the senses, especially balance.

Studies have found that play and coping to daily stressors to be positively correlated in children.

By playing, children regulate their emotions and this is important for

adaptive functioning because without regulation, emotions could be

overwhelming and stressful.

Evolutionary psychologists have begun to explore the phylogenetic

relationship between higher intelligence in humans and its relationship

to play, i.e., the relationship of play to the progress of whole

evolutionary groups as opposed to the psychological implications of play

to a specific individual.

Physical, mental and social

Various

forms of play, whether it is physical or mental, have influenced

cognitive abilities in individuals. As little as ten minutes of exercise

(including physical play), can improve cognitive abilities.

These researchers did a study and have developed an "exergame" which is

a game that incorporates some physical movement but is by no means

formal exercise. These games increase one's heart rate to the level of

aerobics exercise and have proven to result in recognizable improvements

in mental faculties.

In this study they use play in a way that incorporates physical activity

that creates physical excursions. The results of the study had

statistical significance. There were improvements in math by 3.4% and

general improvements in recall memory by 4% among the participants of

the study.

On the other hand, other research has focused on the cognitive

effects of mentally stimulating play. Playing video games is one of the

most common mediums of play for children and adults today. There has

been mixed reviews on the effects of video games. Despite this,

according to a research conducted by Hollis (2014),

"[playing video games] was positively associated with skills strongly

related to academic success, such as time management, attention,

executive control, memory, and spatial abilities – when playing video game occurs in moderation".

Play can also influence one's social development and social

interactions. Much of the research focuses on the influence play has on

child social development. There are different forms of play that have

been noted to influence child social development. One study conducted by

(Sullivan, 2003) explores the influence of playing styles with mothers

versus playing styles with fathers and how it influences child social

development. This article explains that "integral to positive

development is the child's social competence or, more precisely, the

ability to regulate their own emotions and behaviors in the social

contexts of early childhood to support the effective accomplishment of

relevant developmental tasks.

Social benefits of play have been measured using basic interpersonal values such as getting along with peers.

One of the social benefits that this researcher has uncovered is that

play with parents has proven to reduce anxiety in children. Having play

time with parents that involves socially acceptable behaviour makes it

easier for children to relate to be more socially adjusted to peers at

school or at play

Social development involving child interaction with peers is thus an

area of influence for playful interactions with parents and peers.

Play in educational practices

Anji play

Anji

play is an educational method based on children's self-directed play in

outside spaces, using simple tools made of natural material. The

teachers and instructors only observe and document the children's

independent play. The method was created by Cheng Xueqin and is

organized in two hours of free play, when the children choose the

available material they want to use and build structures to play.

While planning, experimenting, building and using the structures

to play, the children have the opportunity to interact with peers, to

think critically about what may work, to discuss the plan and organize

the construction hard work. The process is observed and recorded by the

teachers and instructors without intervention, even in instances of

possible risk.

Before and after the two hours of play, the children have the

opportunity to express their plans and discuss with the peers. After the

play, they get the opportunity to draw, write or explain what they did.

Then, they watch the videos recorded the same day and explain how they

played and comment each other's creations.

Anji play is also called “true play” and its guiding principles

are love, risk, joy, engagement and reflection. This method of

self-initiated and self-directed play is applied at the pre-schools (to

children from 3 to 6 years-old) in Anji county, East China.