| |

| Written | c. 1800 BC |

|---|---|

| Country | Mesopotamia |

| Language | Sumerian |

| Media type | Clay tablet |

The Epic of Gilgamesh (/ˈɡɪlɡəmɛʃ/) is an epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia that is often regarded as the earliest surviving great work of literature and the second oldest religious text, after the Pyramid Texts. The literary history of Gilgamesh begins with five Sumerian poems about Bilgamesh (Sumerian for "Gilgamesh"), king of Uruk, dating from the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2100 BC). These independent stories were later used as source material for a combined epic in Akkadian. The first surviving version of this combined epic, known as the "Old Babylonian" version dates to the 18th century BC and is titled after its incipit, Shūtur eli sharrī ("Surpassing All Other Kings"). Only a few tablets of it have survived. The later "standard" version compiled by Sîn-lēqi-unninni dates from the 13th to the 10th centuries BC and bears the incipit Sha naqba īmuru ("He who Saw the Abyss", in modern terms: "He who Sees the Unknown").

Approximately two thirds of this longer, twelve-tablet version have been recovered. Some of the best copies were discovered in the library ruins of the 7th-century BC Assyrian king Ashurbanipal.

The first half of the story discusses Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, and Enkidu, a wild man created by the gods to stop Gilgamesh from oppressing the people of Uruk. After Enkidu becomes civilized through sexual initiation with a prostitute, he travels to Uruk, where he challenges Gilgamesh to a test of strength. Gilgamesh wins the contest; nonetheless, the two become friends. Together, they make a six-day journey to the legendary Cedar Forest, where they plan to slay the Guardian, Humbaba the Terrible, and cut down the sacred Cedar. The goddess Ishtar sends the Bull of Heaven to punish Gilgamesh for spurning her advances. Gilgamesh and Enkidu kill the Bull of Heaven after which the gods decide to sentence Enkidu to death and kill him.

In the second half of the epic, distress over Enkidu's death causes Gilgamesh to undertake a long and perilous journey to discover the secret of eternal life. He eventually learns that "Life, which you look for, you will never find. For when the gods created man, they let death be his share, and life withheld in their own hands". However, because of his great building projects, his account of Siduri's advice, and what the immortal man Utnapishtim told him about the Great Flood, Gilgamesh's fame survived well after his death with expanding interest in the Gilgamesh story which has been translated into many languages and is featured in works of popular fiction.

History

Ancient Assyrian statue currently in the Louvre, possibly representing Gilgamesh

Distinct sources exist from over a 2000-year timeframe. The earliest Sumerian poems are now generally considered to be distinct stories, rather than parts of a single epic. They date from as early as the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2100 BC). The Old Babylonian tablets (c. 1800 BC), are the earliest surviving tablets for a single Epic of Gilgamesh narrative. The older Old Babylonian tablets and later Akkadian version are important sources for modern translations, with the earlier texts mainly used to fill in gaps (lacunae)

in the later texts. Although several revised versions based on new

discoveries have been published, the epic remains incomplete. Analysis of the Old Babylonian text has been used to reconstruct possible earlier forms of the Epic of Gilgamesh. The most recent Akkadian version (c. 1200 BC), also referred to as the standard version, consisting of twelve tablets, was edited by Sin-liqe-unninni and was found in the Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh.

...this discovery is evidently destined to excite a lively controversy. For the present the orthodox people are in great delight, and are very much prepossessed by the corroboration which it affords to Biblical history. It is possible, however, as has been pointed out, that the Chaldean inscription, if genuine, may be regarded as a confirmation of the statement that there are various traditions of the deluge apart from the Biblical one, which is perhaps legendary like the restThe New York Times, front page, 1872

The Epic of Gilgamesh was discovered by Austen Henry Layard, Hormuzd Rassam, and W. K. Loftus in 1853. The central character of Gilgamesh was initially reintroduced to the world as "Izdubar", before the cuneiform logographs in his name could be pronounced accurately. The first modern translation was published in the early 1870s by George Smith.

Smith then made further discoveries of texts on his later expeditions,

which culminated in his final translation which is given in his book The Chaldaean Account of Genesis (1880).

The most definitive modern translation is a two-volume critical work by Andrew George, published by Oxford University Press

in 2003. A book review by the Cambridge scholar, Eleanor Robson, claims

that George's is the most significant critical work on Gilgamesh in the

last 70 years. George discusses the state of the surviving material, and provides a tablet-by-tablet exegesis,

with a dual language side-by-side translation. In 2004, Stephen

Mitchell supplied a controversial version that takes many liberties with

the text and includes modernized allusions and commentary relating to

the Iraq War of 2003.

The first direct Arabic translation from the original tablets was made in the 1960s by the Iraqi archaeologist Taha Baqir.

The discovery of artifacts (c. 2600 BC) associated with Enmebaragesi of Kish,

mentioned in the legends as the father of one of Gilgamesh's

adversaries, has lent credibility to the historical existence of

Gilgamesh.

In 1998, American historian Theodore Kwasman discovered a piece

believed to have contained the first lines of the epic in the storeroom

of the British Museum,

the fragment, found in 1878 and dated to between 600BC and 100BC, had

remained unexamined by experts for more than a century since its

recovery.

The fragment read "He who saw all, who was the foundation of the land,

who knew (everything), was wise in all matters: Gilgamesh."

Versions

From

the diverse sources found, two main versions of the epic have been

partially reconstructed: the standard Akkadian version, or He who saw the deep, and the Old Babylonian version, or Surpassing all other kings. Five earlier Sumerian

poems about Gilgamesh have been partially recovered, some with

primitive versions of specific episodes in the Akkadian version, others

with unrelated stories.

Standard Akkadian version

The standard version was discovered by Hormuzd Rassam in the library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh in 1853. It was written in a dialect of Akkadian that was used for literary purposes. This version was compiled by Sin-liqe-unninni sometime between 1300 and 1000 BC from earlier texts.

The standard Akkadian version has different opening words, or incipit,

from the older version. The older version begins with the words

"Surpassing all other kings", while the standard version has "He who saw

the deep" (ša nagba īmuru), "deep" referring to the mysteries of the information brought back by Gilgamesh from his meeting with Uta-Napishti (Utnapishtim) about Ea, the fountain of wisdom.

Gilgamesh was given knowledge of how to worship the gods, why death was

ordained for human beings, what makes a good king, and how to live a

good life. The story of Utnapishtim, the hero of the flood myth, can also be found in the Babylonian Epic of Atrahasis.

The 12th tablet is a sequel to the original 11, and was probably

added at a later date. It bears little relation to the well-crafted

11-tablet epic; the lines at the beginning of the first tablet are

quoted at the end of the 11th tablet, giving it circularity and

finality. Tablet 12 is a near copy of an earlier Sumerian tale, a

prequel, in which Gilgamesh sends Enkidu to retrieve some objects of his

from the Underworld, and he returns in the form of a spirit to relate

the nature of the Underworld to Gilgamesh.

Content of the standard version tablets

This summary is based on Andrew George's translation.

Tablet one

The story introduces Gilgamesh, king of Uruk.

Gilgamesh, two-thirds god and one-third man, is oppressing his people,

who cry out to the gods for help. For the young women of Uruk this

oppression takes the form of a droit du seigneur,

or "lord's right", to sleep with brides on their wedding night. For the

young men (the tablet is damaged at this point) it is conjectured that

Gilgamesh exhausts them through games, tests of strength, or perhaps

forced labour on building projects. The gods respond to the people's

pleas by creating an equal to Gilgamesh who will be able to stop his

oppression. This is the primitive man, Enkidu,

who is covered in hair and lives in the wild with the animals. He is

spotted by a trapper, whose livelihood is being ruined because Enkidu is

uprooting his traps. The trapper tells the sun-god Shamash about the man, and it is arranged for Enkidu to be seduced by Shamhat, a temple prostitute, his first step towards being tamed. After six days and seven nights (or two weeks, according to more recent scholarship)

of lovemaking and teaching Enkidu about the ways of civilization, she

takes Enkidu to a shepherd's camp to learn how to be civilized.

Gilgamesh, meanwhile, has been having dreams about the imminent arrival

of a beloved new companion and asks his mother, Ninsun, to help interpret these dreams.

Tablet two

Shamhat

brings Enkidu to the shepherds' camp, where he is introduced to a human

diet and becomes the night watchman. Learning from a passing stranger

about Gilgamesh's treatment of new brides, Enkidu is incensed and

travels to Uruk to intervene at a wedding. When Gilgamesh attempts to

visit the wedding chamber, Enkidu blocks his way, and they fight. After a

fierce battle, Enkidu acknowledges Gilgamesh's superior strength and

they become friends. Gilgamesh proposes a journey to the Cedar Forest to

slay the monstrous demi-god Humbaba in order to gain fame and renown. Despite warnings from Enkidu and the council of elders, Gilgamesh is not deterred.

Tablet three

The elders give Gilgamesh advice for his journey. Gilgamesh visits his mother, the goddess Ninsun, who seeks the support and protection of the sun-god Shamash

for their adventure. Ninsun adopts Enkidu as her son, and Gilgamesh

leaves instructions for the governance of Uruk in his absence.

Tablet four

Gilgamesh and Enkidu journey to the Cedar Forest.

Every few days they camp on a mountain, and perform a dream ritual.

Gilgamesh has five terrifying dreams about falling mountains,

thunderstorms, wild bulls, and a thunderbird that breathes fire. Despite

similarities between his dream figures and earlier descriptions of

Humbaba, Enkidu interprets these dreams as good omens, and denies that

the frightening images represent the forest guardian. As they approach

the cedar mountain, they hear Humbaba bellowing, and have to encourage

each other not to be afraid.

Tablet five

Tablet V of the Epic of Gilgamesh

div>

div>

Reverse side of the newly discovered tablet V of the Epic of Gilgamesh. It dates back to the old Babylonian period, 2003–1595 BC and is currently housed in the Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraq

The heroes enter the cedar forest. Humbaba,

the guardian of the Cedar Forest, insults and threatens them. He

accuses Enkidu of betrayal, and vows to disembowel Gilgamesh and feed

his flesh to the birds. Gilgamesh is afraid, but with some encouraging

words from Enkidu the battle commences. The mountains quake with the

tumult and the sky turns black. The god Shamash

sends 13 winds to bind Humbaba, and he is captured. Humbaba pleads for

his life, and Gilgamesh pities him. He offers to make Gilgamesh king of

the forest, to cut the trees for him, and to be his slave. Enkidu,

however, argues that Gilgamesh should kill Humbaba to establish his

reputation forever. Humbaba curses them both and Gilgamesh dispatches

him with a blow to the neck, as well as killing his seven sons.

The two heroes cut down many cedars, including a gigantic tree that

Enkidu plans to fashion into a gate for the temple of Enlil. They build a

raft and return home along the Euphrates with the giant tree and (possibly) the head of Humbaba.

Tablet six

Gilgamesh rejects the advances of the goddess Ishtar because of her mistreatment of previous lovers like Dumuzi. Ishtar asks her father Anu to send Gugalanna, the Bull of Heaven, to avenge her. When Anu rejects her complaints, Ishtar threatens to raise the dead

who will "outnumber the living" and "devour them". Anu becomes

frightened, and gives in to her. Ishtar leads Gugalanna to Uruk, and it

causes widespread devastation. It lowers the level of the Euphrates

river, and dries up the marshes. It opens up huge pits that swallow 300

men. Without any divine assistance, Enkidu and Gilgamesh attack and slay

it, and offer up its heart to Shamash. When Ishtar cries out, Enkidu

hurls one of the hindquarters of the bull at her. The city of Uruk

celebrates, but Enkidu has an ominous dream about his future failure.

Tablet seven

In

Enkidu's dream, the gods decide that one of the heroes must die because

they killed Humbaba and Gugalanna. Despite the protestations of

Shamash, Enkidu is marked for death. Enkidu curses the great door he has

fashioned for Enlil's temple. He also curses the trapper and Shamhat

for removing him from the wild. Shamash reminds Enkidu of how Shamhat

fed and clothed him, and introduced him to Gilgamesh. Shamash tells him

that Gilgamesh will bestow great honors upon him at his funeral, and

will wander into the wild consumed with grief. Enkidu regrets his curses

and blesses Shamhat instead. In a second dream, however, he sees

himself being taken captive to the Netherworld

by a terrifying Angel of Death. The underworld is a "house of dust" and

darkness whose inhabitants eat clay, and are clothed in bird feathers,

supervised by terrifying beings. For 12 days, Enkidu's condition

worsens. Finally, after a lament that he could not meet a heroic death

in battle, he dies. In a famous line from the epic, Gilgamesh clings to

Enkidu's body and denies that he has died until a maggot drops from the

corpse's nose.

Tablet eight

Gilgamesh

delivers a lament for Enkidu, in which he calls upon mountains,

forests, fields, rivers, wild animals, and all of Uruk to mourn for his

friend. Recalling their adventures together, Gilgamesh tears at his hair

and clothes in grief. He commissions a funerary statue, and provides

grave gifts from his treasury to ensure that Enkidu has a favourable

reception in the realm of the dead. A great banquet is held where the

treasures are offered to the gods of the Netherworld. Just before a

break in the text there is a suggestion that a river is being dammed,

indicating a burial in a river bed, as in the corresponding Sumerian

poem, The Death of Gilgamesh.

Tablet nine

Tablet

nine opens with Gilgamesh roaming the wild wearing animal skins,

grieving for Enkidu. Having now become fearful of his own death, he

decides to seek Utnapishtim ("the Faraway"), and learn the secret of eternal life. Among the few survivors of the Great Flood,

Utnapishtim and his wife are the only humans to have been granted

immortality by the gods. Gilgamesh crosses a mountain pass at night and

encounters a pride of lions. Before sleeping he prays for protection to

the moon god Sin. Then, waking from an encouraging dream, he kills the

lions and uses their skins for clothing. After a long and perilous

journey, Gilgamesh arrives at the twin peaks of Mount Mashu at the end of the earth. He comes across a tunnel, which no man has ever entered, guarded by two scorpion monsters,

who appear to be a married couple. The husband tries to dissuade

Gilgamesh from passing, but the wife intervenes, expresses sympathy for

Gilgamesh, and (according to the poem's editor Benjamin Foster) allows

his passage. He passes under the mountains along the Road of the Sun. In

complete darkness he follows the road for 12 "double hours", managing

to complete the trip before the Sun catches up with him. He arrives at

the Garden of the gods, a paradise full of jewel-laden trees.

Tablet ten

Gilgamesh meets alewife Siduri,

who assumes that he is a murderer or thief because of his disheveled

appearance. Gilgamesh tells her about the purpose of his journey. She

attempts to dissuade him from his quest, but sends him to Urshanabi

the ferryman, who will help him cross the sea to Utnapishtim.

Gilgamesh, out of spontaneous rage, destroys the stone charms that

Urshanabi keeps with him. He tells him his story, but when he asks for

his help, Urshanabi informs him that he has just destroyed the objects

that can help them cross the Waters of Death, which are deadly to the

touch. Urshanabi instructs Gilgamesh to cut down 120 trees and fashion

them into punting poles. When they reach the island where Utnapishtim

lives, Gilgamesh recounts his story, asking him for his help.

Utnapishtim reprimands him, declaring that fighting the common fate of

humans is futile and diminishes life's joys.

Tablet eleven

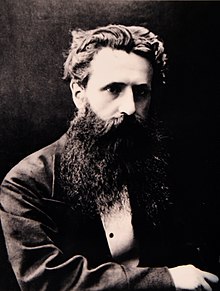

George Smith, the man who transliterated and read the so-called "Babylonian Flood Story" of Tablet XI

The main point seems to be that when Enlil granted eternal life

it was a unique gift. As if to demonstrate this point, Utnapishtim

challenges Gilgamesh to stay awake for six days and seven nights.

Gilgamesh falls asleep, and Utnapishtim instructs his wife to bake a

loaf of bread on each of the days he is asleep, so that he cannot deny

his failure to keep awake. Gilgamesh, who is seeking to overcome death,

cannot even conquer sleep. After instructing Urshanabi the ferryman to

wash Gilgamesh, and clothe him in royal robes, they depart for Uruk.

As they are leaving, Utnapishtim's wife asks her husband to offer

a parting gift. Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh that at the bottom of the

sea there lives a boxthorn-like

plant that will make him young again. Gilgamesh, by binding stones to

his feet so he can walk on the bottom, manages to obtain the plant.

Gilgamesh proposes to investigate if the plant has the hypothesized

rejuvenation ability by testing it on an old man once he returns to

Uruk.

There is a plant that looks like a box-thorn, it has prickles like a dogrose, and will prick one who plucks it. But if you can possess this plant, you'll be again as you were in your youth

This plant, Ur-shanabi, is the "Plant of Heartbeat", with it a man can regain his vigour. To Uruk-the-sheepfold I will take it, to an ancient I will feed some and put the plant to the test!

Unfortunately, when Gilgamesh stops to bathe, it is stolen by a serpent,

who sheds its skin as it departs. Gilgamesh weeps at the futility of

his efforts, because he has now lost all chance of immortality. He

returns to Uruk, where the sight of its massive walls prompts him to

praise this enduring work to Urshanabi.

Tablet twelve

This tablet is mainly an Akkadian translation of an earlier Sumerian poem, "Gilgamesh and the Netherworld" (also known as "Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld" and variants), although it has been suggested that it is derived from an unknown version of that story.

The contents of this last tablet are inconsistent with previous ones:

Enkidu is still alive, despite having died earlier in the epic. Because

of this, its lack of integration with the other tablets, and the fact

that it is almost a copy of an earlier version, it has been referred to

as an 'inorganic appendage' to the epic.

Alternatively, it has been suggested that "its purpose, though crudely

handled, is to explain to Gilgamesh (and the reader) the various fates

of the dead in the Afterlife" and in "an awkward attempt to bring

closure", it both connects the Gilgamesh of the epic with the Gilgamesh who is the King of the Netherworld,

and is "a dramatic capstone whereby the twelve-tablet epic ends on one

and the same theme, that of "seeing" (= understanding, discovery, etc.),

with which it began."

Gilgamesh complains to Enkidu that various of his possessions

(the tablet is unclear exactly what — different translations include a

drum and a ball) have fallen into the underworld. Enkidu offers to bring

them back. Delighted, Gilgamesh tells Enkidu what he must and must not

do in the underworld if he is to return. Enkidu does everything which he

was told not to do. The underworld keeps him. Gilgamesh prays to the

gods to give him back his friend. Enlil and Suen don't reply, but Ea and Shamash

decide to help. Shamash makes a crack in the earth, and Enkidu's ghost

jumps out of it. The tablet ends with Gilgamesh questioning Enkidu about

what he has seen in the underworld.

Old Babylonian versions

This version of the epic, called in some fragments Surpassing all other kings, is composed of tablets and fragments from diverse origins and states of conservation. It remains incomplete in its majority, with several tablets missing and big lacunae in those found. They are named after their current location or the place where they were found.

Pennsylvania tablet

Surpassing all other kings

Tablet II, greatly correlates with tablets I-II of the standard

version.

Gilgamesh tells his mother Ninsun about two dreams he had. His mother

explains that they mean that a new companion will soon arrive at Uruk.

In the meanwhile the wild Enkidu and the priestess (here called

Shamkatum) are making love. She tames him in company of the shepherds by

offering him bread and beer. Enkidu helps the shepherds by guarding the

sheep. They travel to Uruk to confront Gilgamesh and stop his abuses.

Enkidu and Gilgamesh battle but Gilgamesh breaks off the fight. Enkidu

praises Gilgamesh.

Yale tablet

Surpassing all other kings

Tablet III, partially matches tablets II-III of the standard version.

For reasons unknown (the tablet is partially broken) Enkidu is in a sad

mood. In order to cheer him up Gilgamesh suggests going to the Pine

Forest to cut down trees and kill Humbaba (known here as Huwawa). Enkidu

protests, as he knows Huwawa and is aware of his power. Gilgamesh talks

Enkidu into it with some words of encouragement, but Enkidu remains

reluctant. They prepare, and call for the elders. The elders also

protest, but after Gilgamesh talks to them, they agree to let him go.

After Gilgamesh asks his god (Shamash) for protection, and both he and

Enkidu equip themselves, they leave with the elder's blessing and

counsel.

Philadelphia fragment

Possibly another version of the contents of the Yale Tablet, practically irrecoverable.

Nippur school tablet

In the journey to the cedar forest and Huwawa, Enkidu interprets one of Gilgamesh's dreams.

Tell Harmal tablets

Fragments

from two different versions/tablets tell how Enkidu interprets one of

Gilgamesh's dreams on the way to the Forest of Cedar, and their

conversation when entering the forest.

Ishchali tablet

After

defeating Huwawa, Gilgamesh refrains from slaying him, and urges Enkidu

to hunt Huwawa's "seven auras". Enkidu convinces him to smite their

enemy. After killing Huwawa and the auras, they chop down part of the

forest and discover the gods' secret abode. The rest of the tablet is

broken.

The auras are not referred to in the standard version, but are in one of the Sumerian poems.

Partial fragment in Baghdad

Partially overlapping the felling of the trees from the Ishchali tablet.

Sippar tablet

Partially

overlapping the standard version tablets IX–X.

Gilgamesh mourns the death of Enkidu wandering in his quest for

immortality. Gilgamesh argues with Shamash about the futility of his

quest. After a lacuna, Gilgamesh talks to Siduri

about his quest and his journey to meet Utnapishtim (here called

Uta-na'ishtim). Siduri attempts to dissuade Gilgamesh in his quest for

immortality, urging him to be content with the simple pleasures of life.

After one more lacuna, Gilgamesh smashes the "stone ones" and talks to

the ferryman Urshanabi (here called Sur-sunabu). After a short

discussion, Sur-sunabu asks him to carve 300 oars so that they may cross

the waters of death without needing the "stone ones". The rest of the

tablet is missing.

The text on the Old Babylonian Meissner fragment (the larger

surviving fragment of the Sippar tablet) has been used to reconstruct

possible earlier forms of the Epic of Gilgamesh, and it has been

suggested that a "prior form of the story – earlier even than that

preserved on the Old Babylonian fragment – may well have ended with

Siduri sending Gilgamesh back to Uruk..." and "Utnapistim was not

originally part of the tale."

Sumerian poems

There are five extant Gilgamesh stories in the form of older poems in Sumerian.

These probably circulated independently, rather than being in the form

of a unified epic. Some of the names of the main characters in these

poems differ slightly from later Akkadian names; for example,

"Bilgamesh" is written instead of "Gilgamesh", and there are some

differences in the underlying stories such as the fact that Enkidu is

Gilgamesh's servant in the Sumerian version:

- The lord to the Living One's Mountain and Ho, hurrah! correspond to the Cedar Forest episode (standard version tablets II–V). Gilgamesh and Enkidu travel with other men to the Forest of Cedar. There, trapped by Huwawa, Gilgamesh tricks him (with Enkidu's assistance in one of the versions) into giving up his auras, thus losing his power.

- Hero in battle corresponds to the Bull of Heaven episode (standard version tablet VI) in the Akkadian version. The Bull's voracious appetite causes drought and hardship in the land while Gilgamesh feasts. Lugalbanda convinces him to face the beast and fights it alongside Enkidu.

- The envoys of Akka has no corresponding episode in the epic, but the themes of whether to show mercy to captives, and counsel from the city elders, also occur in the standard version of the Humbaba story. In the poem, Uruk faces a siege from a Kish army led by King Akka, whom Gilgamesh defeats and forgives.

- In those days, in those far-off days, otherwise known as Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld, is the source for the Akkadian translation included as tablet XII in the standard version, telling of Enkidu's journey to the Netherworld. It is also the main source of information for the Sumerian creation myth and the story of "Inanna and the Huluppu Tree".[25]

- The great wild bull is lying down, a poem about Gilgamesh's

death, burial and consecration as a semigod, reigning and giving

judgement over the dead. After dreaming of how the gods decide his fate

after death, Gilgamesh takes counsel, prepares his funeral and offers

gifts to the gods. Once deceased, he is buried under the Euphrates,

taken off its course and later returned to it.

Later influence

Relationship to the Bible

Various themes, plot elements, and characters in the Epic of Gilgamesh have counterparts in the Hebrew Bible—notably, the accounts of the Garden of Eden, the advice from Ecclesiastes, and the Genesis flood narrative.

Garden of Eden

The parallels between the stories of Enkidu/Shamhat and Adam/Eve have been long recognized by scholars.

In both, a man is created from the soil by a god, and lives in a

natural setting amongst the animals. He is introduced to a woman who

tempts him. In both stories the man accepts food from the woman, covers

his nakedness, and must leave his former realm, unable to return. The

presence of a snake that steals a plant of immortality from the hero

later in the epic is another point of similarity.

Advice from Ecclesiastes

A rare proverb about the strength of a triple-stranded rope, "a

triple-stranded rope is not easily broken", is common to both books.

Noah's flood

Andrew George submits that the Genesis flood narrative matches that in Gilgamesh so closely that "few doubt" that it derives from a Mesopotamian account. What is particularly noticeable is the way the Genesis flood story follows the Gilgamesh flood tale "point by point and in the same order", even when the story permits other alternatives. In a 2001 Torah commentary released on behalf of the Conservative Movement of Judaism, rabbinic scholar Robert Wexler

stated: "The most likely assumption we can make is that both Genesis

and Gilgamesh drew their material from a common tradition about the

flood that existed in Mesopotamia. These stories then diverged in the

retelling." Ziusudra, Utnapishtim and Noah are the respective heroes of the Sumerian, Akkadian and biblical flood legends of the ancient Near East.

Additional biblical parallels

Matthias Henze suggests that Nebuchadnezzar's madness in the biblical Book of Daniel draws on the Epic of Gilgamesh.

He claims that the author uses elements from the description of Enkidu

to paint a sarcastic and mocking portrait of the king of Babylon.

Many characters in the Epic have mythical biblical parallels, most notably Ninti, the Sumerian goddess of life, was created from Enki's rib to heal him after he had eaten forbidden flowers. It is suggested that this story served as the basis for the story of Eve created from Adam's rib in the Book of Genesis.

Esther J. Hamori, in Echoes of Gilgamesh in the Jacob Story, also claims that the myth of Jacob and Esau is paralleled with the wrestling match between Gilgamesh and Enkidu.

Book of Giants

Gilgamesh is mentioned in one version of The Book of Giants which is related to the Book of Enoch

presumably written by biblical grandfather of Noah. The Book of Giants

version found at Qumran mentions the Sumerian hero Gilgamesh and the

monster Humbaba with the Watchers and giants.

Influence on Homer

Numerous scholars have drawn attention to various themes, episodes, and verses, indicating that the Epic of Gilgamesh had a substantial influence on both of the epic poems ascribed to Homer. These influences are detailed by Martin Litchfield West in The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth. According to Tzvi Abusch of Brandeis University, the poem "combines the power and tragedy of the Iliad with the wanderings and marvels of the Odyssey. It is a work of adventure, but is no less a meditation on some fundamental issues of human existence."

In popular culture

The Epic of Gilgamesh has inspired many works of literature, art, and music, as Theodore Ziolkowski points out in his book Gilgamesh Among Us: Modern Encounters With the Ancient Epic (2011). It was only after World War I that the Gilgamesh epic reached a modern audience, and only after World War II that it was featured in a variety of genres.