A wildlife crossing structure on the Trans-Canada Highway in Banff National Park,

Canada. Wildlife-friendly overpasses and underpasses have helped

restore connectivity in the landscape for wolves, bears, elk, and other

species.

Rewilding is large-scale conservation aimed at restoring and

protecting natural processes and core wilderness areas, providing

connectivity between such areas, and protecting or reintroducing apex predators and keystone species.

Rewilding projects may require ecological restoration or wilderness

engineering, particularly to restore connectivity between fragmented

protected areas, and reintroduction of predators and keystone species

where extirpated. The ultimate goal of rewilding efforts is to create

ecosystems requiring passive management by limiting human control of

ecosystems. Successful long term rewilding projects should be considered

to have little to no human-based ecological management, as successful

reintroduction of keystone species creates a self-regulatory and self-sustaining stable ecosystem, with near pre-human levels of biodiversity.

Origin

The word rewilding was coined by conservationist and activist Dave Foreman, one of the founders of the group Earth First! who went on to help establish both the Wildlands Project (now the Wildlands Network) and the Rewilding Institute. The term first occurred in print in 1990 and was refined by conservation biologists Michael Soulé and Reed Noss in a paper published in 1998. According to Soulé and Noss, rewilding is a conservation method based on "cores, corridors, and carnivores." The concepts of cores, corridors, and carnivores were developed further in 1999. Dave Foreman subsequently wrote the first full-length exegesis of rewilding as a conservation strategy.

More recently, anthropologist Layla AbdelRahim

offered a new definition of rewilding: "Wilderness is ... a cumulative

topos of diversity, movement, and chaos, while wildness is a

characteristic that refers to socio-environmental relationships".

According to her, because civilization is a constantly growing

enterprise, it has completely colonized the earth and imperiled life on

the planet. Therefore, rewilding can start only with a revolution in the

anthropology that constructs the human as predator.

History

Rewilding was developed as a method to preserve functional ecosystems and reduce biodiversity loss, incorporating research in island biogeography and the ecological role of large carnivores. In 1967, The Theory of Island Biogeography by Robert H. MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson

established the importance of considering the size and isolation of

wildlife conservation areas, stating that protected areas remained

vulnerable to extinctions if small and isolated. In 1987, William D. Newmark's study of extinctions in national parks in North America added weight to the theory. The publications intensified debates on conservation approaches. With the creation of the Society for Conservation Biology in 1985, conservationists began to focus on reducing habitat loss and fragmentation.

Elements required for successful rewilding

Rewilding

is important on land but perhaps more important is where land meets the

water. Dam removal is the first of many steps in the process of

rewilding in the riverine ecosystems. However, there are problems that

should be addressed before, during, and after the dam removal. The

problems are the sediments that have built up and wash out filling in

spawning beds should be controlled and directed, then eliminating any

and all clear cutting of trees near river banks as it raises the

temperature of the water, and stopping industrial discharges for obvious

reasons.

At 90 different dam sites it has been confirmed that after a dam is

built the ecosystem does rebound. However, the trend will eventually

slow, stop and in some cases decline. This is often due to anthropogenic

chemical, light, and noise pollution as the large bodies of water draw

human activity and recreation. Nemecek writes that, "researchers found

that the number of species within any given area dropped by 50%.

Lastly, food sources for native animals and fish need to be introduced

so as to improve the long-term sustainability of native species and

curtail and/or eliminate the introduction of invasive species.

Key species

The

beaver is by far the most important element of a riverine ecosystem.

Firstly, the dams they build create micro ecosystems that can be used as

spawning beds for salmon and collect invertebrates for the salmon fry

to feed on. The dams, again built by beavers, create wetlands for plant,

insect, and bird life. Specific trees, alder, birch, cottonwood, and

willow are important to beaver's diets and must be encouraged to grow in

areas accessible by the animals. In terms of seeding the birds can do

much of the rest. These animals have a trickle down effect as they create ecosystems that have the potential to grow exponentially.

Major rewilding projects

Between 800 and 1150 wild koniks live in the Oostvaardersplassen, a 56 km² rewilding project in the Netherlands

Both grassroots groups and major international conservation organizations have incorporated rewilding into projects to protect and restore large-scale core wilderness areas, corridors

(or connectivity) between them, and apex predators, carnivores, or

keystone species (species which interact strongly with the environment,

such as elephant and beaver). Projects include the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative in North America (also known as Y2Y) and the European Green Belt, built along the former Iron Curtain; transboundary projects, including those in southern Africa funded by the Peace Parks Foundation;

community-conservation projects, such as the wildlife conservancies of

Namibia and Kenya; and projects organized around ecological restoration,

including Gondwana Link, regrowing native bush in a hotspot of endemism in southwest Australia, and the Area de Conservacion Guanacaste, restoring dry tropical forest and rainforest in Costa Rica. European Wildlife, established in 2008, advocates the establishment of a European Centre of Biodiversity at the German–Austrian–Czech borders.

In North America, another major project aims to restore the prairie grasslands of the Great Plains. The American Prairie Foundation is reintroducing bison on private land in the Missouri Breaks region of north-central Montana, with the goal of creating a prairie preserve larger than Yellowstone National Park.

Dam removal has led to the restoration of many river systems in the

Pacific Northwest. This has been done in an effort to restore salmon

populations specifically but with other species in mind. "These dam

removals provide perhaps the best example of large-scale environmental

remediation in the twenty-first century. This restoration, however, has

occurred on a case-by-case basis, without a comprehensive plan. The

result has been to put into motion ongoing rehabilitation efforts in

four distinct river basins: the Elwha and White Salmon in Washington and

the Sandy and Rogue in Oregon."

An organization called Rewilding Australia

has formed which intends to restore various marsupials and other

Australian animals which have been extirpated from the mainland, such as

Eastern quolls and Tasmanian devils.

Projects in Europe

European bison (Bison bonasus);

Europe's largest living land animal. The European bison was driven to

extinction in the wild in 1927; in the mid-20th century and early 21st

century, the bison has been re-introduced into the wild. The bison

stands nearly 2 metres tall and weighs as much as 1,000 kg.

In the 1980s, the Dutch government began introducing proxy species in the Oostvaardersplassen nature reserve in order to recreate a grassland ecology.

Though not explicitly referred to as rewilding, nevertheless many of

the goals and intentions of the project were in line with those of

rewilding. The reserve is considered somewhat controversial due to the

lack of predators and other native megafauna such as wolves, bears, lynx, elk, boar, and wisent.

Since the 1980's, 8.5 million trees have been planted in the United Kingdom in an area of the midlands around the villages of Moira and Donisthorpe, close to Leicester. The area is called The National Forest. Another, larger, reforestation project, aiming to plant 50 million trees is beginning in South Yorkshire, called The Northern Forest. Despite this, the UK government has been criticised for not achieving its tree planting goals. The Knepp Estate and Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation have overseen reintroductions of extinct bird species in the UK.

In 2011, the 'Rewilding Europe' initiative was established with the aim of rewilding 1 million hectares of land in ten areas including the western Iberian Peninsula, Velebit, the Carpathians and the Danube delta by 2020, mostly abandoned farmland among other identified candidate site. The present project considers only species that are still present in Europe, such as the Iberian lynx, Eurasian lynx, wolf, European jackal, Brown bear, chamois, Spanish ibex, European bison, red deer, griffon vulture, cinereous vulture, Egyptian vulture, Great white pelican and horned viper, along with a few primitive breeds of domestic horse and cattle as proxies for the extinct tarpan and aurochs. Since 2012, Rewilding Europe is heavily involved in the Tauros Programme, which seeks to recreate the phenotype of the aurochs, the wild ancestors of domestic cattle by selectively breeding existing breeds of cattle. Many projects also employ domestic water buffalo as a grazing proxy for the extinct European water buffalo.Reviving Europe.

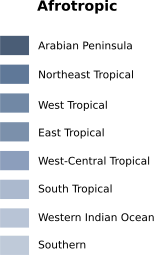

Historic range of the European bison.

Maximum Holocene range

Range during the high middle ages

Relict 20th century populations

In 2010 and 2011, an unrelated initiative in the village of San Cebrián de Mudá (190 inhabitants) in Palencia, northern Spain released 18 European bisons (a species extinct in Spain since the Middle Ages) in a natural area already inhabited by roe deer, wild boar, red fox and grey wolf, as part of the creation of a 240-hectare "Quaternary Park". Three Przewalski horses from a breeding center in Le Villaret, France were added to the park in October 2012. Onagers and "aurochs" were planned to follow.

On 11 April 2013, eight European bison (one male, five females

and two calves) were released into the wild in the Bad Berleburg region

of Germany, after 300 years of absence from the region.

In 2014 the German government built a 3 km road tunnel to remove an Autobahn from the Leutratal und Cospoth nature reserve.

In 2016 and 2018, the True Nature Foundation reintroduced in

total 7 European bison of the Lowland-Caucasian breeding line in Anciles

Wildlife Reserve in the Parque Regional de Picos de Europa in the Cantabrian mountains in northern Spain.

Pleistocene rewilding

Pleistocene rewilding was proposed by the Brazilian ecologist Mauro Galetti in 2004.

He suggested the introduction of elephants (and other proxies of

extinct megafauna) from circuses and zoos to private lands in the

Brazilian cerrado. In 2005, stating that much of the original megafauna

of North America—including mammoths, ground sloths, and sabre-toothed

cats—became extinct after the arrival of humans, Paul S. Martin

proposed restoring the ecological balance by replacing them with

species which have similar ecological roles, such as Asian or African

elephants.

A reserve now exists for formerly captive elephants on the Brazilian Cerrado.

A controversial 2005 editorial in Nature,

signed by a number of conservation biologists, took up the argument,

urging that elephants, lions, and cheetahs could be reintroduced in

protected areas in the Great Plains. The Bolson tortoise,

discovered in 1959 in Durango, Mexico, was the first species proposed

for this restoration effort, and in 2006 the species was reintroduced to

two ranches in New Mexico owned by media mogul Ted Turner. Other proposed species include various camelids, equids, and peccaries.

In 1988, researcher Sergey A. Zimov established the Pleistocene Park

in northeastern Siberia to test the possibility of restoring a full

range of grazers and predators, with the aim of recreating an ecosystem

similar to the one in which mammoths lived.

Yakutian horses, reindeer, snow sheep, elk, yak and moose were

reintroduced, and reintroduction is also planned for bactrian camels,

red deer, and Siberian tigers. The wood bison, a close relative of the

ancient bison that died out in Siberia 1000 or 2000 years ago, is also

an important species for the ecology of Siberia. In 2006, 30 bison

calves were flown from Edmonton, Alberta to Yakutsk and placed in the

government-run reserve of Ust'-Buotama. This project remains

controversial — a letter published in Conservation Biology

accused the Pleistocene camp of promoting "Frankenstein ecosystems,"

stating that "the biggest problem is not the possibility of failing to

restore lost interactions, but rather the risk of getting new, unwanted

interactions instead."

The authors proposed that—rather than trying to restore a lost

megafauna—conservationists should dedicate themselves to restoring

existing species to their original habitats.