| Fusiform face area | |

|---|---|

Human brain, bottom view. Fusiform face area shown in bright blue.

| |

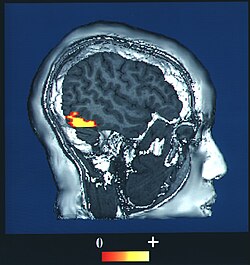

Computer-enhanced fMRI

scan of a person who has been asked to look at faces. The image shows

increased blood flow in cerebral cortex that recognizes faces (FFA).

|

The fusiform face area - FFA (meaning: spindular/spindle-shaped face area) is a part of the human visual system that is specialized for facial recognition. It is located in the Inferior temporal cortex (IT), in the fusiform gyrus (Brodmann area 37).

Structure

The FFA is located in the ventral stream on the ventral surface of the temporal lobe on the lateral side of the fusiform gyrus. It is lateral to the parahippocampal place area. It displays some lateralization, usually being larger in the right hemisphere.

The FFA was discovered and continues to be investigated in humans using positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging

(fMRI) studies. Usually, a participant views images of faces, objects,

places, bodies, scrambled faces, scrambled objects, scrambled places,

and scrambled bodies. This is called a functional localizer.

Comparing the neural response between faces and scrambled faces will

reveal areas that are face-responsive, while comparing cortical

activation between faces and objects will reveal areas that are

face-selective.

Function

The human FFA was first described by Justine Sergent in 1992 and later named by Nancy Kanwisher in 1997 who proposed that the existence of the FFA is evidence for domain specificity

in the visual system. Studies have recently shown that the FFA is

composed of functional clusters that are at a finer spatial scale than

prior investigations have measured.

Electrical stimulation of these functional clusters selectively

distorts face perception, which is causal support for the role of these

functional clusters in perceiving the facial image.

While it is generally agreed that the FFA responds more to faces than

to most other categories, there is debate about whether the FFA is

uniquely dedicated to face processing, as proposed by Nancy Kanwisher

and others, or whether it participates in the processing of other

objects. The expertise hypothesis, as championed by Isabel Gauthier

and others, offers an explanation for how the FFA becomes selective for

faces in most people. The expertise hypothesis suggests that the FFA is

a critical part of a network that is important for individuating

objects that are visually similar because they share a common

configuration of parts. Gauthier et al., in an adversarial collaboration

with Kanwisher,

tested both car and bird experts, and found some activation in the FFA

when car experts were identifying cars and when bird experts were

identifying birds. This finding has been replicated, and expertise effects in the FFA have been found for other categories such as chess displays and x-rays.

Recently, it was found that the thickness of the cortex in the FFA

predicts the ability to recognize faces as well as vehicles.

A 2009 magnetoencephalography study found that objects incidentally perceived as faces, an example of pareidolia,

evoke an early (165-millisecond) activation in the FFA, at a time and

location similar to that evoked by faces, whereas other common objects

do not evoke such activation. This activation is similar to a face-specific ERP component N170.

The authors suggest that face perception evoked by face-like objects is

a relatively early process, and not a late cognitive reinterpretation

phenomenon.

One case study of agnosia provided evidence that faces are processed in a special way. A patient known as C. K., who suffered brain damage as a result of a car accident, later developed object agnosia.

He experienced great difficulty with basic-level object recognition,

also extending to body parts, but performed very well at recognizing

faces.

A later study showed that C. K. was unable to recognize faces that were

inverted or otherwise distorted, even in cases where they could easily

be identified by normal subjects. This is taken as evidence that the fusiform face area is specialized for processing faces in a normal orientation.

Studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging and electrocorticography have demonstrated that activity in the FFA codes for individual faces and the FFA is tuned for behaviorally relevant facial features. An electrocorticography

study found that the FFA is involved in multiple stages of face

processing, continuously from when people see a face until they respond

to it, demonstrating the dynamic and important role the FFA plays as

part of the face perception network.

Another study found that there is stronger activity in the FFA

when a person sees a familiar face as opposed to an unfamiliar one.

Participants were shown different pictures of faces that either had the

same identity, familiar, or faces with separate identities, or

unfamiliar. It found that participants were more accurate at matching

familiar faces than unfamiliar ones. Using an fMRI, they also found that

the participants that were more accurate in identifying familiar faces

had more activity in their right fusiform face area and participants

that were poor at matching had less activity in their right fusiform

area.

History

Function and controversy

The fusiform face area (FFA) is a part of the brain located in the fusiform gyrus with a debated purpose. Some researchers believe that the FFA is evolutionary purposed for face perception. Others believe that the FFA discriminates between any familiar stimuli.

Psychologists debate whether the FFA is activated by faces for an evolutionary or expertise

reason. The conflicting hypotheses stem from the ambiguity in FFA

activation, as the FFA is activated by both familiar objects and faces. A

study regarding novel objects called greebles determined this phenomenon.

When first exposed to greebles, a person's FFA was activated more

strongly by faces than by greebles. After familiarising themselves with

individual greebles or becoming a greeble expert, a person's FFA was

activated equally by faces and greebles. Likewise, children with autism have been shown to develop object recognition at a similarly impaired pace as face recognition. Studies of late patients of autism have discovered that autistic people have lower neuron densities in the FFA

This raises an interesting question, however: Is the poor face

perception due to a reduced number of cells or is there a reduced number

of cells because autistic people seldom perceive faces? Asked simply: Are faces simply objects with which every person has expertise?

Chinese characters similar to those used in Fu et al., which elicit a response in the FFA

There is evidence supporting the FFA's evolutionary face-perception.

Case studies into other dedicated areas of the brain may suggest that

the FFA is intrinsically designed to recognize faces. Other studies have

recognized areas of the brain essential to recognizing environments and

bodies. Without these dedicated areas, people are incapable of recognizing places and bodies. Similar research regarding prosopagnosia has determined that the FFA is essential to the recognition of unique faces.

However, these patients are capable of recognizing the same people

normally by other means, such as voice. Studies involving language

characters have also been conducted in order to ascertain the role of

the FFA in face recognition. These studies have found that objects, such

as Chinese characters, elicit a high response in different areas of the FFA than those areas that elicit a high response from faces. This data implies that certain areas of the FFA have evolutionary face-perception purposes.

Evidence from infants

The

FFA is underdeveloped in children and does not fully develop until

adolescence. This calls into question the evolutionary purpose of the

FFA, as children show the ability to differentiate faces. Two-year-old

babies have been shown to prefer the face of their mother.

Although the FFA is underdeveloped in two-year-old babies, they have

the ability to recognize their mother. Babies as early as three months

old have shown the ability to distinguish between faces. During this time, babies exhibit the ability to differentiate between genders, showing a clear preference for female faces.

It is theorized that, in terms of evolution, babies focus on women for

food, although the preference could simply reflect a bias for the

caregivers they experience. Infants do not appear to use this area for

the perception of faces. Recent fMRI work has found no face selective

area in the brain of infants 4 to 6 months old.

However, given that the adult human brain has been studied far more

extensively than the infant brain, and that infants are still undergoing

major neurodevelopmental processes, it may simply be that the FFA is

not located in anatomically familiar area. It may also be that

activation for many different percepts and cognitive tasks in infants is

diffuse in terms of neural circuitry, as infants are still undergoing

periods of neurogenesis and neural pruning;

this may make it more difficult to distinguish the signal, or what we

would imagine as visual and complex familiar objects (like faces), from

the noise, including static firing rates of neurons, and activity that

is dedicated to a different task entirely than the activity of face

processing. Infant vision involves only light and dark recognition,

recognizing only major features of the face, activating the amygdala. These findings question the evolutionary purpose of the FFA.

Evidence from emotions

Studies into what else may trigger the FFA validates arguments about its evolutionary purpose. There are countless facial expressions

humans use that disturb the structure of the face. These disruptions

and emotions are first processed in the amygdala and later transmitted

to the FFA for facial recognition. This data is then used by the FFA to

determine more static information about the face.

The fact that the FFA is so far downstream in the processing of emotion

suggests that it has little to do with emotion perception and instead

deals in face perception.

Recent evidence, however, shows that the FFA has other functions

regarding emotion. The FFA is differentially activated by faces

exhibiting different emotions. A study has determined that the FFA is

activated more strongly by fearful faces than neutral faces.

This implies that the FFA has functions in processing emotion despite

its downstream processing and questions its evolutionary purpose to

identify faces.