| Hornet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Oriental hornet, Vespa orientalis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Vespidae |

| Subfamily: | Vespinae |

| Genus: | Vespa Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Type species | |

| Vespa crabro

Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Species | |

|

See text

| |

Hornets (insects in the genus Vespa) are the largest of the eusocial wasps, and are similar in appearance to their close relatives yellowjackets. Some species can reach up to 5.5 cm (2.2 in) in length. They are distinguished from other vespine wasps by the relatively large top margin of the head and by the rounded segment of the abdomen just behind the waist. Worldwide, there are 22 recognized species of Vespa, Most species only occur in the tropics of Asia, though the European hornet (Vespa crabro), is widely distributed throughout Europe, Russia, North America and Northeast Asia. Wasps native to North America in the genus Dolichovespula are commonly referred to as hornets (e.g., baldfaced hornets), but are actually yellowjackets.

Like other social wasps, hornets build communal nests by chewing wood to make a papery pulp. Each nest has one queen, who lays eggs and is attended by workers who, while genetically female, cannot lay fertile eggs. Most species make exposed nests in trees and shrubs, but some (like Vespa orientalis) build their nests underground or in other cavities. In the tropics, these nests may last year-round, but in temperate areas, the nest dies over the winter, with lone queens hibernating in leaf litter or other insulative material until the spring.

Hornets are often considered pests, as they aggressively guard their nesting sites when threatened and their stings can be more dangerous than those of bees.

Life cycle

The structure of an incipient nest

In Vespa crabro,

the nest is founded in spring by a fertilized female known as the

queen. She generally selects sheltered places such as dark, hollow tree

trunks. She first builds a series of cells (up to 50) out of chewed tree

bark. The cells are arranged in horizontal layers named combs, each

cell being vertical and closed at the top. An egg is then laid in each

cell. After 5–8 days, the egg hatches, and in the next two weeks, the

larva undergoes its five stages. During this time, the queen feeds it a

protein-rich diet of insects. Then, the larva spins a silk cap over the

cell's opening and, during the next two weeks, transforms into an adult,

a process called metamorphosis.

The adult then eats its way through the silk cap. This first generation

of workers, invariably females, now gradually undertakes all the tasks

formerly carried out by the queen (foraging, nest building, taking care of the brood, etc.) with the exception of egg-laying, which remains exclusive to the queen.

Life history of Vespa crabro

As the colony size

grows, new combs are added, and an envelope is built around the cell

layers until the nest is entirely covered, with the exception of an

entry hole. To be able to build cells in total darkness, they apparently

use gravity to aid them. At the peak of its population, which occurs in

late summer, the colony can reach a size of 700 workers.

At this time, the queen starts producing the first reproductive individuals. Fertilized eggs develop into females (called "gynes"

by entomologists), and unfertilized ones develop into males (sometimes

called "drones"). Adult males do not participate in nest maintenance,

foraging, or caretaking of the larvae. In early to mid autumn, they

leave the nest and mate during "nuptial flights."

Other temperate species (e.g., the yellow hornet, V. simillima, or the Oriental hornet, V. orientalis) have similar cycles. In the case of tropical species (e.g., V. tropica), life histories may well differ, and in species with both tropical and temperate distributions (such as the Asian giant hornet, Vespa mandarinia), the cycle likely depends on latitude.

Distribution

Hornets are found mainly in the Northern Hemisphere. The common European hornet (Vespa crabro) is the best-known species, widely distributed in Europe (but is never found north of the 63rd parallel), Ukraine and European Russia (except in extreme northern areas). In the east, the species' distribution area stretches over the Ural Mountains to Western Siberia (found in the vicinity of Khanty-Mansiysk). In Asia, the common European hornet is found in southern Siberia, as well as in eastern China.

The common European hornet was accidentally introduced to eastern North

America about the middle of the 19th century and has lived there since

at about the same latitudes as in Europe. However, it has never been

found in western North America.

The Asian giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia) lives in the Primorsky Krai, Khabarovsky Krai (southern part) and Jewish AO regions of Russia, China, Korea, Taiwan, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Indochina, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Thailand, but is most commonly found in the mountains of Japan, where they are commonly known as the giant sparrow bee.

The Oriental hornet (Vespa orientalis) occurs in semi-dry sub-tropical areas of Central Asia (Armenia, Dagestan in Russia, Iran, Afghanistan, Oman, Pakistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrghyzstan, southern Kazakhstan), southern Europe (Italy, Malta, Albania, Romania, Turkey, Greece, Bulgaria, Cyprus), North Africa (Algeria, Libya, Egypt, Sudan, Eritrea, Somalia) and along the shores of the Gulf of Aden and in the Middle East. It has been introduced to Madagascar.

Stings

Hornets have stings

used to kill prey and defend nests. Hornet stings are more painful to

humans than typical wasp stings because hornet venom contains a large

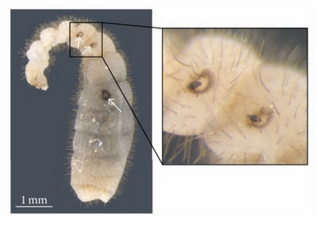

amount (5%) of acetylcholine. Individual hornets can sting repeatedly; unlike honey bees,

hornets do not die after stinging because their stingers are very

finely barbed (only visible under high magnification) and can easily be

withdrawn and so are not pulled out of their bodies when disengaging.

The toxicity of hornet stings varies according to hornet species;

some deliver just a typical insect sting, while others are among the

most venomous known insects. Single hornet stings are not in themselves fatal, except sometimes to allergic victims. Multiple stings by non-European hornets may be fatal because of highly toxic species-specific components of their venom.

The stings of the Asian giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia) are among the most venomous known,

and are thought to cause 30–50 human deaths annually in Japan. Between

July and September 2013, hornet stings caused the death of 42 people in

China. Asian giant hornet's venom can cause allergic reactions and multiple organ failure leading to death, though dialysis can be used to remove the toxins from the bloodstream.

People who are allergic to wasp venom are also allergic to hornet stings. Allergic reactions are commonly treated with epinephrine (adrenaline) injection using a device such as an epinephrine autoinjector, with prompt follow-up treatment in a hospital. In severe cases, allergic individuals may go into anaphylactic shock and die unless treated promptly.

Attack pheromone

Hornets,

like many social wasps, can mobilize the entire nest to sting in

defense, which is highly dangerous to humans and other animals. The

attack pheromone is released in case of threat to the nest. In the case of the Asian giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia) this is also used to mobilize many workers at once when attacking colonies of their prey, honey bees and other Vespa species. Three biologically active chemicals, 2-pentanol, 3-methyl-1-butanol,

and 1-methylbutyl 3-methylbutanoate, have been identified for this

species. In field tests, 2-pentanol alone triggered mild alarm and

defensive behavior, but adding the other two compounds increased

aggressiveness in a synergistic effect. In the European hornet (Vespa crabro) the major compound of the alarm pheromone is 2-methyl-3-butene-2-ol.

If a hornet is killed near a nest it may release pheromones that

can cause the other hornets to attack. Materials that come in contact

with these pheromones, such as clothes, skin, and dead prey or hornets,

can also trigger an attack, as can certain food flavorings, such as

banana and apple flavorings, and fragrances that contain C5 alcohols and C10 esters.

Diet and feeding

Adult hornets and their relatives (e.g., yellowjackets) feed themselves with nectar and sugar-rich plant foods. Thus, they can often be found feeding on the sap of oak trees,

rotting sweet fruits, honey and any sugar-containing foodstuffs.

Hornets frequently fly into orchards to feed on overripe fruit. Hornets

tend to gnaw a hole into fruit to become totally immersed into its pulp.

A person who accidentally plucks a fruit with a feeding hornet can be

attacked by the disturbed insect.

The adults also attack various insects, which they kill with

stings and jaws. Due to their size and the power of their venom, hornets

are able to kill large insects such as honey bees, grasshoppers, locusts and katydids without difficulty. The victim is fully masticated and then fed to the larvae

developing in the nest, rather than consumed by the adult hornets.

Given that some of their prey are considered pests, hornets may be

considered beneficial under some circumstances.

The larvae of hornets produce a sweet secretion containing sugars and amino acids that is consumed by the workers and queens.

Hornets and other Vespidae

European hornet with the remnants of a honey bee.

While taxonomically well defined, there may be some confusion about

the differences between hornets and other wasps of the family Vespidae, specifically the yellowjackets,

which are members of the same subfamily. Yellowjackets are generally

smaller than hornets and are bright yellow and black, whereas hornets

may often be black and white. There is also a related genus of Asian

nocturnal vespines, Provespa, which are referred to as "night wasps" or "night hornets", though they are not true hornets.

Some other large wasps are sometimes referred to as hornets, most notably the bald-faced hornet (Dolichovespula maculata)

found in North America. It is set apart by its black and ivory

coloration. The name "hornet" is used for this and related species

primarily because of their habit of making aerial nests (similar to the

true hornets) rather than subterranean nests. Another example is the Australian hornet (Abispa ephippium), which is actually a species of potter wasp.

Species (22 extant + 7 †fossil; not including subspecies)

- Vespa affinis

- Vespa analis

- Vespa basalis

- Vespa bellicosa

- Vespa bicolor

- †Vespa bilineata

- Vespa binghami

- †Vespa ciliata

- †Vespa cordifera

- Vespa crabro

- †Vespa crabroniformis

- †Vespa dasypodia

- Vespa ducalis

- Vespa dybowskii

- Vespa fervida

- Vespa fumida

- Vespa luctuosa

- Vespa mandarinia

- Vespa mocsaryana

- Vespa multimaculata

- †Vespa nigra

- Vespa orientalis

- Vespa philippinensis

- †Vespa picea

- Vespa simillima

- Vespa soror

- Vespa tropica

- Vespa velutina

- Vespa vivax

Notable species

- Asian giant hornet Vespa mandarinia

- Vespa mandarinia japonica (sometimes known as Japanese giant hornet) – the largest wasp, and the most venomous known insect (per sting).

- Asian predatory wasp Vespa velutina

- Black-bellied hornet Vespa basalis

- Black shield wasp Vespa bicolor

- European hornet Vespa crabro, (sometimes known as Old World Hornet, or Brown Hornet).

- Greater banded hornet Vespa tropica

- Japanese hornet Vespa simillima (sometimes known as Japanese yellow hornet).

- Lesser banded hornet Vespa affinis

- Oriental hornet Vespa orientalis

- Vespa luctuosa the most lethal wasp venom (per volume).

- Black hornet Vespa dybowskii

As food and medicine

Hornet larvae are widely accepted as food in mountainous regions in China.

Hornets and their nest are treated as medicine in Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Gallery

- Black-bellied hornet (Vespa basalis), Xingping

- Asian predatory wasp (Vespa velutina var. nigrithorax), Shanghai