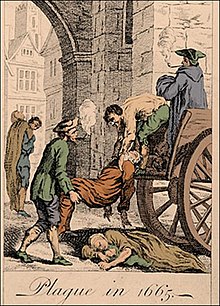

Collecting the dead for burial during the Great Plague

The Great Plague, lasting from 1665 to 1666, was the last major epidemic of the bubonic plague to occur in England. It happened within the centuries-long time period of the Second Pandemic, an extended period of intermittent bubonic plague epidemics which originated in China in 1331, the first year of the Black Death, an outbreak which included other forms such as pneumonic plague, and lasted until 1750.

The Great Plague killed an estimated 100,000 people—almost a quarter of London's population—in 18 months. The plague was caused by the Yersinia pestis bacterium, which is usually transmitted through the bite of an infected rat flea.

The 1665–66 epidemic was on a far smaller scale than the earlier Black Death pandemic;

it was remembered afterwards as the "great" plague mainly because it

was the last widespread outbreak of bubonic plague in England during the

400-year timespan of the Second Pandemic.

London in 1665

Map of London by Wenceslas Hollar, c.1665

As in other European cities of the period, the plague was endemic in 17th century London.

The disease periodically erupted into massive epidemics. There were

30,000 deaths due to the plague in 1603, 35,000 in 1625, and 10,000 in

1636, as well as smaller numbers in other years.

During the winter of 1664, a bright comet was to be seen in the sky

and the people of London were fearful, wondering what evil event it

portended. London at that time consisted of a city of about 448 acres

surrounded by a city wall, which had originally been built to keep out raiding bands. There were gates at Ludgate, Newgate, Aldersgate, Cripplegate, Moorgate and Bishopsgate and to the south lay the River Thames and London Bridge.

In the poorer parts of the city, hygiene was impossible to maintain in

the overcrowded tenements and garrets. There was no sanitation, and open

drains flowed along the centre of winding streets. The cobbles were

slippery with animal dung, rubbish and the slops thrown out of the

houses, muddy and buzzing with flies in summer and awash with sewage in

winter. The City Corporation

employed "rakers" to remove the worst of the filth and it was

transported to mounds outside the walls where it accumulated and

continued to decompose. The stench was overwhelming and people walked

around with handkerchiefs or nosegays pressed against their nostrils.

Some of the city's necessities such as coal arrived by barge,

but most came by road. Carts, carriages, horses and pedestrians were

crowded together and the gateways in the wall formed bottlenecks through

which it was difficult to progress. The nineteen-arch London Bridge was

even more congested. The better-off used hackney carriages and sedan chairs

to get to their destinations without getting filthy. The poor walked,

and might be splashed by the wheeled vehicles and drenched by slops

being thrown out and water falling from the overhanging roofs. Another

hazard was the choking black smoke belching forth from factories which

made soap, from breweries and iron smelters and from about 15,000 houses burning coal.

Scenes in London during the plague of 1665

Outside the city walls, suburbs had sprung up providing homes for the

craftsmen and tradespeople who flocked to the already overcrowded city.

These were shanty towns

with wooden shacks and no sanitation. The government had tried to

control this development but had failed and over a quarter of a million

people lived here. Other immigrants had taken over fine town houses, vacated by Royalists who had fled the country during the Commonwealth,

converting them into tenements with different families in every room.

These properties were soon vandalised and became rat-infested slums.

The administration of the City of London was organised by the

Lord Mayor, Aldermen and common councillors, but not all of the

inhabited area generally comprising London was legally part of the City.

Both inside the City and outside its boundaries there were also Liberties,

which were areas of varying sizes which historically had been granted

rights to self-government. Many had been associated with religious

institutions, and when these were abolished in the Dissolution of the Monasteries,

their historic rights were transferred along with their property to new

owners. The walled City was surrounded by a ring of Liberties which had

come under its authority, contemporarily called 'the City and

Liberties', but these were surrounded by further suburbs with varying

administrations. Westminster was an independent town with its own liberties, although it was joined to London by urban development. The Tower of London

was an independent liberty, as were others. Areas north of the river

not part of one of these administrations came under the authority of the

county of Middlesex, and south of the river under Surrey.

The "Woodcut" map of London, dating from the 1560s

At that time, bubonic plague was a much feared disease but its cause

was not understood. The credulous blamed emanations from the earth,

"pestilential effluviums", unusual weather, sickness in livestock,

abnormal behaviour of animals or an increase in the numbers of moles,

frogs, mice or flies. It was not until 1894 that the identification by Alexandre Yersin of its causal agent Yersinia pestis was made and the transmission of the bacterium by rat fleas became known. Although the Great Plague in London had long been believed to be bubonic plague caused by Yersinia pestis, this was only definitively confirmed by DNA analysis in 2016.

The recording of deaths

In order to judge the severity of an epidemic, it is first necessary

to know how big the population was in which it occurred. There was no

official census of the population to provide this figure, and the best

contemporary count comes from the work of John Graunt (1620–1674), who was one of the earliest Fellows of the Royal Society and one of the first demographers,

bringing a scientific approach to the collection of statistics. In

1662, he estimated that 384,000 people lived in the City of London, the

Liberties, Westminster and the out-parishes, based on figures in the bills of mortality

published each week in the capital. These different districts with

different administrations constituted the officially recognized extent

of London as a whole. In 1665, he revised his estimate to 'not above

460,000'. Other contemporaries put the figure higher, (the French

Ambassador, for example, suggested 600,000) but with no mathematical

basis to support their estimates. The next largest city in the kingdom

was Norwich, with a population of 30,000.

There was no duty to report a death to anyone in authority. Instead, each parish appointed two or more 'searchers of the dead',

whose duty was to inspect a corpse and determine the cause of death. A

searcher was entitled to charge a small fee from relatives for each

death they reported, and so habitually the parish would appoint someone

to the post who would otherwise be destitute and would be receiving

support from the parish poor rate. Typically, this meant searchers would

be old women who were illiterate, might know little about identifying

diseases and who would be open to dishonesty. Searchers would typically learn about a death either from the local sexton

who had been asked to dig a grave or from the tolling of a church bell.

Anyone who did not report a death to their local church, such as Quakers, Anabaptists, other non-Anglican Christians or Jews,

frequently did not get included in the official records. Searchers

during times of plague were required to live apart from the community,

avoid other people and carry a white stick to warn of their occupation

when outdoors, and stay indoors except when performing their duties, to

avoid spreading the diseases. Searchers reported to the Parish Clerk,

who made a return each week to the Company of Parish Clerks in Brode

Lane. Figures were then passed to the Lord Mayor and then to the

Minister of State once plague became a matter of national concern. The reported figures were used to compile the Bills of Mortality,

which listed total deaths in each parish and whether by the plague. The

system of Searchers to report the cause of death continued until 1836.

Graunt recorded the incompetence of the Searchers at identifying

true causes of death, remarking on the frequent recording of

'consumption' rather than other diseases which were recognized then by

physicians. He suggested a cup of ale and a doubling of their fee to two

groats rather than one was sufficient for Searchers to change the cause

of death to one more convenient for the householders. No one wished to

be known as having had a death by plague in their household, and Parish

Clerks, too, connived in covering up cases of plague in their official

returns. Analysis of the Bills of Mortality during the months plague

took hold shows a rise in deaths other than by plague well above the

average death rate, which has been attributed to misrepresentation of

the true cause of death. As plague spread, a system of quarantine

was introduced, whereby any house where someone had died from plague

would be locked up and no one allowed to enter or leave for 40 days.

This frequently led to the deaths of the other inhabitants, by neglect

if not from the plague, and provided ample incentive not to report the

disease. The official returns record 68,596 cases of plague, but a

reasonable estimate suggests this figure is 30,000 short of the true

total. A plague house was marked with a red cross on the door with the words "Lord have mercy upon us", and a watchman stood guard outside.

Preventive measures

Reports

of plague around Europe began to reach England in the 1660s, causing

the Privy Council to consider what steps might be taken to prevent it

crossing to England. Quarantining of ships had been used during previous

outbreaks and was again introduced for ships coming to London in

November 1663, following outbreaks in Amsterdam and Hamburg.

Two naval ships were assigned to intercept any vessels entering the

Thames estuary. Ships from infected ports were required to moor at Hole

Haven on Canvey Island

for a period of 30 days before being allowed to travel upriver. Ships

from ports free of plague or completing their quarantine were given a

certificate of health and allowed to travel on. A second inspection

line was established between the forts on opposite banks of the Thames

at Tilbury and Gravesend with instructions only to pass ships with a certificate.

The quarantine duration was increased to forty days in May 1664

as the continental plague worsened, and the areas subject to quarantine

changed with the news of the spread of plague to include all of Holland, Zeeland and Friesland (all regions of the Dutch Republic),

although restrictions on Hamburg were removed in November. Quarantine

measures against ships coming from the Dutch Republic were put in place

in 29 other ports from May, commencing with Great Yarmouth.

The Dutch ambassador objected at the constraint of trade with his

country, but England responded that it had been one of the last

countries introducing such restrictions. Regulations were enforced quite

strictly, so that people or houses where voyagers had come ashore

without serving their quarantine were also subjected to 40 days of

quarantine.

Outbreak

Plague was one of the hazards of life in Britain from its dramatic

appearance in 1348 with the Black Death. The Bills of Mortality began to

be published regularly in 1603, in which year 33,347 deaths were

recorded from plague. Between then and 1665, only four years had no

recorded cases. In 1563, a thousand people were reportedly dying in

London each week. In 1593, there were 15,003 deaths, 1625 saw 41,313

dead, between 1640 and 1646 came 11,000 deaths, culminating in 3,597

for 1647. The 1625 outbreak was recorded at the time as the 'Great

Plague', until deaths from the plague of 1665 surpassed it. These

official figures are likely to under-report actual numbers.

Early days

Rattus rattus,

the Black Rat. Smaller than the Norwegian rat, which later supplanted

it, it is also keener to live near to humankind. Timber houses and

overcrowded slums provided great homes. The link between the rat as

reservoir of infection and host to fleas which could transfer to man was

not understood. Efforts were made to eliminate cats and dogs but not

rats. If anything, this encouraged the rats.

Although plague was known, it was still sufficiently uncommon that

medical practitioners might have had no personal experience of seeing

the disease; medical training varied from those who had attended the

college of physicians, to apothecaries who also acted as modern doctors,

to simple charlatans. Other diseases abounded, such as an outbreak of

smallpox the year before, and these uncertainties all added to

difficulties identifying the true start of the epidemic.

Contemporary accounts suggest cases of plague occurred through the

winter of 1664/5, some of which were fatal but a number of which did not

display the virulence of the later epidemic. The winter was cold, the

ground frozen from December to March, river traffic on the Thames twice

blocked by ice, and it may be that the cold weather held back its

spread.

This outbreak of bubonic plague in England is thought to have spread from the Netherlands,

where the disease had been occurring intermittently since 1599. It is

unclear exactly where the disease first struck but the initial contagion

may have arrived with Dutch trading ships carrying bales of cotton from Amsterdam, which was ravaged by the disease in 1663–1664, with a mortality given of 50,000. The first areas to be struck are believed to be the dock areas just outside London, and the parish of St Giles.

In both of these localities, poor workers were crowded into ill-kept

structures. Two suspicious deaths were recorded in St. Giles parish in 1664 and another in February 1665. These did not appear as plague deaths on the Bills of Mortality,

so no control measures were taken by the authorities, but the total

number of people dying in London during the first four months of 1665

showed a marked increase. By the end of April, only four plague deaths

had been recorded, two in the parish of St. Giles, but total deaths per

week had risen from around 290 to 398.

Although there had been only three official cases in April, which

level of plague in earlier years had not induced any official response,

the Privy Council now acted to introduce household quarantine. Justices

of the Peace in Middlesex were instructed to investigate any suspected

cases and to shut up the house if it was confirmed. Shortly after, a

similar order was issued by the King's Bench to the City and Liberties. A

riot broke out in St. Giles when the first house was sealed up; the

crowd broke down the door and released the inhabitants. Rioters caught

were punished severely. Instructions were given to build pest-houses,

which were essentially isolation hospitals built away from other people

where the sick could be cared for (or stay until they died). This

official activity suggests that despite the few recorded cases, the

government was already aware that this was a serious outbreak of plague.

With the arrival of warmer weather, the disease began to take a

firmer hold. In the week 2–9 May, there were three recorded deaths in

the parish of St Giles, four in neighbouring St Clement Danes and one each in St Andrew Holborn and St Mary Woolchurch Haw.

Only the last was actually inside the city walls. A Privy Council

committee was formed to investigate methods to best prevent the spread

of plague, and measures were introduced to close some of the ale houses

in affected areas and limit the number of lodgers allowed in a

household. In the city, the Lord Mayor issued a proclamation that all

householders must diligently clean the streets outside their property,

which was a householder's responsibility, not a state one (the city

employed scavengers and rakers to remove the worst of the mess). Matters

just became worse, and Aldermen were instructed to find and punish

those failing their duty.

As cases in St. Giles began to rise, an attempt was made to quarantine

the area and constables were instructed to inspect everyone wishing to

travel and contain inside vagrants or suspect persons.

People began to be alarmed. Samuel Pepys, who had an important position at the Admiralty, stayed in London and provided a contemporary account of the plague through his diary.

On 30 April he wrote: "Great fears of the sickness here in the City it

being said that two or three houses are already shut up. God preserve us

all!" Another source of information on the time is A Journal of the Plague Year, which was written by Daniel Defoe

and published in 1722. He had been only six when the plague struck but

made use of his family's recollections (his uncle was a saddler in East

London and his father a butcher in Cripplegate), interviews with survivors and sight of such official records as were available.

Exodus from the city

By July 1665, plague was rampant in the City of London. The rich ran away, including King Charles II of England, his family and his court, who left the city for Salisbury, moving on to Oxford in September when some cases of plague occurred in Salisbury. The aldermen and most of the other city authorities opted to stay at their posts. The Lord Mayor of London, Sir John Lawrence,

also decided to stay in the city. Businesses were closed when merchants

and professionals fled. Defoe wrote "Nothing was to be seen but wagons

and carts, with goods, women, servants, children, coaches filled with

people of the better sort, and horsemen attending them, and all hurrying

away". As the plague raged throughout the summer, only a small number of clergymen, physicians and apothecaries remained to cope with an increasingly large number of victims. Edward Cotes, author of London's Dreadful Visitation, expressed the hope that "Neither the Physicians of our Souls or Bodies may hereafter in such great numbers forsake us".

The poorer people were also alarmed by the contagion and some

left the city, but it was not easy for them to abandon their

accommodation and livelihoods for an uncertain future elsewhere. Before

exiting through the city gates, they were required to possess a

certificate of good health signed by the Lord Mayor and these became

increasingly difficult to obtain. As time went by and the numbers of

plague victims rose, people living in the villages outside London began

to resent this exodus and were no longer prepared to accept townsfolk

from London, with or without a certificate. The refugees were turned

back, were not allowed to pass through towns and had to travel across

country, and were forced to live rough on what they could steal or

scavenge from the fields. Many died in wretched circumstances of

starvation and thirst in the hot summer that was to follow.

Height of the epidemic

A bill of mortality for the plague in 1665

In the last week of July, the London Bill of Mortality showed 3,014

deaths, of which 2,020 had died from the plague. The number of deaths as

a result of plague may have been underestimated, as deaths in other

years in the same period were much lower, at around 300. As the number

of victims affected mounted up, burial grounds became overfull, and pits

were dug to accommodate the dead. Drivers of dead-carts travelled the

streets calling "Bring out your dead" and carted away piles of bodies.

The authorities became concerned that the number of deaths might cause

public alarm and ordered that body removal and interment should take

place only at night.

As time went on, there were too many victims, and too few drivers, to

remove the bodies which began to be stacked up against the walls of

houses. Daytime collection was resumed and the plague pits became mounds

of decomposing corpses. In the parish of Aldgate, a great hole was dug

near the churchyard, fifty feet long and twenty feet wide. Digging was

continued by labourers at one end while the dead-carts tipped in corpses

at the other. When there was no room for further extension it was dug

deeper until ground water was reached at twenty feet. When finally

covered with earth it housed 1,114 corpses.

Plague doctors traversed the streets diagnosing victims, although many of them had no formal medical training. Several public health

efforts were attempted. Physicians were hired by city officials and

burial details were carefully organized, but panic spread through the

city and, out of the fear of contagion, people were hastily buried in

overcrowded pits. The means of transmission of the disease were not

known but thinking they might be linked to the animals, the City

Corporation ordered a cull of dogs and cats.

This decision may have affected the length of the epidemic since those

animals could have helped keep in check the rat population carrying the

fleas which transmitted the disease. Thinking bad air was involved in

transmission, the authorities ordered giant bonfires to be burned in the

streets and house fires to be kept burning night and day, in hopes that

the air would be cleansed. Tobacco was thought to be a prophylactic and it was later said that no London tobacconist had died from the plague during the epidemic.

Trade and business had completely dried up, and the streets were

empty of people except for the dead-carts and the desperate dying

victims, as witnessed and recorded by Samuel Pepys in his diary: "Lord!

How empty the streets are and how melancholy, so many poor sick people

in the streets full of sores… in Westminster, there is never a physician

and but one apothecary left, all being dead." That people did not starve was down to the foresight of Sir John Lawrence and the Corporation of London who arranged for a commission of one farthing to be paid above the normal price for every quarter of corn landed in the Port of London.

Another food source was the villages around London which, denied of

their usual sales in the capital, left vegetables in specified market

areas, negotiated their sale by shouting, and collected their payment

after the money had been left submerged in a bucket of water to

"disinfect" the coins.

Records state that plague deaths in London and the suburbs crept

up over the summer from 2,000 people per week to over 7,000 per week in

September. These figures are likely to be a considerable underestimate.

Many of the sextons and parish clerks who kept the records themselves

died. Quakers

refused to co-operate and many of the poor were just dumped into mass

graves unrecorded. It is not clear how many people caught the disease

and made a recovery because only deaths were recorded and many records

were destroyed in the Great Fire of London

the following year. In the few districts where intact records remain,

plague deaths varied between 30% and over 50% of the total population.

Although concentrated in London, the outbreak affected other

areas of the country as well. Perhaps the most famous example was the

village of Eyam in Derbyshire.

The plague allegedly arrived with a merchant carrying a parcel of cloth

sent from London, although this is a disputed point. The villagers

imposed a quarantine on themselves to stop the further spread of the

disease. This prevented the disease from moving into surrounding areas,

but around 33% of the village's inhabitants died over a period of

fourteen months.

Aftermath

By late autumn, the death toll in London and the suburbs began to

slow until, in February 1666, it was considered safe enough for the King

and his entourage to come back to the city. With the return of the

monarch, others began to return: The gentry returned in their carriages

accompanied by carts piled high with their belongings. The judges moved

back from Windsor to sit in Westminster Hall, although Parliament, which had been prorogued

in April 1665, did not reconvene until September 1666. Trade

recommenced and businesses and workshops opened up. London was the goal

of a new wave of people who flocked to the city in expectation of making

their fortunes. Writing at the end of March 1666, Lord Clarendon, the Lord Chancellor,

stated "... the streets were as full, the Exchange as much crowded, the

people in all places as numerous as they had ever been seen ...".

Plague cases continued to occur sporadically at a modest rate

until the summer of 1666. On the second and third of September that

year, the Great Fire of London

destroyed much of the City of London, and some people believed that the

fire put an end to the epidemic. However, it is now thought that the

plague had largely subsided before the fire took place. In fact, most of

the later cases of plague were found in the suburbs, and it was the City of London itself that was destroyed by the Fire.

According to the Bills of Mortality, there were in total 68,596

deaths in London from the plague in 1665. Lord Clarendon estimated that

the true number of mortalities was probably twice that figure. The next

year, 1666, saw further deaths in other cities but on a lesser scale. Dr Thomas Gumble, chaplain to the Duke of Albemarle,

both of whom had stayed in London for the whole of the epidemic,

estimated that the total death count for the country from plague during

1665 and 1666 was about 200,000.

The Great Plague of 1665/1666 was the last major outbreak of bubonic plague

in Great Britain. The last recorded death from plague came in 1679, and

it was removed as a specific category in the Bills of Mortality after

1703. It spread to other towns in East Anglia and the southeast of

England but fewer than ten percent of parishes outside London had a

higher than average death rate during those years. Urban areas were more

affected than rural ones; Norwich, Ipswich, Colchester, Southampton and

Winchester were badly affected, while the West of England and areas of

the Midlands escaped altogether.

The population of England in 1650 was approximately 5.25 million,

which declined to about 4.9 million by 1680, recovering to just over 5

million by 1700. Other diseases, such as smallpox, took a high toll on

the population even without the contribution by plague. The higher death

rate in cities, both generally and specifically from the plague, was

made up by continuous immigration, from small towns to larger ones and

from the countryside to the town.

There were no contemporary censuses of London's population, but

available records suggest that the population returned to its previous

level within a couple of years. Burials in 1667 had returned to 1663

levels, Hearth Tax returns had recovered, John Graunt contemporarily

analysed baptism records and concluded they represented a recovered

population. Part of this could be accounted for by the return of wealthy

households, merchants and manufacturing industries, all of which needed

to replace losses among their staff and took steps to bring in

necessary people. Colchester had suffered more severe depopulation, but

manufacturing records for cloth suggested that production had recovered

or even increased by 1669, and the total population had nearly returned

to pre-plague levels by 1674. Other towns did less well: Ipswich was

affected less than Colchester, but in 1674, its population had dropped

by 18%, more than could be accounted for by the plague deaths alone.

As a proportion of the population who died, the London death toll

was less severe than in a number of other towns. The total of deaths in

London was greater than in any previous outbreak for 100 years, though

as a proportion of the population, the epidemics in 1563, 1603 and 1625

were comparable or greater. Perhaps around 2.5% of the English

population died.

Impact

The

plague in London largely affected the poor, as the rich were able to

leave the city by either retiring to their country estates or residing

with kin in other parts of the country. The subsequent Great Fire of London, however, ruined many city merchants and property owners. As a result of these events, London was largely rebuilt and Parliament enacted the Rebuilding of London Act 1666.

Although the street plan of the capital remained relatively unchanged,

some improvements were made: streets were widened, pavements were

created, open sewers abolished, wooden buildings and overhanging gables

forbidden, and the design and construction of buildings controlled. The

use of brick or stone was mandatory and many gracious buildings were

constructed. Not only was the capital rejuvenated, but it became a

healthier environment in which to live. Londoners had a greater sense of

community after they had overcome the great adversities of 1665 and

1666.

Rebuilding took over ten years and was supervised by Robert Hooke as Surveyor of London. The architect Sir Christopher Wren was involved in the rebuilding of St Paul's Cathedral and more than fifty London churches. King Charles ll did much to foster the rebuilding work. He was a patron of the arts and sciences and founded the Royal Observatory and supported the Royal Society, a scientific group whose early members included Robert Hooke, Robert Boyle and Sir Isaac Newton. In fact, out of the fire and pestilence flowed a renaissance in the arts and sciences in England.

Plague pits have been archaeologically excavated during underground construction work. Between 2011 and 2015, some 3,500 burials from the 'New Churchyard' or 'Bethlam burial ground' were discovered during the construction of the Crossrail railway at Liverpool Street. Yersinia pestis DNA was found in the teeth of individuals found buried in pits at the site, confirming they had died of bubonic plague.