| Sepsis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Septicemia, blood poisoning |

| |

| Blood culture bottles: orange cap for anaerobes, green cap for aerobes, and yellow cap for blood samples from children | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, increased heart rate, low blood pressure, increased breathing rate, confusion |

| Causes | Immune response triggered by an infection |

| Risk factors | Young or old age, cancer, diabetes, major trauma, burns |

| Diagnostic method | Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS),[3] qSOFA[5] |

| Treatment | Intravenous fluids, antimicrobials |

| Prognosis | 10 to 80% risk of death |

| Frequency | 0.2–3 per 1000 a year (developed world) |

Sepsis is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its tissues and organs. Common signs and symptoms include fever, increased heart rate, increased breathing rate, and confusion. There may also be symptoms related to a specific infection, such as a cough with pneumonia, or painful urination with a kidney infection. The very young, old, and people with a weakened immune system may have no symptoms of a specific infection, and the body temperature may be low or normal instead of having a fever. Severe sepsis is sepsis causing poor organ function or blood flow. The presence of low blood pressure, high blood lactate, or low urine output may suggest poor blood flow. Septic shock is low blood pressure due to sepsis that does not improve after fluid replacement.

Sepsis is an inflammatory immune response triggered by an infection. Bacterial infections are the most common cause, but fungal, viral, and protozoan infections can also lead to sepsis. Common locations for the primary infection include the lungs, brain, urinary tract, skin, and abdominal organs. Risk factors include being very young, older age, a weakened immune system from conditions such as cancer or diabetes, major trauma, or burns. Previously, a sepsis diagnosis required the presence of at least two systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria in the setting of presumed infection. In 2016, a shortened sequential organ failure assessment score (SOFA score), known as the quick SOFA score (qSOFA), replaced the SIRS system of diagnosis. qSOFA criteria for sepsis include at least two of the following three: increased breathing rate, change in the level of consciousness, and low blood pressure. Sepsis guidelines recommend obtaining blood cultures before starting antibiotics; however, the diagnosis does not require the blood to be infected. Medical imaging is helpful when looking for the possible location of the infection. Other potential causes of similar signs and symptoms include anaphylaxis, adrenal insufficiency, low blood volume, heart failure, and pulmonary embolism.

Sepsis requires immediate treatment with intravenous fluids and antimicrobials. Ongoing care often continues in an intensive care unit. If an adequate trial of fluid replacement is not enough to maintain blood pressure, then the use of medications that raise blood pressure becomes necessary. Mechanical ventilation and dialysis may be needed to support the function of the lungs and kidneys, respectively.

A central venous catheter and an arterial catheter may be placed for access to the bloodstream and to guide treatment. Other helpful measurements include cardiac output and superior vena cava oxygen saturation. People with sepsis need preventive measures for deep vein thrombosis, stress ulcers, and pressure ulcers unless other conditions prevent such interventions. Some might benefit from tight control of blood sugar levels with insulin. The use of corticosteroids is controversial, with some reviews finding benefit, and others not.

Disease severity partly determines the outcome. The risk of death from sepsis is as high as 30%, as high as 50% from severe sepsis, and up to 80% from septic shock. Sepsis affected about 49 million people in 2017, with 11 million deaths (1 in 5 deaths worldwide). In the developed world, approximately 0.2 to 3 people per 1000 are affected by sepsis yearly, resulting in about a million cases per year in the United States. Rates of disease have been increasing. Sepsis is more common among males than females. Descriptions of sepsis date back to the time of Hippocrates. The terms "septicemia" and "blood poisoning" have been used in various ways and are no longer recommended.

Signs and symptoms

In addition to symptoms related to the actual cause, people with sepsis may have a fever, low body temperature, rapid breathing, a fast heart rate, confusion, and edema. Early signs include a rapid heart rate, decreased urination, and high blood sugar. Signs of established sepsis include confusion, metabolic acidosis (which may be accompanied by a faster breathing rate that leads to respiratory alkalosis), low blood pressure due to decreased systemic vascular resistance, higher cardiac output, and disorders in blood-clotting that may lead to organ failure.

The drop in blood pressure seen in sepsis can cause lightheadedness and is part of the criteria for septic shock.

Cause

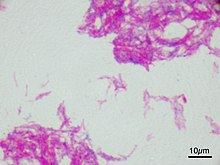

Infections leading to sepsis are usually bacterial but may be fungal or viral. Gram-positive bacteria were the primary cause of sepsis before the introduction of antibiotics in the 1950s. After the introduction of antibiotics, gram-negative bacteria became the predominant cause of sepsis from the 1960s to the 1980s. After the 1980s, gram-positive bacteria, most commonly staphylococci, are thought to cause more than 50% of cases of sepsis. Other commonly implicated bacteria include Streptococcus pyogenes, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella species. Fungal sepsis

accounts for approximately 5% of severe sepsis and septic shock cases;

the most common cause of fungal sepsis is an infection by Candida species of yeast, a frequent hospital-acquired infection.

The most common sites of infection resulting in severe sepsis are the lungs, the abdomen, and the urinary tract.

Typically, 50% of all sepsis cases start as an infection in the lungs.

In one third to one-half of cases, the source of infection is unclear.

Diagnosis

Early

diagnosis is necessary to properly manage sepsis, as the initiation of

rapid therapy is key to reducing deaths from severe sepsis. Some hospitals use alerts generated from electronic health records to bring attention to potential cases as early as possible.

Within the first three hours of suspected sepsis, diagnostic studies should include white blood cell counts,

measuring serum lactate, and obtaining appropriate cultures before

starting antibiotics, so long as this does not delay their use by more

than 45 minutes. To identify the causative organism(s), at least two sets of blood cultures using bottles with media for aerobic and anaerobic organisms are necessary. At least one should be drawn through the skin and one through each vascular access device (such as an IV catheter) that has been in place more than 48 hours. Bacteria are present in the blood in only about 30% of cases. Another possible method of detection is by polymerase chain reaction.

If other sources of infection are suspected, cultures of these sources,

such as urine, cerebrospinal fluid, wounds, or respiratory secretions,

also should be obtained, as long as this does not delay the use of

antibiotics.

Within six hours, if blood pressure remains low despite initial

fluid resuscitation of 30 ml/kg, or if initial lactate is ≥ four mmol/l

(36 mg/dl), central venous pressure and central venous oxygen saturation should be measured. Lactate should be re-measured if the initial lactate was elevated. Evidence for point of care lactate measurement over usual methods of measurement, however, is poor.

Within twelve hours, it is essential to diagnose or exclude any

source of infection that would require emergent source control, such as a

necrotizing soft tissue infection, an infection causing inflammation of the abdominal cavity lining, an infection of the bile duct, or an intestinal infarction. A pierced internal organ (free air on an abdominal x-ray or CT scan), an abnormal chest x-ray consistent with pneumonia (with focal opacification), or petechiae, purpura, or purpura fulminans may indicate the presence of an infection.

Definitions

| Finding | Value |

|---|---|

| Temperature | <36 nbsp="" or="">38 °C (100.4 °F) |

| Heart rate | >90/min |

| Respiratory rate | >20/min or PaCO2<32 font="" kpa="" mmhg="" nbsp=""> |

| WBC | <4x10 sup="">9 |

Sepsis Steps. Training tool for teaching the progression of sepsis stages

Previously, SIRS criteria had been used to define sepsis. If the SIRS

criteria are negative, it is very unlikely the person has sepsis; if it

is positive, there is just a moderate probability that the person has

sepsis. According to SIRS, there were different levels of sepsis:

sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock. The definition of SIRS is shown below:

- SIRS is the presence of two or more of the following: abnormal body temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, or blood gas, and white blood cell count.

- Sepsis is defined as SIRS in response to an infectious process.

- Severe sepsis is defined as sepsis with sepsis-induced organ dysfunction or tissue hypoperfusion (manifesting as hypotension, elevated lactate, or decreased urine output). Severe sepsis is an infectious disease state associated with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS)

- Septic shock is severe sepsis plus persistently low blood pressure, despite the administration of intravenous fluids.

In 2016 a new consensus was reached to replace screening by systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) with qSOFA. However, the American College of Chest Physicians

(CHEST) raised concerns that qSOFA and SOFA criteria may lead to

delayed diagnosis of serious infection, leading to delayed treatment.

Although SIRS criteria can be too sensitive and not specific enough in

identifying sepsis, SOFA also has its limitations and is not intended to

replace the SIRS definition.

qSOFA has also been found to be poorly sensitive though decently

specific for the risk of death with SIRS possibly better for screening.

End-organ dysfunction

Examples of end-organ dysfunction include the following:

- Lungs: acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (PaO2/FiO2 ratio< 300), different ratio in pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Brain: encephalopathy symptoms including agitation, confusion, coma; causes may include ischemia, bleeding, formation of blood clots in small blood vessels, microabscesses, multifocal necrotizing leukoencephalopathy

- Liver: disruption of protein synthetic function manifests acutely as progressive disruption of blood clotting due to an inability to synthesize clotting factors and disruption of metabolic functions leads to impaired bilirubin metabolism, resulting in elevated unconjugated serum bilirubin levels

- Kidney: low urine output or no urine output, electrolyte abnormalities, or volume overload

- Heart: systolic and diastolic heart failure, likely due to chemical signals that depress myocyte function, cellular damage, manifest as a troponin leak (although not necessarily ischemic in nature)

More specific definitions of end-organ dysfunction exist for SIRS in pediatrics.

- Cardiovascular dysfunction (after fluid resuscitation with at least 40 ml/kg of crystalloid)

- hypotension with blood pressure < 5th percentile for age or systolic blood pressure < 2 standard deviations below normal for age, or

- vasopressor requirement, or

- two of the following criteria:

- unexplained metabolic acidosis with base deficit > 5 mEq/l

- lactic acidosis: serum lactate 2 times the upper limit of normal

- oliguria (urine output < 0.5 ml/kg/h)

- prolonged capillary refill > 5 seconds

- core to peripheral temperature difference > 3 °C

- Respiratory dysfunction (in the absence of a cyanotic heart defect or a known chronic respiratory disease)

- the ratio of the arterial partial-pressure of oxygen to the fraction of oxygen in the gases inspired (PaO2/FiO2) < 300 (the definition of acute lung injury), or

- arterial partial-pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) > 65 torr (20 mmHg) over baseline PaCO2 (evidence of hypercapnic respiratory failure), or

- supplemental oxygen requirement of greater than FiO2 0.5 to maintain oxygen saturation ≥ 92%

- Neurologic dysfunction

- Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) ≤ 11, or

- altered mental status with drop in GCS of 3 or more points in a person with developmental delay/intellectual disability

- Hematologic dysfunction

- platelet count < 80,000/mm3 or 50% drop from maximum in chronically thrombocytopenic, or

- international normalized ratio (INR) > 2

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- Kidney dysfunction

- serum creatinine ≥ 2 times the upper limit of normal for age or 2-fold increase in baseline creatinine in people with chronic kidney disease

- Liver dysfunction (only applicable to infants > 1 month)

- total serum bilirubin ≥ 4 mg/dl, or

- alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ≥ 2 times the upper limit of normal

Consensus definitions, however, continue to evolve, with the latest

expanding the list of signs and symptoms of sepsis to reflect clinical

bedside experience.

Biomarkers

A 2013 review concluded moderate-quality evidence exists to support the use of the procalcitonin level as a method to distinguish sepsis from non-infectious causes of SIRS. The same review found the sensitivity

of the test to be 77% and the specificity to be 79%. The authors

suggested that procalcitonin may serve as a helpful diagnostic marker

for sepsis, but cautioned that its level alone does not definitively

make the diagnosis. A 2012 systematic review found that soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (SuPAR) is a nonspecific marker of inflammation and does not accurately diagnose sepsis.

This same review concluded, however, that SuPAR has prognostic value,

as higher SuPAR levels are associated with an increased rate of death in

those with sepsis.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for sepsis is broad and has to examine (to exclude) the non-infectious conditions that may cause the systemic signs of SIRS: alcohol withdrawal, acute pancreatitis, burns, pulmonary embolism, thyrotoxicosis, anaphylaxis, adrenal insufficiency, and neurogenic shock. Hyperinflammatory syndromes such as hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) may have similar symptoms and are on the differential diagnosis.

Neonatal sepsis

In common clinical usage, neonatal sepsis refers to a bacterial blood stream infection in the first month of life, such as meningitis, pneumonia, pyelonephritis, or gastroenteritis, but neonatal sepsis also may be due to infection with fungi, viruses, or parasites.

Criteria with regard to hemodynamic compromise or respiratory failure

are not useful because they present too late for intervention.

Pathophysiology

Sepsis is caused by a combination of factors related to the

particular invading pathogen(s) and to the status of the immune system

of the host. The early phase of sepsis characterized by excessive inflammation (sometimes resulting in a cytokine storm) may be followed by a prolonged period of decreased functioning of the immune system.

Either of these phases may prove fatal. On the other hand, systemic

inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) occurs in people without the

presence of infection, for example, in those with burns, polytrauma, or the initial state in pancreatitis and chemical pneumonitis. However, sepsis also causes similar response to SIRS.

Microbial factors

Bacterial virulence factors, such as glycocalyx and various adhesins, allow colonization, immune evasion, and establishment of disease in the host. Sepsis caused by gram-negative bacteria is thought to be largely due to a response by the host to the lipid A component of lipopolysaccharide, also called endotoxin. Sepsis caused by gram-positive bacteria may result from an immunological response to cell wall lipoteichoic acid. Bacterial exotoxins that act as superantigens also may cause sepsis. Superantigens simultaneously bind major histocompatibility complex and T-cell receptors in the absence of antigen presentation. This forced receptor interaction induces the production of pro-inflammatory chemical signals (cytokines) by T-cells.

There are a number of microbial factors that may cause the typical septic inflammatory cascade. An invading pathogen is recognized by its pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Examples of PAMPs include lipopolysaccharides and flagellin in gram-negative bacteria, muramyl dipeptide in the peptidoglycan of the gram-positive bacterial cell wall, and CpG bacterial DNA. These PAMPs are recognized by the pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) of the innate immune system, which may be membrane-bound or cytosolic. There are four families of PRRs: the toll-like receptors, the C-type lectin receptors, the NOD-like receptors, and the RIG-I-like receptors.

Invariably, the association of a PAMP and a PRR will cause a series of

intracellular signalling cascades. Consequentially, transcription

factors such as nuclear factor-kappa B and activator protein-1, will up-regulate the expression of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines.

Host factors

Upon detection of microbial antigens,

the host systemic immune system is activated. Immune cells not only

recognise pathogen-associated molecular patterns, but also damage-associated molecular patterns from damaged tissues. An uncontrolled immune response is then activated because leukocytes are not recruited to the specific site of infection, but instead they are recruited all over the body. Then, an immunosuppression state ensues when the proinflammatory T helper cell 1 (TH1) is shifted to TH2, mediated by interleukin 10, which is known as "compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome". The apoptosis (cell death) of lymphocytes further worsens the immunosuppression. Subsequently, multiple organ failure ensues because tissues are unable to use oxygen efficiently due to inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase.

Inflammatory responses cause multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

through various mechanisms as described below. Increased permeability

of the lung vessels causes leaking of fluids into alveoli, which results

in pulmonary edema and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Impaired utilization of oxygen in the liver impairs bile salt transport, causing jaundice

(yellowish discoloration of skin). In kidneys, inadequate oxygenation

results in tubular epithelial cell injury (of the cells lining the

kidney tubules), and thus causes acute kidney injury (AKI). Meanwhile, in the heart, impaired calcium transport, and low production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), can cause myocardial depression, reducing cardiac contractility and causing heart failure. In the gastrointestinal tract, increased permeability of the mucosa alters the microflora, causing mucosal bleeding and paralytic ileus. In the central nervous system, direct damage of the brain cells and disturbances of neurotransmissions causes altered mental status. Cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor, interleukin 1, and interleukin 6 may activate procoagulation factors in the cells lining blood vessels, leading to endothelial damage. The damaged endothelial surface inhibits anticoagulant properties as well as increases antifibrinolysis, which may lead to intravascular clotting, the formation of blood clots in small blood vessels, and multiple organ failure.

The low blood pressure seen in those with sepsis is the result of

various processes, including excessive production of chemicals that dilate blood vessels such as nitric oxide, a deficiency of chemicals that constrict blood vessels such as vasopressin, and activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. In those with severe sepsis and septic shock, this sequence of events leads to a type of circulatory shock known as distributive shock.

Management

Intravenous fluids being given

Early recognition and focused management may improve the outcomes in

sepsis. Current professional recommendations include a number of actions

("bundles") to be followed as soon as possible after diagnosis. Within

the first three hours someone with sepsis should have received

antibiotics and, intravenous fluids if there is evidence of either low

blood pressure or other evidence for inadequate blood supply to organs

(as evidenced by a raised level of lactate); blood cultures also should

be obtained within this time period. After six hours the blood pressure

should be adequate, close monitoring of blood pressure and blood supply

to organs should be in place, and the lactate should be measured again

if initially it was raised. A related bundle, the "Sepsis Six", is in widespread use in the United Kingdom;

this requires the administration of antibiotics within an hour of

recognition, blood cultures, lactate and hemoglobin determination, urine

output monitoring, high-flow oxygen, and intravenous fluids.

Apart from the timely administration of fluids and antibiotics,

the management of sepsis also involves surgical drainage of infected

fluid collections and appropriate support for organ dysfunction. This

may include hemodialysis in kidney failure, mechanical ventilation in lung dysfunction, transfusion of blood products, and drug and fluid therapy for circulatory failure. Ensuring adequate nutrition—preferably by enteral feeding, but if necessary, by parenteral nutrition—is important during prolonged illness. Medication to prevent deep vein thrombosis and gastric ulcers also may be used.

Antibiotics

Two

sets of blood cultures (aerobic and anaerobic) are recommended without

delaying the initiation of antibiotics. Cultures from other sites such

as respiratory secretions, urine, wounds, cerebrospinal fluid, and

catheter insertion sites (in-situ more than 48 hours) are recommended if

infections from these sites are suspected. In severe sepsis and septic shock, broad-spectrum antibiotics (usually two, a β-lactam antibiotic with broad coverage, or broad-spectrum carbapenem

combined with fluoroquinolones, macrolides, or aminoglycosides) are

recommended. However, combination of antibiotics is not recommended for

the treatment of sepsis but without shock and immunocompromised persons

unless the combination is used to broaden the anti-bacterial activity.

The choice of antibiotics is important in determining the survival of

the person.

Some recommend they be given within one hour of making the diagnosis,

stating that for every hour of delay in the administration of

antibiotics, there is an associated 6% rise in mortality. Others did not find a benefit with early administration.

Several factors determine the most appropriate choice for the

initial antibiotic regimen. These factors include local patterns of

bacterial sensitivity to antibiotics, whether the infection is thought

to be a hospital or community-acquired infection, and which organ systems are thought to be infected.

Antibiotic regimens should be reassessed daily and narrowed if

appropriate. Treatment duration is typically 7–10 days with the type of

antibiotic used directed by the results of cultures. If the culture

result is negative, antibiotics should be de-escalated according to

person's clinical response or stopped altogether if infection is not

present to decrease the chances that the person is infected with multiple drug resistance organisms. In case of people having high risk of being infected with multiple drug resistance organisms such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, addition of antibiotic specific to gram-negative organism is recommended. For Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin or teicoplanin is recommended. For Legionella infection, addition of macrolide or fluoroquinolone is chosen. If fungal infection is suspected, an echinocandin, such as caspofungin or micafungin, is chosen for people with severe sepsis, followed by triazole (fluconazole and itraconazole) for less ill people. Prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended in people who has SIRS without any infectious origin such as acute pancreatitis and burns unless sepsis is suspected.

Once daily dosing of aminoglycoside

is sufficient to achieve peak plasma concentration for clinical

response without kidney toxicity. Meanwhile, for antibiotics with low

volume distribution (vancomycin, teicoplanin, colistin), loading dose is

required to achieve adequate therapeutic level to fight infections.

Frequent infusions of beta-lactam antibiotics without exceeding total

daily dose would help to keep the antibiotics level above minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), thus providing better clinical response. Giving beta-lactam antibiotics continuously may be better than giving them intermittently. Access to therapeutic drug monitoring is important to ensure adequate drug therapeutic level while at the same time preventing the drug from reaching toxic level.

Intravenous fluids

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign

has recommended 30 ml/kg of fluid to be given in adults in the first

three hours followed by fluid titration according to blood pressure,

urine output, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation with a target mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 65 mmHg. In children an initial amount of 20ml/kg is reasonable in shock. In cases of severe sepsis and septic shock where a central venous catheter is used to measure blood pressures dynamically, fluids should be administered until the central venous pressure (CVP) reaches 8–12 mmHg. Once these goals are met, the central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2), i.e., the oxygen saturation of venous blood as it returns to the heart as measured at the vena cava, is optimized. If the ScvO2 is less than 70%, blood may be given to reach a hemoglobin of 10 g/dL and then inotropes are added until the ScvO2 is optimized. In those with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and sufficient tissue blood fluid, more fluids should be given carefully.

Crystalloid is recommended as the fluid of choice for resuscitation. Albumin can be used if large amount of crystalloid is required for resuscitaition. Crystalloid solutions shows little difference with hydroxyethyl starch in terms of risk of death. Starches also carry an increased risk of acute kidney injury, and need for blood transfusion. Various colloid solutions (such as modified gelatin) carry no advantage over crystalloid. Albumin also appears to be of no benefit over crystalloids.

Blood products

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign recommended packed red blood cells transfusion for hemoglobin levels below 70 g/L if there is no myocardial ischemia, hypoxemia, or acute bleeding.

In a 2014 trial, blood transfusions to keep target hemoglobin above 70

or 90 g/L did not make any difference to survival rates; meanwhile,

those with a lower threshold of transfusion received fewer transfusions

in total. Erythropoietin is not recommended in the treatment of anemia with septic shock because it may precipitate blood clotting events. Fresh frozen plasma

transfusion usually does not correct the underlying clotting

abnormalities before a planned surgical procedure. However, platelet

transfusion is suggested for platelet counts below (10 × 109/L) without any risk of bleeding, or (20 × 109/L) with high risk of bleeding, or (50 × 109/L) with active bleeding, before a planned surgery or an invasive procedure. IV immunoglobulin is not recommended because its beneficial effects are uncertain. Monoclonal and polyclonal preparations of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) do not lower the rate of death in newborns and adults with sepsis. Evidence for the use of IgM-enriched polyclonal preparations of IVIG is inconsistent. On the other hand, the use of antithrombin to treat disseminated intravascular coagulation is also not useful. Meanwhile, the blood purification technique (such as hemoperfusion,

plasma filtration, and coupled plasma filtration adsorption) to remove

inflammatory mediators and bacterial toxins from the blood also does not

demonstrate any survival benefit for septic shock.

Vasopressors

If the person has been sufficiently fluid resuscitated but the mean arterial pressure is not greater than 65 mmHg, vasopressors are recommended. Norepinephrine (noradrenaline) is recommended as the initial choice.

Norepinephrine is often used as a first-line treatment for

hypotensive septic shock because evidence shows that there is a relative

deficiency of vasopressin, when shock continues for 24 to 48 hours. Norepinephrine raises blood pressure through a vasoconstriction effect, with little effect on stroke volume and heart rate.

In some people, the required dose of vasopressor needed to increase the

mean arterial pressure can become exceedingly high that it becomes

toxic. In order to reduce the required dose of vasopressor, epinephrine may be added.

Epinephrine is not often used as a first-line treatment for hypotensive

shock because it reduces blood flow to the abdominal organs and

increases lactate levels.

However, one of the adrenaline side effects is that it reduces blood

flow to abdominal organs and may cause increased lactate levels.

Vasopressin can be used in septic shock because studies have shown that

there is a relative deficiency of vasopressin when shock continues for

24 to 48 hours. However, vasopressin reduces blood flow to the heart,

finger/toes, and abdominal organs, resulting in a lack of oxygen supply

to these tissues. Dopamine is typically not recommended. Although dopamine is useful to increase the stroke volume of the heart, it causes more abnormal heart rhythms

than norepinephrine and also has an immunosuppressive effect. Dopamine

is not proven to have protective properties on the kidneys. Dobutamine can also be used in hypotensive septic shock to increase cardiac output and correct blood flow to the tissues. Dobutamine is not used as often as epinephrine due to its associate side effects, which include reducing blood flow to the gut. Additionally, dobutamine increases the cardiac output by abnormally increasing the heart rate.

Steroids

The use of steroids in sepsis is controversial. Studies do not give a clear picture as to whether and when glucocorticoids should be used. The 2016 Surviving Sepsis Campaign recommends low dose hydrocortisone only if both intravenous fluids and vasopressors are not able to adequately treat septic shock. A 2015 Cochrane review found low-quality evidence of benefit, as did two 2019 reviews.

During critical illness, a state of adrenal insufficiency and tissue resistance to corticosteroids may occur. This has been termed critical illness–related corticosteroid insufficiency. Treatment with corticosteroids might be most beneficial in those with septic shock and early severe ARDS, whereas its role in others such as those with pancreatitis or severe pneumonia is unclear.

However, the exact way of determining corticosteroid insufficiency

remains problematic. It should be suspected in those poorly responding

to resuscitation with fluids and vasopressors. Neither ACTH stimulation testing nor random cortisol levels are recommended to confirm the diagnosis.

The method of stopping glucocorticoid drugs is variable, and it is

unclear whether they should be slowly decreased or simply abruptly

stopped. However, the 2016 Surviving Sepsis Campaign recommended to

taper steroids when vasopressors are no longer needed.

Anesthesia

A target tidal volume of 6 mL/kg of predicted body weight (PBW) and a plateau pressure less than 30 cm H2O is recommended for those who require ventilation due to sepsis-induced severe ARDS. High positive end expiratory pressure

(PEEP) is recommended for moderate to severe ARDS in sepsis as it opens

more lung units for oxygen exchange. Predicted body weight is

calculated based on sex and height, and tools for this are available.

Recruitment maneuvers may be necessary for severe ARDS by briefly

raising the transpulmonary pressure. It is recommended that the head of

the bed be raised if possible to improve ventilation. However, β2 adrenergic receptor agonists are not recommended to treat ARDS because it may reduce survival rates and precipitate abnormal heart rhythms. A spontaneous breathing trial using continuous positive airway pressure

(CPAP), T piece, or inspiratory pressure augmentation can be helpful in

reducing the duration of ventilation. Minimizing intermittent or

continuous sedation is helpful in reducing the duration of mechanical

ventilation.

General anesthesia is recommended for people with sepsis who

require surgical procedures to remove the infective source. Usually

inhalational and intravenous anesthetics are used. Requirements for

anesthetics may be reduced in sepsis. Inhalational anesthetics can reduce the level of proinflammatory cytokines, altering leukocyte adhesion and proliferation, inducing apoptosis (cell death) of the lymphocytes, possibly with a toxic effect on mitochondrial function. Although etomidate has a minimal effect on the cardiovascular system, it is often not recommended as a medication to help with intubation in this situation due to concerns it may lead to poor adrenal function and an increased risk of death. The small amount of evidence there is, however, has not found a change in the risk of death with etomidate.

Paralytic agents are not suggested for use in sepsis cases in the absence of ARDS, as a growing body of evidence points to reduced durations of mechanical ventilation, ICU and hospital stays. However, paralytic use in ARDS

cases remains controversial. When appropriately used, paralytics may

aid successful mechanical ventilation, however evidence has also

suggested that mechanical ventilation in severe sepsis does not improve

oxygen consumption and delivery.

Early goal directed therapy

Early goal directed therapy (EGDT) is an approach to the management of severe sepsis during the initial 6 hours after diagnosis. It is a step-wise approach, with the physiologic goal of optimizing cardiac preload, afterload, and contractility. It includes giving early antibiotics.

EGDT also involves monitoring of hemodynamic parameters and specific

interventions to achieve key resuscitation targets which include

maintaining a central venous pressure between 8–12 mmHg, a mean arterial

pressure of between 65–90 mmHg, a central venous oxygen saturation

(ScvO2) greater than 70% and a urine output of greater than

0.5 ml/kg/hour. The goal is to optimize oxygen delivery to tissues and

achieve a balance between systemic oxygen delivery and demand. An appropriate decrease in serum lactate may be equivalent to ScvO2 and easier to obtain.

In the original trial, early goal directed therapy was found to reduce mortality from 46.5% to 30.5% in those with sepsis, and the Surviving Sepsis Campaign has been recommending its use.

However, three more recent large randomized control trials (ProCESS,

ARISE, and ProMISe), did not demonstrate a 90-day mortality benefit of

early goal directed therapy when compared to standard therapy in severe

sepsis. It is likely that some parts of EGDT are more important than others. Following these trials the use of EGDT is still considered reasonable.

Newborns

Neonatal sepsis can be difficult to diagnose as newborns may be asymptomatic.

If a newborn shows signs and symptoms suggestive of sepsis, antibiotics

are immediately started and are either changed to target a specific

organism identified by diagnostic testing or discontinued after an

infectious cause for the symptoms has been ruled out.

Despite early intervention, death occurs in 13% of children who develop

septic shock, with the risk partly based on other health problems.

Those without multiple organ system failure or who require only one

inotropic agent mortality is low.

Other

Treating

fever in sepsis, including people in septic shock, has not been

associated with any improvement in mortality over a period of 28 days. Treatment of fever still occurs for other reasons.

A 2012 Cochrane review concluded that N-acetylcysteine does not reduce mortality in those with SIRS or sepsis and may even be harmful.

Recombinant activated protein C (drotrecogin alpha) was originally introduced for severe sepsis (as identified by a high APACHE II score), where it was thought to confer a survival benefit. However, subsequent studies showed that it increased adverse events—bleeding risk in particular—and did not decrease mortality. It was removed from sale in 2011. Another medication known as eritoran also has not shown benefit.

In those with high blood sugar levels, insulin to bring it down to 7.8–10 mmol/L (140–180 mg/dL) is recommended with lower levels potentially worsening outcomes.

Glucose levels taken from capillary blood should be interpreted with

care because such measurements may not be accurate. If a person has an

arterial catheter, arterial blood is recommended for blood glucose

testing.

Intermittent or continuous renal replacement therapy may be used if indicated. However, sodium bicarbonate is not recommended for a person with lactic acidosis secondary to hypoperfusion. Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), unfractionated heparin (UFH), and mechanical prophylaxis with intermittent pneumatic compression devices are recommended for any person with sepsis at moderate to high risk of venous thromboembolism. Stress ulcer prevention with proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) and H2 antagonist are useful in a person with risk factors of developing upper gastrointestinal bleeding

(UGIB) such as on mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours,

coagulation disorders, liver disease, and renal replacement therapy. Achieving partial or full enteral feeding (delivery of nutrients through a feeding tube)

is chosen as the best approach to provide nutrition for a person who is

contraindicated for oral intake or unable to tolerate orally in the

first seven days of sepsis when compared to intravenous nutrition. However, omega-3 fatty acids are not recommended as immune supplements for a person with sepsis or septic shock. The usage of prokinetic agents such as metoclopramide, domperidone, and erythromycin

are recommended for those who are septic and unable to tolerate enteral

feeding. However, these agents may precipitate prolongation of the QT interval and consequently provoke a ventricular arrhythmia such as torsades de pointes. The usage of prokinetic agents should be reassessed daily and stopped if no longer indicated.

Prognosis

Severe sepsis will prove fatal in approximately 20–35% of people, and septic shock will prove fatal in 30–70% of people.

Lactate is a useful method of determining prognosis, with those who

have a level greater than 4 mmol/L having a mortality of 40% and those

with a level of less than 2 mmol/L having a mortality of less than 15%.

There are a number of prognostic stratification systems, such as APACHE II

and Mortality in Emergency Department Sepsis. APACHE II factors in the

person's age, underlying condition, and various physiologic variables to

yield estimates of the risk of dying of severe sepsis. Of the

individual covariates, the severity of underlying disease most strongly

influences the risk of death. Septic shock is also a strong predictor of

short- and long-term mortality. Case-fatality rates are similar for

culture-positive and culture-negative severe sepsis. The Mortality in

Emergency Department Sepsis (MEDS) score is simpler, and useful in the

emergency department environment.

Some people may experience severe long-term cognitive decline

following an episode of severe sepsis, but the absence of baseline

neuropsychological data in most people with sepsis makes the incidence

of this difficult to quantify or to study.

Epidemiology

Sepsis causes millions of deaths globally each year and is the most common cause of death in people who have been hospitalized. The number of new cases worldwide of sepsis is estimated to be 18 million cases per year. In the United States sepsis affects approximately 3 in 1,000 people, and severe sepsis contributes to more than 200,000 deaths per year.

Sepsis occurs in 1–2% of all hospitalizations and accounts for as

much as 25% of ICU bed utilization. Due to it rarely being reported as a

primary diagnosis (often being a complication of cancer or other

illness), the incidence, mortality, and morbidity rates of sepsis are

likely underestimated. A study of U.S. states found approximately 651 hospital stays per 100,000 population with a sepsis diagnosis in 2010. It is the second-leading cause of death in non-coronary intensive care unit (ICU) and the tenth-most-common cause of death overall (the first being heart disease). Children under 12 months of age and elderly people have the highest incidence of severe sepsis.

Among people from the U.S. who had multiple sepsis hospital admissions

in 2010, those who were discharged to a skilled nursing facility or

long-term care following the initial hospitalization were more likely to

be readmitted than those discharged to another form of care.

A study of 18 U.S. states found that, amongst people with Medicare in

2011, sepsis was the second most common principal reason for readmission

within 30 days.

Several medical conditions increase a person's susceptibility to

infection and developing sepsis. Common sepsis risk factors include age

(especially the very young and old); conditions that weaken the immune

system such as cancer, diabetes, or the absence of a spleen; and major trauma and burns.

From 1979 to 2000, data from the United States National Hospital

Discharge Survey showed that the incidence of sepsis increased fourfold,

to 240 cases per 100,000 population, with higher incidence in men when

compared to women. During the same time frame, the in-hospital case

fatality rate was reduced from 28% to 18%. However, according to the

nationwide inpatient sample from the United States, the incidence of

severe sepsis increased from 200 per 10,000 population in 2003 to 300

cases in 2007 for population aged more than 18 years. The incidence rate

is particularly high among infants, with the incidence of 500 cases per

100,000 population. Mortality related to sepsis increases with age,

from less than 10% in the age group of 3 to 5 years to 60% by sixth

decade of life. The increase in average age of the population, alongside the presence of more people with chronic diseases or on immunosuppressive medications, and also the increase in the number of invasive procedures being performed, has led to an increased rate of sepsis.

History

Personification of septicaemia, carrying a spray can marked "Poison"

The term "σήψις" (sepsis) was introduced by Hippocrates in the fourth century BC, and it meant the process of decay or decomposition of organic matter. In the eleventh century, Avicenna used the term "blood rot" for diseases linked to severe purulent

process. Though severe systemic toxicity had already been observed, it

was only in the 19th century that the specific term – sepsis – was used

for this condition.

The terms "septicemia", also spelled "septicaemia", and "blood

poisoning" referred to the microorganisms or their toxins in the blood.

The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems

(ICD) version 9, which was in use in the US until 2013, used the term

septicemia with numerous modifiers for different diagnoses, such as

"Streptococcal septicemia". All those diagnoses have been converted to sepsis, again with modifiers, in ICD-10, such as "Sepsis due to streptococcus".

The current terms are dependent on the microorganism that is present: bacteremia if bacteria are present in the blood at abnormal levels and are the causative issue, viremia for viruses, and fungemia for a fungus.

By the end of the 19th century, it was widely believed that microbes produced substances that could injure the mammalian host and that soluble toxins released during infection caused the fever and shock that were commonplace during severe infections. Pfeiffer coined the term endotoxin at the beginning of the 20th century to denote the pyrogenic principle associated with Vibrio cholerae. It was soon realised that endotoxins were expressed by most and perhaps all gram-negative bacteria. The lipopolysaccharide character of enteric endotoxins was elucidated in 1944 by Shear. The molecular character of this material was determined by Luderitz et al. in 1973.

It was discovered in 1965 that a strain of C3H/HeJ mice were immune to the endotoxin-induced shock. The genetic locus for this effect was dubbed Lps. These mice were also found to be hypersusceptible to infection by gram-negative bacteria. These observations were finally linked in 1998 by the discovery of the toll-like receptor gene 4 (TLR 4).

Genetic mapping work, performed over a period of five years, showed

that TLR4 was the sole candidate locus within the Lps critical region;

this strongly implied that a mutation within TLR4 must account for the

lipopolysaccharide resistance phenotype. The defect in the TLR4 gene

that led to the endotoxin resistant phenotype was discovered to be due

to a mutation in the cytoplasm.

Controversy occurred in the scientific community over the use of

mouse models in research into sepsis in 2013, when scientists published a

review of the mouse immune system compared to the human immune system,

and showed that on a systems level, the two worked very differently; the

authors noted that as of the date of their article over 150 clinical

trials of sepsis had been conducted in humans, almost all of them

supported by promising data in mice, and that all of them had failed.

The authors called for abandoning the use of mouse models in sepsis

research; others rejected that but called for more caution in

interpreting the results of mouse studies, and more careful design of

preclinical studies. One approach is to rely more on studying biopsies and clinical data from people who have had sepsis, to try to identify biomarkers and drug targets for intervention.

Society and culture

Economics

Sepsis

was the most expensive condition treated in United States' hospital

stays in 2013, at an aggregate cost of $23.6 billion for nearly 1.3

million hospitalizations. Costs for sepsis hospital stays more than quadrupled since 1997 with an 11.5 percent annual increase.

By payer, it was the most costly condition billed to Medicare and the

uninsured, the second-most costly billed to Medicaid, and the

fourth-most costly billed to private insurance.

Education

A large international collaboration entitled the "Surviving Sepsis Campaign" was established in 2002

to educate people about sepsis and to improve outcomes with sepsis. The

Campaign has published an evidence-based review of management

strategies for severe sepsis, with the aim to publish a complete set of

guidelines in subsequent years.

Sepsis Alliance

is a charitable organization that was created to raise sepsis awareness

among both the general public and healthcare professionals.

Research

Phenotypic strategy switches of microbes capable of provoking sepsis

Some authors suggest that initiating sepsis by the normally mutualistic (or neutral) members of the microbiome may not always be an accidental side effect of the deteriorating host immune system. Rather it is often an adaptive

microbial response to a sudden decline of host survival chances. Under

this scenario, the microbe species provoking sepsis benefit from

monopolizing the future cadaver, utilizing its biomass as decomposers, and then transmitting through soil or water to establish mutualistic relations with new individuals. The bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Proteus spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella spp., Clostridium spp., Lactobacillus spp., Bacteroides spp. and the fungi Candida spp. are all capable of such a high level of phenotypic plasticity. Evidently, not all cases of sepsis arise through such adaptive microbial strategy switches.