Example of an approximately 40,000 probe spotted oligo microarray with enlarged inset to show detail.

Microarray analysis techniques are used in interpreting the data generated from experiments on DNA (Gene chip analysis), RNA, and protein microarrays, which allow researchers to investigate the expression state of a large number of genes - in many cases, an organism's entire genome - in a single experiment.

Such experiments can generate very large amounts of data, allowing

researchers to assess the overall state of a cell or organism. Data in

such large quantities is difficult - if not impossible - to analyze

without the help of computer programs.

Introduction

Microarray

data analysis is the final step in reading and processing data produced

by a microarray chip. Samples undergo various processes including

purification and scanning using the microchip, which then produces a

large amount of data that requires processing via computer software. It

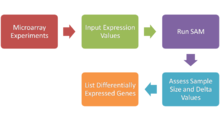

involves several distinct steps, as outlined in the image below.

Changing any one of the steps will change the outcome of the analysis,

so the MAQC Project

was created to identify a set of standard strategies. Companies exist

that use the MAQC protocols to perform a complete analysis.

The steps required in a microarray experiment

Techniques

National Center for Toxicological Research scientist reviews microarray data

Most microarray manufacturers, such as Affymetrix and Agilent,

provide commercial data analysis software alongside their microarray

products. There are also open source options that utilize a variety of

methods for analyzing microarray data.

Aggregation and normalization

Comparing

two different arrays or two different samples hybridized to the same

array generally involves making adjustments for systematic errors

introduced by differences in procedures and dye intensity effects. Dye

normalization for two color arrays is often achieved by local regression. LIMMA provides a set of tools for background correction and scaling, as well as an option to average on-slide duplicate spots. A common method for evaluating how well normalized an array is, is to plot an MA plot of the data. MA plots can be produced using programs and languages such as R, MATLAB, and Excel.

Raw Affy data contains about twenty probes for the same RNA

target. Half of these are "mismatch spots", which do not precisely

match the target sequence. These can theoretically measure the amount of

nonspecific binding for a given target. Robust Multi-array Average

(RMA) is a normalization approach that does not take advantage of these

mismatch spots, but still must summarize the perfect matches through median polish. The median polish algorithm, although robust, behaves differently depending on the number of samples analyzed.

Quantile normalization, also part of RMA, is one sensible approach to

normalize a batch of arrays in order to make further comparisons

meaningful.

The current Affymetrix MAS5 algorithm, which uses both perfect

match and mismatch probes, continues to enjoy popularity and do well in

head to head tests.

Flowchart showing how the MAS5 algorithm by Agilent works.

Factor Analysis for Robust Microarray Summarization (FARMS)

is a model-based technique for summarizing array data at perfect match

probe level. It is based on a factor analysis model for which a Bayesian

maximum a posteriori method optimizes the model parameters under the

assumption of Gaussian measurement noise. According to the Affycomp

benchmark FARMS outperformed all other summarizations methods with respect to sensitivity and specificity.

Identification of significant differential expression

Many

strategies exist to identify array probes that show an unusual level of

over-expression or under-expression. The simplest one is to call

"significant" any probe that differs by an average of at least twofold

between treatment groups. More sophisticated approaches are often

related to t-tests

or other mechanisms that take both effect size and variability into

account. Curiously, the p-values associated with particular genes do

not reproduce well between replicate experiments, and lists generated by

straight fold change perform much better.

This represents an extremely important observation, since the point of

performing experiments has to do with predicting general behavior. The

MAQC group recommends using a fold change assessment plus a

non-stringent p-value cutoff, further pointing out that changes in the

background correction and scaling process have only a minimal impact on

the rank order of fold change differences, but a substantial impact on

p-values.

Clustering

Clustering is a data mining technique used to group genes having similar expression patterns. Hierarchical clustering, and k-means clustering are widely used techniques in microarray analysis.

Hierarchical clustering

Hierarchical clustering is a statistical method for finding relatively homogeneous clusters. Hierarchical clustering consists of two separate phases. Initially, a distance matrix containing all the pairwise distances between the genes is calculated. Pearson’s correlation and Spearman’s correlation are often used as dissimilarity estimates, but other methods, like Manhattan distance or Euclidean distance,

can also be applied. Given the number of distance measures available

and their influence in the clustering algorithm results, several studies

have compared and evaluated different distance measures for the

clustering of microarray data, considering their intrinsic properties

and robustness to noise.

After calculation of the initial distance matrix, the hierarchical

clustering algorithm either (A) joins iteratively the two closest

clusters starting from single data points (agglomerative, bottom-up

approach, which is fairly more commonly used), or (B) partitions

clusters iteratively starting from the complete set (divisive, top-down

approach). After each step, a new distance matrix between the newly

formed clusters and the other clusters is recalculated. Hierarchical

cluster analysis methods include:

- Single linkage (minimum method, nearest neighbor)

- Average linkage (UPGMA).

- Complete linkage (maximum method, furthest neighbor)

Different studies have already shown empirically that the Single

linkage clustering algorithm produces poor results when employed to gene

expression microarray data and thus should be avoided.

K-means clustering

K-means clustering is an algorithm for grouping genes or samples based on pattern into K groups. Grouping is done by minimizing the sum of the squares of distances between the data and the corresponding cluster centroid. Thus the purpose of K-means clustering is to classify data based on similar expression. K-means clustering algorithm and some of its variants (including k-medoids)

have been shown to produce good results for gene expression data (at

least better than hierarchical clustering methods). Empirical

comparisons of k-means, k-medoids, hierarchical methods and, different distance measures can be found in the literature.

Pattern recognition

Commercial systems for gene network analysis such as Ingenuity and Pathway studio

create visual representations of differentially expressed genes based

on current scientific literature. Non-commercial tools such as FunRich, GenMAPP and Moksiskaan

also aid in organizing and visualizing gene network data procured from

one or several microarray experiments. A wide variety of microarray

analysis tools are available through Bioconductor written in the R programming language. The frequently cited SAM module and other microarray tools are available through Stanford University. Another set is available from Harvard and MIT.

Example of FunRich tool output. Image shows the result of comparing 4 different genes.

Specialized software tools for statistical analysis to determine the

extent of over- or under-expression of a gene in a microarray experiment

relative to a reference state have also been developed to aid in

identifying genes or gene sets associated with particular phenotypes. One such method of analysis, known as Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA), uses a Kolmogorov-Smirnov-style statistic to identify groups of genes that are regulated together.

This third-party statistics package offers the user information on the

genes or gene sets of interest, including links to entries in databases

such as NCBI's GenBank and curated databases such as Biocarta and Gene Ontology. Protein complex enrichment analysis tool (COMPLEAT) provides similar enrichment analysis at the level of protein complexes. The tool can identify the dynamic protein complex regulation under different condition or time points. Related system, PAINT and SCOPE performs a statistical analysis on gene promoter regions, identifying over and under representation of previously identified transcription factor

response elements. Another statistical analysis tool is Rank Sum

Statistics for Gene Set Collections (RssGsc), which uses rank sum

probability distribution functions to find gene sets that explain

experimental data.

A further approach is contextual meta-analysis, i.e. finding out how a

gene cluster responds to a variety of experimental contexts. Genevestigator

is a public tool to perform contextual meta-analysis across contexts

such as anatomical parts, stages of development, and response to

diseases, chemicals, stresses, and neoplasms.

Significance analysis of microarrays (SAM)

Significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) is a statistical technique, established in 2001 by Virginia Tusher, Robert Tibshirani and Gilbert Chu, for determining whether changes in gene expression are statistically significant. With the advent of DNA microarrays,

it is now possible to measure the expression of thousands of genes in a

single hybridization experiment. The data generated is considerable,

and a method for sorting out what is significant and what isn't is

essential. SAM is distributed by Stanford University in an R-package.

SAM identifies statistically significant genes by carrying out gene specific t-tests and computes a statistic dj for each gene j, which measures the strength of the relationship between gene expression and a response variable. This analysis uses non-parametric statistics, since the data may not follow a normal distribution. The response variable describes and groups the data based on experimental conditions. In this method, repeated permutations

of the data are used to determine if the expression of any gene is

significant related to the response. The use of permutation-based

analysis accounts for correlations in genes and avoids parametric assumptions about the distribution of individual genes. This is an advantage over other techniques (e.g., ANOVA and Bonferroni), which assume equal variance and/or independence of genes.

Basic protocol

- Perform microarray experiments — DNA microarray with oligo and cDNA primers, SNP arrays, protein arrays, etc.

- Input Expression Analysis in Microsoft Excel — see below

- Run SAM as a Microsoft Excel Add-Ins

- Adjust the Delta tuning parameter to get a significant # of genes along with an acceptable false discovery rate (FDR)) and Assess Sample Size by calculating the mean difference in expression in the SAM Plot Controller

- List Differentially Expressed Genes (Positively and Negatively Expressed Genes)

Running SAM

- SAM is available for download online at http://www-stat.stanford.edu/~tibs/SAM/ for academic and non-academic users after completion of a registration step.

- SAM is run as an Excel Add-In, and the SAM Plot Controller allows Customization of the False Discovery Rate and Delta, while the SAM Plot and SAM Output functionality generate a List of Significant Genes, Delta Table, and Assessment of Sample Sizes

- Permutations are calculated based on the number of samples

- Block Permutations

- Blocks are batches of microarrays; for example for eight samples split into two groups (control and affected) there are 4!=24 permutations for each block and the total number of permutations is (24)(24)= 576. A minimum of 1000 permutations are recommended;

the number of permutations is set by the user when imputing correct values for the data set to run SAM

Response formats

Types:

- Quantitative — real-valued (such as heart rate)

- One class — tests whether the mean gene expression differs from zero

- Two class — two sets of measurements

- Unpaired — measurement units are different in the two groups; e.g. control and treatment groups with samples from different patients

- Paired — same experimental units are measured in the two groups; e.g. samples before and after treatment from the same patients

- Multiclass — more than two groups with each containing different experimental units; generalization of two class unpaired type

- Survival — data of a time until an event (for example death or relapse)

- Time course — each experimental units is measured at more than one time point; experimental units fall into a one or two class design

- Pattern discovery — no explicit response parameter is specified; the user specifies eigengene (principal component) of the expression data and treats it as a quantitative response

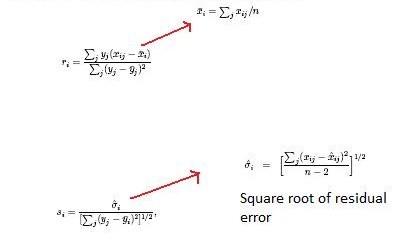

Algorithm

SAM

calculates a test statistic for relative difference in gene expression

based on permutation analysis of expression data and calculates a false

discovery rate. The principal calculations of the program are

illustrated below.

The so constant is chosen to minimize the coefficient of variation of di. ri is equal to the expression levels (x) for gene i under y experimental conditions.

Fold changes (t) are specified to guarantee genes called

significant change at least a pre-specified amount. This means that the

absolute value of the average expression levels of a gene under each of

two conditions must be greater than the fold change (t) to be called

positive and less than the inverse of the fold change (t) to be called

negative.

The SAM algorithm can be stated as:

- Order test statistics according to magnitude

- For each permutation compute the ordered null (unaffected) scores

- Plot the ordered test statistic against the expected null scores

- Call each gene significant if the absolute value of the test statistic for that gene minus the mean test statistic for that gene is greater than a stated threshold

- Estimate the false discovery rate based on expected versus observed values

Output

- Significant gene sets

- Positive gene set — higher expression of most genes in the gene set correlates with higher values of the phenotype y

- Negative gene set — lower expression of most genes in the gene set correlates with higher values of the phenotype y

SAM features

- Data from Oligo or cDNA arrays, SNP array, protein arrays,etc. can be utilized in SAM

- Correlates expression data to clinical parameters

- Correlates expression data with time

- Uses data permutation to estimates False Discovery Rate for multiple testing

- Reports local false discovery rate (the FDR for genes having a similar di as that gene) and miss rates

- Can work with blocked design for when treatments are applied within different batches of arrays

- Can adjust threshold determining number of gene called significant

Error correction and quality control

Quality control

Entire

arrays may have obvious flaws detectable by visual inspection, pairwise

comparisons to arrays in the same experimental group, or by analysis of

RNA degradation. Results may improve by removing these arrays from the analysis entirely.

Background correction

Depending

on the type of array, signal related to nonspecific binding of the

fluorophore can be subtracted to achieve better results. One approach

involves subtracting the average

signal intensity of the area between spots. A variety of tools for

background correction and further analysis are available from TIGR, Agilent (GeneSpring), and Ocimum Bio Solutions (Genowiz).

Spot filtering

Visual

identification of local artifacts, such as printing or washing defects,

may likewise suggest the removal of individual spots. This can take a

substantial amount of time depending on the quality of array

manufacture. In addition, some procedures call for the elimination of

all spots with an expression value below a certain intensity threshold.