Official Romance language

Co-official Romance language

Unofficial Romance language

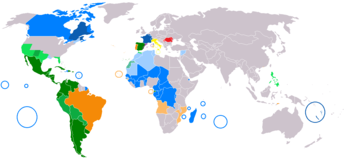

Global distribution of Romance languages:

Blue – French; Green – Spanish; Orange – Portuguese; Yellow – Italian; Red – Romanian

Blue – French; Green – Spanish; Orange – Portuguese; Yellow – Italian; Red – Romanian

The legacy of the Roman Empire has been varied and significant, comparable to that of other hegemonic polities of world history (e.g. Persian Empire, ancient Egypt or imperial China).

The Roman Empire itself, built upon the legacy of other cultures such as Ancient Greece,

has had long-lasting influence with broad geographical reach on a great

range of cultural aspects, including state institutions, law, cultural values, religious beliefs, technological advances, engineering and language.

This legacy survived the demise of the empire itself (5th century AD in the West, and 15th century AD in the East) and went on to shape other civilisations, a process which continues to this day. The city of Rome was the civitas (reflected in the etymology of the word "civilisation") and connected with the actual western civilisation on which subsequent cultures built.

One main legacy is the Latin language of ancient Rome, epitomized by the Classical Latin used in Latin literature, evolved during the Middle Ages and remains in use in the Roman Catholic Church as Ecclesiastical Latin. Vulgar Latin, the common tongue used for regular social interactions, evolved simultaneously into the various Romance languages that exist today (notably Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Romanian, etc.). Although the Western Roman Empire fell in the 5th century AD, the Eastern Roman Empire continued until its conquest by the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century AD and cemented the Greek language in many parts of the Eastern Mediterranean even after the Early Muslim conquests of the 7th century AD. Although there has been a small modern revival of the Hellenistic religion with Hellenism, ancient Roman paganism was largely displaced by Roman Catholic Christianity after the 4th century AD and the Christian conversion of Roman emperor Constantine I (r. 306-337 AD). The Christian faith of the late Roman Empire continued to evolve during the Middle Ages and remains a major facet of the religion and the psyche of the modern Western world.

Ancient Roman architecture, largely indebted to ancient Greek architecture of the Hellenistic period, has influenced the architecture of the Western world, particularly during the Italian Renaissance of the 15th century. Roman law and republican politics (from the age of the Roman Republic) have left an enduring legacy, influencing the Italian city-state republics of the Medieval period as well as the early United States and other modern democratic republics. The Julian calendar of ancient Rome formed the basis of the standard modern Gregorian calendar, while Roman inventions and engineering, such as the construction of concrete domes, continued to influence various peoples after the fall of Rome. Roman models of colonialism and of warfare also became influential.

Language

Latin was the lingua franca of the early Roman Empire and later the Western Roman Empire, while particularly in the East indigenous languages such as Greek and to a lesser degree Egyptian and Aramaic language

continued to be in use. Despite the decline of the Western Roman

Empire, the Latin language continued to flourish in the very different

social and economic environment of the Middle Ages, not least because it became the official language of the Roman Catholic Church. Koine Greek, which served as a lingua franca in the Eastern Empire, is still used today as a sacred language in some Eastern Orthodox churches.

In Western and Central Europe and parts of Africa, Latin retained its elevated status as the main vehicle of communication for the learned classes throughout the Middle Ages; this is especially seen during the Renaissance and Baroque periods. Books which had a revolutionary impact on science, such as Nicolaus Copernicus' De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

(1543), were composed in Latin. This language was not supplanted for

scientific purposes until the 18th century, and for formal descriptions

in zoology, as well as botany - it survived to the later 20th century. The modern international Binomial nomenclature holds to this day: the scientific name of each species is classified by a Latin or Latinized name.

Today the Romance languages, which comprise all languages that descended from Latin,

are spoken by more than 920 million people as their mother tongue, and

300 million people as a second language, mainly in the Americas, Europe,

and Africa. Romance languages are either official, co-official, or significantly used in 72 countries around the world. Of the United Nations's six official languages, two, French and Spanish, descend from Latin.

Additionally, Latin had a great influence on both the grammar and the lexicon of West Germanic languages. Romance words make respectively 59%, 20% and 14% of English, German and Dutch vocabularies.

Those figures can rise dramatically when only non-compound and

non-derived words are included. Accordingly, Romance words make roughly

35% of the vocabulary of Dutch.

Script

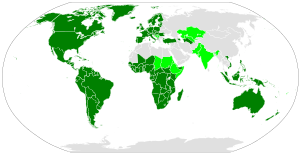

Global distribution of the Latin script.

All three official scripts of the modern European Union—Latin, Greek and Cyrillic—descend from writing systems used in the Roman Empire. Today, the Latin script, the Latin alphabet

spread by the Roman Empire to most of Europe, and derived from the

Phoenician alphabet through an ancient form of the Greek alphabet

adopted and modified by Etruscan, is the most widespread and commonly

used script in the world. Spread by various colonies, trade routes, and

political powers, the script has continued to grow in influence. The

Greek alphabet, which had been popularized throughout the eastern

Mediterranean region during the Hellenistic period, remained the primary script of the Eastern Empire through the Byzantine Empire until its demise in the 15th century.

Latin literature

15th-century printed books by language. The high prestige of Latin still dominated the European discourse a millennium after the demise of the Western Roman Empire.

The Carolingian Renaissance

of the 8th century rescued many works in Latin from oblivion:

manuscripts transcribed at that time are our only sources for works that

later fell into obscurity once more, only to be recovered during the Renaissance: Tacitus, Lucretius, Propertius and Catullus are examples. Other Latin writers were always read: Virgil was reinterpreted as a prophet of Christianity by the 4th century, and gained the reputation of a sorcerer in the 12th century.

Cicero, in a limited number of his works, remained a model of good style, mined for quotations. Ovid was read with a Christian allegorical interpretation. Seneca was reimagined as the correspondent of Saint Paul. Lucan, Persius, Juvenal, Horace, Terence, and Statius survived in the continuing canon and historians Valerius Maximus and Livy continued to be read for the moral lessons history was expected to impart.

Through the Roman Empire, Greek literature also continued to make

an impact in Europe long after the Empire's fall, especially after the

recovery of Greek texts from the East during the high Middle Ages and

the resurgence of Greek literacy during the Renaissance. Plutarch's Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans,

for instance, originally written in Greek, was widely read by educated

Westerners from the Renaissance up to the 20th century. Shakespeare's

play Julius Caesar takes most of its material from Plutarch's biographies of Caesar, Cato, and Brutus, whose exploits were frequently discussed and debated by the literati of the time.

Education

Martianus Capella

developed the system of the seven liberal arts that structured medieval

education. Although the liberal arts were already known in Ancient Greece, it was only after Martianus that the seven liberal arts took on canonical form.

His single encyclopedic work, De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii

"On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury", laid the standard formula of

academic learning from the Christianized Roman Empire of the 5th

century until the Renaissance of the 12th century.

The seven liberal arts were formed by the trivium,

which included the skills of grammar, logic, and rhetoric, while

arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy played part as the quadrivium.

Calendar and measurement

The modern Western calendar is a refinement of the Julian calendar, which was introduced by Julius Caesar. The calendar of the Roman Empire began with the months Ianuarius (January), Februarius (February), and Martius

(March). The common tradition to begin the year on 1 January was a

convention established in ancient Rome. Throughout the medieval period,

the year began on 25 March, the Catholic Solemnity of the Annunciation.

Roman monk of the 5th-century, Dionysius Exiguus, devised the modern dating system of the Anno Domini (AD) era, which is based on the reckoned year of the birth of Jesus, with AD counting years from the start of this epoch, and BC denoting years before the start of the era.

The modern seven-day week follows the Greco-Roman system of planetary hours, in which one of the seven heavenly bodies of the Solar System that were known in ancient times—Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, the Sun, Venus, Mercury and the Moon—is

given "rulership" over each day. The Romance languages (with the

exception of Portuguese, that assigns an ordinal number to five days of

the week, from Monday to Friday, beginning with segunda-feira, and ending with sexta-feira) preserve the original Latin names of each day of the week, except for Sunday, which came to be called dies dominicus (Lord's Day) under Christianity.

This system for the days of the week spread to Celtic and

Germanic peoples, as well as the Albanians, before the collapse of the

empire, after which the names of comparable gods were substituted for

the Roman deities in some languages. In Germanic languages, for

instance, Thor stood in for Jupiter (Jove), yielding "Thursday" from the Latin dies Iovis, while in Albanian, native deities En and Prende were assigned to Thursday and Friday respectively.

Hours of the day

The 12-hour clock is a time convention popularized by the Romans in

which the 24 hours of the day are divided into two periods. The Romans

divided the day into 12 equal hours, A.M. (ante-meridiem, meaning before midday) and P.M. (post-meridiem, meaning past midday). The Romans also started the practice used worldwide today of a new day beginning at midnight.

Numerals and units

A typical clock face with Roman numerals in Bad Salzdetfurth, Germany. The notion of a twelve-hour day dates to the Roman Empire.

Roman numerals continued as the primary way of writing numbers in

Europe until the 14th century, when they were largely replaced in common

usage by Hindu-Arabic numerals.

The Roman numeral system continues to be widely used, however, in

certain formal and minor contexts, such as on clock faces, coins, in the

year of construction on cornerstone inscriptions, and in generational suffixes (such as Louis XIV or William Howard Taft IV). According to the Royal Spanish Academy, in the Spanish language centuries must be written in Roman numerals, so "21st century" should be written as "Siglo XXI".

The Romans solidified the modern concept of the hour as one-24th part of a day and night. The English measurement system also retains features of the Ancient Roman foot (11.65 modern inches), which was used in England prior to the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain. The inch itself derives from the Roman uncia, meaning one-twelfth part.

Religion

Christianity by percentage of population in each country.

While classical Roman and Hellenistic religion were ultimately superseded by Christianity, many key theological ideas and questions that are characteristic of Western religions originated with pre-Christian theology. The first cause argument for the existence of God, for instance, originates with Plato. Design arguments, which were introduced by Socrates and Aristotle and remain widely discussed to this day, formed an influential component of Stoic theology well into the late Roman period. The problem of evil was widely discussed among ancient philosophers, including the Roman writers such as Cicero and Seneca, and many of the answers they provided were later absorbed into Christian theodicy. In Christian moral theology, moreover, the field of natural law ethics draws heavily on the tradition established by Aristotle, the Stoics, and especially by Cicero's popular Latin work, De Legibus. Cicero's conception of natural law "found its way to later centuries notably through the writings of Saint Isidore of Seville and the Decretum of Gratian" and influenced the discussion of the topic up through the era of the American Revolution.

Christianity itself also spread through the Roman Empire; since emperor Theodosius I (AD 379-395), the official state church of the Roman Empire was Christianity.

Subsequently, former Roman territories became Christian states which

exported their religion to other parts of the world, through

colonization and missionaries.

Christianity also served as a conduit for preserving and

transmitting Greco-Roman literary culture. Classical educational

tradition in the liberal arts was preserved after the fall of the empire by the medieval Christian university. Education in the Middle Ages relied heavily on Greco-Roman books such as Euclid's Elements and the influential quadrivium textbooks written in Latin by the Roman statesman Boethius (AD 480–524).

Major works of Greek and Latin literature, moreover, were both

read and written by Christians during the imperial era. Many of the most

influential works of the early Christian tradition were written by

Roman and Hellenized theologians who engaged heavily with the literary culture of the empire (see church fathers). St. Augustine's (AD 354-430) City of God, for instance, draws extensively on Virgil, Cicero, Varro, Homer, Plato,

and elements of Roman values and identity to criticize paganism and

advocate for Christianity amidst a crumbling empire. The engagement of

early Christians as both readers and writers of important Roman and

Greek literature helped to ensure that the literary culture of Rome

would persist after the fall of the empire. For thousands of years to

follow, religious scholars in the Latin West from Bede to Thomas Aquinas and later renaissance figures such as Dante, Montaigne and Shakespeare

would continue to read, reference and imitate both Christian and pagan

literature from the Roman Empire. In the east, the empire's prolific

tradition of Greek literature continued uninterrupted after the fall of

the west, in part due to the works of the Greek fathers, who were widely read by Christians in medieval Byzantium and continue to influence religious thought to this day.

Science and philosophy

Ptolemy's refined geocentric theory of epicycles was backed up by rigorous mathematics and detailed astronomical observations. It was not overturned until the Copernican Revolution, over a thousand years later.

While much of the most influential Greek science and philosophy

was developed before the rise of the Empire, major innovations occurred

under Roman rule that have had a lasting impact on the intellectual

world. The traditions of Greek, Egyptian and Babylonian scholarship

continued to flourish at great centers of learning such as Athens, Alexandria, and Pergamon.

Epicurean philosophy reached a literary apex in the long poem by Lucretius, who advocated an atomic theory of matter and revered the older teachings of the Greek Democritus. The works of the philosophers Seneca the Younger, Epictetus and the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius were widely read during the revival of Stoic thought in the Renaissance, which synthesized Stoicism and Christianity. Fighter pilot James Stockdale famously credited the philosophy of Epictetus as being a major source of strength when he was shot down and held as prisoner during the Vietnam War. Plato's philosophy continued to be widely studied under the Empire, growing into the sophisticated neoplatonic system through the influence of Plotinus. Platonic philosophy was largely reconciled with Christianity by the Roman theologian Augustine of Hippo,

who, while a staunch opponent of Roman paganism, viewed the Platonists

as having more in common with Christians than the other pagan schools. To this day, Plato's Republic is considered the foundational work of Western philosophy, and is read by students around the globe.

The widespread Lorem ipsum

text, which is widely used as a meaningless placeholder in modern

typography and graphic design, is derived from the Latin text of

Cicero's philosophical treatise De finibus.

Pagan philosophy was gradually supplanted by Christianity in the later years of the Empire, culminating in the closure of the Academy of Athens by Justinian I.

Many Greek-speaking philosophers moved to the east, outside the

borders of the Empire. Neoplatonism and Aristotelianism gained a

stronghold in Persia, where they were a heavy influence on early Islamic philosophy. Thinkers of the Islamic Golden Age such as Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and Ibn Rushd (Averroës)

engaged deeply with Greek philosophy, and played a major role in saving

works of Aristotle that had been lost to the Latin West. The influence

of Greek philosophy on Islam was dramatically reduced In the 11th

century when the views of Avicenna and Avveroes were strongly criticized

by Al-Ghazali. His Incoherence of the Philosophers is among the most influential books in Islamic history. In Western Europe, meanwhile, the recovery of Greek texts during the Scholastic period had a profound influence on Latin science and theology from the Middle Ages into the Renaissance.

In science, the theories of the Greco-Roman physician Galen dominated Western medical thought and practice for more than 1,300 years. Ptolemy produced the most thorough and sophisticated astronomical theory of antiquity, documented in the Almagest. The Ptolemaic model

of the solar system would remain the dominant approach to astronomy

across Europe and the Middle East for more than a thousand years. Forty

eight of the 88 constellations the IAU recognizes today were recorded in the seventh and eighth books of Claudius Ptolemy's Almagest.

At Alexandria, the engineer and experimentalist Hero of Alexandria founded the study of mechanics and pneumatics. In modern geometry, Heron's formula bears his name. Roman Alexandria also saw the seeds of modern algebra arise in the works of Diophantus.

Greek algebra continued to be studied in the east well after the fall

of the Western Empire, where it matured into modern algebra in the hands

of al-Khwārizmī (see the history of algebra). The study of Diophantine Equations and Diophantine Approximations are still important areas of mathematical research today.

Roman law and politics

Roman Law in blue tones.

Republics

Presidential republics with a full presidential system.

Presidential republics with a semi-presidential system.

Parliamentary republics with a ceremonial president, where the prime minister is the executive.

One-party state considered Republics

Although the law of the Roman Empire is not used today, modern law in

many jurisdictions is based on principles of law used and developed

during the Roman Empire. Some of the same Latin terminology

is still used today. The general structure of jurisprudence used today,

in many jurisdictions, is the same (trial with a judge, plaintiff, and

defendant) as that established during the Roman Empire.

The modern concept of republican government is directly modeled on the Roman Republic. The republican institutions of Rome survived in many of the Italian city-states of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The United States Congress is inspired by the Roman senate and legislative assemblies, while the president holds a position similar to that of a Roman consul. Many European political thinkers of the Enlightenment were avid consumers of Latin literature. Montesquieu, Edmund Burke, and John Adams were all strongly influenced by Cicero,

for instance. Adams recommended Cicero as a model for politicians to

imitate, and once remarked that "the sweetness and grandeur of his

sounds, and the harmony of his numbers give pleasure enough to reward

the reading if one understood none of his meaning."

Inventions

Gnocchi, a kind of traditional Italian pasta, was introduced to various parts of Europe by the Roman legions during the expansion of the empire.

Many Roman inventions were improved versions of other people's

inventions and ranged from military organization, weapon improvements, armour, siege technology, naval innovation, architecture, medical instruments, irrigation, civil planning, construction, agriculture and many more areas of civic, governmental, military and engineering development.

That said, the Romans also developed a huge array of new

technologies and innovations. Many came from common themes but were

vastly superior to what had come before, whilst others were totally new

inventions developed by and for the needs of Empire and the Roman way of

life.

Some of the more famous examples are the Roman aqueducts (some of which are still in use today), Roman roads, water powered milling machines, thermal heating systems (as employed in Roman baths, and also used in palaces and wealthy homes) sewage and pipe systems and the invention and widespread use of concrete.

Metallurgy and glass work (including the first widespread use of

glass windows) and a wealth of architectural innovations including high

rise buildings, dome construction, bridgeworks and floor construction

(seen in the functionality of the Colosseum's arena and the underlying rooms/areas beneath it) are other examples of Roman innovation and genius.

Military inventiveness was widespread and ranged from

tactical/strategic innovations, new methodologies in training,

discipline and field medicine as well as inventions in all aspects of

weaponry, from armor and shielding to siege engines and missile

technology.

This combination of new methodologies, technical innovation, and

creative invention in the military gave Rome the edge against its

adversaries for half a millennium, and with it, the ability to create an

empire that even today, more than 2000 years later, continues to leave

its legacy in many areas of modern life.

Colonies and roads

Rome left a legacy of founding many cities as Colonia.

There were more than 500 Roman colonies spread through the Empire, most

of them populated by veterans of the Roman legions. Some Roman colonies

rose to become influential commercial and trade centers, transportation

hubs and capitals of international empires, like Constantinople, London, Paris and Vienna.

All those colonies were connected by another important legacy of the Roman Empire: the Roman roads.

Indeed, the empire comprised more than 400,000 kilometres (250,000 mi)

of roads, of which over 80,500 kilometres (50,000 mi) were stone-paved.

The courses (and sometimes the surfaces) of many Roman roads survived

for millennia and many are overlaid by modern roads, like the Via Emilia

in northern Italy. The roads are closely linked to modern-day

economies, with those that survived from the empire's territorial peak

in 117CE having more economic activity today. This is especially true in

European areas, which kept wheeled vehicles in the latter half of the

first millennium, whereas other regions preferred cheaper methods of

transport such as camel caravans.

Architecture

The Cathedral of Vilnius (1783), by Laurynas Gucevičius.

In the mid-18th century, Roman architecture inspired neoclassical architecture. Neoclassicism was an international movement. Though neoclassical architecture employs the same classical vocabulary as late Baroque architecture, it tends to emphasize its planar qualities, rather than sculptural volumes. Projections and recessions and their effects of light, and shade

are flatters; sculptural bas-reliefs are flatter and tend to be

enframed in friezes, tablets or panels. Its clearly articulated

individual features are isolated rather than interpenetrating,

autonomous and complete in themselves.

International neoclassical architecture was exemplified in Karl Friedrich Schinkel's buildings, especially the Old Museum in Berlin, Sir John Soane's Bank of England in London and the newly built White House and Capitol in Washington, DC in the United States. The Scots architect Charles Cameron created palatial Italianate interiors for the German-born Catherine II the Great in St. Petersburg.

Italy clung to Rococo until the Napoleonic regimes brought the

new archaeological classicism, which was embraced as a political

statement by young, progressive, urban Italians with republican

leanings.

Imperial idea

Coat of arms of the Palaiologoi, the last imperial dynasty of the Eastern Roman Empire.

From a legal point of view the Roman Empire, founded by Augustus in 27 BC and divided into two "parts" (or rather, courts, as the empire continued to be considered as one) after the death of Theodosius I in 395, had survived only in the eastern part which, with the deposition of the last western emperor Romulus Augustulus, in 476, had also obtained the imperial regalia of the western part reuniting from a formal point of view the Roman Empire.

The Roman line continued uninterrupted to rule the Eastern Roman Empire, whose main characteristics were Roman concept of state, medieval Greek culture and language, and Orthodox Christian faith. The Byzantines themselves never ceased to refer to themselves as "Romans" (Rhomaioi)

and to their state as the "Roman Empire", the "Empire of the Romans"

(in Greek Βασιλεία των Ῥωμαίων, Basileía ton Rhōmaíōn) or "Romania"

(Ῥωμανία, Rhōmanía). Likewise, they were called "Rûm" (Rome) by their eastern enemies to the point that competing neighbours even acquired its name, such as the Sultanate of Rûm.

Flask for Priming Power with the Justice of Trajan (mid-16th century), depicting a woman's plea for justice from Trajan, with an imperial pennant of the Habsburgs suggesting that as Holy Roman Emperors they are the political descendants of the ancient Roman emperors (Walters Art Museum)

The designation of the Empire as "Byzantine" is a retrospective idea: it began only in 1557, a century after the fall of Constantinople, when German historian Hieronymus Wolf published his work Corpus Historiæ Byzantinæ, a collection of Byzantine sources. The term did not come in general use in the Western world before the 19th century, when modern Greece was born. The end of the continuous tradition of the Roman Empire is open to debate: the final point was the capture of Constantinople in 1453 AD, while some place it at the sack of Constantinople by the crusaders in 1204.

After the fall of Constantinople, Thomas Palaiologos, brother of the last Eastern Roman Emperor, Constantine XI,

was elected emperor and tried to organize the remaining forces. His

rule came to an end after the fall of the last major Byzantine city,

Corinth. He then moved to Italy and continued to be recognized as

Eastern emperor by the Christian powers.

His son Andreas Palaiologos continued claims on the Byzantine throne until he sold the title to Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile before his death in 1502.

However, there is no evidence that any Spanish monarch used the

Byzantine imperial titles, which would have symbolically converted the king of Spain into a legitimate Emperor of Rome.

In Western Europe, the Roman concept of state was continued for almost a millennium by the Holy Roman Empire whose emperors, mostly of German tongue, viewed themselves as the legitimate successors to the ancient imperial tradition (King of the Romans) and Rome as the capital of its Empire. The German title of "Kaiser" is derived from the Latin name Caesar, which is pronounced [ˈkae̯sar] in Classical Latin.

The coronation of Charlemagne as "Roman" emperor by Pope Leo III

in the year 800 was a deprived act of legitimate juridical profile:

only the Roman emperor of the East (called "Byzantine" later by the

Enlightenment in the eighteenth century) would be crowned a peer of him

in the western part, which is why Constantinople was always suspicious

of that act.

The emperors of the Holy Roman Empire sought in many ways to make

themselves accepted by the Byzantines as their peers: with diplomatic

relations, political marriages or threats. Sometimes, however, they did

not obtain the expected results, because from Constantinople they were

always called "King of the Germans", never "Emperor." The Holy Roman

Empire was dissolved in 1806 owing to pressure by Napoleon I.

In Eastern Europe, firstly the Bulgarian, then the Serbian and ultimately the Russian czars (Czar derived from Caesar) proclaimed being Emperors. In Moscow in Russia adopted the idea of being a Third Rome (with Constantinople being the second). Sentiments of being the heir of the fallen Eastern Roman Empire began during the reign of Ivan III, Grand Duke of Moscow who had married Sophia Paleologue, the niece of Constantine XI

(it is important to note that she was not the heiress of the Byzantine

throne, rather her brother Andreas was). Being the most powerful Orthodox Christian state, the Tsars were thought of in Russia as succeeding the Eastern Roman Empire as the rightful rulers of the Orthodox Christian world. There were also competing Bulgarian, Wallachian and Ottoman claims for legal succession of the Roman Empire, Mehmet II "the Conqueror" claiming the title Kayser-i Rûm, meaning Caesar of Rome.

In the early 20th century, the Italian fascists under their "Duce" Benito Mussolini dreamed of a new Roman Empire as an Italian one, encompassing the Mediterranean basin. Associated with Italian fascism also Nazi Germany and Francoist Spain connected their claims with Roman imperialism.