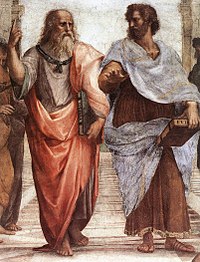

In philosophy, potentiality and actuality are a pair of closely connected principles which Aristotle used to analyze motion, causality, ethics, and physiology in his Physics, Metaphysics, Nicomachean Ethics and De Anima, which is about the human psyche.

The concept of potentiality, in this context, generally refers to any "possibility" that a thing can be said to have. Aristotle did not consider all possibilities the same, and emphasized the importance of those that become real of their own accord when conditions are right and nothing stops them. Actuality, in contrast to potentiality, is the motion, change or activity that represents an exercise or fulfillment of a possibility, when a possibility becomes real in the fullest sense.

These concepts, in modified forms, remained very important into the Middle Ages, influencing the development of medieval theology in several ways. Going further into modern times, while the understanding of nature, and according to some interpretations deity, implied by the dichotomy lost importance, the terminology has found new uses, developing indirectly from the old. This is most obvious in words like "energy" and "dynamic" - words first used in modern physics by the German scientist and philosopher, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Another example is the highly controversial biological concept of an "entelechy".

Potentiality

Potentiality and potency are translations of the Ancient Greek word dunamis (δύναμις) as it is used by Aristotle as a concept contrasting with actuality. Its Latin translation is "potentia", root of the English word potential, and used by some scholars instead of the Greek or English variants.

Dunamis is an ordinary Greek word for possibility or

capability. Depending on context, it could be translated "potency",

"potential", "capacity", "ability", "power", "capability", "strength",

"possibility", "force" and is the root of modern English words "dynamic", "dynamite", and "dynamo". In early modern philosophy, English authors like Hobbes and Locke used the English word "power" as their translation of Latin potentia.

In his philosophy, Aristotle distinguished two meanings of the word dunamis. According to his understanding of nature

there was both a weak sense of potential, meaning simply that something

"might chance to happen or not to happen", and a stronger sense, to

indicate how something could be done well. For example,

"sometimes we say that those who can merely take a walk, or speak,

without doing it as well as they intended, cannot speak or walk". This

stronger sense is mainly said of the potentials of living things,

although it is also sometimes used for things like musical instruments.

Throughout his works, Aristotle clearly distinguishes things that

are stable or persistent, with their own strong natural tendency to a

specific type of change, from things that appear to occur by chance. He

treats these as having a different and more real existence. "Natures

which persist" are said by him to be one of the causes of all things,

while natures that do not persist, "might often be slandered as not

being at all by one who fixes his thinking sternly upon it as upon a

criminal". The potencies which persist in a particular material are one

way of describing "the nature itself" of that material, an innate source

of motion and rest within that material. In terms of Aristotle's theory

of four causes,

a material's non-accidental potential, is the material cause of the

things that can come to be from that material, and one part of how we

can understand the substance (ousia,

sometimes translated as "thinghood") of any separate thing. (As

emphasized by Aristotle, this requires his distinction between accidental causes and natural causes.)

According to Aristotle, when we refer to the nature of a thing, we are

referring to the form, shape or look of a thing, which was already

present as a potential, an innate tendency to change, in that material

before it achieved that form, but things show what they are more fully,

as a real thing, when they are "fully at work".

Actuality

Actuality is often used to translate both energeia (ενέργεια) and entelecheia (ἐντελέχεια) (sometimes rendered in English as "entelechy"). "Actuality" comes from Latin actualitas and is a traditional translation, but its normal meaning in Latin is "anything which is currently happening".

The two words energeia and entelecheia were coined by Aristotle, and he stated that their meanings were intended to converge. In practice, most commentators and translators consider the two words to be interchangeable.

They both refer to something being in its own type of action or at

work, as all things are when they are real in the fullest sense, and not

just potentially real. For example, "to be a rock is to strain to be at

the center of the universe, and thus to be in motion unless constrained

otherwise".

Energeia

Energeia is a word based upon ἔργον (ergon), meaning "work". It is the source of the modern word "energy" but the term has evolved so much over the course of the history of science

that reference to the modern term is not very helpful in understanding

the original as used by Aristotle. It is difficult to translate his use

of energeia into English with consistency. Joe Sachs renders it

with the phrase "being–at–work" and says that "we might construct the

word is-at-work-ness from Anglo-Saxon roots to translate energeia into English". Aristotle says the word can be made clear by looking at examples rather than trying to find a definition.

Two examples of energeiai in Aristotle's works are pleasure and happiness (eudaimonia). Pleasure is an energeia of the human body and mind whereas happiness is more simply the energeia of a human being a human.

Kinesis, translated as movement, motion, or in some contexts change, is also explained by Aristotle as a particular type of energeia. See below.

Entelechy (entelechia)

Entelechy, in Greek entelécheia, was coined by Aristotle and transliterated in Latin as entelechia. According to Sachs (1995, p. 245):

Aristotle invents the word by combining entelēs (ἐντελής, "complete, full-grown") with echein (= hexis, to be a certain way by the continuing effort of holding on in that condition), while at the same time punning on endelecheia (ἐνδελέχεια, "persistence") by inserting "telos" (τέλος, "completion"). This is a three-ring circus of a word, at the heart of everything in Aristotle's thinking, including the definition of motion.

Sachs therefore proposed a complex neologism of his own, "being-at-work-staying-the-same". Another translation in recent years is "being-at-an-end" (which Sachs has also used).

Entelecheia, as can be seen by its derivation, is a kind

of completeness, whereas "the end and completion of any genuine being is

its being-at-work" (energeia). The entelecheia is a continuous being-at-work (energeia)

when something is doing its complete "work". For this reason, the

meanings of the two words converge, and they both depend upon the idea

that every thing's "thinghood" is a kind of work, or in other words a

specific way of being in motion. All things that exist now, and not just

potentially, are beings-at-work, and all of them have a tendency

towards being-at-work in a particular way that would be their proper and

"complete" way.

Sachs explains the convergence of energeia and entelecheia as follows, and uses the word actuality to describe the overlap between them:

Just as energeia extends to entelecheia because it is the activity which makes a thing what it is, entelecheia extends to energeia because it is the end or perfection which has being only in, through, and during activity.

Motion

Aristotle discusses motion (kinēsis) in his Physics quite differently from modern science.

Aristotle's definition of motion is closely connected to his

actuality-potentiality distinction. Taken literally, Aristotle defines

motion as the actuality (entelecheia) of a "potentiality as such".

What Aristotle meant however is the subject of several different

interpretations. A major difficulty comes from the fact that the terms

actuality and potentiality, linked in this definition, are normally

understood within Aristotle as opposed to each other. On the other hand,

the "as such" is important and is explained at length by Aristotle,

giving examples of "potentiality as such". For example, the motion of

building is the energeia of the dunamis of the building materials as building materials

as opposed to anything else they might become, and this potential in

the unbuilt materials is referred to by Aristotle as "the buildable". So

the motion of building is the actualization of "the buildable" and not

the actualization of a house as such, nor the actualization of any other

possibility which the building materials might have had.

| Building materials have different potentials. One is that they can be built with. |

Building is one motion that had been a potential in the building material. So it is the energeia or putting into action, of the building materials as building materials |

A house is built, and no longer moving |

In an influential 1969 paper Aryeh Kosman divided up previous

attempts to explain Aristotle's definition into two types, criticised

them, and then gave his own third interpretation. While this has not

become a consensus, it has been described as having become "orthodox". This and similar more recent publications are the basis of the following summary.

1. The "process" interpretation

Kosman (1969) and Coope (2009) associate this approach with W.D. Ross. Sachs (2005) points out that it was also the interpretation of Averroes and Maimonides.

This interpretation is, to use the words of Ross that "it is the passage to actuality that is kinesis” as opposed to any potentiality being an actuality.

The argument of Ross for this interpretation requires him to assert that Aristotle actually used his own word entelecheia

wrongly, or inconsistently, only within his definition, making it mean

"actualization", which is in conflict with Aristotle's normal use of

words. According to Sachs (2005) this explanation also can not account for the "as such" in Aristotle's definition.

2. The "product" interpretation

Sachs (2005) associates this interpretation with St Thomas of Aquinas

and explains that by this explanation "the apparent contradiction

between potentiality and actuality in Aristotle’s definition of motion"

is resolved "by arguing that in every motion actuality and potentiality

are mixed or blended". Motion is therefore "the actuality of any

potentiality insofar as it is still a potentiality". Or in other words:

The Thomistic blend of actuality and potentiality has the characteristic that, to the extent that it is actual it is not potential and to the extent that it is potential it is not actual; the hotter the water is, the less is it potentially hot, and the cooler it is, the less is it actually, the more potentially, hot.

As with the first interpretation however, Sachs (2005) objects that:

One implication of this interpretation is that whatever happens to be the case right now is an entelechia, as though something that is intrinsically unstable as the instantaneous position of an arrow in flight deserved to be described by the word that everywhere else Aristotle reserves for complex organized states that persist, that hold out against internal and external causes that try to destroy them.

In a more recent paper on this subject, Kosman associates the view of

Aquinas with those of his own critics, David Charles, Jonathan Beere,

and Robert Heineman.

3. The interpretation of Kosman, Coope, Sachs and others

Sachs (2005),

amongst other authors (such as Aryeh Kosman and Ursula Coope), proposes

that the solution to problems interpreting Aristotle's definition must

be found in the distinction Aristotle makes between two different types

of potentiality, with only one of those corresponding to the

"potentiality as such" appearing in the definition of motion. He writes:

The man with sight, but with his eyes closed, differs from the blind man, although neither is seeing. The first man has the capacity to see, which the second man lacks. There are then potentialities as well as actualities in the world. But when the first man opens his eyes, has he lost the capacity to see? Obviously not; while he is seeing, his capacity to see is no longer merely a potentiality, but is a potentiality which has been put to work. The potentiality to see exists sometimes as active or at-work, and sometimes as inactive or latent.

Coming to motion, Sachs gives the example of a man walking across the room and says that...

- "Once he has reached the other side of the room, his potentiality to be there has been actualized in Ross’ sense of the term". This is a type of energeia. However it is not a motion, and not relevant to the definition of motion.

- While a man is walking his potentiality to be on the other side of the room is actual just as a potentiality, or in other words the potential as such is an actuality. "The actuality of the potentiality to be on the other side of the room, as just that potentiality, is neither more nor less than the walking across the room."

Sachs (1995, pp. 78–79), in his commentary of Aristotle's Physics book III gives the following results from his understanding of Aristotle's definition of motion:

The genus of which motion is a species is being-at-work-staying-itself (entelecheia), of which the only other species is thinghood. The being-at-work-staying-itself of a potency (dunamis), as material, is thinghood. The being-at-work-staying-the-same of a potency as a potency is motion.

The importance of actuality in Aristotle's philosophy

The actuality-potentiality distinction in Aristotle is a key element linked to everything in his physics and metaphysics.

Aristotle describes potentiality and actuality, or potency and

action, as one of several distinctions between things that exist or do

not exist. In a sense, a thing that exists potentially does not exist,

but the potential does exist. And this type of distinction is expressed

for several different types of being within Aristotle's categories of

being. For example, from Aristotle's Metaphysics, 1017a:

- We speak of an entity being a "seeing" thing whether it is currently seeing or just able to see.

- We speak of someone having understanding, whether they are using that understanding or not.

- We speak of corn existing in a field even when it is not yet ripe.

- People sometimes speak of a figure being already present in a rock which could be sculpted to represent that figure.

Within the works of Aristotle the terms energeia and entelecheia,

often translated as actuality, differ from what is merely actual

because they specifically presuppose that all things have a proper kind

of activity or work which, if achieved, would be their proper end. Greek

for end in this sense is telos, a component word in entelecheia (a work that is the proper end of a thing) and also teleology. This is an aspect of Aristotle's theory of four causes and specifically of formal cause (eidos, which Aristotle says is energeia) and final cause (telos).

In essence this means that Aristotle did not see things as matter

in motion only, but also proposed that all things have their own aims

or ends. In other words, for Aristotle (unlike modern science) there is a

distinction between things with a natural cause in the strongest sense,

and things that truly happen by accident. He also distinguishes

non-rational from rational potentialities (e.g. the capacity to heat and

the capacity to play the flute, respectively), pointing out that the

latter require desire or deliberate choice for their actualization. Because of this style of reasoning, Aristotle is often referred to as having a teleology, and sometimes as having a theory of forms.

While actuality is linked by Aristotle to his concept of a formal cause, potentiality (or potency) on the other hand, is linked by Aristotle to his concepts of hylomorphic matter and material cause.

Aristotle wrote for example that "matter exists potentially, because it

may attain to the form; but when it exists actually, it is then in the

form".

The active intellect

The active intellect was a concept Aristotle described that requires

an understanding of the actuality-potentiality dichotomy. Aristotle

described this in his De Anima (book 3, ch. 5, 430a10-25) and covered similar ground in his Metaphysics (book 12, ch.7-10). The following is from the De Anima, translated by Joe Sachs,

with some parenthetic notes about the Greek. The passage tries to

explain "how the human intellect passes from its original state, in

which it does not think, to a subsequent state, in which it does." He

inferred that the energeia/dunamis distinction must also exist in the

soul itself:

...since in nature one thing is the material [hulē] for each kind [genos] (this is what is in potency all the particular things of that kind) but it is something else that is the causal and productive thing by which all of them are formed, as is the case with an art in relation to its material, it is necessary in the soul [psuchē] too that these distinct aspects be present;

the one sort is intellect [nous] by becoming all things, the other sort by forming all things, in the way an active condition [hexis] like light too makes the colors that are in potency be at work as colors [to phōs poiei ta dunamei onta chrōmata energeiai chrōmata].

This sort of intellect is separate, as well as being without attributes and unmixed, since it is by its thinghood a being-at-work, for what acts is always distinguished in stature above what is acted upon, as a governing source is above the material it works on.

Knowledge [epistēmē], in its being-at-work, is the same as the thing it knows, and while knowledge in potency comes first in time in any one knower, in the whole of things it does not take precedence even in time.

This does not mean that at one time it thinks but at another time it does not think, but when separated it is just exactly what it is, and this alone is deathless and everlasting (though we have no memory, because this sort of intellect is not acted upon, while the sort that is acted upon is destructible), and without this nothing thinks.

This has been referred to as one of "the most intensely studied sentences in the history of philosophy". In the Metaphysics,

Aristotle wrote at more length on a similar subject and is often

understood to have equated the active intellect with being the "unmoved mover" and God. Nevertheless, as Davidson remarks:

Just what Aristotle meant by potential intellect and active intellect – terms not even explicit in the De anima and at best implied – and just how he understood the interaction between them remains moot to this day. Students of the history of philosophy continue to debate Aristotle's intent, particularly the question whether he considered the active intellect to be an aspect of the human soul or an entity existing independently of man.

Post-Aristotelian usage

New meanings of energeia or energy

Already in Aristotle's own works, the concept of a distinction between energeia and dunamis was used in many ways, for example to describe the way striking metaphors work, or human happiness. Polybius about 150 BC, in his work the Histories uses Aristotle's word energeia in both an Aristotelian way and also to describe the "clarity and vividness" of things. Diodorus Siculus

in 60-30 BC used the term in a very similar way to Polybius. However

Diodorus uses the term to denote qualities unique to individuals. Using

the term in ways that could translated as "vigor" or "energy" (in a more modern sense); for society, "practice" or "custom"; for a thing, "operation" or "working"; like vigor in action.

Platonism and neoplatonism

Already in Plato it is found implicitly the notion of potency and act in his cosmological presentation of becoming (kinēsis) and forces (dunamis), linked to the ordering intellect, mainly in the description of the Demiurge and the "Receptacle" in his Timaeus. It has also been associated to the dyad of Plato's unwritten doctrines, and is involved in the question of being and non-being since from the pre-socratics, as in Heraclitus's mobilism and Parmenides' immobilism. The mythological concept of primordial Chaos is also classically associated with a disordered prime matter (see also prima materia), which, being passive and full of potentialities, would be ordered in actual forms, as can be seen in Neoplatonism, especially in Plutarch, Plotinus, and among the Church Fathers, and the subsequent medieval and Renaissance philosophy, as in Ramon Lllull's Book of Chaos and John Milton's Paradise Lost.

Plotinus was a late classical pagan philosopher and theologian whose monotheistic re-workings of Plato and Aristotle were influential amongst early Christian theologians. In his Enneads he sought to reconcile ideas of Aristotle and Plato together with a form of monotheism,

that used three fundamental metaphysical principles, which were

conceived of in terms consistent with Aristotle's energeia/dunamis

dichotomy, and one interpretation of his concept of the Active Intellect

(discussed above):-

- The Monad or "the One" sometimes also described as "the Good". This is the dunamis or possibility of existence.

- The Intellect, or Intelligence, or, to use the Greek term, Nous, which is described as God, or a Demiurge. It thinks its own contents, which are thoughts, equated to the Platonic ideas or forms (eide). The thinking of this Intellect is the highest activity of life. The actualization of this thinking is the being of the forms. This Intellect is the first principle or foundation of existence. The One is prior to it, but not in the sense that a normal cause is prior to an effect, but instead Intellect is called an emanation of the One. The One is the possibility of this foundation of existence.

- Soul or, to use the Greek term, psyche. The soul is also an energeia: it acts upon or actualizes its own thoughts and creates "a separate, material cosmos that is the living image of the spiritual or noetic Cosmos contained as a unified thought within the Intelligence".

This was based largely upon Plotinus' reading of Plato, but also incorporated many Aristotelian concepts, including the unmoved mover as energeia.

Essence-energies debate in medieval Christian theology

In Eastern Orthodox Christianity, St Gregory Palamas wrote about the "energies" (actualities; singular energeia in Greek, or actus in Latin) of God in contrast to God's "essence" (ousia).

These are two distinct types of existence, with God's energy being the

type of existence which people can perceive, while the essence of God is

outside of normal existence or non-existence or human understanding, i.

e. transcendental, in that it is not caused or created by anything else.

Palamas gave this explanation as part of his defense of the Eastern Orthodox ascetic practice of hesychasm. Palamism became a standard part of Orthodox dogma after 1351.

In contrast, the position of Western Medieval (or Catholic) Christianity, can be found for example in the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas, who relied on Aristotle's concept of entelechy, when he defined God as actus purus, pure act,

actuality unmixed with potentiality. The existence of a truly distinct

essence of God which is not actuality, is not generally accepted in

Catholic Theology.

Influence on modal logic

The

notion of possibility was greatly analyzed by medieval and modern

philosophers. Aristotle's logical work in this area is considered by

some to be an anticipation of modal logic

and its treatment of potentiality and time. Indeed, many philosophical

interpretations of possibility are related to a famous passage on

Aristotle's On Interpretation, concerning the truth of the statement: "There will be a sea battle tomorrow".

Contemporary philosophy regards possibility, as studied by modal metaphysics, to be an aspect of modal logic. Modal logic as a named subject owes much to the writings of the Scholastics, in particular William of Ockham and John Duns Scotus, who reasoned informally in a modal manner, mainly to analyze statements about essence and accident.

Influence on modern physics

Aristotle's metaphysics, his account of nature and causality, was for the most part rejected by the early modern philosophers. Francis Bacon in his Novum Organon

in one explanation of the case for rejecting the concept of a formal

cause or "nature" for each type of thing, argued for example that

philosophers must still look for formal causes but only in the sense of

"simple natures" such as colour, and weight, which exist in many gradations and modes in very different types of individual bodies. In the works of Thomas Hobbes then, the traditional Aristotelian terms, "potentia et actus", are discussed, but he equates them simply to "cause and effect".

Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz, the source of the modern adaptations of Aristotle's concepts of potentiality and actuality.

There was an adaptation of at least one aspect of Aristotle's

potentiality and actuality distinction, which has become part of modern

physics, although as per Bacon's approach it is a generalized form of

energy, not one connected to specific forms for specific things. The

definition of energy in modern physics as the product of mass and the square of velocity, was derived by Leibniz, as a correction of Descartes, based upon Galileo's investigation of falling bodies. He preferred to refer to it as an entelecheia or "living force" (Latin vis viva), but what he defined is today called "kinetic energy", and was seen by Leibniz as a modification of Aristotle's energeia,

and his concept of the potential for movement which is in things.

Instead of each type of physical thing having its own specific tendency

to a way of moving or changing, as in Aristotle, Leibniz said that

instead, force, power, or motion itself could be transferred between

things of different types, in such a way that there is a general conservation of this energy.

In other words, Leibniz's modern version of entelechy or energy obeys

its own laws of nature, whereas different types of things do not have

their own separate laws of nature. Leibniz wrote:

...the entelechy of Aristotle, which has made so much noise, is nothing else but force or activity ; that is, a state from which action naturally flows if nothing hinders it. But matter, primary and pure, taken without the souls or lives which are united to it, is purely passive ; properly speaking also it is not a substance, but something incomplete.

Leibniz's study of the "entelechy" now known as energy was a part of

what he called his new science of "dynamics", based on the Greek word dunamis

and his understanding that he was making a modern version of

Aristotle's old dichotomy. He also referred to it as the "new science of

power and action", (Latin "potentia et effectu" and "potentia et actione"). And it is from him that the modern distinction between statics and dynamics in physics stems. The emphasis on dunamis in the name of this new science comes from the importance of his discovery of potential energy

which is not active, but which conserves energy nevertheless. "As 'a

science of power and action', dynamics arises when Leibniz proposes an

adequate architectonic of laws for constrained, as well as

unconstrained, motions."

For Leibniz, like Aristotle, this law of nature concerning entelechies was also understood as a metaphysical law, important not only for physics, but also for understanding life and the soul. A soul, or spirit, according to Leibniz, can be understood as a type of entelechy (or living monad) which has distinct perceptions and memory.

Entelecheia in modern philosophy and biology

As discussed above, terms derived from dunamis and energeia

have become parts of modern scientific vocabulary with a very different

meaning from Aristotle's. The original meanings are not used by modern

philosophers unless they are commenting on classical or medieval

philosophy. In contrast, entelecheia, in the form of "entelechy" is a word used much less in technical senses in recent times.

As mentioned above, the concept had occupied a central position in the metaphysics of Leibniz, and is closely related to his monad

in the sense that each sentient entity contains its own entire universe

within it. But Leibniz' use of this concept influenced more than just

the development of the vocabulary of modern physics. Leibniz was also

one of the main inspirations for the important movement in philosophy

known as German Idealism, and within this movement and schools influenced by it entelechy may denote a force propelling one to self-fulfillment.

In the biological vitalism of Hans Driesch, living things develop by entelechy,

a common purposive and organising field. Leading vitalists like Driesch

argued that many of the basic problems of biology cannot be solved by a

philosophy in which the organism is simply considered a machine.

Vitalism and its concepts like entelechy have since been discarded as

without value for scientific practice by the overwhelming majority of

professional biologists.

However, in philosophy aspects and applications of the concept of

entelechy have been explored by scientifically interested philosophers

and philosophically inclined scientists alike. One example was the

American critic and philosopher Kenneth Burke (1897–1993) whose concept of the "terministic screens" illustrates his thought on the subject. Most prominent was perhaps the German quantum physicist Werner Heisenberg.

He looked to the notions of potentiality and actuality in order to

better understand the relationship of quantum theory to the world.

Prof Denis Noble

argues that, just as teleological causation is necessary to the social

sciences, a specific teleological causation in biology, expressing

functional purpose, should be restored and that it is already implicit

in neo-Darwinism (e.g. "selfish gene"). Teleological analysis proves

parsimonious when the level of analysis is appropriate to the complexity

of the required 'level' of explanation (e.g. whole body or organ rather

than cell mechanism).