From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The theory of divine right was developed by

James VI of Scotland (1567–1625), and came to the fore in England under his reign as James I of England (1603–1625). Portrait attributed to

John de Critz, c. 1605

The

divine right of kings,

divine right, or

God's mandate is a political and religious doctrine of royal and

political legitimacy.

It stems from a specific metaphysical framework in which the king (or

queen) is pre-selected as an heir prior to their birth. By pre-selecting

the king's physical manifestation, the governed populace actively

(rather than merely passively) hands the metaphysical selection of the

king's soul – which will inhabit the body and thereby rule them – over

to God. In this way, the "divine right" originates as a metaphysical act

of humility or submission towards the

Godhead. Consequentially, it asserts that a

monarch (e.g. a king) is subject to no earthly authority, deriving the right to rule directly from a divine authority, like the

monotheist will of God. The monarch is thus not subject to the will of his people, of the

aristocracy, or of any other

estate of the realm.

It implies that only divine authority can judge an unjust monarch and

that any attempt to depose, dethrone or restrict their powers runs

contrary to God's will and may constitute a sacrilegious act. It is

often expressed in the phrase "

by the Grace of God", attached to the titles of a reigning monarch; although this right does not make the monarch the same as a

sacred king. The divine right has been a key element for legitimizing many

absolute monarchies.

Pre-Christian conceptions

The

Imperial cult of ancient Rome identified

Roman emperors and some members of their families with the "divinely sanctioned" authority (

auctoritas) of the

Roman State. The official offer of

cultus

to a living emperor acknowledged his office and rule as divinely

approved and constitutional: his Principate should therefore demonstrate

pious respect for traditional Republican deities and

mores.

Many of the rites, practices and status distinctions that characterized

the cult to emperors were perpetuated in the theology and politics of

the Christianized Empire.

Christian origins

Outside of Christianity,

kings were often seen as either ruling with the backing of heavenly

powers or perhaps even being divine beings themselves. However, the

Christian notion of a divine right of kings is traced to a story found

in

1 Samuel, where the prophet

Samuel anoints

Saul and then

David as

mashiach

or king over Israel. The anointing is to such an effect that the

monarch became inviolable, so that even when Saul sought to kill David,

David would not raise his hand against him because "he was the Lord's

anointed".

Although the later Roman Empire had developed the European concept of a divine regent in Late Antiquity,

Adomnan of Iona

provides one of the earliest written examples of a Western medieval

concept of kings ruling with divine right. He wrote of the Irish King

Diarmait mac Cerbaill's

assassination and claimed that divine punishment fell on his assassin

for the act of violating the monarch. Adomnan also recorded a story

about Saint

Columba supposedly being visited by an angel carrying a glass book, who told him to ordain

Aedan mac Gabrain as King of

Dal Riata.

Columba initially refused, and the angel answered by whipping him and

demanding that he perform the ordination because God had commanded it.

The same angel visited Columba on three successive nights. Columba

finally agreed, and Aedan came to receive ordination. At the ordination

Columba told Aedan that so long as he obeyed God's laws, then none of

his enemies would prevail against him, but the moment he broke them,

this protection would end, and the same whip with which Columba had been

struck would be turned against the king. Adomnan's writings most likely

influenced other Irish writers, who in turn influenced continental

ideas as well.

Pepin the Short's coronation may have also come from the same influence. The

Byzantine Empire can be seen as the progenitor of this concept (which began with

Constantine I), which in turn inspired the

Carolingian dynasty and the

Holy Roman Emperors, whose lasting impact on Western and Central Europe further inspired all subsequent Western ideas of kingship.

Scots texts of James VI of Scotland

The

Scots

textbooks of the divine right of kings were written in 1597–1598 by

James VI of Scotland despite Scotland never having believed in the

theory and where the monarch was regarded as the "first among equals" on

a par with his people. His

Basilikon Doron, a manual on the powers of a king, was written to edify his four-year-old son

Henry Frederick

that a king "acknowledgeth himself ordained for his people, having

received from the god a burden of government, whereof he must be

countable". He based his theories in part on his understanding of the

Bible, as noted by the following quote from a speech to parliament

delivered in 1610 as James I of England:

The state of monarchy is the

supremest thing upon earth, for kings are not only God's lieutenants

upon earth and sit upon God's throne, but even by God himself, they are

called gods. There be three principal [comparisons] that illustrate the

state of monarchy: one taken out of the word of God, and the two other

out of the grounds of policy and philosophy. In the Scriptures, kings

are called gods, and so their power after a certain relation compared to

the Divine power. Kings are also compared to fathers of families; for a

king is true parens patriae [parent of the country], the politic

father of his people. And lastly, kings are compared to the head of

this microcosm of the body of man.

James's reference to "God's lieutenants" is apparently a reference to

the text in Romans 13 where Paul refers to "God's ministers".

(1) Let every soul be subject unto

the higher powers. For there is no power but of God: the powers that be

are ordained of God. (2) Whosoever, therefore, resisteth the power,

resisteth the ordinance of God: and they that resist shall receive to

themselves damnation. (3) For rulers are not a terror to good works, but

to the evil. Wilt thou then not be afraid of the power? do that which

is good, and thou shalt have praise of the same: (4) For he is the

minister of God to thee for good. But if thou do that which is evil, be

afraid; for he beareth not the sword in vain: for he is the minister of

God, a revenger to execute wrath upon him that doeth evil. (5) Wherefore

ye must needs be subject, not only for wrath, but also for conscience

sake. (6) For this cause pay ye tribute also: for they are God's

ministers, attending continually upon this very thing. (7) Render

therefore to all their dues: tribute to whom tribute is due; custom to

whom custom; fear to whom fear; honour to whom honour.

Western conceptions

The conception of

ordination brought with it largely unspoken parallels with the

Anglican and

Catholic priesthood,

but the overriding metaphor in James's handbook was that of a father's

relation to his children. "Just as no misconduct on the part of a father

can free his children from obedience to the

fifth commandment", James also had printed his

Defense of the Right of Kings

in the face of English theories of inalienable popular and clerical

rights. The divine right of kings, or divine-right theory of kingship,

is a political and religious doctrine of royal and political legitimacy.

It asserts that a monarch is subject to no earthly authority, deriving

his right to rule directly from the will of God. The king is thus not

subject to the will of his people, the aristocracy, or any other estate

of the realm, including (in the view of some, especially in Protestant

countries) the church. A weaker or more moderate form of this political

theory does hold, however, that the king is subject to the church and

the pope, although completely irreproachable in other ways; but

according to this doctrine in its strong form, only God can judge an

unjust king. The doctrine implies that any attempt to depose the king or

to restrict his powers runs contrary to the will of God and may

constitute a sacrilegious act.

It is related to the ancient Catholic philosophies regarding monarchy, in which the monarch is God's

vicegerent

upon the earth and therefore subject to no inferior power. However, in

Roman Catholic jurisprudence, the monarch is always subject to

natural and

divine law,

which are regarded as superior to the monarch. The possibility of

monarchy declining morally, overturning natural law, and degenerating

into a tyranny oppressive of the general welfare was answered

theologically with the Catholic concept of extra-legal

tyrannicide, ideally ratified by the pope. Until the

unification of Italy, the

Holy See did, from the time Christianity became the Roman

state religion, assert on that ground its primacy over secular princes; however this exercise of power never, even at its zenith, amounted to

theocracy, even in jurisdictions where the Bishop of Rome was the temporal authority.

Antichristus, a woodcut by

Lucas Cranach the Elder, of the pope using the temporal power to grant authority to a ruler contributing generously to the Catholic Church

Catholic justified permission

Catholic thought justified submission to the monarchy by reference to the following:

- The Old Testament, in which God chose kings to rule over Israel, beginning with Saul who was then rejected by God in favor of David, whose dynasty continued (at least in the southern kingdom) until the Babylonian captivity.

- The New Testament, in which the first pope, St. Peter, commands that all Christians shall honour the Roman Emperor (1 Peter 2:13–20),

even though, at that time, he was still a pagan emperor. St. Paul

agreed with St. Peter that subjects should be obedient to the powers

that be because they are appointed by God, as he wrote in his Epistle to

the Romans 13:1–7.

Likewise, Jesus Christ proclaims in the Gospel of Matthew that one

should "Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar's"; that is at

first, literally, the payment of taxes as binding those who use the

imperial currency (See Matthew 22:15–22). Jesus told Pontius Pilate that his authority as Roman governor of Judaea came from heaven according to John 19:10–11.

- The endorsement by the popes and the church of the line of emperors beginning with the Emperors Constantine and Theodosius, later the Eastern Roman emperors, and finally the Western Roman emperor, Charlemagne and his successors, the Catholic Holy Roman Emperors.

The French Huguenot nobles and clergy, having rejected the pope and

the Catholic Church, were left only with the supreme power of the king

who, they taught, could not be gainsaid or judged by anyone. Since there

was no longer the countervailing power of the papacy and since the

Church of England was a creature of the state and had become subservient

to it, this meant that there was nothing to regulate the powers of the

king, and he became an absolute power. In theory,

divine,

natural, customary, and

constitutional law

still held sway over the king, but, absent a superior spiritual power,

it was difficult to see how they could be enforced, since the king could

not be tried by any of his own courts.

Some of the symbolism within the

coronation ceremony for British monarchs, in which they are

anointed with

holy oils by the

Archbishop of Canterbury, thereby

ordaining

them to monarchy, perpetuates the ancient Roman Catholic monarchical

ideas and ceremonial (although few Protestants realize this, the

ceremony is nearly entirely based upon that of the Coronation of the

Holy Roman Emperor).

However, in the UK, the symbolism ends there, since the real governing

authority of the monarch was all but extinguished by the Whig revolution

of 1688–89. The king or queen of the

United Kingdom

is one of the last monarchs still to be crowned in the traditional

Christian ceremonial, which in most other countries has been replaced by

an

inauguration or other declaration.

The concept of divine right incorporates, but exaggerates, the

ancient Christian concept of "royal God-given rights", which teach that

"the right to rule is anointed by God", although this idea is found in

many other cultures, including

Aryan and

Egyptian

traditions. In pagan religions, the king was often seen as a kind of

god and so was an unchallengeable despot. The ancient Roman Catholic

tradition overcame this idea with the doctrine of the "Two Swords" and

so achieved, for the very first time, a balanced constitution for

states. The advent of Protestantism saw something of a return to the

idea of a mere unchallengeable despot.

When there is no recourse to a

superior by whom judgment can be made about an invader, then he who

slays a tyrant to liberate his fatherland is [to be] praised and

receives a reward.

— Commentary on the Magister Sententiarum

On the other hand, Aquinas forbade the overthrow of any morally,

Christianly and spiritually legitimate king by his subjects. The only

human power capable of deposing the king was the pope. The reasoning was

that if a subject may overthrow his superior for some bad law, who was

to be the judge of whether the law was bad? If the subject could so

judge his own superior, then all lawful superior authority could

lawfully be overthrown by the arbitrary judgement of an inferior, and

thus all law was under constant threat. Towards the end of the Middle

Ages, many philosophers, such as

Nicholas of Cusa and

Francisco Suarez,

propounded similar theories. The Church was the final guarantor that

Christian kings would follow the laws and constitutional traditions of

their ancestors and the laws of God and of justice. Similarly, the

Chinese concept of

Mandate of Heaven required that the emperor properly carry out the proper

rituals and consult his ministers; however, this concept made it extremely difficult to undo any acts carried out by an ancestor.

The French prelate

Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet made a classic statement of the doctrine of divine right in a sermon preached before King Louis XIV:

Les rois règnent par moi, dit la

Sagesse éternelle: 'Per me reges regnant'; et de là nous devons conclure

non seulement que les droits de la royauté sont établis par ses lois,

mais que le choix des personnes est un effet de sa providence.

Kings reign by Me, says Eternal

Wisdom: 'Per me reges regnant' [in Latin]; and from that we must

conclude not only that the rights of royalty are established by its

laws, but also that the choice of persons [to occupy the throne] is an

effect of its providence.

Divine right and Protestantism

Before the Reformation the anointed

king was, within his

realm, the accredited vicar of God for secular purposes; after the Reformation he (or she if

queen regnant) became this in Protestant states for religious purposes also.

In England it is not without significance that the sacerdotal

vestments, generally discarded by the clergy – dalmatic, alb and stole –

continued to be among the insignia of the sovereign (see

Coronation of the British monarch).

Moreover, this sacrosanct character he acquired not by virtue of his

"sacring", but by hereditary right; the coronation, anointing and

vesting were but the outward and visible symbol of a divine grace

adherent in the sovereign by virtue of his title. Even Roman Catholic

monarchs, like

Louis XIV,

would never have admitted that their coronation by the archbishop

constituted any part of their title to reign; it was no more than the

consecration of their title.

In England the doctrine of the divine right of kings was

developed to its most extreme logical conclusions during the political

controversies of the 17th century; its most famous exponent was Sir

Robert Filmer. It was the main issue to be decided by the

English Civil War, the

Royalists holding that "all Christian kings, princes and governors" derive their authority direct from God, the

Parliamentarians that this authority is the outcome of a contract, actual or implied, between sovereign and people.

In one case the king's power would be unlimited, according to Louis XIV's famous saying:

"L' état, c'est moi!",

or limited only by his own free act; in the other his actions would be

governed by the advice and consent of the people, to whom he would be

ultimately responsible. The victory of this latter principle was

proclaimed to all the world by the

execution of Charles I. The doctrine of divine right, indeed, for a while drew nourishment from the blood of the royal "martyr"; it was the guiding principle of the

Anglican Church of the

Restoration; but it suffered a rude blow when

James II of England made it impossible for the clergy to obey both their conscience and their king. The

Glorious Revolution of 1688 made an end of it as a great political force. This has led to the constitutional development of

the Crown in Britain, as held by descent modified and modifiable by parliamentary action.

Iranian world

Khvarenah (

Avestan: '

xᵛarənah;' Persian:

far) is an Iranian and

Zoroastrian concept, which literally means

glory,

about divine right of the kings. In Iranian view, kings would never

rule, unless Khvarenah is with them, and they will never fall unless

Khvarenah leaves them. For example, according to the

Kar-namag of Ardashir, when

Ardashir I of Persia and

Artabanus V of Parthia

fought for the throne of Iran, on the road Artabanus and his contingent

are overtaken by an enormous ram, which is also following Ardashir.

Artabanus's religious advisors explain to him that the ram is the

manifestation of the

khwarrah of the ancient Iranian kings, which is leaving Artabanus to join Ardashir.

Divine right in Asia

In early Mesopotamian culture, kings were often regarded as deities after their death.

Shulgi of

Ur

was among the first Mesopotamian rulers to declare himself to be

divine. This was the direct precursor to the concept of "Divine Right of

kings", as well as in the Egyptian and Roman religions.

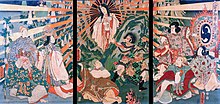

Mandate of Heaven

In

China and

East Asia, rulers justified their rule with the philosophy of the

Mandate of Heaven,

which, although similar to the European concept, bore several key

differences. While the divine right of kings granted unconditional

legitimacy, the Mandate of Heaven was dependent on the behaviour of the

ruler, the

Son of Heaven.

Heaven

would bless the authority of a just ruler, but it could be displeased

with a despotic ruler and thus withdraw its mandate, transferring it to a

more suitable and righteous person. This withdrawal of mandate also

afforded the possibility of revolution as a means to remove the errant

ruler; revolt was never legitimate under the European framework of

divine right.

In China, the

right of rebellion against an unjust ruler had been a part of the political philosophy ever since the

Zhou dynasty, whose rulers had used this philosophy to justify their overthrow of the previous

Shang dynasty. Chinese historians interpreted a successful revolt as evidence that the Mandate of Heaven had passed on to the usurper.

In Japan, the Son of Heaven title was less conditional than its

Chinese equivalent. There was no divine mandate that punished the

emperor for failing to rule justly. The right to rule of the Japanese

emperor, descended from the sun goddess

Amaterasu, was absolute.

The Japanese emperors traditionally wielded little secular power;

generally, it was the duty of the sitting emperor to perform rituals and

make public appearances, while true power was held by regents,

high-ranking ministers, a commander-in-chief of the emperor's military

known as the

shōgun, or even retired emperors depending on the time period.

Sultans in Southeast Asia

In the

Malay Annals, the

rajas and

sultans of the Malay States (today

Malaysia,

Brunei and

Philippines) as well as their predecessors, such as the

Indonesian kingdom of

Majapahit,

also claimed divine right to rule. The sultan is mandated by God and

thus is expected to lead his country and people in religious matters,

ceremonies as well as prayers. This divine right is called

Daulat (which means 'state' in Arabic), and although the notion of divine right is somewhat obsolete, it is still found in the phrase

Daulat Tuanku that is used to publicly acclaim the reigning

Yang di-Pertuan Agong and the other sultans of Malaysia. The exclamation is similar to the European "

Long live the King", and often accompanies pictures of the reigning monarch and

his consort on banners during royal occasions. In

Indonesia, especially on the island of

Java, the sultan's divine right is more commonly known as the

way, or 'revelation', but it is not hereditary and can be passed on to distant relatives.

South Asian kings

In

Dravidian culture, before

Brahmanism and especially during the

Sangam period, emperors were known as இறையர் (

Iraiyer), or "those who spill", and kings were called கோ (

Ko) or கோன் (

Kon). During this time, the distinction between kingship and godhood had not yet occurred, as the

caste system had not yet been introduced. Even in Modern

Tamil, the word for temple is 'கோயில்', meaning "king's house". Kings were understood to be the "agents of God", as they protected the world like God did. This may well have been continued post-Brahminism in

Tamilakam, as the famous Thiruvalangadu inscription states:

"Having noticed by the marks (on his body) that Arulmozhi was the very Vishnu" in reference to the Emperor Raja Raja Chola I.

Rights

Historically, many notions of

rights were

authoritarian and

hierarchical,

with different people granted different rights, and some having more

rights than others. For instance, the right of a father to respect from

his son did not indicate a right for the son to receive a return from

that respect; and the divine right of kings, which permitted absolute

power over subjects, did not leave a lot of room for many rights for the

subjects themselves.

Opposition

In the sixteenth century, both Catholic and Protestant political

thinkers began to question the idea of a monarch's "divine right".

The Spanish Catholic historian

Juan de Mariana put forward the argument in his book

De rege et regis institutione

(1598) that since society was formed by a "pact" among all its members,

"there can be no doubt that they are able to call a king to account". Mariana thus challenged divine right theories by stating in certain circumstances,

tyrannicide could be justified.

Cardinal Robert Bellarmine

also "did not believe that the institute of monarchy had any divine

sanction" and shared Mariana's belief that there were times where

Catholics could lawfully remove a monarch.

Among groups of English

Protestant exiles fleeing from

Queen Mary I,

some of the earliest anti-monarchist publications emerged. "Weaned off

uncritical royalism by the actions of Queen Mary ... The political

thinking of men like

Ponet,

Knox,

Goodman and Hales."

In 1553, Mary I, a Roman Catholic, succeeded her Protestant half-brother,

Edward VI,

to the English throne. Mary set about trying to restore Roman

Catholicism by making sure that: Edward's religious laws were abolished

in the Statute of Repeal Act (1553); the Protestant religious laws

passed in the time of

Henry VIII were repealed; and the

Revival of the Heresy Acts were passed in 1554. The

Marian Persecutions began soon afterwards. In January 1555, the first of nearly 300 Protestants were burnt at the stake under "Bloody Mary". When

Thomas Wyatt the Younger instigated what became known as

Wyatt's rebellion,

John Ponet, the highest-ranking ecclesiastic among the exiles, allegedly participated in the uprising. He escaped to

Strasbourg after the Rebellion's defeat and, the following year, he published

A Shorte Treatise of Politike Power, in which he put forward a theory of justified opposition to secular rulers.

"Ponet's treatise comes first in a new wave of anti-monarchical

writings ... It has never been assessed at its true importance, for it

antedates by several years those more brilliantly expressed but less

radical

Huguenot writings which have usually been taken to represent the

Tyrannicide-theories of the

Reformation."

According to U.S. President

John Adams, Ponet's work contained "all the essential principles of liberty, which were afterward dilated on by

Sidney and

Locke", including the idea of a three-branched government.