Ritalin sustained-release (SR) 20 mg tablets

Stimulants (also often referred to as psychostimulants or colloquially as uppers) is an overarching term that covers many drugs including those that increase activity of the central nervous system and the body, drugs that are pleasurable and invigorating, or drugs that have sympathomimetic effects. Stimulants are widely used throughout the world as prescription medicines as well as without a prescription (either legally or illicitly) as performance-enhancing or recreational drugs. The most frequently prescribed stimulants as of 2013 were lisdexamfetamine, methylphenidate, and amphetamine. It is estimated that the percentage of the population that has used amphetamine-type stimulants (e.g., amphetamine, methamphetamine, MDMA, etc.) and cocaine combined is between 0.8% and 2.1%.

Effects

Acute

Stimulants in therapeutic doses, such as those given to patients with ADHD,

increases ability to focus, vigor, sociability, libido and may elevate

mood. However, in higher doses stimulants may actually decrease the

ability to focus, a principle of the Yerkes-Dodson Law. In higher doses stimulants may also produce euphoria, vigor, and decrease need for sleep. Many, but not all, stimulants have ergogenic

effects. Drugs such as ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, amphetamine and

methylphenidate have well documented ergogenic effects, while cocaine

has the opposite effect. Neurocognitive enhancing effects of stimulants, specifically modafinil,

amphetamine and methylphenidate have been documented in healthy

adolescents, and is a commonly cited reason among illicit drug users for

use, particularly among college students in the context of studying.

In some cases psychiatric phenomenon may emerge such as stimulant psychosis, paranoia, and suicidal ideation. Acute toxicity has been reportedly associated with a homicide, paranoia, aggressive behavior, motor dysfunction, and punding. The violent and aggressive behavior associated with acute stimulant toxicity may partially be driven by paranoia.

Most drugs classified as stimulants are sympathomimetics, that is they

stimulate the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system. This

leads to effects such as mydriasis, increased heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate and body temperature. When these changes become pathological, they are called arrhythmia, hypertension, and hyperthermia, and may lead to rhabdomyolysis, stroke, cardiac arrest, or seizures.

However, given the complexity of the mechanisms that underlie these

potentially fatal outcomes of acute stimulant toxicity, it is impossible

to determine what dose may be lethal.

Chronic

Assessment

of the effects of stimulants is relevant given the large population

currently taking stimulants. A systematic review of cardiovascular

effects of prescription stimulants found no association in children, but

found a correlation between prescription stimulant use and ischemic

heart attacks.

A review over a four-year period found that there were few negative

effects of stimulant treatment, but stressed the need for longer-term

studies. A review of a year long period of prescription stimulant use in those with ADHD found that cardiovascular side effects were limited to transient increases in blood pressure only.

Initiation of stimulant treatment in those with ADHD in early childhood

appears to carry benefits into adulthood with regard to social and

cognitive functioning, and appears to be relatively safe.

Abuse of prescription stimulants (not following physician

instruction) or of illicit stimulants carries many negative health

risks. Abuse of cocaine, depending upon route of administration,

increases risk of cardiorespiratory disease, stroke, and sepsis.

Some effects are dependent upon the route of administration, with

intravenous use associated with the transmission of many disease such as

Hepatitis C, HIV/AIDS and potential medical emergencies such as infection, thrombosis or pseudoaneurysm, while inhalation may be associated with increased lower respiratory tract infection, lung cancer, and pathological restricting of lung tissue. Cocaine may also increase risk for autoimmune disease

and damage nasal cartilage. Abuse of methamphetamine produces similar

effects as well as marked degeneration of dopaminergic neurons,

resulting in an increased risk for Parkinson's disease.

Medical uses

Stimulants have been used in medicine for many conditions including obesity, sleep disorders, mood disorders, impulse control disorders, asthma, nasal congestion and, in case of cocaine, as local anesthetics. Drugs used to treat obesity are called anorectics and generally include drugs that follow the general definition of a stimulant, but other drugs such as cannabinoid receptor antagonists also belong to this group. Eugeroics are used in management of sleep disorders characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness, such as narcolepsy, and include stimulants such as modafinil. Stimulants are used in impulse control disorders such as ADHD and off-label in mood disorders such as major depressive disorder to increase energy, focus and elevate mood. Stimulants such as epinephrine, theophylline and salbutamol orally have been used to treat asthma, but inhaled adrenergic drugs are now preferred due to less systemic side effects. Pseudoephedrine

is used to relieve nasal or sinus congestion caused by the common cold,

sinusitis, hay fever and other respiratory allergies; it is also used

to relieve ear congestion caused by ear inflammation or infection.

Chemistry

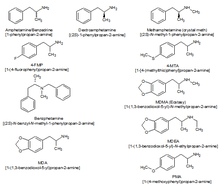

A chart comparing the chemical structures of different amphetamine derivatives

Classifying stimulants is difficult, because of the large number of

classes the drugs occupy, and the fact that they may belong to multiple

classes; for example, ecstasy can be classified as a substituted methylenedioxyphenethylamine, a substituted amphetamine and consequently, a substituted phenethylamine.

When referring to stimulants, the parent drug (e.g., amphetamine) will always be expressed in the singular; with the word "substituted" placed before the parent drug (substituted amphetamines).

Major stimulant classes include phenethylamines and their daughter class substituted amphetamines.

Amphetamines (class)

Substituted amphetamines are a class of compounds based upon the amphetamine structure; it includes all derivative compounds which are formed by replacing, or substituting, one or more hydrogen atoms in the amphetamine core structure with substituents. Examples of substituted amphetamines are amphetamine (itself), methamphetamine, ephedrine, cathinone, phentermine, mephentermine, bupropion, methoxyphenamine, selegiline, amfepramone, pyrovalerone, MDMA (ecstasy), and DOM (STP). Many drugs in this class work primarily by activating trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1); in turn, this causes reuptake inhibition and effluxion, or release, of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. An additional mechanism of some substituted amphetamines is the release of vesicular stores of monoamine neurotransmitters through VMAT2, thereby increasing the concentration of these neurotransmitters in the cytosol, or intracellular fluid, of the presynaptic neuron.

Amphetamines-type stimulants are often used for their therapeutic effects. Physicians sometimes prescribe amphetamine to treat major depression, where subjects do not respond well to traditional SSRI medications,[citation needed] but evidence supporting this use is poor/mixed. Notably, two recent large phase III studies of lisdexamfetamine (a prodrug to amphetamine) as an adjunct to an SSRI or SNRI in the treatment of major depressive disorder showed no further benefit relative to placebo in effectiveness. Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of drugs such as Adderall (a mixture of salts of amphetamine and dextroamphetamine) in controlling symptoms associated with ADHD. Due to their availability and fast-acting effects, substituted amphetamines are prime candidates for abuse.

Cocaine analogues

Hundreds of cocaine analogues have been created, all of them usually

maintaining a benzyloxy connected to the 3 carbon of a tropane. Various

modifications include substitutions on the benzene ring, as well as

additions or substitutions in place of the normal carboxylate on the

tropane 2 carbon. Various compound with similar structure activity

relationships to cocaine that aren't technically analogues have been

developed as well.

Mechanisms of action

Most stimulants exert their activating effects by enhancing catecholamine

neurotranmission. Catecholamine neurotransmitters are employed in

regulatory pathways implicated in attention, arousal, motivation, task

salience and reward anticipation. Classical stimulants either block the reuptake or stimulate the efflux of these catecholamines, resulting in increased activity of their circuits. Some stimulants, specifically those with empathogenic and hallucinogenic effects, also affect serotonergic transmission. Some stimulants, such as some amphetamine derivatives and, notably, yohimbine, can decrease negative feedback by antagonizing regulatory autoreceptors. Adrenergic agonists, such as, in part, ephedrine, act by directly binding to and activating adrenergic receptors, producing sympathomimetic effects.

There are also more indirect mechanisms a drug can elicit activating effects. Caffeine is an adenosine receptor antagonist, and only indirectly increases catecholamine transmission in the brain. Pitolisant is an H3-receptor inverse agonist. As H3 receptors mainly act as autoreceptors, pitolisant decreases negative feedback to histaminergic neurons, enhancing histaminergic transmission.

Notable stimulants

Amphetamine

Amphetamine is a potent central nervous system (CNS) stimulant of the phenethylamine class that is approved for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy. Amphetamine is also used off-label as a performance and cognitive enhancer, and recreationally as an aphrodisiac and euphoriant.

Although it is a prescription medication in many countries,

unauthorized possession and distribution of amphetamine is often tightly

controlled due to the significant health risks associated with

uncontrolled or heavy use. As a consequence, amphetamine is illegally manufactured in clandestine labs to be trafficked and sold to users. Based upon drug and drug precursor seizures worldwide, illicit amphetamine production and trafficking is much less prevalent than that of methamphetamine.

The first pharmaceutical amphetamine was Benzedrine, a brand of inhalers used to treat a variety of conditions.

Because the dextrorotary isomer has greater stimulant properties,

Benzedrine was gradually discontinued in favor of formulations

containing all or mostly dextroamphetamine. Presently, it is typically

prescribed as mixed amphetamine salts, dextroamphetamine, and lisdexamfetamine.

Amphetamine is a norepinephrine-dopamine releasing agent (NDRA). It enters neurons through dopamine and norepinephrine transporters and facilitates neurotransmitter efflux by activating TAAR1 and inhibiting VMAT2.

At therapeutic doses, this causes emotional and cognitive effects such

as euphoria, change in libido, increased arousal, and improved cognitive control. Likewise, it induces physical effects such as decreased reaction time, fatigue resistance, and increased muscle strength. In contrast, supratherapeutic doses of amphetamine are likely to impair cognitive function and induce rapid muscle breakdown. Very high doses can result in psychosis (e.g., delusions and paranoia), which very rarely occurs at therapeutic doses even during long-term use.[58][59]

As recreational doses are generally much larger than prescribed

therapeutic doses, recreational use carries a far greater risk of

serious side effects, such as dependence, which only rarely arises with

therapeutic amphetamine use.

Caffeine

Caffeine is a stimulant compound belonging to the xanthine class of chemicals naturally found in coffee, tea, and (to a lesser degree) cocoa or chocolate. It is included in many soft drinks, as well as a larger amount in energy drinks.

Caffeine is the world's most widely used psychoactive drug and by far

the most common stimulant. In North America, 90% of adults consume

caffeine daily.

A few jurisdictions restrict its sale and use. Caffeine is also

included in some medications, usually for the purpose of enhancing the

effect of the primary ingredient, or reducing one of its side-effects

(especially drowsiness). Tablets containing standardized doses of

caffeine are also widely available.

Caffeine's mechanism of action differs from many stimulants, as it produces stimulant effects by inhibiting adenosine receptors.

Adenosine receptors are thought to be a large driver of drowsiness and

sleep, and their action increases with extended wakefulness. Caffeine has been found to increase striatal dopamine in animal models, as well as inhibit the inhibitory effect of adenosine receptors on dopamine receptors,

however the implications for humans are unknown. Unlike most

stimulants, caffeine has no addictive potential. Caffeine does not

appear to be a reinforcing stimulus, and some degree of aversion may

actually occur, which people preferring placebo over caffeine in a study

on drug abuse liability published in an NIDA research monograph.

In large telephone surveys only 11% reported dependence symptoms.

However, when people were tested in labs, only half of those who claim

dependence actually experienced it, casting doubt on caffeine's ability

to produce dependence and putting societal pressures in the spotlight.

Coffee consumption is associated with a lower overall risk of cancer. This is primarily due to a decrease in the risks of hepatocellular and endometrial cancer, but it may also have a modest effect on colorectal cancer.

There does not appear to be a significant protective effect against

other types of cancers, and heavy coffee consumption may increase the

risk of bladder cancer. A protective effect of caffeine against Alzheimer's disease is possible, but the evidence is inconclusive. Moderate coffee consumption may decrease the risk of cardiovascular disease, and it may somewhat reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes. Drinking 1-3 cups of coffee per day does not affect the risk of hypertension compared to drinking little or no coffee. However those who drink 2–4 cups per day may be at a slightly increased risk. Caffeine increases intraocular pressure in those with glaucoma but does not appear to affect normal individuals. It may protect people from liver cirrhosis. There is no evidence that coffee stunts a child's growth. Caffeine may increase the effectiveness of some medications including ones used to treat headaches. Caffeine may lessen the severity of acute mountain sickness if taken a few hours prior to attaining a high altitude.

Ephedrine

Ephedrine is a sympathomimetic amine similar in molecular structure to the well-known drugs phenylpropanolamine and methamphetamine, as well as to the important neurotransmitter epinephrine (adrenaline). Ephedrine is commonly used as a stimulant, appetite suppressant, concentration aid, and decongestant, and to treat hypotension associated with anaesthesia.

In chemical terms, it is an alkaloid with a phenethylamine skeleton found in various plants in the genus Ephedra (family Ephedraceae). It works mainly by increasing the activity of norepinephrine (noradrenaline) on adrenergic receptors. It is most usually marketed as the hydrochloride or sulfate salt.

The herb má huáng (Ephedra sinica), used in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), contains ephedrine and pseudoephedrine as its principal active constituents. The same may be true of other herbal products containing extracts from other Ephedra species.

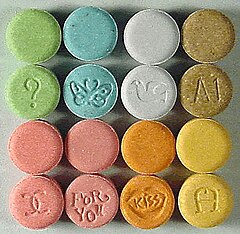

MDMA

Tablets containing MDMA

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ecstasy, or molly) is a euphoriant, empathogen, and stimulant of the amphetamine class. Briefly used by some psychotherapists as an adjunct to therapy, the drug became popular recreationally and the DEA listed MDMA as a Schedule I controlled substance, prohibiting most medical studies and applications. MDMA is known for its entactogenic properties. The stimulant effects of MDMA include hypertension, anorexia (appetite loss), euphoria, social disinhibition, insomnia (enhanced wakefulness/inability to sleep), improved energy, increased arousal, and increased perspiration,

among others. Relative to catecholaminergic transmission, MDMA enhances

serotonergic transmission significantly more, when compared to

classical stimulants like amphetamine. MDMA does not appear to be

significantly addictive or dependence forming.

Due to the relative safety of MDMA, some researchers such as David Nutt

have criticized the scheduling level, writing a satirical article

finding MDMA to be 28 times less dangerous than horseriding, a condition

he termed "equasy" or "Equine Addiction Syndrome".

MDPV

Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) is a psychoactive drug with stimulant properties that acts as a norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI). It was first developed in the 1960s by a team at Boehringer Ingelheim. MDPV remained an obscure stimulant until around 2004, when it was reported to be sold as a designer drug. Products labeled as bath salts

containing MDPV were previously sold as recreational drugs in gas

stations and convenience stores in the United States, similar to the

marketing for Spice and K2 as incense.

Incidents of psychological and physical harm have been attributed to MDPV use.

Mephedrone

Mephedrone is a synthetic stimulant drug of the amphetamine and cathinone classes. Slang names include drone and MCAT. It is reported to be manufactured in China and is chemically similar to the cathinone compounds found in the khat plant of eastern Africa. It comes in the form of tablets or a powder, which users can swallow, snort, or inject, producing similar effects to MDMA, amphetamines, and cocaine.

Mephedrone was first synthesized in 1929, but did not become

widely known until it was rediscovered in 2003. By 2007, mephedrone was

reported to be available for sale on the Internet; by 2008 law

enforcement agencies had become aware of the compound; and, by 2010, it

had been reported in most of Europe, becoming particularly prevalent in

the United Kingdom. Mephedrone was first made illegal in Israel in 2008,

followed by Sweden later that year. In 2010, it was made illegal in

many European countries, and, in December 2010, the EU ruled it illegal.

In Australia, New Zealand, and the US, it is considered an analog of other illegal drugs and can be controlled by laws similar to the Federal Analog Act. In September 2011, the USA temporarily classified mephedrone as illegal, in effect from October 2011.

Methamphetamine

Methamphetamine (contracted from N-methyl-alpha-methylphenethylamine) is a potent psychostimulant of the phenethylamine and amphetamine classes that is used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and obesity. Methamphetamine exists as two enantiomers, dextrorotary and levorotary. Dextromethamphetamine is a stronger CNS stimulant than levomethamphetamine; however, both are addictive and produce the same toxicity symptoms at high doses. Although rarely prescribed due to the potential risks, methamphetamine hydrochloride is approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) under the trade name Desoxyn. Recreationally, methamphetamine is used to increase sexual desire, lift the mood, and increase energy, allowing some users to engage in sexual activity continuously for several days straight.

Methamphetamine may be sold illicitly, either as pure dextromethamphetamine or in an equal parts mixture of the right- and left-handed molecules (i.e., 50% levomethamphetamine and 50% dextromethamphetamine). Both dextromethamphetamine and racemic methamphetamine are schedule II controlled substances in the United States.

Also, the production, distribution, sale, and possession of

methamphetamine is restricted or illegal in many other countries due to

its placement in schedule II of the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances treaty. In contrast, levomethamphetamine is an over-the-counter drug in the United States.

In low doses, methamphetamine can cause an elevated mood and increase alertness, concentration, and energy in fatigued individuals. At higher doses, it can induce psychosis, rhabdomyolysis, and cerebral hemorrhage. Methamphetamine is known to have a high potential for abuse and addiction. Recreational use of methamphetamine may result in psychosis or lead to post-withdrawal syndrome, a withdrawal syndrome that can persist for months beyond the typical withdrawal period. Unlike amphetamine and cocaine, methamphetamine is neurotoxic to humans, damaging both dopamine and serotonin neurons in the central nervous system (CNS).

Entirely opposite to the long-term use of amphetamine, there is

evidence that methamphetamine causes brain damage from long-term use in

humans; this damage includes adverse changes in brain structure and function, such as reductions in gray matter volume in several brain regions and adverse changes in markers of metabolic integrity.

Methylphenidate

Methylphenidate is a stimulant drug that is often used in the

treatment of ADHD and narcolepsy and occasionally to treat obesity in

combination with diet restraints and exercise. Its effects at

therapeutic doses include increased focus, increased alertness,

decreased appetite, decreased need for sleep and decreased impulsivity.

Methylphenidate is not usually used recreationally, but when it is used,

its effects are very similar to those of amphetamines.

Methylphenidate acts a norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor, by blocking the norepinephrine transporter (NET) and the dopamine transporter

(DAT). Methylphenidate has a higher affinity for the dopamine

transporter than for the norepinephrine transporter, and so its effects

are mainly due to elevated dopamine levels caused by the inhibited

reuptake of dopamine, however increased norepinephrine levels also

contribute to various of the effects caused by the drug.

Methylphenidate is sold under a number of brand names including

Ritalin. Other versions include the long lasting tablet Concerta and the

long lasting transdermal patch Daytrana.

A 2018 Cochrane review found tentative evidence that methylphenidate may result in serious side effects such as heart problems, psychosis, and death.

Cocaine

Lines of illicit cocaine, used as a recreational stimulant

Cocaine is an SNDRI. Cocaine is made from the leaves of the coca shrub, which grows in the mountain regions of South American countries such as Bolivia, Colombia, and Peru.

In Europe, North America, and some parts of Asia, the most common form

of cocaine is a white crystalline powder. Cocaine is a stimulant but is

not normally prescribed therapeutically for its stimulant properties,

although it sees clinical use as a local anesthetic, in particular in ophthalmology.

Most cocaine use is recreational and its abuse potential is high

(higher than amphetamine), and so its sale and possession are strictly

controlled in most jurisdictions. Other tropane derivative drugs related to cocaine are also known such as troparil and lometopane but have not been widely sold or used recreationally.

Nicotine

Nicotine is the active chemical constituent in tobacco, which is available in many forms, including cigarettes, cigars, chewing tobacco, and smoking cessation aids such as nicotine patches, nicotine gum, and electronic cigarettes.

Nicotine is used widely throughout the world for its stimulating and

relaxing effects. Nicotine exerts its effects through the agonism of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, resulting in multiple downstream effects such as increase in activity of dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain reward system, and acetaldehyde one of the tobacco constituent decreased the expression of monoamine oxidase in the brain.

Nicotine is addictive and dependence forming. Tobacco, the most common

source of nicotine, has an overall harm to user and self score 3

percent below cocaine, and 13 percent above amphetamines, ranking 6th

most harmful of the 20 drugs assessed, as determined by a multi-criteria

decision analysis.

Phenylpropanolamine

Phenylpropanolamine (PPA; Accutrim; β-hydroxyamphetamine), also known as the stereoisomers norephedrine and norpseudoephedrine, is a psychoactive drug of the phenethylamine and amphetamine chemical classes that is used as a stimulant, decongestant, and anorectic agent. It is commonly used in prescription and over-the-counter cough and cold preparations. In veterinary medicine, it is used to control urinary incontinence in dogs under trade names Propalin and Proin.

In the United States, PPA is no longer sold without a prescription due to a proposed increased risk of stroke

in younger women. In a few countries in Europe, however, it is still

available either by prescription or sometimes over-the-counter. In

Canada, it was withdrawn from the market on 31 May 2001. In India, human use of PPA and its formulations were banned on 10 February 2011.

Propylhexedrine

Propylhexedrine (Hexahydromethamphetamine, Obesin) is a stimulant

medication, sold over-the-counter in the United States as the cold

medication Benzedrex. The drug has also been used as an appetite suppressant in Europe. Propylhexedrine is not an amphetamine, though it is structurally similar; it is instead a cycloalkylamine, and thus has stimulant effects that are less potent than similarly structured amphetamines, such as methamphetamine.

The abuse potential of propylhexedrine is fairly limited, due its

limited routes of administration: in the United States, Benzedrex is

only available as an inhalant, mixed with lavender oil and menthol.

These ingredients cause unpleasant tastes, and abusers of the drug have

reported unpleasant "menthol burps". Injection of the drug has been

found to cause transient diplopia and brain stem dysfunction.

Pseudoephedrine

Pseudoephedrine is a sympathomimetic drug of the phenethylamine and amphetamine chemical classes. It may be used as a nasal/sinus decongestant, as a stimulant, or as a wakefulness-promoting agent.

The salts pseudoephedrine hydrochloride and pseudoephedrine sulfate are found in many over-the-counter preparations, either as a single ingredient or (more commonly) in combination with antihistamines, guaifenesin, dextromethorphan, and/or paracetamol (acetaminophen) or another NSAID (such as aspirin or ibuprofen). It is also used as a precursor chemical in the illegal production of methamphetamine.

Catha edulis (Khat)

Catha edulis

Khat contains a monoamine alkaloid called cathinone, a "keto-amphetamine", that is said to cause excitement, loss of appetite, and euphoria. In 1980, the World Health Organization (WHO) classified it as a drug of abuse that can produce mild to moderate psychological dependence (less than tobacco or alcohol), although the WHO does not consider khat to be seriously addictive.

It is banned in some countries, such as the United States, Canada, and

Germany, while its production, sale, and consumption are legal in other

nations, including Djibouti, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Yemen.

Recreational use and issues of abuse

Stimulants enhance the activity of the central and peripheral nervous systems. Common effects may include increased alertness, awareness, wakefulness, endurance, productivity, and motivation, arousal, locomotion, heart rate, and blood pressure, and a diminished desire for food and sleep.

Use of stimulants may cause the body to reduce significantly its

production of natural body chemicals that fulfill similar functions.

Until the body reestablishes its normal state, once the effect of the

ingested stimulant has worn off the user may feel depressed, lethargic,

confused, and miserable. This is referred to as a "crash", and may

provoke reuse of the stimulant.

Abuse of central nervous system (CNS) stimulants is common. Addiction to some CNS stimulants can quickly lead to medical, psychiatric, and psychosocial deterioration. Drug tolerance, dependence, and sensitization as well as a withdrawal syndrome can occur.

Stimulants may be screened for in animal discrimination and

self-administration models which have high sensitivity albeit low

specificity. Research on a progressive ratio Self-administration

protocol has found amphetamine, methylphenidate, modafinil, cocaine,

and nicotine to all have a higher break point than placebo that scales

with dose indicating reinforcing effects.

| Drug | Mean | Pleasure | Psychological dependence | Physical dependence. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methamphetamine | 5.53 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 3.0 |

| Cocaine | 2.39 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 1.3 |

| Tobacco | 2.21 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 1.8 |

| Amphetamine | 1.67 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.1 |

| Ecstasy | 1.13 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.7 |

Testing

The

presence of stimulants in the body may be tested by a variety of

procedures. Serum and urine are the common sources of testing material

although saliva is sometimes used. Commonly used tests include

chromatography, immunologic assay, and mass spectrometry.