From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants (also known as angiosperms) formed from the ovary after flowering.

Fruits are the means by which angiosperms disseminate seeds. Edible fruits, in particular, have propagated with the movements of humans and animals in a symbiotic relationship as a means for seed dispersal and nutrition; in fact, humans and many animals have become dependent on fruits as a source of food. Accordingly, fruits account for a substantial fraction of the world's agricultural output, and some (such as the apple and the pomegranate) have acquired extensive cultural and symbolic meanings.

In common language usage, "fruit" normally means the fleshy seed-associated structures of a plant that are sweet or sour, and edible in the raw state, such as apples, bananas, grapes, lemons, oranges, and strawberries. On the other hand, in botanical usage, "fruit" includes many structures that are not commonly called "fruits", such as bean pods, corn kernels, tomatoes, and wheat grains. The section of a fungus that produces spores is also called a fruiting body.

Botanic fruit and culinary fruit

Many common terms for seeds and fruit do not correspond to the botanical classifications. In culinary terminology, a fruit is usually any sweet-tasting plant part, especially a botanical fruit; a nut is any hard, oily, and shelled plant product; and a vegetable is any savory or less sweet plant product. However, in botany, a fruit is the ripened ovary or carpel that contains seeds, a nut is a type of fruit and not a seed, and a seed is a ripened ovule.

Examples of culinary "vegetables" and nuts that are botanically fruit include corn, cucurbits (e.g., cucumber, pumpkin, and squash), eggplant, legumes (beans, peanuts, and peas), sweet pepper, and tomato. In addition, some spices, such as allspice and chili pepper, are fruits, botanically speaking. In contrast, rhubarb is often referred to as a fruit, because it is used to make sweet desserts such as pies, though only the petiole (leaf stalk) of the rhubarb plant is edible, and edible gymnosperm seeds are often given fruit names, e.g., ginkgo nuts and pine nuts.

Botanically, a cereal grain, such as corn, rice, or wheat, is also a kind of fruit, termed a caryopsis. However, the fruit wall is very thin and is fused to the seed coat, so almost all of the edible grain is actually a seed.

Structure

Fruit that bears a prominent pointed terminal projection is said to be beaked.

Development

A fruit results from maturation of one or more flowers, and the gynoecium of the flower(s) forms all or part of the fruit.

Inside the ovary/ovaries are one or more ovules where the megagametophyte contains the egg cell. After double fertilization, these ovules will become seeds. The ovules are fertilized in a process that starts with pollination, which involves the movement of pollen from the stamens to the stigma of flowers. After pollination, a tube grows from the pollen through the stigma into the ovary to the ovule and two sperm are transferred from the pollen to the megagametophyte. Within the megagametophyte one of the two sperm unites with the egg, forming a zygote, and the second sperm enters the central cell forming the endosperm mother cell, which completes the double fertilization process. Later the zygote will give rise to the embryo of the seed, and the endosperm mother cell will give rise to endosperm, a nutritive tissue used by the embryo.

As the ovules develop into seeds, the ovary begins to ripen and the ovary wall, the pericarp, may become fleshy (as in berries or drupes), or form a hard outer covering (as in nuts). In some multiseeded fruits, the extent to which the flesh develops is proportional to the number of fertilized ovules. The pericarp is often differentiated into two or three distinct layers called the exocarp (outer layer, also called epicarp), mesocarp (middle layer), and endocarp (inner layer). In some fruits, especially simple fruits derived from an inferior ovary, other parts of the flower (such as the floral tube, including the petals, sepals, and stamens), fuse with the ovary and ripen with it. In other cases, the sepals, petals and/or stamens and style of the flower fall off. When such other floral parts are a significant part of the fruit, it is called an accessory fruit. Since other parts of the flower may contribute to the structure of the fruit, it is important to study flower structure to understand how a particular fruit forms.

There are three general modes of fruit development:

- Apocarpous fruits develop from a single flower having one or more separate carpels, and they are the simplest fruits.

- Syncarpous fruits develop from a single gynoecium having two or more carpels fused together.

- Multiple fruits form from many different flowers.

Plant scientists have grouped fruits into three main groups, simple fruits, aggregate fruits, and composite or multiple fruits.[15] The groupings are not evolutionarily relevant, since many diverse plant taxa may be in the same group, but reflect how the flower organs are arranged and how the fruits develop.

Simple fruit

Simple fruits can be either dry or fleshy, and result from the ripening of a simple or compound ovary in a flower with only one pistil. Dry fruits may be either dehiscent (they open to discharge seeds), or indehiscent (they do not open to discharge seeds). Types of dry, simple fruits, and examples of each, include:

- achene – most commonly seen in aggregate fruits (e.g., strawberry)

- capsule – (e.g., Brazil nut)

- caryopsis – (e.g., wheat)

- cypsela – an achene-like fruit derived from the individual florets in a capitulum (e.g., dandelion).

- fibrous drupe – (e.g., coconut, walnut)

- follicle – is formed from a single carpel, opens by one suture (e.g., milkweed), commonly seen in aggregate fruits (e.g., magnolia)

- legume – (e.g., bean, pea, peanut)

- loment – a type of indehiscent legume

- nut – (e.g., beech, hazelnut, oak acorn)

- samara – (e.g., ash, elm, maple key)

- schizocarp – (e.g., carrot seed)

- silique – (e.g., radish seed)

- silicle – (e.g., shepherd's purse)

- utricle – (e.g., strawberry)

Fruits in which part or all of the pericarp (fruit wall) is fleshy at maturity are simple fleshy fruits. Types of simple, fleshy, fruits (with examples) include:

- berry – (e.g., cranberry, gooseberry, redcurrant, tomato)

- stone fruit or drupe (e.g., apricot, cherry, olive, peach, plum)

An aggregate fruit, or etaerio, develops from a single flower with numerous simple pistils.

- Magnolia and peony, collection of follicles developing from one flower.

- Sweet gum, collection of capsules.

- Sycamore, collection of achenes.

- Teasel, collection of cypsellas

- Tuliptree, collection of samaras.

The pome fruits of the family Rosaceae, (including apples, pears, rosehips, and saskatoon berry) are a syncarpous fleshy fruit, a simple fruit, developing from a half-inferior ovary.

Schizocarp fruits form from a syncarpous ovary and do not really dehisce, but rather split into segments with one or more seeds; they include a number of different forms from a wide range of families. Carrot seed is an example.

Aggregate fruit

Aggregate fruits form from single flowers that have multiple carpels which are not joined together, i.e. each pistil contains one carpel. Each pistil forms a fruitlet, and collectively the fruitlets are called an etaerio. Four types of aggregate fruits include etaerios of achenes, follicles, drupelets, and berries. Ranunculaceae species, including Clematis and Ranunculus have an etaerio of achenes, Calotropis has an etaerio of follicles, and Rubus species like raspberry, have an etaerio of drupelets. Annona have an etaerio of berries.

The raspberry, whose pistils are termed drupelets because each is like a small drupe attached to the receptacle. In some bramble fruits (such as blackberry) the receptacle is elongated and part of the ripe fruit, making the blackberry an aggregate-accessory fruit. The strawberry is also an aggregate-accessory fruit, only one in which the seeds are contained in achenes. In all these examples, the fruit develops from a single flower with numerous pistils.

Multiple fruits

A multiple fruit is one formed from a cluster of flowers (called an inflorescence). Each flower produces a fruit, but these mature into a single mass. Examples are the pineapple, fig, mulberry, osage-orange, and breadfruit.

In the photograph on the right, stages of flowering and fruit development in the noni or Indian mulberry (Morinda citrifolia) can be observed on a single branch. First an inflorescence of white flowers called a head is produced. After fertilization, each flower develops into a drupe, and as the drupes expand, they become connate (merge) into a multiple fleshy fruit called a syncarp.

Berries

Berries are another type of fleshy fruit; they are simple fruit created from a single ovary. The ovary may be compound, with several carpels. Types include (examples follow in the table below):

- Pepo – berries whose skin is hardened, cucurbits

- Hesperidium – berries with a rind and a juicy interior, like most citrus fruit

Accessory fruit

Some or all of the edible part of accessory fruit is not generated by the ovary. Accessory fruit can be simple, aggregate, or multiple, i.e., they can include one or more pistils and other parts from the same flower, or the pistils and other parts of many flowers.

Fruit examples

Seedless fruits

Seedlessness is an important feature of some fruits of commerce. Commercial cultivars of bananas and pineapples are examples of seedless fruits. Some cultivars of citrus fruits (especially grapefruit, mandarin oranges, navel oranges), satsumas, table grapes, and watermelons are valued for their seedlessness. In some species, seedlessness is the result of parthenocarpy, where fruits set without fertilization. Parthenocarpic fruit set may or may not require pollination, but most seedless citrus fruits require a stimulus from pollination to produce fruit.

Seedless bananas and grapes are triploids, and seedlessness results from the abortion of the embryonic plant that is produced by fertilization, a phenomenon known as stenospermocarpy, which requires normal pollination and fertilization.

Seed dissemination

Variations in fruit structures largely depend on their seeds' mode of dispersal. This dispersal can be achieved by animals, explosive dehiscence, water, or wind.

Some fruits have coats covered with spikes or hooked burrs, either to prevent themselves from being eaten by animals, or to stick to the feathers, hairs, or legs of animals, using them as dispersal agents. Examples include cocklebur and unicorn plant.

The sweet flesh of many fruits is "deliberately" appealing to animals, so that the seeds held within are eaten and "unwittingly" carried away and deposited (i.e., defecated) at a distance from the parent. Likewise, the nutritious, oily kernels of nuts are appealing to rodents (such as squirrels), which hoard them in the soil to avoid starving during the winter, thus giving those seeds that remain uneaten the chance to germinate and grow into a new plant away from their parent.

Other fruits are elongated and flattened out naturally, and so become thin, like wings or helicopter blades, e.g., elm, maple, and tuliptree. This is an evolutionary mechanism to increase dispersal distance away from the parent, via wind. Other wind-dispersed fruit have tiny "parachutes", e.g., dandelion, milkweed, salsify.

Coconut fruits can float thousands of miles in the ocean to spread seeds. Some other fruits that can disperse via water are nipa palm and screw pine.

Some fruits fling seeds substantial distances (up to 100 m in sandbox tree) via explosive dehiscence or other mechanisms, e.g., impatiens and squirting cucumber.

Food uses

Many hundreds of fruits, including fleshy fruits (like apple, kiwifruit, mango, peach, pear, and watermelon) are commercially valuable as human food, eaten both fresh and as jams, marmalade and other preserves. Fruits are also used in manufactured foods (e.g., cakes, cookies, ice cream, muffins, or yogurt) or beverages, such as fruit juices (e.g., apple juice, grape juice, or orange juice) or alcoholic beverages (e.g., brandy, fruit beer, or wine).[30] Fruits are also used for gift giving, e.g., in the form of Fruit Baskets and Fruit Bouquets.

Many "vegetables" in culinary parlance are botanical fruits, including bell pepper, cucumber, eggplant, green bean, okra, pumpkin, squash, tomato, and zucchini. Olive fruit is pressed for olive oil. Spices like allspice, black pepper, paprika, and vanilla are derived from berries.

Storage

All fruits benefit from proper post harvest care, and in many fruits, the plant hormone ethylene causes ripening. Therefore, maintaining most fruits in an efficient cold chain is optimal for post harvest storage, with the aim of extending and ensuring shelf life.

Nutritional value

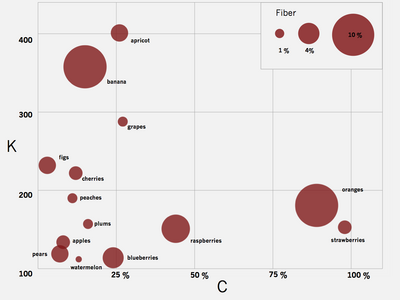

As excessive intake of added sugar is harmful and as fruits are relatively high in sugar it is often questioned whether fruits are actually healthy food. It is in fact difficult to get excessive amounts of sugar (e. g. fructose) from fruits as they also contain fibers, water and have significant chewing resistance. Studies show that fruits are very satisfying (for example apples or oranges). In addition, the fibres contained in fruits promote satiety and help lose weight and have cholesterol-lowering effects.

Regular consumption of fruit is generally associated with reduced risks of several diseases and functional declines associated with aging. A current review of meta-analyses even comes to the conclusion that current assessments might even significantly underestimate the protective associations of fruit and vegetable intakes.

Food safety

For food safety, the CDC recommends proper fruit handling and preparation to reduce the risk of food contamination and foodborne illness. Fresh fruits and vegetables should be carefully selected; at the store, they should not be damaged or bruised; and precut pieces should be refrigerated or surrounded by ice.

All fruits and vegetables should be rinsed before eating. This recommendation also applies to produce with rinds or skins that are not eaten. It should be done just before preparing or eating to avoid premature spoilage.

Fruits and vegetables should be kept separate from raw foods like meat, poultry, and seafood, as well as from utensils that have come in contact with raw foods. Fruits and vegetables that are not going to be cooked should be thrown away if they have touched raw meat, poultry, seafood, or eggs.

All cut, peeled, or cooked fruits and vegetables should be refrigerated within two hours. After a certain time, harmful bacteria may grow on them and increase the risk of foodborne illness.

Allergies

Fruit allergies make up about 10 percent of all food related allergies.

Nonfood uses

Because fruits have been such a major part of the human diet, various cultures have developed many different uses for fruits they do not depend on for food. For example:

- Bayberry fruits provide a wax often used to make candles;

- Many dry fruits are used as decorations or in dried flower arrangements (e.g., annual honesty, cotoneaster, lotus, milkweed, unicorn plant, and wheat). Ornamental trees and shrubs are often cultivated for their colorful fruits, including beautyberry, cotoneaster, holly, pyracantha, skimmia, and viburnum.

- Fruits of opium poppy are the source of opium, which contains the drugs codeine and morphine, as well as the biologically inactive chemical theabaine from which the drug oxycodone is synthesized.

- Osage orange fruits are used to repel cockroaches.

- Many fruits provide natural dyes (e.g., cherry, mulberry, sumac, and walnut).

- Dried gourds are used as bird houses, cups, decorations, dishes, musical instruments, and water jugs.

- Pumpkins are carved into Jack-o'-lanterns for Halloween.

- The spiny fruit of burdock or cocklebur inspired the invention of Velcro.

- Coir fiber from coconut shells is used for brushes, doormats, floor tiles, insulation, mattresses, sacking, and as a growing medium for container plants. The shell of the coconut fruit is used to make bird houses, bowls, cups, musical instruments, and souvenir heads.

- Fruit is often a subject of still life paintings.

Fruit flies

Fruit flies are species of flies that lay their eggs in the flesh of fruit. The pupae then consume the fruit before maturing into adult flies. Some species lay eggs in fruit that is done maturing or rotten; however, some species select hosts that are not yet ripe. Thus, these fruit flies cause significant damage to fruit crops. An example of this type of fruit fly is the Queensland fruit fly (Bactrocera tyroni) B. tyroni causes more than $28.5 million in damage to Australian fruit crops a year. Combating this pest without the use of harmful pesticides is an active area of research.