Youth International Party | |

|---|---|

| Leader | None (Pigasus used as a symbolic leader) |

| Founded | December 31, 1967 (as Yippies) |

| Headquarters | New York City |

| Newspaper | The Yipster Times Youth International Party Line Overthrow |

| Ideology | Unofficial Libertarian socialism Anarcho-communism Green anarchism Free love |

| Political position | Post-left (unofficial) |

| Colors | Black, green, red |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| yippie.mindvox.com | |

The Youth International Party (YIP), whose members were commonly called Yippies, was an American youth-oriented radical and countercultural revolutionary offshoot of the free speech and anti-war movements of the late 1960s. It was founded on December 31, 1967. They employed theatrical gestures to mock the social status quo, such as advancing a pig ("Pigasus the Immortal") as a candidate for president of the United States in 1968. They have been described as a highly theatrical, anti-authoritarian and anarchist youth movement of "symbolic politics".

Since they were well known for street theater and politically themed pranks, they were either ignored or denounced by many of the "old school" political left. According to ABC News, "The group was known for street theater pranks and was once referred to as the 'Groucho Marxists'."

Background

The Yippies had no formal membership or hierarchy. It was founded by Abbie and Anita Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Nancy Kurshan, and Paul Krassner, at a meeting in the Hoffmans' New York apartment on December 31, 1967. According to his own account, Krassner coined the name. "If the press had created 'hippie,' could not we five hatch the 'yippie'?" Abbie Hoffman wrote.

Other activists associated with the Yippies include Stew Albert, Ed Rosenthal, Allen Ginsberg, Judy Gumbo, Ed Sanders, Robin Morgan, Phil Ochs, Robert M. Ockene, William Kunstler, Jonah Raskin, Steve Conliff, Jerome Washington, John Sinclair, Dana Beal, Betty (Zaria) Andrew, Matthew Landy Steen, Joanee Freedom, Danny Boyle, Ben Masel, Tom Forcade, Paul Watson, David Peel, Wavy Gravy, Aron Kay, Tuli Kupferberg, Jill Johnston, Daisy Deadhead, Leatrice Urbanowicz, Bob Fass, Mayer Vishner, John Murdock, Alice Torbush, Judy Lampe, Walli Leff, Patrick K. Kroupa, Steve DeAngelo, Dean Tuckerman, Dennis Peron, Jim Fouratt, Steve Wessing, John Penley, Pete Wagner, and Brenton Lengel.

A Yippie flag was often seen at anti-war demonstrations. The flag had a black background with a five-pointed red star in the center, and a green cannabis leaf superimposed over it. When asked about the Yippie flag, an anonymous Yippie identified only as "Jung" told The New York Times that "The black is for anarchy. The red star is for our five point program. And the leaf is for marijuana, which is for getting ecologically stoned without polluting the environment." This flag is also mentioned in Hoffman's Steal This Book.

Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin became the most famous Yippies—and bestselling authors—in part due to publicity surrounding the five-month Chicago Seven Conspiracy trial of 1969. They both used the phrase "ideology is a brain disease" to separate the Yippies from mainstream political parties that played the game by the rules. Hoffman and Rubin were arguably the most colorful of the seven defendants accused of criminal conspiracy and inciting to riot at the August 1968 Democratic National Convention. Hoffman and Rubin used the trial as a platform for Yippie antics—at one point, they showed up in court attired in judicial robes.

Origins

The term Yippie was invented by Krassner and Hoffman on New Year's Eve 1967. Paul Krassner wrote in a January 2007 article in the Los Angeles Times:

We needed a name to signify the radicalization of hippies, and I came up with Yippie as a label for a phenomenon that already existed, an organic coalition of psychedelic hippies and political activists. In the process of cross-fertilization at antiwar demonstrations, we had come to share an awareness that there was a linear connection between putting kids in prison for smoking pot in this country and burning them to death with napalm on the other side of the planet.

Anita Hoffman liked the word, but felt that The New York Times and other "strait-laced types" needed a more formal name to take the movement seriously. That same night she came up with Youth International Party, because it symbolized the movement and made for a good play on words.

Along with the name Youth International Party, the organization was also simply called Yippie!, as in a shout for joy (with an exclamation mark to express exhilaration). "What does Yippie! mean?" Abbie Hoffman wrote. "Energy – fun – fierceness – exclamation point!"

First press conference

The Yippies held their first press conference in New York at the Americana Hotel March 17, 1968, five months before the August 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Judy Collins sang at the press conference. The Chicago Sun-Times reported it with an article titled: "Yipes! The Yippies Are Coming!"

The New Nation concept

The Yippie "New Nation" concept called for the creation of alternative, counterculture institutions: food co-ops; underground newspapers and zines; free clinics and support groups; artist collectives; potlatches, "swap-meets" and free stores; organic farming/permaculture; pirate radio, bootleg recording and public-access television; Squatting; free schools; etc. Yippies believed these cooperative institutions and a radicalized hippie culture would spread until they supplanted the existing system. Many of these ideas/practices came from other (overlapping and intermingling) counter-cultural groups such as the Diggers, the San Francisco Mime Troupe, the Merry Pranksters/Deadheads, the Hog Farm, the Rainbow Family, the Esalen Institute, the Peace and Freedom Party, the White Panther Party and The Farm. There was much overlap, social interaction and cross-pollination within these groups and the Yippies, so there was much crossover membership, as well as similar influences and intentions.

"We are a people. We are a new nation," YIP's New Nation Statement said of the burgeoning hippie movement. "We want everyone to control their own life and to care for one another ... We cannot tolerate attitudes, institutions, and machines whose purpose is the destruction of life, the accumulation of profit."

The goal was a decentralized, collective, anarchistic nation rooted in the borderless hippie counterculture and its communal ethos. Abbie Hoffman wrote:

We shall not defeat Amerika by organizing a political party. We shall do it by building a new nation—a nation as rugged as the marijuana leaf.

The flag for the "new nation" consisted of a black background with a red five pointed star in the center and a green marijuana leaf superimposed over it (same as the YIP flag).

The Chicago History Museum shows a different flag for the new nation. It is not the marijuana leaf. It has the word NOW under what looks like the all-seeing eye on a pyramid seen on the back of a dollar bill.

Culture and activism

The Yippies often paid tribute to rock 'n' roll and irreverent pop-culture figures such as the Marx Brothers, James Dean and Lenny Bruce. Many Yippies used nicknames which contained Baby Boomer television or pop references, such as Pogo or Gumby. (Pogo was notable for creating the famous slogan: "We have met the enemy and he is us"—first used on a 1970 Earth Day poster.)

The Yippies' love of pop-culture was one way to differentiate the Old and New Left, as Jesse Walker writes in Reason magazine:

Forty years ago, the yippies seemed unusual because they fused the political radicalism of the New Left with the long-haired, grass-smoking lifestyle of the counterculture. Today that combination is so familiar that many people don't even realize that the protesters and the hippies initially distrusted each other. What seems most curious about the yippies today is the way they mixed hard left politics with a deep appreciation for pop culture. Abbie Hoffman announced that he wanted to combine the styles of Andy Warhol and Fidel Castro. Jerry Rubin dedicated Do it! not just to his girlfriend but to "Dope, Color TV, and Violent Revolution." Even when praising a form of mass culture that had earned some grudging respect from the late-'60s left—rock 'n' roll—Rubin's list of musicians who "gave us the life/beat and set us free" included not just raucous originals like Jerry Lee Lewis and Bo Diddley but Fabian and Frankie Avalon, commercial confections that most lefty rock intellectuals disdained as insufficiently authentic. In one chapter, Rubin complained that if "the white ideological left" took over, "Rock dancing would be taboo, and miniskirts, Hollywood movies and comic books would be illegal." All this from a self-proclaimed communist whose heroes included Castro, Chairman Mao, and Ho Chi Minh.

It's not that the yippies swallowed pop culture uncritically. (Hoffman kept a sign attached to the bottom of his TV that said "bullshit.") It's that they saw the mass media's dream-world as another terrain to fight in.

At demonstrations and parades, Yippies often wore face paint or colorful bandannas to keep from being identified in photographs. Other Yippies reveled in the spotlight, allowing their stealthier comrades the anonymity they needed for their pranks.

One cultural intervention that misfired was at Woodstock, with Abbie Hoffman interrupting a performance by The Who, trying to speak against the incarceration of John Sinclair, sentenced to 10 years in prison in 1969 after giving two joints to an undercover narcotics officer. Guitarist Pete Townshend used his guitar to bat Hoffman off the stage.

The Yippies were the first on the New Left to make a point of exploiting mass media. Colorful, theatrical Yippie actions were tailored to attract media coverage and also to provide a stage where people could express the "repressed" Yippie inside them. "We believe every nonyippie is a repressed yippie," Jerry Rubin wrote in Do it! "We try to bring out the yippie in everybody."

Early Yippie actions

Yippies were famous for their sense of humor. Many direct actions were often satirical and elaborate pranks or put-ons. An application to levitate The Pentagon during the October, 1967 March on the Pentagon, and a mass protest/mock levitation at the building organized by Rubin, Hoffman and company at the event, helped to set the tone for Yippie when it was established a couple of months later.

Another famous prank just before Yippie was coined was a guerrilla theater event in New York City on August 24, 1967. Abbie Hoffman and a group of future Yippies managed to get into a tour of the New York Stock Exchange, where they threw fistfuls of real and fake US$ from the balcony of the visitors' gallery down to the traders below, some of whom booed, while others began to scramble frantically to grab the money as fast as they could. The visitors' gallery was closed until a glass barrier could be installed, to prevent similar incidents.

On the 40th anniversary of the NYSE event, CNN Money editor James Ledbetter described the now-famous incident:

[The] group of pranksters began throwing handfuls of one-dollar bills over the railing, laughing the entire time. (The exact number of bills is a matter of dispute; Hoffman later wrote that it was 300, while others said no more than 30 or 40 were thrown.)

Some of the brokers, clerks and stock runners below laughed and waved; others jeered angrily and shook their fists. The bills barely had time to land on the ground before guards began removing the group from the building, but news photos had been taken and the Stock Exchange "happening" quickly slid into iconic status.

Once outside, the activists formed a circle, holding hands and chanting "Free! Free!" At one point, Hoffman stood in the center of the circle and lit the edge of a $5 bill while grinning madly, but an NYSE runner grabbed it from him, stamped on it, and said: "You're disgusting."

If the prank accomplished nothing else, it helped cement Hoffman's reputation as one of America's most outlandish and creative protestors ... the "Yippie" movement quickly became a prominent part of America's counterculture.

There was a clash with police on March 22, 1968, where a large group of countercultural youths led by the Yippies descended into Grand Central Station for a "Yip-In". The night erupted into a violent clash with police that Don McNeill of The Village Voice called a "pointless confrontation in a box canyon". A month later, Yippies organized a "Yip-Out," a be-in style event in Central Park that went off peacefully and drew 20,000 people.

In his book A Trumpet to Arms: Alternative Media in America, author David Armstrong points out that the Yippie hybrid of performance art, Guerilla theatre and political irreverence was often in direct conflict with the sensibility of the 60s American Left/peace movement:

The Yippies' unorthodox approach to revolution, which emphasized spontaneity over structure, and media blitz over community organizing, put them almost as much at odds with the rest of the left as with mainstream culture. Wrote (Jerry) Rubin in the Berkeley Barb, "The worst thing you can say about a demonstration is that it is boring, and one of the reasons that the peace movement has not grown into a mass movement is that the peace movement—its literature and its events—is a bore. Good theatre is needed to communicate revolutionary content.

House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) subpoenaed Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman of the Yippies in 1967, and again in the aftermath of the 1968 Democratic National Convention. The Yippies used media attention to make a mockery of the proceedings: Rubin came to one session dressed as an American Revolutionary War soldier, and passed out copies of the United States Declaration of Independence to people in attendance. Then Rubin "blew giant gum bubbles while his co-witnesses taunted the committee with Nazi salutes". Rubin also attended HUAC dressed as Santa Claus and a Viet Cong soldier.

On another occasion, police stopped Hoffman at the building entrance and arrested him for wearing an American flag. Hoffman quipped for the press, "I regret that I have but one shirt to give for my country", paraphrasing the last words of revolutionary patriot Nathan Hale; meanwhile Rubin, who was wearing a matching Viet Cong flag, shouted that the police were Communists for not arresting him also.

According to The Harvard Crimson:

In the fifties, the most effective sanction was terror. Almost any publicity from HUAC meant the 'blacklist.' Without a chance to clear his name, a witness would suddenly find himself without friends and without a job. But it is not easy to see how in 1969 a HUAC blacklist could terrorize an SDS activist. Witnesses like Jerry Rubin have openly boasted of their contempt for American institutions. A subpoena from HUAC would be unlikely to scandalize Abbie Hoffman or his friends.

Chicago '68

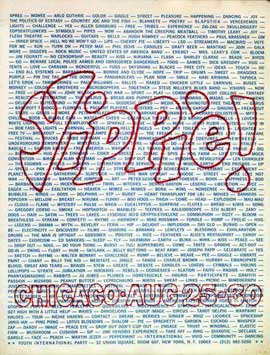

Yippie theatrics culminated at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. YIP planned a six-day Festival of Life – a celebration of the counterculture and a protest against the state of the nation. This was supposed to counter the "Convention of Death." This promised to be "the blending of pot and politics into a political grass leaves movement – a cross-fertilization of the hippie and New Left philosophies." Yippies' sensational statements before the convention were part of the theatrics, including a tongue-in-cheek threat to put LSD in Chicago's water supply. "We will fuck on the beaches! ... We demand the Politics of Ecstasy! ... Abandon the Creeping Meatball! ... And all the time 'Yippie! Chicago – August 25–30.'" First on a list of Yippie demands: "An immediate end to the war in Vietnam."

Yippie organizers hoped that well-known musicians would participate in the Festival of Life and draw a crowd of tens if not hundreds of thousands from across the country. The city of Chicago refused to issue any permits for the festival and most musicians withdrew from the project. Of the rock bands who had agreed to perform, only the MC5 came to Chicago to play and their set was cut short by a clash between the audience of a couple thousand and police. Phil Ochs and several other singer-songwriters also performed during the festival.

In response to the Festival of Life and other anti-war demonstrations during the Democratic convention, Chicago police repeatedly clashed with protesters, as many millions of viewers watched the extensive TV coverage of the events. On the evening of August 28 the police attacked the protesters in front of the Conrad Hilton hotel as the demonstrators chanted "The whole world is watching". This was a "police riot," concluded the US National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence, stating:

"On the part of the police there was enough wild club swinging, enough cries of hatred, enough gratuitous beating to make the conclusion inescapable that individual policemen, and lots of them, committed violent acts far in excess of the requisite force for crowd dispersal or arrest."

The conspiracy trial

Following the convention, eight protesters were charged with conspiracy to incite the riots. Their trial, which lasted five months, was heavily publicized. The Chicago Seven represented a cross-section of the New Left, including Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin.

In his book, American Fun: Four Centuries of Joyous Revolt, John Beckman writes:

Never mind Hair, the so-called Chicago Eight (then Seven) trial was the countercultural performance of the sixties. Guerrilla theater stared down courtroom farce to decide the civil dispute of the era: the Movement vs. the Establishment. The eight defendants seemed finically chosen to represent the world of dissent: SDS leaders Rennie Davis and Tom Hayden (who had authored "The Port Huron Statement"); graduate students Lee Weiner and John Froines; portly fifty-four-year-old Christian socialist David Dellinger; Yippies Rubin and Hoffman; and—briefly--Black Panther Bobby Seale. "Conspire, hell," Hoffman quipped. "We couldn't agree on lunch."

Several other Yippies – including Stew Albert, Wolfe Lowenthal, Brad Fox and Robin Palmer – were among another 18 activists named as "unindicted co-conspirators" in the case. While five of the defendants were initially convicted of crossing state lines to incite a riot, all convictions were soon reversed in appeal court. Defendants Hoffman and Rubin became popular authors and public speakers, spreading Yippie militancy and comedy wherever they appeared. When Hoffman appeared on The Merv Griffin Show, for example, he wore a shirt with an American flag design, prompting CBS to black out his image when the show aired.

The Yippie movement

The Youth International Party quickly spread beyond Rubin, Hoffman and the other founders. YIP had chapters all over the US and in other countries, with particularly active groups in New York City, Vancouver, Washington, D.C., Detroit, Milwaukee, Los Angeles, Tucson, Houston, Austin, Columbus, Dayton, Chicago, Berkeley, San Francisco and Madison. There were YIP conferences through the 1970s, beginning with a "New Nation Conference" in Madison, Wisconsin in 1971.

On the final day of the Madison conference, April 4, 1971, hundreds of riot police broke up a block party organized by local Yippies to cap the event, resulting in a street clash between Yippies and police.

Street protests

During an anti-war protest in Washington, D.C., on November 15, 1969, East Coast Yippies led thousands of youths in the storming of the Justice Department building.

On August 6, 1970, L.A. Yippies invaded Disneyland, hoisting the New Nation flag at City Hall and taking over Tom Sawyer's Island. While riot police confronted the Yippies, the theme park was closed early for only the second time in the park's history (the first being shortly after the assassination of President Kennedy.). As many as 23 of the 200 Yippies attending were arrested.

Vancouver Yippies invaded the US border town of Blaine, Washington, on May 9, 1970, to protest Richard Nixon's invasion of Cambodia and the shooting of students at Kent State.[116]

Columbus Yippies were charged with inciting the rioting that occurred in the city on May 11, 1972, in response to Nixon's mining of North Vietnam's Haiphong harbor.[117] They were acquitted.

YIP was a member of the coalition of anti-Vietnam War activists who, over several days in early May 1971, tried to shut down the US government by occupying intersections and bridges in Washington, D.C. The May Day protests resulted in the largest mass arrest in American history.

A frequent 'national' complaint among Yippies was that the New York 'central HQ' chapter acted as if other chapters did not exist and kept them out of the decision-making process. At one point, at a YIP conference in Ohio in 1972, Yippies voted to 'exclude' Abbie and Jerry as official spokespersons from the party, since they had become too famous and rich.

In 1972, Yippies and Zippies (a younger YIP radical breakaway faction whose "guiding spirit" was Tom Forcade) staged protests at the Republican and Democratic Conventions in Miami Beach. Some of the Miami protests were larger and more militant than the ones in Chicago in 1968. After Miami, the Zippies evolved back into Yippies.

In 1973, Yippies marched on the Manhattan home of Watergate conspirator John Mitchell:

... five hundred die-hard Yippies staged one last march on the Mitchell home, no longer the Watergate but a grand apartment building on Manhattan's Fifth Avenue. "Free Martha Mitchell!" they chanted. "Fuck John!" When the Mitchells finally appeared at the window to see what all the commotion was about, the stoners cherished their last "eye-to-eyeball confrontation with Mr. Law 'n' Order." To commemorate the moment, they placed a giant marijuana joint on the Mitchells' doorstep.

Yippies regularly protested at US presidential inaugurations, with a particularly strong presence at the 1973 inauguration of Richard Nixon. Yippies also demonstrated at the 1980 Republican National Convention in Detroit, as well as the subsequent 1984 Republican National Convention in Dallas, where 99 Yippies were arrested:

DALLAS, Aug 22 — Ninety-nine demonstrators were arrested today outside the Republican National Convention after a Corporate War Chest Tour through the downtown area in which they intimidated shoppers, splattered paint and burned an American flag. The demonstrators, members of the Youth International Party, or Yippies, completed the spree through downtown by jumping into the reflecting pool at City Hall in the sweltering Dallas heat.

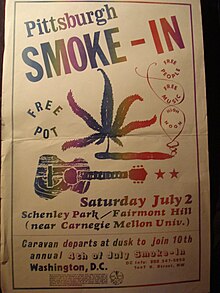

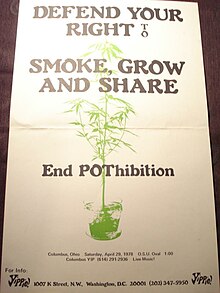

Smoke-ins

Yippies organized marijuana "smoke-ins" across North America through the 1970s and into the 1980s. The first YIP smoke-in was attended by 25,000 in Washington, D.C. on July 4, 1970. There was a culture clash when many of the hippie protesters strolled en masse into the nearby "Honor America Day" festivities with Billy Graham and Bob Hope.

On August 7, 1971, a Yippie smoke-in in Vancouver was attacked by police, resulting in the Gastown Riot, one of the most famous protests in Canadian history.

The annual July 4 Yippie smoke-in in Washington, D.C., became a counterculture tradition.

Alternative culture

Yippies organized alternative institutions in their counterculture communities. In Tucson, Yippies operated a free store; in Vancouver, Yippies established the People's Defense Fund to provide legal help for the often-harassed hippie community; in Milwaukee, Yippies helped launch the city's first food co-op.

Many Yippies were involved in the underground press. Some were the editors of major underground newspapers or alternative magazines, including Yippies Abe Peck (Chicago Seed), Jeff Shero Nightbyrd (New York's Rat and Austin Sun), Paul Krassner (The Realist), Robin Morgan (Ms. magazine), Steve Conliff (Purple Berries, Sour Grapes and Columbus Free Press), Bob Mercer (The Georgia Straight and Yellow Journal), Henry Weissborn (ULTRA), James Retherford (The Rag), Mayer Vishner (LA Weekly), Matthew Landy Steen and Stew Albert (Berkeley Barb and Berkeley Tribe), Tom Forcade (Underground Press Syndicate and High Times) and Gabrielle Schang (Alternative Media). New York Yippie Coca Crystal hosted the popular cable TV program If I Can't Dance You Can Keep Your Revolution.

Yippies were active in alternative music and movies. Singer-songwriters Phil Ochs and David Peel were Yippies. "I helped design the party, formulate the idea of what Yippie was going to be, in the early part of 1968," Ochs testified at the Chicago Eight trial.

The strange, legendary cult film Medicine Ball Caravan (partly financed by Tom Forcade), chronicled Yippie drop-outs and a variety of other fascinating and dynamic characters of the era. The movie title was later controversially changed to "We Have Come for your Daughters".

Radical musicians usually found enthusiastic audiences at Yippie-sponsored events and frequently offered to play. YIP-affiliated John Sinclair managed Detroit's proto-punk band the MC5, who played in Lincoln Park during protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. In 1970, Pete Seeger played a Vancouver Yippie rally against construction of a highway through Jericho Beach Park. The first-ever concert by the influential and iconic proto-punk band the New York Dolls, was a Yippie benefit to raise funds to pay legal fees for one of Dana Beal's marijuana arrests in the 1970s.

The Youth International Party founded the US branch of the Rock Against Racism movement in 1979. Rock Against Racism USA later morphed into the critically acclaimed, Yippie-organized, widely recognized national Rock Against Reagan tour in 1983. Well-known bands on the tour included Michelle Shocked, the Dead Kennedys, the Crucifucks, MDC, Cause for Alarm, Toxic Reasons and Static Disruptors. A young Whoopi Goldberg performed stand-up comedy (as did Will Durst) at the San Francisco R-A-R show.

Vancouver Yippies Ken Lester and David Spaner were the managers of Canada's two most notorious political punk bands, D.O.A. (Lester) and The Subhumans (Spaner). New York Yippie/High Times publisher Tom Forcade financed one of the first movies about punk rock, D.O.A., featuring footage of the Sex Pistols' 1978 tour of America.

Infamous Baltimore Yippie John Waters became a renowned independent filmmaker (Pink Flamingos, Polyester, Hairspray), once claiming in an interview that the Yippies influenced his irreverent sense of style: "I was a Yippie agitator, and I wanted to look like Little Richard. I dressed like a hippie pimp back then, because punk wasn't around yet.

Pranking the system

Yippies mocked the system and its authority. The Youth International Party, having nominated a pig (Pigasus) for US president in 1968, famously ran Nobody for President as its 'official' candidate in 1976.

Vancouver Yippie Betty "Zaria" Andrew ran as the Youth International Party's candidate for mayor in 1970. One of her campaign promises was to repeal every law, including the law of gravity so that everyone could get high. That same year, Berkeley Yippie Stew Albert ran for sheriff of Alameda County, challenging the incumbent sheriff to a high-noon duel and receiving 65,000 votes.

In 1970, Detroit Yippies went to city hall and applied for a permit to blow up the General Motors building. After the permit was denied, the Yippies said that it just goes to show you can't work within the system to change the system. "This destroys my last hope for legal channels," said Detroit Yippie Jumpin' Jack Flash.

Some Yippies, including Robin Morgan, Nancy Kurshan, Sharon Krebs and Judy Gumbo, were active in the Guerilla theatre feminist group W.I.T.C.H. (Women's International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell), which combined "theatricality, humor, and activism."

On November 7, 1970, Jerry Rubin and London Yippies took over The Frost Programme when he was the guest on the popular British host's TV program. In all the chaos, a Yippie fired a water pistol into host David Frost's open mouth, the broadcaster called for a commercial break and the show was over. The Daily Mirror's banner headline: "THE FROST FREAKOUT."

Pie-throwing

Pie-throwing as a political act was invented by Yippies. The first political pieing was carried out by Tom Forcade, when he pied a member of the President's Commission on Obscenity and Pornography in 1970. Milwaukee Yippie Pat Small was the first person to be arrested for a pieing, following a hit on a Miami alderman prior to the convention protests in 1972. Columbus Yippie Steve Conliff pied Ohio Governor James Rhodes in 1977 to protest the Kent State shootings.

Aron "The Pieman" Kay became the best-known Yippie pie-thrower. Kay's many targets included Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, New York City Mayor Abe Beame, conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly, Watergate burglar Frank Sturgis, ex-CIA head William Colby, National Review publisher/editor William F. Buckley, and notorious Studio 54 disco-owner and tax-evader, Steve Rubell. Kay's flamboyant 1979 attempt to pie Elvis Costello (for racist comments made to Bonnie Bramlett and Stephen Stills in a Columbus, Ohio Holiday Inn bar, earlier that year) was thwarted by security at the Manhattan punk nightclub Great Gildersleeves.

Nobody for President and "None of the Above"

Perhaps one of the swan songs of Yippies was a groundbreaking effort to place a new voting option, None of the Above, on the election ballot in Santa Barbara County, in California, by the Isla Vista Municipal Advisory Council in 1976. This represented an incipient libertarian impulse of Yippies and the first example in the United States of this election ballot alternative, in what one of the resolution's two co-sponsors, Matthew Steen, described as an "anti-institutional Yippie up-yours." Years earlier Steen had been a Yippie activist with Stew Albert, as a reporter with the Berkeley Tribe. This novel motion was adopted unanimously by the Council, having a ripple effect across the country, with voters in Nevada approving this option in a change to state election laws in 1986. And in 2000 a citizen initiative to place None of the Above on the official state ballot in California was qualified although the proposition was voted down 62% to 38% in the general election that year. The most recent addition, internationally, are for state elections in India where this option must be made available in electronic voting machines.

In 1976, national Yippies took a cue from Isla Vistans, backing Nobody for President, a campaign that took on a life of its own in the post-Watergate malaise of the mid-70s. The Yippie campaign slogan: "Nobody's perfect." (Meanwhile, in a strange twist of Yippie fate, Matthew Steen had become treasurer of a student-led campaign to elect Jerry Brown for President, competing against both "Nobody for President" and Jimmy Carter during the presidential primary campaign of that year.)

From the experimental combination of Isla Vista local politics, presidential campaigns and the Yippies, the name and spirit of this unexpected ballot initiative spread quickly—in the form of None of the Above music festivals, radio and television shows, rock bands, T-shirts, buttons, (decades later) countless websites and other related social phenomena. The die-hard dedication to the 'option' of Nobody for President and None of the Above has not abated since the counter-cultural 70s, but has only grown, unexpectedly taking the Yippie legacy into a new century and succeeding generations.

Writings

"An exegesis on women's liberation" by the Women's Caucus within the Youth International Party was included in the 1970 anthology Sisterhood is Powerful: An Anthology of Writings From The Women's Liberation Movement, edited by Robin Morgan.

In June 1971 Abbie Hoffman and Al Bell started the pioneer phreak magazine The Youth International Party Line (YIPL). Later, the name was changed to TAP for Technological American Party or Technological Assistance Program.

Milwaukee Yippies published Street Sheet, the first of the anarchist zines later to become so popular in many cities. The Open Road, an internationally known journal of the anti-authoritarian left, was founded by a core of Vancouver Yippies.

The semi-official Yippie house organ, The Yipster Times, was founded by Dana Beal in 1972 and published in New York City; the name was changed to Overthrow in 1979.

The mercurial Yippie-turned-Zippie Tom Forcade founded the very-successful High Times magazine in 1974. So many writers for Yipster Times would go on to write for High Times, it was often referred to as the farm team.

The most famous writing to come out of the Yippie movement is Abbie Hoffman's Steal This Book, which is considered to be a guidebook in causing general mischief and capturing the spirit of the Yippie movement. Hoffman is also the author of Revolution for the Hell of It which has been called the original Yippie book. This book claims that there were no actual yippies, and that the name was just a term used to create a myth.

Jerry Rubin published his account of the Yippie movement in his book Do IT!: Scenarios of Revolution.

Books on Yippie by Yippies include Woodstock Nation and Soon to Be a Major Motion Picture (Abbie Hoffman), We Are Everywhere (Jerry Rubin), Trashing (Anita Hoffman), Who the Hell is Stew Albert? (Stew Albert), Confessions of a Raving, Unconfined Nut (Paul Krassner) and Shards of God: A Novel of the Yippies (Ed Sanders). Some other books about that era: Woodstock Census: The Nationwide Survey of the Sixties Generation (Deanne Stillman and Rex Weiner), The Panama Hat Trail (Tom Miller),[233][234]Can't Find My Way Home: America in the Great Stoned Age, 1945-2000 (Martin Torgoff), Groove Tube: Sixties Television and the Youth Rebellion (Aniko Bodroghkozy), and The Ballad of Ken and Emily: or, Tales from the Counterculture (Ken Wachsberger).

Buy This Book, written and illustrated by political cartoonist and post-'60s Yippie activist Pete Wagner, who distributed copies of the Yipster Times on the University of Minnesota campus in the mid-1970s, was promoted by Hoffman, who said the book "manages to reach to the limits of bad taste." Buy This Too recounts efforts by a guerrilla street theater gang named the 1985 Brain Trust to "fight the New Right with Yippie-like myth-making tactics." The Brain Trust was inspired by a series of meetings and interviews between Wagner and Paul Krassner in Minneapolis during May 1981, as Krassner performed stand-up comedy at Dudley Riggs ETC Theater.

In 1983, a group of Yippies published Blacklisted News: Secret Histories from Chicago, '68 to 1984 (Bleecker Publishing), a large, 'phone-book sized anthology' (733 pages) of Yippie history, including journalistic accounts from both alternative and mainstream media, as well as many personal stories and essays. Includes countless photographs, old leaflets and posters, 'underground' comics, newspaper clippings, and various other historical ephemera. The editors (often doubling as authors) officially called themselves "The New Yippie Book Collective"; which included Steve Conliff (who wrote over half the volume), Dana Beal (head archivist), Grace Nichols, Daisy Deadhead, Ben Masel, Alice Torbush, Karen Wachsman, and Aron Kay. It is still in print.

Vancouver Yippie Bob Sarti's play Yippies in Love, premiered in June 2011.

2000s

In 2000, a Hollywood film based on the life of Yippie co-founder Abbie Hoffman, titled Steal This Movie (spoofing the title of his book, Steal This Book), was released to mixed reviews, with Vincent D'Onofrio in the title role. Noted film critic Roger Ebert gave the movie a positive review, remarking that although it is often difficult to credibly bring historic events to life, he believed the movie succeeded:

Abbie Hoffman is seen wearing an American flag shirt and getting in trouble for desecrating it; the movie cuts to footage of Roy Rogers and Dale Evans yodeling while wearing their flag shirts. Hoffman insisted that the flag represented all Americans, including those opposed to the war; he resisted efforts of the Right to annex it as their exclusive ideological banner.

Vincent D'Onofrio has an interesting task, playing the role, since Hoffman seems on autopilot much of the time. He is charismatic and has an instinctive grasp of the dramatic gesture, but can be infuriating on a one-to-one level ...

The Yippies continued as a small movement into the early 2000s. The New York chapter was known for their annual marches for decades in New York City to legalize marijuana; NYC Yippie Dana Beal started the Global Marijuana March in 1999. Beal also continued to crusade for the use of Ibogaine to treat heroin addicts. Another Yippie, A.J. Weberman, continued the deconstruction of the poetry of Bob Dylan and speculation about tramps on the Grassy Knoll through various websites. Weberman has for a long time been active in the Jewish Defense Organization.

Throughout this decade, NYC Yippies frequently joined in local anti-gentrification protests over the continuing transformation of New York's Lower East Side.

In 2008, there was a very public feud between A.J. Weberman and fellow founding-Yippie, popular New York radio host Bob Fass of WBAI. The incidents around this feud briefly brought increased local attention to Yippies, particularly since this occurred around the same time a new PBS movie about the Chicago riots was getting widespread national attention. The film featured Hank Azaria as Abbie Hoffman and Mark Ruffalo as Jerry Rubin, touching off a new generation's interest, since both are now deceased.

In 1989, Abbie Hoffman, who had been suffering intermittent bouts of depression, committed suicide with alcohol and about 150 phenobarbital pills. By contrast, Jerry Rubin became a fast-talking (and by all accounts, fairly successful) stockbroker and showed no regrets. In 1994 he was fatally injured by a car while jaywalking. By the age of 50, Rubin had broken with many of his previous countercultural views; he was interviewed by The New York Times, which described him as a "yippie-turned-conspicuous-yuppie." In the interview, he stated that "Until me, nobody had really taken off their clothes and screamed out loud, 'It's O.K. to make money!'"

Yippie museum and cafe

In 2004, the Yippies, along with the National AIDS Brigade, purchased the long-time Yippie "headquarters" (which had initially been acquired by squatting) at 9 Bleecker Street in New York City for $1.2 million. After official purchase, it was converted into the "Yippie Museum/Café and Gift Shop", housing a multitude of counter-cultural and leftist memorabilia from all over the world, as well as providing an independently operated café that featured live music on scheduled nights. Performers at the café included both nationally known figures and local bands, including Roseanne Barr, Ed Rosenthal, The Fiction Circus, and Joel Landy. The museum was chartered by the Board of Regents of the University of the State of New York.

According to the original curator's message, the museum was founded "to preserve the history of the Youth International Party and all of its offshoots." The Board of Directors: Dana Beal, Aron Kay, David Peel, William Propp, Paul DeRienzo, and A. J. Weberman.

George Martinez was a semi-frequent speaker at the Yippies' Open-Mic, known as "Occupational Hazards/The People's Soapbox," as was Andy Stepanian and Captain Ray Lewis.

In Summer 2013, The Yippie Cafe officially closed. At the beginning of 2014, the Yippie building (Museum) at #9 Bleecker was sold, closed and permanently cleaned out; most of the memorabilia and historic materials dispersed among the remaining New York Yippies.

As of 2017, the old Yippie building at #9 Bleecker had been totally transformed into a successful Bowery-area Boxing club called "Overthrow", deliberately and artfully retaining much of its original Yippie/60s-revolutionary decor. Tourists still drop by to see it.