Reporters Sans Frontières | |

| |

| Formation | 1985 |

|---|---|

| Founder | Robert Ménard, Rémy Loury, Jacques Molénat and Émilien Jubineau |

| Type | Nonprofit organization, non-governmental organization with consultant status at the United Nations |

| Headquarters | Paris, France |

Director General | Christophe Deloire (since July 2012) |

Key people | Christophe Deloire, Secretary General Pierre Haski, President RSF France Mickael Rediske, President RSF Germany Christian Mihr, CEO RSF Germany Rubina Möhring, President RSF Austria Alfonso Armada, President RSF Spain Gérard Tschopp, President RSF Switzerland Erik Halkjær, President, RSF Sweden Jarmo Mäkelä, President, RSF Finland |

Budget | €6 million (RSF France) |

Staff | Approximately 100 |

| Website | rsf |

Reporters Without Borders (French: Reporters sans frontières (RSF)) is an international non-profit and non-governmental organization that safeguards the right to freedom of information. Its advocacy is founded on the belief that everyone requires access to the news and information, inspired by Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that recognizes the right to receive and share information regardless of frontiers, along with other international rights charters. RSF has consultative status at the United Nations, UNESCO, the Council of Europe, and the International Organisation of the Francophonie.

Activities

RSF works on the ground in defence of individual journalists at risk and also at the highest levels of government and international forums to defend the right to freedom of expression and information. It provides daily briefings and press releases on threats to media freedom in French, English, Spanish, Portuguese, Arabic, Farsi and Chinese and publishes an annual press freedom round up, the World Press Freedom Index, that measures the state of media freedom in 180 countries. The organization provides assistance to journalists at risk and training in digital and physical security, as well as campaigning to raise public awareness of abuse against journalists and to secure their safety and liberty. RSF lobbies governments and international bodies to adopt standards and legislation in support of media freedom and takes legal action in defence of journalists under threat.

To mark World Day Against Cyber-Censorship on 12 March, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) has unveiled a list of 20 Digital Predators of Press Freedom and announces that it is now unblocking access to a total 21 websites in the sixth year of its Operation Collateral Freedom.

History

RSF was founded in Montpellier, France in 1985 by Robert Ménard, Rémy Loury, Jacques Molénat and Émilien Jubineau. It was registered as a non-profit organization in 1995. Ménard was RSF's first secretary general, succeeded by Jean-Francois Juillard. Christophe Deloire was appointed secretary-general in 2012.

Structure

RSF's head office is based in Paris. It has 13 regional and national offices, including Brussels, London, Washington, Berlin, Rio de Janeiro and Dakar, and a network of 146 correspondents. It employs 57 salaried staff in Paris and internationally. A board of governors, elected from RSF's members, approves the organization's policies. An International Council has oversight of the organization's activities and approves the accounts and budget.

Advocacy

World Press Freedom Index

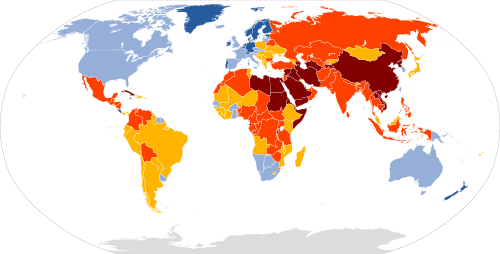

| Very serious situation Difficult situation | Noticeable problems Satisfactory situation | Good situation Not classified / No data |

Information and Democracy Initiative

In 2018, RSF launched the Information and Democracy Commission to introduce new guarantees for freedom of opinion and expression in the global space of information and communication. In a joint mission statement, the Commission's presidents, RSF secretary-general Christophe Deloire and Nobel laureate Shirin Ebadi identified a range of factors currently threatening that freedom. This includes: political control of the media, subjugation of news and information to private interests, the growing influence of corporate actors, online mass disinformation and the erosion of quality journalism.

This Commission published the International Declaration on Information and Democracy to state principles, define objectives and propose forms of governance for the global online space for information and communication. The Declaration emphasised that corporate entities with a structural function in the global space have duties, especially as regards political and ideological neutrality, pluralism and accountability. It called for recognition of the right to information that is diverse, independent and reliable in order to form opinions freely and participate fully in the democratic debate.

At the Paris Peace Forum in 2018, 12 countries launched a political process aimed at providing democratic guarantees for news and information and freedom of opinion, based on the principles set out in the Declaration.

Journalism Trust Initiative

RSF launched the Journalism Trust Initiative (JTI) in 2018 with its partners the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), Agence France Presse (AFP) and the Global Editors Network (GEN). JTI defines indicators for trustworthy journalism and rewards compliance, bringing tangible benefits for all media outlets and supporting them in creating a healthy space for information. JTI distinguishes itself from similar initiatives by focusing on the process of journalism rather than content alone. Media outlets will be expected to comply with standards that include transparency of ownership, sources of revenue and proof of a range of professional safeguards.

Actions

RSF's defence of journalistic freedom includes international missions, the publication of country reports, training of journalists and public protests. Recent global advocacy and practical interventions have included: opening a centre for women journalists in Afghanistan in 2017, a creative protest with street-artist C215 in Strasbourg for Turkish journalists in detention, turning off the Eiffel Tower lights in tribute to murdered Saudi journalist Jamal Kashoggi and providing training to journalists and bloggers in Syria. In July 2018, RSF made an unprecedented mission to Saudi Arabia calling for the release of 30 journalists. The organization publishes a gallery of Predators of Press Freedom, highlighting the most egregious international violators of press freedom. It also maintains an online Press Freedom Barometer, monitoring the number of journalists, media workers and citizen journalists killed or imprisoned. Its programme Operation Collateral Freedom, launched in 2014, provides alternative access to censored websites by creating mirror sites: 22 sites have been unblocked in 12 countries, including Iran, China, Saudi Arabia and Vietnam. RSF offers grants to journalists at risk and supports media workers in need of refuge and protection.

Prizes

RSF's annual Press Freedom Prize, created in 1992, honours courageous and independent journalists who have faced threats or imprisonment for their work and who have challenged the abuse of power. TV5-Monde is a partner in the prize.

A Netizen Prize was introduced in 2010, in partnership with Google, recognizing individuals, including bloggers and cyber-dissidents, who have advanced freedom of information online through investigative reporting or other initiatives.

In 2018, RSF launched new categories for the Press Freedom Prize: courage, independence and impact.

Press Freedom Prizewinners 1992-2019

- 1992 Zlatko Dizdarevic, Bosnia-Herzegovina

- 1993 Wang Juntao, China

- 1994 André Sibomana, Rwanda

- 1995 Christina Anyanwu, Nigeria

- 1996 Isik Yurtçu, Turkey

- 1997 Raúl Rivero, Cuba

- 1998 Nizar Nayyouf, Syria

- 1999 San San Nweh, Burma

- 2000 Carmen Gurruchaga, Spain

- 2001 Reza Alijani, Iran

- 2002 Grigory Pasko, Russia

- 2003 Ali Lmrabet, Morocco; The Daily News, Zimbabwe; Michèle Montas, Haiti

- 2004 Hafnaoui Ghoul, Algeria; Zeta, Mexico; Liu Xiaobo, China

- 2005 Zhao Yan, China; Tolo TV, Afghanistan; National Union of Somalian Journalists, Somalia; Massoud Hamid, Syria

- 2006 Win Tin, Burma; Novaya Gazeta, Russia; Guillermo Fariñas Hernández, Cuba

- 2007 Seyoum Tsehaye, Eritrea; Democratic Voice of Burma, Burma; Kareem Amer, Egypt; Hu Jia, Zeng Jinyan, China

- 2008 Ricardo Gonzales Alfonso, Cuba; Radio Free NK, North Korea; Zarganar and Nay Phone Latt, Burma

- 2009 Amira Hass, Israel; Dosh, Chechnya

- 2010 Abdolreza Tajik, Iran; Radio Shabelle, Somalia

- 2011 Ali Ferzat, Syria; Weekly Eleven News, Burma

- 2012 Mazen Darwish, Syria; 8Sobh, Afghanistan

- 2013 Muhammad Bekjanov, Uzbekistan; Uthayan, Sri Lanka

- 2014 Sanjuana Martínez, Mexico; FrontPage Africa, Liberia; Raif Badawi, Saudi Arabia

- 2015 Zeina Erhaim, Syria; Zone9, Ethiopia; Cumhuriyet, Turkey

- 2016 Hadi Abdullah, Syria; 64 Tianwang, China; Lu Yuyu and Li Tingyu, China

- 2017 Tomasz Piatek, Poland; Medyascope, Turkey; Soheil Arabi, Iran

- 2018 Swati Chaturvedi, India; Matthew Caruana Galizia, Malta; Inday Espina-Varona; Philippines; Carole Cadwalladr, United Kingdom

- 2019 Eman al Nafjan, Saudi Arabia; Pham Doan Trang, Vietnam; Caroline Muscat, Malta

Netizen Prize

- 2010 Change for Equality website, www.we-change.org, women's rights activists, Iran

- 2011: Nawaat.org, bloggers, Tunisia

- 2012: Local Coordination Committees of Syria, media centre, citizen journalists and activists, Syria

- 2013: Huynh Ngoc Chenh, blogger, Vietnam

- 2014: Raif Badawi, blogger, Saudi Arabia

- 2015: Zone9, blogger collective, Ethiopia

- 2016: Lu Yuyu and Li Tingyu, citizen journalists, China

Annual reports

Report 2012

Reporters Without Borders, in its comprehensive statistical report released on Wednesday, December 19, 2012, called 2012 the "deadliest year" for journalists compared to previous years. According to the report, 67 journalists were killed or killed in 2012, while 879 were arrested and 38 were abducted. In this report, Iran is called one of the largest prisons in the world for journalists.

Report 2013

The 2013 World Press Freedom Index was published on 30 January 2013 and intends to reflect the situation of The Relatives held hostage in Iran. Iran rises one place and exceeds to (174th). The report emphasized that in Iran the print and broadcast media and news websites are all controlled by the Ministry of Intelligence and the Revolutionary Guards. The Iranian authorities have internationalized their repression by making hostages out of the relatives of Iranian journalists who work abroad or in Iran for foreign news media. The Islamic Republic of Iran is one of the world's five biggest prisons for news and information providers.

Report 2014

According to the Reporters without Borders (RSF) on the 2014 annual report, the number of journalists killed worldwide in 2014 was 66, two-thirds of whom killed in war zones. The deadliest areas for the journalists that year were Syria and Palestine, Ukraine, Iraq and Libya. The number of journalists forced to flee their country has doubled since 2013, and the number of journalists convicted by their respective governments has risen to 178, most of them in Egypt, Ukraine, China, Eritrea and Iran. Another point mentioned in the annual report is the reduction of the number of journalists killed.

Report 2015

According to the Reporters without Borders (RSF) released its annual report on Thursday, February 12, 2015. It surveyed 180 countries, including Iran, and ranked them in terms of press freedom, independent media, and the status of correspondents and journalists. Iran ranks 173rd, indicating that the situation of Freedom of the press and journalists has not improved despite the promises of Rouhani's government, but the efforts of the organization's concerns about the situation of journalists in Iran continue. According to the report, also named Iran ranks third in the world where journalists are imprisoned. The organization announced the number of journalists killed for their careers, or suspiciously 110 dead, during 2015.

Report 2016

According to the Reporters without Borders (RSF) released, its annual report on December 13, 2016, states that in 2016, there were 348 imprisoned journalists and 52 hostages. After Turkey, China, Syria, Egypt and Iran are nearly two-thirds of imprisoned journalists in the world. "According to the report, the role of the journalist's citizen has been emphasized in recent years, especially in suppressive regimes or in war-torn countries. Which have played a decisive role in reflecting and publishing news."

Report 2017

According to the Reporters without Borders (RSF) released, its annual report on 2017, 65 journalists, including 50 professional journalists killed, 326 prisoners and 54 journalists have taken hostage. China, Turkey, Vietnam, Iran and Syria are the largest prisons for journalists and media activists. In 2017, over 65 journalists, Citizen Correspondents and media colleagues killed worldwide.

Report 2018

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) on the 2018 annual report of deadly violence and abuse of journalists, announced that over 80 journalists have been killed and 348 are currently being imprisoned, and another 60 are being held hostage, indicating Iran is the most repressive countries for journalists. The (RSF) also named Iran as one of the five countries where journalists are imprisoned, along with China, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Turkey. According to the report, Iran ranks 164th and remains one of the world's largest prisons for journalists.

Report 2019

According to the 2019 Reporters Without Borders' annual World Press Freedom Reporting Report, Norway was ranked among the 180 countries as the freest and safest countries for the media, with Iran ranked 170th, Saudi Arabia 172nd, Afghanistan 121st Turkmenistan 180th. Compared to last year, Iran's position is six points lower.

Report 2020

The 2020 World Press Freedom Index published on 21 April 2020 and intends to reflect the crisis has intensified the disinformation excesses of the Iranian government. Iran rises three places and exceeds to (173th). Hiding information, disinformation, official lies - methods used by the Islamic Republic in times of crisis and disaster- again, have been deployed on a regular basis since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead of informing the public about the reality of the pandemic, the Iranian government hiding information and disinformation (according to official figures, the country has had 70,000 cases and 4,500 deaths caused by the virus) could put the lives of millions of Iranians at risk.

Publications

In addition to its country, regional and thematic reports, RSF publishes a photography book 100 Photos for Press Freedom three times a year as a tool for advocacy and a fundraiser. It is a significant source of income for the organization, raising nearly a quarter of its funds in 2018:

Selected reports

- 2016 Freedom of expression under state of emergency, Turkey (with ARTICLE 19 and others)

- 2016 When oligarchs go shopping

- 2017 Who owns the media?

- 2017 Media Ownership Monitor, Ukraine (with Ukrainian Institute of Mass Information)

- 2018 Women's Rights: forbidden subject

- 2018 Journalists: the bête noire of organized crime

- 2018 Cambodia: independent press in ruins

- 2018 Women's rights: forbidden subject

- 2019 China's Pursuit of a New World Order Media

- 2019 Media Ownership Monitor, Pakistan (with Freedom Network)

Statements

On June 25, 2020, Reporters Without Borders issued a statement entitled "Enforced online repentance, Iran's new method of repression". According to the report, the Revolutionary Guards summoned a number of journalists, writers and human rights activists and threatened to detain them, forcing them to express their regrets or apologies for publishing their comments in cyberspace in order to silence them.

On Saturday, February 22, 2020, Reporters Without Borders issued a statement condemning the IRGC's call for journalists to be detained in Iran. IRGC intelligence has summoned some journalists and banned any media activities. Reporters Without Borders described the IRGC's intelligence action as "arbitrary and illegal" and aimed at "preventing journalists from being informed on social media."

Following the outbreak of the Coronavirus coronations in Iran, Reporters Without Borders on Thursday, March 6, issued a statement expressing concern over the safety of the imprisoned journalists, stressed that they were in danger of death.

On April 16, 2020, Reporters Without Borders has written a letter to two United Nations special rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and Health, urging the United Nations to issue serious warnings to governments that restrict freedom of expression in the context of the coronavirus epidemic. The letter, signed by Christian Mihr, Director, Reporters without Borders (RSF) Germany, states: "Freedom of the press and access to information are more important than ever at the time of Corona's pandemic."

On June 25, 2020, Reporters Without Borders issued a statement entitled "Online Repentance, a New Method of Repression in the Islamic Republic of Iran." According to the report, the Revolutionary Guards summoned and threatened to detain a number of journalists, writers, and human rights activists, forcing them to express regret or apology for posting their views online to silence them. The organization condemned the pressure, threats and silence of social activists.

On April 21, 2020, The RSF based in Paris said that the pandemic has amplified and highlighted many crises and over shadowed freedom of the press. Pointing the global impact of the coronavirus crisis, in a statement, the high representative of the EU, Josef Bourl reminded that the pandemic should not be used to justify the limitation of democratic and civil atmosphere and respecting the rule of law and international commitments. It should not limit the freedom of speech and media and also access to the information, both online and offline. These measures should not be used for restriction of human rights advocates, reporters, media staffs, and institutions of civil societies.

Funding

RSF's budget for 2018 totalled €6.1m. Fifty per cent of the organization's income comes from public subsidy; 12 per cent from foundations; 24 per cent from the publication of photography books and 9 per cent from public donations. Foundations supporting RSF's work include Adessium, IEDDH (International Cooperation and Development, European Commission), Sida (Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency), and Omidyar.

RSF has attracted criticism in previous years for accepting funding from the National Endowment for Democracy in the US and the Center for a Free Cuba. At the time, secretary-general Robert Ménard pointed out that funding from NED totalled 0.92 per cent of RSF's budget and supported African journalists and their families. RSF ceased its relationship with the Center for a Free Cuba in 2008.

Public profile

Recognition

RSF has received multiple international awards honouring its achievements:

- 1992: received the "Lorenzo Natali Prize" from the European Commission for defending human rights and democracy.

- 1997: received the "Journalism and Democracy Prize" from the Parliament Assembly of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE).

- 2005: shared the European Parliament's Sakharov Prize for "Freedom of Thought" with Nigerian human rights lawyer Hauwa Ibrahim and Cuba's Ladies in White movement.

- 2007: received the "Asia Democracy and Human Rights Award" from Taiwan Foundation for Democracy and the "Dawit Isaak Prize" from Swedish Publicists' Association.

- 2008: received the "Kahlil Gibran Award for Institutional Excellence" from the Arab American Institute Foundation.

- 2009: shared the "Roland Berger Human Dignity Award" with Iranian human rights lawyer and Nobel peace laureate Shirin Ebadi.

- 2009: received the "Médaille Charlemagne" for European Media.

- 2012: received the "Club Internacional de Prensa" Award, in Madrid.

- 2013: received the "Freedom of Speech Award" from the International Association of Press Clubs, in Warsaw.

- 2014: City of Bonn's 2014 DemokratiePreis.

- 2019: Dan David Prize, Defending Democracy, jointly with Michael Ignatieff

RSF was criticized for accepting the Dan David Prize, awarded by the Dan David Foundation in Israel.

Criticism

Funding

Reports published in the Council on Hemispheric Affairs and the US Newspaper Guild journal in 2005 criticized RSF for receiving funding from the US government and Cuba opposition groups, and for being part of a "neocons crusade" against the Castro regime. RSF denied the allegations of a political agenda, but confirmed that it had received a grant from the National Endowment for Democracy which is funded through the State Department and from the Centre for a Free Cuba. In 2006, online magazine CounterPunch claimed that RSF had falsely linked former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide to the murder of journalists and had failed to criticize his successor's crackdown on press freedom. RSF was criticized for supporting media outlets that were in favour of the coup attempt in Venezuela in 2002. In response, RSF pointed out that it had in fact condemned media support of the coup.

Otto Reich

Lucie Morillon, RWB's then-Washington representative, confirmed in an interview on 29 April 2005 that the organization had a contract with US State Department's Special Envoy to the Western Hemisphere, Otto Reich, who signed it in his capacity as a trustee for the Center for a Free Cuba, to inform Europeans about the repression of journalists in Cuba. CounterPunch, a critic of RWB, cited Reich's involvement with the group as a source of controversy: when Reich headed the Reagan administration's Office of Public Diplomacy in the 1980s, the body partook in what its officials termed "White Propaganda" – covert dissemination of information to influence domestic opinion regarding US backing for military campaigns against left-wing governments in Latin America.

Cuba

RWB has been highly critical of press freedom in Cuba, describing the Cuban government as "totalitarian", and engages in direct campaigning against it. RWB's campaign includes declarations on radio and television, full-page ads in Parisian dailies, posters, leafletting at airports, and an April 2003 occupation of the Cuban tourism office in Paris. A Paris court (tribunal de grande instance) ordered RWB to pay 6,000 Euros to the daughter and heir of Alberto Korda for non-compliance with a court order of 9 July 2003 banning it from using Korda's famous (and copyrighted) photograph of Ernesto "Che" Guevara in a beret, taken at the funeral of La Coubre victims. RWB said it was "relieved" it was not given a harsher sentence. The face had been superimposed by RWB with that of a May 1968 CRS anti-riot police agent, and the postcard handed out at Orly Airport in Paris to tourists boarding on flights for Cuba. On 24 April 2003, RWB organized a demonstration outside the Cuban embassy in Paris

RWB, as well as Ménard himself, in turn has been described as an "ultra-reactionary" organization by the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Cuban Communist Party, Granma. Tensions between Cuban authorities and RWB are high, particularly after the imprisonment in 2003 of 75 dissidents (27 journalists) by the Cuban Government, including Raúl Rivero and Óscar Elías Biscet. An article by John Cherian in the Indian magazine Frontline alleged that RWB "is reputed to have strong links with Western intelligence agencies" and "Cuba has accused Robert Meynard [sic] the head of the group, of having CIA links".

RWB has denied that its campaigning on Cuba are related to payments it has received from anti-Castro organisations. In 2004, it received $50,000 from the Miami-based exile group, the Center for a Free Cuba, which was personally signed by the US State Department's Special Envoy to the Western Hemisphere, Otto Reich. RWB has also received extensive funding from other institutions long critical of Fidel Castro's government, including the International Republican Institute.

Haiti

In 2004, Reporters Without Borders released an annual report on Haiti, saying that a "climate of terror" existed in which attacks and threats persisted against journalists who were critical of Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

An August 2006 article in CounterPunch accused RWB of ignoring similar attacks on journalists under the Latortue government in 2005 and 2006, including that of Pacifica Radio reporter Kevin Pina. Pina himself said:

It was clear early on that RWB and Robert Menard were not acting as objective guardians of freedom of the press in Haiti but rather as central actors in what can only be described as a disinformation campaign against Aristide's government ... They provide false information and skewed reports to build internal opposition to governments seen as uncontrollable and unpalatable to Washington while softening the ground for their eventual removal by providing justification under the pretext of attacks on the freedom of the press.

Venezuela

Le Monde diplomatique has criticized RWB's attitude towards Hugo Chávez's government in Venezuela, in particular during the 2002 coup attempt. RWB is said to have lent its support for Venezuelan pro-coup media outlets, and have had as a Caracas correspondent María Sol Pérez-Schael, an opposition adviser. In a right of reply, Robert Ménard declared that RWB had also condemned the Venezuela media's support of the coup attempt. RWB has also been criticized for supporting Globovision's version of events about its false reporting in relation to a 2009 earthquake, claiming Globovision was "being hounded by the government and the administration". RSF has received criticism in relation to historic campaigns.

Overemphasis on "third-world dictatorships"; alleged bias in favor of Europe and the U.S.

In 2007 John Rosenthal argued that RWB showed a bias in favor of European countries. In the 2009 article about RWB and Venezuela cited above, Salim Lamrani stated that "RSF is not an organization that defends freedom of the press, but is an obscure entity with a political agenda precisely commissioned to discredit through all possible means the progressive governments in the world that find themselves on the United States' blacklist."

Reports published in the Council on Hemispheric Affairs and the US Newspaper Guild journal in 2005 criticised RSF for receiving funding from the US government and Cuba opposition groups, and for being part of a ‘neocons crusade’ against the Castro regime. RSF denied the allegations of a political agenda, but confirmed that it had received a grant from the National Endowment for Democracy which is funded through the State Department and from the Centre for a Free Cuba.

The Observatoire de l'Action Humanitaire (Centre for Humanitarian Action) criticized RWB's lukewarm criticism of US forces for their shelling, in 2003, of Palestine Hotel, in Baghdad, Iraq, which killed two Reuters journalists. The family of one of the deceased journalists, Spanish citizen José Couso, refused to allow the Spain chapter of RWB to attach its name to a legal action led by the family against the US Army, voicing disgust at the fact that RWB interviewed US forces responsible for the shelling, but not the surviving journalists, and that RWB showed acquiescence to the US Army by thanking them for their "precious help".

In 2006, online magazine CounterPunch claimed that RSF had falsely linked former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide to the murder of journalists and had failed to criticise his successor's crackdown on press freedom.

According to the Observatoire, ever since Robert Ménard was replaced by Jean-François Julliard in September 2008, RWB has been concerned with violations of press freedom not only in "third-world dictatorships" but also in developed countries like France. Through widening its geographical scope, RWB aims at countering accusations of overly focusing on left-wing regimes unfriendly to the US. For example, RWB condemned the 35-year sentence received by American soldier Chelsea Manning, calling it "disproportionate" and arguing that it reveals how "vulnerable" whistleblowers are. In April 2019, the RWB stated the arrest of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange could "set a dangerous precedent for journalists, whistleblowers, and other journalistic sources that the US may wish to pursue in the future."

RSF was criticised for supporting media outlets that were in favour of the coup attempt in Venezuela in 2002. In response, RSF pointed out that it had in fact condemned media support of the coup.