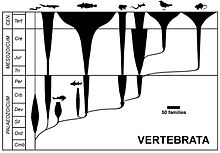

The evolution of birds began in the Jurassic Period, with the earliest birds derived from a clade of theropod dinosaurs named Paraves. Birds are categorized as a biological class, Aves. For more than a century, the small theropod dinosaur Archaeopteryx lithographica from the Late Jurassic period was considered to have been the earliest bird. Modern phylogenies place birds in the dinosaur clade Theropoda. According to the current consensus, Aves and a sister group, the order Crocodilia, together are the sole living members of an unranked "reptile" clade, the Archosauria. Four distinct lineages of bird survived the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago, giving rise to ostriches and relatives (Paleognathae), ducks and relatives (Anseriformes), ground-living fowl (Galliformes), and "modern birds" (Neoaves).

Phylogenetically, Aves is usually defined as all descendants of the most recent common ancestor of a specific modern bird species (such as the house sparrow, Passer domesticus), and either Archaeopteryx, or some prehistoric species closer to Neornithes (to avoid the problems caused by the unclear relationships of Archaeopteryx to other theropods). If the latter classification is used then the larger group is termed Avialae. Currently, the relationship between dinosaurs, Archaeopteryx, and modern birds is still under debate.

Origins

There is significant evidence that birds emerged within theropod dinosaurs, specifically, that birds are members of Maniraptora, a group of theropods which includes dromaeosaurs and oviraptorids, among others. As more non-avian theropods that are closely related to birds are discovered, the formerly clear distinction between non-birds and birds becomes less so. This was noted already in the 19th century, with Thomas Huxley writing:

We have had to stretch the definition of the class of birds so as to include birds with teeth and birds with paw-like fore limbs and long tails. There is no evidence that Compsognathus possessed feathers; but, if it did, it would be hard indeed to say whether it should be called a reptilian bird or an avian reptile.

Discoveries in northeast China (Liaoning Province) demonstrate that many small theropod dinosaurs did indeed have feathers, among them the compsognathid Sinosauropteryx and the microraptorian dromaeosaurid Sinornithosaurus. This has contributed to this ambiguity of where to draw the line between birds and reptiles. Cryptovolans, a dromaeosaurid found in 2002 (which may be a junior synonym of Microraptor) was capable of powered flight, possessed a sternal keel and had ribs with uncinate processes. Cryptovolans seems to make a better "bird" than Archaeopteryx which lacks some of these modern bird features. Because of this, some paleontologists have suggested that dromaeosaurs are actually basal birds whose larger members are secondarily flightless, i.e. that dromaeosaurs evolved from birds and not the other way around. Evidence for this theory is currently inconclusive, but digs continue to unearth fossils (especially in China) of feathered dromaeosaurs. At any rate, it is fairly certain that flight utilizing feathered wings existed in the mid-Jurassic theropods. The Cretaceous unenlagiine Rahonavis also possesses features suggesting it was at least partially capable of powered flight.

Although ornithischian (bird-hipped) dinosaurs share the same hip structure as birds, birds actually originated from the saurischian (lizard-hipped) dinosaurs if the dinosaurian origin theory is correct. They thus arrived at their hip structure condition independently. In fact, a bird-like hip structure also developed a third time among a peculiar group of theropods, the Therizinosauridae.

An alternate theory to the dinosaurian origin of birds, espoused by a few scientists, notably Larry Martin and Alan Feduccia, states that birds (including maniraptoran "dinosaurs") evolved from early archosaurs like Longisquama. This theory is contested by most other paleontologists and experts in feather development and evolution.

Mesozoic birds

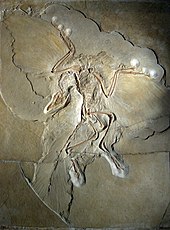

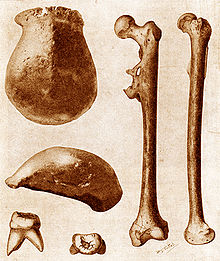

The basal bird Archaeopteryx, from the Jurassic, is well known as one of the first "missing links" to be found in support of evolution in the late 19th century. Though it is not considered a direct ancestor of modern birds, it gives a fair representation of how flight evolved and how the very first bird might have looked. It may be predated by Protoavis texensis, though the fragmentary nature of this fossil leaves it open to considerable doubt whether this was a bird ancestor. The skeleton of all early bird candidates is basically that of a small theropod dinosaur with long, clawed hands, though the exquisite preservation of the Solnhofen Plattenkalk shows Archaeopteryx was covered in feathers and had wings. While Archaeopteryx and its relatives may not have been very good fliers, they would at least have been competent gliders, setting the stage for the evolution of life on the wing.

The evolutionary trend among birds has been the reduction of anatomical elements to save weight. The first element to disappear was the bony tail, being reduced to a pygostyle and the tail function taken over by feathers. Confuciusornis is an example of their trend. While keeping the clawed fingers, perhaps for climbing, it had a pygostyle tail, though longer than in modern birds. A large group of birds, the Enantiornithes, evolved into ecological niches similar to those of modern birds and flourished throughout the Mesozoic. Though their wings resembled those of many modern bird groups, they retained the clawed wings and a snout with teeth rather than a beak in most forms. The loss of a long tail was followed by a rapid evolution of their legs which evolved to become highly versatile and adaptable tools that opened up new ecological niches.

The Cretaceous saw the rise of more modern birds with a more rigid ribcage with a carina and shoulders able to allow for a powerful upstroke, essential to sustained powered flight. Another improvement was the appearance of an alula, used to achieve better control of landing or flight at low speeds. They also had a more derived pygostyle, with a ploughshare-shaped end. An early example is Yanornis. Many were coastal birds, strikingly resembling modern shorebirds, like Ichthyornis, or ducks, like Gansus. Some evolved as swimming hunters, like the Hesperornithiformes – a group of flightless divers resembling grebes and loons. While modern in most respects, most of these birds retained typical reptilian-like teeth and sharp claws on the manus.

The modern toothless birds evolved from the toothed ancestors in the Cretaceous. Meanwhile, the earlier primitive birds, particularly the Enantiornithes, continued to thrive and diversify alongside the pterosaurs through this geologic period until they became extinct due to the K–T extinction event. All but a few groups of the toothless Neornithes were also cut short. The surviving lineages of birds were the comparatively primitive Paleognathae (ostrich and its allies), the aquatic duck lineage, the terrestrial fowl, and the highly volant Neoaves.

Adaptive radiation of modern birds

Modern birds are classified in Neornithes, which are now known to have evolved into some basic lineages by the end of the Cretaceous. The Neornithes are split into the paleognaths and neognaths.

The paleognaths include the tinamous (found only in Central and South America) and the ratites, which nowadays are found almost exclusively on the Southern Hemisphere. The ratites are large flightless birds, and include ostriches, rheas, cassowaries, kiwis and emus. A few scientists propose that the ratites represent an artificial grouping of birds which have independently lost the ability to fly in a number of unrelated lineages. In any case, the available data regarding their evolution is still very confusing, partly because there are no uncontroversial fossils from the Mesozoic. Phylogenetic analysis supports the assertion that the ratites are polyphyletic and do not represent a valid grouping of birds.

The basal divergence from the remaining Neognathes was that of the Galloanserae, the superorder containing the Anseriformes (ducks, geese and swans), and the Galliformes (chickens, turkeys, pheasants, and their allies). The presence of basal anseriform fossils in the Mesozoic and likely some galliform fossils implies the presence of paleognaths at the same time, in spite of the absence of fossil evidence.

The dates for the splits are a matter of considerable debate amongst scientists. It is agreed that the Neornithes evolved in the Cretaceous and that the split between the Galloanserae and the other neognaths – the Neoaves – occurred before the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, but there are different opinions about whether the radiation of the remaining neognaths occurred before or after the extinction of the other dinosaurs. This disagreement is in part caused by a divergence in the evidence, with molecular dating suggesting a Cretaceous radiation, a small and equivocal neoavian fossil record from Cretaceous, and most living families turning up during the Paleogene. Attempts made to reconcile the molecular and fossil evidence have proved controversial.

On the other hand, two factors must be considered: First, molecular clocks cannot be considered reliable in the absence of robust fossil calibration, whereas the fossil record is naturally incomplete. Second, in reconstructed phylogenetic trees, the time and pattern of lineage separation corresponds to the evolution of the characters (such as DNA sequences, morphological traits etc.) studied, not to the actual evolutionary pattern of the lineages; these ideally should not differ by much, but may well do so in practice.

Considering this, it is easy to see that fossil data, compared to molecular data, tends to be more accurate in general, but also to underestimate divergence times: morphological traits, being the product of entire developmental genetics networks, usually only start to diverge some time after a lineage split would become apparent in DNA sequence comparison – especially if the sequences used contain many silent mutations.

The authors of a May 2018 report in Current Biology think that the birds that survived the end-of-Cetaceous disaster were Neornithes, Neognathae (Galloanserae + Neoaves), not tree-living, and could not fly far, because of the worldwide destruction of forests and that it took a long time for the world's forests to return properly. Virtually the same conclusions were already reached before, in a 2016 book on avian evolution.

In August 2020 scientists reported that bird skull evolution decelerated compared with the evolution of their dinosaur predecessors after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, rather than accelerating as often believed to have caused the cranial shape diversity of modern birds.

Classification of modern species

The phylogenetic classification of birds is a contentious issue. Sibley & Ahlquist's Phylogeny and Classification of Birds (1990) is a landmark work on the classification of birds (although frequently debated and constantly revised). A preponderance of evidence suggests that most modern bird orders constitute good clades. However, scientists are not in agreement as to the precise relationships between the main clades. Evidence from modern bird anatomy, fossils and DNA have all been brought to bear on the problem but no strong consensus has emerged.

Current evolutionary trends in birds

Evolution generally occurs at a scale far too slow to be witnessed by humans. However, bird species are currently going extinct at a far greater rate than any possible speciation or other generation of new species. The disappearance of a population, subspecies, or species represents the permanent loss of a range of genes.

Another concern with evolutionary implications is a suspected increase in hybridization. This may arise from human alteration of habitats enabling related allopatric species to overlap. Forest fragmentation can create extensive open areas, connecting previously isolated patches of open habitat. Populations that were isolated for sufficient time to diverge significantly, but not sufficient to be incapable of producing fertile offspring may now be interbreeding so broadly that the integrity of the original species may be compromised. For example, the many hybrid hummingbirds found in northwest South America may represent a threat to the conservation of the distinct species involved.

Several species of birds have been bred in captivity to create variations on wild species. In some birds this is limited to color variations, while others are bred for larger egg or meat production, for flightlessness or other characteristics.

In December 2019 the results of a joint study by Chicago's Field Museum and the University of Michigan into changes in the morphology of birds was published in Ecology Letters. The study uses bodies of birds which died as a result of colliding with buildings in Chicago, Illinois, since 1978. The sample is made up of over 70,000 specimens from 52 species and span the period from 1978 to 2016. The study shows that the length of birds' lower leg bones (an indicator of body sizes) shortened by an average of 2.4% and their wings lengthened by 1.3%. The findings of the study suggest the morphological changes are the result of climate change, demonstrating an example of evolutionary change following Bergmann's rule.