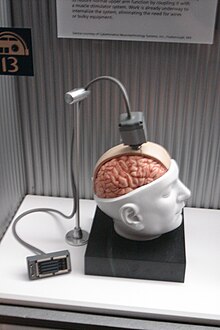

A brain–computer interface (BCI), sometimes called a neural control interface (NCI), mind–machine interface (MMI), direct neural interface (DNI), or brain–machine interface (BMI), is a direct communication pathway between an enhanced or wired brain and an external device. BCIs are often directed at researching, mapping, assisting, augmenting, or repairing human cognitive or sensory-motor functions.

Research on BCIs began in the 1970s at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) under a grant from the National Science Foundation, followed by a contract from DARPA. The papers published after this research also mark the first appearance of the expression brain–computer interface in scientific literature.

Due to the cortical plasticity of the brain, signals from implanted prostheses can, after adaptation, be handled by the brain like natural sensor or effector channels. Following years of animal experimentation, the first neuroprosthetic devices implanted in humans appeared in the mid-1990s.

Recently, studies in human-computer interaction through the application of machine learning with statistical temporal features extracted from the frontal lobe, EEG brainwave data has shown high levels of success in classifying mental states (Relaxed, Neutral, Concentrating), mental emotional states (Negative, Neutral, Positive) and thalamocortical dysrhythmia.

History

The history of brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) starts with Hans Berger's discovery of the electrical activity of the human brain and the development of electroencephalography (EEG). In 1924 Berger was the first to record human brain activity by means of EEG. Berger was able to identify oscillatory activity, such as Berger's wave or the alpha wave (8–13 Hz), by analyzing EEG traces.

Berger's first recording device was very rudimentary. He inserted silver wires under the scalps of his patients. These were later replaced by silver foils attached to the patient's head by rubber bandages. Berger connected these sensors to a Lippmann capillary electrometer, with disappointing results. However, more sophisticated measuring devices, such as the Siemens double-coil recording galvanometer, which displayed electric voltages as small as one ten thousandth of a volt, led to success.

Berger analyzed the interrelation of alternations in his EEG wave diagrams with brain diseases. EEGs permitted completely new possibilities for the research of human brain activities.

Although the term had not yet been coined, one of the earliest examples of a working brain-machine interface was the piece Music for Solo Performer (1965) by the American composer Alvin Lucier. The piece makes use of EEG and analog signal processing hardware (filters, amplifiers, and a mixing board) to stimulate acoustic percussion instruments. To perform the piece one must produce alpha waves and thereby "play" the various percussion instruments via loudspeakers which are placed near or directly on the instruments themselves.

UCLA Professor Jacques Vidal coined the term "BCI" and produced the first peer-reviewed publications on this topic. Vidal is widely recognized as the inventor of BCIs in the BCI community, as reflected in numerous peer-reviewed articles reviewing and discussing the field (e.g.). His 1973 paper stated the "BCI challenge": Control of external objects using EEG signals. Especially he pointed out to Contingent Negative Variation (CNV) potential as a challenge for BCI control. The 1977 experiment Vidal described was the first application of BCI after his 1973 BCI challenge. It was a noninvasive EEG (actually Visual Evoked Potentials (VEP)) control of a cursor-like graphical object on a computer screen. The demonstration was movement in a maze.

After his early contributions, Vidal was not active in BCI research, nor BCI events such as conferences, for many years. In 2011, however, he gave a lecture in Graz, Austria, supported by the Future BNCI project, presenting the first BCI, which earned a standing ovation. Vidal was joined by his wife, Laryce Vidal, who previously worked with him at UCLA on his first BCI project.

In 1988, a report was given on noninvasive EEG control of a physical object, a robot. The experiment described was EEG control of multiple start-stop-restart of the robot movement, along an arbitrary trajectory defined by a line drawn on a floor. The line-following behavior was the default robot behavior, utilizing autonomous intelligence and autonomous source of energy. This 1988 report written by Stevo Bozinovski, Mihail Sestakov, and Liljana Bozinovska was the first one about a robot control using EEG.

In 1990, a report was given on a closed loop, bidirectional adaptive BCI controlling computer buzzer by an anticipatory brain potential, the Contingent Negative Variation (CNV) potential. The experiment described how an expectation state of the brain, manifested by CNV, controls in a feedback loop the S2 buzzer in the S1-S2-CNV paradigm. The obtained cognitive wave representing the expectation learning in the brain is named Electroexpectogram (EXG). The CNV brain potential was part of the BCI challenge presented by Vidal in his 1973 paper.

BCIs versus neuroprosthetics

Neuroprosthetics is an area of neuroscience concerned with neural prostheses, that is, using artificial devices to replace the function of impaired nervous systems and brain-related problems, or of sensory organs or organs itself (bladder, diaphragm, etc.). As of December 2010, cochlear implants had been implanted as neuroprosthetic device in approximately 220,000 people worldwide. There are also several neuroprosthetic devices that aim to restore vision, including retinal implants. The first neuroprosthetic device, however, was the pacemaker.

The terms are sometimes used interchangeably. Neuroprosthetics and BCIs seek to achieve the same aims, such as restoring sight, hearing, movement, ability to communicate, and even cognitive function. Both use similar experimental methods and surgical techniques.

Animal BCI research

Several laboratories have managed to record signals from monkey and rat cerebral cortices to operate BCIs to produce movement. Monkeys have navigated computer cursors on screen and commanded robotic arms to perform simple tasks simply by thinking about the task and seeing the visual feedback, but without any motor output. In May 2008 photographs that showed a monkey at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center operating a robotic arm by thinking were published in a number of well-known science journals and magazines.

Early work

In 1969 the operant conditioning studies of Fetz and colleagues, at the Regional Primate Research Center and Department of Physiology and Biophysics, University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle, showed for the first time that monkeys could learn to control the deflection of a biofeedback meter arm with neural activity. Similar work in the 1970s established that monkeys could quickly learn to voluntarily control the firing rates of individual and multiple neurons in the primary motor cortex if they were rewarded for generating appropriate patterns of neural activity.

Studies that developed algorithms to reconstruct movements from motor cortex neurons, which control movement, date back to the 1970s. In the 1980s, Apostolos Georgopoulos at Johns Hopkins University found a mathematical relationship between the electrical responses of single motor cortex neurons in rhesus macaque monkeys and the direction in which they moved their arms (based on a cosine function). He also found that dispersed groups of neurons, in different areas of the monkey's brains, collectively controlled motor commands, but was able to record the firings of neurons in only one area at a time, because of the technical limitations imposed by his equipment.

There has been rapid development in BCIs since the mid-1990s. Several groups have been able to capture complex brain motor cortex signals by recording from neural ensembles (groups of neurons) and using these to control external devices.

Prominent research successes

Kennedy and Yang Dan

Phillip Kennedy (who later founded Neural Signals in 1987) and colleagues built the first intracortical brain–computer interface by implanting neurotrophic-cone electrodes into monkeys.

In 1999, researchers led by Yang Dan at the University of California, Berkeley decoded neuronal firings to reproduce images seen by cats. The team used an array of electrodes embedded in the thalamus (which integrates all of the brain's sensory input) of sharp-eyed cats. Researchers targeted 177 brain cells in the thalamus lateral geniculate nucleus area, which decodes signals from the retina. The cats were shown eight short movies, and their neuron firings were recorded. Using mathematical filters, the researchers decoded the signals to generate movies of what the cats saw and were able to reconstruct recognizable scenes and moving objects. Similar results in humans have since been achieved by researchers in Japan.

Nicolelis

Miguel Nicolelis, a professor at Duke University, in Durham, North Carolina, has been a prominent proponent of using multiple electrodes spread over a greater area of the brain to obtain neuronal signals to drive a BCI.

After conducting initial studies in rats during the 1990s, Nicolelis and his colleagues developed BCIs that decoded brain activity in owl monkeys and used the devices to reproduce monkey movements in robotic arms. Monkeys have advanced reaching and grasping abilities and good hand manipulation skills, making them ideal test subjects for this kind of work.

By 2000, the group succeeded in building a BCI that reproduced owl monkey movements while the monkey operated a joystick or reached for food. The BCI operated in real time and could also control a separate robot remotely over Internet protocol. But the monkeys could not see the arm moving and did not receive any feedback, a so-called open-loop BCI.

Later experiments by Nicolelis using rhesus monkeys succeeded in closing the feedback loop and reproduced monkey reaching and grasping movements in a robot arm. With their deeply cleft and furrowed brains, rhesus monkeys are considered to be better models for human neurophysiology than owl monkeys. The monkeys were trained to reach and grasp objects on a computer screen by manipulating a joystick while corresponding movements by a robot arm were hidden. The monkeys were later shown the robot directly and learned to control it by viewing its movements. The BCI used velocity predictions to control reaching movements and simultaneously predicted handgripping force. In 2011 O'Doherty and colleagues showed a BCI with sensory feedback with rhesus monkeys. The monkey was brain controlling the position of an avatar arm while receiving sensory feedback through direct intracortical stimulation (ICMS) in the arm representation area of the sensory cortex.

Donoghue, Schwartz and Andersen

Other laboratories which have developed BCIs and algorithms that decode neuron signals include those run by John Donoghue at Brown University, Andrew Schwartz at the University of Pittsburgh and Richard Andersen at Caltech. These researchers have been able to produce working BCIs, even using recorded signals from far fewer neurons than did Nicolelis (15–30 neurons versus 50–200 neurons).

Donoghue's group reported training rhesus monkeys to use a BCI to track visual targets on a computer screen (closed-loop BCI) with or without assistance of a joystick. Schwartz's group created a BCI for three-dimensional tracking in virtual reality and also reproduced BCI control in a robotic arm. The same group also created headlines when they demonstrated that a monkey could feed itself pieces of fruit and marshmallows using a robotic arm controlled by the animal's own brain signals.

Andersen's group used recordings of premovement activity from the posterior parietal cortex in their BCI, including signals created when experimental animals anticipated receiving a reward.

Other research

In addition to predicting kinematic and kinetic parameters of limb movements, BCIs that predict electromyographic or electrical activity of the muscles of primates are being developed. Such BCIs could be used to restore mobility in paralyzed limbs by electrically stimulating muscles.

Miguel Nicolelis and colleagues demonstrated that the activity of large neural ensembles can predict arm position. This work made possible creation of BCIs that read arm movement intentions and translate them into movements of artificial actuators. Carmena and colleagues programmed the neural coding in a BCI that allowed a monkey to control reaching and grasping movements by a robotic arm. Lebedev and colleagues argued that brain networks reorganize to create a new representation of the robotic appendage in addition to the representation of the animal's own limbs.

In 2019, researchers from UCSF published a study where they demonstrated a BCI that had the potential to help patients with speech impairment caused by neurological disorders. Their BCI used high-density electrocorticography to tap neural activity from a patient's brain and used deep learning methods to synthesize speech.

The biggest impediment to BCI technology at present is the lack of a sensor modality that provides safe, accurate and robust access to brain signals. It is conceivable or even likely, however, that such a sensor will be developed within the next twenty years. The use of such a sensor should greatly expand the range of communication functions that can be provided using a BCI.

Development and implementation of a BCI system is complex and time-consuming. In response to this problem, Gerwin Schalk has been developing a general-purpose system for BCI research, called BCI2000. BCI2000 has been in development since 2000 in a project led by the Brain–Computer Interface R&D Program at the Wadsworth Center of the New York State Department of Health in Albany, New York, United States.

A new 'wireless' approach uses light-gated ion channels such as Channelrhodopsin to control the activity of genetically defined subsets of neurons in vivo. In the context of a simple learning task, illumination of transfected cells in the somatosensory cortex influenced the decision making process of freely moving mice.

The use of BMIs has also led to a deeper understanding of neural networks and the central nervous system. Research has shown that despite the inclination of neuroscientists to believe that neurons have the most effect when working together, single neurons can be conditioned through the use of BMIs to fire at a pattern that allows primates to control motor outputs. The use of BMIs has led to development of the single neuron insufficiency principle which states that even with a well tuned firing rate single neurons can only carry a narrow amount of information and therefore the highest level of accuracy is achieved by recording firings of the collective ensemble. Other principles discovered with the use of BMIs include the neuronal multitasking principle, the neuronal mass principle, the neural degeneracy principle, and the plasticity principle.

BCIs are also proposed to be applied by users without disabilities. A user-centered categorization of BCI approaches by Thorsten O. Zander and Christian Kothe introduces the term passive BCI. Next to active and reactive BCI that are used for directed control, passive BCIs allow for assessing and interpreting changes in the user state during Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). In a secondary, implicit control loop the computer system adapts to its user improving its usability in general.

Beyond BCI systems that decode neural activity to drive external effectors, BCI systems may be used to encode signals from the periphery. These sensory BCI devices enable real-time, behaviorally-relevant decisions based upon closed-loop neural stimulation.

The BCI Award

The Annual BCI Research Award is awarded in recognition of outstanding and innovative research in the field of Brain-Computer Interfaces. Each year, a renowned research laboratory is asked to judge the submitted projects. The jury consists of world-leading BCI experts recruited by the awarding laboratory. The jury selects twelve nominees, then chooses a first, second, and third-place winner, who receive awards of $3,000, $2,000, and $1,000, respectively.

Human BCI research

Invasive BCIs

Invasive BCI requires surgery to implant electrodes under scalp for communicating brain signals. The main advantage is to provide more accurate reading; however, its downside includes side effects from the surgery. After the surgery, scar tissues may form which can make brain signals weaker. In addition, according to the research of Abdulkader et al., (2015), the body may not accept the implanted electrodes and this can cause a medical condition.

Vision

Invasive BCI research has targeted repairing damaged sight and providing new functionality for people with paralysis. Invasive BCIs are implanted directly into the grey matter of the brain during neurosurgery. Because they lie in the grey matter, invasive devices produce the highest quality signals of BCI devices but are prone to scar-tissue build-up, causing the signal to become weaker, or even non-existent, as the body reacts to a foreign object in the brain.

In vision science, direct brain implants have been used to treat non-congenital (acquired) blindness. One of the first scientists to produce a working brain interface to restore sight was private researcher William Dobelle.

Dobelle's first prototype was implanted into "Jerry", a man blinded in adulthood, in 1978. A single-array BCI containing 68 electrodes was implanted onto Jerry's visual cortex and succeeded in producing phosphenes, the sensation of seeing light. The system included cameras mounted on glasses to send signals to the implant. Initially, the implant allowed Jerry to see shades of grey in a limited field of vision at a low frame-rate. This also required him to be hooked up to a mainframe computer, but shrinking electronics and faster computers made his artificial eye more portable and now enable him to perform simple tasks unassisted.

In 2002, Jens Naumann, also blinded in adulthood, became the first in a series of 16 paying patients to receive Dobelle's second generation implant, marking one of the earliest commercial uses of BCIs. The second generation device used a more sophisticated implant enabling better mapping of phosphenes into coherent vision. Phosphenes are spread out across the visual field in what researchers call "the starry-night effect". Immediately after his implant, Jens was able to use his imperfectly restored vision to drive an automobile slowly around the parking area of the research institute. Unfortunately, Dobelle died in 2004 before his processes and developments were documented. Subsequently, when Mr. Naumann and the other patients in the program began having problems with their vision, there was no relief and they eventually lost their "sight" again. Naumann wrote about his experience with Dobelle's work in Search for Paradise: A Patient's Account of the Artificial Vision Experiment and has returned to his farm in Southeast Ontario, Canada, to resume his normal activities.

Movement

BCIs focusing on motor neuroprosthetics aim to either restore movement in individuals with paralysis or provide devices to assist them, such as interfaces with computers or robot arms.

Researchers at Emory University in Atlanta, led by Philip Kennedy and Roy Bakay, were first to install a brain implant in a human that produced signals of high enough quality to simulate movement. Their patient, Johnny Ray (1944–2002), suffered from 'locked-in syndrome' after suffering a brain-stem stroke in 1997. Ray's implant was installed in 1998 and he lived long enough to start working with the implant, eventually learning to control a computer cursor; he died in 2002 of a brain aneurysm.

Tetraplegic Matt Nagle became the first person to control an artificial hand using a BCI in 2005 as part of the first nine-month human trial of Cyberkinetics's BrainGate chip-implant. Implanted in Nagle's right precentral gyrus (area of the motor cortex for arm movement), the 96-electrode BrainGate implant allowed Nagle to control a robotic arm by thinking about moving his hand as well as a computer cursor, lights and TV. One year later, professor Jonathan Wolpaw received the prize of the Altran Foundation for Innovation to develop a Brain Computer Interface with electrodes located on the surface of the skull, instead of directly in the brain.

More recently, research teams led by the Braingate group at Brown University and a group led by University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, both in collaborations with the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, have demonstrated further success in direct control of robotic prosthetic limbs with many degrees of freedom using direct connections to arrays of neurons in the motor cortex of patients with tetraplegia.

Partially invasive BCIs

Partially invasive BCI devices are implanted inside the skull but rest outside the brain rather than within the grey matter. They produce better resolution signals than non-invasive BCIs where the bone tissue of the cranium deflects and deforms signals and have a lower risk of forming scar-tissue in the brain than fully invasive BCIs. There has been preclinical demonstration of intracortical BCIs from the stroke perilesional cortex.

Electrocorticography (ECoG) measures the electrical activity of the brain taken from beneath the skull in a similar way to non-invasive electroencephalography, but the electrodes are embedded in a thin plastic pad that is placed above the cortex, beneath the dura mater. ECoG technologies were first trialled in humans in 2004 by Eric Leuthardt and Daniel Moran from Washington University in St Louis. In a later trial, the researchers enabled a teenage boy to play Space Invaders using his ECoG implant. This research indicates that control is rapid, requires minimal training, and may be an ideal tradeoff with regards to signal fidelity and level of invasiveness.

Signals can be either subdural or epidural, but are not taken from within the brain parenchyma itself. It has not been studied extensively until recently due to the limited access of subjects. Currently, the only manner to acquire the signal for study is through the use of patients requiring invasive monitoring for localization and resection of an epileptogenic focus.

ECoG is a very promising intermediate BCI modality because it has higher spatial resolution, better signal-to-noise ratio, wider frequency range, and less training requirements than scalp-recorded EEG, and at the same time has lower technical difficulty, lower clinical risk, and probably superior long-term stability than intracortical single-neuron recording. This feature profile and recent evidence of the high level of control with minimal training requirements shows potential for real world application for people with motor disabilities. Light reactive imaging BCI devices are still in the realm of theory.

Non-invasive BCIs

There have also been experiments in humans using non-invasive neuroimaging technologies as interfaces. The substantial majority of published BCI work involves noninvasive EEG-based BCIs. Noninvasive EEG-based technologies and interfaces have been used for a much broader variety of applications. Although EEG-based interfaces are easy to wear and do not require surgery, they have relatively poor spatial resolution and cannot effectively use higher-frequency signals because the skull dampens signals, dispersing and blurring the electromagnetic waves created by the neurons. EEG-based interfaces also require some time and effort prior to each usage session, whereas non-EEG-based ones, as well as invasive ones require no prior-usage training. Overall, the best BCI for each user depends on numerous factors.

Non-EEG-based human–computer interface

Electrooculography (EOG)

In 1989 report was given on control of a mobile robot by eye movement using Electrooculography (EOG) signals. A mobile robot was driven from a start to a goal point using five EOG commands, interpreted as forward, backward, left, right, and stop. The EOG as a challenge of controlling external objects was presented by Vidal in his 1973 paper.

Pupil-size oscillation

A 2016 article described an entirely new communication device and non-EEG-based human-computer interface, which requires no visual fixation, or ability to move the eyes at all. The interface is based on covert interest; directing one's attention to a chosen letter on a virtual keyboard, without the need to move one's eyes to look directly at the letter. Each letter has its own (background) circle which micro-oscillates in brightness differently from all of the other letters. The letter selection is based on best fit between unintentional pupil-size oscillation and the background circle's brightness oscillation pattern. Accuracy is additionally improved by the user's mental rehearsing of the words 'bright' and 'dark' in synchrony with the brightness transitions of the letter's circle.

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy

In 2014 and 2017, a BCI using functional near-infrared spectroscopy for "locked-in" patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) was able to restore some basic ability of the patients to communicate with other people.

Electroencephalography (EEG)-based brain-computer interfaces

After the BCI challenge was stated by Vidal in 1973, the initial reports on non-invasive approach included control of a cursor in 2D using VEP (Vidal 1977), control of a buzzer using CNV (Bozinovska et al. 1988, 1990), control of a physical object, a robot, using a brain rhythm (alpha) (Bozinovski et al. 1988), control of a text written on a screen using P300 (Farwell and Donchin, 1988).

In the early days of BCI research, another substantial barrier to using Electroencephalography (EEG) as a brain–computer interface was the extensive training required before users can work the technology. For example, in experiments beginning in the mid-1990s, Niels Birbaumer at the University of Tübingen in Germany trained severely paralysed people to self-regulate the slow cortical potentials in their EEG to such an extent that these signals could be used as a binary signal to control a computer cursor. (Birbaumer had earlier trained epileptics to prevent impending fits by controlling this low voltage wave.) The experiment saw ten patients trained to move a computer cursor by controlling their brainwaves. The process was slow, requiring more than an hour for patients to write 100 characters with the cursor, while training often took many months. However, the slow cortical potential approach to BCIs has not been used in several years, since other approaches require little or no training, are faster and more accurate, and work for a greater proportion of users.

Another research parameter is the type of oscillatory activity that is measured. Gert Pfurtscheller founded the BCI Lab 1991 and fed his research results on motor imagery in the first online BCI based on oscillatory features and classifiers. Together with Birbaumer and Jonathan Wolpaw at New York State University they focused on developing technology that would allow users to choose the brain signals they found easiest to operate a BCI, including mu and beta rhythms.

A further parameter is the method of feedback used and this is shown in studies of P300 signals. Patterns of P300 waves are generated involuntarily (stimulus-feedback) when people see something they recognize and may allow BCIs to decode categories of thoughts without training patients first. By contrast, the biofeedback methods described above require learning to control brainwaves so the resulting brain activity can be detected.

In 2005 it was reported research on EEG emulation of digital control circuits for BCI, with example of a CNV flip-flop. In 2009 it was reported noninvasive EEG control of a robotic arm using a CNV flip-flop. In 2011 it was reported control of two robotic arms solving Tower of Hanoi task with three disks using a CNV flip-flop. In 2015 it was described EEG-emulation of a Schmidt trigger, flip-flop, demultiplexer, and modem.

While an EEG based brain-computer interface has been pursued extensively by a number of research labs, recent advancements made by Bin He and his team at the University of Minnesota suggest the potential of an EEG based brain-computer interface to accomplish tasks close to invasive brain-computer interface. Using advanced functional neuroimaging including BOLD functional MRI and EEG source imaging, Bin He and co-workers identified the co-variation and co-localization of electrophysiological and hemodynamic signals induced by motor imagination. Refined by a neuroimaging approach and by a training protocol, Bin He and co-workers demonstrated the ability of a non-invasive EEG based brain-computer interface to control the flight of a virtual helicopter in 3-dimensional space, based upon motor imagination. In June 2013 it was announced that Bin He had developed the technique to enable a remote-control helicopter to be guided through an obstacle course.

In addition to a brain-computer interface based on brain waves, as recorded from scalp EEG electrodes, Bin He and co-workers explored a virtual EEG signal-based brain-computer interface by first solving the EEG inverse problem and then used the resulting virtual EEG for brain-computer interface tasks. Well-controlled studies suggested the merits of such a source analysis based brain-computer interface.

A 2014 study found that severely motor-impaired patients could communicate faster and more reliably with non-invasive EEG BCI, than with any muscle-based communication channel.

A 2016 study found that the Emotiv EPOC device may be more suitable for control tasks using the attention/meditation level or eye blinking than the Neurosky MindWave device.

A 2019 study found that the application of evolutionary algorithms could improve EEG mental state classification with a non-invasive Muse device, enabling high quality classification of data acquired by a cheap consumer-grade EEG sensing device.

Dry active electrode arrays

In the early 1990s Babak Taheri, at University of California, Davis demonstrated the first single and also multichannel dry active electrode arrays using micro-machining. The single channel dry EEG electrode construction and results were published in 1994. The arrayed electrode was also demonstrated to perform well compared to silver/silver chloride electrodes. The device consisted of four sites of sensors with integrated electronics to reduce noise by impedance matching. The advantages of such electrodes are: (1) no electrolyte used, (2) no skin preparation, (3) significantly reduced sensor size, and (4) compatibility with EEG monitoring systems. The active electrode array is an integrated system made of an array of capacitive sensors with local integrated circuitry housed in a package with batteries to power the circuitry. This level of integration was required to achieve the functional performance obtained by the electrode.

The electrode was tested on an electrical test bench and on human subjects in four modalities of EEG activity, namely: (1) spontaneous EEG, (2) sensory event-related potentials, (3) brain stem potentials, and (4) cognitive event-related potentials. The performance of the dry electrode compared favorably with that of the standard wet electrodes in terms of skin preparation, no gel requirements (dry), and higher signal-to-noise ratio.

In 1999 researchers at Case Western Reserve University, in Cleveland, Ohio, led by Hunter Peckham, used 64-electrode EEG skullcap to return limited hand movements to quadriplegic Jim Jatich. As Jatich concentrated on simple but opposite concepts like up and down, his beta-rhythm EEG output was analysed using software to identify patterns in the noise. A basic pattern was identified and used to control a switch: Above average activity was set to on, below average off. As well as enabling Jatich to control a computer cursor the signals were also used to drive the nerve controllers embedded in his hands, restoring some movement.

SSVEP mobile EEG BCIs

In 2009, the NCTU Brain-Computer-Interface-headband was reported. The researchers who developed this BCI-headband also engineered silicon-based MicroElectro-Mechanical System (MEMS) dry electrodes designed for application in non-hairy sites of the body. These electrodes were secured to the DAQ board in the headband with snap-on electrode holders. The signal processing module measured alpha activity and the Bluetooth enabled phone assessed the patients' alertness and capacity for cognitive performance. When the subject became drowsy, the phone sent arousing feedback to the operator to rouse them. This research was supported by the National Science Council, Taiwan, R.O.C., NSC, National Chiao-Tung University, Taiwan's Ministry of Education, and the U.S. Army Research Laboratory.

In 2011, researchers reported a cellular based BCI with the capability of taking EEG data and converting it into a command to cause the phone to ring. This research was supported in part by Abraxis Bioscience LLP, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, and the Army Research Office. The developed technology was a wearable system composed of a four channel bio-signal acquisition/amplification module, a wireless transmission module, and a Bluetooth enabled cell phone. The electrodes were placed so that they pick up steady state visual evoked potentials (SSVEPs). SSVEPs are electrical responses to flickering visual stimuli with repetition rates over 6 Hz that are best found in the parietal and occipital scalp regions of the visual cortex. It was reported that with this BCI setup, all study participants were able to initiate the phone call with minimal practice in natural environments.

The scientists claim that their studies using a single channel fast Fourier transform (FFT) and multiple channel system canonical correlation analysis (CCA) algorithm support the capacity of mobile BCIs. The CCA algorithm has been applied in other experiments investigating BCIs with claimed high performance in accuracy as well as speed. While the cellular based BCI technology was developed to initiate a phone call from SSVEPs, the researchers said that it can be translated for other applications, such as picking up sensorimotor mu/beta rhythms to function as a motor-imagery based BCI.

In 2013, comparative tests were performed on android cell phone, tablet, and computer based BCIs, analyzing the power spectrum density of resultant EEG SSVEPs. The stated goals of this study, which involved scientists supported in part by the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, were to "increase the practicability, portability, and ubiquity of an SSVEP-based BCI, for daily use". Citation It was reported that the stimulation frequency on all mediums was accurate, although the cell phone's signal demonstrated some instability. The amplitudes of the SSVEPs for the laptop and tablet were also reported to be larger than those of the cell phone. These two qualitative characterizations were suggested as indicators of the feasibility of using a mobile stimulus BCI.

Limitations

In 2011, researchers stated that continued work should address ease of use, performance robustness, reducing hardware and software costs.

One of the difficulties with EEG readings is the large susceptibility to motion artifacts. In most of the previously described research projects, the participants were asked to sit still, reducing head and eye movements as much as possible, and measurements were taken in a laboratory setting. However, since the emphasized application of these initiatives had been in creating a mobile device for daily use, the technology had to be tested in motion.

In 2013, researchers tested mobile EEG-based BCI technology, measuring SSVEPs from participants as they walked on a treadmill at varying speeds. This research was supported by the Office of Naval Research, Army Research Office, and the U.S. Army Research Laboratory. Stated results were that as speed increased the SSVEP detectability using CCA decreased. As independent component analysis (ICA) had been shown to be efficient in separating EEG signals from noise, the scientists applied ICA to CCA extracted EEG data. They stated that the CCA data with and without ICA processing were similar. Thus, they concluded that CCA independently demonstrated a robustness to motion artifacts that indicates it may be a beneficial algorithm to apply to BCIs used in real world conditions.

In 2020, researchers from the University of California used a computing system related to brain-machine interfaces to translate brainwaves into sentences. However, their decoding was limited to 30–50 sentences, even though the word error rates were as low as 3%.

Prosthesis and environment control

Non-invasive BCIs have also been applied to enable brain-control of prosthetic upper and lower extremity devices in people with paralysis. For example, Gert Pfurtscheller of Graz University of Technology and colleagues demonstrated a BCI-controlled functional electrical stimulation system to restore upper extremity movements in a person with tetraplegia due to spinal cord injury. Between 2012 and 2013, researchers at the University of California, Irvine demonstrated for the first time that it is possible to use BCI technology to restore brain-controlled walking after spinal cord injury. In their spinal cord injury research study, a person with paraplegia was able to operate a BCI-robotic gait orthosis to regain basic brain-controlled ambulation. In 2009 Alex Blainey, an independent researcher based in the UK, successfully used the Emotiv EPOC to control a 5 axis robot arm. He then went on to make several demonstration mind controlled wheelchairs and home automation that could be operated by people with limited or no motor control such as those with paraplegia and cerebral palsy.

Research into military use of BCIs funded by DARPA has been ongoing since the 1970s. The current focus of research is user-to-user communication through analysis of neural signals.

DIY and open source BCI

In 2001, The OpenEEG Project was initiated by a group of DIY neuroscientists and engineers. The ModularEEG was the primary device created by the OpenEEG community; it was a 6-channel signal capture board that cost between $200 and $400 to make at home. The OpenEEG Project marked a significant moment in the emergence of DIY brain-computer interfacing.

In 2010, the Frontier Nerds of NYU's ITP program published a thorough tutorial titled How To Hack Toy EEGs. The tutorial, which stirred the minds of many budding DIY BCI enthusiasts, demonstrated how to create a single channel at-home EEG with an Arduino and a Mattel Mindflex at a very reasonable price. This tutorial amplified the DIY BCI movement.

In 2013, OpenBCI emerged from a DARPA solicitation and subsequent Kickstarter campaign. They created a high-quality, open-source 8-channel EEG acquisition board, known as the 32bit Board, that retailed for under $500. Two years later they created the first 3D-printed EEG Headset, known as the Ultracortex, as well as a 4-channel EEG acquisition board, known as the Ganglion Board, that retailed for under $100.

MEG and MRI

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) have both been used successfully as non-invasive BCIs. In a widely reported experiment, fMRI allowed two users being scanned to play Pong in real-time by altering their haemodynamic response or brain blood flow through biofeedback techniques.

fMRI measurements of haemodynamic responses in real time have also been used to control robot arms with a seven-second delay between thought and movement.

In 2008 research developed in the Advanced Telecommunications Research (ATR) Computational Neuroscience Laboratories in Kyoto, Japan, allowed the scientists to reconstruct images directly from the brain and display them on a computer in black and white at a resolution of 10x10 pixels. The article announcing these achievements was the cover story of the journal Neuron of 10 December 2008.

In 2011 researchers from UC Berkeley published a study reporting second-by-second reconstruction of videos watched by the study's subjects, from fMRI data. This was achieved by creating a statistical model relating visual patterns in videos shown to the subjects, to the brain activity caused by watching the videos. This model was then used to look up the 100 one-second video segments, in a database of 18 million seconds of random YouTube videos, whose visual patterns most closely matched the brain activity recorded when subjects watched a new video. These 100 one-second video extracts were then combined into a mashed-up image that resembled the video being watched.

BCI control strategies in neurogaming

Motor imagery

Motor imagery involves the imagination of the movement of various body parts resulting in sensorimotor cortex activation, which modulates sensorimotor oscillations in the EEG. This can be detected by the BCI to infer a user's intent. Motor imagery typically requires a number of sessions of training before acceptable control of the BCI is acquired. These training sessions may take a number of hours over several days before users can consistently employ the technique with acceptable levels of precision. Regardless of the duration of the training session, users are unable to master the control scheme. This results in very slow pace of the gameplay. Advanced machine learning methods were recently developed to compute a subject-specific model for detecting the performance of motor imagery. The top performing algorithm from BCI Competition IV dataset 2 for motor imagery is the Filter Bank Common Spatial Pattern, developed by Ang et al. from A*STAR, Singapore).

Bio/neurofeedback for passive BCI designs

Biofeedback is used to monitor a subject's mental relaxation. In some cases, biofeedback does not monitor electroencephalography (EEG), but instead bodily parameters such as electromyography (EMG), galvanic skin resistance (GSR), and heart rate variability (HRV). Many biofeedback systems are used to treat certain disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), sleep problems in children, teeth grinding, and chronic pain. EEG biofeedback systems typically monitor four different bands (theta: 4–7 Hz, alpha:8–12 Hz, SMR: 12–15 Hz, beta: 15–18 Hz) and challenge the subject to control them. Passive BCI involves using BCI to enrich human–machine interaction with implicit information on the actual user's state, for example, simulations to detect when users intend to push brakes during an emergency car stopping procedure. Game developers using passive BCIs need to acknowledge that through repetition of game levels the user's cognitive state will change or adapt. Within the first play of a level, the user will react to things differently from during the second play: for example, the user will be less surprised at an event in the game if he/she is expecting it.

Visual evoked potential (VEP)

A VEP is an electrical potential recorded after a subject is presented with a type of visual stimuli. There are several types of VEPs.

Steady-state visually evoked potentials (SSVEPs) use potentials generated by exciting the retina, using visual stimuli modulated at certain frequencies. SSVEP's stimuli are often formed from alternating checkerboard patterns and at times simply use flashing images. The frequency of the phase reversal of the stimulus used can be clearly distinguished in the spectrum of an EEG; this makes detection of SSVEP stimuli relatively easy. SSVEP has proved to be successful within many BCI systems. This is due to several factors, the signal elicited is measurable in as large a population as the transient VEP and blink movement and electrocardiographic artefacts do not affect the frequencies monitored. In addition, the SSVEP signal is exceptionally robust; the topographic organization of the primary visual cortex is such that a broader area obtains afferents from the central or fovial region of the visual field. SSVEP does have several problems however. As SSVEPs use flashing stimuli to infer a user's intent, the user must gaze at one of the flashing or iterating symbols in order to interact with the system. It is, therefore, likely that the symbols could become irritating and uncomfortable to use during longer play sessions, which can often last more than an hour which may not be an ideal gameplay.

Another type of VEP used with applications is the P300 potential. The P300 event-related potential is a positive peak in the EEG that occurs at roughly 300 ms after the appearance of a target stimulus (a stimulus for which the user is waiting or seeking) or oddball stimuli. The P300 amplitude decreases as the target stimuli and the ignored stimuli grow more similar.The P300 is thought to be related to a higher level attention process or an orienting response using P300 as a control scheme has the advantage of the participant only having to attend limited training sessions. The first application to use the P300 model was the P300 matrix. Within this system, a subject would choose a letter from a grid of 6 by 6 letters and numbers. The rows and columns of the grid flashed sequentially and every time the selected "choice letter" was illuminated the user's P300 was (potentially) elicited. However, the communication process, at approximately 17 characters per minute, was quite slow. The P300 is a BCI that offers a discrete selection rather than a continuous control mechanism. The advantage of P300 use within games is that the player does not have to teach himself/herself how to use a completely new control system and so only has to undertake short training instances, to learn the gameplay mechanics and basic use of the BCI paradigm.

Synthetic telepathy/silent communication

In a $6.3million US Army initiative to invent devices for telepathic communication, Gerwin Schalk, underwritten in a $2.2 million grant, found the use of ECoG signals can discriminate the vowels and consonants embedded in spoken and imagined words, shedding light on the distinct mechanisms associated with production of vowels and consonants, and could provide the basis for brain-based communication using imagined speech.

In 2002 Kevin Warwick had an array of 100 electrodes fired into his nervous system in order to link his nervous system into the Internet to investigate enhancement possibilities. With this in place Warwick successfully carried out a series of experiments. With electrodes also implanted into his wife's nervous system, they conducted the first direct electronic communication experiment between the nervous systems of two humans.

Another group of researchers was able to achieve conscious brain-to-brain communication between two people separated by a distance using non-invasive technology that was in contact with the scalp of the participants. The words were encoded by binary streams using the sequences of 0's and 1's by the imaginary motor input of the person "emitting" the information. As the result of this experiment, pseudo-random bits of the information carried encoded words “hola” (“hi” in Spanish) and “ciao” (“hi” or “goodbye in Italian) and were transmitted mind-to-mind between humans separated by a distance, with blocked motor and sensory systems, which has little to no probability of this happening by chance.

Research into synthetic telepathy using subvocalization is taking place at the University of California, Irvine under lead scientist Mike D'Zmura. The first such communication took place in the 1960s using EEG to create Morse code using brain alpha waves. Using EEG to communicate imagined speech is less accurate than the invasive method of placing an electrode between the skull and the brain. On 27 February 2013 the group with Miguel Nicolelis at Duke University and IINN-ELS successfully connected the brains of two rats with electronic interfaces that allowed them to directly share information, in the first-ever direct brain-to-brain interface.

Cell-culture BCIs

Researchers have built devices to interface with neural cells and entire neural networks in cultures outside animals. As well as furthering research on animal implantable devices, experiments on cultured neural tissue have focused on building problem-solving networks, constructing basic computers and manipulating robotic devices. Research into techniques for stimulating and recording from individual neurons grown on semiconductor chips is sometimes referred to as neuroelectronics or neurochips.

Development of the first working neurochip was claimed by a Caltech team led by Jerome Pine and Michael Maher in 1997. The Caltech chip had room for 16 neurons.

In 2003 a team led by Theodore Berger, at the University of Southern California, started work on a neurochip designed to function as an artificial or prosthetic hippocampus. The neurochip was designed to function in rat brains and was intended as a prototype for the eventual development of higher-brain prosthesis. The hippocampus was chosen because it is thought to be the most ordered and structured part of the brain and is the most studied area. Its function is to encode experiences for storage as long-term memories elsewhere in the brain.

In 2004 Thomas DeMarse at the University of Florida used a culture of 25,000 neurons taken from a rat's brain to fly a F-22 fighter jet aircraft simulator. After collection, the cortical neurons were cultured in a petri dish and rapidly began to reconnect themselves to form a living neural network. The cells were arranged over a grid of 60 electrodes and used to control the pitch and yaw functions of the simulator. The study's focus was on understanding how the human brain performs and learns computational tasks at a cellular level.

Ethical considerations

User-centric issues

- Long-term effects to the user remain largely unknown.

- Obtaining informed consent from people who have difficulty communicating.

- The consequences of BCI technology for the quality of life of patients and their families.

- Health-related side-effects (e.g. neurofeedback of sensorimotor rhythm training is reported to affect sleep quality).

- Therapeutic applications and their potential misuse.

- Safety risks

- Non-convertibility of some of the changes made to the brain

Legal and social

- Issues of accountability and responsibility: claims that the influence of BCIs overrides free will and control over sensory-motor actions, claims that cognitive intention was inaccurately translated due to a BCI malfunction.

- Personality changes involved caused by deep-brain stimulation.

- Concerns regarding the state of becoming a "cyborg" - having parts of the body that are living and parts that are mechanical.

- Questions personality: what does it mean to be a human?

- Blurring of the division between human and machine and inability to distinguish between human vs. machine-controlled actions.

- Use of the technology in advanced interrogation techniques by governmental authorities.

- Selective enhancement and social stratification.

- Questions of research ethics that arise when progressing from animal experimentation to application in human subjects.

- Moral questions

- Mind reading and privacy.

- Tracking and "tagging system"

- Mind control.

- Movement control

- Emotion control

In their current form, most BCIs are far removed from the ethical issues considered above. They are actually similar to corrective therapies in function. Clausen stated in 2009 that "BCIs pose ethical challenges, but these are conceptually similar to those that bioethicists have addressed for other realms of therapy". Moreover, he suggests that bioethics is well-prepared to deal with the issues that arise with BCI technologies. Haselager and colleagues pointed out that expectations of BCI efficacy and value play a great role in ethical analysis and the way BCI scientists should approach media. Furthermore, standard protocols can be implemented to ensure ethically sound informed-consent procedures with locked-in patients.

The case of BCIs today has parallels in medicine, as will its evolution. Similar to how pharmaceutical science began as a balance for impairments and is now used to increase focus and reduce need for sleep, BCIs will likely transform gradually from therapies to enhancements. Efforts are made inside the BCI community to create consensus on ethical guidelines for BCI research, development and dissemination.

Low-cost BCI-based interfaces

Recently a number of companies have scaled back medical grade EEG technology (and in one case, NeuroSky, rebuilt the technology from the ground up) to create inexpensive BCIs. This technology has been built into toys and gaming devices; some of these toys have been extremely commercially successful like the NeuroSky and Mattel MindFlex.

- In 2006 Sony patented a neural interface system allowing radio waves to affect signals in the neural cortex.

- In 2007 NeuroSky released the first affordable consumer based EEG along with the game NeuroBoy. This was also the first large scale EEG device to use dry sensor technology.

- In 2008 OCZ Technology developed a device for use in video games relying primarily on electromyography.

- In 2008 Final Fantasy developer Square Enix announced that it was partnering with NeuroSky to create a game, Judecca.

- In 2009 Mattel partnered with NeuroSky to release the Mindflex, a game that used an EEG to steer a ball through an obstacle course. It is by far the best selling consumer based EEG to date.

- In 2009 Uncle Milton Industries partnered with NeuroSky to release the Star Wars Force Trainer, a game designed to create the illusion of possessing the Force .

- In 2009 Emotiv released the EPOC, a 14 channel EEG device that can read 4 mental states, 13 conscious states, facial expressions, and head movements. The EPOC is the first commercial BCI to use dry sensor technology, which can be dampened with a saline solution for a better connection.

- In November 2011 Time Magazine selected "necomimi" produced by Neurowear as one of the best inventions of the year. The company announced that it expected to launch a consumer version of the garment, consisting of cat-like ears controlled by a brain-wave reader produced by NeuroSky, in spring 2012.

- In February 2014 They Shall Walk (a nonprofit organization fixed on constructing exoskeletons, dubbed LIFESUITs, for paraplegics and quadriplegics) began a partnership with James W. Shakarji on the development of a wireless BCI.

- In 2016, a group of hobbyists developed an open-source BCI board that sends neural signals to the audio jack of a smartphone, dropping the cost of entry-level BCI to £20. Basic diagnostic software is available for Android devices, as well as a text entry app for Unity.

Future directions

A consortium consisting of 12 European partners has completed a roadmap to support the European Commission in their funding decisions for the new framework program Horizon 2020. The project, which was funded by the European Commission, started in November 2013 and published a roadmap in April 2015. A 2015 publication led by Dr. Clemens Brunner describes some of the analyses and achievements of this project, as well as the emerging Brain-Computer Interface Society. For example, this article reviewed work within this project that further defined BCIs and applications, explored recent trends, discussed ethical issues, and evaluated different directions for new BCIs. As the article notes, their new roadmap generally extends and supports the recommendations from the Future BNCI project managed by Dr. Brendan Allison, which conveys substantial enthusiasm for emerging BCI directions.

Other recent publications too have explored future BCI directions for new groups of disabled users. Some prominent examples are summarized below.

Disorders of consciousness (DOC)

Some persons have a disorder of consciousness (DOC). This state is defined to include persons with coma, as well as persons in a vegetative state (VS) or minimally conscious state (MCS). New BCI research seeks to help persons with DOC in different ways. A key initial goal is to identify patients who are able to perform basic cognitive tasks, which would of course lead to a change in their diagnosis. That is, some persons who are diagnosed with DOC may in fact be able to process information and make important life decisions (such as whether to seek therapy, where to live, and their views on end-of-life decisions regarding them). Some persons who are diagnosed with DOC die as a result of end-of-life decisions, which may be made by family members who sincerely feel this is in the patient's best interests. Given the new prospect of allowing these patients to provide their views on this decision, there would seem to be a strong ethical pressure to develop this research direction to guarantee that DOC patients are given an opportunity to decide whether they want to live.

These and other articles describe new challenges and solutions to use BCI technology to help persons with DOC. One major challenge is that these patients cannot use BCIs based on vision. Hence, new tools rely on auditory and/or vibrotactile stimuli. Patients may wear headphones and/or vibrotactile stimulators placed on the wrists, neck, leg, and/or other locations. Another challenge is that patients may fade in and out of consciousness, and can only communicate at certain times. This may indeed be a cause of mistaken diagnosis. Some patients may only be able to respond to physicians' requests during a few hours per day (which might not be predictable ahead of time) and thus may have been unresponsive during diagnosis. Therefore, new methods rely on tools that are easy to use in field settings, even without expert help, so family members and other persons without any medical or technical background can still use them. This reduces the cost, time, need for expertise, and other burdens with DOC assessment. Automated tools can ask simple questions that patients can easily answer, such as "Is your father named George?" or "Were you born in the USA?" Automated instructions inform patients that they may convey yes or no by (for example) focusing their attention on stimuli on the right vs. left wrist. This focused attention produces reliable changes in EEG patterns that can help determine that the patient is able to communicate. The results could be presented to physicians and therapists, which could lead to a revised diagnosis and therapy. In addition, these patients could then be provided with BCI-based communication tools that could help them convey basic needs, adjust bed position and HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning), and otherwise empower them to make major life decisions and communicate.

Motor recovery

People may lose some of their ability to move due to many causes, such as stroke or injury. Several groups have explored systems and methods for motor recovery that include BCIs. In this approach, a BCI measures motor activity while the patient imagines or attempts movements as directed by a therapist. The BCI may provide two benefits: (1) if the BCI indicates that a patient is not imagining a movement correctly (non-compliance), then the BCI could inform the patient and therapist; and (2) rewarding feedback such as functional stimulation or the movement of a virtual avatar also depends on the patient's correct movement imagery.

So far, BCIs for motor recovery have relied on the EEG to measure the patient's motor imagery. However, studies have also used fMRI to study different changes in the brain as persons undergo BCI-based stroke rehab training. Future systems might include the fMRI and other measures for real-time control, such as functional near-infrared, probably in tandem with EEGs. Non-invasive brain stimulation has also been explored in combination with BCIs for motor recovery. In 2016, scientists out of the University of Melbourne published preclinical proof-of-concept data related to a potential brain-computer interface technology platform being developed for patients with paralysis to facilitate control of external devices such as robotic limbs, computers and exoskeletons by translating brain activity. Clinical trials are currently underway.

Functional brain mapping

Each year, about 400,000 people undergo brain mapping during neurosurgery. This procedure is often required for people with tumors or epilepsy that do not respond to medication. During this procedure, electrodes are placed on the brain to precisely identify the locations of structures and functional areas. Patients may be awake during neurosurgery and asked to perform certain tasks, such as moving fingers or repeating words. This is necessary so that surgeons can remove only the desired tissue while sparing other regions, such as critical movement or language regions. Removing too much brain tissue can cause permanent damage, while removing too little tissue can leave the underlying condition untreated and require additional neurosurgery. Thus, there is a strong need to improve both methods and systems to map the brain as effectively as possible.

In several recent publications, BCI research experts and medical doctors have collaborated to explore new ways to use BCI technology to improve neurosurgical mapping. This work focuses largely on high gamma activity, which is difficult to detect with non-invasive means. Results have led to improved methods for identifying key areas for movement, language, and other functions. A recent article addressed advances in functional brain mapping and summarizes a workshop.

Flexible devices

Flexible electronics are polymers or other flexible materials (e.g. silk, pentacene, PDMS, Parylene, polyimide) that are printed with circuitry; the flexible nature of the organic background materials allowing the electronics created to bend, and the fabrication techniques used to create these devices resembles those used to create integrated circuits and microelectromechanical systems (MEMS). Flexible electronics were first developed in the 1960s and 1970s, but research interest increased in the mid-2000s.

Neural dust

Neural dust is a term used to refer to millimeter-sized devices operated as wirelessly powered nerve sensors that were proposed in a 2011 paper from the University of California, Berkeley Wireless Research Center, which described both the challenges and outstanding benefits of creating a long lasting wireless BCI. In one proposed model of the neural dust sensor, the transistor model allowed for a method of separating between local field potentials and action potential "spikes", which would allow for a greatly diversified wealth of data acquirable from the recordings.