Senescence (/sɪˈnɛsəns/) or biological aging is the gradual deterioration of functional characteristics. The word senescence can refer either to cellular senescence or to senescence of the whole organism. Organismal senescence involves an increase in death rates and/or a decrease in fecundity with increasing age, at least in the latter part of an organism's life cycle.

Senescence is the inevitable fate of all multicellular organisms with germ-soma separation, but it can be delayed. The discovery, in 1934, that calorie restriction can extend lifespan by 50% in rats, and the existence of species having negligible senescence and potentially immortal organisms such as Hydra, have motivated research into delaying senescence and thus age-related diseases. Rare human mutations can cause accelerated aging diseases.

Environmental factors may affect aging, for example, overexposure to ultraviolet radiation accelerates skin aging. Different parts of the body may age at different rates. Two organisms of the same species can also age at different rates, making biological aging and chronological aging distinct concepts.

Definition and characteristics

Organismal senescence is the aging of whole organisms. Actuarial senescence can be defined as an increase in mortality and/or a decrease in fecundity with age. The Gompertz–Makeham law of mortality says that the age-dependent component of the mortality rate increases exponentially with age.

In 2013, a group of scientists defined nine hallmarks of aging that are common between organisms with emphasis on mammals:

- genomic instability,

- telomere attrition,

- epigenetic alterations,

- loss of proteostasis,

- deregulated nutrient sensing,

- mitochondrial dysfunction,

- cellular senescence,

- stem cell exhaustion,

- altered intercellular communication.

Aging is characterized by the declining ability to respond to stress, increased homeostatic imbalance, and increased risk of aging-associated diseases including cancer and heart disease. Aging has been defined as "a progressive deterioration of physiological function, an intrinsic age-related process of loss of viability and increase in vulnerability."

The environment induces damage at various levels, e.g. damage to DNA, and damage to tissues and cells by oxygen radicals (widely known as free radicals), and some of this damage is not repaired and thus accumulates with time. Cloning from somatic cells rather than germ cells may begin life with a higher initial load of damage. Dolly the sheep died young from a contagious lung disease, but data on an entire population of cloned individuals would be necessary to measure mortality rates and quantify aging.

The evolutionary theorist George Williams wrote, "It is remarkable that after a seemingly miraculous feat of morphogenesis, a complex metazoan should be unable to perform the much simpler task of merely maintaining what is already formed."

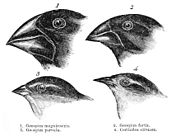

Variation among species

Different speeds with which mortality increases with age correspond to different maximum life span among species. For example, a mouse is elderly at 3 years, a human is elderly at 80 years, and gingko trees show little effect of age even at 667 years.

Almost all organisms senesce, including bacteria which have asymmetries between "mother" and "daughter" cells upon cell division, with the mother cell experiencing aging, while the daughter is rejuvenated. There is negligible senescence in some groups, such as the genus Hydra. Planarian flatworms have "apparently limitless telomere regenerative capacity fueled by a population of highly proliferative adult stem cells." These planarians are not biologically immortal, but rather their death rate slowly increases with age. Organisms that are thought be biologically immortal would, in one instance, be the Turritopsis dohrnii, also known as the immortal jellyfish. The Turritopsis dohrnii received such a title by having the ability to revert to its youth when it undergoes stress during adulthood. The reproductive system is observed to remain intact, and even the gonads of the Turritopsis dohrnii are existing.

Some species exhibit "negative senescence", in which reproduction capability increases or is stable, and mortality falls with age, resulting from the advantages of increased body size during aging.

Evolutionary theories of aging

Mutation accumulation

Natural selection can support lethal and harmful alleles, if their effects are felt after reproduction. The geneticist J. B. S. Haldane wondered why the dominant mutation that causes Huntington's disease remained in the population, and why natural selection had not eliminated it. The onset of this neurological disease is (on average) at age 45 and is invariably fatal within 10–20 years. Haldane assumed that, in human prehistory, few survived until age 45. Since few were alive at older ages and their contribution to the next generation was therefore small relative to the large cohorts of younger age groups, the force of selection against such late-acting deleterious mutations was correspondingly small. Therefore, a genetic load of late-acting deleterious mutations could be substantial at mutation–selection balance. This concept came to be known as the selection shadow.

Peter Medawar formalised this observation in his mutation accumulation theory of aging. "The force of natural selection weakens with increasing age—even in a theoretically immortal population, provided only that it is exposed to real hazards of mortality. If a genetic disaster... happens late enough in individual life, its consequences may be completely unimportant". The 'real hazards of mortality' such as predation, disease, and accidents, are known 'extrinsic mortality', and mean that even a population with negligible senescence will have fewer individuals alive in older age groups.

Antagonistic pleiotropy

Another evolutionary theory of aging was proposed by George C. Williams and involves antagonistic pleiotropy. A single gene may affect multiple traits. Some traits that increase fitness early in life may also have negative effects later in life. But, because many more individuals are alive at young ages than at old ages, even small positive effects early can be strongly selected for, and large negative effects later may be very weakly selected against. Williams suggested the following example: Perhaps a gene codes for calcium deposition in bones, which promotes juvenile survival and will therefore be favored by natural selection; however, this same gene promotes calcium deposition in the arteries, causing negative atherosclerotic effects in old age. Thus, harmful biological changes in old age may result from selection for pleiotropic genes that are beneficial early in life but harmful later on. In this case, selection pressure is relatively high when Fisher's reproductive value is high and relatively low when Fisher's reproductive value is low.

Adaptive aging

Programmed theories of aging posit that aging is adaptive, normally invoking selection for evolvability or group selection.

The reproductive-cell cycle theory suggests that aging is regulated by changes in hormonal signaling over the lifespan.

Disposable soma

The disposable soma theory of aging was proposed by Thomas Kirkwood in 1977. The theory suggests that aging occurs due to a strategy in which an individual only invests in maintenance of the soma for as long as it has a realistic chance of survival. A species that uses resources more efficiently will live longer, and therefore be able to pass on genetic information to the next generation. The demands of reproduction are high, so less effort is invested in repair and maintenance of somatic cells, compared to germline cells, in order to focus on reproduction and species survival.

Cellular senescence

(upper) Primary mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (MEFs) before senescence. Spindle-shaped. (lower) MEFs became senescent after passages. Cells grow larger, flatten shape and expressed senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SABG, blue areas), a marker of cellular senescence.

Cells accumulate damage over time. In particular DNA damage, e.g. due to reactive oxygen species, leads to the accumulation of harmful somatic mutations.

The cellular senescence theory of aging posits that organismal aging is a consequence of the accumulation of less physiologically useful, i.e. senescent cells. In agreement with this, the experimental elimination of senescent cells from transgenic progeroid mice and non-progeroid, naturally-aged mice led to greater resistance against aging-associated diseases. Ectopic expression of the embryonic transcription factor, NANOG, is shown to reverse senescence and restore the proliferation and differentiation potential of senescent stem cells.

In many organisms, there is asymmetric cell division, e.g. a stem cell dividing to produce one stem cell and one non-stem cell. The cellular debris that cells accumulate is not evenly divided between the new cells when they divide. Instead more of the damage is passed to one of the cells, leaving the other cell rejuvenated. One lineage then undergoes cellular senescence faster than the other.

Natural selection can remove damaged cells and prevent their proliferation, counterbalancing the natural tendency for damaged cells to accumulate. However, some cells mutate in ways that escape these control mechanisms. Cancer cells avoid replicative senescence to become immortal. In about 85% of tumors, this evasion of cellular senescence is the result of up-activation of their telomerase genes.

In most multicellular species, somatic cells eventually experience replicative senescence and are unable to divide. This can prevent highly mutated cells from becoming cancerous. In culture, fibroblasts can reach a maximum of 50 cell divisions; this maximum is known as the Hayflick limit. Replicative senescence is the result of telomere shortening that ultimately triggers a DNA damage response. Cells can also be induced to senesce via DNA damage in response to elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS), activation of oncogenes and cell-cell fusion, independent of telomere length.

Cancer versus cellular senescence tradeoff theory of aging

Senescent cells within a multicellular organism can be purged by competition between cells, but this increases the risk of cancer. This leads to an inescapable dilemma between two possibilities—the accumulation of physiologically useless senescent cells, and cancer—both of which lead to increasing rates of mortality with age.

Chemical damage

One of the earliest aging theories was the Rate of Living Hypothesis described by Raymond Pearl in 1928 (based on earlier work by Max Rubner), which states that fast basal metabolic rate corresponds to short maximum life span.

While there may be some validity to the idea that for various types of specific damage detailed below that are by-products of metabolism, all other things being equal, a fast metabolism may reduce lifespan, in general this theory does not adequately explain the differences in lifespan either within, or between, species. Calorically restricted animals process as much, or more, calories per gram of body mass, as their ad libitum fed counterparts, yet exhibit substantially longer lifespans. Similarly, metabolic rate is a poor predictor of lifespan for birds, bats and other species that, it is presumed, have reduced mortality from predation, and therefore have evolved long lifespans even in the presence of very high metabolic rates. In a 2007 analysis it was shown that, when modern statistical methods for correcting for the effects of body size and phylogeny are employed, metabolic rate does not correlate with longevity in mammals or birds. (For a critique of the Rate of Living Hypothesis see Living fast, dying when?)

With respect to specific types of chemical damage caused by metabolism, it is suggested that damage to long-lived biopolymers, such as structural proteins or DNA, caused by ubiquitous chemical agents in the body such as oxygen and sugars, are in part responsible for aging. The damage can include breakage of biopolymer chains, cross-linking of biopolymers, or chemical attachment of unnatural substituents (haptens) to biopolymers. Under normal aerobic conditions, approximately 4% of the oxygen metabolized by mitochondria is converted to superoxide ion, which can subsequently be converted to hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical and eventually other reactive species including other peroxides and singlet oxygen, which can, in turn, generate free radicals capable of damaging structural proteins and DNA. Certain metal ions found in the body, such as copper and iron, may participate in the process. (In Wilson's disease, a hereditary defect that causes the body to retain copper, some of the symptoms resemble accelerated senescence.) These processes termed oxidative stress are linked to the potential benefits of dietary polyphenol antioxidants, for example in coffee, red wine and tea.

Sugars such as glucose and fructose can react with certain amino acids such as lysine and arginine and certain DNA bases such as guanine to produce sugar adducts, in a process called glycation. These adducts can further rearrange to form reactive species, which can then cross-link the structural proteins or DNA to similar biopolymers or other biomolecules such as non-structural proteins. People with diabetes, who have elevated blood sugar, develop senescence-associated disorders much earlier than the general population, but can delay such disorders by rigorous control of their blood sugar levels. There is evidence that sugar damage is linked to oxidant damage in a process termed glycoxidation.

Free radicals can damage proteins, lipids or DNA. Glycation mainly damages proteins. Damaged proteins and lipids accumulate in lysosomes as lipofuscin. Chemical damage to structural proteins can lead to loss of function; for example, damage to collagen of blood vessel walls can lead to vessel-wall stiffness and, thus, hypertension, and vessel wall thickening and reactive tissue formation (atherosclerosis); similar processes in the kidney can lead to kidney failure. Damage to enzymes reduces cellular functionality. Lipid peroxidation of the inner mitochondrial membrane reduces the electric potential and the ability to generate energy. It is probably no accident that nearly all of the so-called "accelerated aging diseases" are due to defective DNA repair enzymes.

It is believed that the impact of alcohol on aging can be partly explained by alcohol's activation of the HPA axis, which stimulates glucocorticoid secretion, long-term exposure to which produces symptoms of aging.

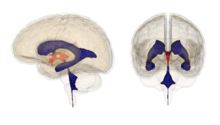

Biomarkers of aging

If different individuals age at different rates, then fecundity, mortality, and functional capacity might be better predicted by biomarkers than by chronological age. However, graying of hair, skin wrinkles and other common changes seen with aging are not better indicators of future functionality than chronological age. Biogerontologists have continued efforts to find and validate biomarkers of aging, but success thus far has been limited. Levels of CD4 and CD8 memory T cells and naive T cells have been used to give good predictions of the expected lifespan of middle-aged mice.

There is interest in an epigenetic clock as a biomarker of aging, based on its ability to predict human chronological age. Basic blood biochemistry and cell counts can also be used to accurately predict the chronological age. It is also possible to predict the human chronological age using the transcriptomic aging clocks.

Genetic determinants of aging

A number of genetic components of aging have been identified using model organisms, ranging from the simple budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae to worms such as Caenorhabditis elegans and fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster). Study of these organisms has revealed the presence of at least two conserved aging pathways.

Gene expression is imperfectly controlled, and it is possible that random fluctuations in the expression levels of many genes contribute to the aging process as suggested by a study of such genes in yeast. Individual cells, which are genetically identical, nonetheless can have substantially different responses to outside stimuli, and markedly different lifespans, indicating that epigenetic factors play an important role in gene expression and aging as well as genetic factors.

The ability to repair DNA double-strand breaks declines with aging in mice and humans.

A set of rare hereditary (genetics) disorders, each called progeria, has been known for some time. Sufferers exhibit symptoms resembling accelerated aging, including wrinkled skin. The cause of Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome was reported in the journal Nature in May 2003. This report suggests that DNA damage, not oxidative stress, is the cause of this form of accelerated aging.