Buddhist cosmology is the description of the shape and evolution of the Universe according to the Buddhist scriptures and commentaries.

It consists of temporal and spatial cosmology: the temporal cosmology being the division of the existence of a 'world' into four discrete moments (the creation, duration, dissolution, and state of being dissolved; this does not seem to be a canonical division, however). The spatial cosmology consists of a vertical cosmology, the various planes of beings, their bodies, characteristics, food, lifespan, beauty and a horizontal cosmology, the distribution of these world-systems into an "apparently" infinite sheet of “worlds”. The existence of world-periods (moments, kalpas), is well attested to by the Buddha.

The historical Buddha (Gautama Buddha) made references to the existence of aeons (the duration of which he describes using a metaphor of the time taken to erode a huge rock measuring 1x1x1 mile by brushing it with a silk cloth, once every century), and simultaneously intimates his knowledge of past events, such as the dawn of human beings in their coarse and gender-split forms, the existence of more than one sun at certain points in time, and his ability to convey his voice vast distances, as well as the ability of his disciples (who if they fare accordingly) to be reborn in any one of these planes (should they so choose).

Introduction

The self-consistent Buddhist cosmology, which is presented in commentaries and works of Abhidharma in both Theravāda and Mahāyāna traditions, is the end-product of an analysis and reconciliation of cosmological comments found in the Buddhist sūtra and vinaya traditions. No single sūtra sets out the entire structure of the universe, but in several sūtras the Buddha describes other worlds and states of being, and other sūtras describe the origin and destruction of the universe. The synthesis of these data into a single comprehensive system must have taken place early in the history of Buddhism, as the system described in the Pāli Vibhajyavāda tradition (represented by today's Theravādins) agrees, despite some minor inconsistencies of nomenclature, with the Sarvāstivāda tradition which is preserved by Mahāyāna Buddhists.

The picture of the world presented in Buddhist cosmological descriptions cannot be taken as a literal description of the shape of the universe. It is inconsistent, and cannot be made consistent, with astronomical data that were already known in ancient India. However, it is not intended to be a description of how ordinary humans perceive their world; rather, it is the universe as seen through the divyacakṣus दिव्यचक्षुः (Pāli: dibbacakkhu दिब्बचक्खु), the "divine eye" by which a Buddha or an arhat who has cultivated this faculty can perceive all of the other worlds and the beings arising (being born) and passing away (dying) within them, and can tell from what state they have been reborn and into what state they will be reborn. The cosmology has also been interpreted in a symbolical or allegorical sense (for Mahayana teaching see Ten spiritual realms).

Buddhist cosmology can be divided into two related kinds: spatial cosmology, which describes the arrangement of the various worlds within the universe; and temporal cosmology, which describes how those worlds come into existence, and how they pass away.

Spatial cosmology

Spatial cosmology displays the various, multitude of worlds embedded in the universe. Spatial cosmology can also be divided into two branches. The vertical (or cakravāḍa; Devanagari: चक्रवाड) cosmology describes the arrangement of worlds in a vertical pattern, some being higher and some lower. By contrast, the horizontal (sahasra) cosmology describes the grouping of these vertical worlds into sets of thousands, millions or billions.

Vertical cosmology

"In the vertical cosmology, the universe exists of many worlds (lokāḥ; Devanagari: लोकाः) – one might say "planes/realms" – stacked one upon the next in layers. Each world corresponds to a mental state or a state of being". A world is not, however, a location so much as it is the beings which compose it; it is sustained by their karma and if the beings in a world all die or disappear, the world disappears too. Likewise, a world comes into existence when the first being is born into it. The physical separation is not so important as the difference in mental state; humans and animals, though they partially share the same physical environments, still belong to different worlds because their minds perceive and react to those environments differently.

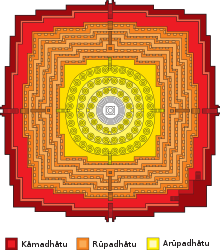

The vertical cosmology is divided into thirty-one planes of existence and the planes into three realms, or dhātus, each corresponding to a different type of mentality. These three realms (Tridhātu) are the Ārūpyadhātu (4 Realms), the Rūpadhātu (16 Realms), and the Kāmadhātu (15 Realms). In some instances all of the beings born in the Ārūpyadhātu and the Rūpadhātu are informally classified as "gods" or "deities" (devāḥ), along with the gods of the Kāmadhātu, notwithstanding the fact that the deities of the Kāmadhātu differ more from those of the Ārūpyadhātu than they do from humans. It is to be understood that deva is an imprecise term referring to any being living in a longer-lived and generally more blissful state than humans. Most of them are not "gods" in the common sense of the term, having little or no concern with the human world and rarely if ever interacting with it; only the lowest deities of the Kāmadhātu correspond to the gods described in many polytheistic religions.

The term "brahmā; Devanagari: ब्रह्मा" is used both as a name and as a generic term for one of the higher devas. In its broadest sense, it can refer to any of the inhabitants of the Ārūpyadhātu and the Rūpadhātu. In more restricted senses, it can refer to an inhabitant of one of the eleven lower worlds of the Rūpadhātu, or in its narrowest sense, to the three lowest worlds of the Rūpadhātu (Plane of Brahma's retinue) A large number of devas use the name "Brahmā", e.g. Brahmā Sahampati ब्रह्मा सहम्पत्ति, Brahmā Sanatkumāra ब्रह्मा सनत्कुमारः, Baka Brahmā बकब्रह्मा, etc. It is not always clear which world they belong to, although it must always be one of the worlds of the Rūpadhātu. According to the Ayacana Sutta, Brahmā Sahampati, who begs the Buddha to teach Dhamma to the world, resides in the Śuddhāvāsa worlds.

Formless Realm (Ārūpyadhātu आरूपधातु)

The Ārūpyadhātu (Sanskrit) or Arūpaloka (Pāli) (Tib: gzugs med pa'i khams; Chinese: 无色界/無色界;Jpn: 無色界 Mushiki-kai; Burmese: အရူပဗြဟ္မာဘုံ;Thai: อารูปยธาตุ/ อรูปโลก; Devanagari: आरूप्यधातु / अरूपलोक) or "Formless realm" would have no place in a purely physical cosmology, as none of the beings inhabiting it has either shape or location; and correspondingly, the realm has no location either. This realm belongs to those devas who attained and remained in the Four Formless Absorptions (catuḥ-samāpatti चतुःसमापत्ति) of the arūpadhyānas in a previous life, and now enjoys the fruits (vipāka) of the good karma of that accomplishment. Bodhisattvas, however, are never born in the Ārūpyadhātu even when they have attained the arūpadhyānas.

There are four types of Ārūpyadhātu devas, corresponding to the four types of arūpadhyānas:

Arupa Bhumi (Arupachara Brahmalokas or Immaterial/Formless Brahma Realms)

- Naivasaṃjñānāsaṃjñāyatana नैवसंज्ञानासंज्ञायतन or Nevasaññānāsaññāyatana नेवसञ्ञानासञ्ञायतन (Tib: 'du shes med 'du shes med min; Jpn: 非有想非無想処; Burmese: နေဝသညာ နာသညာယတန; Thai: เนวสญฺญานาสญฺญายตน or ไนวสํชญานาสํชญายตน ) "Sphere of neither perception nor non-perception". In this sphere the formless beings have gone beyond a mere negation of perception and have attained a liminal state where they do not engage in "perception" (saṃjñā, recognition of particulars by their marks) but are not wholly unconscious. This was the sphere reached by Udraka Rāmaputra (Pāli: Uddaka Rāmaputta), the second of the Buddha's original teachers, who considered it equivalent to enlightenment. Total life span on this realm in human years - 84,000 Maha Kalpa (Maha Kalpa = 4 Asankya Kalpa). This realm is placed 5,580,000 Yojanas ( 1 Yojana = 16 Miles) above the Plane of Nothingness (Ākiṃcanyāyatana).

- Ākiṃcanyāyatana आकिंचन्यायतना or Ākiñcaññāyatana आकिञ्चञ्ञायतन (Tib: ci yang med; Chinese: 无所有处/無所有處; Jpn: 無所有処 mu sho u sho; Burmese: အာကိဉ္စညာယတန; Thai: อากิญฺจญฺญายตน or อากิํจนฺยายตน; Devanagari: /) "Sphere of Nothingness" (literally "lacking anything"). In this sphere formless beings dwell contemplating upon the thought that "there is no thing". This is considered a form of perception, though a very subtle one. This was the sphere reached by Ārāḍa Kālāma (Pāli: Āḷāra Kālāma), the first of the Buddha's original teachers; he considered it to be equivalent to enlightenment. Total life span on this realm in human years – 60,000 Maha Kalpa. This realm is placed 5,580,000 yojanas above the Plane of Infinite Consciousness(Vijñānānantyāyatana).

- Vijñānānantyāyatana विज्ञानानन्त्यायतन or Viññāṇānañcāyatana विञ्ञाणानञ्चायतन or more commonly the contracted form Viññāṇañcāyatana (Tib: rnam shes mtha' yas; Chinese: 识无边处/識無邊處; Jpn: 識無辺処 shiki mu hen jo; Burmese: ဝိညာဏဉ္စာယတန; Thai: วิญญาณานญฺจายตน or วิชญานานนฺตยายตน) "Sphere of Infinite Consciousness". In this sphere formless beings dwell meditating on their consciousness (vijñāna) as infinitely pervasive. Total life span on this realm in human years – 40,000 Maha Kalpa. This realm is placed 5,580,000 yojanas above the Plane of Infinite Space (Ākāśānantyāyatana)

- Ākāśānantyāyatana अाकाशानन्त्यायतन or Ākāsānañcāyatana आकासानञ्चायतन (Tib: nam mkha' mtha' yas; Chinese: 空无边处/空無邊處;Jpn: 空無辺処 kū mu hen jo; Burmese: အာကာသာနဉ္စာယတန; Thai: อากาสานญฺจายตน or อากาศานนฺตยายตน) "Sphere of Infinite Space". In this sphere formless beings dwell meditating upon space or extension (ākāśa) as infinitely pervasive. Total life span on this realm in human years – 20,000 Maha Kalpa. This realm is placed 5,580,000 yojanas above the Akanita Brahma Loka – Highest plane of pure abodes.

Form Realm (Rūpadhātu)

The Rūpadhātu रूपधातुः (Pāli: Rūpaloka रूपलोक; Tib: gzugs kyi khams; Chinese: 色界; Jpn: 色界 Shiki-kai; Burmese: ရူပဗြဟ္မာဘုံ; Thai: รูปโลก / รูปธาตุ) or "Form realm" is, as the name implies, the first of the physical realms; its inhabitants all have a location and bodies of a sort, though those bodies are composed of a subtle substance which is of itself invisible to the inhabitants of the Kāmadhātu. According to the Janavasabha Sutta, when a brahma (a being from the Brahma-world of the Rūpadhātu) wishes to visit a deva of the Trāyastriṃśa heaven (in the Kāmadhātu), he has to assume a "grosser form" in order to be visible to them. There are 17–22 Rūpadhātu in Buddhism texts, the most common saying is 18.

The beings of the Form realm are not subject to the extremes of pleasure and pain, or governed by desires for things pleasing to the senses, as the beings of the Kāmadhātu are. The bodies of Form realm beings do not have sexual distinctions.

Like the beings of the Ārūpyadhātu, the dwellers in the Rūpadhātu have minds corresponding to the dhyānas (Pāli: jhānas). In their case it is the four lower dhyānas or rūpadhyānas (रुपध्यान). However, although the beings of the Rūpadhātu can be divided into four broad grades corresponding to these four dhyānas, each of them is subdivided into further grades, three for each of the four dhyānas and five for the Śuddhāvāsa devas, for a total of seventeen grades (the Theravāda tradition counts one less grade in the highest dhyāna for a total of sixteen).

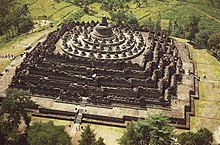

Physically, the Rūpadhātu consists of a series of planes stacked on top of each other, each one in a series of steps half the size of the previous one as one descends. In part, this reflects the fact that the devas are also thought of as physically larger on the higher planes. The highest planes are also broader in extent than the ones lower down, as discussed in the section on Sahasra cosmology. The height of these planes is expressed in yojanas, a measurement of very uncertain length, but sometimes taken to be about 4,000 times the height of a man, and so approximately 4.54 miles (7.31 km).

Pure Abodes

The Śuddhāvāsa शुद्धावास (Pāli: Suddhāvāsa सुद्धावास; Tib: gnas gtsang ma; Chinese: 净居天/凈居天; Thai: สุทฺธาวสฺสภูมิ) worlds, or "Pure Abodes", are distinct from the other worlds of the Rūpadhātu in that they do not house beings who have been born there through ordinary merit or meditative attainments, but only those Anāgāmins ("Non-returners") who are already on the path to Arhat-hood and who will attain enlightenment directly from the Śuddhāvāsa worlds without being reborn in a lower plane. Every Śuddhāvāsa deva is therefore a protector of Buddhism. (Brahma Sahampati, who appealed to the newly enlightened Buddha to teach, was an Anagami under the previous Buddha). Because a Śuddhāvāsa deva will never be reborn outside the Śuddhāvāsa worlds, no Bodhisattva is ever born in these worlds, as a Bodhisattva must ultimately be reborn as a human being.

Since these devas rise from lower planes only due to the teaching of a Buddha, they can remain empty for very long periods if no Buddha arises. However, unlike the lower worlds, the Śuddhāvāsa worlds are never destroyed by natural catastrophe. The Śuddhāvāsa devas predict the coming of a Buddha and, taking the guise of Brahmins, reveal to human beings the signs by which a Buddha can be recognized. They also ensure that a Bodhisattva in his last life will see the four signs that will lead to his renunciation.

The five Śuddhāvāsa worlds are:

- Akaniṣṭha अकनिष्ठ or Akaniṭṭha अकनिठ्ठ (Thai: อกนิฏฺฐา or อกนิษฐา)– World of devas "equal in rank" (literally: having no one as the youngest). The highest of all the Rūpadhātu worlds, it is often used to refer to the highest extreme of the universe. The current Śakra will eventually be born there. The duration of life in Akaniṣṭha is 16,000 kalpas (Vibhajyavāda tradition). Mahesvara (Shiva) the ruler of the three realms of samsara is said to dwell here. The height of this world is 167,772,160 yojanas above the Earth (approximately the distance of Saturn from Earth).

- Sudarśana सुदर्शन or Sudassī सुदस्सी (Thai: สุทัสสี or สุทารฺศฺน)– The "clear-seeing" devas live in a world similar to and friendly with the Akaniṣṭha world. The height of this world is 83,886,080 yojanas above the Earth (approximately the distance of Jupiter from Earth).

- Sudṛśa सुदृश or Sudassa सुदस्स (Thai: สุทัสสา or สุทรรศา)– The world of the "beautiful" devas are said to be the place of rebirth for five kinds of anāgāmins. The height of this world is 41,943,040 yojanas above the Earth.

- Atapa अतप or Atappa अतप्प (Thai: อตัปปา or อตปา) – The world of the "untroubled" devas, whose company those of lower realms wish for. The height of this world is 20,971,520 yojanas above the Earth (approximately the distance of Sun from Earth).

- Avṛha अवृह or Aviha अविह (Thai: อวิหา or อวรรหา) – The world of the "not falling" devas, perhaps the most common destination for reborn Anāgāmins. Many achieve arhatship directly in this world, but some pass away and are reborn in sequentially higher worlds of the Pure Abodes until they are at last reborn in the Akaniṣṭha world. These are called in Pāli uddhaṃsotas, "those whose stream goes upward". The duration of life in Avṛha is 1,000 kalpas (Vibhajyavāda tradition). The height of this world is 10,485,760 yojanas above the Earth (approximately the distance of Mars from Earth).

Bṛhatphala worlds बृहत्फल

The mental state of the devas of the Bṛhatphala worlds (Chn: 四禅九天/四禪九天; Jpn: 四禅九天; Thai: เวหปฺปผลา) corresponds to the fourth dhyāna, and is characterized by equanimity (upekṣā). The Bṛhatphala worlds form the upper limit to the destruction of the universe by wind at the end of a mahākalpa (see Temporal cosmology below), that is, they are spared such destruction.

- Asaññasatta असञ्ञसत्त (Sanskrit: Asaṃjñasattva असंज्ञसत्त्व; Thai: อสัญฺญสัตฺตา or อสํชญสตฺวา) (Vibhajyavāda tradition only) – "Unconscious beings", devas who have attained a high dhyāna (similar to that of the Formless Realm), and, wishing to avoid the perils of perception, have achieved a state of non-perception in which they endure for a time. After a while, however, perception arises again and they fall into a lower state.

- Bṛhatphala बृहत्फल or Vehapphala वेहप्फल (Tib: 'bras bu che; Thai: เวหัปปผลา or พรฺหตฺผลา) – Devas "having great fruit". Their lifespan is 500 mahākalpas. (Vibhajyavāda tradition). Some Anāgāmins are reborn here. The height of this world is 5,242,880 yojanas above the Earth.(approximately the distance of Venus from Earth)

- Puṇyaprasava पुण्यप्रसव (Sarvāstivāda tradition only; Tib: bsod nams skyes; Thai: ปณฺยปรัสวา) – The world of the devas who are the "offspring of merit". The height of this world is 2,621,440 yojanas above the Earth.

- Anabhraka अनभ्रक (Sarvāstivāda tradition only; Tib: sprin med; Thai อนภร๎กา) – The world of the "cloudless" devas. The height of this world is 1,310,720 yojanas above the Earth.

Śubhakṛtsna worlds

The mental state of the devas of the Śubhakṛtsna worlds (Chn/Jpn: 三禅三天; Devanagari: शुभकृत्स्न; Thai: ศุภกฤตฺสนาภูมิ) corresponds to the third dhyāna, and is characterized by a quiet joy (sukha). These devas have bodies that radiate a steady light. The Śubhakṛtsna worlds form the upper limit to the destruction of the universe by water at the end of a mahākalpa (see Temporal cosmology below), that is, the flood of water does not rise high enough to reach them.

- Śubhakṛtsna शुभकृत्स्न or Subhakiṇṇa / Subhakiṇha सुभकिण्ण/सुभकिण्ह (Tib: dge rgyas; Thai: สุภกิณหา or ศุภกฤตฺสนา) – The world of devas of "total beauty". Their lifespan is 64 mahākalpas (some sources: 4 mahākalpas) according to the Vibhajyavāda tradition. 64 mahākalpas is the interval between destructions of the universe by wind, including the Śubhakṛtsna worlds. The height of this world is 655,360 yojanas above the Earth.

- Apramāṇaśubha अप्रमाणशुभ or Appamāṇasubha अप्पमाणसुभ (Tib: tshad med dge; Thai: อัปปมาณสุภา or อัปรมาณศุภา) – The world of devas of "limitless beauty". Their lifespan is 32 mahākalpas (Vibhajyavāda tradition). They possess "faith, virtue, learning, munificence and wisdom". The height of this world is 327,680 yojanas above the Earth.

- Parīttaśubha परीत्तशुभ or Parittasubha परित्तसुभ (Tib: dge chung; Thai: ปริตฺตสุภา or ปรีตฺตศุภา) – The world of devas of "limited beauty". Their lifespan is 16 mahākalpas. The height of this world is 163,840 yojanas above the Earth.

Ābhāsvara worlds

The mental state of the devas of the Ābhāsvara आभास्वर worlds (Chn/Jpn: 二禅三天; Thai: อาภัสสราภูมิ/อาภาสวราธาตุ) corresponds to the second dhyāna, and is characterized by delight (prīti) as well as joy (sukha); the Ābhāsvara devas are said to shout aloud in their joy, crying aho sukham! ("Oh joy!"). These devas have bodies that emit flashing rays of light like lightning. They are said to have similar bodies (to each other) but diverse perceptions.

The Ābhāsvara worlds form the upper limit to the destruction of the universe by fire at the end of a mahākalpa (see Temporal cosmology below), that is, the column of fire does not rise high enough to reach them. After the destruction of the world, at the beginning of the vivartakalpa, the worlds are first populated by beings reborn from the Ābhāsvara worlds.

- Ābhāsvara आभास्वर or Ābhassara' आभस्सर (Tib: 'od gsal; Thai: อาภัสสรา or อาภาสวรา) – The world of devas "possessing splendor". The lifespan of the Ābhāsvara devas is 8 mahākalpas (others: 2 mahākalpas). Eight mahākalpas is the interval between destructions of the universe by water, which includes the Ābhāsvara worlds. The height of this world is 81,920 yojanas above the Earth.

- Apramāṇābha अप्रमाणाभ or Appamāṇābha अप्पमाणाभ (Tib: tshad med 'od; Thai: อัปปมาณาภา or อัปรมาณาภา) – The world of devas of "limitless light", a concept on which they meditate. Their lifespan is 4 mahākalpas. The height of this world is 40,960 yojanas above the Earth.

- Parīttābha परीत्ताभ or Parittābha परित्ताभ (Tib: 'od chung; Thai: ปริตฺตาภา or ปรีตตาภา) – The world of devas of "limited light". Their lifespan is 2 mahākalpas. The height of this world is 20,480 yojanas above the Earth.

Brahmā worlds

The mental state of the devas of the Brahmā worlds (Chn/Jpn: 初禅三天; Thai: พรหมภูมิ) corresponds to the first dhyāna, and is characterized by observation (vitarka) and reflection (vicāra) as well as delight (prīti) and joy (sukha). The Brahmā worlds, together with the other lower worlds of the universe, are destroyed by fire at the end of a mahākalpa (see Temporal cosmology below).

- Mahābrahmā महाब्रह्मा (Tib: tshangs pa chen po; Chn/Jpn: 大梵天 Daibonten; Thai: มหาพรหฺมฺา) – the world of "Great Brahmā", believed by many to be the creator of the world, and having as his titles "Brahmā, Great Brahmā, the Conqueror, the Unconquered, the All-Seeing, All-Powerful, the Lord, the Maker and Creator, the Ruler, Appointer and Orderer, Father of All That Have Been and Shall Be." According to the Brahmajāla Sutta (DN.1), a Mahābrahmā is a being from the Ābhāsvara worlds who falls into a lower world through exhaustion of his merits and is reborn alone in the Brahma-world; forgetting his former existence, he imagines himself to have come into existence without cause. Note that even such a high-ranking deity has no intrinsic knowledge of the worlds above his own. Mahābrahmā is 1 1⁄2 yojanas tall. His lifespan variously said to be 1 kalpa (Vibhajyavāda tradition) or 1 1⁄2 kalpas long (Sarvāstivāda tradition), although it would seem that it could be no longer than 3⁄4 of a mahākalpa, i.e., all of the mahākalpa except for the Saṃvartasthāyikalpa, because that is the total length of time between the rebuilding of the lower world and its destruction. It is unclear what period of time "kalpa" refers to in this case. The height of this world is 10,240 yojanas above the Earth.

- Brahmapurohita ब्रह्मपुरोहित (Tib: tshangs 'khor; Thai: พรหฺมปุโรหิตา) – the "Ministers of Brahmā" are beings, also originally from the Ābhāsvara worlds, that are born as companions to Mahābrahmā after he has spent some time alone. Since they arise subsequent to his thought of a desire for companions, he believes himself to be their creator, and they likewise believe him to be their creator and lord. They are 1 yojana in height and their lifespan is variously said to be 1⁄2 of a kalpa (Vibhajyavāda tradition) or a whole kalpa (Sarvāstivāda tradition). If they are later reborn in a lower world, and come to recall some part of their last existence, they teach the doctrine of Brahmā as creator as a revealed truth. The height of this world is 5,120 yojanas above the Earth.

- Brahmapāriṣadya ब्रह्मपारिषद्य or Brahmapārisajja ब्रह्मपारिसज्ज (Tib: tshangs ris; Thai: พรหฺมปริสัชชา or พรหฺมปาริษัตยา) – the "Councilors of Brahmā" or the devas "belonging to the assembly of Brahmā". They are also called Brahmakāyika, but this name can be used for any of the inhabitants of the Brahma-worlds. They are half a yojana in height and their lifespan is variously said to be 1⁄3 of a kalpa (Vibhajyavāda tradition) or 1⁄2 of a kalpa (Sarvāstivāda tradition). The height of this world is 2,560 yojanas above the Earth.

Desire Realm (Kāmadhātu कामधातु)

The beings born in the Kāmadhātu कामधातु (Pāli: Kāmaloka कामलोक; Tib: 'dod pa'i khams; Chn/Jpn: 欲界 Yoku-kai; Thai: กามภูมิ) differ in degree of happiness, but they are all, other than Anagamis, Arhats and Buddhas, under the domination of Māra and are bound by sensual desire, which causes them suffering.

Heavens

The following four worlds are bounded planes, each 80,000 yojanas square, which float in the air above the top of Mount Sumeru. Although all of the worlds inhabited by devas (that is, all the worlds down to the Cāturmahārājikakāyika world and sometimes including the Asuras) are sometimes called "heavens", in the western sense of the word the term best applies to the four worlds listed below:

- Parinirmita-vaśavartin परिनिर्मितवशवर्ती or Paranimmita-vasavatti परनिम्मितवसवत्ति (Tib: gzhan 'phrul dbang byed; Chn/Jpn: 他化自在天 Takejizai-ten; Burmese: ပရနိမ္မိတဝသဝတ္တီ; Thai: ปรนิมมิตวสวัตฺติ or ปริเนรมิตวศวรติน) – The heaven of devas "with power over (others') creations". These devas do not create pleasing forms that they desire for themselves, but their desires are fulfilled by the acts of other devas who wish for their favor. The ruler of this world is called Vaśavartin (Pāli: Vasavatti), who has longer life, greater beauty, more power and happiness and more delightful sense-objects than the other devas of his world. This world is also the home of the devaputra (being of divine race) called Māra, who endeavors to keep all beings of the Kāmadhātu in the grip of sensual pleasures. Māra is also sometimes called Vaśavartin, but in general these two dwellers of this world are kept distinct. The beings of this world are 4,500 feet (1,400 m) tall and live for 9,216,000,000 years (Sarvāstivāda tradition). The height of this world is 1,280 yojanas above the Earth.

- Nirmāṇarati निर्माणरति or Nimmānaratī निम्माणरती (Tib: phrul dga; Chn: 化乐天/化樂天; Jpn: 化楽天 Keraku-ten; Burmese: နိမ္မာနရတိ; Thai: นิมมานรติ or นิรมาณรติ)– The world of devas "delighting in their creations". The devas of this world are capable of making any appearance to please themselves. The lord of this world is called Sunirmita (Pāli: Sunimmita); his wife is the rebirth of Visākhā, formerly the chief of the upāsikās (female lay devotees) of the Buddha. The beings of this world are 3,750 feet (1,140 m) tall and live for 2,304,000,000 years (Sarvāstivāda tradition). The height of this world is 640 yojanas above the Earth.

- Tuṣita तुषित or Tusita तुसित (Tib: dga' ldan; Chn/Jpn: 兜率天 Tosotsu-ten; Burmese: တုသိတာ; Thai: ดุสิต, ตุสิตา or ตุษิตา ) – The world of the "joyful" devas. This world is best known for being the world in which a Bodhisattva lives before being reborn in the world of humans. Until a few thousand years ago, the Bodhisattva of this world was Śvetaketu (Pāli: Setaketu), who was reborn as Siddhārtha, who would become the Buddha Śākyamuni; since then the Bodhisattva has been Nātha (or Nāthadeva) who will be reborn as Ajita and will become the Buddha Maitreya (Pāli Metteyya). While this Bodhisattva is the foremost of the dwellers in Tuṣita, the ruler of this world is another deva called Santuṣita (Pāli: Santusita). The beings of this world are 3,000 feet (910 m) tall and live for 576,000,000 years (Sarvāstivāda tradition). The height of this world is 320 yojanas above the Earth.

- Yāma याम (Tib: 'thab bral; Chn/Jpn: 夜摩天 Yama-ten; Burmese: ယာမာ; Thai: ยามา) – Sometimes called the "heaven without fighting", because it is the lowest of the heavens to be physically separated from the tumults of the earthly world. These devas live in the air, free of all difficulties. Its ruler is the deva Suyāma; according to some, his wife is the rebirth of Sirimā, a courtesan of Rājagṛha in the Buddha's time who was generous to the monks. The beings of this world are 2,250 feet (690 m) tall and live for 144,000,000 years (Sarvāstivāda tradition). The height of this world is 160 yojanas above the Earth.

Worlds of Sumeru

The world-mountain of Sumeru सुमेरु (Sineru सिनेरु; Thai: เขาพระสุเมรุ, สิเนรุบรรพต) is an immense, strangely shaped peak which arises in the center of the world, and around which the Sun and Moon revolve. Its base rests in a vast ocean, and it is surrounded by several rings of lesser mountain ranges and oceans. The three worlds listed below are all located on, or around, Sumeru: the Trāyastriṃśa devas live on its peak, the Cāturmahārājikakāyika devas live on its slopes, and the Asuras live in the ocean at its base. Sumeru and its surrounding oceans and mountains are the home not just of these deities, but also vast assemblies of beings of popular mythology who only rarely intrude on the human world.

- Trāyastriṃśa त्रायस्त्रिंश or Tāvatiṃsa तावतिंस (Tib: sum cu rtsa gsum pa; Chn/Jpn: 忉利天/三十三天 Tōri-ten; တာဝတိံသာ; Thai: ดาวดึงส์, ไตรตรึงศ์, ตาวติํสา or ตฺรายสฺตฺริศ) – The world "of the Thirty-three (devas)" is a wide flat space on the top of Mount Sumeru, filled with the gardens and palaces of the devas. Its ruler is Śakro devānām indra, शक्रो देवानामिन्द्रः ”Śakra, lord of the devas". Besides the eponymous Thirty-three devas, many other devas and supernatural beings dwell here, including the attendants of the devas and many heavenly courtesans (es or nymphs). The beings of this world are 1,500 feet (460 m) tall and live for 36,000,000 years (Sarvāstivāda tradition) or 3/4 of a yojana tall and live for 30,000,000 years (Vibhajyavāda tradition). The height of this world is 80 yojanas above the Earth.

- Cāturmahārājikakāyika चातुर्महाराजिककायिक or Cātummahārājika चातुम्महाराजिक (Tib: rgyal chen bzhi; Chn:四天王天; Jpn: 四大王衆天 Shidaiōshu-ten; စတုမဟာရာဇ်; Thai: จาตุมฺมหาราชิกา or จาตุรมหาราชิกกายิกา) – The world "of the Four Great Kings" is found on the lower slopes of Mount Sumeru, though some of its inhabitants live in the air around the mountain. Its rulers are the four Great Kings of the name, Virūḍhaka विरूढकः, Dhṛtarāṣṭra धृतराष्ट्रः, Virūpākṣa विरूपाक्षः, and their leader Vaiśravaṇa वैश्रवणः. The devas who guide the Sun and Moon are also considered part of this world, as are the retinues of the four kings, composed of Kumbhāṇḍas कुम्भाण्ड (dwarfs), Gandharvas गन्धर्व (fairies), Nāgas नाग (dragons) and Yakṣas यक्ष (goblins). The beings of this world are 750 feet (230 m) tall and live for 9,000,000 years (Sarvāstivāda tradition) or 90,000 years (Vibhajyavāda tradition). The height of this world is from sea level up to 40 yojanas above the Earth.

- Asura असुर (Tib: lha ma yin; Chn/Jpn: 阿修羅 Ashura; Burmese: အသူရာ; Thai: อสุรกาย) – The world of the Asuras is the space at the foot of Mount Sumeru, much of which is a deep ocean. It is not the Asuras' original home, but the place they found themselves after they were hurled, drunken, from Trāyastriṃśa where they had formerly lived. The Asuras are always fighting to regain their lost kingdom on the top of Mount Sumeru, but are unable to break the guard of the Four Great Kings. The Asuras are divided into many groups, and have no single ruler, but among their leaders are Vemacitrin वेमचित्री (Pāli: Vepacitti वेपचित्ती) and Rāhu.

Earthly realms

- Manuṣyaloka मनुष्यलोक (Tib: mi; Chn/Jpn: 人 nin; Burmese: မနုဿဘုံ;

Thai: มนุสสภูมิ or มนุษยโลก) – This is the world of humans and

human-like beings who live on the surface of the earth. The

mountain-rings that engird Sumeru are surrounded by a vast ocean, which

fills most of the world. The ocean is in turn surrounded by a circular

mountain wall called Cakravāḍa चक्रवाड (Pāli: Cakkavāḷa चक्कवाळ ;

Thai: จักรวาล or จกฺกวาฬ) which marks the horizontal limit of the

world. In this ocean there are four continents which are, relatively

speaking, small islands in it. Because of the immenseness of the ocean,

they cannot be reached from each other by ordinary sailing vessels,

although in the past, when the cakravartin kings ruled, communication

between the continents was possible by means of the treasure called the cakraratna (Pāli cakkaratana’’’),

which a cakravartin king and his retinue could use to fly through the

air between the continents. The four continents are:

- Jambudvīpa जम्वुद्वीप or Jambudīpa जम्बुदीप (Chn/Jpn: 閻浮提 Enbudai; Burmese; ဇမ္ဗုဒီပ; Thai: ชมพูทวีป) is located in the south and is the dwelling of ordinary human beings. It is said to be shaped "like a cart", or rather a blunt-nosed triangle with the point facing south. (This description probably echoes the shape of the coastline of southern India.) It is 10,000 yojanas in extent (Vibhajyavāda tradition) or has a perimeter of 6,000 yojanas (Sarvāstivāda tradition) to which can be added the southern coast of only 3.5 yojanas' length. The continent takes its name from a giant Jambu tree (Syzygium cumini), 100 yojanas tall, which grows in the middle of the continent. Every continent has one of these giant trees. All Buddhas appear in Jambudvīpa. The people here are five to six feet tall and their length of life varies between 10 and about 10140 years (Asankya Aayu).

- Pūrvavideha पूर्वविदेह or Pubbavideha पुब्बविदेह (Burmese: ပုဗ္ဗဝိဒေဟ; Thai: ปุพพวิเทหทีป or บูรพวิเทหทวีป) is located in the east, and is shaped like a semicircle with the flat side pointing westward (i.e., towards Sumeru). It is 7,000 yojanas in extent (Vibhajyavāda tradition) or has a perimeter of 6,350 yojanas of which the flat side is 2,000 yojanas long (Sarvāstivāda tradition). Its tree is the acacia, or Albizia lebbeck (Sukhōthai tradition). The people here are about 12 feet (3.7 m) tall and they live for 700 years. Their main work is trading and buying materials.

- Aparagodānīya अपरगोदानीय or Aparagoyāna अपरगोयान (Burnese: အပရဂေါယာန; Thai: อปรโคยานทวีป or อปรโคทานียทวีป) is located in the west, and is shaped like a circle with a circumference of about 7,500 yojanas (Sarvāstivāda tradition). The tree of this continent is a giant Kadamba tree (Anthocephalus chinensis). The human inhabitants of this continent do not live in houses but sleep on the ground. Their main transportation is Bullock cart. They are about 24 feet (7.3 m) tall and they live for 500 years.

- Uttarakuru उत्तरकुरु (Burmese; ဥတ္တရကုရု; Thai: อุตรกุรุทวีป) is located in the north, and is shaped like a square. It has a perimeter of 8,000 yojanas, being 2,000 yojanas on each side. This continent's tree is called a kalpavṛkṣa कल्पवृक्ष (Pāli: kapparukkha कप्परुक्ख) or kalpa-tree, because it lasts for the entire kalpa. The inhabitants of Uttarakuru have cities built in the air. They are said to be extraordinarily wealthy, not needing to labor for a living – as their food grows by itself – and having no private property. They are about 48 feet (15 m) tall and live for 1,000 years, and they are under the protection of Vaiśravaṇa.

- Tiryagyoni-loka तिर्यग्योनिलोक or Tiracchāna-yoni तिरच्छानयोनि (Tib: dud 'gro; Chn/Jpn: 畜生 chikushō; Burmese: တိရစ္ဆာန်ဘုံ; Thai: เดรัจฉานภูมิ or ติรยคฺโยนิโลก) – This world comprises all members of the animal kingdom that are capable of feeling suffering, regardless of size.

- Pretaloka प्रेतलोक or Petaloka पेतलोक (Tib: yi dwags; Burmese: ပြိတ္တာ; Thai: เปรตภูมิ or เปตฺตโลก) – The pretas, or "hungry ghosts", are mostly dwellers on earth, though due to their mental state they perceive it very differently from humans. They live for the most part in deserts and wastelands.

Hells (Narakas)

Naraka नरक or Niraya निरय (Tib: dmyal ba; Burmese; ငရဲ; Thai: นรก) is the name given to one of the worlds of greatest suffering, usually translated into English as "hell" or "purgatory". As with the other realms, a being is born into one of these worlds as a result of his karma, and resides there for a finite length of time until his karma has achieved its full result, after which he will be reborn in one of the higher worlds as the result of an earlier karma that had not yet ripened. The mentality of a being in the hells corresponds to states of extreme fear and helpless anguish in humans.

Physically, Naraka is thought of as a series of layers extending below Jambudvīpa into the earth. There are several schemes for counting these Narakas and enumerating their torments. One of the more common is that of the Eight Cold Narakas and Eight Hot Narakas.

Cold Narakas

- Arbuda अर्बुद – the "blister" Naraka

- Nirarbuda निरर्बुद – the "burst blister" Naraka

- Ataṭa अतट – the Naraka of shivering

- Hahava हहव – the Naraka of lamentation

- Huhuva हुहुव – the Naraka of chattering teeth

- Utpala उत्पल – the Naraka of skin becoming blue as a blue lotus

- Padma पद्म – the Naraka of cracking skin

- Mahāpadma महापद्म – the Naraka of total frozen bodies falling apart

Each lifetime in these Narakas is twenty times the length of the one before it.

Hot Narakas

- Sañjīva सञ्जीव (Burmese: သိဉ္ဇိုး ငရဲ; Thai: สัญชีวมหานรก) – the "reviving" Naraka. Life in this Naraka is 162×1010 years long.

- Kālasūtra कालसूत्र (Burmese: ကာဠသုတ် ငရဲ; Thai: กาฬสุตตมหานรก/กาลสูตร) – the "black thread" Naraka. Life in this Naraka is 1296×1010 years long.

- Saṃghāta संघात (Burmese: သင်္ဃာတ ငရဲ; Thai: สังฆาฏมหานรก or สํฆาต) – the "crushing" Naraka. Life in this Naraka is 10,368×1010 years long.

- Raurava/Rīrava रौरव/रीरव (Burmese: ရောရုဝ ငရဲ; Thai: โรรุวมหานรก) – the "screaming" Naraka. Life in this Naraka is 82,944×1010 years long.

- Mahāraurava/Mahārīrava महारौरव/महारीरव (Burmese: မဟာရောရုဝ ငရဲ; Thai: มหาโรรุวมหานรก) – the "great screaming" Naraka. Life in this Naraka is 663,552×1010 years long.

- Tāpana/Tapana तापन/तपन (Burmese: တာပန ငရဲ; Thai: ตาปนมหานรก) – the "heating" Naraka. Life in this Naraka is 5,308,416×1010 years long.

- Mahātāpana महातापन (Burmese: မဟာတာပန ငရဲ; Thai: มหาตาปนมหานรก) – the "great heating" Naraka. Life in this Naraka is 42,467,328×1010 years long.

- Avīci अवीचि (Burmese: အဝီစိ ငရဲ;Thai: อเวจีมหานรก/อวิจี) – the "uninterrupted" Naraka. Life in this Naraka is 339,738,624×1010 years long.

Each lifetime in these Narakas is eight times the length of the one before it.

The foundations of the earth

All of the structures of the earth, Sumeru and the rest, extend downward to a depth of 80,000 yojanas below sea level – the same as the height of Sumeru above sea level. Below this is a layer of "golden earth", a substance compact and firm enough to support the weight of Sumeru. It is 320,000 yojanas in depth and so extends to 400,000 yojanas below sea level. The layer of golden earth in turn rests upon a layer of water, which is 8,000,000 yojanas in depth, going down to 8,400,000 yojanas below sea level. Below the layer of water is a "circle of wind", which is 16,000,000 yojanas in depth and also much broader in extent, supporting 1,000 different worlds upon it. Yojanas are equivalent to about 13 km (8 mi).

Sahasra cosmology

Sahasra means "one thousand". All of the planes, from the plane of neither perception nor non-perception (nevasanna-asanna-ayatana) down to the Avīci – the "without interval") niraya – constitutes the single world-system, cakkavāḷa (intimating something circular, a "wheel", but the etymology is uncertain), described above. In modern parlance it would be called a 'universe', or 'solar system'.

A collection of one thousand solar systems are called a "thousandfold minor world-system" (culanika lokadhatu). Or small chiliocosm.

A collection of 1,000 times 1,000 world-systems (one thousand squared) is a "thousandfold to the second power middling world-system" (dvisahassi majjhima lokadhatu). Or medium dichiliocosm.

The largest grouping, which consists of one thousand cubed world-systems, is called the "tisahassi mahasassi lokadhatu". Or great trichiliocosm.

The Tathagata, if he so wished, could effect his voice throughout a great trichiliocosm. He does so by suffusing the trichiliocosm with his radiance, at which point the inhabitants of those world-system will perceive this light, and then proceeds to extend his voice throughout that realm.

Maha Kalpa

The word kalpa, means 'moment'. A maha kalpa consists of four moments (kalpa), the first of which is creation. The creation moment consists of the creation of the "receptacle", and the descent of beings from higher realms into more coarse forms of existence. During the rest of the creation moment, the world is populated. Human beings who exist at this point have no limit on their lifespan. The second moment is the duration moment, the start of this moment is signified by the first sentient being to enter hell (niraya), the hells and nirayas not existing or being empty prior to this moment. The duration moment consists of twenty "intermediate" moments (antarakappas), which unfold in a drama of the human lifespan descending from 80,000 years to 10, and then back up to 80,000 again. The interval between 2 of these "intermediate" moments is the "seven day purge", in which a variety of humans will kill each other (not knowing or recognizing each other), some humans will go into hiding. At the end of this purge, they will emerge from hiding and repopulate the world. After this purge, the lifespan will increase to 80,000, reach its peak and descend, at which point the purge will happen again.

Within the duration 'moment', this purge and repeat cycle seems to happen around 18 times, the first "intermediate" moment consisting only of the descent from 80,000 – the second intermediate moment consisting of a rise and descent, and the last consisting only of an ascent.

After the duration 'moment' is the dissolution moment, the hells will gradually be emptied, as well as all coarser forms of existence. The beings will flock to the form realms (rupa dhatu), a destruction of fire occurs, sparing everything from the realms of the 'radiant' gods and above (abha deva).

After 7 of these destructions by 'fire', a destruction by water occurs, and everything from the realms of the 'pleasant' gods and above is spared (subha deva).

After 64 of these destructions by fire and water, that is – 56 destructions by fire, and 7 by water – a destruction by wind occurs, this eliminates everything below the realms of the 'fruitful' devas (vehapphala devas, literally of "great fruit"). The pure abodes (suddhavasa, meaning something like pure, unmixed, similar to the connotation of "pure bred German shepherd"), are never destroyed. Although without the appearance of a Buddha, these realms may remain empty for a long time. The inhabitants of these realms have exceedingly long life spans.

The formless realms are never destroyed because they do not consist of form (rupa). The reason the world is destroyed by fire, water and wind, and not earth is because earth is the 'receptacle'.

After the dissolution moment, this particular world system remains dissolved for a long time, this is called the 'empty' moment, but the more accurate term would be "the state of being dissolved". The beings that inhabited this realm formerly will migrate to other world systems, and perhaps return if their journeys lead here again.

Temporal cosmology

Buddhist temporal cosmology describes how the universe comes into being and is dissolved. Like other Indian cosmologies, it assumes an infinite span of time and is cyclical. This does not mean that the same events occur in identical form with each cycle, but merely that, as with the cycles of day and night or summer and winter, certain natural events occur over and over to give some structure to time.

The basic unit of time measurement is the mahākalpa or "Great Eon" (Chn/Jpn: 大劫 daigō; Thai: มหากัปป์ or มหากัลป์; Devanagari: महाकल्प / महाकप्प). The length of this time in human years is never defined exactly, but it is meant to be very long, to be measured in billions of years if not longer.

A mahākalpa is divided into four kalpas or "eons" (Chn/Jpn: 劫 kō; Thai: กัป; अन्तरकल्प), each distinguished from the others by the stage of evolution of the universe during that kalpa. The four kalpas are:

- Vivartakalpa विवर्तकल्प "Eon of evolution" – during this kalpa the universe comes into existence.

- Vivartasthāyikalpa विवर्तस्थायिकल्प "Eon of evolution-duration" – during this kalpa the universe remains in existence in a steady state.

- Saṃvartakalpa संवर्तकल्प "Eon of dissolution" – during this kalpa the universe dissolves.

- Saṃvartasthāyikalpa संवर्तस्थायिकल्प "Eon of dissolution-duration" – during this kalpa the universe remains in a state of emptiness.

Each one of these kalpas is divided into twenty antarakalpas अन्तरकल्प (Pāli: antarakappa अन्तरकप्प; Chn/Jpn: 中劫, "inside eons"; Thai: อันตรกัป) each of about the same length. For the Saṃvartasthāyikalpa this division is merely nominal, as nothing changes from one antarakalpa to the next; but for the other three kalpas it marks an interior cycle within the kalpa.

Vivartakalpa

The Vivartakalpa begins with the arising of the primordial wind, which begins the process of building up the structures of the universe that had been destroyed at the end of the last mahākalpa. As the extent of the destruction can vary, the nature of this evolution can vary as well, but it always takes the form of beings from a higher world being born into a lower world. The example of a Mahābrahmā being the rebirth of a deceased Ābhāsvara deva is just one instance of this, which continues throughout the Vivartakalpa until all the worlds are filled from the Brahmaloka down to Naraka. During the Vivartakalpa the first humans appear; they are not like present-day humans, but are beings shining in their own light, capable of moving through the air without mechanical aid, living for a very long time, and not requiring sustenance; they are more like a type of lower deity than present-day humans are.

Over time, they acquire a taste for physical nutriment, and as they consume it, their bodies become heavier and more like human bodies; they lose their ability to shine, and begin to acquire differences in their appearance, and their length of life decreases. They differentiate into two sexes and begin to become sexually active. Then greed, theft and violence arise among them, and they establish social distinctions and government and elect a king to rule them, called Mahāsammata। महासम्मत, "the great appointed one". Some of them begin to hunt and eat the flesh of animals, which have by now come into existence.

Vivartasthāyikalpa

First antarakalpa

The Vivartasthāyikalpa begins when the first being is born into Naraka, thus filling the entire universe with beings. During the first antarakalpa of this eon, the duration of human lives declines from a vast but unspecified number of years (but at least several tens of thousands of years) toward the modern lifespan of less than 100 years. At the beginning of the antarakalpa, people are still generally happy. They live under the rule of a universal monarch or "wheel-turning king" (Sanskrit: cakravartin चक्रवर्ति; Jpn: 転輪聖王 Tenrin Jō-ō; Thai: พระเจ้าจักรพรรดิ), who conquer. The Mahāsudassana-sutta (DN.17) tells of the life of a cakravartin king, Mahāsudassana (Sanskrit: Mahāsudarśana) who lived for 336,000 years. The Cakkavatti-sīhanāda-sutta (DN.26) tells of a later dynasty of cakravartins, Daḷhanemi (Sanskrit: Dṛḍhanemi) and five of his descendants, who had a lifespan of over 80,000 years. The seventh of this line of cakravartins broke with the traditions of his forefathers, refusing to abdicate his position at a certain age, pass the throne on to his son, and enter the life of a śramaṇa श्रमण. As a result of his subsequent misrule, poverty increased; as a result of poverty, theft began; as a result of theft, capital punishment was instituted; and as a result of this contempt for life, murders and other crimes became rampant.

The human lifespan now quickly decreased from 80,000 to 100 years, apparently decreasing by about half with each generation (this is perhaps not to be taken literally), while with each generation other crimes and evils increased: lying, greed, hatred, sexual misconduct, disrespect for elders. During this period, according to the Mahāpadāna-sutta (DN.14) three of the four Buddhas of this antarakalpa lived: Krakucchanda Buddha क्रकुच्छन्दः (Pāli: Kakusandha ककुन्ध), at the time when the lifespan was 40,000 years; Kanakamuni कनकमुनिः Buddha (Pāli: Konāgamana कोनागमन) when the lifespan was 30,000 years; and Kāśyapa काश्यपः Buddha (Pāli: Kassapa कस्सप) when the lifespan was 20,000 years.

Our present time is taken to be toward the end of the first antarakalpa of this Vivartasthāyikalpa, when the lifespan is less than 100 years, after the life of Śākyamuni शाक्यमुनिः Buddha (Pāli: Sakyamuni ), who lived to the age of 80.

The remainder of the antarakalpa is prophesied to be miserable: lifespans will continue to decrease, and all the evil tendencies of the past will reach their ultimate in destructiveness. People will live no longer than ten years, and will marry at five; foods will be poor and tasteless; no form of morality will be acknowledged. The most contemptuous and hateful people will become the rulers. Incest will be rampant. Hatred between people, even members of the same family, will grow until people think of each other as hunters do of their prey.

Eventually a great war will ensue, in which the most hostile and aggressive will arm themselves with swords in their hands and go out to kill each other. The less aggressive will hide in forests and other secret places while the war rages. This war marks the end of the first antarakalpa.

Second antarakalpa

At the end of the war, the survivors will emerge from their hiding places and repent their evil habits. As they begin to do good, their lifespan increases, and the health and welfare of the human race will also increase with it. After a long time, the descendants of those with a 10-year lifespan will live for 80,000 years, and at that time there will be a cakravartin king named Saṅkha शंख. During his reign, the current bodhisattva in the Tuṣita heaven will descend and be reborn under the name of Ajita अजित. He will enter the life of a śramaṇa and will gain perfect enlightenment as a Buddha; and he will then be known by the name of Maitreya (मैत्रेयः, Pāli: Metteyya मेत्तेय्य).

After Maitreya's time, the world will again worsen, and the lifespan will gradually decrease from 80,000 years to 10 years again, each antarakalpa being separated from the next by devastating war, with peaks of high civilization and morality in the middle. After the 19th antarakalpa, the lifespan will increase to 80,000 and then not decrease, because the Vivartasthāyikalpa will have come to an end.

Saṃvartakalpa

The Saṃvartakalpa begins when beings cease to be born in Naraka. This cessation of birth then proceeds in reverse order up the vertical cosmology, i.e., pretas then cease to be born, then animals, then humans, and so on up to the realms of the deities.

When these worlds as far as the Brahmaloka are devoid of inhabitants, a great fire consumes the entire physical structure of the world. It burns all the worlds below the Ābhāsvara worlds. When they are destroyed, the Saṃvartasthāyikalpa begins.

Saṃvartasthāyikalpa

There is nothing to say about the Saṃvartasthāyikalpa, since nothing happens in it below the Ābhāsvara worlds. It ends when the primordial wind begins to blow and build the structure of the worlds up again.

Other destructions

The destruction by fire is the normal type of destruction that occurs at the end of the Saṃvartakalpa. But every eighth mahākalpa, after seven destructions by fire, there is a destruction by water. This is more devastating, as it eliminates not just the Brahma worlds but also the Ābhāsvara worlds.

Every sixty-fourth mahākalpa, after fifty six destructions by fire and seven destructions by water, there is a destruction by wind. This is the most devastating of all, as it also destroys the Śubhakṛtsna worlds. The higher worlds are never destroyed.