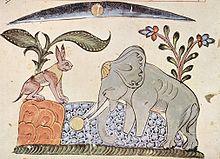

Personification occurs when a thing or abstraction is represented as a person, in literature or art, as an anthropomorphic metaphor. The type of personification discussed here excludes passing literary effects such as "Shadows hold their breath", and covers cases where a personification appears as a character in literature, or a human figure in art. The technical term for this, since ancient Greece, is prosopopoeia. In the arts many things are commonly personified. These include numerous types of places, especially cities, countries and the four continents, elements of the natural world such as the months or Four Seasons, Four Elements, Four Winds, Five Senses, and abstractions such as virtues, especially the four cardinal virtues and sins, the nine Muses, or death.

In many polytheistic early religions, deities had a strong element of personification, suggested by descriptions such as "god of". In ancient Greek religion, and the related Ancient Roman religion, this was perhaps especially strong, in particular among the minor deities. Many such deities, such as the tyches or tutelary deities for major cities, survived the arrival of Christianity, now as symbolic personifications stripped of religious significance. An exception was the winged goddess of Victory, Victoria/Nike, who developed into the visualization of the Christian angel.

Generally, personifications lack much in the way of narrative myths, although classical myth at least gave many of them parents among the major Olympian deities. The iconography of several personifications "maintained a remarkable degree of continuity from late antiquity until the 18th century". Female personifications tend to outnumber male ones, at least until modern national personifications, many of which are male.

Personifications are very common elements in allegory, and historians and theorists of personification complain that the two have been too often confused, or discussion of them dominated by allegory. Single images of personifications tend to be titled as an "allegory", arguably incorrectly. By the late 20th century personification seemed largely out of fashion, but the semi-personificatory superhero figures of many comic book series came in the 21st century to dominate popular cinema in a number of superhero film franchises.

According to Ernst Gombrich, "we tend to take it for granted rather than to ask questions about this extraordinary predominantly feminine population which greets us from the porches of cathedrals, crowds around our public monuments, marks our coins and our banknotes, and turns up in our cartoons and our posters; these females variously attired, of course, came to life on the medieval stage, they greeted the Prince on his entry into a city, they were invoked in innumerable speeches, they quarrelled or embraced in endless epics where they struggled for the soul of the hero or set the action going, and when the medieval versifier went out on one fine spring morning and lay down on a grassy bank, one of these ladies rarely failed to appear to him in his sleep and to explain her own nature to him in any number of lines".

History

Classical world

Personification as an artistic device is easier to discuss when belief in the personification as an actual spiritual being has died down; this seems to have happened in the ancient Graeco-Roman world, probably even before Christianization. In other cultures, especially Hinduism and Buddhism, many personification figures still retain their religious significance, which is why they are not covered here. For example Bharat Mata was devised as a Hindu goddess figure to act as a national personification by intellectuals in the Indian independence movement from the 1870s, but now has some actual Hindu temples.

Personification is found very widely in classical literature, art and drama, as well as the treatment of personifications as relatively minor deities, or the rather variable category of daemons. In classical Athens, every geographical division of the state for local government purposes had a personified deity which received some cultic attention, as well as Demos, a male personification for the governing assembly of free citizens, and Boule, a female one for the ruling council. These appear in art, but are often hard to identify if not labelled.

Personification in the Bible is mostly limited to passing phrases which can probably be regarded as literary flourishes, with the important and much-discussed exception of Wisdom in the Book of Proverbs, 1–9, where a female personification is treated at some length, and makes speeches. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse from the Book of Revelation can be regarded as personification figures, although the text does not specify what all personify.

According to James J. Paxson in his book on the subject "all personification figures prior to the sixth century A.D. were ... female"; but major rivers have male personifications much earlier, and are more often male, which often extends to "Water" in the Four Elements. The predominance of females is at least partly because Latin grammar gives nouns for abstractions the female gender.

Pairs of winged victories decorated the spandrels of Roman triumphal arches and similar spaces, and ancient Roman coinage was an especially rich source of images, many carrying their name, which was helpful for medieval and Renaissance antiquarians. Sets of tyches representing the major cities of the empire were used in the decorative arts. Most imaginable virtues and virtually every Roman province was personified on coins at some point, the provinces often initially seated dejected as "CAPTA" ("taken") after its conquest, and later standing, creating images such as Britannia that were often revived in the Renaissance or later.

Lucian (2nd century AD) records a detailed description of a lost painting by Apelles (4th century BC) called the Calumny of Apelles, which some Renaissance painters followed, most famously Botticelli. This included eight personifications of virtues and vices: Hope, Repentance, Perfidy, Calumny, Fraud, Rancour, Ignorance, Suspicion, as well as two other figures.

Platonism, which in some manifestations proposed systems involving numbers of spirits, was naturally conducive to personification and allegory, and is an influence on the uses of it from classical times through various revivals up to the Baroque period.

Literature

According to Andrew Escobedo, “literary personification mashalls inanimate things, such as passions, abstract ideas, and rivers, and makes them perform actions in the landscape of the narrative.” He dates “the rise and fall of its [personification’s] literary popularity” to "roughly, between the fifth and seventeenth centuries". Late antique philosophical books that made heavy use of personification and were specially influential in the Middle Ages included the Psychomachia of Prudentius (early 5th century), with an elaborate plot centred around battles between the virtues and vices, and The Consolation of Philosophy (c. 524) by Boethius, which takes the form of a dialogue between the author and "Lady Philosophy". Fortuna and the Wheel of Fortune were prominent and memorable in this, which helped to make the latter a favourite medieval trope. Both authors were Christians, and the origins in the pagan classical religions of the standard range of personifications had been left well behind.

A medieval creation was the Four Daughters of God, a shortened group of virtues consisting of: Truth, Righteousness or Justice, Mercy, and Peace. There were also the seven virtues, made up of the four classical cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, temperance and courage (or fortitude), these going back to Plato's Republic, with the three theological virtues of faith, hope and charity. The seven deadly sins were their counterparts.

The major works of Middle English literature had many personification characters, and often formed what are called "personification allegories" where the whole work is an allegory, largely driven by personifications. These include Piers Plowman by William Langland ( c. 1370–90), where most of the characters are clear personifications named as their qualities, and several works by Geoffrey Chaucer, such as The House of Fame (1379–80). However, Chaucer tends to take his personifications in the direction of being more complex characters and give them different names, as when he adapts part of the French Roman de la Rose (13th century). The English mystery plays and the later morality plays have many personifications as characters, alongside their biblical figures. Frau Minne, the spirit of courtly love in German medieval literature, had equivalents in other vernaculars.

In Italian literature Petrach's Triomphi, finished in 1374, is based around a procession of personifications carried on "cars", as was becoming fashionable in courtly festivities; it was illustrated by many different artists. Dante has several personification characters, but prefers using real persons to represent most sins and virtues.

In Elizabethan literature many of the characters in Edmund Spenser's enormous epic The Faerie Queene, though given different names, are effectively personifications, especially of virtues. The Pilgrim's Progress (1678) by John Bunyan was the last great personification allegory in English literature, from a strongly Protestant position (though see Thomson's Liberty below). A work like Shelley's The Triumph of Life, unfinished at his death in 1822, which to many earlier writers would have called for personifications to be included, avoids them, as does most Romantic literature, apart from that of William Blake. Leading critics had begun to complain about personification in the 18th century, and such "complaints only grow louder in the nineteenth century". According to Andrew Escobedo, there is now "an unstated scholarly consensus" that "personification is a kind of frozen or hollow version of literal characters", which "depletes the fiction".

Visual arts

Personifications, often in sets, frequently appear in medieval art, often illustrating or following literary works. The virtues and vices were probably the most common, and the virtues appear in many large sculptural programmes, for example the exteriors of Chartres Cathedral and Amiens Cathedral. In painting, both virtues and vices are personified along the lowest zone of the walls of the Scrovegni Chapel by Giotto (c. 1305), and are the main figures in Ambrogio Lorenzetti's Allegory of Good and Bad Government (1338–39) in the Palazzo Pubblico of Siena. In the Allegory of Bad Government Tyranny is enthroned, with Avarice, Pride, and Vainglory above him. Beside him on the magistrate's bench sit Cruelty, Deceit, Fraud, Fury, Division, and War, while Justice lies tightly bound below. The so-called Mantegna Tarocchi (c. 1465–75) are sets of fifty educational cards depicting personifications of social classes, the planets and heavenly bodies, and also social classes.

A new pair, once common on the portals of large churches, are Ecclesia and Synagoga. Death envisaged as a skeleton, often with a scythe and hour-glass, is a late medieval innovation, that became very common after the Black Death. However, it is rarely seen in funerary art "before the Counter-Reformation".

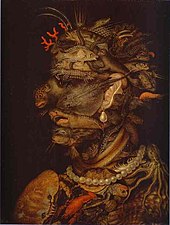

When not illustrating literary texts, or following a classical model as Botticelli does, personifications in art tend to be relatively static, and found together in sets, whether of statues decorating buildings or paintings, prints or media such as porcelain figures. Sometimes one or more virtues take on and invariably conquer vices. Other paintings by Botticelli are exceptions to such simple compositions, in particular his Primavera and The Birth of Venus, in both of which several figures form complex allegories. An unusually powerful single personification figure is depicted in Melencolia I (1514) an engraving by Albrecht Dürer. Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time (c. 1545) by Agnolo Bronzino has five personifications, apart from Venus and Cupid. In all these cases, the meaning of the work remains uncertain, despite intensive academic discussion, and even the identity of the figures continues to be argued over.

Theory

Around 300 BC, Demetrius of Phalerum is the first writer on rhetoric to describe prosopopoeia, which was already a well-established device in rhetoric and literature, from Homer onwards. Quintilian's lengthy Institutio Oratoria gives a comprehensive account, and a taxonomy of common personifications; no more comprehensive account was written until after the Renaissance. The main Renaissance humanists to deal with the subject at length were Erasmus in his De copia and Petrus Mosellanus in Tabulae de schematibus et tropis, who were copied by other writers throughout the 16th century.

From the late 16th century theoretical writers such as Karel van Mander in his Schilder-boeck (1604) began to treat personification in terms of the visual arts. At the same time the emblem book, describing and illustrating emblematic images that were largely personifications, became enormously popular, both with intellectuals and artists and craftsmen looking for motifs. The most famous of these was the Iconologia of Cesare Ripa, first published unillustrated in 1593, but from 1603 published in many different illustrated editions, using different artists. This set at least the identifying attributes carried by many personifications until the 19th century.

From the 20th century into the 21st, the past use of personification has received greatly increased critical attention, just as the artistic practice of it has greatly declined. Among a number of key works, The Allegory of Love: A Study in Medieval Tradition (1936), by C. S. Lewis was an exploration of courtly love in medieval and Renaissance literature.

Innovation

The classical repertoire of virtues, seasons, cities and so forth supplied the majority of subjects until the 19th century, but some new personifications became required. The 16th century saw the new personification of the Americas, and made the four continents an appealing new set, four figures being better suited to many contexts than three. The 18th-century discovery of Australia was not so quickly followed by an addition to the set, if only for reasons of geometry; Australia is not included in the continents at the corners of the Albert Memorial (1860s). This does have a set of three-figure groups representing agriculture, commerce, engineering and manufacturing, typical of the requirements for large public schemes of the period. A rather late example is the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House in New York City (1901–07), which has large groups for the four continents by the entrance, and 12 figures personifying seafaring nations from history high on the facade.

The invention of movable type printing saw Dame Imprimerie ("Lady Printing Press") introduced to the pageants of Lyons, a major printing centre, along with "Typosine", a new muse of printing. A large gilt-bronze statue by Evelyn Beatrice Longman, something of a specialist in "allegorical" statues, was commissioned by AT&T for the top of their New York headquarters. Since 1916 it has been titled at different times as the Genius of Telegraphy, Genius of Electricity, and since the 1930s Spirit of Communication. Shakespeare's spirit Ariel was adopted by the sculptor Eric Gill as a personification of broadcasting, and features in his sculptures on Broadcasting House in London (opened 1932).

National personifications

A number of national personifications stick to the old formulas, with a female in classical dress, carrying attributes suggesting power, wealth, or other virtues. Britannia is an example, derived from her figure on Roman coins, with a glance at the ancient goddess Roma; Germania and Helvetia are others.

Libertas, the Roman goddess of liberty, had been important under the Roman Republic, and was somewhat uncomfortably co-opted by the empire; it was not seen as an innate right, but as granted to some under Roman law. She had appeared on the coins of the assassins of Julius Caesar, defenders of the Roman republic. The medieval republics, mostly in Italy, greatly valued their liberty, and often use the word, but produce very few direct personifications. With the rise of nationalism and new states, many nationalist personifications included a strong element of liberty, perhaps culminating in the Statue of Liberty. The long poem Liberty by the Scottish James Thomson (1734), is a lengthy monologue spoken by the "Goddess of Liberty", describing her travels through the ancient world, and then English and British history, before the resolution of the Glorious Revolution of 1688 confirms her position there. Thomson also wrote the lyrics for Rule Britannia, and the two personifications were often combined as a personified "British Liberty", to whom a large monument was erected in the 1750s on his estate at Gibside by a Whig magnate.

But, sometimes alongside these formal figures, a new type of national personification has arisen, typified by John Bull (1712) and Uncle Sam (c. 1812). Both began as figures in more or less satirical literature, but achieved their prominence when taken in to political cartoons and other visual media. The post-revolutionary Marianne in France, official since 1792, is something of a mixture of styles, sometimes formal and classical, at others a woman of the streets of Paris personified. The Dutch Maiden is one of the earliest of these figures, and was mainly visual from the start, her efforts to repulse unwelcome Spanish advances shown in 16th-century popular prints.