European Parliament |

|---|

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ninth European Parliament | |||

European Parliament logo | |||

| Type | |||

| Type | A house of the European Union legislative procedure | ||

Term limits | none | ||

| History | |||

| Founded | 10 September 1952 | ||

| Preceded by | Common Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Community | ||

| Leadership | |||

Klaus Welle since 15 March 2009 | |

| Structure | |

|---|---|

| Seats | |

| |

Political groups | |

| Committees |

|---|

Length of term | 5 years |

|---|---|

| Salary | €8,932.86 (gross per month) |

| Elections | |

Chosen by member state, systems include:

| |

First election | 7–10 June 1979 |

Last election | 23–26 May 2019 |

Next election | 2024 |

| Motto | |

| United in diversity | |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Louise Weiss: Strasbourg, | |

| |

| Espace Léopold: Brussels, | |

| Website | |

| www | |

| Constitution | |

| Treaties of the European Union | |

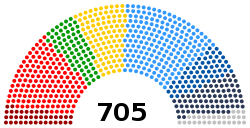

The European Parliament (EP) is one of three legislative branches of the European Union and one of its seven institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union, it adopts European legislation, commonly on the proposal of the European Commission. The Parliament is composed of 705 members (MEPs). It represents the second-largest democratic electorate in the world (after the Parliament of India) and the largest trans-national democratic electorate in the world (375 million eligible voters in 2009).

Since 1979, the Parliament has been directly elected every five years by the citizens of the European Union through universal suffrage. Voter turnout in parliamentary elections has decreased each time after 1979 until 2019, when voter turnout increased by 8 percentage points, and went above 50% for the first time since 1994. The voting age is 18 in all member states except for Malta and Austria, where it is 16, and Greece, where it is 17.

Although the European Parliament has legislative power, as does the Council, it does not formally possess the right of initiative – which is a prerogative of the European Commission – as most national parliaments of the member states do. The Parliament is the "first institution" of the European Union (mentioned first in its treaties and having ceremonial precedence over the other EU institutions), and shares equal legislative and budgetary powers with the Council (except on a few issues where the special legislative procedures apply). It likewise has equal control over the EU budget. Ultimately, the European Commission, which serves as the executive branch of the EU, is accountable to Parliament. In particular, Parliament can decide whether or not to approve the European Council's nominee for President of the Commission, and is further tasked with approving (or rejecting) the appointment of the Commission as a whole. It can subsequently coerce the current Commission to resign by adopting a motion of censure.

The President of the European Parliament (Parliament's speaker) is David Sassoli (PD), elected in July 2019. He presides over a multi-party chamber, the five largest groups being the European People's Party group (EPP), the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D), Renew Europe (previously ALDE), the Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens–EFA) and Identity and Democracy (ID). The last EU-wide elections were the 2019 elections.

The Parliament is headquartered in Strasbourg, France, and has its administrative offices in Luxembourg City. Plenary sessions take place in Strasbourg as well as in Brussels, Belgium, while the Parliament's committee meetings are held primarily in Brussels.

History

The Parliament, like the other institutions, was not designed in its current form when it first met on 10 September 1952. One of the oldest common institutions, it began as the Common Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). It was a consultative assembly of 78 appointed parliamentarians drawn from the national parliaments of member states, having no legislative powers. The change since its foundation was highlighted by Professor David Farrell of the University of Manchester: "For much of its life, the European Parliament could have been justly labelled a 'multi-lingual talking shop'."

Its development since its foundation shows how the European Union's structures have evolved without a clear ‘master plan’. Some, such as Tom Reid of the Washington Post, said of the union: "nobody would have deliberately designed a government as complex and as redundant as the EU". Even the Parliament's two seats, which have switched several times, are a result of various agreements or lack of agreements. Although most MEPs would prefer to be based just in Brussels, at John Major's 1992 Edinburgh summit, France engineered a treaty amendment to maintain Parliament's plenary seat permanently at Strasbourg.

Consultative assembly

The body was not mentioned in the original Schuman Declaration. It was assumed or hoped that difficulties with the British would be resolved to allow the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe to perform the task. A separate Assembly was introduced during negotiations on the Treaty as an institution which would counterbalance and monitor the executive while providing democratic legitimacy. The wording of the ECSC Treaty demonstrated the leaders' desire for more than a normal consultative assembly by using the term "representatives of the people" and allowed for direct election. Its early importance was highlighted when the Assembly was given the task of drawing up the draft treaty to establish a European Political Community. By this document, the Ad Hoc Assembly was established on 13 September 1952 with extra members, but after the failure of the negotiated and proposed European Defence Community (French parliament veto) the project was dropped.

Despite this, the European Economic Community and Euratom were established in 1958 by the Treaties of Rome. The Common Assembly was shared by all three communities (which had separate executives) and it renamed itself the European Parliamentary Assembly. The first meeting was held on 19 March 1958 having been set up in Luxembourg City, it elected Schuman as its president and on 13 May it rearranged itself to sit according to political ideology rather than nationality. This is seen as the birth of the modern European Parliament, with Parliament's 50 years celebrations being held in March 2008 rather than 2002.

The three communities merged their remaining organs as the European Communities in 1967, and the body's name was changed to the current "European Parliament" in 1962. In 1970 the Parliament was granted power over areas of the Communities' budget, which were expanded to the whole budget in 1975. Under the Rome Treaties, the Parliament should have become elected. However, the Council was required to agree a uniform voting system beforehand, which it failed to do. The Parliament threatened to take the Council to the European Court of Justice; this led to a compromise whereby the Council would agree to elections, but the issue of voting systems would be put off until a later date.

Elected Parliament

In 1979, its members were directly elected for the first time. This sets it apart from similar institutions such as those of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe or Pan-African Parliament which are appointed. After that first election, the parliament held its first session on 17 July 1979, electing Simone Veil MEP as its president. Veil was also the first female president of the Parliament since it was formed as the Common Assembly.

As an elected body, the Parliament began to draft proposals addressing the functioning of the EU. For example, in 1984, inspired by its previous work on the Political Community, it drafted the "draft Treaty establishing the European Union" (also known as the 'Spinelli Plan' after its rapporteur Altiero Spinelli MEP). Although it was not adopted, many ideas were later implemented by other treaties. Furthermore, the Parliament began holding votes on proposed Commission Presidents from the 1980s, before it was given any formal right to veto.

Since it became an elected body, the membership of the European Parliament has simply expanded whenever new nations have joined (the membership was also adjusted upwards in 1994 after German reunification). Following this, the Treaty of Nice imposed a cap on the number of members to be elected: 732.

Like the other institutions, the Parliament's seat was not yet fixed. The provisional arrangements placed Parliament in Strasbourg, while the Commission and Council had their seats in Brussels. In 1985 the Parliament, wishing to be closer to these institutions, built a second chamber in Brussels and moved some of its work there despite protests from some states. A final agreement was eventually reached by the European Council in 1992. It stated the Parliament would retain its formal seat in Strasbourg, where twelve sessions a year would be held, but with all other parliamentary activity in Brussels. This two-seat arrangement was contested by the Parliament, but was later enshrined in the Treaty of Amsterdam. To this day the institution's locations are a source of contention.

The Parliament gained more powers from successive treaties, namely through the extension of the ordinary legislative procedure (then called the codecision procedure), and in 1999, the Parliament forced the resignation of the Santer Commission. The Parliament had refused to approve the Community budget over allegations of fraud and mis-management in the Commission. The two main parties took on a government-opposition dynamic for the first time during the crisis which ended in the Commission resigning en masse, the first of any forced resignation, in the face of an impending censure from the Parliament.

Parliament pressure on the Commission

In 2004, following the largest trans-national election in history, despite the European Council choosing a President from the largest political group (the EPP), the Parliament again exerted pressure on the Commission. During the Parliament's hearings of the proposed Commissioners MEPs raised doubts about some nominees with the Civil Liberties committee rejecting Rocco Buttiglione from the post of Commissioner for Justice, Freedom and Security over his views on homosexuality. That was the first time the Parliament had ever voted against an incoming Commissioner and despite Barroso's insistence upon Buttiglione the Parliament forced Buttiglione to be withdrawn. A number of other Commissioners also had to be withdrawn or reassigned before Parliament allowed the Barroso Commission to take office.

Along with the extension of the ordinary legislative procedure, the Parliament's democratic mandate has given it greater control over legislation against the other institutions. In voting on the Bolkestein directive in 2006, the Parliament voted by a large majority for over 400 amendments that changed the fundamental principle of the law. The Financial Times described it in the following terms:

That is where the European parliament has suddenly come into its own. It marks another shift in power between the three central EU institutions. Last week's vote suggests that the directly elected MEPs, in spite of their multitude of ideological, national and historical allegiances, have started to coalesce as a serious and effective EU institution, just as enlargement has greatly complicated negotiations inside both the Council and Commission.

— "How the European parliament got serious", Financial Times (23 February 2006)

In 2007, for the first time, Justice Commissioner Franco Frattini included Parliament in talks on the second Schengen Information System even though MEPs only needed to be consulted on parts of the package. After that experiment, Frattini indicated he would like to include Parliament in all justice and criminal matters, informally pre-empting the new powers they could gain as part of the Treaty of Lisbon. Between 2007 and 2009, a special working group on parliamentary reform implemented a series of changes to modernise the institution such as more speaking time for rapporteurs, increase committee co-operation and other efficiency reforms.

Recent history

The Lisbon Treaty finally came into force on 1 December 2009, granting Parliament powers over the entire EU budget, making Parliament's legislative powers equal to the Council's in nearly all areas and linking the appointment of the Commission President to Parliament's own elections. Despite some calls for the parties to put forward candidates beforehand, only the EPP (which had re-secured their position as largest party) had one in re-endorsing Barroso.

Barroso gained the support of the European Council for a second term and secured majority support from the Parliament in September 2009. Parliament voted 382 votes in favour and 219 votes against (117 abstentions ) with support of the European People's Party, European Conservatives and Reformists and the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe. The liberals gave support after Barroso gave them a number of concessions; the liberals previously joined the socialists' call for a delayed vote (the EPP had wanted to approve Barroso in July of that year).

Once Barroso put forward the candidates for his next Commission, another opportunity to gain concessions arose. Bulgarian nominee Rumiana Jeleva was forced to step down by Parliament due to concerns over her experience and financial interests. She only had the support of the EPP which began to retaliate on left wing candidates before Jeleva gave in and was replaced (setting back the final vote further).

Before the final vote, Parliament demanded a number of concessions as part of a future working agreement under the new Lisbon Treaty. The deal includes that Parliament's President will attend high level Commission meetings. Parliament will have a seat in the EU's Commission-led international negotiations and have a right to information on agreements. However, Parliament secured only an observer seat. Parliament also did not secure a say over the appointment of delegation heads and special representatives for foreign policy. Although they will appear before parliament after they have been appointed by the High Representative. One major internal power was that Parliament wanted a pledge from the Commission that it would put forward legislation when parliament requests. Barroso considered this an infringement on the Commission's powers but did agree to respond within three months. Most requests are already responded to positively.

During the setting up of the European External Action Service (EEAS), Parliament used its control over the EU budget to influence the shape of the EEAS. MEPs had aimed at getting greater oversight over the EEAS by linking it to the Commission and having political deputies to the High Representative. MEPs didn't manage to get everything they demanded. However, they got broader financial control over the new body. In January 2019, Conservative MEPs supported proposals to boost opportunities for women and tackle sexual harassment in the European Parliament.

Powers and functions

The Parliament and Council have been compared to the two chambers of a bicameral legislature. However, there are some differences from national legislatures; for example, neither the Parliament nor the Council have the power of legislative initiative (except for the fact that the Council has the power in some intergovernmental matters). In Community matters, this is a power uniquely reserved for the European Commission (the executive). Therefore, while Parliament can amend and reject legislation, to make a proposal for legislation, it needs the Commission to draft a bill before anything can become law. The value of such a power has been questioned by noting that in the national legislatures of the member states 85% of initiatives introduced without executive support fail to become law. Yet it has been argued by former Parliament president Hans-Gert Pöttering that as the Parliament does have the right to ask the Commission to draft such legislation, and as the Commission is following Parliament's proposals more and more Parliament does have a de facto right of legislative initiative.

The Parliament also has a great deal of indirect influence, through non-binding resolutions and committee hearings, as a "pan-European soapbox" with the ear of thousands of Brussels-based journalists. There is also an indirect effect on foreign policy; the Parliament must approve all development grants, including those overseas. For example, the support for post-war Iraq reconstruction, or incentives for the cessation of Iranian nuclear development, must be supported by the Parliament. Parliamentary support was also required for the transatlantic passenger data-sharing deal with the United States. Finally, Parliament holds a non-binding vote on new EU treaties but cannot veto it. However, when Parliament threatened to vote down the Nice Treaty, the Belgian and Italian Parliaments said they would veto the treaty on the European Parliament's behalf.

Legislative procedure

With each new treaty, the powers of the Parliament, in terms of its role in the Union's legislative procedures, have expanded. The procedure which has slowly become dominant is the "ordinary legislative procedure" (previously named "codecision procedure"), which provides an equal footing between Parliament and Council. In particular, under the procedure, the Commission presents a proposal to Parliament and the Council which can only become law if both agree on a text, which they do (or not) through successive readings up to a maximum of three. In its first reading, Parliament may send amendments to the Council which can either adopt the text with those amendments or send back a "common position". That position may either be approved by Parliament, or it may reject the text by an absolute majority, causing it to fail, or it may adopt further amendments, also by an absolute majority. If the Council does not approve these, then a "Conciliation Committee" is formed. The Committee is composed of the Council members plus an equal number of MEPs who seek to agree a compromise. Once a position is agreed, it has to be approved by Parliament, by a simple majority. This is also aided by Parliament's mandate as the only directly democratic institution, which has given it leeway to have greater control over legislation than other institutions, for example over its changes to the Bolkestein directive in 2006.

The few other areas that operate the special legislative procedures are justice and home affairs, budget and taxation, and certain aspects of other policy areas, such as the fiscal aspects of environmental policy. In these areas, the Council or Parliament decide law alone. The procedure also depends upon which type of institutional act is being used. The strongest act is a regulation, an act or law which is directly applicable in its entirety. Then there are directives which bind member states to certain goals which they must achieve. They do this through their own laws and hence have room to manoeuvre in deciding upon them. A decision is an instrument which is focused at a particular person or group and is directly applicable. Institutions may also issue recommendations and opinions which are merely non-binding, declarations. There is a further document which does not follow normal procedures, this is a "written declaration" which is similar to an early day motion used in the Westminster system. It is a document proposed by up to five MEPs on a matter within the EU's activities used to launch a debate on that subject. Having been posted outside the entrance to the hemicycle, members can sign the declaration and if a majority do so it is forwarded to the President and announced to the plenary before being forwarded to the other institutions and formally noted in the minutes.

Budget

The legislative branch officially holds the Union's budgetary authority with powers gained through the Budgetary Treaties of the 1970s and the Lisbon Treaty. The EU budget is subject to a form of the ordinary legislative procedure with a single reading giving Parliament power over the entire budget (before 2009, its influence was limited to certain areas) on an equal footing to the Council. If there is a disagreement between them, it is taken to a conciliation committee as it is for legislative proposals. If the joint conciliation text is not approved, the Parliament may adopt the budget definitively.

The Parliament is also responsible for discharging the implementation of previous budgets based on the annual report of the European Court of Auditors. It has refused to approve the budget only twice, in 1984 and in 1998. On the latter occasion it led to the resignation of the Santer Commission; highlighting how the budgetary power gives Parliament a great deal of power over the Commission. Parliament also makes extensive use of its budgetary, and other powers, elsewhere; for example in the setting up of the European External Action Service, Parliament has a de facto veto over its design as it has to approve the budgetary and staff changes.

Control of the executive

The President of the European Commission is proposed by the European Council on the basis of the European elections to Parliament. That proposal has to be approved by the Parliament (by a simple majority) who "elect" the President according to the treaties. Following the approval of the Commission President, the members of the Commission are proposed by the President in accord with the member states. Each Commissioner comes before a relevant parliamentary committee hearing covering the proposed portfolio. They are then, as a body, approved or rejected by the Parliament.

In practice, the Parliament has never voted against a President or his Commission, but it did seem likely when the Barroso Commission was put forward. The resulting pressure forced the proposal to be withdrawn and changed to be more acceptable to parliament. That pressure was seen as an important sign by some of the evolving nature of the Parliament and its ability to make the Commission accountable, rather than being a rubber stamp for candidates. Furthermore, in voting on the Commission, MEPs also voted along party lines, rather than national lines, despite frequent pressure from national governments on their MEPs. This cohesion and willingness to use the Parliament's power ensured greater attention from national leaders, other institutions and the public – who previously gave the lowest ever turnout for the Parliament's elections.

The Parliament also has the power to censure the Commission if they have a two-thirds majority which will force the resignation of the entire Commission from office. As with approval, this power has never been used but it was threatened to the Santer Commission, who subsequently resigned of their own accord. There are a few other controls, such as: the requirement of Commission to submit reports to the Parliament and answer questions from MEPs; the requirement of the President-in-office of the Council to present its programme at the start of their presidency; the obligation on the President of the European Council to report to Parliament after each of its meetings; the right of MEPs to make requests for legislation and policy to the Commission; and the right to question members of those institutions (e.g. "Commission Question Time" every Tuesday). At present, MEPs may ask a question on any topic whatsoever, but in July 2008 MEPs voted to limit questions to those within the EU's mandate and ban offensive or personal questions.

Supervisory powers

The Parliament also has other powers of general supervision, mainly granted by the Maastricht Treaty. The Parliament has the power to set up a Committee of Inquiry, for example over mad cow disease or CIA detention flights – the former led to the creation of the European veterinary agency. The Parliament can call other institutions to answer questions and if necessary to take them to court if they break EU law or treaties. Furthermore, it has powers over the appointment of the members of the Court of Auditors and the president and executive board of the European Central Bank. The ECB president is also obliged to present an annual report to the parliament.

The European Ombudsman is elected by the Parliament, who deals with public complaints against all institutions. Petitions can also be brought forward by any EU citizen on a matter within the EU's sphere of activities. The Committee on Petitions hears cases, some 1500 each year, sometimes presented by the citizen themselves at the Parliament. While the Parliament attempts to resolve the issue as a mediator they do resort to legal proceedings if it is necessary to resolve the citizens dispute.

Members

|

The parliamentarians are known in English as Members of the European Parliament (MEPs). They are elected every five years by universal adult suffrage and sit according to political allegiance; about one third are women. Before 1979 they were appointed by their national parliaments.

The Parliament has been criticized for underrepresentation of minority groups. In 2017, an estimated 17 MEPs were nonwhite, and of these, three were black, a disproportionately low number. According to activist organization European Network Against Racism, while an estimated 10% of Europe is composed of racial and ethnic minorities, only 5% of MEPs were members of such groups following the 2019 European Parliament election.

Under the Lisbon Treaty, seats are allocated to each state according to population and the maximum number of members is set at 751 (however, as the President cannot vote while in the chair there will only be 750 voting members at any one time). Since 1 February 2020, 705 MEPs (including the president of the Parliament) sit in the European Parliament, the reduction in size due to the United Kingdom leaving the EU.

Representation is currently limited to a maximum of 96 seats and a minimum of 6 seats per state and the seats are distributed according to "degressive proportionality", i.e., the larger the state, the more citizens are represented per MEP. As a result, Maltese and Luxembourgish voters have roughly 10x more influence per voter than citizens of the six large countries.

As of 2014, Germany (80.9 million inhabitants) has 96 seats (previously 99 seats), i.e. one seat for 843,000 inhabitants. Malta (0.4 million inhabitants) has 6 seats, i.e. one seat for 70,000 inhabitants.

The new system implemented under the Lisbon Treaty, including revising the seating well before elections, was intended to avoid political horse trading when the allocations have to be revised to reflect demographic changes.

Pursuant to this apportionment, the constituencies are formed. In four EU member states (Belgium, Ireland, Italy and Poland), the national territory is divided into a number of constituencies. In the remaining member states, the whole country forms a single constituency. All member states hold elections to the European Parliament using various forms of proportional representation.

Transitional arrangements

Due to the delay in ratifying the Lisbon Treaty, the seventh parliament was elected under the lower Nice Treaty cap. A small scale treaty amendment was ratified on 29 November 2011. This amendment brought in transitional provisions to allow the 18 additional MEPs created under the Lisbon Treaty to be elected or appointed before the 2014 election. Under the Lisbon Treaty reforms, Germany was the only state to lose members from 99 to 96. However, these seats were not removed until the 2014 election.

Salaries and expenses

Before 2009, members received the same salary as members of their national parliament. However, from 2009 a new members statute came into force, after years of attempts, which gave all members an equal monthly pay, of €8,484.05 each in 2016, subject to a European Union tax and which can also be taxed nationally. MEPs are entitled to a pension, paid by Parliament, from the age of 63. Members are also entitled to allowances for office costs and subsistence, and travelling expenses, based on actual cost. Besides their pay, members are granted a number of privileges and immunities. To ensure their free movement to and from the Parliament, they are accorded by their own states the facilities accorded to senior officials travelling abroad and, by other state governments, the status of visiting foreign representatives. When in their own state, they have all the immunities accorded to national parliamentarians, and, in other states, they have immunity from detention and legal proceedings. However, immunity cannot be claimed when a member is found committing a criminal offence and the Parliament also has the right to strip a member of their immunity.

Political groups

MEPs in Parliament are organised into eight different parliamentary groups, including thirty non-attached members known as non-inscrits. The two largest groups are the European People's Party (EPP) and the Socialists & Democrats (S&D). These two groups have dominated the Parliament for much of its life, continuously holding between 50 and 70 percent of the seats between them. No single group has ever held a majority in Parliament. As a result of being broad alliances of national parties, European group parties are very decentralised and hence have more in common with parties in federal states like Germany or the United States than unitary states like the majority of the EU states. Nevertheless, the European groups were actually more cohesive than their US counterparts between 2004 and 2009.

Groups are often based on a single European political party such as the European People's Party. However, they can, like the liberal group, include more than one European party as well as national parties and independents. For a group to be recognised, it needs 25 MEPs from seven different countries. Once recognised, groups receive financial subsidies from the parliament and guaranteed seats on committees, creating an incentive for the formation of groups.

Grand coalition

Given that the Parliament does not form the government in the traditional sense of a Parliamentary system, its politics have developed along more consensual lines rather than majority rule of competing parties and coalitions. Indeed, for much of its life it has been dominated by a grand coalition of the European People's Party and the Party of European Socialists. The two major parties tend to co-operate to find a compromise between their two groups leading to proposals endorsed by huge majorities. However, this does not always produce agreement, and each may instead try to build other alliances, the EPP normally with other centre-right or right wing Groups and the PES with centre-left or left wing groups. Sometimes, the Liberal Group is then in the pivotal position. There are also occasions where very sharp party political divisions have emerged, for example over the resignation of the Santer Commission.

When the initial allegations against the Commission emerged, they were directed primarily against Édith Cresson and Manuel Marín, both socialist members. When the parliament was considering refusing to discharge the Community budget, President Jacques Santer stated that a no vote would be tantamount to a vote of no confidence. The Socialist group supported the Commission and saw the issue as an attempt by the EPP to discredit their party ahead of the 1999 elections. Socialist leader, Pauline Green MEP, attempted a vote of confidence and the EPP put forward counter motions. During this period the two parties took on similar roles to a government-opposition dynamic, with the Socialists supporting the executive and EPP renouncing its previous coalition support and voting it down. Politicisation such as this has been increasing, in 2007 Simon Hix of the London School of Economics noted that:

Our work also shows that politics in the European Parliament is becoming increasingly based around party and ideology. Voting is increasingly split along left-right lines, and the cohesion of the party groups has risen dramatically, particularly in the fourth and fifth parliaments. So there are likely to be policy implications here too.

During the fifth term, 1999 to 2004, there was a break in the grand coalition resulting in a centre-right coalition between the Liberal and People's parties. This was reflected in the Presidency of the Parliament with the terms being shared between the EPP and the ELDR, rather than the EPP and Socialists. In the following term the liberal group grew to hold 88 seats, the largest number of seats held by any third party in Parliament.

Elections

| |||||||

Elections have taken place, directly in every member state, every five years since 1979. As of 2019 there have been nine elections. When a nation joins mid-term, a by-election will be held to elect their representatives. This has happened six times, most recently when Croatia joined in 2013. Elections take place across four days according to local custom and, apart from having to be proportional, the electoral system is chosen by the member state. This includes allocation of sub-national constituencies; while most members have a national list, some, like the UK and Poland, divide their allocation between regions. Seats are allocated to member states according to their population, since 2014 with no state having more than 96, but no fewer than 6, to maintain proportionality.

The most recent Union-wide elections to the European Parliament were the European elections of 2019, held from 23 to 26 May 2019. They were the largest simultaneous transnational elections ever held anywhere in the world. The first session of the ninth parliament started 2 July 2019.

European political parties have the exclusive right to campaign during the European elections (as opposed to their corresponding EP groups). There have been a number of proposals designed to attract greater public attention to the elections. One such innovation in the 2014 elections was that the pan-European political parties fielded "candidates" for president of the Commission, the so-called Spitzenkandidaten (German, "leading candidates" or "top candidates"). However, European Union governance is based on a mixture of intergovernmental and supranational features: the President of the European Commission is nominated by the European Council, representing the governments of the member states, and there is no obligation for them to nominate the successful "candidate". The Lisbon Treaty merely states that they should take account of the results of the elections when choosing whom to nominate. The so-called Spitzenkandidaten were Jean-Claude Juncker for the European People's Party, Martin Schulz for the Party of European Socialists, Guy Verhofstadt for the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Party, Ska Keller and José Bové jointly for the European Green Party and Alexis Tsipras for the Party of the European Left.

Turnout dropped consistently every year since the first election, and from 1999 until 2019 was below 50%. In 2007 both Bulgaria and Romania elected their MEPs in by-elections, having joined at the beginning of 2007. The Bulgarian and Romanian elections saw two of the lowest turnouts for European elections, just 28.6% and 28.3% respectively. This trend was interrupted in the 2019 election, when turnout increased by 8% EU-wide, rising to 50.6%, the highest since 1994.

In England, Scotland and Wales, EP elections were originally held for a constituency MEP on a first-past-the-post basis. In 1999 the system was changed to a form of PR where a large group of candidates stand for a post within a very large regional constituency. One can vote for a party, but not a candidate (unless that party has a single candidate).

Proceedings

Each year the activities of the Parliament cycle between committee weeks where reports are discussed in committees and interparliamentary delegations meet, political group weeks for members to discuss work within their political groups and session weeks where members spend 3½ days in Strasbourg for part-sessions. In addition six 2-day part-sessions are organised in Brussels throughout the year. Four weeks are allocated as constituency week to allow members to do exclusively constituency work. Finally there are no meetings planned during the summer weeks. The Parliament has the power to meet without being convened by another authority. Its meetings are partly controlled by the treaties but are otherwise up to Parliament according to its own "Rules of Procedure" (the regulations governing the parliament).

During sessions, members may speak after being called on by the President. Members of the Council or Commission may also attend and speak in debates. Partly due to the need for interpretation, and the politics of consensus in the chamber, debates tend to be calmer and more polite than, say, the Westminster system. Voting is conducted primarily by a show of hands, that may be checked on request by electronic voting. Votes of MEPs are not recorded in either case, however; that only occurs when there is a roll-call ballot. This is required for the final votes on legislation and also whenever a political group or 30 MEPs request it. The number of roll-call votes has increased with time. Votes can also be a completely secret ballot (for example, when the president is elected). All recorded votes, along with minutes and legislation, are recorded in the Official Journal of the European Union and can be accessed online. Votes usually do not follow a debate, but rather they are grouped with other due votes on specific occasions, usually at noon on Tuesdays, Wednesdays or Thursdays. This is because the length of the vote is unpredictable and if it continues for longer than allocated it can disrupt other debates and meetings later in the day.

Members are arranged in a hemicycle according to their political groups (in the Common Assembly, prior to 1958, members sat alphabetically) who are ordered mainly by left to right, but some smaller groups are placed towards the outer ring of the Parliament. All desks are equipped with microphones, headphones for translation and electronic voting equipment. The leaders of the groups sit on the front benches at the centre, and in the very centre is a podium for guest speakers. The remaining half of the circular chamber is primarily composed of the raised area where the President and staff sit. Further benches are provided between the sides of this area and the MEPs, these are taken up by the Council on the far left and the Commission on the far right. Both the Brussels and Strasbourg hemicycle roughly follow this layout with only minor differences. The hemicycle design is a compromise between the different Parliamentary systems. The British-based system has the different groups directly facing each other while the French-based system is a semicircle (and the traditional German system had all members in rows facing a rostrum for speeches). Although the design is mainly based on a semicircle, the opposite ends of the spectrum do still face each other. With access to the chamber limited, entrance is controlled by ushers who aid MEPs in the chamber (for example in delivering documents). The ushers can also occasionally act as a form of police in enforcing the President, for example in ejecting an MEP who is disrupting the session (although this is rare). The first head of protocol in the Parliament was French, so many of the duties in the Parliament are based on the French model first developed following the French Revolution. The 180 ushers are highly visible in the Parliament, dressed in black tails and wearing a silver chain, and are recruited in the same manner as the European civil service. The President is allocated a personal usher.

President and organisation

The President is essentially the speaker of the Parliament and presides over the plenary when it is in session. The President's signature is required for all acts adopted by co-decision, including the EU budget. The President is also responsible for representing the Parliament externally, including in legal matters, and for the application of the rules of procedure. He or she is elected for two-and-a-half-year terms, meaning two elections per parliamentary term. The President is currently David Sassoli (S&D).

In most countries, the protocol of the head of state comes before all others; however, in the EU the Parliament is listed as the first institution, and hence the protocol of its president comes before any other European, or national, protocol. The gifts given to numerous visiting dignitaries depend upon the President. President Josep Borrell MEP of Spain gave his counterparts a crystal cup created by an artist from Barcelona who had engraved upon it parts of the Charter of Fundamental Rights among other things.

A number of notable figures have been President of the Parliament and its predecessors. The first President was Paul-Henri Spaak MEP, one of the founding fathers of the Union. Other founding fathers include Alcide de Gasperi MEP and Robert Schuman MEP. The two female Presidents were Simone Veil MEP in 1979 (first President of the elected Parliament) and Nicole Fontaine MEP in 1999, both Frenchwomen. The previous president, Jerzy Buzek was the first East-Central European to lead an EU institution, a former Prime Minister of Poland who rose out of the Solidarity movement in Poland that helped overthrow communism in the Eastern Bloc.

During the election of a President, the previous President (or, if unable to, one of the previous Vice-Presidents) presides over the chamber. Prior to 2009, the oldest member fulfilled this role but the rule was changed to prevent far-right French MEP Jean-Marie Le Pen taking the chair.

Below the President, there are 14 Vice-Presidents who chair debates when the President is not in the chamber. There are a number of other bodies and posts responsible for the running of parliament besides these speakers. The two main bodies are the Bureau, which is responsible for budgetary and administration issues, and the Conference of Presidents which is a governing body composed of the presidents of each of the parliament's political groups. Looking after the financial and administrative interests of members are five Quaestors.

As of 2014, the European Parliament budget was EUR 1.756 billion. A 2008 report on the Parliament's finances highlighted certain overspending and miss-payments. Despite some MEPs calling for the report to be published, Parliamentary authorities had refused until an MEP broke confidentiality and leaked it.

Committees and delegations

The Parliament has 20 Standing Committees consisting of 25 to 73 MEPs each (reflecting the political make-up of the whole Parliament) including a chair, a bureau and secretariat. They meet twice a month in public to draw up, amend to adopt legislative proposals and reports to be presented to the plenary. The rapporteurs for a committee are supposed to present the view of the committee, although notably this has not always been the case. In the events leading to the resignation of the Santer Commission, the rapporteur went against the Budgetary Control Committee's narrow vote to discharge the budget, and urged the Parliament to reject it.

Committees can also set up sub-committees (e.g. the Subcommittee on Human Rights) and temporary committees to deal with a specific topic (e.g. on extraordinary rendition). The chairs of the Committees co-ordinate their work through the "Conference of Committee Chairmen". When co-decision was introduced it increased the Parliament's powers in a number of areas, but most notably those covered by the Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety. Previously this committee was considered by MEPs as a "Cinderella committee"; however, as it gained a new importance, it became more professional and rigorous, attracting increasing attention to its work.

The nature of the committees differ from their national counterparts as, although smaller in comparison to those of the United States Congress, the European Parliament's committees are unusually large by European standards with between eight and twelve dedicated members of staff and three to four support staff. Considerable administration, archives and research resources are also at the disposal of the whole Parliament when needed.

Delegations of the Parliament are formed in a similar manner and are responsible for relations with Parliaments outside the EU. There are 34 delegations made up of around 15 MEPs, chairpersons of the delegations also cooperate in a conference like the committee chairs do. They include "Interparliamentary delegations" (maintain relations with Parliament outside the EU), "joint parliamentary committees" (maintaining relations with parliaments of states which are candidates or associates of the EU), the delegation to the ACP EU Joint Parliamentary Assembly and the delegation to the Euro-Mediterranean Parliamentary Assembly. MEPs also participate in other international activities such as the Euro-Latin American Parliamentary Assembly, the Transatlantic Legislators' Dialogue and through election observation in third countries.

Intergroups

The Intergroups in the European Parliament are informal fora which gather MEPs from various political groups around any topic. They do not express the view of the European Parliament. They serve a double purpose: to address a topic which is transversal to several committees and in a less formal manner. Their daily secretariat can be run either through the office of MEPs or through interest groups, be them corporate lobbies or NGOs. The favored access to MEPs which the organization running the secretariat enjoys can be one explanation to the multiplication of Intergroups in the 1990s. They are now strictly regulated and financial support, direct or otherwise (via Secretariat staff, for example) must be officially specified in a declaration of financial interests. Also Intergroups are established or renewed at the beginning of each legislature through a specific process. Indeed, the proposal for the constitution or renewal of an Intergroup must be supported by at least 3 political groups whose support is limited to a specific number of proposals in proportion to their size (for example, for the legislature 2014-2019, the EPP or S&D political groups could support 22 proposals whereas the Greens/EFA or the EFDD political groups only 7).

Translation and interpretation

Speakers in the European Parliament are entitled to speak in any of the 24 official languages of the European Union, ranging from French and German to Maltese and Irish. Simultaneous interpreting is offered in all plenary sessions, and all final texts of legislation are translated. With twenty-four languages, the European Parliament is the most multilingual parliament in the world and the biggest employer of interpreters in the world (employing 350 full-time and 400 free-lancers when there is higher demand). Citizens may also address the Parliament in Basque, Catalan/Valencian and Galician.

Usually a language is translated from a foreign tongue into a translator's native tongue. Due to the large number of languages, some being minor ones, since 1995 interpreting is sometimes done the opposite way, out of an interpreter's native tongue (the "retour" system). In addition, a speech in a minor language may be interpreted through a third language for lack of interpreters ("relay" interpreting) – for example, when interpreting out of Estonian into Maltese. Due to the complexity of the issues, interpretation is not word for word. Instead, interpreters have to convey the political meaning of a speech, regardless of their own views. This requires detailed understanding of the politics and terms of the Parliament, involving a great deal of preparation beforehand (e.g. reading the documents in question). Difficulty can often arise when MEPs use profanities, jokes and word play or speak too fast.

While some see speaking their native language as an important part of their identity, and can speak more fluently in debates, interpretation and its cost has been criticised by some. A 2006 report by Alexander Stubb MEP highlighted that by only using English, French and German costs could be reduced from €118,000 per day (for 21 languages then – Romanian, Bulgarian and Croatian having not yet been included) to €8,900 per day. There has also been a small-scale campaign to make French the reference language for all legal texts, on the basis of an argument that it is more clear and precise for legal purposes.

Because the proceedings are translated into all of the official EU languages, they have been used to make a multilingual corpus known as Europarl. It is widely used to train statistical machine translation systems.

Annual costs

According to the European Parliament website, the annual parliament budget for 2016 was €1.838 billion. The main cost categories were:

- 34% – staff, interpretation and translation costs

- 24% – information policy, IT, telecommunications

- 23% – MEPs' salaries, expenses, travel, offices and staff

- 13% – buildings

- 6% – political group activities

According to a European Parliament study prepared in 2013, the Strasbourg seat costs an extra €103 million over maintaining a single location and according to the Court of Auditors an additional €5 million is related to travel expenses caused by having two seats.

As a comparison, the German lower house of parliament (Bundestag) is estimated to cost €517 million in total for 2018, for a parliament with 709 members. The British House of Commons reported total annual costs in 2016-2017 of £249 million (€279 million). It had 650 seats.

According to The Economist, the European Parliament costs more than the British, French and German parliaments combined. A quarter of the costs is estimated to be related to translation and interpretation costs (c. €460 million) and the double seats are estimated to add an additional €180 million a year. For a like-for-like comparison, these two cost blocks can be excluded.

On 2 July 2018, MEPs rejected proposals to tighten the rules around the General Expenditure Allowance (GEA), which "is a controversial €4,416 per month payment that MEPs are given to cover office and other expenses, but they are not required to provide any evidence of how the money is spent".

Seat

The Parliament is based in three different cities with numerous buildings. A protocol attached to the Treaty of Amsterdam requires that 12 plenary sessions be held in Strasbourg (none in August but two in September), which is the Parliament's official seat, while extra part sessions as well as committee meetings are held in Brussels. Luxembourg City hosts the Secretariat of the European Parliament. The European Parliament is one of at least two assemblies in the world with more than one meeting place (another being the parliament of the Isle of Man, Tynwald) and one of the few that does not have the power to decide its own location.

The Strasbourg seat is seen as a symbol of reconciliation between France and Germany, the Strasbourg region having been fought over by the two countries in the past. However, the cost and inconvenience of having two seats is questioned. While Strasbourg is the official seat, and sits alongside the Council of Europe, Brussels is home to nearly all other major EU institutions, with the majority of Parliament's work being carried out there. Critics have described the two-seat arrangement as a "travelling circus", and there is a strong movement to establish Brussels as the sole seat. This is because the other political institutions (the Commission, Council and European Council) are located there, and hence Brussels is treated as the 'capital' of the EU. This movement has received strong backing from numerous figures, including Margot Wallström, Commission First-Vice President from 2004 to 2010, who stated that "something that was once a very positive symbol of the EU reuniting France and Germany has now become a negative symbol – of wasting money, bureaucracy and the insanity of the Brussels institutions". The Green Party has also noted the environmental cost in a study led by Jean Lambert MEP and Caroline Lucas MEP; in addition to the extra 200 million euro spent on the extra seat, there are over 20,268 tonnes of additional carbon dioxide, undermining any environmental stance of the institution and the Union. The campaign is further backed by a million-strong online petition started by Cecilia Malmström MEP. In August 2014, an assessment by the European Court of Auditors calculated that relocating the Strasbourg seat of the European Parliament to Brussels would save €113.8 million per year. In 2006, there were allegations of irregularities in the charges made by the city of Strasbourg on buildings the Parliament rented, thus further harming the case for the Strasbourg seat.

Most MEPs prefer Brussels as a single base. A poll of MEPs found 89% of the respondents wanting a single seat, and 81% preferring Brussels. Another, more academic, survey found 68% support. In July 2011, an absolute majority of MEPs voted in favour of a single seat. In early 2011, the Parliament voted to scrap one of the Strasbourg sessions by holding two within a single week. The mayor of Strasbourg officially reacted by stating "we will counter-attack by upturning the adversary's strength to our own profit, as a judoka would do". However, as Parliament's seat is now fixed by the treaties, it can only be changed by the Council acting unanimously, meaning that France could veto any move. The former French President Nicolas Sarkozy has stated that the Strasbourg seat is "non-negotiable", and that France has no intention of surrendering the only EU Institution on French soil. Given France's declared intention to veto any relocation to Brussels, some MEPs have advocated civil disobedience by refusing to take part in the monthly exodus to Strasbourg.

Channels of dialogue, information, and communication with European civil society

Over the last few years, European institutions have committed to promoting transparency, openness, and the availability of information about their work. In particular, transparency is regarded as pivotal to the action of European institutions and a general principle of EU law, to be applied to the activities of EU institutions in order to strengthen the Union's democratic foundation. The general principles of openness and transparency are reaffirmed in the articles 8 A, point 3 and 10.3 of the Treaty of Lisbon and the Maastricht Treaty respectively, stating that "every citizen shall have the right to participate in the democratic life of the Union. Decisions shall be taken as openly and as closely as possible to the citizen". Furthermore, both treaties acknowledge the value of dialogue between citizens, representative associations, civil society, and European institutions.

Dialogue with religious and non-confessional organisations

Article 17 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) lays the juridical foundation for an open, transparent dialogue between European institutions and churches, religious associations, and non-confessional and philosophical organisations. In July 2014, in the beginning of the 8th term, then President of the European Parliament Martin Schulz tasked Antonio Tajani, then Vice-President, with implementing the dialogue with the religious and confessional organisations included in article 17. In this framework, the European Parliament hosts high-level conferences on inter-religious dialogue, also with focus on current issues and in relation with parliamentary works.

European Parliament Mediator for International Parental Child Abduction

The chair of European Parliament Mediator for International Parental Child Abduction was established in 1987 by initiative of British MEP Charles Henry Plumb, with the goal of helping minor children of international couples victim of parental abduction. The Mediator finds negotiated solutions in the higher interest of the minor when said minor is abducted by a parent following separation of the couple, regardless whether married or unmarried. Since its institution, the chair has been held by Mairead McGuinness (since 2014), Roberta Angelilli (2009–2014), Evelyne Gebhardt (2004–2009), Mary Banotti (1995–2004), and Marie-Claude Vayssade (1987–1994). The Mediator's main task is to assist parents in finding a solution in the minor's best interest through mediation, i.e. a form of controversy resolution alternative to lawsuit. The Mediator is activated by request of a citizen and, after evaluating the request, starts a mediation process aimed at reaching an agreement. Once subscribed by both parties and the Mediator, the agreement is official. The nature of the agreement is that of a private contract between parties. In defining the agreement, the European Parliament offers the parties the juridical support necessary to reach a sound, lawful agreement based on legality and equity. The agreement can be ratified by the competent national courts and can also lay the foundation for consensual separation or divorce.

European Parliamentary Research Service

The European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS) is the European Parliament's in-house research department and think tank. It provides Members of the European Parliament – and, where appropriate, parliamentary committees – with independent, objective and authoritative analysis of, and research on, policy issues relating to the European Union, in order to assist them in their parliamentary work. It is also designed to increase Members' and EP committees' capacity to scrutinise and oversee the European Commission and other EU executive bodies.

EPRS aims to provide a comprehensive range of products and services, backed by specialist internal expertise and knowledge sources in all policy fields, so empowering Members and committees through knowledge and contributing to the Parliament's effectiveness and influence as an institution. In undertaking this work, the EPRS supports and promotes parliamentary outreach to the wider public, including dialogue with relevant stakeholders in the EU’s system of multi-level governance. All publications by EPRS are publicly available on the EP Think Tank platform.

Eurobarometer of the European Parliament

The European Parliament periodically commissions opinion polls and studies on public opinion trends in Member States to survey perceptions and expectations of citizens about its work and the overall activities of the European Union. Topics include citizens' perception of the European Parliament's role, their knowledge of the institution, their sense of belonging in the European Union, opinions on European elections and European integration, identity, citizenship, political values, but also on current issues such as climate change, current economy and politics, etc.. Eurobarometer analyses seek to provide an overall picture of national situations, regional specificities, socio-demographic cleavages, and historical trends.

Prizes

Sakharov Prize

With the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, created in 1998, the European Parliament supports human rights by awarding individuals that contribute to promoting human rights worldwide, thus raising awareness on human rights violations. Priorities include: protection of human rights and fundamental liberties, with particular focus on freedom of expression; protection of minority rights; compliance with international law; and development of democracy and authentic rule of law.

European Charlemagne Youth Prize

The European Charlemagne Youth Prize seeks to encourage youth participation in the European integration process. It is awarded by the European Parliament and the Foundation of the International Charlemagne Prize of Aachen to youth projects aimed at nurturing common European identity and European citizenship.

European Citizens' Prize

The European Citizens' Prize is awarded by the European Parliament to activities and actions carried out by citizens and associations to promote integration between the citizens of EU member states and transnational cooperation projects in the EU.

LUX Prize

Since 2007, the LUX Prize is awarded by the European Parliament to films dealing with current topics of public European interest that encourage reflection on Europe and its future. Over time, the Lux Prize has become a prestigious cinema award which supports European film and production also outside the EU.

Daphne Caruana Galizia Journalism Prize

From 2021, the Daphne Caruana Galizia Journalism prize shall be awarded by the European Parliament to outstanding journalism that reflect EU values. The prize consists in an award of 20,000 euros and the very first winner will be revealed in October 2021. This award is named after the late Maltese journalist, Daphne Caruana Galizia who was assassinated in Malta on 16 October 2017.