Details

During the presidency of Barack Obama, who campaigned heavily on accomplishing health care reform, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) was enacted in March 2010.

In the next administration, President Trump said the healthcare system should work based on free market principles. He endorsed a seven-point plan for healthcare reform:

- repeal Obamacare

- reduce barriers to the interstate sale of health insurance

- institute a full tax deduction for insurance premium payments for individuals

- make Health Saving Accounts inheritable

- require price transparency

- block-grant Medicaid to the states

- allow for more overseas drug providers through lowered regulatory barriers

He also suggested that enforcing immigration laws could reduce healthcare costs.

The Trump administration made efforts to repeal the ACA and replace it with a different healthcare policy (known as a "repeal and replace" approach), but it never succeeded in doing so through Congress. Next, the administration joined a lawsuit seeking to overturn the ACA, and the Supreme Court agreed at the beginning of March 2020 that it would hear the case. Under normal scheduling, the case would be heard in the fall of 2020 and decided in the spring of 2021. However, as the Supreme Court subsequently went on hiatus in response to the coronavirus pandemic, it is unclear when the case will be heard.

Cost debate

U.S. healthcare costs were approximately $3.2 trillion or nearly $10,000 per person on average in 2015. Major categories of expense include hospital care (32%), physician and clinical services (20%), and prescription drugs (10%). U.S. costs in 2016 were substantially higher than other OECD countries, at 17.2% GDP versus 12.4% GDP for the next most expensive country (Switzerland). For scale, a 5% GDP difference represents about $1 trillion or $3,000 per person. Some of the many reasons cited for the cost differential with other countries include: Higher administrative costs of a private system with multiple payment processes; higher costs for the same products and services; more expensive volume/mix of services with higher usage of more expensive specialists; aggressive treatment of very sick elderly versus palliative care; less use of government intervention in pricing; and higher income levels driving greater demand for healthcare. Healthcare costs are a fundamental driver of health insurance costs, which leads to coverage affordability challenges for millions of families. There is ongoing debate whether the current law (ACA/Obamacare) and the Republican alternatives (AHCA and BCRA) do enough to address the cost challenge.

In 2009, the U.S. had the highest health care costs relative to the size of the economy (GDP) in the world, with an estimated 50.2 million citizens (approximately 16% of the September 2011 estimated population of 312 million) without insurance coverage. Some critics of reform counter that almost four out of ten of these uninsured come from a household with over $50,000 income per year, and thus might be uninsured voluntarily, or opting to pay for health care services on a "pay-as-you-go" basis. Further, an estimated 77 million Baby Boomers are reaching retirement age, which combined with significant annual increases in healthcare costs per person will place enormous budgetary strain on U.S. state and federal governments. Maintaining the long-term fiscal health of the U.S. federal government is significantly dependent on healthcare costs being controlled.

Quality of care

There is significant debate regarding the quality of the U.S. healthcare system relative to those of other countries. Physicians for a National Health Program, a political advocacy group, has claimed that a free market solution to healthcare provides a lower quality of care, with higher mortality rates, than publicly funded systems. The quality of health maintenance organizations and managed care have also been criticized by this same group.

According to a 2015 report from The Commonwealth Fund, although the United States pays almost twice as much per capita towards healthcare as other wealthy countries with universal healthcare, patient outcomes are poorer. The United States has the lowest life expectancy overall and the infant mortality rate is the highest and in some cases twice as high when compared with other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. Also highlighted in this report is data that shows that although Americans have one of the lowest percentages of daily smokers, they have the highest mortality rate for heart disease, a significantly higher obesity rate and more amputations due to diabetes. Other health related issues highlighted were that Americans over the age of 65 have a higher percentage of the population with two or more chronic conditions and the lowest percentage of that age group living.

According to a 2000 study of the World Health Organization (WHO), publicly funded systems of industrial nations spend less on healthcare, both as a percentage of their GDP and per capita, and enjoy superior population-based health care outcomes. However, conservative commentator David Gratzer and the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank, have both criticized the WHO's comparison method for being biased; the WHO study marked down countries for having private or fee-paying health treatment and rated countries by comparison to their expected healthcare performance, rather than objectively comparing quality of care.

Some medical researchers say that patient satisfaction surveys are a poor way to evaluate medical care. Researchers at the RAND Corporation and the Department of Veterans Affairs asked 236 elderly patients in two different managed care plans to rate their care, then examined care in medical records, as reported in Annals of Internal Medicine. There was no correlation. "Patient ratings of health care are easy to obtain and report, but do not accurately measure the technical quality of medical care," said John T. Chang, UCLA, lead author.

There are health losses from insufficient health insurance. A 2009 Harvard study published in the American Journal of Public Health found more than 44,800 excess deaths annually in the United States due to Americans lacking health insurance. More broadly, estimates of the total number of people in the United States, whether insured or uninsured, who die because of lack of medical care were estimated in a 1997 analysis to be nearly 100,000 per year.

A 2007 article from The BMJ by Steffie Woolhandler and David Himmelstein strongly argued that the United States' healthcare model delivered inferior care at inflated prices, and further stated: "The poor performance of US health care is directly attributable to reliance on market mechanisms and for-profit firms and should warn other nations from this path."

Cost and efficiency

The United States spends a higher proportion of its GDP on healthcare (19%) than any other country in the world, except for East Timor (Timor-Leste). The number of employers who offer health insurance is declining. Costs for employer-paid health insurance are rising rapidly: since 2001, premiums for family coverage have increased 78%, while wages have risen 19% and prices have risen 17%, according to a 2007 study by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Private insurance in the US varies greatly in its coverage; one study by the Commonwealth Fund published in Health Affairs estimated that 16 million U.S. adults were underinsured in 2003. The underinsured were significantly more likely than those with adequate insurance to forgo healthcare, report financial stress because of medical bills, and experience coverage gaps for such items as prescription drugs. The study found that underinsurance disproportionately affects those with lower incomes – 73% of the underinsured in the study population had annual incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level.

However, a study published by the Kaiser Family Foundation in 2008 found that the typical large employer Preferred provider organization (PPO) plan in 2007 was more generous than either Medicare or the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program Standard Option. One indicator of the consequences of Americans' inconsistent health care coverage is a study in Health Affairs that concluded that half of personal bankruptcies involved medical bills, although other sources dispute this.

Proponents of healthcare reforms involving expansion of government involvement to achieve universal healthcare argue that the need to provide profits to investors in a predominantly free market health system, and the additional administrative spending, tends to drive up costs, leading to more expensive provision.

According to economist and former US Secretary of Labor, Robert Reich, only a "big, national, public option" can force insurance companies to cooperate, share information, and reduce costs. Scattered, localized, "insurance cooperatives" are too small to do that and are "designed to fail" by the moneyed forces opposing Democratic health care reform.

Impact on U.S. economic productivity

On March 1, 2010, billionaire Warren Buffett said that the high costs paid by U.S. companies for their employees’ healthcare put them at a competitive disadvantage. He compared the roughly 17% of GDP spent by the U.S. on healthcare with the 9% of GDP spent by much of the rest of the world, noted that the U.S. has fewer doctors and nurses per person, and said, “that kind of a cost, compared with the rest of the world, is like a tapeworm eating at our economic body.”

Allegations of waste

In December 2011 the outgoing Administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Dr. Donald Berwick, asserted that 20% to 30% of healthcare spending is waste. He listed five causes for the waste: (1) overtreatment of patients, (2) the failure to coordinate care, (3) the administrative complexity of the system, (4) burdensome rules and (5) fraud.

Ideas for reform

During a June 2009 speech, President Barack Obama outlined his strategy for reform. He mentioned electronic record-keeping, preventing expensive conditions, reducing obesity, refocusing doctor incentives from quantity of care to quality, bundling payments for treatment of conditions rather than specific services, better identifying and communicating the most cost-effective treatments, and reducing defensive medicine.

President Obama further described his plan in a September 2009 speech to a joint session of Congress. His plan mentions: deficit neutrality; not allowing insurance companies to discriminate based on pre-existing conditions; capping out of pocket expenses; creation of an insurance exchange for individuals and small businesses; tax credits for individuals and small companies; independent commissions to identify fraud, waste and abuse; and malpractice reform projects, among other topics.

OMB Director Peter Orszag described aspects of the Obama administration's strategy during an interview in November 2009: "In order to help contain [Medicare and Medicaid] cost growth over the long term, we need a new healthcare system that has digitized information... in which that information is used to assess what’s working and what’s not more intelligently, and in which we’re paying for quality rather than quantity while also encouraging prevention and wellness." He also argued for bundling payments and accountable care organizations, which reward doctors for teamwork and patient outcomes.

Mayo Clinic President and CEO Denis Cortese has advocated an overall strategy to guide reform efforts. He argued that the U.S. has an opportunity to redesign its healthcare system and that there is a wide consensus that reform is necessary. He articulated four "pillars" of such a strategy:

- Focus on value, which he defined as the ratio of quality of service provided relative to cost;

- Pay for and align incentives with value;

- Cover everyone;

- Establish mechanisms for improving the healthcare service delivery system over the long-term, which is the primary means through which value would be improved.

Writing in The New Yorker, surgeon Atul Gawande further distinguished between the delivery system, which refers to how medical services are provided to patients, and the payment system, which refers to how payments for services are processed. He argued that reform of the delivery system is critical to getting costs under control, but that payment system reform (e.g., whether the government or private insurers process payments) is considerably less important yet gathers a disproportionate share of attention. Gawande argued that dramatic improvements and savings in the delivery system will take "at least a decade." He recommended changes that address the overutilization of healthcare; the refocusing of incentives on value rather than profits; and comparative analysis of the cost of treatment across various healthcare providers to identify best practices. He argued this would be an iterative, empirical process and should be administered by a "national institute for healthcare delivery" to analyze and communicate improvement opportunities.

Use of comparative effectiveness research

Several treatment alternatives may be available for a given medical condition, with significantly different costs yet no statistical difference in outcome. Such scenarios offer the opportunity to maintain or improve the quality of care, while significantly reducing costs, through comparative effectiveness research. Writing in the New York Times, David Leonhardt described how the cost of treating the most common form of early-stage, slow-growing prostate cancer ranges from an average of $2,400 (watchful waiting to see if the condition deteriorates) to as high as $100,000 (radiation beam therapy):

According to economist Peter A. Diamond and research cited by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the cost of healthcare per person in the U.S. also varies significantly by geography and medical center, with little or no statistical difference in outcome.

Comparative effectiveness research has shown that significant cost reductions are possible. OMB Director Peter Orszag stated: "Nearly thirty percent of Medicare's costs could be saved without negatively affecting health outcomes if spending in high- and medium-cost areas could be reduced to the level of low-cost areas."

Reform of doctor's incentives

Critics have argued that the healthcare system has several incentives that drive costly behavior. Two of these include:

- Doctors are typically paid for services provided rather than with a salary. This payment system (which is often referred to as "fee-for-service") provides a financial incentive to increase the costs of treatment provided.

- Patients that are fully insured have no financial incentive to minimize the cost when choosing from among alternatives. The overall effect is to increase insurance premiums for all.

Insurance reforms

The debate has involved certain insurance industry practices such as the placing of caps on coverage, the high level of co-pays even for essential services such as preventative procedures, the refusal of many insurers to cover pre-existing conditions or adding premium loading for these conditions, and practices which some people regard as egregious such as the additional loading of premiums for women, the regarding of having previously been assaulted by a partner as having a pre-existing condition, and even the cancellation of insurance policies on very flimsy grounds when a claimant who had paid in many premiums presents with a potentially expensive medical condition.

Various legislative proposals under serious consideration propose fining larger employers who do not provide a minimum standard of healthcare insurance and mandating that people purchase private healthcare insurance. This is the first time that the Federal government has mandated people to buy insurance, although nearly all states in the union currently mandate the purchase of auto insurance. The legislation also taxes certain very high payout insurance policies (so-called "Cadillac policies") to help finance subsidies for poorer citizens. These will be offered on a sliding scale to people earning less than four times the federal poverty level to enable them to buy health insurance if they are not otherwise covered by their employer.

The issue of concentration of power by the insurance industry has also been a focus of debate as in many states very few large insurers dominate the market. Legislation which would provide a choice of a not-for-profit insurer modeled on Medicare but funded by insurance premiums has been a contentious issue. Much debate surrounded Medicare Advantage and the profits of insurers selling it.

Certain proposals include a choice of a not-for-profit insurer modeled on Medicare (sometimes called the "government option"). Democratic legislators have largely supported the proposed reform efforts, while Republicans have criticized the government option or expanded regulation of healthcare.

The GAO reported in 2002 (using 2000 data) that: "The median number of licensed carriers in the small group market per state was 28, with a range from 4 in Hawaii to 77 in Indiana. The median market share of the largest carrier was about 33 percent, with a range from about 14 percent in Texas to about 89 percent in North Dakota."

The GAO reported in 2008 (using 2007 data for the most part) that: "The median number of licensed carriers in the small group market per state was 27. The median market share of the largest carrier in the small group market was about 47%, with a range from about 21% in Arizona to about 96% in Alabama. In 31 of the 39 states supplying market share information, the top carrier had a market share of a third or more. The five largest carriers in the small group market, when combined, represented three quarters or more of the market in 34 of the 39 states supplying this information, and they represented 90% or more in 23 of these states....the median market share of all the BCBS carriers in 38 states reporting this information in 2008 was about 51%, compared to the 44% reported in 2005 and the 34% reported in 2002 for the 34 states supplying information in each of these years."

Tax reform

The Congressional Budget Office has also described how the tax treatment of insurance premiums may affect behavior:

One factor perpetuating inefficiencies in health care is a lack of clarity regarding the cost of health insurance and who bears that cost, especially employment-based health insurance. Employers’ payments for employment-based health insurance and nearly all payments by employees for that insurance are excluded from individual income and payroll taxes. Although both theory and evidence suggest that workers ultimately finance their employment-based insurance through lower take-home pay, the cost is not evident to many workers.... If transparency increases and workers see how much their income is being reduced for employers’ contributions and what those contributions are paying for, there might be a broader change in cost-consciousness that shifts demand.

In November 2009, The Economist estimated that taxing employer-provided health insurance (which is presently exempt from tax) would add $215 billion per year to federal tax revenue during the 2013–2014 periods. Peter Singer wrote in The New York Times that the current exclusion of insurance premiums from compensation represents a $200 billion subsidy for the private insurance industry and that it would likely not exist without it. In other words, taxpayers might be more inclined to change behavior or the system itself if they were paying $200 billion more in taxes each year related to health insurance. To put this amount in perspective, the federal government collected $1,146 billion in income taxes in 2008, so $200 billion represents a 17.5% increase in the effective tax rate.

Independent advisory panels

President Obama has proposed an "Independent Medicare Advisory Panel" (IMAC) to make recommendations on Medicare reimbursement policy and other reforms. Comparative effectiveness research would be one of many tools used by the IMAC. The IMAC concept was endorsed in a letter from several prominent healthcare policy experts, as summarized by OMB Director Peter Orszag:

Their support of the IMAC proposal underscores what most serious health analysts have recognized for some time: that moving toward a health system emphasizing quality rather than quantity will require continual effort, and that a key objective of legislation should be to put in place structures (like the IMAC) that facilitate such change over time. And ultimately, without a structure in place to help contain costs over the long term as the health market evolves, nothing else we do in fiscal policy will matter much, because eventually rising health care costs will overwhelm the federal budget.

Both Mayo Clinic CEO Dr. Denis Cortese and surgeon/author Atul Gawande have argued that such panel(s) will be critical to reform of the delivery system and improving value. Washington Post columnist David Ignatius has also recommended that President Obama engage someone like Cortese to have a more active role in driving reform efforts.

Lowering obesity

Preventing obesity and overweight conditions presents a significant opportunity to reduce costs. The Centers for Disease Control reported that approximately 9% of healthcare costs in 1998 were attributable to overweight and obesity, or as much as $93 billion in 2002 dollars. Nearly half of these costs were paid for by the government via Medicare or Medicaid. However, by 2008 the CDC estimated these costs had nearly doubled to $147 billion. The CDC identified a series of expensive conditions more likely to occur due to obesity. The CDC released a series of strategies to prevent obesity and overweight, including: making healthy foods and beverages more available; supporting healthy food choices; encouraging kids to be more active; and creating safe communities to support physical activity. An estimated 26% of U.S. adults in 2007 were obese, versus 24% in 2005. State obesity rates ranged from 18% to 30%. Obesity rates were roughly equal among men and women. Some have proposed a so-called "fat tax" to provide incentives for healthier behavior, either by levying the tax on products (such as soft drinks) that are thought to contribute to obesity, or to individuals based on body measures, as is done in Japan.

Rationing of care

Healthcare rationing may refer to the restriction of medical care service delivery based on any number of objective or subjective criteria. Republican Newt Gingrich argued that the reform plans supported by President Obama expand the control of government over healthcare decisions, which he referred to as a type of healthcare rationing. President Obama has argued that U.S. healthcare is already rationed, based on income, type of employment, and medical pre-existing conditions, with nearly 46 million uninsured. He argued that millions of Americans are denied coverage or face higher premiums as a result of medical pre-existing conditions.

Peter Singer wrote in the New York Times in July 2009 that healthcare is rationed in the United States and argued for improved rationing processes:

Health care is a scarce resource, and all scarce resources are rationed in one way or another. In the United States, most healthcare is privately financed, and so most rationing is by price: you get what you, or your employer, can afford to insure you for...Rationing healthcare means getting value for the billions we are spending by setting limits on which treatments should be paid for from the public purse. If we ration we won’t be writing blank checks to pharmaceutical companies for their patented drugs, nor paying for whatever procedures doctors choose to recommend. When public funds subsidize healthcare or provide it directly, it is crazy not to try to get value for money. The debate over healthcare reform in the United States should start from the premise that some form of healthcare rationing is both inescapable and desirable. Then we can ask, What is the best way to do it?"

According to PolitiFact, private health insurance companies already ration healthcare by income, by denying health insurance to those with pre-existing conditions and by caps on health insurance payments. Rationing exists now, and will continue to exist with or without healthcare reform. David Leonhardt also wrote in the New York Times in June 2009 that rationing is a part of economic reality: "The choice isn’t between rationing and not rationing. It’s between rationing well and rationing badly. Given that the United States devotes far more of its economy to healthcare than other rich countries, and gets worse results by many measures, it’s hard to argue that we are now rationing very rationally."

Palin's death panel remarks were based on the ideas of Betsy McCaughey. During 2009, former Alaska Governor Sarah Palin wrote against alleged rationing, referring to what by her interpretation was a "downright evil" "death panel" in current reform legislation known as H.R. 3200 Section 1233. However, Palin supported similar end of life discussion and advance directives for patients in 2008. Defenders of the plan indicated that the proposed legislation H.R. 3200 would allow Medicare for the first time to cover patient-doctor consultations about end-of-life planning, including discussions about drawing up a living will or planning hospice treatment. Patients could seek out such advice on their own, but would not be required to. The provision would limit Medicare coverage to one consultation every five years. Rep. Earl Blumenauer, D-Ore., who sponsored the H.R. 3200 end of life counseling provision, said the measure would block funds for counseling that presents suicide or assisted suicide as an option, and called references to death panels or euthanasia "mind-numbing". Republican Senator Johnny Isakson, who co-sponsored a 2007 end-of-life counseling provision, called the euthanasia claim "nuts". Analysts who examined the end-of-life provision Palin cited agree that Palin's claim is incorrect. According to TIME and ABC, Palin and Betsy McCaughey made false euthanasia claims.

The federal requirement that hospitals help patients with things like living wills began when Republican George H. W. Bush was President. Section 1233 merely allows doctors to be paid for their time. However, an NBC poll indicates that as of August, 2009, 45% of Americans believed in the death panel story.

Slate columnist Christopher Beam used the term "deathers" to refer to those who believed rationing and euthanasia would become likely for senior citizens. The Rachel Maddow Show aired a program called "Obama and the Deathers" in which Maddow discussed conspiracy theories that included "a secret plot to kill old people." Daily Kos and other web sites had used the term for about a week before Hari Sevugan, national spokesman for the Democratic National Committee, sent out an email with the subject line "Murkowski: Deathers 'Lying' 'Inciting Fear.'" The message included an article about a town hall statement by Senator Lisa Murkowski, a Republican from Alaska, that no version of healthcare reform included "death panels".

Sevugan explained the term "deathers" to Patricia Murphy, who used to write a Politics Daily column called "The Capitolist":

By "deather," I mean an opponent of change who is knowingly spreading false information regarding the existence of an alleged "death panel" in health insurance reform plans despite the fact the claim has been repeatedly and unequivocally debunked by independent fact-checking organizations. Like "birthers", "deathers" are shamefully lying and trafficking in scurrilous rumors to incite fear and achieve their stated political objective of derailing the president of the United States.

Others, such as former Republican Secretary of Commerce Peter G. Peterson, have indicated that some form of rationing is inevitable and desirable considering the state of U.S. finances and the trillions of dollars of unfunded Medicare liabilities. He estimated that 25–33% of healthcare services are provided to those in the last months or year of life and advocated restrictions in cases where quality of life cannot be improved. He also recommended that a budget be established for government healthcare expenses, through establishing spending caps and pay-as-you-go rules that require tax increases for any incremental spending. He has indicated that a combination of tax increases and spending cuts will be required. All of these issues would be addressed under the aegis of a fiscal reform commission.

Medical malpractice costs and limits on redress (tort)

Critics have argued that medical malpractice costs are significant and should be addressed via tort reform. At the same time, a Hearst Newspapers investigation concluded that up to 200,000 people per year die from medical errors and infections in the United States. None of the three major bills under consideration lower recoverable damages in tort suits. Medical malpractice, such as doctor errors resulting in harm to patients, has several direct and indirect costs:

- jury awards to injured;

- workers' compensation;

- reduced worker productivity as a result of injury;

- pain and suffering of the injured;

How much these costs are is a matter of debate. Some have argued that malpractice lawsuits are a major driver of medical costs. However, the direct cost of malpractice suits amounts to only about 0.5% of all healthcare spending, and a 2006 Harvard study showed that over 90% of the malpractice suits examined contained evidence of injury to the patient and that frivolous suits were generally readily dismissed by the courts. A 2005 study estimated the cost around 0.2%, and in 2009 insurer WellPoint Inc. said "liability wasn’t driving premiums." Counting both direct and indirect costs, other studies estimate the total cost of malpractice "is linked to" between 5% and 10% of total U.S. medical costs. A 2004 report by the Congressional Budget Office put medical malpractice costs at 2% of U.S. health spending and "even significant reductions" would do little to reduce the growth of health care expenses.

Conservative columnist Charles Krauthammer argued that between $60–200 billion per year could be saved through tort reform. Physician and former Democratic National Committee Chairman Howard Dean explained why tort reform is not part of the bills under consideration: "When you go to pass a really enormous bill like that, the more stuff you put it in it, the more enemies you make, right?...And the reason tort reform is not on the bill is because the people who wrote it did not want to take on the trial lawyers in addition to everybody else they were taking on. That is the plain and simple truth."

However, even successful tort reform might not lead to lower aggregate liability: for example, medical commentators have argued that the current contingent fee system skews litigation towards high-value cases while ignoring meritorious small cases; aligning litigation more closely with merit might thus increase the number of small awards, offsetting any reduction in large awards. A New York study found that only 1.5% of hospital negligence led to claims; moreover, the CBO observed that "health care providers are generally not exposed to the financial cost of their own malpractice risk because they carry liability insurance, and the premiums for that insurance do not reflect the records or practice styles of individual providers but more-general factors such as location and medical specialty." Given that total liability is small relative to the amount doctors pay in malpractice insurance premiums, alternative mechanisms have been proposed to reform malpractice insurance.

Addressing the shortage of doctors, nurses and hospital capacity

The U.S. is facing shortages of doctors and nurses that are projected to grow worse as America ages, which may drive up the price of these services. Writing in The Washington Post, cardiologist Arthur Feldman cited various studies that indicate the U.S. is facing a "critical" shortage of doctors, including an estimated 1,300 general surgeons by 2010.

The American Academy of Family Physicians predicts a shortage of 40,000 primary care doctors (including family practice, internal medicine, pediatrics and obstetrics/gynecology) by 2020. The number of medical students choosing the primary care specialty has dropped by 52% since 1997. Currently, only 2% of medical school graduates choose primary care as a career. An amendment to the Senate health bill includes $2 billion in funds over 10 years to create 2,000 new residency training slots geared toward primary care medicine and general surgery. Writing in Forbes, a physician argued that this is a "tiny band-aid at best," advocating full loan repayments and guaranteed positions upon graduation.

The U.S. had 2.4 doctors per 1,000 people in 2002, ranking 52nd. Germany and France had approximately 3.4 and ranked in the top 25. The OECD average in 2008 was 3.1 doctors per 1,000 people, while the U.S. had 2.4.

The American Association of Colleges of Nurses cited studies estimating that a shortage of registered nurses would reach 230,000 by 2025 as America ages, with over 135,000 open positions during 2007. An additional 30% more nurses would have to graduate annually to keep up with demand. A study by Price Waterhouse advanced several strategies for addressing the nursing shortage, including developing more public-private partnerships, federal and state-level grants for nursing students and educators, creating healthy work environments, using technology as a training tool, and designing more flexible roles for advanced practice nurses given their increased use as primary care providers.

In addition, the U.S. also does not measure favorably vs. OECD countries in terms of acute care hospital beds. Only four OECD countries have fewer acute care hospital beds per capita than the U.S, which has 2.7 per 1,000 population versus an OECD average of 3.8. Japan has 8.2 acute care beds per 1,000 population.

Addressing Medicare fraud

The Office of Management and Budget reported that $54 billion in "improper payments" were made to Medicare ($24B), Medicaid ($18B) and Medicaid Advantage ($12B) during FY 2009. This was 9.4% of the $573 billion spent in these categories. The Government Accountability Office lists Medicare as a "high-risk" government program due to its vulnerability to improper payments. Fewer than 5% of Medicare claims are audited. Medicare fraud accounts for an estimated $60 billion in Medicare payments each year, and "has become one of, if not the most profitable, crimes in America." Criminals set up phony companies, then invoice Medicare for fraudulent services provided to valid Medicare patients who never receive the services. These costs appear on the Medicare statements provided to Medicare card holders. The program pays out over $430 billion per year via over 1 billion claims, making enforcement challenging. Its enforcement budget is "extremely limited" according to one Medicare official. U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder said in an interview: "Clearly more auditing needs to be done and it needs to be done in real time." The Obama administration provided Medicare with an additional $200 million to fight fraud as part of its stimulus package, and billions of dollars to computerize medical records and upgrade networks, which should assist Medicare in identifying fraudulent claims.

Single-payer payment system

In a single payer system the government or a government regulated non-profit agency channels health care payments to collect premiums and settle the bills of medical providers, instead of for-profit insurance companies. Many countries use single-payer systems to cover all their citizens.

The over 1,300 U.S. health insurance companies have different forms and processes for billing and reimbursement, requiring high costs on the part of service providers (mainly doctors and hospitals) to process payments. For example, the Cleveland Clinic, considered a low-cost, best-practices hospital system, has 1,400 billing clerks to support 2,000 doctors. Further, the insurance companies have their own overhead functions and profit margins, much of which could be eliminated with a single payer system. Economist Paul Krugman estimated in 2005 that converting from the current private insurance system to a single-payer system would save $200 billion per year, primarily via insurance company overhead. One advocacy group estimated savings as high as $400 billion annually for 2009 and beyond.

The U.S. system is often compared with that of its northern neighbor, Canada. Canada's system is largely publicly funded. In 2006, Americans spent an estimated US$6,714 per capita on health care, while Canadians spent US$3,678. This amounted to 15% percent of U.S. GDP in that year, while Canada spent 10%. A study by Harvard Medical School and the Canadian Institute for Health Information determined that some 31% of U.S. health care dollars (more than $1,000 per person per year) went to health care administrative costs.

Advocates argue that shifting the U.S. to a single-payer health care system would provide universal coverage, give patients free choice of providers and hospitals, and guarantee comprehensive coverage and equal access for all medically necessary procedures, without increasing overall spending. Shifting to a single-payer system would also eliminate oversight by managed care reviewers, removing a potential impediment to the doctor-patient relationship. Opponents argue that switching to a single-payer system would create more problems and setbacks. The American Medical Association argued that the single-payer system would be burdened by longer wait times, would be inefficient when it comes to medical innovation and facility maintenance, and a large bureaucracy could "cause a decline in the authority of patients and their physicians over clinical decision-making."

Although studies indicate Democrats tend to be more supportive of a single-payer system than Republicans, none of the reform bills debated in the U.S. Congress when the Democrats had a majority from 2007–2010, included proposals to implement a single payer health care system. Advocates argue that the largest obstacle to single-payer, universal system in the U.S. is a lack of political will.

Privatize Medicare with a voucher system

Rep. Paul Ryan (R) has proposed the Roadmap for America's Future, which is a series of budgetary reforms. His January 2010 version of the plan includes the transition of Medicare to a voucher system, meaning individuals would receive a voucher which could be used to purchase health insurance in the private market. This would not affect those near retirement or currently enrolled. A series of graphs and charts summarizing the impact of the plan are included. Economists have both praised and criticized particular features of the plan. The CBO also partially scored the bill.

Congressional Proposals for Health Care Reform

On November 7, 2009, the House passed their version of a health insurance reform bill, the Affordable Health Care for America Act, 220–215, but this did not become law.

On December 24, 2009, the Senate passed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. President Obama signed this into law in March 2010.

Republicans continue to claim that they had a workable bill to extend coverage to all Americans and not cost the taxpayer anything, though nothing has been publicly presented to back the claim. The Empowering Patients First Act which was proposed as a replacing amendment to the Senate Bill during the bill mark-up. However, this alternative bill was rejected by the Senate Finance Committee. The Congressional Budget Office said that it would not reduce the percentage of working age people who do not have insurance over the next 10 years, and that it estimated it would encourage health insurers to reduce rather than increase insurance coverage as it would remove mandated coverage rules that currently apply in some states. This bill would have given the insurance industry greater access to government funds through new insurance subsidies. It did not have any taxation provisions and though it would reduce the deficit over 10 years by $18 billion, this was a considerably smaller deficit reduction than either the House or the Senate bills.

|

|

H.R. 3962, Affordable Health Care for America Act, "House Bill" | H.R. 3590, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, "Senate Bill" |

|---|---|---|

| Financing | Places a 5.4% surtax on incomes over $500,000 for individuals and $1,000,000 for families. | Increases the Medicare payroll tax from 1.45% to 2.35% on incomes over $200,000 for individuals and $250,000 for families. |

| Abortion | Insurance companies that accept federal subsidies will not be allowed to cover abortion. | Insurance companies that participate in the newly created exchanges will be permitted to include abortion coverage, but a separate check must be written to the participating insurance company. Each state will have the option to prevent federal money from funding abortions in their insurance exchanges. |

| Public Option | Yes. | No. Instead, the federal government will mandate that newly created State insurance exchanges include at least two national plans that are created by the Office of Personnel Management. Of these two national plans, at least one will have to be a private non-profit plan. |

| Insurance Exchanges | A single national insurance exchange will be created to house private insurance plans as well as a public option. Individual states could run their own exchanges under federal guidelines. | Each state will create its own insurance exchange under federal guidelines. |

| Medicaid Eligibility | Expanded to 150% of the federal poverty level | Expanded to 133% of the federal poverty level |

| Illegal Immigrants | They are allowed to participate in the insurance exchanges, but cannot receive federal subsidies. | They cannot participate in the exchange or receive subsidies. |

| CBO Cost Estimate | $1,050 billion dollars over 10 years. Deficit would be reduced a total of $138 billion 2010–2019 after tax receipts and cost reductions. | $871 billion over 10 years. Deficit would be reduced a total of $132 billion 2010–2019 after tax receipts and cost reductions. |

| Takes effect | 2013 | 2014 |

Similarities between the House and Senate Bills

The two bills are similar in a number of ways. In particular, both bills:

- Mandate minimum health insurance benefits for most Americans

- Remove insurer set annual and lifetime caps on coverage and limit co-pay amounts

- Remove co-pays on certain services such as health screenings and some vaccinations

- Impose a new excise tax on medical devices and drugs, including vaccines (the federal government began taxing vaccines in 1987).

- Establish health insurance exchanges making easier price and coverage comparisons and purchasing for people and small businesses buying health care coverage

- Prevent insurers selling in the exchange insurance policies that do not meet minimum coverage standards

- Prevent insurers from denying coverage to people with pre-existing health conditions

- Prevent sex discrimination by insurers (especially the current discrimination against women) in setting premiums

- Limit age discrimination by insurers when setting policy premiums

- Restrict the ability of insurers to rescind policies they have been collecting premiums on

- Require insurers to cover adult children up to their mid twenties as part of family coverage

- Expand Medicaid eligibility up the income ladder (to 133% of the poverty line in the Senate bill and 150% in the House bill)

- Offer tax credits to certain small businesses (under 25 workers) who provide employees with health insurance

- Impose a penalty on employers who do not offer health insurance to their workers

- Impose a penalty on individuals who do not have health insurance (except American Indians (currently covered by the Indian Health Service), people with religious objections and people who can show financial hardship)

- Provide health insurance assistance subsidies for those earning up to 400% of the federal poverty level that must buy insurance for themselves

- Offer a new voluntary long-term care insurance program

- Pay for new spending, in part, through cutting over-generous funding (under existing law) given to private insurers that sell privatised health care plans to seniors, slowing the growth of Medicare provider payments, reducing Medicare and Medicaid drug prices, cutting other Medicare and Medicaid spending through better reward structures, and raising taxes on very generous health care packages (typically offered to senior executives) and penalties on larger firms not providing their employees with health care coverage and certain persons who do not buy health insurance.

- Impose a $2,500 limit on contributions to a flexible spending account (FSAs), pre-tax health benefits, to pay for health care reform costs.

Differences in the House and Senate Bills

The biggest difference between the bills, currently, is in how they are financed. In addition to the items listed in the above bullet point, the House relies mainly on a surtax on income above $500,000 ($1 million for families). The Senate, meanwhile, relies largely on an "excise tax" for high cost 'Cadillac' insurance plans, as well as an increase in the Medicare payroll tax for high earners.

Most economists believe the excise tax to be best of the three revenue raisers above, since (due to health care cost growth) it would grow fast enough to more than keep up with new coverage costs, and it would help to put downward pressure on overall health care cost growth. In contrast, the House bill's insurance mandate has been described as "an economic assault on the young" by, for example, Robert J. Samuelson for The Washington Post.

Unlike the House bill, the Senate bill would also include a Medicare Commission which could modify Medicare payments in order to keep down cost growth.

Services marketed as preventive care are a subject of continuing debate. Years of study have shown that most common services provide no benefit to patients. The House and Senate bills would mandate the purchase of policies that pay 100% of the cost of certain services, with no co-pay; when the Senate bill was amended to mandate paying for tests that a federal panel and U.S. News & World Report said "do more harm than good," The New York Times wrote, "This sorry episode does not bode well for reform efforts to rein in spending on other procedures based on sound scientific evidence of their potential benefits and risks for patients."

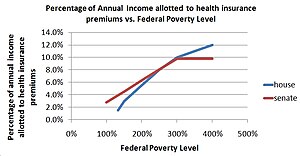

Differences in how each chamber determines subsidies

How each bill determines subsidies also differs. Each bill subsidizes the cost of the premium and the out-of-pocket costs but are more or less generous based on the relationship of the family's income to the federal poverty level.

The amount of the subsidy given to a family to cover the cost of a premium is calculated using a formula that includes the family's income relative to the federal poverty level. The federal poverty level is related to a determined percentage that defines how much of that family's income can be put towards a health insurance premium. For instance, under the House Bill, a family at 200% of the federal poverty level will spend no more than 5.5% of its annual income on health insurance premiums. Under the Senate Bill, the same family would spend no more than 6.3% of its annual income on health insurance premiums. The difference between the family's maximum contribution to health insurance premiums and the cost of the health insurance premium is paid for by the federal government. To understand how each bill can affect different poverty levels and incomes, see the Kaiser Family Foundation's subsidy calculator

Subsidies Under House Bill

The House plan subsidizes the cost of the plan and out-of-pocket expenses. The cost of the plan is subsidized according to the family's poverty level, decreasing the subsidy as the poverty level approaches 400%. The out-of-pocket expenses are also subsidized according to the poverty level at the following rates. The out-of-pocket expenses are subsidized initially and are not allowed to exceed a particular amount that will rise with the premiums for basic insurance.

| For those making between | This much of the out-of-pocket expenses are covered | And no more than this much will be spent by the individual (family) on out-of-pocket expenses. |

|---|---|---|

| up to 150% of the FPL | 97% | $500 ($1,000) |

| 150% and 200% of the FPL | 93% | $1,000 ($2,000) |

| 200% and 250% of the FPL | 85% | $2,000 ($4,000) |

| 250% and 300% of the FPL | 78% | $4,000 ($8,000) |

| 300% and 350% of the FPL | 72% | $4,500 ($9,000) |

| 350% and 400% of the FPL | 70% | $5,000 ($10,000) |

Subsidies Under Senate Bill

The Senate plan subsidizes the cost of the plan and out-of-pocket expenses. The cost of the plan is subsidized according to the family's poverty level, decreasing the subsidy as the poverty level approaches 400%. The out-of-pocket expenses are also subsidized according to the poverty level at the following rates. The out-of-pocket expenses are subsidized initially and are not allowed to exceed a particular amount that will rise with the premiums for basic insurance.

| For those making between | This much of the out of the out-of-pocket expenses are covered |

|---|---|

| up to 200% of the FPL | 66% |

| 200% and 300% of the FPL | 50% |

| 300% and 400% of the FPL | 33% |

The Senate Bill also seeks to reduce out-of-pocket costs by setting guidelines for how much of the health costs can be shifted to a family within 200% of the poverty line. A family within 150% of the FPL cannot have more than 10% of their health costs incurred as out-of-pocket expenses. A family between 150% and 200% of the FPL cannot have more than 20% of their health costs incurred as out-of-pocket expenses.

The House and Senate bill would differ, somewhat, in their overall impact. The Senate bill would cover an additional 31 million people, at a federal budget cost of nearly $850 billion (not counting unfunded mandates) over ten years, reduce the ten-year deficit by $130 billion, and reduce the deficit in the second decade by around 0.25% of GDP. The House bill, meanwhile, would cover an additional 36 million people, cost roughly $1050 billion in coverage provisions, reduce the ten-year deficit by $138 billion, and slightly reduce the deficit in the second decade.

Commentary on the cost analysis

It is worth noting that both bills rely on a number of "gimmicks" to get their favorable deficit reduction numbers. For example, both institute a public long-term care insurance known as the CLASS Act – because this insurance has a 5-year vesting period, it will appear to raise revenue in the first decade, even though all the money will need to be paid back. If the CLASS Act is subtracted from the bills, the Senate bill would reduce the deficit by $57 billion over ten years, and the House by $37 billion. In addition to the CLASS Act, neither bill accounts for the costs of updating Medicare physician payments, even though the House did so on a deficit-financed basis shortly after passing their health care bill.

The Senate bill also begins most provisions a year later than the House bill in order to make costs seem smaller:

Surgeon Atul Gawande wrote in The New Yorker that the Senate and House bills passed contain a variety of pilot programs that may have a significant impact on cost and quality over the long-run, although these have not been factored into CBO cost estimates. He stated these pilot programs cover nearly every idea healthcare experts advocate, except malpractice/tort reform. He argued that a trial and error strategy, combined with industry and government partnership, is how the U.S. overcame a similar challenge in the agriculture industry in the early 20th century.

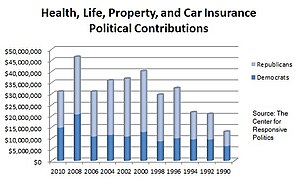

Lobbying

The health and insurance sectors gave nearly $170 million to House and Senate members in 2007 and 2008, with 54% going to Democrats, according to data compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics. The shift in parties was even more pronounced during the first three months of 2009, when Democrats collected 60% of the $5.4 million donated by health care companies and their employees, the data show. Lawmakers that chair key committees have been leading recipients, some of whom received over $1.0 million in contributions.

Matt Taibbi wrote in Rolling Stone that President Obama and key senators who have advocated single-payer systems in the past are unwilling to face the insurance companies and their powerful lobbying efforts. Key politicians on the Senate Finance Committee involved in crafting legislation have received over $2 million in campaign contributions from the healthcare industry. Several of the firms invited to testify at the hearings sent lobbyists that had formerly worked for Senator Max Baucus, the chair of the committee. Mr. Baucus stated in February 2009 that: "There may come a time when we can push for single-payer. At this time, it's not going to get to first base in Congress."

George McGovern wrote that significant campaign funds were given to the chairman and ranking minority member of the Senate Finance Committee, which has jurisdiction over health care legislation: "Chairman Max Baucus of Montana, a Democrat, and his political action committee have received nearly $4 million from the health-care lobby since 2003. The ranking Republican, Charles Grassley of Iowa, has received more than $2 million. It's a mistake for one politician to judge the personal motives of another. But Sens. Baucus and Grassley are firm opponents of the single-payer system, as are other highly placed members of Congress who have been generously rewarded by the insurance lobby."

Debate about political organizing methods

Much of the coverage of the debate has involved how the different sides are competing to express their views, rather than the specific reform proposals. The health care reform debate in the United States has been influenced by the Tea Party protest phenomenon, with reporters and politicians spending time reacting to it. Supporters of a greater government role in healthcare, such as former insurance PR executive Wendell Potter of the Center for Media and Democracy- whose funding comes from groups such as the Tides Foundation- argue that the hyperbole generated by this phenomenon is a form of corporate astroturfing, which he says that he used to write for CIGNA. Opponents of more government involvement, such as Phil Kerpen of Americans for Prosperity- whose funding comes mainly from the Koch Industries corporation-counter-argue that those corporations oppose a public-plan, but some try to push for government actions that will unfairly benefit them, such as forcing private companies to buy health insurance for their employees. Journalist Ben Smith has referred to mid-2009 as "The Summer of Astroturf" given the organizing and co-ordinating efforts made by various groups on both pro- and anti-reform sides.

Arguments concerning health care reform

Liberal arguments

Some have argued that health care is a fundamental human right. Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states: "Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services." Similarly, Franklin D. Roosevelt advocated a right to medical care in his 1944 proposal for a Second Bill of Rights.

Liberals were the primary advocates of both Social Security and Medicare, which are often targeted as significant expansions of government that has overwhelming satisfaction among beneficiaries. President Obama argued during a September 2009 joint session of Congress that the government has a moral responsibility to ensure quality healthcare is available to all citizens. He also referred to a letter from the late Senator Ted Kennedy.

Economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman has argued that Republican and conservative strategies in opposing healthcare are based on spite: "At this point, the guiding principle of one of our nation’s two great political parties is spite pure and simple. If Republicans think something might be good for the president, they’re against it – whether or not it’s good for America." He argued that Republican opposition to Medicare savings proposed by the President is "utterly at odds both with the party’s traditions and with what conservatives claim to believe. Think about just how bizarre it is for Republicans to position themselves as the defenders of unrestricted Medicare spending. First of all, the modern G.O.P. considers itself the party of Ronald Reagan – and Reagan was a fierce opponent of Medicare’s creation, warning that it would destroy American freedom. (Honest.) In the 1990s, Newt Gingrich tried to force drastic cuts in Medicare financing. And in recent years, Republicans have repeatedly decried the growth in entitlement spending – growth that is largely driven by rising health care costs."

Conservative and libertarian arguments

Conservatives and libertarians have historically argued for a lesser role of government in healthcare.

For example, Conservative GOP columnist Bill Kristol advocated several free-market reforms instead of the Clinton plan during the 1993–1994 period. Investigative reporter and columnist John Stossel has remarked that "Insurance invites waste. That's a reason health care costs so much, and is often so consumer-unfriendly. In the few areas where there are free markets in health care – such as cosmetic medicine and Lasik eye surgery – customer service is great, and prices continue to drop." Republican Senator and medical doctor Tom Coburn has stated that the healthcare system in Switzerland should serve as a model for U.S. reform. He wrote for New York Sun that reform should involve a market-based method transferring health care tax benefits to individuals rather than employers as well as giving individuals extra tax credits to afford more coverage.

Some critics of the bills passed in 2009 call them a "government take over of health care." FactCheck called the phrase an unjustified "mantra." (Factcheck has also criticized a number of other assertions made during 2009 by advocates on both sides of the debate). CBS News described it as a myth "mixed in with some real causes for concern." President Obama disputes the notion of a government takeover and says he no more wants government bureaucrats meddling than he wants insurance company bureaucrats doing so. Other sources contend the bills do amount to either a government takeover or a corporate takeover, or both. This debate occurs in the context of a "revolution...transforming how medical care is delivered:" from 2002 to 2008, the percentage of medical practices owned by doctors fell from more than 70% to below 50%; in contrast to the traditional practice in which most doctors cared for patients in small, privately owned clinics, by 2008 most doctors had become employees of hospitals, nearly all of which are owned by corporations or government.

Republicans also argue the proposed excise tax on medical devices and drugs would increase the tax burden on vaccine makers.

Some conservatives argue that forcing people to buy private insurance is unconstitutional; legislators in 38 states have introduced bills opposing the new law, and 18 states have filed suit in federal court challenging the unfunded mandates on individuals and states.

Senator Judd Gregg (R) said in an interview regarding the passage of healthcare reform: "Well, in my judgment we’re moving down a path towards... Europeanization of our nation. And our great uniqueness, what surrounds American exceptionalism, what really drives it is that entrepreneurial individualistic spirit which goes out and takes a risk when nobody else is willing to do it or comes up with an idea that nobody else comes up with and that all gets dampened down the larger and more intrusive government becomes, especially if you follow a European model."