From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Anger, also known as wrath or rage, is an intense emotional state involving a strong uncomfortable and non-cooperative response to a perceived provocation, hurt or threat.

A person experiencing anger will often experience physical

effects, such as increased heart rate, elevated blood pressure, and

increased levels of adrenaline and noradrenaline. Some view anger as an emotion which triggers part of the fight or flight response.

Anger becomes the predominant feeling behaviorally, cognitively, and

physiologically when a person makes the conscious choice to take action

to immediately stop the threatening behavior of another outside force. The English term originally comes from the term anger of Old Norse language.

Anger can have many physical and mental consequences. The external expression of anger can be found in facial expressions, body language, physiological responses, and at times public acts of aggression. Facial expressions can range from inward angling of the eyebrows to a full frown.

While most of those who experience anger explain its arousal as a

result of "what has happened to them", psychologists point out that an

angry person can very well be mistaken because anger causes a loss in self-monitoring capacity and objective observability.

Modern psychologists view anger as a normal, natural, and mature

emotion experienced by virtually all humans at times, and as something

that has functional value for survival. Uncontrolled anger can, however,

negatively affect personal or social well-being

and impact negatively on those around them. While many philosophers and

writers have warned against the spontaneous and uncontrolled fits of

anger, there has been disagreement over the intrinsic value of anger.

The issue of dealing with anger has been written about since the times

of the earliest philosophers, but modern psychologists, in contrast to

earlier writers, have also pointed out the possible harmful effects of

suppressing anger.

Psychology and sociology

Three types of anger are recognized by psychologists:

- Hasty and sudden anger is connected to the impulse for

self-preservation. It is shared by human and other animals, and it

occurs when the animal is tormented or trapped. This form of anger is

episodic.

- Settled and deliberate anger is a reaction to perceived deliberate harm or unfair treatment by others. This form of anger is episodic.

- Dispositional anger is related more to character traits than

to instincts or cognitions. Irritability, sullenness, and churlishness

are examples of the last form of anger.

Anger can potentially mobilize psychological resources and boost

determination toward correction of wrong behaviors, promotion of social justice,

communication of negative sentiment, and redress of grievances. It can

also facilitate patience. In contrast, anger can be destructive when it

does not find its appropriate outlet in expression. Anger, in its strong

form, impairs one's ability to process information and to exert cognitive control over one's behavior. An angry person may lose their objectivity, empathy, prudence or thoughtfulness and may cause harm to themselves or others. There is a sharp distinction between anger and aggression

(verbal or physical, direct or indirect) even though they mutually

influence each other. While anger can activate aggression or increase

its probability or intensity, it is neither a necessary nor a sufficient

condition for aggression.

Neuropsychological perspective

Extension

of the stimuli of the fighting reactions: At the beginning of life, the

human infant struggles indiscriminately against any restraining force,

whether it be another human being or a blanket which confines their

movements. There is no inherited susceptibility to social stimuli as

distinct from other stimulation, in anger. At a later date the child

learns that certain actions, such as striking, scolding, and screaming,

are effective toward persons, but not toward things. In adults, though

the infantile response is still sometimes seen, the fighting reaction

becomes fairly well limited to stimuli whose hurting or restraining

influence can be thrown off by physical violence.

Differences between related concepts

Raymond

Novaco of University of California Irvine, who since 1975 has published

a plethora of literature on the subject, stratified anger into three

modalities: cognitive (appraisals), somatic-affective (tension and agitations), and behavioral (withdrawal and antagonism).

The words annoyance and rage

are often imagined to be at opposite ends of an emotional continuum:

mild irritation and annoyance at the low end and fury or murderous rage

at the high end. Rage problems are conceptualized as "the inability to

process emotions or life's experiences" either because the capacity to regulate emotion (Schore, 1994)

has never been sufficiently developed or because it has been

temporarily lost due to more recent trauma. Rage is understood as raw,

undifferentiated emotions, that spill out when another life event that

cannot be processed, no matter how trivial, puts more stress on the organism than it can bear.

Anger, when viewed as a protective response or instinct to a

perceived threat, is considered as positive. The negative expression of

this state is known as aggression. Acting on this misplaced state is rage due to possible potential errors in perception and judgment.

Examples

| Expressions of anger used negatively |

Reasoning

|

| Over-protective instinct and hostility |

To avoid conceived loss or fear that something will be taken away.

|

| Entitlement and frustration |

To prevent a change in functioning.

|

| Intimidation and rationalization |

To meet one's own needs.

|

Characteristics

William DeFoore, an anger management

writer, described anger as a pressure cooker, stating that "we can only

suppress or apply pressure against our anger for so long before it

erupts".

One simple dichotomy of anger expression is passive anger versus aggressive anger versus assertive anger. These three types of anger have some characteristic symptoms:

Passive anger

Passive anger can be expressed in the following ways:

- Dispassion, such as giving someone the cold shoulder or a fake smile, looking unconcerned or "sitting on the fence" while others sort things out, dampening feelings with substance abuse,

overreacting, oversleeping, not responding to another's anger,

frigidity, indulging in sexual practices that depress spontaneity and

make objects of participants, giving inordinate amounts of time to

machines, objects or intellectual pursuits, talking of frustrations but

showing no feeling.

- Evasiveness, such as turning one's back in a crisis, avoiding conflict, not arguing back, becoming phobic.

- Defeatism, such as setting yourself and others up for failure, choosing unreliable people to depend on, being accident prone, underachieving, sexual impotence, expressing frustration at insignificant things but ignoring serious ones.

- Obsessive behavior,

such as needing to be inordinately clean and tidy, making a habit of

constantly checking things, over-dieting or overeating, demanding that

all jobs be done perfectly.

- Psychological manipulation, such as provoking people to aggression and then patronizing them, provoking aggression but staying on the sidelines, emotional blackmail, false tearfulness, feigning illness, sabotaging relationships, using sexual provocation, using a third party to convey negative feelings, withholding money or resources.

- Secretive behavior, such as stockpiling resentments that are expressed behind people's backs, giving the silent treatment or under-the-breath mutterings, avoiding eye contact, putting people down, gossiping, anonymous complaints, poison pen letters, stealing, and conning.

- Self-blame, such as apologizing too often, being overly critical, inviting criticism.

Aggressive anger

The symptoms of aggressive anger are:

- Bullying,

such as threatening people directly, persecuting, insulting, pushing or

shoving, using power to oppress, shouting, driving someone off the

road, playing on people's weaknesses.

- Destruction, such as destroying objects as in vandalism, harming animals, child abuse, destroying a relationship, reckless driving, substance abuse.

- Grandiosity, such as showing off, expressing mistrust,

not delegating, being a sore loser, wanting center stage all the time,

not listening, talking over people's heads, expecting kiss and make-up

sessions to solve problems.

- Hurtfulness, such as violence, including sexual abuse and rape, verbal abuse, biased or vulgar jokes, breaking confidence, using foul language, ignoring people's feelings, willfully discriminating, blaming, punishing people for unwarranted deeds, labeling others.

- Risk-taking behavior, such as speaking too fast, walking too fast, driving too fast, reckless spending.

- Selfishness, such as ignoring others' needs, not responding to requests for help, queue jumping.

- Threats, such as frightening people by saying how one could harm them, their property or their prospects, finger pointing, fist shaking, wearing clothes or symbols associated with violent behavior, tailgating, excessively blowing a car horn, slamming doors.

- Unjust blaming, such as accusing other people for one's own mistakes, blaming people for your own feelings, making general accusations.

- Unpredictability, such as explosive rages over minor frustrations, attacking indiscriminately, dispensing unjust punishment, inflicting harm on others for the sake of it, illogical arguments.

- Vengeance, such as being over-punitive. This differs from retributive justice, as vengeance is personal, and possibly unlimited in scale.

Assertive anger

- Blame,

such as after a particular individual commits an action that's possibly

frowned upon, the particular person will resort to scolding. This is in

fact, common in discipline terms.

- Punishment,

the angry person will give a temporary punishment to an individual like

further limiting a child's will to do anything they want like playing

video games, reading, (excluding schoolwork) etc, after they did

something to cause trouble.

- Sternness, such as calling out a person on their behaviour, with their voices raised with utter disapproval/disappointment.

Six dimensions of anger expression

Anger

expression can take on many more styles than passive or aggressive.

Ephrem Fernandez has identified six dimensions of anger expression. They

relate to the direction of anger, its locus, reaction, modality,

impulsivity, and objective. Coordinates on each of these dimensions can

be connected to generate a profile of a person's anger expression style.

Among the many profiles that are theoretically possible in this system,

are the familiar profile of the person with explosive anger, profile of

the person with repressive anger, profile of the passive aggressive person, and the profile of constructive anger expression.

Ethnicity and culture

Much

research has explored whether the emotion of anger is experienced and

expressed differently depending on the culture. Matsumoto (2007)

conducted a study in which White-American and Asian participants needed

to express the emotions from a program called JACFEE (Japanese and

Caucasian Facial Expression of Emotion) in order to determine whether

Caucasian observers noticed any differences in expression of

participants of a different nationality. He found that participants were

unable to assign a nationality to people demonstrating expression of

anger, i.e. they could not distinguish ethnic-specific expressions of

anger.

Hatfield, Rapson, and Le (2009) conducted a study that measured ethnic

differences in emotional expression using participants from the

Philippines, Hawaii, China, and Europe. They concluded that there was a

difference between how someone expresses an emotion, especially the

emotion of anger in people with different ethnicities, based on

frequency, with Europeans showing the lowest frequency of expression of

negative emotions.

Other research investigates anger within different ethnic groups

who live in the same country. Researchers explored whether Black

Americans experience and express greater anger than Whites (Mabry &

Kiecolt, 2005). They found that, after controlling for sex and age,

Black participants did not feel or express more anger than Whites.

Deffenbacher and Swaim (1999) compared the expression of anger in

Mexican American people and White non-Hispanic American people. They

concluded that White non-Hispanic Americans expressed more verbal

aggression than Mexican Americans, although when it came to physical

aggression expressions there was no significant difference between both

cultures when it came to anger.

Causes

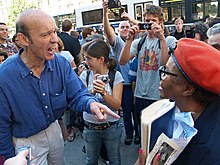

Some animals make loud sounds, attempt to look physically larger, bare their teeth, and stare.

The behaviors associated with anger are designed to warn aggressors to

stop their threatening behavior. Rarely does a physical altercation

occur without the prior expression of anger by at least one of the

participants. Displays of anger can be used as a manipulation strategy for social influence.

People feel really angry when they sense that they or someone

they care about has been offended, when they are certain about the

nature and cause of the angering event, when they are convinced someone

else is responsible, and when they feel they can still influence the

situation or cope with it.

For instance, if a person's car is damaged, they will feel angry if

someone else did it (e.g. another driver rear-ended it), but will feel

sadness instead if it was caused by situational forces (e.g. a

hailstorm) or guilt and shame if they were personally responsible (e.g.

he crashed into a wall out of momentary carelessness). Psychotherapist

Michael C. Graham defines anger in terms of our expectations and

assumptions about the world. Graham states anger almost always results when we are caught up "... expecting the world to be different than it is".

Usually, those who experience anger explain its arousal as a

result of "what has happened to them" and in most cases the described

provocations occur immediately before the anger experience. Such

explanations confirm the illusion that anger has a discrete external

cause. The angry person usually finds the cause of their anger in an

intentional, personal, and controllable aspect of another person's

behavior. This explanation, however, is based on the intuitions of the

angry person who experiences a loss in self-monitoring capacity and

objective observability as a result of their emotion. Anger can be of

multicausal origin, some of which may be remote events, but people

rarely find more than one cause for their anger.

According to Novaco, "Anger experiences are embedded or nested within

an environmental-temporal context. Disturbances that may not have

involved anger at the outset leave residues that are not readily

recognized but that operate as a lingering backdrop for focal

provocations (of anger)." According to Encyclopædia Britannica, an internal infection can cause pain which in turn can activate anger. According to cognitive consistency

theory, anger is caused by an inconsistency between a desired, or

expected, situation and the actually perceived situation, and triggers

responses, such as aggressive behavior, with the expected consequence of reducing the inconsistency.

Cognitive effects

Anger causes a reduction in cognitive ability and the accurate

processing of external stimuli. Dangers seem smaller, actions seem less

risky, ventures seem more likely to succeed, and unfortunate events seem

less likely. Angry people are more likely to make risky decisions, and

make less realistic risk assessments. In one study, test subjects primed

to feel angry felt less likely to suffer heart disease, and more likely

to receive a pay raise, compared to fearful people.

This tendency can manifest in retrospective thinking as well: in a 2005

study, angry subjects said they thought the risks of terrorism in the

year following 9/11 in retrospect were low, compared to what the fearful and neutral subjects thought.

In inter-group relationships, anger makes people think in more

negative and prejudiced terms about outsiders. Anger makes people less

trusting, and slower to attribute good qualities to outsiders.

When a group is in conflict with a rival group, it will feel more

anger if it is the politically stronger group and less anger when it is

the weaker.

Unlike other negative emotions like sadness and fear, angry people are more likely to demonstrate correspondence bias

– the tendency to blame a person's behavior more on his nature than on

his circumstances. They tend to rely more on stereotypes, and pay less

attention to details and more attention to the superficial. In this

regard, anger is unlike other "negative" emotions such as sadness and

fear, which promote analytical thinking.

An angry person tends to anticipate other events that might cause

them anger. They will tend to rate anger-causing events (e.g. being

sold a faulty car) as more likely than sad events (e.g. a good friend

moving away).

A person who is angry tends to place more blame on another person

for their misery. This can create a feedback, as this extra blame can

make the angry person angrier still, so they in turn place yet more

blame on the other person.

When people are in a certain emotional state, they tend to pay

more attention to, or remember, things that are charged with the same

emotion; so it is with anger. For instance, if you are trying to

persuade someone that a tax increase is necessary, if the person is

currently feeling angry you would do better to use an argument that

elicits anger ("more criminals will escape justice") than, say, an

argument that elicits sadness ("there will be fewer welfare benefits for

disabled children").

Also, unlike other negative emotions, which focus attention on all

negative events, anger only focuses attention on anger-causing events.

Anger can make a person more desiring of an object to which his

anger is tied. In a 2010 Dutch study, test subjects were primed to feel

anger or fear by being shown an image of an angry or fearful face, and

then were shown an image of a random object. When subjects were made to

feel angry, they expressed more desire to possess that object than

subjects who had been primed to feel fear.

Expressive strategies

As with any emotion, the display of anger can be feigned or exaggerated.

Studies by Hochschild and Sutton have shown that the show of anger is

likely to be an effective manipulation strategy in order to change and

design attitudes. Anger is a distinct strategy of social influence and

its use (e.g. belligerent behaviors) as a goal achievement mechanism

proves to be a successful strategy.

Larissa Tiedens, known for her studies of anger, claimed that

expression of feelings would cause a powerful influence not only on the perception of the expresser but also on their power position in the society. She studied the correlation

between anger expression and social influence perception. Previous

researchers, such as Keating, 1985 have found that people with angry

face expression were perceived as powerful and as in a high social position.

Similarly, Tiedens et al. have revealed that people who compared

scenarios involving an angry and a sad character, attributed a higher social status to the angry character.

Tiedens examined in her study whether anger expression promotes status

attribution. In other words, whether anger contributes to perceptions or

legitimization of others' behaviors. Her findings clearly indicated

that participants who were exposed to either an angry or a sad person

were inclined to express support for the angry person rather than for a

sad one. In addition, it was found that a reason for that decision

originates from the fact that the person expressing anger was perceived

as an ability owner, and was attributed a certain social status

accordingly.

Showing anger during a negotiation may increase the ability of the anger expresser to succeed in negotiation.

A study by Tiedens et al. indicated that the anger expressers were

perceived as stubborn, dominant and powerful. In addition, it was found

that people were inclined to easily give up to those who were perceived

by them as powerful and stubborn, rather than soft and submissive.

Based on these findings Sinaceur and Tiedens have found that people

conceded more to the angry side rather than for the non-angry one.

A question raised by Van Kleef et al. based on these findings was

whether expression of emotion influences others, since it is known that

people use emotional information to conclude about others' limits and

match their demands in negotiation accordingly. Van Kleef et al. wanted

to explore whether people give up more easily to an angry opponent or to

a happy opponent. Findings revealed that participants tended to be more

flexible toward an angry opponent compared with a happy opponent. These

results strengthen the argument that participants analyze the

opponent's emotion to conclude about their limits and carry out their

decisions accordingly.

Coping strategies

According to Leland R. Beaumont, each instance of anger demands making a choice. A person can respond with hostile action, including overt violence,

or they can respond with hostile inaction, such as withdrawing or

stonewalling. Other options include initiating a dominance contest;

harboring resentment; or working to better understand and constructively resolve the issue.

According to Raymond Novaco, there are a multitude of steps that

were researched in attempting to deal with this emotion. In order to

manage anger the problems involved in the anger should be discussed,

Novaco suggests. The situations leading to anger should be explored by

the person. The person is then tried to be imagery-based relieved of his

or her recent angry experiences.

Conventional therapies for anger involve restructuring thoughts

and beliefs to bring about a reduction in anger. These therapies often

come within the schools of CBT (or cognitive behavioral therapy) like modern systems such as REBT (rational emotive behavior therapy). Research shows that people who suffer from excessive anger often harbor and act on dysfunctional attributions, assumptions and evaluations

in specific situations. It has been shown that with therapy by a

trained professional, individuals can bring their anger to more

manageable levels.

The therapy is followed by the so-called "stress inoculation" in which

the clients are taught "relaxation skills to control their arousal and

various cognitive controls to exercise on their attention, thoughts,

images, and feelings. “Logic defeats anger, because anger, even when

it's justified, can quickly become irrational“ (American Psychological

Association). Even though there may be a rational reason to get angry,

frustrated actions may become irrational. Taking Deep breaths is an easy

first step to calming down. Once the anger has subsided a little,

accept that you are frustrated and move on. Lingering around the source

of frustration may bring the rage back.

The skills-deficit model states that poor social skills is what renders a person incapable of expressing anger in an appropriate manner.

Social skills training has been found to be an effective method for

reducing exaggerated anger by offering alternative coping skills to the

angry individual. Research has found that persons who are prepared for

aversive events find them less threatening, and excitatory reactions are

significantly reduced.

In a 1981 study, that used modeling, behavior rehearsal, and videotaped

feedback to increase anger control skills, showed increases in anger

control among aggressive youth in the study.

Research conducted with youthful offenders using a social skills

training program (aggression replacement training), found significant

reductions in anger, and increases in anger control.

Research has also found that antisocial personalities are more likely

to learn avoidance tasks when the consequences involved obtaining or

losing tangible rewards. Learning among antisocial personalities also

occurred better when they were involved with high intensity stimulation. Social learning theory states that positive stimulation was not compatible with hostile or aggressive reactions.

Anger research has also studied the effects of reducing anger among

adults with antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), with a social skills

program approach that used a low fear and high arousal group setting.

This research found that low fear messages were less provocative to the

ASPD population, and high positive arousal stimulated their ability to

concentrate, and subsequently learn new skills for anger reduction.

Cognitive behavioral affective therapy

A new integrative approach to anger treatment has been formulated by Fernandez (2010)

Termed CBAT, for cognitive behavioral affective therapy, this treatment

goes beyond conventional relaxation and reappraisal by adding cognitive

and behavioral techniques and supplementing them with affective

techniques to deal with the feeling of anger. The techniques are

sequenced contingently in three phases of treatment: prevention,

intervention, and postvention. In this way, people can be trained to

deal with the onset of anger, its progression, and the residual features

of anger.

Suppression

Modern psychologists point out that suppression

of anger may have harmful effects. The suppressed anger may find

another outlet, such as a physical symptom, or become more extreme. John W. Fiero cites Los Angeles riots of 1992

as an example of sudden, explosive release of suppressed anger. The

anger was then displaced as violence against those who had nothing to do

with the matter. There is also the case of Francine Hughes,

who suffered 13 years of domestic abuse. Her suppressed anger drove her

to kill her abuser husband. It is claimed that a majority of female

victims of domestic violence who suppress their aggressive feelings are

unable to recognize, experience, and process negative emotion and this

has a destabilizing influence on their perception of agency in their

relationships. Another example of widespread deflection of anger from its actual cause toward scapegoating, Fiero says, was the blaming of Jews for the economic ills of Germany by the Nazis.

However, psychologists have also criticized the "catharsis

theory" of aggression, which suggests that "unleashing" pent-up anger

reduces aggression.

On the other hand, there are experts who maintain that suppression does

not eliminate anger since it merely forbids the expression of anger and

this is also the case for repression, which merely hides anger from

awareness. There are also studies that link suppressed anger and medical conditions such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, and cancer. Suppressed or repressed anger is found to cause irritable bowel syndrome, eating disorders, and depression among women.

Suppression is also referred to as a form of "self-silencing", which is

described as a cognitive activity wherein an individual monitors the

self and eliminate thoughts and feelings that are perceived to be

dangerous to relationships. Anger suppression is also associated with higher rates of suicide.

Dual threshold model

Anger expression might have negative outcomes for individuals and organizations as well, such as decrease of productivity and increase of job stress,

however it could also have positive outcomes, such as increased work

motivation, improved relationships, increased mutual understanding etc.

(for ex. Tiedens, 2000).

A Dual Threshold Model of Anger in organizations by Geddes and

Callister, (2007) provides an explanation on the valence of anger

expression outcomes. The model suggests that organizational norms

establish emotion thresholds that may be crossed when employees feel

anger. The first "expression threshold" is crossed when an

organizational member conveys felt anger to individuals at work who are

associated with or able to address the anger-provoking situation. The

second "impropriety threshold" is crossed if or when organizational

members go too far while expressing anger such that observers and other

company personnel find their actions socially and/or culturally

inappropriate.

The higher probability of negative outcomes from workplace anger

likely will occur in either of two situations. The first is when

organizational members suppress rather than express their anger—that is,

they fail to cross the "expression threshold". In this instance

personnel who might be able to address or resolve the anger-provoking

condition or event remain unaware of the problem, allowing it to

continue, along with the affected individual's anger. The second is when

organizational members cross both thresholds—"double cross"— displaying

anger that is perceived as deviant. In such cases the angry person is

seen as the problem—increasing chances of organizational sanctions

against him or her while diverting attention away from the initial

anger-provoking incident. In contrast, a higher probability of positive

outcomes from workplace anger expression likely will occur when one's

expressed anger stays in the space between the expression and

impropriety thresholds. Here, one expresses anger in a way fellow

organizational members find acceptable, prompting exchanges and

discussions that may help resolve concerns to the satisfaction of all

parties involved. This space between the thresholds varies among

different organizations and also can be changed in organization itself:

when the change is directed to support anger displays; the space between

the thresholds will be expanded and when the change is directed to

suppressing such displays; the space will be reduced.

Physiology

Neuroscience has shown that emotions are generated by multiple structures in the brain.

The rapid, minimal, and evaluative processing of the emotional

significance of the sensory data is done when the data passes through

the amygdala in its travel from the sensory organs along certain neural pathways towards the limbic forebrain.

Emotion caused by discrimination of stimulus features, thoughts, or

memories however occurs when its information is relayed from the thalamus to the neocortex. Based on some statistical analysis, some scholars have suggested that the tendency for anger may be genetic. Distinguishing between genetic and environmental factors however requires further research and actual measurement of specific genes and environments.

In neuroimaging studies of anger, the most consistently activated region of the brain was the lateral orbitofrontal cortex. This region is associated with approach motivation and positive affective processes.

The external expression of anger can be found in physiological responses, facial expressions, body language, and at times in public acts of aggression. The rib cage tenses and breathing through the nose becomes faster, deeper, and irregular. Anger activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. The catecholamine activation is more strongly norepinephrine than epinephrine.

Heart rate and blood pressure increase. Blood flows to the hands.

Perspiration increases (particularly when the anger is intense).

The face flushes. The nostrils flare. The jaw tenses. The brow muscles

move inward and downward, fixing a hard stare on the target. The arms

are raised and a squared-off stance is adopted. The body is mobilized

for immediate action, often manifesting as a subjective sense of

strength, self-assurance, and potency. This may encourage the impulse to

strike out.

Philosophical perspectives

Ancient history

Ancient

Greek philosophers, describing and commenting on the uncontrolled

anger, particularly toward slaves, in their society generally showed a

hostile attitude towards anger. Galen and Seneca

regarded anger as a kind of madness. They all rejected the spontaneous,

uncontrolled fits of anger and agreed on both the possibility and value

of controlling anger. There were however disagreements regarding the

value of anger. For Seneca, anger was "worthless even for war". Seneca

believed that the disciplined Roman army was regularly able to beat the Germans, who were known for their fury. He argued that "... in sporting contests, it is a mistake to become angry".

Aristotle

on the other hand, ascribed some value to anger that has arisen from

perceived injustice because it is useful for preventing injustice. Furthermore, the opposite of anger is a kind of insensibility, Aristotle stated.

The difference in people's temperaments was generally viewed as a

result of the different mix of qualities or humors people contained.

Seneca held that "red-haired and red-faced people are hot-tempered

because of excessive hot and dry humors".

Ancient philosophers rarely refer to women's anger at all, according to

Simon Kemp and K.T. Strongman perhaps because their works were not

intended for women. Some of them that discuss it, such as Seneca,

considered women to be more prone to anger than men.

Control methods

Seneca

addresses the question of mastering anger in three parts: 1. how to

avoid becoming angry in the first place 2. how to cease being angry and

3. how to deal with anger in others.

Seneca suggests, to avoid becoming angry in the first place, that the

many faults of anger should be repeatedly remembered. One should avoid

being too busy or dealing with anger-provoking people. Unnecessary

hunger or thirst should be avoided and soothing music be listened to. To cease being angry, Seneca suggests

one

to check speech and impulses and be aware of particular sources of

personal irritation. In dealing with other people, one should not be too

inquisitive: It is not always soothing to hear and see everything. When

someone appears to slight you, you should be at first reluctant to

believe this, and should wait to hear the full story. You should also

put yourself in the place of the other person, trying to understand his

motives and any extenuating factors, such as age or illness."

Seneca further advises daily self-inquisition about one's bad habit.

To deal with anger in others, Seneca suggests that the best reaction is

to simply keep calm. A certain kind of deception, Seneca says, is

necessary in dealing with angry people.

Galen repeats Seneca's points but adds a new one: finding a guide

and teacher can help the person in controlling their passions. Galen

also gives some hints for finding a good teacher.

Both Seneca and Galen (and later philosophers) agree that the process

of controlling anger should start in childhood on grounds of

malleability. Seneca warns that this education should not blunt the

spirit of the children nor should they be humiliated or treated

severely. At the same time, they should not be pampered. Children,

Seneca says, should learn not to beat their playmates and not to become

angry with them. Seneca also advises that children's requests should not

be granted when they are angry.

Post-classical history

During the period of the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages,

philosophers elaborated on the existing conception of anger, many of

whom did not make major contributions to the concept. For example, many

medieval philosophers such as Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Roger Bacon and Thomas Aquinas agreed with ancient philosophers that animals cannot become angry. On the other hand, al-Ghazali

(Algazel), who often disagreed with Aristotle and Ibn Sina on many

issues, argued that animals do possess anger as one of the three

"powers" in their heart, the other two being appetite and impulse. He also argued that animal will is "conditioned by anger and appetite" in contrast to human will which is "conditioned by the intellect". A common medieval belief was that those prone to anger had an excess of yellow bile or choler (hence the word "choleric").

This belief was related to Seneca's belief that "red-haired and

red-faced people are hot-tempered because of excessive hot and dry

humors".

By gender

Wrath

was sinful because of the social problems it caused, sometimes even

homicide. It served to ignore those who are present, contradicts those

who are absent, produces insults, and responds harshly to insults that

are received.

Aristotle felt that anger or wrath was a natural outburst of

self-defense in situations where people felt they had been wronged.

Aquinas felt that if anger was justified, it was not a sin. For example,

"He that is angry without cause, shall be in danger; but he that is

angry with cause, shall not be in danger: for without anger, teaching

will be useless, judgments unstable, crimes unchecked. Therefore to be

angry is not always an evil."

The concept of wrath contributed to a definition of gender and

power. Many medieval authors in 1200 agreed the differences between men

and women were based on complexion, shape, and disposition. Complexion

involved the balance of the four fundamental qualities of heat,

coldness, moistness, and dryness. When various combinations of these

qualities are made they define groups of certain people as well as

individuals. Hippocrates, Aristotle, and Galen all agreed on that, in

terms of biology and sexual differentiation, heat was the most important

of the qualities because it determined shape and disposition.

Disposition included a balance of the previous four qualities, the four

elements and the four humors. For example, the element of fire shared

the qualities of heat and dryness: fire dominated in yellow bile or

choler, meaning a choleric person was more or hot and dry than others.

Hot and dry individuals were active, dominant, and aggressive. The

opposite was true with the element of water. Water, is cold and moist,

related closely to phlegm: people with more phlegmatic personalities

were passive and submissive. While these trait clusters varied from

individual to individual most authors in the Middle Ages assumed certain

clusters of traits characterized men more than women and vice versa.

Women

Scholars

posted that females were seen by authors in the Middle Ages to be more

phlegmatic (cold and wet) than males, meaning females were more

sedentary and passive than males.

Women's passive nature appeared "natural" due to their lack of power

when compared to men. Aristotle identified traits he believed women

shared: female, feminine, passive, focused on matter, inactive, and

inferior. Thus medieval women were supposed to act submissively toward

men and relinquish control to their husbands. However Hildegard of Bingen

believed women were fully capable of anger. While most women were

phlegmatic, individual women under certain circumstances could also be

choleric.

Men

Medieval scholars believed most men were choleric, or hot and dry. Thus

they were dominant and aggressive. (Barton) Aristotle also identified

characteristics of men: male, masculine, active, focused on form,

potent, outstanding, and superior. Men were aware of the power they

held. Given their choleric "nature", men exhibited hot temperatures and

were quick to anger. Peter of Albano

once said, "The male's spirit, is lively, given to violent impulse; [it

is] slow getting angry and slower being calmed." Medieval ideas of

gender assumed men were more rational than women. Masculinity involved a

wide range of possible behaviors, and men were not angry all the time.

Every man's humoral balance was different, some men were strong, others weak, also some more prone to wrath then others. There are those who view anger as a manly act. For instance, David Brakke maintained:

because

anger motivated a man to action in righting wrongs to himself and

others, because its opposite appeared to be passivity in the face of

challenges from other males, because – to put it simply – it raised the

body's temperature, anger appeared to be a characteristic of

masculinity, a sign that a man was indeed a manly man.

Control methods

Maimonides

considered being given to uncontrollable passions as a kind of illness.

Like Galen, Maimonides suggested seeking out a philosopher for curing

this illness just as one seeks out a physician for curing bodily

illnesses. Roger Bacon elaborates Seneca's advices. Many medieval

writers discuss at length the evils of anger and the virtues of

temperance. In a discussion of confession, John Mirk, an English 14th-century Augustinian writer, tells priests how to advise the penitent by considering the spiritual and social consequences of anger:

Agaynes wraþþe hys helpe schal be,

Ʒef he haue grace in herte to se

How aungelus, when he ys wroth,

From hym faste flen and goth,

And fendes faste to hym renneth,

And wyþ fuyre of helle hys herte breneth,

And maketh hym so hote & hegh,

Þat no mon may byde hym negh.

'Against wrath his help shall be,

if he has grace in heart to see,

how angels, should his anger rise,

flee fast from him and go

and demons run to him in haste;

hell's fury burns his heart

and makes him so hot and high

that none may stand him nigh.

In The Canon of Medicine, Ibn Sina (Avicenna) modified the theory of temperaments and argued that anger heralded the transition of melancholia to mania, and explained that humidity inside the head can contribute to such mood disorders.

On the other hand, Ahmed ibn Sahl al-Balkhi classified anger (along with aggression) as a type of neurosis, while al-Ghazali argued that anger takes form in rage, indignation and revenge, and that "the powers of the soul become balanced if it keeps anger under control".

Modern perspectives

Immanuel Kant rejects revenge as vicious. Regarding the latter, David Hume argues that because "anger and hatred are passions inherent in our very frame and constitution, the lack of them is sometimes evidence of weakness and imbecility". Martha Nussbaum has also agreed that even "great injustice" is no "excuse for childish and undisciplined behavior".

Two main differences between the modern understanding and ancient

understanding of anger can be detected, Kemp and Strongman state: one is

that early philosophers were not concerned with possible harmful

effects of the suppression of anger; the other is that, recently, studies of anger take the issue of gender differences into account.

Soraya Chemaly has in contrast argued that anger is "a critically

useful and positive emotion" which "warns us, as humans, that something

is wrong and needs to change" when "being threatened with indignity,

physical harm, humiliation and unfairness" and therefore "a powerful

force for political good". Furthermore, she argues that women and minorities are not allowed to be angry to the same extent as white men. In a similar vein, Rebecca Traister has argued that holding back anger has been an impediment to the progress of women's rights.

The American psychologist Albert Ellis

has suggested that anger, rage, and fury partly have roots in the

philosophical meanings and assumptions through which human beings

interpret transgression.

According to Ellis, these emotions are often associated and related to

the leaning humans have to absolutistically depreciating and damning

other peoples' humanity when their personal rules and domain are

transgressed.

Religious perspectives

Judaism

In Judaism, anger is a negative trait. In the Book of Genesis, Jacob

condemned the anger that had arisen in his sons Simon and Levi: "Cursed

be their anger, for it was fierce; and their wrath, for it was cruel."

Restraining oneself from anger is seen as noble and desirable, as Ethics of the Fathers states:

Ben Zoma said:

Who is strong? He who subdues his evil inclination, as it is stated,

"He who is slow to anger is better than a strong man, and he who masters

his passions is better than one who conquers a city" (Proverbs 16:32).

Maimonides rules that one who becomes angry is as though that person had worshipped idols. Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi explains that the parallel between anger and idol worship is that by becoming angry, one shows a disregard of Divine Providence

– whatever had caused the anger was ultimately ordained from Above –

and that through coming to anger one thereby denies the hand of God in one's life.

In its section dealing with ethical traits a person should adopt, the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch

states: "Anger is also a very evil trait and it should be avoided at

all costs. You should train yourself not to become angry even if you

have a good reason to be angry."

In modern writings, Rabbi Harold Kushner finds no grounds for anger toward God because "our misfortunes are none of His doing". In contrast to Kushner's reading of the Bible,

David Blumenthal finds an "abusing God" whose "sometimes evil" actions

evoke vigorous protest, but without severing the protester's

relationship with God.

Christianity

Both Catholic and Protestant writers have addressed anger.

Catholic

Wrath is one of the Seven Deadly Sins in Catholicism; and yet the Catechism of the Catholic Church

states (canons 1772 and 1773) that anger is among the passions, and

that "in the passions, as movements of the sensitive appetite, there is

neither good nor evil". The neutral act of anger becomes the sin of

wrath when it's directed against an innocent person, when it's unduly

unbending or long-lasting, or when it desires excessive punishment. "If

anger reaches the point of a deliberate desire to kill or seriously

wound a neighbor, it is gravely against charity; it is a mortal sin"

(CCC 2302). Hatred is the sin of desiring that someone else may suffer

misfortune or evil, and is a mortal sin when one desires grave harm (CCC

2302-03).

Medieval Christianity vigorously denounced wrath as one of the seven cardinal, or deadly sins, but some Christian writers at times regarded the anger caused by injustice as having some value. Saint Basil viewed anger as a "reprehensible temporary madness". Joseph F. Delany in the Catholic Encyclopedia

(1914) defines anger as "the desire of vengeance" and states that a

reasonable vengeance and passion is ethical and praiseworthy. Vengeance

is sinful when it exceeds its limits in which case it becomes opposed to

justice and charity. For example, "vengeance upon one who has not

deserved it, or to a greater extent than it has been deserved, or in

conflict with the dispositions of law, or from an improper motive" are

all sinful. An unduly vehement vengeance is considered a venial sin unless it seriously goes counter to the love of God or of one's neighbor.

A more positive view of anger is espoused by Roman Catholic pastoral theologian Henri J.M. Nouwen. Father Nouwen points to the spiritual benefits in anger toward God as found in both the Old Testament and New Testament of the Bible.

In the Bible, says Father Nouwen, "it is clear that only by expressing

our anger and hatred directly to God will we come to know the fullness

of both his love and our freedom".

Georges Bernanos illustrates Nouwen's position in his novel The Diary of a Country Priest.

The countess gave birth to the son she had long wanted, but the child

died. She was fiercely angry. When the priest called, the countess

vented her anger toward her daughter and husband, then at the priest who

responded gently, "open your heart to [God]". The countess rejoined,

"I've ceased to bother about God. When you've forced me to admit that I

hate Him, will you be any better off?" The priest continued, "you no

longer hate Him. Hate is indifference and contempt. Now at last you're

face to face with Him ... Shake your fist at

Him, spit in His face, scourge Him." The countess did what the priest

counseled. By confessing her hate, she was enabled to say, "all's well".

Protestant

Everyone experiences anger, Andrew D. Lester observes, and

furthermore anger can serve as "a spiritual friend, a spiritual guide,

and a spiritual ally". Denying and suppressing anger is contrary to St. Paul's admonition in his Epistle to the Ephesians 4:26.

When anger toward God is denied and suppressed, it interferes with an

individual's relation with God. However, expressing one's anger toward

God can deepen the relationship. C. FitzSimons Allison holds that "we worship God by expressing our honest anger at him".

Biblical scholar Leonard Pine concludes from his studies in the Book of Habakkuk that "far from being a sin, proper remonstration with God is the activity of a healthy faith relationship with Him". Other biblical examples of anger toward God include the following:

- Moses was angry with God for mistreating his people: "Lord, why have you mistreated [lit. done evil to] this people?" (Book of Exodus 5:22).

- Naomi

was angry with God after the death of her husband and two sons: "The

Almighty has dealt bitterly with me. The Almighty has brought calamity

upon me" (Book of Ruth 1:20–21 abr).

- Elijah

was angry with God after the son of the widow died: "O Lord my God,

have you brought calamity even upon the widow with whom I am staying, by

killing her son?" (1 Kings 17:20).

- Job was angry with God: "You have turned cruel to me; with the might of your hand you persecute me" (Book of Job 30:21).

- Jeremiah was angry with God for deceiving his people: "Ah, Lord God, how utterly you have deceived this people and Jerusalem" (Book of Jeremiah 4:10).

Hinduism

In Hinduism,

anger is equated with sorrow as a form of unrequited desire. The

objects of anger are perceived as a hindrance to the gratification of

the desires of the angry person.

Alternatively if one thinks one is superior, the result is grief. Anger

is considered to be packed with more evil power than desire. In the Bhagavad Gita Krishna

regards greed, anger, and lust as signs of ignorance that lead to

perpetual bondage. As for the agitations of the bickering mind, they are

divided into two divisions. The first is called avirodha-prīti, or

unrestricted attachment, and the other is called virodha-yukta-krodha,

anger arising from frustration. Adherence to the philosophy of the

Māyāvādīs, belief in the fruitive results of the karma-vādīs, and belief

in plans based on materialistic desires are called avirodha-prīti.

Jñānīs, karmīs and materialistic planmakers generally attract the

attention of conditioned souls, but when the materialists cannot

fulfill their plans and when their devices are frustrated, they become

angry. Frustration of material desires produces anger.

Buddhism

Anger is defined in Buddhism

as: "being unable to bear the object, or the intention to cause harm to

the object". Anger is seen as aversion with a stronger exaggeration,

and is listed as one of the five hindrances. Buddhist monks, such as Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibetans in exile, sometimes get angry.

However, there is a difference; most often a spiritual person is aware

of the emotion and the way it can be handled. Thus, in response to the

question: "Is any anger acceptable in Buddhism?' the Dalai Lama

answered:

Buddhism

in general teaches that anger is a destructive emotion and although

anger might have some positive effects in terms of survival or moral

outrage, I do not accept that anger of any kind as [sic] a virtuous emotion nor aggression as constructive behavior. The Gautama Buddha [sic] has taught that there are three basic kleshas at the root of samsara

(bondage, illusion) and the vicious cycle of rebirth. These are greed,

hatred, and delusion—also translatable as attachment, anger, and

ignorance. They bring us confusion and misery rather than peace,

happiness, and fulfillment. It is in our own self-interest to purify and

transform them.

Buddhist scholar and author Geshe Kelsang Gyatso has also explained Buddha's teaching on the spiritual imperative to identify anger and overcome it by transforming difficulties:

When things go wrong in our life and we encounter difficult situations,

we tend to regard the situation itself as our problem, but in reality

whatever problems we experience come from the side of the mind. If we

responded to difficult situations with a positive or peaceful mind they

would not be problems for us. Eventually, we might even regard them as

challenges or opportunities for growth and development. Problems arise

only if we respond to difficulties with a negative state of mind.

Therefore if we want to be free from problems, we must transform our

mind.

The Buddha himself on anger:

An angry person is ugly & sleeps poorly. Gaining a profit, he

turns it into a loss, having done damage with word & deed. A person

overwhelmed with anger destroys his wealth. Maddened with anger, he

destroys his status. Relatives, friends, & colleagues avoid him.

Anger brings loss. Anger inflames the mind. He doesn't realize that his

danger is born from within. An angry person doesn't know his own

benefit. An angry person doesn't see the Dharma.

A man conquered by anger is in a mass of darkness. He takes pleasure in

bad deeds as if they were good, but later, when his anger is gone, he

suffers as if burned with fire. He is spoiled, blotted out, like fire

enveloped in smoke. When anger spreads, when a man becomes angry, he has

no shame, no fear of evil, is not respectful in speech. For a person

overcome with anger, nothing gives light.

Islam

A verse in the third surah of the Quran instructs people to restrain their anger.

Anger (Arabic:غضب, ghadab) in Islam is considered to be instigated by Satan (Shaitan). Factors stated to lead to anger include selfishness, arrogance and excessive ambition. Islamic teachings also state that anger hinders the faith (iman) of a person. The Quran attributes anger to prophets and believers as well as Muhammad's enemies. It mentions the anger of Moses (Musa) against his people for worshiping a golden calf and at the moment when Moses strikes an Egyptian for fighting against an Israelite. The anger of Jonah (Yunus) is also mentioned in the Quran, which led to his departure from the people of Nineveh and his eventual realization of his error and his repentance. The removal of anger from the hearts of believers by God (Arabic: [[Allah|الله]] Allāh) after the fighting against Muhammad's enemies is over. In general, suppression of anger (Arabic: کاظم, kazm) is deemed a praiseworthy quality in the hadis. Ibn Abdil Barr,

the Andalusian Maliki jurist explains that controlling anger is the

door way for restraining other blameworthy traits ego and envy, since

these two are less powerful than anger. The hadis state various ways to

diminish, prevent and control anger. One of these methods is to perform a

ritual ablution,

a different narration states that the angry person should lie down and

other narrations instructs the angry person to invoke God and seek

refuge from the Devil, by reciting I take refuge with Allah/God from the accursed Devil.

It has also been stated by the Imam Ali, the "Commander of the

faithful" and the son-in-law of prophet Muhammad that "A moment of

patience in a moment of anger saves a thousand moments of regret." As

well as "Anger begins with madness, and ends in regret."

Divine retribution

In many religions, anger is frequently attributed to God or gods.

Primitive people held that gods were subject to anger and revenge in

anthropomorphic fashion. The Hebrew Bible says that opposition to God's Will results in God's anger. Reform rabbi Kaufmann Kohler explains:

God is not an intellectual

abstraction, nor is He conceived as a being indifferent to the doings of

man; and His pure and lofty nature resents most energetically anything

wrong and impure in the moral world: "O Lord, my God, mine Holy One ... Thou art of eyes too pure to behold evil, and canst not look on iniquity."

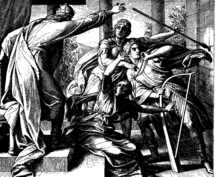

Christians believe in God's anger at the sight of evil. This anger is

not inconsistent with God's love, as demonstrated in the Gospel where

the righteous indignation of Christ is shown in the Cleansing of the Temple. Christians believe that those who reject His revealed Word, Jesus, condemn themselves, and are not condemned by the wrath of God.