| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Keynesian_economics |

Keynesian economics (/ˈkeɪnziən/ KAYN-zee-ən; sometimes Keynesianism, named after the economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output and inflation. In the Keynesian view, aggregate demand does not necessarily equal the productive capacity of the economy. Instead, it is influenced by a host of factors – sometimes behaving erratically – affecting production, employment, and inflation.

Keynesian economists generally argue that aggregate demand is volatile and unstable and that, consequently, a market economy often experiences inefficient macroeconomic outcomes – a recession, when demand is low, and inflation, when demand is high. Further, they argue that these economic fluctuations can be mitigated by economic policy responses coordinated between government and central bank. In particular, fiscal policy actions (taken by the government) and monetary policy actions (taken by the central bank), can help stabilize economic output, inflation, and unemployment over the business cycle. Keynesian economists generally advocate a market economy – predominantly private sector, but with an active role for government intervention during recessions and depressions.

Keynesian economics developed during and after the Great Depression from the ideas presented by Keynes in his 1936 book, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Keynes' approach was a stark contrast to the aggregate supply-focused classical economics that preceded his book. Interpreting Keynes's work is a contentious topic, and several schools of economic thought claim his legacy.

Keynesian economics, as part of the neoclassical synthesis, served as the standard macroeconomic model in the developed nations during the later part of the Great Depression, World War II, and the post-war economic expansion (1945–1973). It lost some influence following the oil shock and resulting stagflation of the 1970s. Keynesian economics was later redeveloped as New Keynesian economics, becoming part of the contemporary new neoclassical synthesis, that forms one current-day theory on macroeconomics. The advent of the financial crisis of 2007–2008 sparked renewed interest in Keynesian thought.

Historical context

Pre-Keynesian macroeconomics

Macroeconomics is the study of the factors applying to an economy as a whole. Important macroeconomic variables include the overall price level, the interest rate, the level of employment, and income (or equivalently output) measured in real terms.

The classical tradition of partial equilibrium theory had been to split the economy into separate markets, each of whose equilibrium conditions could be stated as a single equation determining a single variable. The theoretical apparatus of supply and demand curves developed by Fleeming Jenkin and Alfred Marshall provided a unified mathematical basis for this approach, which the Lausanne School generalized to general equilibrium theory.

For macroeconomics, relevant partial theories included the Quantity theory of money determining the price level and the classical theory of the interest rate. In regards to employment, the condition referred to by Keynes as the "first postulate of classical economics" stated that the wage is equal to the marginal product, which is a direct application of the marginalist principles developed during the nineteenth century (see The General Theory). Keynes sought to supplant all three aspects of the classical theory.

Precursors of Keynesianism

Although Keynes's work was crystallized and given impetus by the advent of the Great Depression, it was part of a long-running debate within economics over the existence and nature of general gluts. A number of the policies Keynes advocated to address the Great Depression (notably government deficit spending at times of low private investment or consumption), and many of the theoretical ideas he proposed (effective demand, the multiplier, the paradox of thrift), had been advanced by various authors in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Keynes's unique contribution was to provide a general theory of these, which proved acceptable to the economic establishment.

An intellectual precursor of Keynesian economics was underconsumption theories associated with John Law, Thomas Malthus, the Birmingham School of Thomas Attwood, and the American economists William Trufant Foster and Waddill Catchings, who were influential in the 1920s and 1930s. Underconsumptionists were, like Keynes after them, concerned with failure of aggregate demand to attain potential output, calling this "underconsumption" (focusing on the demand side), rather than "overproduction" (which would focus on the supply side), and advocating economic interventionism. Keynes specifically discussed underconsumption (which he wrote "under-consumption") in the General Theory, in Chapter 22, Section IV and Chapter 23, Section VII.

Numerous concepts were developed earlier and independently of Keynes by the Stockholm school during the 1930s; these accomplishments were described in a 1937 article, published in response to the 1936 General Theory, sharing the Swedish discoveries.

The paradox of thrift was stated in 1892 by John M. Robertson in his The Fallacy of Saving, in earlier forms by mercantilist economists since the 16th century, and similar sentiments date to antiquity.

Keynes's early writings

In 1923 Keynes published his first contribution to economic theory, A Tract on Monetary Reform, whose point of view is classical but incorporates ideas that later played a part in the General Theory. In particular, looking at the hyperinflation in European economies, he drew attention to the opportunity cost of holding money (identified with inflation rather than interest) and its influence on the velocity of circulation.

In 1930 he published A Treatise on Money, intended as a comprehensive treatment of its subject "which would confirm his stature as a serious academic scholar, rather than just as the author of stinging polemics", and marks a large step in the direction of his later views. In it, he attributes unemployment to wage stickiness and treats saving and investment as governed by independent decisions: the former varying positively with the interest rate, the latter negatively. The velocity of circulation is expressed as a function of the rate of interest. He interpreted his treatment of liquidity as implying a purely monetary theory of interest.

Keynes's younger colleagues of the Cambridge Circus and Ralph Hawtrey believed that his arguments implicitly assumed full employment, and this influenced the direction of his subsequent work. During 1933, he wrote essays on various economic topics "all of which are cast in terms of movement of output as a whole".

Development of The General Theory

At the time that Keynes's wrote the General Theory, it had been a tenet of mainstream economic thought that the economy would automatically revert to a state of general equilibrium: it had been assumed that, because the needs of consumers are always greater than the capacity of the producers to satisfy those needs, everything that is produced would eventually be consumed once the appropriate price was found for it. This perception is reflected in Say's law and in the writing of David Ricardo, which states that individuals produce so that they can either consume what they have manufactured or sell their output so that they can buy someone else's output. This argument rests upon the assumption that if a surplus of goods or services exists, they would naturally drop in price to the point where they would be consumed.

Given the backdrop of high and persistent unemployment during the Great Depression, Keynes argued that there was no guarantee that the goods that individuals produce would be met with adequate effective demand, and periods of high unemployment could be expected, especially when the economy was contracting in size. He saw the economy as unable to maintain itself at full employment automatically, and believed that it was necessary for the government to step in and put purchasing power into the hands of the working population through government spending. Thus, according to Keynesian theory, some individually rational microeconomic-level actions such as not investing savings in the goods and services produced by the economy, if taken collectively by a large proportion of individuals and firms, can lead to outcomes wherein the economy operates below its potential output and growth rate.

Prior to Keynes, a situation in which aggregate demand for goods and services did not meet supply was referred to by classical economists as a general glut, although there was disagreement among them as to whether a general glut was possible. Keynes argued that when a glut occurred, it was the over-reaction of producers and the laying off of workers that led to a fall in demand and perpetuated the problem. Keynesians therefore advocate an active stabilization policy to reduce the amplitude of the business cycle, which they rank among the most serious of economic problems. According to the theory, government spending can be used to increase aggregate demand, thus increasing economic activity, reducing unemployment and deflation.

Origins of the multiplier

The Liberal Party fought the 1929 General Election on a promise to "reduce levels of unemployment to normal within one year by utilising the stagnant labour force in vast schemes of national development". David Lloyd George launched his campaign in March with a policy document, We can cure unemployment, which tentatively claimed that, "Public works would lead to a second round of spending as the workers spent their wages." Two months later Keynes, then nearing completion of his Treatise on money, and Hubert Henderson collaborated on a political pamphlet seeking to "provide academically respectable economic arguments" for Lloyd George's policies. It was titled Can Lloyd George do it? and endorsed the claim that "greater trade activity would make for greater trade activity ... with a cumulative effect". This became the mechanism of the "ratio" published by Richard Kahn in his 1931 paper "The relation of home investment to unemployment", described by Alvin Hansen as "one of the great landmarks of economic analysis". The "ratio" was soon rechristened the "multiplier" at Keynes's suggestion.

The multiplier of Kahn's paper is based on a respending mechanism familiar nowadays from textbooks. Samuelson puts it as follows:

Let’s suppose that I hire unemployed resources to build a $1000 woodshed. My carpenters and lumber producers will get an extra $1000 of income... If they all have a marginal propensity to consume of 2/3, they will now spend $666.67 on new consumption goods. The producers of these goods will now have extra incomes... they in turn will spend $444.44 ... Thus an endless chain of secondary consumption respending is set in motion by my primary investment of $1000.

Samuelson's treatment closely follows Joan Robinson's account of 1937 and is the main channel by which the multiplier has influenced Keynesian theory. It differs significantly from Kahn's paper and even more from Keynes's book.

The designation of the initial spending as "investment" and the employment-creating respending as "consumption" echoes Kahn faithfully, though he gives no reason why initial consumption or subsequent investment respending shouldn't have exactly the same effects. Henry Hazlitt, who considered Keynes as much a culprit as Kahn and Samuelson, wrote that ...

... in connection with the multiplier (and indeed most of the time) what Keynes is referring to as "investment" really means any addition to spending for any purpose... The word "investment" is being used in a Pickwickian, or Keynesian, sense.

Kahn envisaged money as being passed from hand to hand, creating employment at each step, until it came to rest in a cul-de-sac (Hansen's term was "leakage"); the only culs-de-sac he acknowledged were imports and hoarding, although he also said that a rise in prices might dilute the multiplier effect. Jens Warming recognised that personal saving had to be considered, treating it as a "leakage" (p. 214) while recognising on p. 217 that it might in fact be invested.

The textbook multiplier gives the impression that making society richer is the easiest thing in the world: the government just needs to spend more. In Kahn's paper, it is harder. For him, the initial expenditure must not be a diversion of funds from other uses, but an increase in the total expenditure: something impossible – if understood in real terms – under the classical theory that the level of expenditure is limited by the economy's income/output. On page 174, Kahn rejects the claim that the effect of public works is at the expense of expenditure elsewhere, admitting that this might arise if the revenue is raised by taxation, but says that other available means have no such consequences. As an example, he suggests that the money may be raised by borrowing from banks, since ...

... it is always within the power of the banking system to advance to the Government the cost of the roads without in any way affecting the flow of investment along the normal channels.

This assumes that banks are free to create resources to answer any demand. But Kahn adds that ...

... no such hypothesis is really necessary. For it will be demonstrated later on that, pari passu with the building of roads, funds are released from various sources at precisely the rate that is required to pay the cost of the roads.

The demonstration relies on "Mr Meade's relation" (due to James Meade) asserting that the total amount of money that disappears into culs-de-sac is equal to the original outlay, which in Kahn's words "should bring relief and consolation to those who are worried about the monetary sources" (p. 189).

A respending multiplier had been proposed earlier by Hawtrey in a 1928 Treasury memorandum ("with imports as the only leakage"), but the idea was discarded in his own subsequent writings. Soon afterwards the Australian economist Lyndhurst Giblin published a multiplier analysis in a 1930 lecture (again with imports as the only leakage). The idea itself was much older. Some Dutch mercantilists had believed in an infinite multiplier for military expenditure (assuming no import "leakage"), since ...

... a war could support itself for an unlimited period if only money remained in the country ... For if money itself is "consumed", this simply means that it passes into someone else's possession, and this process may continue indefinitely.

Multiplier doctrines had subsequently been expressed in more theoretical terms by the Dane Julius Wulff (1896), the Australian Alfred de Lissa (late 1890s), the German/American Nicholas Johannsen (same period), and the Dane Fr. Johannsen (1925/1927). Kahn himself said that the idea was given to him as a child by his father.

Public policy debates

As the 1929 election approached "Keynes was becoming a strong public advocate of capital development" as a public measure to alleviate unemployment. Winston Churchill, the Conservative Chancellor, took the opposite view:

It is the orthodox Treasury dogma, steadfastly held ... [that] very little additional employment and no permanent additional employment can, in fact, be created by State borrowing and State expenditure.

Keynes pounced on a chink in the Treasury view. Cross-examining Sir Richard Hopkins, a Second Secretary in the Treasury, before the Macmillan Committee on Finance and Industry in 1930 he referred to the "first proposition" that "schemes of capital development are of no use for reducing unemployment" and asked whether "it would be a misunderstanding of the Treasury view to say that they hold to the first proposition". Hopkins responded that "The first proposition goes much too far. The first proposition would ascribe to us an absolute and rigid dogma, would it not?"

Later the same year, speaking in a newly created Committee of Economists, Keynes tried to use Kahn's emerging multiplier theory to argue for public works, "but Pigou's and Henderson's objections ensured that there was no sign of this in the final product". In 1933 he gave wider publicity to his support for Kahn's multiplier in a series of articles titled "The road to prosperity" in The Times newspaper.

A. C. Pigou was at the time the sole economics professor at Cambridge. He had a continuing interest in the subject of unemployment, having expressed the view in his popular Unemployment (1913) that it was caused by "maladjustment between wage-rates and demand" – a view Keynes may have shared prior to the years of the General Theory. Nor were his practical recommendations very different: "on many occasions in the thirties" Pigou "gave public support ... to State action designed to stimulate employment". Where the two men differed is in the link between theory and practice. Keynes was seeking to build theoretical foundations to support his recommendations for public works while Pigou showed no disposition to move away from classical doctrine. Referring to him and Dennis Robertson, Keynes asked rhetorically: "Why do they insist on maintaining theories from which their own practical conclusions cannot possibly follow?"

The General Theory

Keynes set forward the ideas that became the basis for Keynesian economics in his main work, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). It was written during the Great Depression, when unemployment rose to 25% in the United States and as high as 33% in some countries. It is almost wholly theoretical, enlivened by occasional passages of satire and social commentary. The book had a profound impact on economic thought, and ever since it was published there has been debate over its meaning.

Keynes and classical economics

Keynes begins the General Theory with a summary of the classical theory of employment, which he encapsulates in his formulation of Say's Law as the dictum "Supply creates its own demand".

Under the classical theory, the wage rate is determined by the marginal productivity of labour, and as many people are employed as are willing to work at that rate. Unemployment may arise through friction or may be "voluntary," in the sense that it arises from a refusal to accept employment owing to "legislation or social practices ... or mere human obstinacy", but "...the classical postulates do not admit of the possibility of the third category," which Keynes defines as involuntary unemployment.

Keynes raises two objections to the classical theory's assumption that "wage bargains ... determine the real wage". The first lies in the fact that "labour stipulates (within limits) for a money-wage rather than a real wage". The second is that classical theory assumes that, "The real wages of labour depend on the wage bargains which labour makes with the entrepreneurs," whereas, "If money wages change, one would have expected the classical school to argue that prices would change in almost the same proportion, leaving the real wage and the level of unemployment practically the same as before." Keynes considers his second objection the more fundamental, but most commentators concentrate on his first one: it has been argued that the quantity theory of money protects the classical school from the conclusion Keynes expected from it.

Keynesian unemployment

Saving and investment

Saving is that part of income not devoted to consumption, and consumption is that part of expenditure not allocated to investment, i.e., to durable goods. Hence saving encompasses hoarding (the accumulation of income as cash) and the purchase of durable goods. The existence of net hoarding, or of a demand to hoard, is not admitted by the simplified liquidity preference model of the General Theory.

Once he rejects the classical theory that unemployment is due to excessive wages, Keynes proposes an alternative based on the relationship between saving and investment. In his view, unemployment arises whenever entrepreneurs' incentive to invest fails to keep pace with society's propensity to save (propensity is one of Keynes's synonyms for "demand"). The levels of saving and investment are necessarily equal, and income is therefore held down to a level where the desire to save is no greater than the incentive to invest.

The incentive to invest arises from the interplay between the physical circumstances of production and psychological anticipations of future profitability; but once these things are given the incentive is independent of income and depends solely on the rate of interest r. Keynes designates its value as a function of r as the "schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital".

The propensity to save behaves quite differently. Saving is simply that part of income not devoted to consumption, and:

... the prevailing psychological law seems to be that when aggregate income increases, consumption expenditure will also increase but to a somewhat lesser extent.

Keynes adds that "this psychological law was of the utmost importance in the development of my own thought".

Liquidity preference

Keynes viewed the money supply as one of the main determinants of the state of the real economy. The significance he attributed to it is one of the innovative features of his work, and was influential on the politically hostile monetarist school.

Money supply comes into play through the liquidity preference function, which is the demand function that corresponds to money supply. It specifies the amount of money people will seek to hold according to the state of the economy. In Keynes's first (and simplest) account – that of Chapter 13 – liquidity preference is determined solely by the interest rate r—which is seen as the earnings forgone by holding wealth in liquid form: hence liquidity preference can be written L(r ) and in equilibrium must equal the externally fixed money supply M̂.

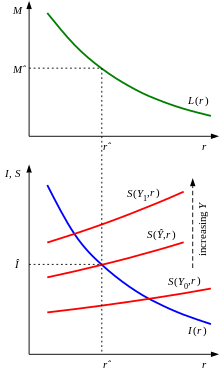

Keynes’s economic model

Money supply, saving and investment combine to determine the level of income as illustrated in the diagram, where the top graph shows money supply (on the vertical axis) against interest rate. M̂ determines the ruling interest rate r̂ through the liquidity preference function. The rate of interest determines the level of investment Î through the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital, shown as a blue curve in the lower graph. The red curves in the same diagram show what the propensities to save are for different incomes Y ; and the income Ŷ corresponding to the equilibrium state of the economy must be the one for which the implied level of saving at the established interest rate is equal to Î.

In Keynes's more complicated liquidity preference theory (presented in Chapter 15) the demand for money depends on income as well as on the interest rate and the analysis becomes more complicated. Keynes never fully integrated his second liquidity preference doctrine with the rest of his theory, leaving that to John Hicks: see the IS-LM model below.

Wage rigidity

Keynes rejects the classical explanation of unemployment based on wage rigidity, but it is not clear what effect the wage rate has on unemployment in his system. He treats wages of all workers as proportional to a single rate set by collective bargaining, and chooses his units so that this rate never appears separately in his discussion. It is present implicitly in those quantities he expresses in wage units, while being absent from those he expresses in money terms. It is therefore difficult to see whether, and in what way, his results differ for a different wage rate, nor is it clear what he thought about the matter.

Remedies for unemployment

Monetary remedies

An increase in the money supply, according to Keynes's theory, leads to a drop in the interest rate and an increase in the amount of investment that can be undertaken profitably, bringing with it an increase in total income.

Fiscal remedies

Keynes' name is associated with fiscal, rather than monetary, measures but they receive only passing (and often satirical) reference in the General Theory. He mentions "increased public works" as an example of something that brings employment through the multiplier, but this is before he develops the relevant theory, and he does not follow up when he gets to the theory.

Later in the same chapter he tells us that:

Ancient Egypt was doubly fortunate, and doubtless owed to this its fabled wealth, in that it possessed two activities, namely, pyramid-building as well as the search for the precious metals, the fruits of which, since they could not serve the needs of man by being consumed, did not stale with abundance. The Middle Ages built cathedrals and sang dirges. Two pyramids, two masses for the dead, are twice as good as one; but not so two railways from London to York.

But again, he doesn't get back to his implied recommendation to engage in public works, even if not fully justified from their direct benefits, when he constructs the theory. On the contrary he later advises us that ...

... our final task might be to select those variables which can be deliberately controlled or managed by central authority in the kind of system in which we actually live ...

and this appears to look forward to a future publication rather than to a subsequent chapter of the General Theory.

Keynesian models and concepts

Aggregate demand

Keynes' view of saving and investment was his most important departure from the classical outlook. It can be illustrated using the "Keynesian cross" devised by Paul Samuelson. The horizontal axis denotes total income and the purple curve shows C (Y ), the propensity to consume, whose complement S (Y ) is the propensity to save: the sum of these two functions is equal to total income, which is shown by the broken line at 45°.

The horizontal blue line I (r ) is the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital whose value is independent of Y. The schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital is dependent on the interest rate, specifically the interest rate cost of a new investment. If the interest rate charged by the financial sector to the productive sector is below the marginal efficiency of capital at that level of technology and capital intensity then investment is positive and grows the lower the interest rate is, given the diminishing return of capital. If the interest rate is above the marginal efficiency of capital then investment is equal to zero. Keynes interprets this as the demand for investment and denotes the sum of demands for consumption and investment as "aggregate demand", plotted as a separate curve. Aggregate demand must equal total income, so equilibrium income must be determined by the point where the aggregate demand curve crosses the 45° line. This is the same horizontal position as the intersection of I (r ) with S (Y ).

The equation I (r ) = S (Y ) had been accepted by the classics, who had viewed it as the condition of equilibrium between supply and demand for investment funds and as determining the interest rate (see the classical theory of interest). But insofar as they had had a concept of aggregate demand, they had seen the demand for investment as being given by S (Y ), since for them saving was simply the indirect purchase of capital goods, with the result that aggregate demand was equal to total income as an identity rather than as an equilibrium condition. Keynes takes note of this view in Chapter 2, where he finds it present in the early writings of Alfred Marshall but adds that "the doctrine is never stated to-day in this crude form".

The equation I (r ) = S (Y ) is accepted by Keynes for some or all of the following reasons:

- As a consequence of the principle of effective demand, which asserts that aggregate demand must equal total income (Chapter 3).

- As a consequence of the identity of saving with investment (Chapter 6) together with the equilibrium assumption that these quantities are equal to their demands.

- In agreement with the substance of the classical theory of the investment funds market, whose conclusion he considers the classics to have misinterpreted through circular reasoning (Chapter 14).

The Keynesian multiplier

Keynes introduces his discussion of the multiplier in Chapter 10 with a reference to Kahn's earlier paper (see below). He designates Kahn's multiplier the "employment multiplier" in distinction to his own "investment multiplier" and says that the two are only "a little different". Kahn's multiplier has consequently been understood by much of the Keynesian literature as playing a major role in Keynes's own theory, an interpretation encouraged by the difficulty of understanding Keynes's presentation. Kahn's multiplier gives the title ("The multiplier model") to the account of Keynesian theory in Samuelson's Economics and is almost as prominent in Alvin Hansen's Guide to Keynes and in Joan Robinson's Introduction to the Theory of Employment.

Keynes states that there is ...

... a confusion between the logical theory of the multiplier, which holds good continuously, without time-lag ... and the consequence of an expansion in the capital goods industries which take gradual effect, subject to a time-lag, and only after an interval ...

and implies that he is adopting the former theory. And when the multiplier eventually emerges as a component of Keynes's theory (in Chapter 18) it turns out to be simply a measure of the change of one variable in response to a change in another. The schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital is identified as one of the independent variables of the economic system: "What [it] tells us, is ... the point to which the output of new investment will be pushed ..." The multiplier then gives "the ratio ... between an increment of investment and the corresponding increment of aggregate income".

G. L. S. Shackle regarded Keynes' move away from Kahn's multiplier as ...

... a retrograde step ... For when we look upon the Multiplier as an instantaneous functional relation ... we are merely using the word Multiplier to stand for an alternative way of looking at the marginal propensity to consume ...

which G. M. Ambrosi cites as an instance of "a Keynesian commentator who would have liked Keynes to have written something less 'retrograde'".

The value Keynes assigns to his multiplier is the reciprocal of the marginal propensity to save: k = 1 / S '(Y ). This is the same as the formula for Kahn's mutliplier in a closed economy assuming that all saving (including the purchase of durable goods), and not just hoarding, constitutes leakage. Keynes gave his formula almost the status of a definition (it is put forward in advance of any explanation). His multiplier is indeed the value of "the ratio ... between an increment of investment and the corresponding increment of aggregate income" as Keynes derived it from his Chapter 13 model of liquidity preference, which implies that income must bear the entire effect of a change in investment. But under his Chapter 15 model a change in the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital has an effect shared between the interest rate and income in proportions depending on the partial derivatives of the liquidity preference function. Keynes did not investigate the question of whether his formula for multiplier needed revision.

The liquidity trap

The liquidity trap is a phenomenon that may impede the effectiveness of monetary policies in reducing unemployment.

Economists generally think the rate of interest will not fall below a certain limit, often seen as zero or a slightly negative number. Keynes suggested that the limit might be appreciably greater than zero but did not attach much practical significance to it. The term "liquidity trap" was coined by Dennis Robertson in his comments on the General Theory, but it was John Hicks in "Mr. Keynes and the Classics" who recognised the significance of a slightly different concept.

If the economy is in a position such that the liquidity preference curve is almost vertical, as must happen as the lower limit on r is approached, then a change in the money supply M̂ makes almost no difference to the equilibrium rate of interest r̂ or, unless there is compensating steepness in the other curves, to the resulting income Ŷ. As Hicks put it, "Monetary means will not force down the rate of interest any further."

Paul Krugman has worked extensively on the liquidity trap, claiming that it was the problem confronting the Japanese economy around the turn of the millennium. In his later words:

Short-term interest rates were close to zero, long-term rates were at historical lows, yet private investment spending remained insufficient to bring the economy out of deflation. In that environment, monetary policy was just as ineffective as Keynes described. Attempts by the Bank of Japan to increase the money supply simply added to already ample bank reserves and public holdings of cash...

The IS–LM model

Hicks showed how to analyze Keynes' system when liquidity preference is a function of income as well as of the rate of interest. Keynes's admission of income as an influence on the demand for money is a step back in the direction of classical theory, and Hicks takes a further step in the same direction by generalizing the propensity to save to take both Y and r as arguments. Less classically he extends this generalization to the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital.

The IS-LM model uses two equations to express Keynes' model. The first, now written I (Y, r ) = S (Y,r ), expresses the principle of effective demand. We may construct a graph on (Y, r ) coordinates and draw a line connecting those points satisfying the equation: this is the IS curve. In the same way we can write the equation of equilibrium between liquidity preference and the money supply as L(Y ,r ) = M̂ and draw a second curve – the LM curve – connecting points that satisfy it. The equilibrium values Ŷ of total income and r̂ of interest rate are then given by the point of intersection of the two curves.

If we follow Keynes's initial account under which liquidity preference depends only on the interest rate r, then the LM curve is horizontal.

Joan Robinson commented that:

... modern teaching has been confused by J. R. Hicks' attempt to reduce the General Theory to a version of static equilibrium with the formula IS–LM. Hicks has now repented and changed his name from J. R. to John, but it will take a long time for the effects of his teaching to wear off.

Hicks subsequently relapsed.

Keynesian economic policies

Active fiscal policy

Keynes argued that the solution to the Great Depression was to stimulate the country ("incentive to invest") through some combination of two approaches:

- A reduction in interest rates (monetary policy), and

- Government investment in infrastructure (fiscal policy).

If the interest rate at which businesses and consumers can borrow decreases, investments that were previously uneconomic become profitable, and large consumer sales normally financed through debt (such as houses, automobiles, and, historically, even appliances like refrigerators) become more affordable. A principal function of central banks in countries that have them is to influence this interest rate through a variety of mechanisms collectively called monetary policy. This is how monetary policy that reduces interest rates is thought to stimulate economic activity, i.e., "grow the economy"—and why it is called expansionary monetary policy.

Expansionary fiscal policy consists of increasing net public spending, which the government can effect by a) taxing less, b) spending more, or c) both. Investment and consumption by government raises demand for businesses' products and for employment, reversing the effects of the aforementioned imbalance. If desired spending exceeds revenue, the government finances the difference by borrowing from capital markets by issuing government bonds. This is called deficit spending. Two points are important to note at this point. First, deficits are not required for expansionary fiscal policy, and second, it is only change in net spending that can stimulate or depress the economy. For example, if a government ran a deficit of 10% both last year and this year, this would represent neutral fiscal policy. In fact, if it ran a deficit of 10% last year and 5% this year, this would actually be contractionary. On the other hand, if the government ran a surplus of 10% of GDP last year and 5% this year, that would be expansionary fiscal policy, despite never running a deficit at all.

But – contrary to some critical characterizations of it – Keynesianism does not consist solely of deficit spending, since it recommends adjusting fiscal policies according to cyclical circumstances. An example of a counter-cyclical policy is raising taxes to cool the economy and to prevent inflation when there is abundant demand-side growth, and engaging in deficit spending on labour-intensive infrastructure projects to stimulate employment and stabilize wages during economic downturns.

Keynes's ideas influenced Franklin D. Roosevelt's view that insufficient buying-power caused the Depression. During his presidency, Roosevelt adopted some aspects of Keynesian economics, especially after 1937, when, in the depths of the Depression, the United States suffered from recession yet again following fiscal contraction. But to many the true success of Keynesian policy can be seen at the onset of World War II, which provided a kick to the world economy, removed uncertainty, and forced the rebuilding of destroyed capital. Keynesian ideas became almost official in social-democratic Europe after the war and in the U.S. in the 1960s.

The Keynesian advocacy of deficit spending contrasted with the classical and neoclassical economic analysis of fiscal policy. They admitted that fiscal stimulus could actuate production. But, to these schools, there was no reason to believe that this stimulation would outrun the side-effects that "crowd out" private investment: first, it would increase the demand for labour and raise wages, hurting profitability; Second, a government deficit increases the stock of government bonds, reducing their market price and encouraging high interest rates, making it more expensive for business to finance fixed investment. Thus, efforts to stimulate the economy would be self-defeating.

The Keynesian response is that such fiscal policy is appropriate only when unemployment is persistently high, above the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU). In that case, crowding out is minimal. Further, private investment can be "crowded in": Fiscal stimulus raises the market for business output, raising cash flow and profitability, spurring business optimism. To Keynes, this accelerator effect meant that government and business could be complements rather than substitutes in this situation.

Second, as the stimulus occurs, gross domestic product rises—raising the amount of saving, helping to finance the increase in fixed investment. Finally, government outlays need not always be wasteful: government investment in public goods that is not provided by profit-seekers encourages the private sector's growth. That is, government spending on such things as basic research, public health, education, and infrastructure could help the long-term growth of potential output.

In Keynes's theory, there must be significant slack in the labour market before fiscal expansion is justified.

Keynesian economists believe that adding to profits and incomes during boom cycles through tax cuts, and removing income and profits from the economy through cuts in spending during downturns, tends to exacerbate the negative effects of the business cycle. This effect is especially pronounced when the government controls a large fraction of the economy, as increased tax revenue may aid investment in state enterprises in downturns, and decreased state revenue and investment harm those enterprises.

Views on trade imbalance

In the last few years of his life, John Maynard Keynes was much preoccupied with the question of balance in international trade. He was the leader of the British delegation to the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference in 1944 that established the Bretton Woods system of international currency management. He was the principal author of a proposal – the so-called Keynes Plan – for an International Clearing Union. The two governing principles of the plan were that the problem of settling outstanding balances should be solved by 'creating' additional 'international money', and that debtor and creditor should be treated almost alike as disturbers of equilibrium. In the event, though, the plans were rejected, in part because "American opinion was naturally reluctant to accept the principle of equality of treatment so novel in debtor-creditor relationships".

The new system is not founded on free trade (liberalisation of foreign trade) but rather on regulating international trade to eliminate trade imbalances. Nations with a surplus would have a powerful incentive to get rid of it, which would automatically clear other nations' deficits. Keynes proposed a global bank that would issue its own currency—the bancor—which was exchangeable with national currencies at fixed rates of exchange and would become the unit of account between nations, which means it would be used to measure a country's trade deficit or trade surplus. Every country would have an overdraft facility in its bancor account at the International Clearing Union. He pointed out that surpluses lead to weak global aggregate demand – countries running surpluses exert a "negative externality" on trading partners, and posed far more than those in deficit, a threat to global prosperity. Keynes thought that surplus countries should be taxed to avoid trade imbalances. In "National Self-Sufficiency" The Yale Review, Vol. 22, no. 4 (June 1933), he already highlighted the problems created by free trade.

His view, supported by many economists and commentators at the time, was that creditor nations may be just as responsible as debtor nations for disequilibrium in exchanges and that both should be under an obligation to bring trade back into a state of balance. Failure for them to do so could have serious consequences. In the words of Geoffrey Crowther, then editor of The Economist, "If the economic relationships between nations are not, by one means or another, brought fairly close to balance, then there is no set of financial arrangements that can rescue the world from the impoverishing results of chaos."

These ideas were informed by events prior to the Great Depression when – in the opinion of Keynes and others – international lending, primarily by the U.S., exceeded the capacity of sound investment and so got diverted into non-productive and speculative uses, which in turn invited default and a sudden stop to the process of lending.

Influenced by Keynes, economic texts in the immediate post-war period put a significant emphasis on balance in trade. For example, the second edition of the popular introductory textbook, An Outline of Money, devoted the last three of its ten chapters to questions of foreign exchange management and in particular the 'problem of balance'. However, in more recent years, since the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, with the increasing influence of Monetarist schools of thought in the 1980s, and particularly in the face of large sustained trade imbalances, these concerns – and particularly concerns about the destabilising effects of large trade surpluses – have largely disappeared from mainstream economics discourse and Keynes' insights have slipped from view. They are receiving some attention again in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007–08.

Postwar Keynesianism

Keynes's ideas became widely accepted after World War II, and until the early 1970s, Keynesian economics provided the main inspiration for economic policy makers in Western industrialized countries. Governments prepared high quality economic statistics on an ongoing basis and tried to base their policies on the Keynesian theory that had become the norm. In the early era of social liberalism and social democracy, most western capitalist countries enjoyed low, stable unemployment and modest inflation, an era called the Golden Age of Capitalism.

In terms of policy, the twin tools of post-war Keynesian economics were fiscal policy and monetary policy. While these are credited to Keynes, others, such as economic historian David Colander, argue that they are, rather, due to the interpretation of Keynes by Abba Lerner in his theory of functional finance, and should instead be called "Lernerian" rather than "Keynesian".

Through the 1950s, moderate degrees of government demand leading industrial development, and use of fiscal and monetary counter-cyclical policies continued, and reached a peak in the "go go" 1960s, where it seemed to many Keynesians that prosperity was now permanent. In 1971, Republican US President Richard Nixon even proclaimed "I am now a Keynesian in economics."

Beginning in the late 1960s, a new classical macroeconomics movement arose, critical of Keynesian assumptions, and seemed, especially in the 1970s, to explain certain phenomena better. It was characterized by explicit and rigorous adherence to microfoundations, as well as use of increasingly sophisticated mathematical modelling.

With the oil shock of 1973, and the economic problems of the 1970s, Keynesian economics began to fall out of favour. During this time, many economies experienced high and rising unemployment, coupled with high and rising inflation, contradicting the Phillips curve's prediction. This stagflation meant that the simultaneous application of expansionary (anti-recession) and contractionary (anti-inflation) policies appeared necessary. This dilemma led to the end of the Keynesian near-consensus of the 1960s, and the rise throughout the 1970s of ideas based upon more classical analysis, including monetarism, supply-side economics, and new classical economics.

However, by the late 1980s, certain failures of the new classical models, both theoretical (see Real business cycle theory) and empirical (see the "Volcker recession") hastened the emergence of New Keynesian economics, a school that sought to unite the most realistic aspects of Keynesian and neo-classical assumptions and place them on more rigorous theoretical foundation than ever before.

One line of thinking, utilized also as a critique of the notably high unemployment and potentially disappointing GNP growth rates associated with the new classical models by the mid-1980s, was to emphasize low unemployment and maximal economic growth at the cost of somewhat higher inflation (its consequences kept in check by indexing and other methods, and its overall rate kept lower and steadier by such potential policies as Martin Weitzman's share economy).

Schools

Multiple schools of economic thought that trace their legacy to Keynes currently exist, the notable ones being neo-Keynesian economics, New Keynesian economics, post-Keynesian economics, and the new neoclassical synthesis. Keynes's biographer Robert Skidelsky writes that the post-Keynesian school has remained closest to the spirit of Keynes's work in following his monetary theory and rejecting the neutrality of money. Today these ideas, regardless of provenance, are referred to in academia under the rubric of "Keynesian economics", due to Keynes's role in consolidating, elaborating, and popularizing them.

In the postwar era, Keynesian analysis was combined with neoclassical economics to produce what is generally termed the "neoclassical synthesis", yielding neo-Keynesian economics, which dominated mainstream macroeconomic thought. Though it was widely held that there was no strong automatic tendency to full employment, many believed that if government policy were used to ensure it, the economy would behave as neoclassical theory predicted. This post-war domination by neo-Keynesian economics was broken during the stagflation of the 1970s. There was a lack of consensus among macroeconomists in the 1980s, and during this period New Keynesian economics was developed, ultimately becoming- along with new classical macroeconomics- a part of the current consensus, known as the new neoclassical synthesis.

Post-Keynesian economists, on the other hand, reject the neoclassical synthesis and, in general, neoclassical economics applied to the macroeconomy. Post-Keynesian economics is a heterodox school that holds that both neo-Keynesian economics and New Keynesian economics are incorrect, and a misinterpretation of Keynes's ideas. The post-Keynesian school encompasses a variety of perspectives, but has been far less influential than the other more mainstream Keynesian schools.

Interpretations of Keynes have emphasized his stress on the international coordination of Keynesian policies, the need for international economic institutions, and the ways in which economic forces could lead to war or could promote peace.

Keynesianism and liberalism

In a 2014 paper, economist Alan Blinder argues that, "for not very good reasons," public opinion in the United States has associated Keynesianism with liberalism, and he states that such is incorrect. For example, both Presidents Ronald Reagan (1981-89) and George W. Bush (2001-09) supported policies that were, in fact, Keynesian, even though both men were conservative leaders. And tax cuts can provide highly helpful fiscal stimulus during a recession, just as much as infrastructure spending can. Blinder concludes, "If you are not teaching your students that 'Keynesianism' is neither conservative nor liberal, you should be."

Other schools of macroeconomic thought

The Keynesian schools of economics are situated alongside a number of other schools that have the same perspectives on what the economic issues are, but differ on what causes them and how best to resolve them. Today, most of these schools of thought have been subsumed into modern macroeconomic theory.

Stockholm School

The Stockholm school rose to prominence at about the same time that Keynes published his General Theory and shared a common concern in business cycles and unemployment. The second generation of Swedish economists also advocated government intervention through spending during economic downturns although opinions are divided over whether they conceived the essence of Keynes's theory before he did.

Monetarism

There was debate between monetarists and Keynesians in the 1960s over the role of government in stabilizing the economy. Both monetarists and Keynesians agree that issues such as business cycles, unemployment, and deflation are caused by inadequate demand. However, they had fundamentally different perspectives on the capacity of the economy to find its own equilibrium, and the degree of government intervention that would be appropriate. Keynesians emphasized the use of discretionary fiscal policy and monetary policy, while monetarists argued the primacy of monetary policy, and that it should be rules-based.

The debate was largely resolved in the 1980s. Since then, economists have largely agreed that central banks should bear the primary responsibility for stabilizing the economy, and that monetary policy should largely follow the Taylor rule – which many economists credit with the Great Moderation. The financial crisis of 2007–08, however, has convinced many economists and governments of the need for fiscal interventions and highlighted the difficulty in stimulating economies through monetary policy alone during a liquidity trap.

Marxian economics

Some Marxist economists criticized Keynesian economics. For example, in his 1946 appraisal Paul Sweezy—while admitting that there was much in the General Theory's analysis of effective demand that Marxists could draw on—described Keynes as a prisoner of his neoclassical upbringing. Sweezy argued that Keynes had never been able to view the capitalist system as a totality. He argued that Keynes regarded the class struggle carelessly, and overlooked the class role of the capitalist state, which he treated as a deus ex machina, and some other points. While Michał Kalecki was generally enthusiastic about the Keynesian revolution, he predicted that it would not endure, in his article "Political Aspects of Full Employment". In the article Kalecki predicted that the full employment delivered by Keynesian policy would eventually lead to a more assertive working class and weakening of the social position of business leaders, causing the elite to use their political power to force the displacement of the Keynesian policy even though profits would be higher than under a laissez faire system: The erosion of social prestige and political power would be unacceptable to the elites despite higher profits.

Public choice

James M. Buchanan criticized Keynesian economics on the grounds that governments would in practice be unlikely to implement theoretically optimal policies. The implicit assumption underlying the Keynesian fiscal revolution, according to Buchanan, was that economic policy would be made by wise men, acting without regard to political pressures or opportunities, and guided by disinterested economic technocrats. He argued that this was an unrealistic assumption about political, bureaucratic and electoral behaviour. Buchanan blamed Keynesian economics for what he considered a decline in America's fiscal discipline. Buchanan argued that deficit spending would evolve into a permanent disconnect between spending and revenue, precisely because it brings short-term gains, so, ending up institutionalizing irresponsibility in the federal government, the largest and most central institution in our society. Martin Feldstein argues that the legacy of Keynesian economics–the misdiagnosis of unemployment, the fear of saving, and the unjustified government intervention–affected the fundamental ideas of policy makers. Milton Friedman thought that Keynes's political bequest was harmful for two reasons. First, he thought whatever the economic analysis, benevolent dictatorship is likely sooner or later to lead to a totalitarian society. Second, he thought Keynes's economic theories appealed to a group far broader than economists primarily because of their link to his political approach. Alex Tabarrok argues that Keynesian politics–as distinct from Keynesian policies–has failed pretty much whenever it's been tried, at least in liberal democracies.

In response to this argument, John Quiggin, wrote about these theories' implication for a liberal democratic order. He thought that if it is generally accepted that democratic politics is nothing more than a battleground for competing interest groups, then reality will come to resemble the model. Paul Krugman wrote "I don’t think we need to take that as an immutable fact of life; but still, what are the alternatives?" Daniel Kuehn, criticized James M. Buchanan. He argued, "if you have a problem with politicians - criticize politicians," not Keynes. He also argued that empirical evidence makes it pretty clear that Buchanan was wrong. James Tobin argued, if advising government officials, politicians, voters, it's not for economists to play games with them. Keynes implicitly rejected this argument, in "soon or late it is ideas not vested interests which are dangerous for good or evil."

Brad DeLong has argued that politics is the main motivator behind objections to the view that government should try to serve a stabilizing macroeconomic role. Paul Krugman argued that a regime that by and large lets markets work, but in which the government is ready both to rein in excesses and fight slumps is inherently unstable, due to intellectual instability, political instability, and financial instability.

New classical

Another influential school of thought was based on the Lucas critique of Keynesian economics. This called for greater consistency with microeconomic theory and rationality, and in particular emphasized the idea of rational expectations. Lucas and others argued that Keynesian economics required remarkably foolish and short-sighted behaviour from people, which totally contradicted the economic understanding of their behaviour at a micro level. New classical economics introduced a set of macroeconomic theories that were based on optimizing microeconomic behaviour. These models have been developed into the real business-cycle theory, which argues that business cycle fluctuations can to a large extent be accounted for by real (in contrast to nominal) shocks.

Beginning in the late 1950s new classical macroeconomists began to disagree with the methodology employed by Keynes and his successors. Keynesians emphasized the dependence of consumption on disposable income and, also, of investment on current profits and current cash flow. In addition, Keynesians posited a Phillips curve that tied nominal wage inflation to unemployment rate. To support these theories, Keynesians typically traced the logical foundations of their model (using introspection) and supported their assumptions with statistical evidence. New classical theorists demanded that macroeconomics be grounded on the same foundations as microeconomic theory, profit-maximizing firms and rational, utility-maximizing consumers.

The result of this shift in methodology produced several important divergences from Keynesian macroeconomics:

- Independence of consumption and current income (life-cycle permanent income hypothesis)

- Irrelevance of current profits to investment (Modigliani–Miller theorem)

- Long run independence of inflation and unemployment (natural rate of unemployment)

- The inability of monetary policy to stabilize output (rational expectations)

- Irrelevance of taxes and budget deficits to consumption (Ricardian equivalence)