A cosmological argument, in natural theology, is an argument which claims that the existence of God can be inferred from facts concerning causation, explanation, change, motion, contingency, dependency, or finitude with respect to the universe or some totality of objects. A cosmological argument can also sometimes be referred to as an argument from universal causation, an argument from first cause, or the causal argument. Whichever term is employed, there are two basic variants of the argument, each with subtle yet important distinctions: in esse (essentiality), and in fieri (becoming).

The basic premises of all of these arguments involve the concept of causation. The conclusion of these arguments is that there exists a first cause (for whichever group of things it is being argued has a cause), subsequently deemed to be God. The history of this argument goes back to Aristotle or earlier, was developed in Neoplatonism and early Christianity and later in medieval Islamic theology during the 9th to 12th centuries, and was re-introduced to medieval Christian theology in the 13th century by Thomas Aquinas. The cosmological argument is closely related to the principle of sufficient reason as addressed by Gottfried Leibniz and Samuel Clarke, itself a modern exposition of the claim that "nothing comes from nothing" attributed to Parmenides.

Contemporary defenders of cosmological arguments include William Lane Craig, Robert Koons, and Alexander Pruss.

History

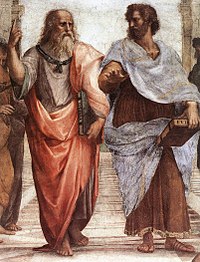

Plato (c. 427–347 BC) and Aristotle (c. 384–322 BC) both posited first cause arguments, though each had certain notable caveats. In The Laws (Book X), Plato posited that all movement in the world and the Cosmos was "imparted motion". This required a "self-originated motion" to set it in motion and to maintain it. In Timaeus, Plato posited a "demiurge" of supreme wisdom and intelligence as the creator of the Cosmos.

Aristotle argued against the idea of a first cause, often confused with the idea of a "prime mover" or "unmoved mover" (πρῶτον κινοῦν ἀκίνητον or primus motor) in his Physics and Metaphysics. Aristotle argued in favor of the idea of several unmoved movers, one powering each celestial sphere, which he believed lived beyond the sphere of the fixed stars, and explained why motion in the universe (which he believed was eternal) had continued for an infinite period of time. Aristotle argued the atomist's assertion of a non-eternal universe would require a first uncaused cause – in his terminology, an efficient first cause – an idea he considered a nonsensical flaw in the reasoning of the atomists.

Like Plato, Aristotle believed in an eternal cosmos with no beginning and no end (which in turn follows Parmenides' famous statement that "nothing comes from nothing"). In what he called "first philosophy" or metaphysics, Aristotle did intend a theological correspondence between the prime mover and deity (presumably Zeus); functionally, however, he provided an explanation for the apparent motion of the "fixed stars" (now understood as the daily rotation of the Earth). According to his theses, immaterial unmoved movers are eternal unchangeable beings that constantly think about thinking, but being immaterial, they are incapable of interacting with the cosmos and have no knowledge of what transpires therein. From an "aspiration or desire", the celestial spheres, imitate that purely intellectual activity as best they can, by uniform circular motion. The unmoved movers inspiring the planetary spheres are no different in kind from the prime mover, they merely suffer a dependency of relation to the prime mover. Correspondingly, the motions of the planets are subordinate to the motion inspired by the prime mover in the sphere of fixed stars. Aristotle's natural theology admitted no creation or capriciousness from the immortal pantheon, but maintained a defense against dangerous charges of impiety.

Plotinus, a third-century Platonist, taught that the One transcendent absolute caused the universe to exist simply as a consequence of its existence (creatio ex deo). His disciple Proclus stated "The One is God".

Centuries later, the Islamic philosopher Avicenna (c. 980–1037) inquired into the question of being, in which he distinguished between essence (Mahiat) and existence (Wujud). He argued that the fact of existence could not be inferred from or accounted for by the essence of existing things, and that form and matter by themselves could not originate and interact with the movement of the Universe or the progressive actualization of existing things. Thus, he reasoned that existence must be due to an agent cause that necessitates, imparts, gives, or adds existence to an essence. To do so, the cause must coexist with its effect and be an existing thing.

Steven Duncan writes that it "was first formulated by a Greek-speaking Syriac Christian neo-Platonist, John Philoponus, who claims to find a contradiction between the Greek pagan insistence on the eternity of the world and the Aristotelian rejection of the existence of any actual infinite". Referring to the argument as the "'Kalam' cosmological argument", Duncan asserts that it "received its fullest articulation at the hands of [medieval] Muslim and Jewish exponents of Kalam ("the use of reason by believers to justify the basic metaphysical presuppositions of the faith").

Thomas Aquinas (c. 1225–1274) adapted and enhanced the argument he found in his reading of Aristotle and Avicenna to form one of the most influential versions of the cosmological argument. His conception of First Cause was the idea that the Universe must be caused by something that is itself uncaused, which he claimed is that which we call God:

The second way is from the nature of the efficient cause. In the world of sense we find there is an order of efficient causes. There is no case known (neither is it, indeed, possible) in which a thing is found to be the efficient cause of itself; for so it would be prior to itself, which is impossible. Now in efficient causes it is not possible to go on to infinity, because in all efficient causes following in order, the first is the cause of the intermediate cause, and the intermediate is the cause of the ultimate cause, whether the intermediate cause be several, or only one. Now to take away the cause is to take away the effect. Therefore, if there be no first cause among efficient causes, there will be no ultimate, nor any intermediate cause. But if in efficient causes it is possible to go on to infinity, there will be no first efficient cause, neither will there be an ultimate effect, nor any intermediate efficient causes; all of which is plainly false. Therefore it is necessary to admit a first efficient cause, to which everyone gives the name of God.

Importantly, Aquinas' Five Ways, given the second question of his Summa Theologica, are not the entirety of Aquinas' demonstration that the Christian God exists. The Five Ways form only the beginning of Aquinas' Treatise on the Divine Nature.

Versions of the argument

Argument from contingency

In the scholastic era, Aquinas formulated the "argument from contingency", following Aristotle in claiming that there must be something to explain why the Universe exists. Since the Universe could, under different circumstances, conceivably not exist (contingency), its existence must have a cause – not merely another contingent thing, but something that exists by necessity (something that must exist in order for anything else to exist). In other words, even if the Universe has always existed, it still owes its existence to an uncaused cause, Aquinas further said: "... and this we understand to be God."

Aquinas's argument from contingency allows for the possibility of a Universe that has no beginning in time. It is a form of argument from universal causation. Aquinas observed that, in nature, there were things with contingent existences. Since it is possible for such things not to exist, there must be some time at which these things did not in fact exist. Thus, according to Aquinas, there must have been a time when nothing existed. If this is so, there would exist nothing that could bring anything into existence. Contingent beings, therefore, are insufficient to account for the existence of contingent beings: there must exist a necessary being whose non-existence is an impossibility, and from which the existence of all contingent beings is ultimately derived.

The German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz made a similar argument with his principle of sufficient reason in 1714. "There can be found no fact that is true or existent, or any true proposition," he wrote, "without there being a sufficient reason for its being so and not otherwise, although we cannot know these reasons in most cases." He formulated the cosmological argument succinctly: "Why is there something rather than nothing? The sufficient reason ... is found in a substance which ... is a necessary being bearing the reason for its existence within itself."

Leibniz's argument from contingency is one of the most popular cosmological arguments in philosophy of religion. It attempts to prove the existence of a necessary being and infer that this being is God. Alexander Pruss formulates the argument as follows:

- Every contingent fact has an explanation.

- There is a contingent fact that includes all other contingent facts.

- Therefore, there is an explanation of this fact.

- This explanation must involve a necessary being.

- This necessary being is God.

Premise 1 is a form of the principle of sufficient reason stating that all contingently true sentences (i.e. contingent facts) have a sufficient explanation as to why they are the case. Premise 2 refers to what is known as the Big Conjunctive Contingent Fact (abbreviated BCCF), and the BCCF is generally taken to be the logical conjunction of all contingent facts. It can be thought about as the sum total of all contingent reality. Premise 3 then concludes that the BCCF has an explanation, as every contingency does (in virtue of the PSR). It follows that this explanation is non-contingent (i.e. necessary); no contingency can explain the BCCF, because every contingent fact is a part of the BCCF. Statement 5, which is either seen as a premise or a conclusion, infers that the necessary being which explains the totality of contingent facts is God. Several philosophers of religion, such as Joshua Rasmussen and T. Ryan Byerly, have argued for the inference from (4) to (5).

In esse and in fieri

The difference between the arguments from causation in fieri and in esse is a fairly important one. In fieri is generally translated as "becoming", while in esse is generally translated as "in essence". In fieri, the process of becoming, is similar to building a house. Once it is built, the builder walks away, and it stands on its own accord; compare the watchmaker analogy. (It may require occasional maintenance, but that is beyond the scope of the first cause argument.)

In esse (essence) is more akin to the light from a candle or the liquid in a vessel. George Hayward Joyce, SJ, explained that, "where the light of the candle is dependent on the candle's continued existence, not only does a candle produce light in a room in the first instance, but its continued presence is necessary if the illumination is to continue. If it is removed, the light ceases. Again, a liquid receives its shape from the vessel in which it is contained; but were the pressure of the containing sides withdrawn, it would not retain its form for an instant." This form of the argument is far more difficult to separate from a purely first cause argument than is the example of the house's maintenance above, because here the First Cause is insufficient without the candle's or vessel's continued existence.

The philosopher Robert Koons has stated a new variant on the cosmological argument. He says that to deny causation is to deny all empirical ideas – for example, if we know our own hand, we know it because of the chain of causes including light being reflected upon one's eyes, stimulating the retina and sending a message through the optic nerve into your brain. He summarised the purpose of the argument as "that if you don't buy into theistic metaphysics, you're undermining empirical science. The two grew up together historically and are culturally and philosophically inter-dependent ... If you say I just don't buy this causality principle – that's going to be a big big problem for empirical science." This in fieri version of the argument therefore does not intend to prove God, but only to disprove objections involving science, and the idea that contemporary knowledge disproves the cosmological argument.

Kalām cosmological argument

William Lane Craig, who was responsible for re-popularizing this argument in Western philosophy, presents it in the following general form:

- Whatever begins to exist has a cause of its existence.

- The universe began to exist.

- Therefore, the universe has a cause of its existence.

Craig explains, by nature of the event (the Universe coming into existence), attributes unique to (the concept of) God must also be attributed to the cause of this event, including but not limited to: enormous power (if not omnipotence), being the creator of the Heavens and the Earth (as God is according to the Christian understanding of God), being eternal and being absolutely self-sufficient. Since these attributes are unique to God, anything with these attributes must be God. Something does have these attributes: the cause; hence, the cause is God, the cause exists; hence, God exists.

Craig defends the second premise, that the Universe had a beginning starting with Al-Ghazali's proof that an actual infinity is impossible. However, If the universe never had a beginning then there would be an actual infinite, Craig claims, namely an infinite amount of cause and effect events. Hence, the Universe had a beginning.

Metaphysical argument for the existence of God

Duns Scotus, the influential Medieval Christian theologian, created a metaphysical argument for the existence of God. Though it was inspired by Aquinas' argument from motion, he, like other philosophers and theologians, believed that his statement for God's existence could be considered separate to Aquinas'. His explanation for God's existence is long, and can be summarised as follows:

- Something can be produced.

- It is produced by itself, something or another.

- Not by nothing, because nothing causes nothing.

- Not by itself, because an effect never causes itself.

- Therefore, by another A.

- If A is first then we have reached the conclusion.

- If A is not first, then we return to 2).

- From 3) and 4), we produce another- B. The ascending series is either infinite or finite.

- An infinite series is not possible.

- Therefore, God exists.

Scotus deals immediately with two objections he can see: first, that there cannot be a first, and second, that the argument falls apart when 1) is questioned. He states that infinite regress is impossible, because it provokes unanswerable questions, like, in modern English, "What is infinity minus infinity?" The second he states can be answered if the question is rephrased using modal logic, meaning that the first statement is instead "It is possible that something can be produced."

Cosmological argument and infinite regress

Depending on its formulation, the cosmological argument is an example of a positive infinite regress argument. An infinite regress is an infinite series of entities governed by a recursive principle that determines how each entity in the series depends on or is produced by its predecessor. An infinite regress argument is an argument against a theory based on the fact that this theory leads to an infinite regress. A positive infinite regress argument employs the regress in question to argue in support of a theory by showing that its alternative involves a vicious regress. The regress relevant for the cosmological argument is the regress of causes: an event occurred because it was caused by another event that occurred before it, which was itself caused by a previous event, and so on. For an infinite regress argument to be successful, it has to demonstrate not just that the theory in question entails an infinite regress but also that this regress is vicious. Once the viciousness of the regress of causes is established, the cosmological argument can proceed to its positive conclusion by holding that it is necessary to posit a first cause in order to avoid it.

A regress can be vicious due to metaphysical impossibility, implausibility or explanatory failure. It is sometimes held that the regress of causes is vicious because it is metaphysically impossible, i.e. that it involves an outright contradiction. But it is difficult to see where this contradiction lies unless an additional assumption is accepted: that actual infinity is impossible. But this position is opposed to infinity in general, not just specifically to the regress of causes. A more promising view is that the regress of causes is to be rejected because it is implausible. Such an argument can be based on empirical observation, e.g. that, to the best of our knowledge, our universe had a beginning in the form of the Big Bang. But it can also be based on more abstract principles, like Ockham's razor, which posits that we should avoid ontological extravagance by not multiplying entities without necessity. A third option is to see the regress of causes as vicious due to explanatory failure, i.e. that it does not solve the problem it was formulated to solve or that it assumes already in disguised form what it was supposed to explain. According to this position, we seek to explain one event in the present by citing an earlier event that caused it. But this explanation is incomplete unless we can come to understand why this earlier event occurred, which is itself explained by its own cause and so on. At each step, the occurrence of an event has to be assumed. So it fails to explain why anything at all occurs, why there is a chain of causes to begin with.

Objections and counterarguments

What caused the First Cause?

One objection to the argument is that it leaves open the question of why the First Cause is unique in that it does not require any causes. Proponents argue that the First Cause is exempt from having a cause, while opponents argue that this is special pleading or otherwise untrue. Critics often press that arguing for the First Cause's exemption raises the question of why the First Cause is indeed exempt, whereas defenders maintain that this question has been answered by the various arguments, emphasizing that none of its major forms rest on the premise that everything has a cause.

William Lane Craig, who popularised and is notable for defending the Kalam cosmological argument, argues that the infinite is impossible, whichever perspective the viewer takes, and so there must always have been one unmoved thing to begin the universe. He uses Hilbert's paradox of the Grand Hotel and the question 'What is infinity minus infinity?' to illustrate the idea that the infinite is metaphysically, mathematically, and even conceptually, impossible. Other reasons include the fact that it is impossible to count down from infinity, and that, had the universe existed for an infinite amount of time, every possible event, including the final end of the universe, would already have occurred. He therefore states his argument in three points- firstly, everything that begins to exist has a cause of its existence; secondly, the universe began to exist; so, thirdly, therefore, the universe has a cause of its existence. Craig argues in the Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology that there cannot be an infinite regress of causes and thus there must be a first uncaused cause, even if one posits a plurality of causes of the universe. He argues Occam's Razor may be employed to remove unneeded further causes of the universe, to leave a single uncaused cause.

Secondly, it is argued that the premise of causality has been arrived at via a posteriori (inductive) reasoning, which is dependent on experience. David Hume highlighted this problem of induction and argued that causal relations were not true a priori. However, as to whether inductive or deductive reasoning is more valuable remains a matter of debate, with the general conclusion being that neither is prominent. Opponents of the argument tend to argue that it is unwise to draw conclusions from an extrapolation of causality beyond experience. Andrew Loke replies that, according to the Kalam Cosmological Argument, only things which begin to exist require a cause. On the other hand, something that is without beginning has always existed and therefore does not require a cause. The Cosmological Argument posits that there cannot be an actual infinite regress of causes, therefore there must be an uncaused First Cause that is beginningless and does not require a cause.

Not evidence for a theistic God

The basic cosmological argument merely establishes that a First Cause exists, not that it has the attributes of a theistic god, such as omniscience, omnipotence, and omnibenevolence. This is why the argument is often expanded to show that at least some of these attributes are necessarily true, for instance in the modern Kalam argument given above.

Existence of causal loops

A causal loop is a form of predestination paradox arising where traveling backwards in time is deemed a possibility. A sufficiently powerful entity in such a world would have the capacity to travel backwards in time to a point before its own existence, and to then create itself, thereby initiating everything which follows from it.

The usual reason given to refute the possibility of a causal loop is that it requires that the loop as a whole be its own cause. Richard Hanley argues that causal loops are not logically, physically, or epistemically impossible: "[In timed systems,] the only possibly objectionable feature that all causal loops share is that coincidence is required to explain them." However, Andrew Loke argues that causal loop of the type that is supposed to avoid a First Cause suffers from the problem of vicious circularity and thus it would not work.

Existence of infinite causal chains

David Hume and later Paul Edwards have invoked a similar principle in their criticisms of the cosmological argument. William L. Rowe has called this the Hume-Edwards principle:

If the existence of every member of a set is explained, the existence of that set is thereby explained.

Nevertheless, David White argues that the notion of an infinite causal regress providing a proper explanation is fallacious. Furthermore, in Hume's Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, the character Demea states that even if the succession of causes is infinite, the whole chain still requires a cause. To explain this, suppose there exists a causal chain of infinite contingent beings. If one asks the question, "Why are there any contingent beings at all?", it does not help to be told that "There are contingent beings because other contingent beings caused them." That answer would just presuppose additional contingent beings. An adequate explanation of why some contingent beings exist would invoke a different sort of being, a necessary being that is not contingent. A response might suppose each individual is contingent but the infinite chain as a whole is not; or the whole infinite causal chain to be its own cause.

Severinsen argues that there is an "infinite" and complex causal structure. White tried to introduce an argument "without appeal to the principle of sufficient reason and without denying the possibility of an infinite causal regress". A number of other arguments have been offered to demonstrate that an actual infinite regress cannot exist, viz. the argument for the impossibility of concrete actual infinities, the argument for the impossibility of traversing an actual infinite, the argument from the lack of capacity to begin to exist, and various arguments from paradoxes.

Big Bang cosmology

Some cosmologists and physicists argue that a challenge to the cosmological argument is the nature of time: "One finds that time just disappears from the Wheeler–DeWitt equation" (Carlo Rovelli). The Big Bang theory states that it is the point in which all dimensions came into existence, the start of both space and time. Then, the question "What was there before the Universe?" makes no sense; the concept of "before" becomes meaningless when considering a situation without time. This has been put forward by J. Richard Gott III, James E. Gunn, David N. Schramm, and Beatrice Tinsley, who said that asking what occurred before the Big Bang is like asking what is north of the North Pole. However, some cosmologists and physicists do attempt to investigate causes for the Big Bang, using such scenarios as the collision of membranes.

Philosopher Edward Feser argues that most of the classical philosophers' cosmological arguments for the existence of God do not depend on the Big Bang or whether the universe had a beginning. The question is not about what got things started or how long they have been going, but rather what keeps them going.