| Autism spectrum | ||

|---|---|---|

| Other names | Autism spectrum disorder, autistic spectrum disorder, autism spectrum conditions | |

| ||

| Repetitively stacking or lining up objects is associated with the autism spectrum | ||

| Specialty | Clinical psychology, psychiatry, pediatrics, occupational medicine | |

| Symptoms | Problems with communication, social interaction, restricted interests, repetitive behavior | |

| Complications | Social isolation, employment problems, family stress, bullying, self-harm, suicide | |

| Usual onset | By the age of 3 years | |

| Duration | Lifelong or long-term | |

| Causes | Uncertain | |

| Risk factors | Advanced parental age, exposure to valproate during pregnancy, low birth weight | |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms | |

| Differential diagnosis | Intellectual disability, Rett syndrome, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, selective mutism, schizophrenia | |

| Treatment | Behavioral therapy, psychotropic medication | |

| Frequency | 1% of people (62.2 million 2015) | |

The autism spectrum encompasses a range of neurodevelopmental conditions, including autism and Asperger syndrome, generally known as autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Individuals on the autism spectrum typically experience difficulties with social communication and interaction and may also exhibit restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. Symptoms are typically recognized between one and two years of age in boys. However, many children are not diagnosed until they are older. It is also common for diagnosis to be received as an adolescent or as an adult. The term "spectrum" refers to the variation in the type and severity of symptoms. Those in the mild range are typically able to function independently, with some difficulties, while those with moderate to severe symptoms may require more substantial support in their daily lives. Long-term problems may include difficulties in daily living such as managing schedules, hypersensitivities, creating and keeping relationships, and maintaining jobs.

The cause of autism spectrum conditions is uncertain. Risk factors include having an older parent, a family history of autism, and certain genetic conditions. It is estimated that between 64% and 91% of risk is due to family history. Diagnosis is based on symptoms. In 2013, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders version 5 (DSM-5) replaced the previous subgroups of autistic disorder, Asperger syndrome, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), and childhood disintegrative disorder with the single term "autism spectrum disorder".

Support efforts are individualized and typically include learning social, behavioral, and/or other coping skills. Evidence to support the use of medication is not strong. Medication may be used to treat conditions such as depression or anxiety that can be triggered by the stress of feeling and being treated as different, but there is no “cure” for autism as the brain structures involved develop in utero and cannot be changed.

An estimated 1% of the population (62.2 million globally) are on the autism spectrum as of 2015. In the United States it is estimated to affect more than 2% of children (about 1.5 million) as of 2016. Males are diagnosed four times more often than females. The autism rights movement promotes the concept of neurodiversity, which views autism as a natural variation of the brain rather than a disorder to be cured.

Classification

DSM IV (2000)

Autism forms the core of the autism spectrum disorders. Asperger syndrome is closest to autism in signs and likely causes; unlike autism, people with Asperger syndrome have no significant delay in language development or cognitive development, according to the older DSM-IV criteria. PDD-NOS is diagnosed when the criteria are not met for a more specific disorder. Some sources also include Rett syndrome and childhood disintegrative disorder, which share several signs with autism but may have unrelated causes; other sources differentiate them from ASD, but group all of the above conditions into the pervasive developmental disorders.

Autism, Asperger syndrome, and PDD-NOS are sometimes called the autistic disorders instead of ASD, whereas autism itself is often called autistic disorder, childhood autism, or infantile autism. Although the older term pervasive developmental disorder and the newer term autism spectrum disorder largely or entirely overlap, the earlier was intended to describe a specific set of diagnostic labels, whereas the latter refers to a postulated spectrum disorder linking various conditions. ASD is a subset of the broader autism phenotype (BAP), which describes individuals who may not have ASD but do have autistic-like traits, such as avoiding eye contact.

DSM V (2013)

A revision to autism spectrum disorder (ASD) was presented in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders version 5 (DSM-5), released in May 2013. The new diagnosis encompasses previous diagnoses of autistic disorder, Asperger syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, and PDD-NOS. Slightly different diagnostic definitions are used in other countries. Rather than categorizing these diagnoses, the DSM-5 has adopted a dimensional approach to diagnosing disorders that fall underneath the autism spectrum umbrella. Some have proposed that individuals on the autism spectrum may be better represented as a single diagnostic category. Within this category, the DSM-5 has proposed a framework of differentiating each individual by dimensions of severity, as well as associated features (i.e., known genetic disorders, and intellectual disability).

Another change to the DSM includes collapsing social and communication deficits into one domain. Thus, an individual with an ASD diagnosis will be described in terms of severity of social communication symptoms, severity of fixated or restricted behaviors or interests, and hyper- or hyposensitivity to sensory stimuli.

The restricting of onset age has also been loosened from 3 years of age to "early developmental period", with a note that symptoms may manifest later when social demands exceed capabilities.

Signs and symptoms

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by persistent challenges with social communication and social interaction, and by the presence of restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. These symptoms begin in early childhood, and can impact function. There is also a unique disorder called savant syndrome that can co-occur with autism. As many as one in 10 children with autism and savant syndrome can have outstanding skills in music, art, and mathematics. Self-injurious behavior (SIB) is more common and has been found to correlate with intellectual disability. Approximately 50% of people with ASD take part in some type of SIB (head-banging, self-biting).

Other characteristics of ASD include restricted and repetitive behaviors (RRBs). These include a range of gestures and behaviors as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistic Manual for Mental Disorders.

Asperger syndrome was distinguished from autism in the DSM-IV by the lack of delay or deviance in early language development. Additionally, individuals diagnosed with Asperger syndrome did not have significant cognitive delays. PDD-NOS was considered "subthreshold autism" and "atypical autism" because it was often characterized by milder symptoms of autism or symptoms in only one domain (such as social difficulties). The DSM-5 eliminated four separate diagnoses—Asperger syndrome; pervasive developmental disorder, not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS); childhood disintegrative disorder; and autistic disorder—and combined them under the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder.

Developmental course

Most parents report that the onset of autism symptoms occur within the first year of life. There are two possible developmental courses of autism spectrum disorder. One course of development is more gradual in nature, in which parents report concerns in development over the first two years of life and diagnosis is made around 3–4 years of age. Some of the early signs of ASDs in this course include decreased looking at faces, failure to turn when name is called, failure to show interests by showing or pointing, and delayed imaginative play.

A second course of development is characterized by normal or near-normal development in the first 15 months to 3 years before onset of regression or loss of skills. Regression may occur in a variety of domains, including communication, social, cognitive, and self-help skills; however, the most common regression is loss of language. Childhood disintegrative disorder, a DSM-IV diagnosis now included under ASD in DSM-V, is characterized by regression after normal development in the first 3 to 4 years of life.

There continues to be a debate over the differential outcomes based on these two developmental courses. Some studies suggest that regression is associated with poorer outcomes and others report no differences between those with early gradual onset and those who experience a regression period. While there is conflicting evidence surrounding language outcomes in ASD, some studies have shown that cognitive and language abilities at age 2+1⁄2 may help predict language proficiency and production after age 5. Overall, the literature stresses the importance of early intervention in achieving positive longitudinal outcomes.

Social and communication skills

Impairments in social skills present many challenges for individuals with ASD. Deficits in social skills may lead to problems with friendships, romantic relationships, daily living, and vocational success. One study that examined the outcomes of adults with ASD found that, compared to the general population, those with ASD were less likely to be married, but it is unclear whether this outcome was due to deficits in social skills or intellectual impairment, or some other reason.

Prior to 2013, deficits in social function and communication were considered two separate symptoms of autism. The current criteria for autism diagnosis require individuals to have deficits in three social skills: social-emotional reciprocity, nonverbal communication, and developing and sustaining relationships.

Social skills

Some of the symptoms related to social reciprocity include:

- Lack of mutual sharing of interests: many children with autism prefer not to play or interact with others.

- Lack of awareness or understanding of other people's thoughts or feelings: a child may get too close to peers without noticing that this makes them uncomfortable.

- Atypical behaviors for attention: a child may push a peer to gain attention before starting a conversation.

Symptoms related to relationships includes the following:

- Defects in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships.

- Difficulties adjusting behavior to fit social contents:

Communication skills

Communication deficits are due to problems with social-emotional skills like joint attention and social reciprocity.

People with autism spectrum usually display atypical nonverbal behaviors or have difficulties with nonverbal communication:

- Poor eye contact: a child with autism may fail to make eye contact when called by name, or they may avoid making eye contact with an observer. Aversion of gaze can also be seen in anxiety disorders, however poor eye contact in autistic children is not due to shyness or anxiety; rather, it is overall diminished in quantity.

- Facial expressions: impaired use of proper facial expressions are common, they often do not know how to recognize emotions from others' facial expressions, or they may not respond with the appropriate facial expressions. They may have trouble recognizing subtle expressions of emotion and identifying what various emotions mean for the conversation.

- Body language: they may not pick up on body language or social cues such as eye contact and facial expressions if they provide more information than the person can process at that time. They struggle with understanding the context and subtext of conversational or printed situations, and have trouble forming resulting conclusions about the content. This also results in a lack of social awareness and atypical language expression. How emotional processing and facial expressions differ between those on the autism spectrum, and others is not clear, but emotions are processed differently between different partners.

People with autism may experience difficulties with verbal communication:

- Unusual speech: at least half of children with autism speak in a flat, monotone voice or they may not recognize the need to control the volume of their voice in different social settings. For example, they may speak loudly in libraries or movie theaters. Some of the linguistic behaviors in individuals with autism include repetitive or rigid language, and restricted interests in conversation. For example, a child might repeat words or insist on always talking about the same subject.

- Poor pragmatic communication: ASD can present with impairments in pragmatic communication skills, such as difficulty initiating a conversation or failure to consider the interests of the listener to sustain a conversation.

- Language impairment: language impairment is also common in children with autism, but it is not necessary for the diagnosis. Many children with ASD develop language skills at an uneven pace where they easily acquire some aspects of communication, while never fully developing others. In some cases, individuals remain completely nonverbal throughout their lives. The CDC estimated that around 40% of children with autism don’t speak at all, although the accompanying levels of literacy and nonverbal communication skills vary.

- Monotropism: The ability to be focused in on one topic in communication is known as monotropism, and can be compared to "tunnel vision" in the mind for those individuals with ASD. It is also common for individuals with ASD to communicate strong interest in a specific topic, speaking in lesson-like monologues about their passion instead of enabling reciprocal communication with whomever they are speaking to. What looks like self-involvement or indifference toward others stems from a struggle to recognize or remember that other people have their own personalities, perspectives, and interests.

- Language expression: language expression for those on the autism spectrum is often characterized by repetitive and rigid language. Often children with ASD repeat certain words, numbers, or phrases during an interaction, words unrelated to the topic of conversation.

- Echolalia: is also present in individuals with autism in which they respond to a question by repeating the inquiry instead of answering.

Behavioral characteristics

Autism spectrum disorders include a wide variety of characteristics. Some of these include behavioral characteristics which widely range from slow development of social and learning skills to difficulties creating connections with other people. They may develop these difficulties of creating connections due to anxiety or depression, which people with autism are more likely to experience, and as a result isolate themselves.

Other behavioral characteristics include abnormal responses to sensations including sights, sounds, touch, and smell, and problems keeping a consistent speech rhythm. The latter problem influences an individual's social skills, leading to potential problems in how they are understood by communication partners. Behavioral characteristics displayed by those with autism spectrum disorder typically influence development, language, and social competence. Behavioral characteristics of those with autism spectrum disorder can be observed as perceptual disturbances, disturbances of development rate, relating, speech and language, and motility.

The second core symptom of autism spectrum is a pattern of restricted and repetitive behaviors, activities, and interests. In order to be diagnosed with ASD, a child must have at least two of the following behaviors:

- Repetitive behaviors – Repetitive behaviors such as rocking, hand flapping, finger flicking, head banging, or repeating phrases or sounds. These behaviors may occur constantly or only when the child gets stressed, anxious or upset.

- Resistance to change – A strict adherence to routines such as eating certain foods in a specific order, or taking the same path to school every day. The child may have a meltdown if there is any change or disruption to their routine.

- Specialized interests – An excessive in a particular thing or topic, and devote all their attention to it. For example, young children might completely focus on things that spin and ignore everything else. Older children might try to learn everything about a single topic, such as the weather or sports, and talk about it constantly.

- Sensory reactivity– An unusual reaction to certain sensory inputs such as having a negative reaction to specific sounds or textures, being fascinated by lights or movements or having an apparent indifference to pain or heat.

Self-injury

Self-injurious behaviors (SIB) are common in ASD and include head-banging, self-cutting, self-biting, and hair-pulling. These behaviors can result in serious injury or death. Following are theories about the cause of self-injurious behavior in autistic individuals:

- Frequency and/or continuation of self-injurious behavior can be influenced by environmental factors (e.g. reward in return for halting self-injurious behavior). However this theory is not applicable to younger children with autism. There is some evidence that frequency of self-injurious behavior can be reduced by removing or modifying environmental factors that reinforce this behavior.

- Higher rates of self-injury are also noted in socially isolated individuals with autism.

- Self-injury could be a response to modulate pain perception when chronic pain or other health problems that cause pain are present.

- An abnormal basal ganglia connectivity may predispose to self-injurious behavior.

Causes

While specific causes of autism spectrum disorders have yet to be found, many risk factors identified in the research literature may contribute to their development. These risk factors include genetics, prenatal and perinatal factors, neuroanatomical abnormalities, and environmental factors. It is possible to identify general risk factors, but much more difficult to pinpoint specific factors. Given the current state of knowledge, prediction can only be of a global nature and therefore requires the use of general markers.

Genetics

As of 2018, it appeared that somewhere between 74% and 93% of ASD risk is heritable. After an older child is diagnosed with ASD, 7–20% of subsequent children are likely to be as well. If parents have a child with ASD they have a 2% to 8% chance of having a second child with ASD. If the child with ASD is an identical twin the other will be affected 36 to 95 percent of the time. If they are fraternal twins the other will only be affected up to 31 percent of the time.

As of 2018, understanding of genetic risk factors had shifted from a focus on a few alleles to an understanding that genetic involvement in ASD is probably diffuse, depending on a large number of variants, some of which are common and have a small effect, and some of which are rare and have a large effect. The most common gene disrupted with large effect rare variants appeared to be CHD8, but less than 0.5% of people with ASD have such a mutation. Some ASD is associated with clearly genetic conditions, like fragile X syndrome; however only around 2% of people with ASD have fragile X. Hypotheses from evolutionary psychiatry suggest that these genes persist because they are linked to human inventiveness, intelligence or systemising.

Current research suggests that genes that increase susceptibility to ASD are ones that control protein synthesis in neuronal cells in response to cell needs, activity and adhesion of neuronal cells, synapse formation and remodeling, and excitatory to inhibitory neurotransmitter balance. Therefore despite up to 1000 different genes thought to contribute to increased risk of ASD, all of them eventually affect normal neural development and connectivity between different functional areas of the brain in a similar manner that is characteristic of an ASD brain. Some of these genes are known to modulate production of the GABA neurotransmitter which is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the nervous system. These GABA-related genes are underexpressed in an ASD brain. On the other hand, genes controlling expression of glial and immune cells in the brain e.g. astrocytes and microglia, respectively, are overexpressed which correlates with increased number of glial and immune cells found in postmortem ASD brains. Some genes under investigation in ASD pathophysiology are those that affect the mTOR signaling pathway which supports cell growth and survival.

All these genetic variants contribute to the development of the autistic spectrum, however, it can not be guaranteed that they are determinants for the development.

Early life

Several prenatal and perinatal complications have been reported as possible risk factors for autism. These risk factors include maternal gestational diabetes, maternal and paternal age over 30, bleeding after first trimester, use of prescription medication (e.g. valproate) during pregnancy, and meconium in the amniotic fluid. While research is not conclusive on the relation of these factors to autism, each of these factors has been identified more frequently in children with autism, compared to their siblings who do not have autism, and other typically developing youth. While it is unclear if any single factors during the prenatal phase affect the risk of autism, complications during pregnancy may be a risk.

Low vitamin D levels in early development has been hypothesized as a risk factor for autism.

Disproven vaccine hypothesis

In 1998 Andrew Wakefield led a fraudulent study that suggested that the MMR vaccine may cause autism. This conjecture suggested that autism results from brain damage caused either by the MMR vaccine itself, or by thimerosal, a vaccine preservative. No convincing scientific evidence supports these claims, and further evidence continues to refute them, including the observation that the rate of autism continues to climb despite elimination of thimerosal from routine childhood vaccines. A 2014 meta-analysis examined ten major studies on autism and vaccines involving 1.25 million children worldwide; it concluded that neither the MMR vaccine, which has never contained thimerosal, nor the vaccine components thimerosal or mercury, lead to the development of ASDs.

Pathophysiology

In general, neuroanatomical studies support the concept that autism may involve a combination of brain enlargement in some areas and reduction in others. These studies suggest that autism may be caused by abnormal neuronal growth and pruning during the early stages of prenatal and postnatal brain development, leaving some areas of the brain with too many neurons and other areas with too few neurons. Some research has reported an overall brain enlargement in autism, while others suggest abnormalities in several areas of the brain, including the frontal lobe, the mirror neuron system, the limbic system, the temporal lobe, and the corpus callosum.

In functional neuroimaging studies, when performing theory of mind and facial emotion response tasks, the median person on the autism spectrum exhibits less activation in the primary and secondary somatosensory cortices of the brain than the median member of a properly sampled control population. This finding coincides with reports demonstrating abnormal patterns of cortical thickness and grey matter volume in those regions of autistic persons' brains.

Brain connectivity

Brains of autistic individuals have been observed to have abnormal connectivity and the degree of these abnormalities directly correlates with the severity of autism. Following are some observed abnormal connectivity patterns in autistic individuals:

- Decreased connectivity between different specialized regions of the brain (e.g. lower neuron density in corpus callosum) and relative overconnectivity within specialized regions of the brain by adulthood. Connectivity between different regions of the brain ('long-range' connectivity) is important for integration and global processing of information and comparing incoming sensory information with the existing model of the world within the brain. Connections within each specialized regions ('short-range' connections) are important for processing individual details and modifying the existing model of the world within the brain to more closely reflect incoming sensory information. In infancy, children at high risk for autism that were later diagnosed with autism were observed to have abnormally high long-range connectivity which then decreased through childhood to eventual long-range underconnectivity by adulthood.

- Abnormal preferential processing of information by the left hemisphere of the brain vs. preferential processing of information by right hemisphere in neurotypical individuals. The left hemisphere is associated with processing information related to details whereas the right hemisphere is associated with processing information in a more global and integrated sense that is essential for pattern recognition. For example, visual information like face recognition is normally processed by the right hemisphere which tends to integrate all information from an incoming sensory signal, whereas an ASD brain preferentially processes visual information in the left hemisphere where information tends to be processed for local details of the face rather than the overall configuration of the face. This left lateralization negatively impacts both facial recognition and spatial skills.

- Increased functional connectivity within the left hemisphere which directly correlates with severity of autism. This observation also supports preferential processing of details of individual components of sensory information over global processing of sensory information in an ASD brain.

- Prominent abnormal connectivity in the frontal and occipital regions. In autistic individuals low connectivity in the frontal cortex was observed from infancy through adulthood. This is in contrast to long-range connectivity which is high in infancy and low in adulthood in ASD. Abnormal neural organization is also observed in the Broca's area which is important for speech production.

Neuropathology

Listed below are some characteristic findings in ASD brains on molecular and cellular levels regardless of the specific genetic variation or mutation contributing to autism in a particular individual:

- Limbic system with smaller neurons that are more densely packed together. Given that the limbic system is the main center of emotions and memory in the human brain, this observation may explain social impairment in ASD.

- Fewer and smaller Purkinje neurons in the cerebellum. New research suggest a role of the cerebellum in emotional processing and language.

- Increased number of astrocytes and microglia in the cerebral cortex. These cells provide metabolic and functional support to neurons and act as immune cells in the nervous system, respectively.

- Increased brain size in early childhood causing macrocephaly in 15–20% of ASD individuals. The brain size however normalizes by mid-childhood. This variation in brain size in not uniform in the ASD brain with some parts like the frontal and temporal lobes being larger, some like the parietal and occipital lobes being normal sized, and some like cerebellar vermis, corpus callosum, and basal ganglia being smaller than neurotypical individuals.

- Cell-adhesion molecules (CAMs) that are essential to formation and maintenance of connections between neurons, neuroligins found on postsynaptic neurons that bind presynaptic CAMs, and proteins that anchor CAMs to neurons are all found to be mutated in ASD.

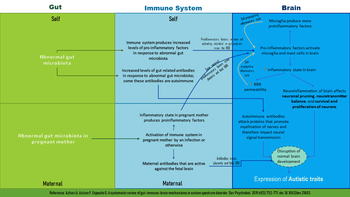

Gut-immune-brain axis

Up to 70% of autistic individuals have GI related problems like reflux, diarrhea, constipation, inflammatory bowel disease, and food allergies. The severity of GI symptoms is directly proportional to the severity of autism. It has also been shown that the makeup of gut bacteria in ASD patients is different than that of neurotypical individuals. This has raised the question of influence of gut bacteria on ASD development via inducing an inflammatory state.

Listed below are some research findings on the influence of gut bacteria and abnormal immune responses on brain development:

- Some studies on rodents have shown gut bacteria influencing emotional functions and neurotransmitter balance in the brain, both of which are impacted in ASD.

- The immune system is thought to be the intermediary that modulates the influence of gut bacteria on the brain. Some ASD individuals have a dysfunctional immune system with higher numbers of some types of immune cells, biochemical messengers and modulators, and autoimmune antibodies. Increased inflammatory biomarkers correlate with increased severity of ASD symptoms and there is evidence to support a state of chronic brain inflammation in ASD.

- More pronounced inflammatory responses to bacteria were found in ASD individuals with an abnormal gut microbiota. Additionally IgA antibodies that are central to gut immunity were also found in elevated levels in ASD populations. Some of these antibodies may also attack proteins that support myelination of the brain, a process that is important for robust transmission of neural signal in many nerves.

- Activation of the maternal immune system during pregnancy (by gut bacteria, bacterial toxins, an infection, or non-infectious causes) and gut bacteria in the mother that induce increased levels of Th17, a proinflammatory immune cell, have been associated with an increased risk of autism. Some maternal IgG antibodies that cross the placenta to provide passive immunity to the fetus can also attack the fetal brain. One study found that 12% of mothers of autistic children have IgG that are active against the fetal brain.

- Inflammation within the gut itself does not directly affect brain development. Rather it is the inflammation within the brain promoted by inflammatory responses to harmful gut microbiome that impact brain development.

- Proinflammatory biomessengers IFN-γ, IFN-α, TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-17 have been shown to promote autistic behaviors in animal models. Giving anti-IL-6 and anti-IL-17 along with IL-6 and IL-17, respectively, have been shown to negate this effect in the same animal models.

- Some gut proteins and microbial products can cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and activate mast cells in the brain. Mast cells release proinflammatory factors and histamine which further increase BBB permeability and help set up a cycle of chronic inflammation.

Mirror neuron system

The mirror neuron system (MNS) consists of a network of brain areas that have been associated with empathy processes in humans. In humans, the MNS has been identified in the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and the inferior parietal lobule (IPL) and is thought to be activated during imitation or observation of behaviors. The connection between mirror neuron dysfunction and autism is tentative, and it remains to be seen how mirror neurons may be related to many of the important characteristics of autism.

"Social brain" interconnectivity

A number of discrete brain regions and networks among regions that are involved in dealing with other people have been discussed together under the rubric of the "social brain". As of 2012, there is a consensus that autism spectrum is likely related to problems with interconnectivity among these regions and networks, rather than problems with any specific region or network.

Temporal lobe

Functions of the temporal lobe are related to many of the deficits observed in individuals with ASDs, such as receptive language, social cognition, joint attention, action observation, and empathy. The temporal lobe also contains the superior temporal sulcus (STS) and the fusiform face area (FFA), which may mediate facial processing. It has been argued that dysfunction in the STS underlies the social deficits that characterize autism. Compared to typically developing individuals, one fMRI study found that individuals with so-called 'high-functioning autism' had reduced activity in the FFA when viewing pictures of faces.

Mitochondria

ASD could be linked to mitochondrial disease (MD), a basic cellular abnormality with the potential to cause disturbances in a wide range of body systems. A 2012 meta-analysis study, as well as other population studies have shown that approximately 5% of children with ASD meet the criteria for classical MD. It is unclear why the MD occurs considering that only 23% of children with both ASD and MD present with mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) abnormalities.

Serotonin

Serotonin is a major neurotransmitter in the nervous system and contributes to formation of new neurons (neurogenesis), formation of new connections between neurons (synaptogenesis), remodeling of synapses, and survival and migration of neurons, processes that are necessary for a developing brain and some also necessary for learning in the adult brain. 45% of ASD individuals have been found to have increased blood serotonin levels. It has been hypothesized that increased activity of serotonin in the developing brain may facilitate the onset of autism spectrum disorder, with an association found in six out of eight studies between the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) by the pregnant mother and the development of ASD in the child exposed to SSRI in the antenatal environment. The study could not definitively conclude SSRIs caused the increased risk for ASDs due to the biases found in those studies, and the authors called for more definitive, better conducted studies. Confounding by indication has since then been shown to be likely. However, it is also hypothesized that SSRIs may help reduce symptoms of ASD and even positively affect brain development in some ASD patients.

Diagnosis

ASD can be detected as early as 18 months or even younger in some cases. A reliable diagnosis can usually be made by the age of two years, however, because of delays in seeking and administering assessments, diagnoses often occur much later. A study in 2005 found that children diagnosed with autistic disorder and PDD-NOS are typically diagnosed at age 3 while children with aspergers are typically diagnosed at age 7.

The diverse expressions of ASD behavioral and observational symptoms and absence of one specific genetic or molecular marker for the disorder pose diagnostic challenges to clinicians who use assessment methods based on symptoms alone. Individuals with an ASD may present at various times of development (e.g., toddler, child, or adolescent), and symptom expression may vary over the course of development. Furthermore, clinicians who use those methods must differentiate among pervasive developmental disorders, and may also consider similar conditions, including intellectual disability not associated with a pervasive developmental disorder, specific language disorders, ADHD, anxiety, and psychotic disorders. Ideally the diagnosis of ASD should be given by a team of professionals from different disciplines (e.g. child psychiatrists, child neurologists, psychologists) and only after the child has been observed in many different settings.

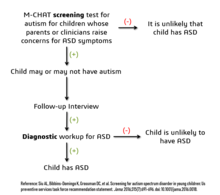

Considering the unique challenges in diagnosing ASD using behavioral and observational assessment, specific practice parameters for its assessment were published by the American Academy of Neurology in the year 2000, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in 1999, and a consensus panel with representation from various professional societies in 1999. The practice parameters outlined by these societies include an initial screening of children by general practitioners (i.e., "Level 1 screening") and for children who fail the initial screening, a comprehensive diagnostic assessment by experienced clinicians (i.e. "Level 2 evaluation"). Furthermore, it has been suggested that assessments of children with suspected ASD be evaluated within a developmental framework, include multiple informants (e.g., parents and teachers) from diverse contexts (e.g., home and school), and employ a multidisciplinary team of professionals (e.g., clinical psychologists, neuropsychologists, and psychiatrists).

As of 2019, psychologists would wait until a child showed initial evidence of ASD tendencies, then administer various psychological assessment tools to assess for ASD. Among these measurements, the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) are considered the "gold standards" for assessing autistic children. The ADI-R is a semi-structured parent interview that probes for symptoms of autism by evaluating a child's current behavior and developmental history. The ADOS is a semistructured interactive evaluation of ASD symptoms that is used to measure social and communication abilities by eliciting several opportunities (or "presses") for spontaneous behaviors (e.g., eye contact) in standardized context. Various other questionnaires (e.g., The Childhood Autism Rating Scale, Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist) and tests of cognitive functioning (e.g., The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test) are typically included in an ASD assessment battery.

Screening

Screening recommendations for autism in children younger than 3 years are:

- US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) does not recommend universal screen of young children for autism due to poor evidence of benefits of this screening when parents and clinicians have no concerns about ASD. The major concern is a false-positive diagnosis that would burden a family with very time consuming and financially demanding treatment interventions when it is not truly required. USPSTF also did not find any robust studies showing effectiveness of behavioral therapies in reducing ASD symptom severity

- American Academy of Pediatrics recommends ASD screening of all children between the ages if 18 and 24 months. The AAP also recommends that children who screen positive for ASD be referred to ASD treatment services without waiting for a comprehensive diagnostic workup.

- The American Academy of Family Physicians did not find sufficient evidence of benefit of universal early screening for ASD

- The American Academy of Neurology and Child Neurology Society recommends general routine screening for delayed or abnormal development in children followed by screening for ASD only if indicated by the general developmental screening

- The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recommend routinely screening autism symptoms in young children

- The UK National Screening Committee does not recommend universal ASD screening in young children. Their main concerns includes higher chances of misdiagnosis at younger ages and lack of evidence of effectiveness of early interventions

Misdiagnosis

There is a significant level of misdiagnosis of autism in neurodevelopmentally normal children; 18–37% of children diagnosed with ASD eventually lose their diagnosis. This high rate of lost diagnosis cannot be accounted for by successful ASD treatment alone. The most common reason parents reported as the cause of lost ASD diagnosis was new information about the child (73.5%), such as a replacement diagnosis. Other reasons included a diagnosis given so the child could receive ASD treatment (24.2%), ASD treatment success or maturation (21%), and parents disagreeing with the initial diagnosis (1.9%).

Many of the children who were later found not to meet ASD diagnosis criteria then received diagnosis for another developmental disorder like ADHD (most common), sensory disorders, anxiety, personality disorder, or learning disability. Neurodevelopment and psychiatric disorders that are commonly misdiagnosed as ASD include specific language impairment, social communication disorder, anxiety disorder, reactive attachment disorder, cognitive impairment, visual impairment, hearing impairment and normal behavioral variations. Some normal behavioral variations that resemble autistic traits are repetitive behaviors, sensitivity to change in daily routines, focused interests, and toe-walking. These are considered normal behavioral variations when they do not cause impaired function. Boys are more likely to exhibit repetitive behaviors especially when excited, tired, bored, or stressed. Some ways of distinguishing normal behavioral variations from abnormal behaviors are the ability of the child to suppress these behaviors and the absence of these behaviors during sleep.

Prognosis

Few children who are correctly diagnosed with ASD are thought to lose this diagnosis due to treatment or outgrowing their symptoms. Children with poor treatment outcomes also tend to be ones that had moderate to severe forms of ASD, whereas children who appear to have responded to treatment are the ones with milder forms of ASD.

Comorbidity

Autism spectrum disorders tend to be highly comorbid with other disorders. Comorbidity may increase with age and may worsen the course of youth with ASDs and make intervention/treatment more difficult. Distinguishing between ASDs and other diagnoses can be challenging, because the traits of ASDs often overlap with symptoms of other disorders, and the characteristics of ASDs make traditional diagnostic procedures difficult.

- The most common medical condition occurring in individuals with autism spectrum disorders is seizure disorder or epilepsy, which occurs in 11–39% of individuals with ASD.

- Tuberous sclerosis, an autosomal dominant genetic condition in which non-malignant tumors grow in the brain and on other vital organs, is present in 1–4% of individuals with ASDs.

- Intellectual disabilities are some of the most common comorbid disorders with ASDs. Recent estimates suggest that 40–69% of individuals with ASD have some degree of an intellectual disability, more likely to be severe for females. A number of genetic syndromes causing intellectual disability may also be comorbid with ASD, including fragile X, Down, Prader-Willi, Angelman, Williams syndrome and SYNGAP1-related intellectual disability.

- Learning disabilities are also highly comorbid in individuals with an ASD. Approximately 25–75% of individuals with an ASD also have some degree of a learning disability.

- Various anxiety disorders tend to co-occur with autism spectrum disorders, with overall comorbidity rates of 7–84%. Rates of comorbid depression in individuals with an ASD range from 4–58%. The relationship between ASD and schizophrenia remains a controversial subject under continued investigation, and recent meta-analyses have examined genetic, environmental, infectious, and immune risk factors that may be shared between the two conditions.

- Deficits in ASD are often linked to behavior problems, such as difficulties following directions, being cooperative, and doing things on other people's terms. Symptoms similar to those of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can be part of an ASD diagnosis.

- Sensory processing disorder is also comorbid with ASD, with comorbidity rates of 42–88%.

- Starting in adolescence, some people with Asperger syndrome (26% in one sample) fall under the criteria for the similar condition schizoid personality disorder, which is characterised by a lack of interest in social relationships, a tendency towards a solitary or sheltered lifestyle, secretiveness, emotional coldness, detachment and apathy. Asperger syndrome was traditionally called "schizoid disorder of childhood".

Management

There is no known cure for autism, although those with Asperger syndrome and those who have autism and require little-to-no support are more likely to experience a lessening of symptoms over time. Several interventions can help children with autism. The main goals of treatment are to lessen associated deficits and family distress, and to increase quality of life and functional independence. In general, higher IQs are correlated with greater responsiveness to treatment and improved treatment outcomes. Although evidence-based interventions for autistic children vary in their methods, many adopt a psychoeducational approach to enhancing cognitive, communication, and social skills while minimizing problem behaviors. It has been argued that no single treatment is best and treatment is typically tailored to the child's needs.

Non-pharmacological interventions

Intensive, sustained special education or remedial education programs and behavior therapy early in life can help children acquire self-care, social, and job skills. Available approaches include applied behavior analysis, developmental models, structured teaching, speech and language therapy, social skills therapy, and occupational therapy. Among these approaches, interventions either treat autistic features comprehensively, or focus treatment on a specific area of deficit. Generally, when educating those with autism, specific tactics may be used to effectively relay information to these individuals. Using as much social interaction as possible is key in targeting the inhibition autistic individuals experience concerning person-to-person contact. Additionally, research has shown that employing semantic groupings, which involves assigning words to typical conceptual categories, can be beneficial in fostering learning.

There has been increasing attention to the development of evidence-based interventions for young children with ASD. Two theoretical frameworks outlined for early childhood intervention include applied behavioral analysis (ABA) and the developmental social-pragmatic model (DSP). Although ABA therapy has a strong evidence base, particularly in regard to early intensive home-based therapy, ABA's effectiveness may be limited by diagnostic severity and IQ of the person affected by ASD. The Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology has deemed two early childhood interventions as "well-established": individual comprehensive ABA, and focused teacher-implemented ABA combined with DSP.

Another evidence-based intervention that has demonstrated efficacy is a parent training model, which teaches parents how to implement various ABA and DSP techniques themselves. Various DSP programs have been developed to explicitly deliver intervention systems through at-home parent implementation.

A multitude of unresearched alternative therapies have also been implemented. Many have resulted in harm to autistic people and should not be employed unless proven to be safe. However, a recent systematic review on adults with autism has provided emerging evidence for decreasing stress, anxiety, ruminating thoughts, anger, and aggression through mindfulness-based interventions for improving mental health.

In October 2015, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) proposed new evidence-based recommendations for early interventions in ASD for children under 3. These recommendations emphasize early involvement with both developmental and behavioral methods, support by and for parents and caregivers, and a focus on both the core and associated symptoms of ASD. However, a Cochrane review found no evidence that early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI) is effective in reducing behavioral problems associated with autism in most children with ASD but did help improve IQ and language skills. The Cochrane review did acknowledge that this may be due to the low quality of studies currently available on EIBI and therefore providers should recommend EIBI based on their clinical judgement and the family's preferences. No adverse effects of EIBI treatment were found. Studies on pet therapy have shown positive effects.

Generally speaking, treatment of ASD focuses on behavioral and educational interventions to target its two core symptoms: social communication deficits and restricted, repetitive behaviors. If symptoms continue after behavioral strategies have been implemented, some medications can be recommended to target specific symptoms or co-existing problems such as restricted and repetitive behaviors (RRBs), anxiety, depression, hyperactivity/inattention and sleep disturbance. Melatonin for example can be used for sleep problems.

While there are a number of parent-mediated behavioral therapies to target social communication deficits in children with autism, there is uncertainty regarding the efficacy of interventions to treat RRBs.

Pharmacological interventions

There is some emerging data that show positive effects of risperidone on restricted and repetitive behaviors (i.e., stimming; e.g., flapping, twisting, complex whole-body movements), but due to the small sample size of these studies and the concerns about its side effects, antipsychotics are not recommended as primary treatment of RRBs.

Epidemiology

While rates of autism spectrum disorders are consistent across cultures, they vary greatly by gender, with boys diagnosed far more frequently than girls. The average male-to-female diagnosis ratio for ASDs is 4.2:1, with 1 in 70 boys, but only 1 in 315 girls. Girls, however, are more likely to have associated cognitive impairment. Among those with an ASD and intellectual disability, the sex ratio may be closer to 2:1. Prevalence differences may be a result of gender differences in expression of clinical symptoms, with women and girls with autism showing less atypical behaviors and, therefore, less likely to receive an ASD diagnosis.

Autism prevalence has been estimated at 1–2 per 1,000, Asperger syndrome at roughly 0.6 per 1,000, childhood disintegrative disorder at 0.02 per 1,000, and PDD-NOS at 3.7 per 1,000. These rates are consistent across cultures and ethnic groups, as autism is considered a universal disorder.

Using DSM-V criteria 92% of the children diagnosed with a autism spectrum disorder per DSM-IV still meet the diagnostic criteria of an autism spectrum disorder. However if both Autism Spectrum Disorder and Social Communication Disorder categories of DSM-V are combined, the prevalence of autism is mostly unchanged from the prevalence per the DSM-IV criteria. The best estimate for prevalence of ASD is 0.7% or 1 child in 143 children. Relatively mild forms of autism, such as Aspergers as well as other developmental disorders were included in the recent DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. ASD rates were constant between 2014 and 2016 but twice the rate compared to the time period between 2011 and 2014 (1.25 vs 2.47%). A Canadian meta-analysis from 2019 confirmed these effects as the profiles of people diagnosed with autism became less and less different from the profiles of the general population. In the US, the rates for diagnosed ASD have been steadily increasing since 2000 when records began being kept. While it remains unclear whether this trend represents a true rise in incidence, it likely reflects changes in ASD diagnostic criteria, improved detection, and increased public awareness of autism.

United States

In the United States it is estimated to affect more than 2% of children (about 1.5 million) as of 2016. According to the latest CDC prevalence reports, 1 in 59 children (1.7%) in the United States had a diagnosis of ASD in 2014, reflecting a 2.5-fold increase from the prevalence rate in 2000. Prevalence is estimated at 6 per 1,000 for autism spectrum disorders as a whole, although prevalence rates vary for each of the developmental disorders in the spectrum.

History

The word autism comes from the greek word "autos" whose meaning was first established by Eugen Bleuler. Autism as it is known today can be drawn back to the late 1930's. Two separate psychiatrists used the word autism to describe the patients they were studying in their own clinical research. Victor, the Wild Boy of Aveyron, was found deep in the woods of Central France. He was non-verbal amongst his teenage years, and his case was widely popular among society for its time. Such cases brought awareness to autism, and more research was conducted on the natural dimensions of human behavior. The discussion of autism prior to the twentieth century is one that brings about much controversy. Without researchers being able to meet a consensus on the varying forms around the condition, there was a lack of research being conducted on the disorder. Discussing the syndrome and its complexity frustrated researchers. Controversies have surrounded various claims regarding the etiology of autism spectrum disorders. In the 1950s, the "refrigerator mother theory" emerged as an explanation for autism. The hypothesis was based on the idea that autistic behaviors stem from the emotional frigidity, lack of warmth, and cold, distant, rejecting demeanor of a child's mother. Naturally, parents of children with an autism spectrum disorder suffered from blame, guilt, and self-doubt, especially as the theory was embraced by the medical establishment and went largely unchallenged into the mid-1960s. The "refrigerator mother" theory has since continued to be refuted in scientific literature, including a 2015 systematic review which showed no association between caregiver interaction and language outcomes in ASD.

Leo Kanner, a child psychiatrist, was the first person to describe ASD as a neurodevelopmental disorder in 1943 by calling it 'infantile autism' and therefore rejected the 'refrigerator mother' theory.

Another controversial claim suggests that watching extensive amounts of television may cause autism. This hypothesis was largely based on research suggesting that the increasing rates of autism in the 1970s and 1980s were linked to the growth of cable television at this time.

Society and culture

Caregivers

Families who care for an autistic child face added stress from a number of different causes. Parents may struggle to understand the diagnosis and to find appropriate care options. Parents often take a negative view of the diagnosis, and may struggle emotionally. More than half of parents over the age of 50 are still living with their child as about 85% of people with ASD have difficulties living independently.

Autism rights movement

The autism rights movement is a social movement within the context of disability rights that emphasizes the concept of neurodiversity, viewing the autism spectrum as a result of natural variations in the human brain rather than a disorder to be cured. The autism rights movement advocates for including greater acceptance of autistic behaviors; therapies that focus on coping skills rather than imitating the behaviors of those without autism; and the recognition of the autistic community as a minority group. Autism rights or neurodiversity advocates believe that the autism spectrum is genetic and should be accepted as a natural expression of the human genome. This perspective is distinct from two other likewise distinct views: the medical perspective, that autism is caused by a genetic defect and should be addressed by targeting the autism gene(s), and fringe theories that autism is caused by environmental factors such as vaccines. A common criticism against autistic activists is that the majority of them are "high-functioning" or have Asperger syndrome and do not represent the views of "low-functioning" autistic people.

Academic performance

The number of students identified and served as eligible for autism services in the United States has increased from 5,413 children in 1991–1992 to 370,011 children in the 2010–2011 academic school year. The United States Department of Health and Human Services reported approximately 1 in 68 children at age 8 are diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) although onset is typically between ages 2 and 4.

The increasing number of students with ASD in the schools presents significant challenges to teachers, school psychologists, and other school professionals. These challenges include developing a consistent practice that best support the social and cognitive development of the increasing number of students with ASD. Although there is considerable research addressing assessment, identification, and support services for children with ASD, there is a need for further research focused on these topics within the school context. Further research on appropriate support services for students with ASD will provide school psychologists and other education professionals with specific directions for advocacy and service delivery that aim to enhance school outcomes for students with ASD.

Attempts to identify and use best intervention practices for students with autism also pose a challenge due to overdependence on popular or well-known interventions and curricula. Some evidence suggests that although these interventions work for some students, there remains a lack of specificity for which type of student, under what environmental conditions (one-on-one, specialized instruction or general education) and for which targeted deficits they work best. More research is needed to identify what assessment methods are most effective for identifying the level of educational needs for students with ASD.

A difficulty for academic performance in students with ASD is the tendency to generalize learning. Learning is different for each student, which is the same for students with ASD. To assist in learning, accommodations are commonly put into place for students with differing abilities. The existing schema of these students works in different ways and can be adjusted to best support the educational development for each student.

The cost of educating a student with ASD in the US is about $8,600 a year more than the cost of educating an average student, which is about $12,000.

Employment

About half of people in their 20s with autism are unemployed, and one third of those with graduate degrees may be unemployed. While employers state hiring concerns about productivity and supervision, experienced employers of autistics give positive reports of above average memory and detail orientation as well as a high regard for rules and procedure in autistic employees. A majority of the economic burden of autism is caused by lost productivity in the job market. Some studies also find decreased earning among parents who care for autistic children. Adding content related to autism in existing diversity training can clarify misconceptions, support employees, and help provide new opportunities for autistics.