From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A virus is a tiny infectious agent that reproduces inside the cells of living hosts. When infected, the host cell is forced to rapidly produce thousands of identical copies of the original virus. Unlike most living things,

viruses do not have cells that divide; new viruses assemble in the

infected host cell. But unlike simpler infectious agents like prions, they contain genes, which allow them to mutate and evolve. Over 4,800 species of viruses have been described in detail out of the millions in the environment. Their origin is unclear: some may have evolved from plasmids—pieces of DNA that can move between cells—while others may have evolved from bacteria.

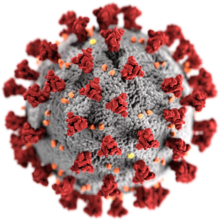

Viruses are made of either two or three parts. All include genes. These genes contain the encoded biological information of the virus and are built from either DNA or RNA. All viruses are also covered with a protein coat to protect the genes. Some viruses may also have an envelope of fat-like substance

that covers the protein coat, and makes them vulnerable to soap. A

virus with this "viral envelope" uses it—along with specific receptors—to enter a new host cell. Viruses vary in shape from the simple helical and icosahedral to more complex structures. Viruses range in size from 20 to 300 nanometres; it would take 33,000 to 500,000 of them, side by side, to stretch to 1 centimetre (0.4 in).

Viruses spread in many ways. Although many are very specific about which host species or tissue they attack, each species of virus relies on a particular method to copy itself. Plant viruses are often spread from plant to plant by insects and other organisms, known as vectors. Some viruses of humans and other animals are spread by exposure to infected bodily fluids. Viruses such as influenza are spread through the air by droplets of moisture when people cough or sneeze. Viruses such as norovirus are transmitted by the faecal–oral route, which involves the contamination of hands, food and water. Rotavirus is often spread by direct contact with infected children. The human immunodeficiency virus, HIV, is transmitted by bodily fluids transferred during sex. Others, such as the dengue virus, are spread by blood-sucking insects.

Viruses, especially those made of RNA, can mutate rapidly to give rise to new types. Hosts may have little protection against such new forms. Influenza virus, for example, changes often, so a new vaccine is needed each year. Major changes can cause pandemics, as in the 2009 swine influenza

that spread to most countries. Often, these mutations take place when

the virus has first infected other animal hosts. Some examples of such "zoonotic" diseases include coronavirus in bats, and influenza in pigs and birds, before those viruses were transferred to humans.

Viral infections can cause disease in humans, animals and plants.

In healthy humans and animals, infections are usually eliminated by the

immune system, which can provide lifetime immunity to the host for that virus. Antibiotics, which work against bacteria, have no impact, but antiviral drugs can treat life-threatening infections. Those vaccines that produce lifelong immunity can prevent some infections.

Discovery

In 1884, French microbiologist Charles Chamberland invented the Chamberland filter (or Chamberland–Pasteur filter), that contains pores smaller than bacteria. He could then pass a solution containing bacteria through the filter, and completely remove them. In the early 1890s, Russian biologist Dmitri Ivanovsky used this method to study what became known as the tobacco mosaic virus. His experiments showed that extracts from the crushed leaves of infected tobacco plants remain infectious after filtration.

At the same time, several other scientists showed that, although

these agents (later called viruses) were different from bacteria and

about one hundred times smaller, they could still cause disease. In

1899, Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck observed that the agent only multiplied when in dividing cells. He called it a "contagious living fluid" (Latin: contagium vivum fluidum)—or a "soluble living germ" because he could not find any germ-like particles. In the early 20th century, English bacteriologist Frederick Twort discovered viruses that infect bacteria, and French-Canadian microbiologist Félix d'Herelle described viruses that, when added to bacteria growing on agar,

would lead to the formation of whole areas of dead bacteria. Counting

these dead areas allowed him to calculate the number of viruses in the

suspension.

The invention of the electron microscope in 1931 brought the first images of viruses. In 1935, American biochemist and virologist Wendell Meredith Stanley examined the tobacco mosaic virus and found it to be mainly made from protein. A short time later, this virus was shown to be made from protein and RNA.

A problem for early scientists was that they did not know how to grow

viruses without using live animals. The breakthrough came in 1931, when

American pathologists Ernest William Goodpasture and Alice Miles Woodruff grew influenza, and several other viruses, in fertilised chickens' eggs. Some viruses could not be grown in chickens' eggs. This problem was solved in 1949, when John Franklin Enders, Thomas Huckle Weller, and Frederick Chapman Robbins grew polio virus in cultures of living animal cells. Over 4,800 species of viruses have been described in detail.

Origins

Viruses co-exist with life wherever it occurs. They have probably

existed since living cells first evolved. Their origin remains unclear

because they do not fossilize, so molecular techniques have been the best way to hypothesise

about how they arose. These techniques rely on the availability of

ancient viral DNA or RNA, but most viruses that have been preserved and

stored in laboratories are less than 90 years old. Molecular methods have only been successful in tracing the ancestry of viruses that evolved in the 20th century. New groups of viruses might have repeatedly emerged at all stages of the evolution of life. There are three major theories about the origins of viruses:

- Regressive theory

- Viruses may have once been small cells that parasitised larger cells. Eventually, the genes they no longer needed for a parasitic way of life were lost. The bacteria Rickettsia and Chlamydia

are living cells that, like viruses, can reproduce only inside host

cells. This lends credence to this theory, as their dependence on being

parasites may have led to the loss of the genes that once allowed them

to live on their own.

- Cellular origin theory

- Some viruses may have evolved from bits of DNA or RNA that "escaped"

from the genes of a larger organism. The escaped DNA could have come

from plasmids—pieces of DNA that can move between cells—while others may have evolved from bacteria.

- Coevolution theory

- Viruses may have evolved from complex molecules of protein and DNA

at the same time as cells first appeared on earth, and would have

depended on cellular life for many millions of years.

There are problems with all of these theories. The regressive

hypothesis does not explain why even the smallest of cellular parasites

do not resemble viruses in any way. The escape or the cellular origin

hypothesis does not explain the presence of unique structures in viruses

that do not appear in cells. The coevolution, or "virus-first"

hypothesis, conflicts with the definition of viruses, because viruses

depend on host cells. Also, viruses are recognised as ancient, and to have origins that pre-date the divergence of life into the three domains. This discovery has led modern virologists to reconsider and re-evaluate these three classical hypotheses.

Structure

Simplified diagram of the structure of a virus

A virus particle, also called a virion, consists of genes made from DNA or RNA which are surrounded by a protective coat of protein called a capsid. The capsid is made of many smaller, identical protein molecules called capsomers. The arrangement of the capsomers can either be icosahedral (20-sided), helical, or more complex. There is an inner shell around the DNA or RNA called the nucleocapsid, made out of proteins. Some viruses are surrounded by a bubble of lipid (fat) called an envelope, which makes them vulnerable to soap and alcohol.

Size

Viruses are among the smallest infectious agents, and are too small to be seen by light microscopy; most of them can only be seen by electron microscopy. Their sizes range from 20 to 300 nanometres; it would take 30,000 to 500,000 of them, side by side, to stretch to one centimetre (0.4 in).

In comparison, bacteria are typically around 1000 nanometres

(1 micrometer) in diameter, and host cells of higher organisms are

typically a few tens of micrometers. Some viruses such as megaviruses and pandoraviruses are relatively large viruses. At around 1000 nanometres, these viruses, which infect amoebae, were discovered in 2003 and 2013. They are around ten times wider (and thus a thousand times larger in volume) than influenza viruses, and the discovery of these "giant" viruses astonished scientists.

Genes

The genes of viruses are made from DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) and,

in many viruses, RNA (ribonucleic acid). The biological information

contained in an organism is encoded in its DNA or RNA. Most organisms use DNA, but many viruses have RNA as their genetic material. The DNA or RNA of viruses consists of either a single strand or a double helix.

Viruses can reproduce rapidly because they have relatively few genes. For example, influenza virus has only eight genes and rotavirus

has eleven. In comparison, humans have 20,000–25,000. Some viral genes

contain the code to make the structural proteins that form the virus

particle. Other genes make non-structural proteins found only in the

cells the virus infects.

All cells, and many viruses, produce proteins that are enzymes that drive chemical reactions. Some of these enzymes, called DNA polymerase and RNA polymerase,

make new copies of DNA and RNA. A virus's polymerase enzymes are often

much more efficient at making DNA and RNA than the equivalent enzymes

of the host cells, but viral RNA polymerase enzymes are error-prone, causing RNA viruses to mutate and form new strains.

In some species of RNA virus, the genes are not on a continuous

molecule of RNA, but are separated. The influenza virus, for example,

has eight separate genes made of RNA. When two different strains of

influenza virus infect the same cell, these genes can mix and produce

new strains of the virus in a process called reassortment.

Protein synthesis

Proteins are essential to life. Cells produce new protein molecules from amino acid

building blocks based on information coded in DNA. Each type of protein

is a specialist that usually only performs one function, so if a cell

needs to do something new, it must make a new protein. Viruses force the

cell to make new proteins that the cell does not need, but are needed

for the virus to reproduce. Protein synthesis consists of two major steps: transcription and translation.

Transcription is the process where information in DNA, called the genetic code, is used to produce RNA copies called messenger RNA (mRNA). These migrate through the cell and carry the code to ribosomes

where it is used to make proteins. This is called translation because

the protein's amino acid structure is determined by the mRNA's code.

Information is hence translated from the language of nucleic acids to

the language of amino acids.

Some nucleic acids of RNA viruses function directly as mRNA

without further modification. For this reason, these viruses are called

positive-sense RNA viruses.

In other RNA viruses, the RNA is a complementary copy of mRNA and these

viruses rely on the cell's or their own enzyme to make mRNA. These are

called negative-sense

RNA viruses. In viruses made from DNA, the method of mRNA production is

similar to that of the cell. The species of viruses called retroviruses

behave completely differently: they have RNA, but inside the host cell a

DNA copy of their RNA is made with the help of the enzyme reverse transcriptase. This DNA is then incorporated into the host's own DNA, and copied into mRNA by the cell's normal pathways.

Life-cycle

Life-cycle

of a typical virus (left to right); following infection of a cell by a

single virus, hundreds of offspring are released.

When a virus infects a cell, the virus forces it to make thousands

more viruses. It does this by making the cell copy the virus's DNA or

RNA, making viral proteins, which all assemble to form new virus

particles.

There are six basic, overlapping stages in the life cycle of viruses in living cells:

- Attachment is the binding of the virus to specific

molecules on the surface of the cell. This specificity restricts the

virus to a very limited type of cell. For example, the human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infects only human T cells, because its surface protein, gp120, can only react with CD4

and other molecules on the T cell's surface. Plant viruses can only

attach to plant cells and cannot infect animals. This mechanism has

evolved to favour those viruses that only infect cells in which they are

capable of reproducing.

- Penetration follows attachment; viruses penetrate the host cell by endocytosis or by fusion with the cell.

- Uncoating happens inside the cell when the viral capsid is

removed and destroyed by viral enzymes or host enzymes, thereby exposing

the viral nucleic acid.

- Replication of virus particles is the stage where a cell uses

viral messenger RNA in its protein synthesis systems to produce viral

proteins. The RNA or DNA synthesis abilities of the cell produce the

virus's DNA or RNA.

- Assembly takes place in the cell when the newly created viral proteins and nucleic acid combine to form hundreds of new virus particles.

- Release occurs when the new viruses escape or are released

from the cell. Most viruses achieve this by making the cells burst, a

process called lysis. Other viruses such as HIV are released more gently by a process called budding.

Effects on the host cell

Viruses have an extensive range of structural and biochemical effects on the host cell. These are called cytopathic effects.

Most virus infections eventually result in the death of the host cell.

The causes of death include cell lysis (bursting), alterations to the

cell's surface membrane and apoptosis (cell "suicide").

Often cell death is caused by cessation of its normal activity due to

proteins produced by the virus, not all of which are components of the

virus particle.

Some viruses cause no apparent changes to the infected cell. Cells in which the virus is latent (inactive) show few signs of infection and often function normally. This causes persistent infections and the virus is often dormant for many months or years. This is often the case with herpes viruses.

Some viruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus, often cause cells to proliferate without causing malignancy; but some other viruses, such as papillomavirus, are an established cause of cancer.

When a cell's DNA is damaged by a virus such that the cell cannot

repair itself, this often triggers apoptosis. One of the results of

apoptosis is destruction of the damaged DNA by the cell itself. Some

viruses have mechanisms to limit apoptosis so that the host cell does

not die before progeny viruses have been produced; HIV, for example, does this.

Viruses and diseases

There

are many ways in which viruses spread from host to host but each

species of virus uses only one or two. Many viruses that infect plants

are carried by organisms; such organisms are called vectors.

Some viruses that infect animals, including humans, are also spread by

vectors, usually blood-sucking insects, but direct transmission is more

common. Some virus infections, such as norovirus and rotavirus, are spread by contaminated food and water, by hands and communal objects, and by intimate contact with another infected person, while others are airborne (influenza virus). Viruses such as HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C are often transmitted by unprotected sex or contaminated hypodermic needles. To prevent infections and epidemics, it is important to know how each different kind of virus is spread.

In humans

Common human diseases caused by viruses include the common cold, influenza, chickenpox and cold sores. Serious diseases such as Ebola and AIDS are also caused by viruses. Many viruses cause little or no disease and are said to be "benign". The more harmful viruses are described as virulent.

Viruses cause different diseases depending on the types of cell that they infect.

Some viruses can cause lifelong or chronic infections where the viruses continue to reproduce in the body despite the host's defence mechanisms.

This is common in hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections.

People chronically infected with a virus are known as carriers. They

serve as important reservoirs of the virus.

Endemic

If the proportion of carriers in a given population reaches a given threshold, a disease is said to be endemic.

Before the advent of vaccination, infections with viruses were common

and outbreaks occurred regularly. In countries with a temperate climate,

viral diseases are usually seasonal. Poliomyelitis, caused by poliovirus often occurred in the summer months. By contrast colds, influenza and rotavirus infections are usually a problem during the winter months. Other viruses, such as measles virus, caused outbreaks regularly every third year.

In developing countries, viruses that cause respiratory and enteric

infections are common throughout the year. Viruses carried by insects

are a common cause of diseases in these settings. Zika and dengue viruses

for example are transmitted by the female Aedes mosquitoes, which bite

humans particularly during the mosquitoes' breeding season.

Pandemic and emergent

Origin

and evolution of (A) SARS-CoV (B) MERS-CoV, and (C) SARS-CoV-2 in

different hosts. All the viruses came from bats as coronavirus-related

viruses before mutating and adapting to intermediate hosts and then to

humans and causing the diseases

SARS,

MERS and

COVID-19.

Although viral pandemics are rare events, HIV—which evolved from viruses found in monkeys and chimpanzees—has been pandemic since at least the 1980s.

During the 20th century there were four pandemics caused by influenza

virus and those that occurred in 1918, 1957 and 1968 were severe. Before its eradication, smallpox was a cause of pandemics for more than 3,000 years. Throughout history, human migration has aided the spread of pandemic infections; first by sea and in modern times also by air.

With the exception of smallpox, most pandemics are caused by newly evolved viruses. These "emergent" viruses are usually mutants of less harmful viruses that have circulated previously either in humans or in other animals.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) are caused by new types of coronaviruses. Other coronaviruses are known to cause mild infections in humans,

so the virulence and rapid spread of SARS infections—that by July 2003

had caused around 8,000 cases and 800 deaths—was unexpected and most

countries were not prepared.

A related coronavirus emerged in Wuhan, China in November 2019 and spread rapidly around the world. Thought to have originated in bats and subsequently named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, infections with the virus cause a disease called COVID-19, that varies in severity from mild to deadly, and led to a pandemic in 2020. Restrictions unprecedented in peacetime have been placed on international travel, and curfews imposed in several major cities worldwide.

In plants

Peppers infected by mild mottle virus

There are many types of plant virus, but often they only cause a decrease in yield,

and it is not economically viable to try to control them. Plant viruses

are frequently spread from plant to plant by organisms called "vectors". These are normally insects, but some fungi, nematode worms and single-celled organisms

have also been shown to be vectors. When control of plant virus

infections is considered economical (perennial fruits, for example)

efforts are concentrated on killing the vectors and removing alternate

hosts such as weeds. Plant viruses are harmless to humans and other animals because they can only reproduce in living plant cells.

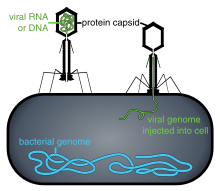

Bacteriophages

The structure of a typical bacteriophage

Bacteriophages are viruses that infect bacteria and archaea. They are important in marine ecology:

as the infected bacteria burst, carbon compounds are released back into

the environment, which stimulates fresh organic growth. Bacteriophages

are useful in scientific research because they are harmless to humans

and can be studied easily. These viruses can be a problem in industries

that produce food and drugs by fermentation

and depend on healthy bacteria. Some bacterial infections are becoming

difficult to control with antibiotics, so there is a growing interest in

the use of bacteriophages to treat infections in humans.

Host resistance

Innate immunity of animals

Animals, including humans, have many natural defences against

viruses. Some are non-specific and protect against many viruses

regardless of the type. This innate

immunity is not improved by repeated exposure to viruses and does not

retain a "memory" of the infection. The skin of animals, particularly

its surface, which is made from dead cells, prevents many types of

viruses from infecting the host. The acidity of the contents of the

stomach destroys many viruses that have been swallowed. When a virus

overcomes these barriers and enters the host, other innate defences

prevent the spread of infection in the body. A special hormone called interferon

is produced by the body when viruses are present, and this stops the

viruses from reproducing by killing the infected cells and their close

neighbours. Inside cells, there are enzymes that destroy the RNA of

viruses. This is called RNA interference. Some blood cells engulf and destroy other virus-infected cells.

Adaptive immunity of animals

Two rotavirus particles: the one on the right is coated with antibodies which stop its attaching to cells and infecting them

Specific immunity to viruses develops over time and white blood cells called lymphocytes play a central role. Lymphocytes retain a "memory" of virus infections and produce many special molecules called antibodies.

These antibodies attach to viruses and stop the virus from infecting

cells. Antibodies are highly selective and attack only one type of

virus. The body makes many different antibodies, especially during the

initial infection. After the infection subsides, some antibodies remain

and continue to be produced, usually giving the host lifelong immunity

to the virus.

Plant resistance

Plants have elaborate and effective defence mechanisms against viruses. One of the most effective is the presence of so-called resistance (R) genes.

Each R gene confers resistance to a particular virus by triggering

localised areas of cell death around the infected cell, which can often

be seen with the unaided eye as large spots. This stops the infection

from spreading. RNA interference is also an effective defence in plants. When they are infected, plants often produce natural disinfectants that destroy viruses, such as salicylic acid, nitric oxide and reactive oxygen molecules.

Resistance to bacteriophages

The

major way bacteria defend themselves from bacteriophages is by

producing enzymes which destroy foreign DNA. These enzymes, called restriction endonucleases, cut up the viral DNA that bacteriophages inject into bacterial cells.

Prevention and treatment of viral disease

Vaccines

The structure of DNA showing the position of the nucleosides and the phosphorus atoms that form the "backbone" of the molecule

Vaccines simulate a natural infection and its associated immune

response, but do not cause the disease. Their use has resulted in the

eradication of smallpox and a dramatic decline in illness and death caused by infections such as polio, measles, mumps and rubella. Vaccines are available to prevent over fourteen viral infections of humans and more are used to prevent viral infections of animals. Vaccines may consist of either live or killed viruses. Live vaccines contain weakened forms of the virus, but these vaccines can be dangerous when given to people with weak immunity. In these people, the weakened virus can cause the original disease.

Biotechnology and genetic engineering techniques are used to produce

"designer" vaccines that only have the capsid proteins of the virus.

Hepatitis B vaccine is an example of this type of vaccine. These vaccines are safer because they can never cause the disease.

Antiviral drugs

The structure of the DNA base

guanosine and the antiviral drug

aciclovir which functions by mimicking it

Since the mid-1980s, the development of antiviral drugs has increased rapidly, mainly driven by the AIDS pandemic. Antiviral drugs are often nucleoside analogues, which masquerade as DNA building blocks (nucleosides).

When the replication of virus DNA begins, some of the fake building

blocks are used. This prevents DNA replication because the drugs lack

the essential features that allow the formation of a DNA chain. When DNA

production stops the virus can no longer reproduce. Examples of nucleoside analogues are aciclovir for herpes virus infections and lamivudine for HIV and hepatitis B virus infections. Aciclovir is one of the oldest and most frequently prescribed antiviral drugs.

Other antiviral drugs target different stages of the viral life cycle. HIV is dependent on an enzyme called the HIV-1 protease for the virus to become infectious. There is a class of drugs called protease inhibitors, which bind to this enzyme and stop it from functioning.

Hepatitis C is caused by an RNA virus. In 80% of those infected, the disease becomes chronic,

and they remain infectious for the rest of their lives unless they are

treated. There is an effective treatment that uses the nucleoside

analogue drug ribavirin.

Treatments for chronic carriers of the hepatitis B virus have been

developed by a similar strategy, using lamivudine and other anti-viral

drugs. In both diseases, the drugs stop the virus from reproducing and

the interferon kills any remaining infected cells.

HIV infections are usually treated with a combination of

antiviral drugs, each targeting a different stage in the virus's

life-cycle. There are drugs that prevent the virus from attaching to

cells, others that are nucleoside analogues and some poison the virus's

enzymes that it needs to reproduce. The success of these drugs is proof

of the importance of knowing how viruses reproduce.

Role in ecology

Viruses are the most abundant biological entity in aquatic environments; one teaspoon of seawater contains about ten million viruses, and they are essential to the regulation of saltwater and freshwater ecosystems. Most are bacteriophages,

which are harmless to plants and animals. They infect and destroy the

bacteria in aquatic microbial communities and this is the most important

mechanism of recycling carbon in the marine environment. The organic

molecules released from the bacterial cells by the viruses stimulate

fresh bacterial and algal growth.

Microorganisms constitute more than 90% of the biomass in the

sea. It is estimated that viruses kill approximately 20% of this biomass

each day and that there are fifteen times as many viruses in the oceans

as there are bacteria and archaea. They are mainly responsible for the

rapid destruction of harmful algal blooms, which often kill other marine life.

The number of viruses in the oceans decreases further offshore and deeper into the water, where there are fewer host organisms.

Their effects are far-reaching; by increasing the amount of

respiration in the oceans, viruses are indirectly responsible for

reducing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by approximately

3 gigatonnes of carbon per year.

Marine mammals are also susceptible to viral infections. In 1988 and 2002, thousands of harbour seals were killed in Europe by phocine distemper virus.

Many other viruses, including caliciviruses, herpesviruses,

adenoviruses and parvoviruses, circulate in marine mammal populations.