From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Machine learning (ML) is the study of computer algorithms that improve automatically through experience and by the use of data. It is seen as a part of artificial intelligence. Machine learning algorithms build a model based on sample data, known as "training data", in order to make predictions or decisions without being explicitly programmed to do so. Machine learning algorithms are used in a wide variety of applications, such as in medicine, email filtering, speech recognition, and computer vision, where it is difficult or unfeasible to develop conventional algorithms to perform the needed tasks.

A subset of machine learning is closely related to computational statistics, which focuses on making predictions using computers; but not all machine learning is statistical learning. The study of mathematical optimization delivers methods, theory and application domains to the field of machine learning. Data mining is a related field of study, focusing on exploratory data analysis through unsupervised learning. In its application across business problems, machine learning is also referred to as predictive analytics.

Overview

Machine

learning involves computers discovering how they can perform tasks

without being explicitly programmed to do so. It involves computers

learning from data provided so that they carry out certain tasks. For

simple tasks assigned to computers, it is possible to program algorithms

telling the machine how to execute all steps required to solve the

problem at hand; on the computer's part, no learning is needed. For more

advanced tasks, it can be challenging for a human to manually create

the needed algorithms. In practice, it can turn out to be more effective

to help the machine develop its own algorithm, rather than having human

programmers specify every needed step.

The discipline of machine learning employs various approaches to

teach computers to accomplish tasks where no fully satisfactory

algorithm is available. In cases where vast numbers of potential answers

exist, one approach is to label some of the correct answers as valid.

This can then be used as training data for the computer to improve the

algorithm(s) it uses to determine correct answers. For example, to train

a system for the task of digital character recognition, the MNIST dataset of handwritten digits has often been used.

History and relationships to other fields

The term machine learning was coined in 1959 by Arthur Samuel, an American IBMer and pioneer in the field of computer gaming and artificial intelligence.

A representative book of the machine learning research during the 1960s

was the Nilsson's book on Learning Machines, dealing mostly with

machine learning for pattern classification. Interest related to pattern recognition continued into the 1970s, as described by Duda and Hart in 1973. In 1981 a report was given on using teaching strategies so that a neural network learns to recognize 40 characters (26 letters, 10 digits, and 4 special symbols) from a computer terminal.

Tom M. Mitchell

provided a widely quoted, more formal definition of the algorithms

studied in the machine learning field: "A computer program is said to

learn from experience E with respect to some class of tasks T and performance measure P if its performance at tasks in T, as measured by P, improves with experience E." This definition of the tasks in which machine learning is concerned offers a fundamentally operational definition rather than defining the field in cognitive terms. This follows Alan Turing's proposal in his paper "Computing Machinery and Intelligence",

in which the question "Can machines think?" is replaced with the

question "Can machines do what we (as thinking entities) can do?".

Modern day machine learning has two objectives, one is to

classify data based on models which have been developed, the other

purpose is to make predictions for future outcomes based on these

models. A hypothetical algorithm specific to classifying data may use

computer vision of moles coupled with supervised learning in order to

train it to classify the cancerous moles. Where as, a machine learning

algorithm for stock trading may inform the trader of future potential

predictions.

Artificial intelligence

Machine learning as subfield of AI

Part of machine learning as subfield of AI or part of AI as subfield of machine learning

As a scientific endeavor, machine learning grew out of the quest for artificial intelligence. In the early days of AI as an academic discipline,

some researchers were interested in having machines learn from data.

They attempted to approach the problem with various symbolic methods, as

well as what was then termed "neural networks"; these were mostly perceptrons and other models that were later found to be reinventions of the generalized linear models of statistics. Probabilistic reasoning was also employed, especially in automated medical diagnosis.

However, an increasing emphasis on the logical, knowledge-based approach

caused a rift between AI and machine learning. Probabilistic systems

were plagued by theoretical and practical problems of data acquisition

and representation. By 1980, expert systems had come to dominate AI, and statistics was out of favor. Work on symbolic/knowledge-based learning did continue within AI, leading to inductive logic programming, but the more statistical line of research was now outside the field of AI proper, in pattern recognition and information retrieval. Neural networks research had been abandoned by AI and computer science around the same time. This line, too, was continued outside the AI/CS field, as "connectionism", by researchers from other disciplines including Hopfield, Rumelhart and Hinton. Their main success came in the mid-1980s with the reinvention of backpropagation.

Machine learning (ML), reorganized as a separate field, started

to flourish in the 1990s. The field changed its goal from achieving

artificial intelligence to tackling solvable problems of a practical

nature. It shifted focus away from the symbolic approaches it had inherited from AI, and toward methods and models borrowed from statistics and probability theory.

As of 2020, many sources continue to assert that machine learning remains a subfield of AI.

The main disagreement is whether all of ML is part of AI, as this would

mean that anyone using ML could claim they are using AI. Others have

the view that not all of ML is part of AI where only an 'intelligent' subset of ML is part of AI.

The question to what is the difference between ML and AI is answered by Judea Pearl in The Book of Why.

Accordingly ML learns and predicts based on passive observations,

whereas AI implies an agent interacting with the environment to learn

and take actions that maximize its chance of successfully achieving its

goals.

Data mining

Machine learning and data mining often employ the same methods and overlap significantly, but while machine learning focuses on prediction, based on known properties learned from the training data, data mining focuses on the discovery of (previously) unknown properties in the data (this is the analysis step of knowledge discovery

in databases). Data mining uses many machine learning methods, but with

different goals; on the other hand, machine learning also employs data

mining methods as "unsupervised learning" or as a preprocessing step to

improve learner accuracy. Much of the confusion between these two

research communities (which do often have separate conferences and

separate journals, ECML PKDD

being a major exception) comes from the basic assumptions they work

with: in machine learning, performance is usually evaluated with respect

to the ability to reproduce known knowledge, while in knowledge discovery and data mining (KDD) the key task is the discovery of previously unknown

knowledge. Evaluated with respect to known knowledge, an uninformed

(unsupervised) method will easily be outperformed by other supervised

methods, while in a typical KDD task, supervised methods cannot be used

due to the unavailability of training data.

Optimization

Machine learning also has intimate ties to optimization: many learning problems are formulated as minimization of some loss function

on a training set of examples. Loss functions express the discrepancy

between the predictions of the model being trained and the actual

problem instances (for example, in classification, one wants to assign a

label to instances, and models are trained to correctly predict the

pre-assigned labels of a set of examples).

Generalization

The

difference between optimization and machine learning arises from the

goal of generalization: while optimization algorithms can minimize the

loss on a training set, machine learning is concerned with minimizing

the loss on unseen samples. Characterizing the generalization of various

learning algorithms is an active topic of current research, especially

for deep learning algorithms.

Statistics

Machine learning and statistics are closely related fields in terms of methods, but distinct in their principal goal: statistics draws population inferences from a sample, while machine learning finds generalizable predictive patterns. According to Michael I. Jordan, the ideas of machine learning, from methodological principles to theoretical tools, have had a long pre-history in statistics. He also suggested the term data science as a placeholder to call the overall field.

Leo Breiman distinguished two statistical modeling paradigms: data model and algorithmic model, wherein "algorithmic model" means more or less the machine learning algorithms like Random forest.

Some statisticians have adopted methods from machine learning, leading to a combined field that they call statistical learning.

Theory

A core objective of a learner is to generalize from its experience.

Generalization in this context is the ability of a learning machine to

perform accurately on new, unseen examples/tasks after having

experienced a learning data set. The training examples come from some

generally unknown probability distribution (considered representative of

the space of occurrences) and the learner has to build a general model

about this space that enables it to produce sufficiently accurate

predictions in new cases.

The computational analysis of machine learning algorithms and their performance is a branch of theoretical computer science known as computational learning theory.

Because training sets are finite and the future is uncertain, learning

theory usually does not yield guarantees of the performance of

algorithms. Instead, probabilistic bounds on the performance are quite

common. The bias–variance decomposition is one way to quantify generalization error.

For the best performance in the context of generalization, the

complexity of the hypothesis should match the complexity of the function

underlying the data. If the hypothesis is less complex than the

function, then the model has under fitted the data. If the complexity of

the model is increased in response, then the training error decreases.

But if the hypothesis is too complex, then the model is subject to overfitting and generalization will be poorer.

In addition to performance bounds, learning theorists study the

time complexity and feasibility of learning. In computational learning

theory, a computation is considered feasible if it can be done in polynomial time. There are two kinds of time complexity

results. Positive results show that a certain class of functions can be

learned in polynomial time. Negative results show that certain classes

cannot be learned in polynomial time.

Approaches

Machine learning approaches are traditionally divided into three broad

categories, depending on the nature of the "signal" or "feedback"

available to the learning system:

- Supervised learning:

The computer is presented with example inputs and their desired

outputs, given by a "teacher", and the goal is to learn a general rule

that maps inputs to outputs.

- Unsupervised learning:

No labels are given to the learning algorithm, leaving it on its own to

find structure in its input. Unsupervised learning can be a goal in

itself (discovering hidden patterns in data) or a means towards an end (feature learning).

- Reinforcement learning: A computer program interacts with a dynamic environment in which it must perform a certain goal (such as driving a vehicle

or playing a game against an opponent). As it navigates its problem

space, the program is provided feedback that's analogous to rewards,

which it tries to maximize.

Supervised learning

A

support-vector machine is a supervised learning model that divides the data into regions separated by a

linear boundary. Here, the linear boundary divides the black circles from the white.

Supervised learning algorithms build a mathematical model of a set of

data that contains both the inputs and the desired outputs. The data is known as training data,

and consists of a set of training examples. Each training example has

one or more inputs and the desired output, also known as a supervisory

signal. In the mathematical model, each training example is represented

by an array or vector, sometimes called a feature vector, and the training data is represented by a matrix. Through iterative optimization of an objective function, supervised learning algorithms learn a function that can be used to predict the output associated with new inputs.

An optimal function will allow the algorithm to correctly determine the

output for inputs that were not a part of the training data. An

algorithm that improves the accuracy of its outputs or predictions over

time is said to have learned to perform that task.

Types of supervised learning algorithms include active learning, classification and regression.

Classification algorithms are used when the outputs are restricted to a

limited set of values, and regression algorithms are used when the

outputs may have any numerical value within a range. As an example, for a

classification algorithm that filters emails, the input would be an

incoming email, and the output would be the name of the folder in which

to file the email.

Similarity learning

is an area of supervised machine learning closely related to regression

and classification, but the goal is to learn from examples using a

similarity function that measures how similar or related two objects

are. It has applications in ranking, recommendation systems, visual identity tracking, face verification, and speaker verification.

Unsupervised learning

Unsupervised learning algorithms take a set of data that contains

only inputs, and find structure in the data, like grouping or clustering

of data points. The algorithms, therefore, learn from test data that

has not been labeled, classified or categorized. Instead of responding

to feedback, unsupervised learning algorithms identify commonalities in

the data and react based on the presence or absence of such

commonalities in each new piece of data. A central application of

unsupervised learning is in the field of density estimation in statistics, such as finding the probability density function. Though unsupervised learning encompasses other domains involving summarizing and explaining data features.

Cluster analysis is the assignment of a set of observations into subsets (called clusters)

so that observations within the same cluster are similar according to

one or more predesignated criteria, while observations drawn from

different clusters are dissimilar. Different clustering techniques make

different assumptions on the structure of the data, often defined by

some similarity metric and evaluated, for example, by internal compactness, or the similarity between members of the same cluster, and separation, the difference between clusters. Other methods are based on estimated density and graph connectivity.

Semi-supervised learning

Semi-supervised learning falls between unsupervised learning (without any labeled training data) and supervised learning

(with completely labeled training data). Some of the training examples

are missing training labels, yet many machine-learning researchers have

found that unlabeled data, when used in conjunction with a small amount

of labeled data, can produce a considerable improvement in learning

accuracy.

In weakly supervised learning,

the training labels are noisy, limited, or imprecise; however, these

labels are often cheaper to obtain, resulting in larger effective

training sets.

Reinforcement learning

Reinforcement learning is an area of machine learning concerned with how software agents ought to take actions

in an environment so as to maximize some notion of cumulative reward.

Due to its generality, the field is studied in many other disciplines,

such as game theory, control theory, operations research, information theory, simulation-based optimization, multi-agent systems, swarm intelligence, statistics and genetic algorithms. In machine learning, the environment is typically represented as a Markov decision process (MDP). Many reinforcement learning algorithms use dynamic programming techniques.

Reinforcement learning algorithms do not assume knowledge of an exact

mathematical model of the MDP, and are used when exact models are

infeasible. Reinforcement learning algorithms are used in autonomous

vehicles or in learning to play a game against a human opponent.

Dimensionality Reduction

The

Dimensionality reduction is a process of reducing the number of random

variables under the consideration by obtaining a set of principal

variables.

In other words, it is a process of reducing the dimension of your

feature set also called no of features. Most of the dimensionality

reduction techniques can be considered as either feature elimination or

extraction.

One of the popular method of dimensionality reduction is called as

principal component analysis.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

The PCA involves changing higher dimensional data (eg. 3D) to a

smaller space (eg. 2D). This results in a smaller dimension of data, (2D

instead of 3D) while keeping all original variables in the model

without changing the data.

Other types

Other

approaches have been developed which don't fit neatly into this

three-fold categorisation, and sometimes more than one is used by the

same machine learning system. For example topic modeling, meta learning.

As of 2020, deep learning has become the dominant approach for much ongoing work in the field of machine learning.

Self learning

Self-learning as a machine learning paradigm was introduced in 1982 along with a neural network capable of self-learning named crossbar adaptive array (CAA).

It is a learning with no external rewards and no external teacher

advice. The CAA self-learning algorithm computes, in a crossbar fashion,

both decisions about actions and emotions (feelings) about consequence

situations. The system is driven by the interaction between cognition

and emotion.

The self-learning algorithm updates a memory matrix W =||w(a,s)|| such

that in each iteration executes the following machine learning routine:

In situation s perform an action a;

Receive consequence situation s’;

Compute emotion of being in consequence situation v(s’);

Update crossbar memory w’(a,s) = w(a,s) + v(s’).

It is a system with only one input, situation s, and only one output,

action (or behavior) a. There is neither a separate reinforcement input

nor an advice input from the environment. The backpropagated value

(secondary reinforcement) is the emotion toward the consequence

situation. The CAA exists in two environments, one is the behavioral

environment where it behaves, and the other is the genetic environment,

wherefrom it initially and only once receives initial emotions about

situations to be encountered in the behavioral environment. After

receiving the genome (species) vector from the genetic environment, the

CAA learns a goal-seeking behavior, in an environment that contains both

desirable and undesirable situations.

Feature learning

Several learning algorithms aim at discovering better representations of the inputs provided during training. Classic examples include principal components analysis

and cluster analysis. Feature learning algorithms, also called

representation learning algorithms, often attempt to preserve the

information in their input but also transform it in a way that makes it

useful, often as a pre-processing step before performing classification

or predictions. This technique allows reconstruction of the inputs

coming from the unknown data-generating distribution, while not being

necessarily faithful to configurations that are implausible under that

distribution. This replaces manual feature engineering, and allows a machine to both learn the features and use them to perform a specific task.

Feature learning can be either supervised or unsupervised. In

supervised feature learning, features are learned using labeled input

data. Examples include artificial neural networks, multilayer perceptrons, and supervised dictionary learning. In unsupervised feature learning, features are learned with unlabeled input data. Examples include dictionary learning, independent component analysis, autoencoders, matrix factorization and various forms of clustering.

Manifold learning algorithms attempt to do so under the constraint that the learned representation is low-dimensional. Sparse coding

algorithms attempt to do so under the constraint that the learned

representation is sparse, meaning that the mathematical model has many

zeros. Multilinear subspace learning algorithms aim to learn low-dimensional representations directly from tensor representations for multidimensional data, without reshaping them into higher-dimensional vectors. Deep learning

algorithms discover multiple levels of representation, or a hierarchy

of features, with higher-level, more abstract features defined in terms

of (or generating) lower-level features. It has been argued that an

intelligent machine is one that learns a representation that

disentangles the underlying factors of variation that explain the

observed data.

Feature learning is motivated by the fact that machine learning

tasks such as classification often require input that is mathematically

and computationally convenient to process. However, real-world data such

as images, video, and sensory data has not yielded to attempts to

algorithmically define specific features. An alternative is to discover

such features or representations through examination, without relying on

explicit algorithms.

Sparse dictionary learning

Sparse dictionary learning is a feature learning method where a training example is represented as a linear combination of basis functions, and is assumed to be a sparse matrix. The method is strongly NP-hard and difficult to solve approximately. A popular heuristic method for sparse dictionary learning is the K-SVD

algorithm. Sparse dictionary learning has been applied in several

contexts. In classification, the problem is to determine the class to

which a previously unseen training example belongs. For a dictionary

where each class has already been built, a new training example is

associated with the class that is best sparsely represented by the

corresponding dictionary. Sparse dictionary learning has also been

applied in image de-noising. The key idea is that a clean image patch can be sparsely represented by an image dictionary, but the noise cannot.

Anomaly detection

In data mining,

anomaly detection, also known as outlier detection, is the

identification of rare items, events or observations which raise

suspicions by differing significantly from the majority of the data. Typically, the anomalous items represent an issue such as bank fraud, a structural defect, medical problems or errors in a text. Anomalies are referred to as outliers, novelties, noise, deviations and exceptions.

In particular, in the context of abuse and network intrusion

detection, the interesting objects are often not rare objects, but

unexpected bursts of inactivity. This pattern does not adhere to the

common statistical definition of an outlier as a rare object, and many

outlier detection methods (in particular, unsupervised algorithms) will

fail on such data unless it has been aggregated appropriately. Instead, a

cluster analysis algorithm may be able to detect the micro-clusters

formed by these patterns.

Three broad categories of anomaly detection techniques exist.

Unsupervised anomaly detection techniques detect anomalies in an

unlabeled test data set under the assumption that the majority of the

instances in the data set are normal, by looking for instances that seem

to fit least to the remainder of the data set. Supervised anomaly

detection techniques require a data set that has been labeled as

"normal" and "abnormal" and involves training a classifier (the key

difference to many other statistical classification problems is the

inherently unbalanced nature of outlier detection). Semi-supervised

anomaly detection techniques construct a model representing normal

behavior from a given normal training data set and then test the

likelihood of a test instance to be generated by the model.

Robot learning

In developmental robotics, robot learning

algorithms generate their own sequences of learning experiences, also

known as a curriculum, to cumulatively acquire new skills through

self-guided exploration and social interaction with humans. These robots

use guidance mechanisms such as active learning, maturation, motor synergies and imitation.

Association rules

Association rule learning is a rule-based machine learning

method for discovering relationships between variables in large

databases. It is intended to identify strong rules discovered in

databases using some measure of "interestingness".

Rule-based machine learning is a general term for any machine

learning method that identifies, learns, or evolves "rules" to store,

manipulate or apply knowledge. The defining characteristic of a

rule-based machine learning algorithm is the identification and

utilization of a set of relational rules that collectively represent the

knowledge captured by the system. This is in contrast to other machine

learning algorithms that commonly identify a singular model that can be

universally applied to any instance in order to make a prediction. Rule-based machine learning approaches include learning classifier systems, association rule learning, and artificial immune systems.

Based on the concept of strong rules, Rakesh Agrawal, Tomasz Imieliński

and Arun Swami introduced association rules for discovering

regularities between products in large-scale transaction data recorded

by point-of-sale (POS) systems in supermarkets. For example, the rule  found in the sales data of a supermarket would indicate that if a

customer buys onions and potatoes together, they are likely to also buy

hamburger meat. Such information can be used as the basis for decisions

about marketing activities such as promotional pricing or product placements. In addition to market basket analysis, association rules are employed today in application areas including Web usage mining, intrusion detection, continuous production, and bioinformatics. In contrast with sequence mining, association rule learning typically does not consider the order of items either within a transaction or across transactions.

found in the sales data of a supermarket would indicate that if a

customer buys onions and potatoes together, they are likely to also buy

hamburger meat. Such information can be used as the basis for decisions

about marketing activities such as promotional pricing or product placements. In addition to market basket analysis, association rules are employed today in application areas including Web usage mining, intrusion detection, continuous production, and bioinformatics. In contrast with sequence mining, association rule learning typically does not consider the order of items either within a transaction or across transactions.

Learning classifier systems (LCS) are a family of rule-based

machine learning algorithms that combine a discovery component,

typically a genetic algorithm, with a learning component, performing either supervised learning, reinforcement learning, or unsupervised learning. They seek to identify a set of context-dependent rules that collectively store and apply knowledge in a piecewise manner in order to make predictions.

Inductive logic programming (ILP) is an approach to rule-learning using logic programming

as a uniform representation for input examples, background knowledge,

and hypotheses. Given an encoding of the known background knowledge and a

set of examples represented as a logical database of facts, an ILP

system will derive a hypothesized logic program that entails all positive and no negative examples. Inductive programming

is a related field that considers any kind of programming language for

representing hypotheses (and not only logic programming), such as functional programs.

Inductive logic programming is particularly useful in bioinformatics and natural language processing. Gordon Plotkin and Ehud Shapiro laid the initial theoretical foundation for inductive machine learning in a logical setting.

Shapiro built their first implementation (Model Inference System) in

1981: a Prolog program that inductively inferred logic programs from

positive and negative examples. The term inductive here refers to philosophical induction, suggesting a theory to explain observed facts, rather than mathematical induction, proving a property for all members of a well-ordered set.

Models

Performing machine learning involves creating a model,

which is trained on some training data and then can process additional

data to make predictions. Various types of models have been used and

researched for machine learning systems.

Artificial neural networks

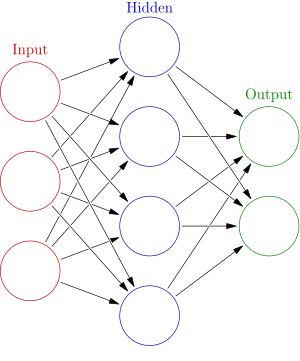

An artificial neural network is an interconnected group of nodes, akin to the vast network of

neurons in a

brain. Here, each circular node represents an

artificial neuron and an arrow represents a connection from the output of one artificial neuron to the input of another.

Artificial neural networks (ANNs), or connectionist systems, are computing systems vaguely inspired by the biological neural networks that constitute animal brains.

Such systems "learn" to perform tasks by considering examples,

generally without being programmed with any task-specific rules.

An ANN is a model based on a collection of connected units or nodes called "artificial neurons", which loosely model the neurons in a biological brain. Each connection, like the synapses in a biological brain,

can transmit information, a "signal", from one artificial neuron to

another. An artificial neuron that receives a signal can process it and

then signal additional artificial neurons connected to it. In common ANN

implementations, the signal at a connection between artificial neurons

is a real number,

and the output of each artificial neuron is computed by some non-linear

function of the sum of its inputs. The connections between artificial

neurons are called "edges". Artificial neurons and edges typically have a

weight

that adjusts as learning proceeds. The weight increases or decreases

the strength of the signal at a connection. Artificial neurons may have a

threshold such that the signal is only sent if the aggregate signal

crosses that threshold. Typically, artificial neurons are aggregated

into layers. Different layers may perform different kinds of

transformations on their inputs. Signals travel from the first layer

(the input layer) to the last layer (the output layer), possibly after

traversing the layers multiple times.

The original goal of the ANN approach was to solve problems in the same way that a human brain would. However, over time, attention moved to performing specific tasks, leading to deviations from biology. Artificial neural networks have been used on a variety of tasks, including computer vision, speech recognition, machine translation, social network filtering, playing board and video games and medical diagnosis.

Deep learning

consists of multiple hidden layers in an artificial neural network.

This approach tries to model the way the human brain processes light and

sound into vision and hearing. Some successful applications of deep

learning are computer vision and speech recognition.

Decision trees

Decision tree learning uses a decision tree as a predictive model

to go from observations about an item (represented in the branches) to

conclusions about the item's target value (represented in the leaves).

It is one of the predictive modeling approaches used in statistics, data

mining, and machine learning. Tree models where the target variable can

take a discrete set of values are called classification trees; in these

tree structures, leaves represent class labels and branches represent conjunctions of features that lead to those class labels. Decision trees where the target variable can take continuous values (typically real numbers)

are called regression trees. In decision analysis, a decision tree can

be used to visually and explicitly represent decisions and decision making. In data mining, a decision tree describes data, but the resulting classification tree can be an input for decision making.

Support-vector machines

Support-vector machines (SVMs), also known as support-vector networks, are a set of related supervised learning

methods used for classification and regression. Given a set of training

examples, each marked as belonging to one of two categories, an SVM

training algorithm builds a model that predicts whether a new example

falls into one category or the other. An SVM training algorithm is a non-probabilistic, binary, linear classifier, although methods such as Platt scaling

exist to use SVM in a probabilistic classification setting. In addition

to performing linear classification, SVMs can efficiently perform a

non-linear classification using what is called the kernel trick, implicitly mapping their inputs into high-dimensional feature spaces.

Illustration of linear regression on a data set.

Regression analysis

Regression analysis encompasses a large variety of statistical

methods to estimate the relationship between input variables and their

associated features. Its most common form is linear regression, where a single line is drawn to best fit the given data according to a mathematical criterion such as ordinary least squares. The latter is often extended by regularization (mathematics) methods to mitigate overfitting and bias, as in ridge regression. When dealing with non-linear problems, go-to models include polynomial regression (for example, used for trendline fitting in Microsoft Excel), logistic regression (often used in statistical classification) or even kernel regression, which introduces non-linearity by taking advantage of the kernel trick to implicitly map input variables to higher-dimensional space.

Bayesian networks

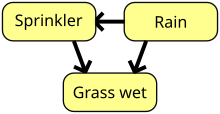

A

simple Bayesian network. Rain influences whether the sprinkler is

activated, and both rain and the sprinkler influence whether the grass

is wet.

A Bayesian network, belief network, or directed acyclic graphical model is a probabilistic graphical model that represents a set of random variables and their conditional independence with a directed acyclic graph

(DAG). For example, a Bayesian network could represent the

probabilistic relationships between diseases and symptoms. Given

symptoms, the network can be used to compute the probabilities of the

presence of various diseases. Efficient algorithms exist that perform inference and learning. Bayesian networks that model sequences of variables, like speech signals or protein sequences, are called dynamic Bayesian networks. Generalizations of Bayesian networks that can represent and solve decision problems under uncertainty are called influence diagrams.

Genetic algorithms

A genetic algorithm (GA) is a search algorithm and heuristic technique that mimics the process of natural selection, using methods such as mutation and crossover to generate new genotypes

in the hope of finding good solutions to a given problem. In machine

learning, genetic algorithms were used in the 1980s and 1990s. Conversely, machine learning techniques have been used to improve the performance of genetic and evolutionary algorithms.

Training models

Usually,

machine learning models require a lot of data in order for them to

perform well. Usually, when training a machine learning model, one needs

to collect a large, representative sample of data from a training set.

Data from the training set can be as varied as a corpus of text, a

collection of images, and data collected from individual users of a

service. Overfitting

is something to watch out for when training a machine learning model.

Trained models derived from biased data can result in skewed or

undesired predictions. Algorithmic bias is a potential result from data not fully prepared for training.

Federated learning

Federated learning is an adapted form of distributed artificial intelligence

to training machine learning models that decentralizes the training

process, allowing for users' privacy to be maintained by not needing to

send their data to a centralized server. This also increases efficiency

by decentralizing the training process to many devices. For example, Gboard

uses federated machine learning to train search query prediction models

on users' mobile phones without having to send individual searches back

to Google.

Applications

There are many applications for machine learning, including:

In 2006, the media-services provider Netflix held the first "Netflix Prize"

competition to find a program to better predict user preferences and

improve the accuracy of its existing Cinematch movie recommendation

algorithm by at least 10%. A joint team made up of researchers from AT&T Labs-Research in collaboration with the teams Big Chaos and Pragmatic Theory built an ensemble model to win the Grand Prize in 2009 for $1 million.

Shortly after the prize was awarded, Netflix realized that viewers'

ratings were not the best indicators of their viewing patterns

("everything is a recommendation") and they changed their recommendation

engine accordingly.

In 2010 The Wall Street Journal wrote about the firm Rebellion Research

and their use of machine learning to predict the financial crisis. In 2012, co-founder of Sun Microsystems, Vinod Khosla,

predicted that 80% of medical doctors' jobs would be lost in the next

two decades to automated machine learning medical diagnostic software.

In 2014, it was reported that a machine learning algorithm had been

applied in the field of art history to study fine art paintings and that

it may have revealed previously unrecognized influences among artists. In 2019 Springer Nature published the first research book created using machine learning. In 2020, machine learning technology was used to help make diagnoses and aid researchers in developing a cure for COVID-19. Machine learning is recently applied to predict the green behavior of human-being.

Recently, machine learning technology is also applied to optimise

smartphone's performance and thermal behaviour based on the user's

interaction with the phone.

Limitations

Although

machine learning has been transformative in some fields,

machine-learning programs often fail to deliver expected results.

Reasons for this are numerous: lack of (suitable) data, lack of access

to the data, data bias, privacy problems, badly chosen tasks and

algorithms, wrong tools and people, lack of resources, and evaluation

problems.

In 2018, a self-driving car from Uber failed to detect a pedestrian, who was killed after a collision. Attempts to use machine learning in healthcare with the IBM Watson system failed to deliver even after years of time and billions of dollars invested.

Machine learning has been used as a strategy to update the

evidence related to systematic review and increased reviewer burden

related to the growth of biomedical literature. While it has improved

with training sets, it has not yet developed sufficiently to reduce the

workload burden without limiting the necessary sensitivity for the

findings research themselves.

Bias

Machine learning approaches in particular can suffer from different

data biases. A machine learning system trained specifically on current

customers may not be able to predict the needs of new customer groups

that are not represented in the training data. When trained on man-made

data, machine learning is likely to pick up the constitutional and

unconscious biases already present in society. Language models learned from data have been shown to contain human-like biases. Machine learning systems used for criminal risk assessment have been found to be biased against black people. In 2015, Google photos would often tag black people as gorillas,

and in 2018 this still was not well resolved, but Google reportedly was

still using the workaround to remove all gorillas from the training

data, and thus was not able to recognize real gorillas at all. Similar issues with recognizing non-white people have been found in many other systems. In 2016, Microsoft tested a chatbot that learned from Twitter, and it quickly picked up racist and sexist language. Because of such challenges, the effective use of machine learning may take longer to be adopted in other domains. Concern for fairness

in machine learning, that is, reducing bias in machine learning and

propelling its use for human good is increasingly expressed by

artificial intelligence scientists, including Fei-Fei Li,

who reminds engineers that "There’s nothing artificial about AI...It’s

inspired by people, it’s created by people, and—most importantly—it

impacts people. It is a powerful tool we are only just beginning to

understand, and that is a profound responsibility.”

Model assessments

Classification of machine learning models can be validated by accuracy estimation techniques like the holdout

method, which splits the data in a training and test set

(conventionally 2/3 training set and 1/3 test set designation) and

evaluates the performance of the training model on the test set. In

comparison, the K-fold-cross-validation

method randomly partitions the data into K subsets and then K

experiments are performed each respectively considering 1 subset for

evaluation and the remaining K-1 subsets for training the model. In

addition to the holdout and cross-validation methods, bootstrap, which samples n instances with replacement from the dataset, can be used to assess model accuracy.

In addition to overall accuracy, investigators frequently report sensitivity and specificity meaning True Positive Rate (TPR) and True Negative Rate (TNR) respectively. Similarly, investigators sometimes report the false positive rate (FPR) as well as the false negative rate (FNR). However, these rates are ratios that fail to reveal their numerators and denominators. The total operating characteristic

(TOC) is an effective method to express a model's diagnostic ability.

TOC shows the numerators and denominators of the previously mentioned

rates, thus TOC provides more information than the commonly used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and ROC's associated area under the curve (AUC).

Ethics

Machine learning poses a host of ethical questions. Systems which are trained on datasets collected with biases may exhibit these biases upon use (algorithmic bias), thus digitizing cultural prejudices.

For example, in 1988, the UK's Commission for Racial Equality found

that St. George's Medical School had been using a computer program

trained from data of previous admissions staff and this program had

denied nearly 60 candidates who were found to be either women or had

non-European sounding names.

Using job hiring data from a firm with racist hiring policies may lead

to a machine learning system duplicating the bias by scoring job

applicants by similarity to previous successful applicants.

Responsible collection of data and documentation of algorithmic rules used by a system thus is a critical part of machine learning.

AI can be well-equipped to make decisions in technical fields,

which rely heavily on data and historical information. These decisions

rely on objectivity and logical reasoning. Because human languages contain biases, machines trained on language corpora will necessarily also learn these biases.

Other forms of ethical challenges, not related to personal

biases, are seen in health care. There are concerns among health care

professionals that these systems might not be designed in the public's

interest but as income-generating machines.

This is especially true in the United States where there is a

long-standing ethical dilemma of improving health care, but also

increasing profits. For example, the algorithms could be designed to

provide patients with unnecessary tests or medication in which the

algorithm's proprietary owners hold stakes. There is potential for

machine learning in health care to provide professionals an additional

tool to diagnose, medicate, and plan recovery paths for patients, but

this requires these biases to be mitigated.

Hardware

Since

the 2010s, advances in both machine learning algorithms and computer

hardware have led to more efficient methods for training deep neural

networks (a particular narrow subdomain of machine learning) that

contain many layers of non-linear hidden units. By 2019, graphic processing units (GPUs), often with AI-specific enhancements, had displaced CPUs as the dominant method of training large-scale commercial cloud AI. OpenAI

estimated the hardware compute used in the largest deep learning

projects from AlexNet (2012) to AlphaZero (2017), and found a

300,000-fold increase in the amount of compute required, with a

doubling-time trendline of 3.4 months.