| Black Death | |

|---|---|

Spread of the Black Death in Europe and the Near East (1346–1353) | |

| Disease | Bubonic plague |

| Location | Eurasia, North Africa |

| Date | 1346–1353 |

Deaths | 75,000,000–200,000,000 (estimate) |

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Afro-Eurasia from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causing the death of 75–200 million people in Eurasia and North Africa, peaking in Europe from 1347 to 1351. Bubonic plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, but it may also cause septicaemic or pneumonic plagues.

The Black Death was the beginning of the second plague pandemic. The plague created religious, social and economic upheavals, with profound effects on the course of European history.

The origin of the Black Death is disputed. The pandemic originated either in Central Asia or East Asia but its first definitive appearance was in Crimea in 1347. From Crimea, it was most likely carried by fleas living on the black rats that travelled on Genoese slave ships, spreading through the Mediterranean Basin and reaching Africa, Western Asia and the rest of Europe via Constantinople, Sicily and the Italian Peninsula. There is evidence that once it came ashore, the Black Death was in large part spread by fleas – which cause pneumonic plague – and the person-to-person contact via aerosols which pneumonic plague enables, thus explaining the very fast inland spread of the epidemic, which was faster than would be expected if the primary vector was rat fleas causing bubonic plague.

The Black Death was the second great natural disaster to strike Europe during the Late Middle Ages (the first one being the Great Famine of 1315–1317) and is estimated to have killed 30 percent to 60 percent of the European population. The plague might have reduced the world population from c. 475 million to 350–375 million in the 14th century. There were further outbreaks throughout the Late Middle Ages and, with other contributing factors, the European population did not regain its level in 1300 until 1500. Outbreaks of the plague recurred around the world until the early 19th century.

Names

European writers contemporary with the plague described the disease in Latin as pestis or pestilentia, 'pestilence'; epidemia, 'epidemic'; mortalitas, 'mortality'. In English prior to the 18th century, the event was called the "pestilence" or "great pestilence", "the plague" or the "great death". Subsequent to the pandemic "the furste moreyn" (first murrain) or "first pestilence" was applied, to distinguish the mid-14th century phenomenon from other infectious diseases and epidemics of plague. The 1347 pandemic plague was not referred to specifically as "black" in the 14th or 15th centuries in any European language, though the expression "black death" had occasionally been applied to fatal disease beforehand.

"Black death" was not used to describe the plague pandemic in English until the 1750s; the term is first attested in 1755, where it translated Danish: den sorte død, lit. 'the black death'. This expression as a proper name for the pandemic had been popularized by Swedish and Danish chroniclers in the 15th and early 16th centuries, and in the 16th and 17th centuries was transferred to other languages as a calque: Icelandic: svarti dauði, German: der schwarze Tod, and French: la mort noire. Previously, most European languages had named the pandemic a variant or calque of the Latin: magna mortalitas, lit. 'Great Death'.

The phrase 'black death' – describing Death as black – is very old. Homer used it in the Odyssey to describe the monstrous Scylla, with her mouths "full of black Death" (Ancient Greek: πλεῖοι μέλανος Θανάτοιο, romanized: pleîoi mélanos Thanátoio). Seneca the Younger may have been the first to describe an epidemic as 'black death', (Latin: mors atra) but only in reference to the acute lethality and dark prognosis of disease. The 12th–13th century French physician Gilles de Corbeil had already used atra mors to refer to a "pestilential fever" (febris pestilentialis) in his work On the Signs and Symptoms of Diseases (De signis et symptomatibus aegritudium). The phrase mors nigra, 'black death', was used in 1350 by Simon de Covino (or Couvin), a Belgian astronomer, in his poem "On the Judgement of the Sun at a Feast of Saturn" (De judicio Solis in convivio Saturni), which attributes the plague to an astrological conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn. His use of the phrase is not connected unambiguously with the plague pandemic of 1347 and appears to refer to the fatal outcome of disease.

The historian Cardinal Francis Aidan Gasquet wrote about the Great Pestilence in 1893 and suggested that it had been "some form of the ordinary Eastern or bubonic plague". In 1908, Gasquet claimed that use of the name atra mors for the 14th-century epidemic first appeared in a 1631 book on Danish history by J. I. Pontanus: "Commonly and from its effects, they called it the black death" (Vulgo & ab effectu atram mortem vocitabant).

Previous plague epidemics

Recent research has suggested plague first infected humans in Europe and Asia in the Late Neolithic-Early Bronze Age. Research in 2018 found evidence of Yersinia pestis in an ancient Swedish tomb, which may have been associated with the "Neolithic decline" around 3000 BCE, in which European populations fell significantly. This Y. pestis may have been different from more modern types, with bubonic plague transmissible by fleas first known from Bronze Age remains near Samara.

The symptoms of bubonic plague are first attested in a fragment of Rufus of Ephesus preserved by Oribasius; these ancient medical authorities suggest bubonic plague had appeared in the Roman Empire before the reign of Trajan, six centuries before arriving at Pelusium in the reign of Justinian I. In 2013, researchers confirmed earlier speculation that the cause of the Plague of Justinian (541–542 CE, with recurrences until 750) was Y. pestis. This is known as the First plague pandemic.

14th-century plague

Causes

Early theory

The most authoritative contemporary account is found in a report from the medical faculty in Paris to Philip VI of France. It blamed the heavens, in the form of a conjunction of three planets in 1345 that caused a "great pestilence in the air" (miasma theory). Muslim religious scholars taught that the pandemic was a “martyrdom and mercy” from God, assuring the believer's place in paradise. For non-believers, it was a punishment. Some Muslim doctors cautioned against trying to prevent or treat a disease sent by God. Others adopted preventive measures and treatments for plague used by Europeans. These Muslim doctors also depended on the writings of the ancient Greeks.

Predominant modern theory

Due to climate change in Asia, rodents began to flee the dried-out grasslands to more populated areas, spreading the disease. The plague disease, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, is enzootic (commonly present) in populations of fleas carried by ground rodents, including marmots, in various areas, including Central Asia, Kurdistan, Western Asia, North India, Uganda and the western United States.

Y. pestis was discovered by Alexandre Yersin, a pupil of Louis Pasteur, during an epidemic of bubonic plague in Hong Kong in 1894; Yersin also proved this bacillus was present in rodents and suggested the rat was the main vehicle of transmission. The mechanism by which Y. pestis is usually transmitted was established in 1898 by Paul-Louis Simond and was found to involve the bites of fleas whose midguts had become obstructed by replicating Y. pestis several days after feeding on an infected host. This blockage starves the fleas and drives them to aggressive feeding behaviour and attempts to clear the blockage by regurgitation, resulting in thousands of plague bacteria being flushed into the feeding site, infecting the host. The bubonic plague mechanism was also dependent on two populations of rodents: one resistant to the disease, which act as hosts, keeping the disease endemic, and a second that lack resistance. When the second population dies, the fleas move on to other hosts, including people, thus creating a human epidemic.

DNA evidence

Definitive confirmation of the role of Y. pestis arrived in 2010 with a publication in PLOS Pathogens by Haensch et al. They assessed the presence of DNA/RNA with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques for Y. pestis from the tooth sockets in human skeletons from mass graves in northern, central and southern Europe that were associated archaeologically with the Black Death and subsequent resurgences. The authors concluded that this new research, together with prior analyses from the south of France and Germany, "ends the debate about the cause of the Black Death, and unambiguously demonstrates that Y. pestis was the causative agent of the epidemic plague that devastated Europe during the Middle Ages". In 2011, these results were further confirmed with genetic evidence derived from Black Death victims in the East Smithfield burial site in England. Schuenemann et al. concluded in 2011 "that the Black Death in medieval Europe was caused by a variant of Y. pestis that may no longer exist".

Later in 2011, Bos et al. reported in Nature the first draft genome of Y. pestis from plague victims from the same East Smithfield cemetery and indicated that the strain that caused the Black Death is ancestral to most modern strains of Y. pestis.

Since this time, further genomic papers have further confirmed the phylogenetic placement of the Y. pestis strain responsible for the Black Death as both the ancestor of later plague epidemics including the third plague pandemic and as the descendant of the strain responsible for the Plague of Justinian. In addition, plague genomes from significantly earlier in prehistory have been recovered.

DNA taken from 25 skeletons from 14th century London have shown plague is a strain of Y. pestis almost identical to that which hit Madagascar in 2013.

Alternative explanations

It is recognised that an epidemiological account of plague is as important as an identification of symptoms, but researchers are hampered by the lack of reliable statistics from this period. Most work has been done on the spread of the disease in England, and even estimates of overall population at the start vary by over 100% as no census was undertaken in England between the time of publication of the Domesday Book of 1086 and the poll tax of the year 1377. Estimates of plague victims are usually extrapolated from figures for the clergy.

Mathematical modelling is used to match the spreading patterns and the means of transmission. A research in 2018 challenged the popular hypothesis that "infected rats died, their flea parasites could have jumped from the recently dead rat hosts to humans". It suggested an alternative model in which "the disease was spread from human fleas and body lice to other people". The second model claims to better fit the trends of death toll because the rat-flea-human hypothesis would have produced a delayed but very high spike in deaths, which contradict historical death data.

Lars Walløe complains that all of these authors "take it for granted that Simond's infection model, black rat → rat flea → human, which was developed to explain the spread of plague in India, is the only way an epidemic of Yersinia pestis infection could spread", whilst pointing to several other possibilities. Similarly, Monica Green has argued that greater attention is needed to the range of (especially non-commensal) animals that might be involved in the transmission of plague.

Archaeologist Barney Sloane has argued that there is insufficient evidence of the extinction of numerous rats in the archaeological record of the medieval waterfront in London and that the disease spread too quickly to support the thesis that Y. pestis was spread from fleas on rats; he argues that transmission must have been person to person. This theory is supported by research in 2018 which suggested transmission was more likely by body lice and fleas during the second plague pandemic.

Summary

Although academic debate continues, no single alternative solution has achieved widespread acceptance. Many scholars arguing for Y. pestis as the major agent of the pandemic suggest that its extent and symptoms can be explained by a combination of bubonic plague with other diseases, including typhus, smallpox and respiratory infections. In addition to the bubonic infection, others point to additional septicaemic (a type of "blood poisoning") and pneumonic (an airborne plague that attacks the lungs before the rest of the body) forms of plague, which lengthen the duration of outbreaks throughout the seasons and help account for its high mortality rate and additional recorded symptoms. In 2014, Public Health England announced the results of an examination of 25 bodies exhumed in the Clerkenwell area of London, as well as of wills registered in London during the period, which supported the pneumonic hypothesis. Currently, while osteoarcheologists have conclusively verified the presence of Y. pestis bacteria in burial sites across northern Europe through examination of bones and dental pulp, no other epidemic pathogen has been discovered to bolster the alternative explanations. In the words of one researcher: "Finally, plague is plague."

Transmission

The importance of hygiene was recognised only in the nineteenth century with the development of the germ theory of disease; until then streets were commonly filthy, with live animals of all sorts around and human parasites abounding, facilitating the spread of transmissible disease.

Territorial origins

According to a team of medical geneticists led by Mark Achtman that analysed the genetic variation of the bacterium, Yersinia pestis "evolved in or near China", from which it spread around the world in multiple epidemics. Later research by a team led by Galina Eroshenko places the origins more specifically in the Tian Shan mountains on the border between Kyrgyzstan and China.

Nestorian graves dating to 1338–1339 near Issyk-Kul in Kyrgyzstan have inscriptions referring to plague, which has led some historians and epidemiologists to think they mark the outbreak of the epidemic. Others favour an origin in China. According to this theory, the disease may have travelled along the Silk Road with Mongol armies and traders, or it could have arrived via ship. Epidemics killed an estimated 25 million across Asia during the fifteen years before the Black Death reached Constantinople in 1347.

Research on the Delhi Sultanate and the Yuan Dynasty shows no evidence of any serious epidemic in fourteenth-century India and no specific evidence of plague in fourteenth-century China, suggesting that the Black Death may not have reached these regions. Ole Benedictow argues that since the first clear reports of the Black Death come from Kaffa, the Black Death most likely originated in the nearby plague focus on the northwestern shore of the Caspian Sea.

European outbreak

... But at length it came to Gloucester, yea even to Oxford and to London, and finally it spread over all England and so wasted the people that scarce the tenth person of any sort was left alive.

Geoffrey the Baker, Chronicon Angliae

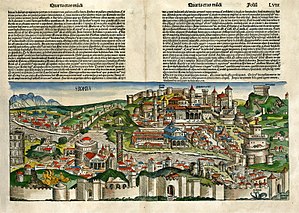

Plague was reportedly first introduced to Europe via Genoese traders from their port city of Kaffa in the Crimea in 1347. During a protracted siege of the city, in 1345–1346 the Mongol Golden Horde army of Jani Beg, whose mainly Tatar troops were suffering from the disease, catapulted infected corpses over the city walls of Kaffa to infect the inhabitants, though it is more likely that infected rats travelled across the siege lines to spread the epidemic to the inhabitants. As the disease took hold, Genoese traders fled across the Black Sea to Constantinople, where the disease first arrived in Europe in summer 1347.

The epidemic there killed the 13-year-old son of the Byzantine emperor, John VI Kantakouzenos, who wrote a description of the disease modelled on Thucydides's account of the 5th century BCE Plague of Athens, but noting the spread of the Black Death by ship between maritime cities. Nicephorus Gregoras also described in writing to Demetrios Kydones the rising death toll, the futility of medicine, and the panic of the citizens. The first outbreak in Constantinople lasted a year, but the disease recurred ten times before 1400.

Carried by twelve Genoese galleys, plague arrived by ship in Sicily in October 1347; the disease spread rapidly all over the island. Galleys from Kaffa reached Genoa and Venice in January 1348, but it was the outbreak in Pisa a few weeks later that was the entry point to northern Italy. Towards the end of January, one of the galleys expelled from Italy arrived in Marseilles.

From Italy, the disease spread northwest across Europe, striking France, Spain (the epidemic began to wreak havoc first on the Crown of Aragon in the spring of 1348), Portugal and England by June 1348, then spread east and north through Germany, Scotland and Scandinavia from 1348 to 1350. It was introduced into Norway in 1349 when a ship landed at Askøy, then spread to Bjørgvin (modern Bergen) and Iceland. Finally, it spread to northwestern Russia in 1351. Plague was somewhat more uncommon in parts of Europe with less developed trade with their neighbours, including the majority of the Basque Country, isolated parts of Belgium and the Netherlands, and isolated Alpine villages throughout the continent.

According to some epidemiologists, periods of unfavourable weather decimated plague-infected rodent populations and forced their fleas onto alternative hosts, inducing plague outbreaks which often peaked in the hot summers of the Mediterranean, as well as during the cool autumn months of the southern Baltic states. Among many other culprits of plague contagiousness, malnutrition, even if distantly, also contributed to such an immense loss in European population, since it weakened immune systems.

Western Asian and North African outbreak

The disease struck various regions in the Middle East and North Africa during the pandemic, leading to serious depopulation and permanent change in both economic and social structures. As infected rodents infected new rodents, the disease spread across the region, entering also from southern Russia.

By autumn 1347, plague had reached Alexandria in Egypt, transmitted by sea from Constantinople; according to a contemporary witness, from a single merchant ship carrying slaves. By late summer 1348 it reached Cairo, capital of the Mamluk Sultanate, cultural centre of the Islamic world, and the largest city in the Mediterranean Basin; the Bahriyya child sultan an-Nasir Hasan fled and more than a third of the 600,000 residents died. The Nile was choked with corpses despite Cairo having a medieval hospital, the late 13th century bimaristan of the Qalawun complex. The historian al-Maqrizi described the abundant work for grave-diggers and practitioners of funeral rites, and plague recurred in Cairo more than fifty times over the following century and half.

During 1347, the disease travelled eastward to Gaza by April; by July it had reached Damascus, and in October plague had broken out in Aleppo. That year, in the territory of modern Lebanon, Syria, Israel, and Palestine, the cities of Ashkelon, Acre, Jerusalem, Sidon, and Homs were all infected. In 1348–1349, the disease reached Antioch. The city's residents fled to the north, but most of them ended up dying during the journey. Within two years, the plague had spread throughout the Islamic world, from Arabia across North Africa. The pandemic spread westwards from Alexandria along the African coast, while in April 1348 Tunis was infected by ship from Sicily. Tunis was then under attack by an army from Morocco; this army dispersed in 1348 and brought the contagion with them to Morocco, whose epidemic may also have been seeded from the Islamic city of Almería in al-Andalus.

Mecca became infected in 1348 by pilgrims performing the Hajj. In 1351 or 1352, the Rasulid sultan of the Yemen, al-Mujahid Ali, was released from Mamluk captivity in Egypt and carried plague with him on his return home. During 1348, records show the city of Mosul suffered a massive epidemic, and the city of Baghdad experienced a second round of the disease.

Signs and symptoms

Bubonic plague

Symptoms of the disease include fever of 38–41 °C (100–106 °F), headaches, painful aching joints, nausea and vomiting, and a general feeling of malaise. Left untreated, of those that contract the bubonic plague, 80 percent die within eight days.

Contemporary accounts of the pandemic are varied and often imprecise. The most commonly noted symptom was the appearance of buboes (or gavocciolos) in the groin, neck, and armpits, which oozed pus and bled when opened. Boccaccio's description:

In men and women alike it first betrayed itself by the emergence of certain tumours in the groin or armpits, some of which grew as large as a common apple, others as an egg ... From the two said parts of the body this deadly gavocciolo soon began to propagate and spread itself in all directions indifferently; after which the form of the malady began to change, black spots or livid making their appearance in many cases on the arm or the thigh or elsewhere, now few and large, now minute and numerous. As the gavocciolo had been and still was an infallible token of approaching death, such also were these spots on whomsoever they showed themselves.

This was followed by acute fever and vomiting of blood. Most victims died two to seven days after initial infection. Freckle-like spots and rashes, which could have been caused by flea-bites, were identified as another potential sign of plague.

Pneumonic plague

Lodewijk Heyligen, whose master the Cardinal Colonna died of plague in 1348, noted a distinct form of the disease, pneumonic plague, that infected the lungs and led to respiratory problems. Symptoms include fever, cough, and blood-tinged sputum. As the disease progresses, sputum becomes free-flowing and bright red. Pneumonic plague has a mortality rate of 90 to 95 percent.

Septicaemic plague

Septicaemic plague is the least common of the three forms, with a mortality rate near 100%. Symptoms are high fevers and purple skin patches (purpura due to disseminated intravascular coagulation). In cases of pneumonic and particularly septicaemic plague, the progress of the disease is so rapid that there would often be no time for the development of the enlarged lymph nodes that were noted as buboes.

Consequences

Deaths

There are no exact figures for the death toll; the rate varied widely by locality. In urban centres, the greater the population before the outbreak, the longer the duration of the period of abnormal mortality. It killed some 75 to 200 million people in Eurasia. The mortality rate of the Black Death in the 14th century was far greater than the worst 20th-century outbreaks of Y. pestis plague, which occurred in India and killed as much as 3% of the population of certain cities. The overwhelming number of deceased bodies produced by the Black Death caused the necessity of mass burial sites in Europe, sometimes including up to several hundred or several thousand skeletons. The mass burial sites that have been excavated have allowed archaeologists to continue interpreting and defining the biological, sociological, historical, and anthropological implications of the Black Death.

According to medieval historian Philip Daileader, it is likely that over four years, 45–50% of the European population died of plague. Norwegian historian Ole Benedictow suggests it could have been as much as 60% of the European population. In 1348, the disease spread so rapidly that before any physicians or government authorities had time to reflect upon its origins, about a third of the European population had already perished. In crowded cities, it was not uncommon for as much as 50% of the population to die. Half of Paris' population of 100,000 people died. In Italy, the population of Florence was reduced from between 110,000 and 120,000 inhabitants in 1338 down to 50,000 in 1351. At least 60% of the population of Hamburg and Bremen perished, and a similar percentage of Londoners may have died from the disease as well, with a death toll of approximately 62,000 between 1346 and 1353. Florence's tax records suggest that 80% of the city's population died within four months in 1348. Before 1350, there were about 170,000 settlements in Germany, and this was reduced by nearly 40,000 by 1450. The disease bypassed some areas, with the most isolated areas being less vulnerable to contagion. Plague did not appear in Douai in Flanders until the turn of the 15th century, and the impact was less severe on the populations of Hainaut, Finland, northern Germany, and areas of Poland. Monks, nuns, and priests were especially hard-hit since they cared for victims of the Black Death.

The physician to the Avignon Papacy, Raimundo Chalmel de Vinario (Latin: Magister Raimundus, lit. 'Master Raymond'), observed the decreasing mortality rate of successive outbreaks of plague in 1347–48, 1362, 1371, and 1382 in his 1382 treatise On Epidemics (De epidemica). In the first outbreak, two thirds of the population contracted the illness and most patients died; in the next, half the population became ill but only some died; by the third, a tenth were affected and many survived; while by the fourth occurrence, only one in twenty people were sickened and most of them survived. By the 1380s in Europe, it predominantly affected children. Chalmel de Vinario recognized that bloodletting was ineffective (though he continued to prescribe bleeding for members of the Roman Curia, whom he disliked), and claimed that all true cases of plague were caused by astrological factors and were incurable; he himself was never able to effect a cure.

The most widely accepted estimate for the Middle East, including Iraq, Iran, and Syria, during this time, is for a death toll of about a third of the population. The Black Death killed about 40% of Egypt's population. In Cairo, with a population numbering as many as 600,000, and possibly the largest city west of China, between one third and 40% of the inhabitants died inside of eight months.

Italian chronicler Agnolo di Tura recorded his experience from Siena, where plague arrived in May 1348:

Father abandoned child, wife husband, one brother another; for this illness seemed to strike through the breath and sight. And so they died. And none could be found to bury the dead for money or friendship. Members of a household brought their dead to a ditch as best they could, without priest, without divine offices ... great pits were dug and piled deep with the multitude of dead. And they died by the hundreds both day and night ... And as soon as those ditches were filled more were dug ... And I, Agnolo di Tura ... buried my five children with my own hands. And there were also those who were so sparsely covered with earth that the dogs dragged them forth and devoured many bodies throughout the city. There was no one who wept for any death, for all awaited death. And so many died that all believed it was the end of the world.

Economic

With such a large population decline from the pandemic, wages soared in response to a labour shortage. On the other hand, in the quarter century after the Black Death in England, it is clear many labourers, artisans, and craftsmen, those living from money-wages alone, did suffer a reduction in real incomes owing to rampant inflation. Landowners were also pushed to substitute monetary rents for labour services in an effort to keep tenants.

Environmental

Some historians believe the innumerable deaths brought on by the pandemic cooled the climate by freeing up land and triggering reforestation. This may have led to the Little Ice Age.

Persecutions

Renewed religious fervour and fanaticism bloomed in the wake of the Black Death. Some Europeans targeted "various groups such as Jews, friars, foreigners, beggars, pilgrims", lepers, and Romani, blaming them for the crisis. Lepers, and others with skin diseases such as acne or psoriasis, were killed throughout Europe.

Because 14th-century healers and governments were at a loss to explain or stop the disease, Europeans turned to astrological forces, earthquakes, and the poisoning of wells by Jews as possible reasons for outbreaks. Many believed the epidemic was a punishment by God for their sins, and could be relieved by winning God's forgiveness.

There were many attacks against Jewish communities. In the Strasbourg massacre of February 1349, about 2,000 Jews were murdered. In August 1349, the Jewish communities in Mainz and Cologne were annihilated. By 1351, 60 major and 150 smaller Jewish communities had been destroyed. During this period many Jews relocated to Poland, where they received a warm welcome from King Casimir the Great.

Social

One theory that has been advanced is that the devastation in Florence caused by the Black Death, which hit Europe between 1348 and 1350, resulted in a shift in the world view of people in 14th-century Italy and led to the Renaissance. Italy was particularly badly hit by the pandemic, and it has been speculated that the resulting familiarity with death caused thinkers to dwell more on their lives on Earth, rather than on spirituality and the afterlife. It has also been argued that the Black Death prompted a new wave of piety, manifested in the sponsorship of religious works of art.

This does not fully explain why the Renaissance occurred in Italy in the 14th century. The Black Death was a pandemic that affected all of Europe in the ways described, not only Italy. The Renaissance's emergence in Italy was most likely the result of the complex interaction of the above factors, in combination with an influx of Greek scholars following the fall of the Byzantine Empire. As a result of the drastic reduction in the populace the value of the working class increased, and commoners came to enjoy more freedom. To answer the increased need for labour, workers travelled in search of the most favorable position economically.

Prior to the emergence of the Black Death, the workings of Europe were run by the Catholic Church and the continent was considered a feudalistic society, composed of fiefs and city-states. The pandemic completely restructured both religion and political forces; survivors began to turn to other forms of spirituality and the power dynamics of the fiefs and city-states crumbled.

Cairo's population, partly owing to the numerous plague epidemics, was in the early 18th century half of what it was in 1347. The populations of some Italian cities, notably Florence, did not regain their pre-14th century size until the 19th century. The demographic decline due to the pandemic had economic consequences: the prices of food dropped and land values declined by 30–40% in most parts of Europe between 1350 and 1400. Landholders faced a great loss, but for ordinary men and women it was a windfall. The survivors of the pandemic found not only that the prices of food were lower but also that lands were more abundant, and many of them inherited property from their dead relatives, and this probably destabilized feudalism.

The word "quarantine" has its roots in this period, though the concept of isolating people to prevent the spread of disease is older. In the city-state of Ragusa (modern Dubrovnik, Croatia), a thirty-day isolation period was implemented in 1377 for new arrivals to the city from plague-affected areas. The isolation period was later extended to forty days, and given the name "quarantino" from the Italian word for "forty".

Recurrences

Second plague pandemic

The plague repeatedly returned to haunt Europe and the Mediterranean throughout the 14th to 17th centuries. According to Jean-Noël Biraben, the plague was present somewhere in Europe in every year between 1346 and 1671. (Note that some researchers have cautions about the uncritical use of Biraben's data.) The second pandemic was particularly widespread in the following years: 1360–63; 1374; 1400; 1438–39; 1456–57; 1464–66; 1481–85; 1500–03; 1518–31; 1544–48; 1563–66; 1573–88; 1596–99; 1602–11; 1623–40; 1644–54; and 1664–67. Subsequent outbreaks, though severe, marked the retreat from most of Europe (18th century) and northern Africa (19th century). The historian George Sussman argued that the plague had not occurred in East Africa until the 1900s. However, other sources suggest that the Second pandemic did indeed reach Sub-Saharan Africa.

According to historian Geoffrey Parker, "France alone lost almost a million people to the plague in the epidemic of 1628–31." In the first half of the 17th century, a plague claimed some 1.7 million victims in Italy. More than 1.25 million deaths resulted from the extreme incidence of plague in 17th-century Spain.

The Black Death ravaged much of the Islamic world. Plague was present in at least one location in the Islamic world virtually every year between 1500 and 1850. Plague repeatedly struck the cities of North Africa. Algiers lost 30,000–50,000 inhabitants to it in 1620–21, and again in 1654–57, 1665, 1691, and 1740–42. Cairo suffered more than fifty plague epidemics within 150 years from the plague's first appearance, with the final outbreak of the second pandemic there in the 1840s. Plague remained a major event in Ottoman society until the second quarter of the 19th century. Between 1701 and 1750, thirty-seven larger and smaller epidemics were recorded in Constantinople, and an additional thirty-one between 1751 and 1800. Baghdad has suffered severely from visitations of the plague, and sometimes two-thirds of its population has been wiped out.

Third plague pandemic

The third plague pandemic (1855–1859) started in China in the mid-19th century, spreading to all inhabited continents and killing 10 million people in India alone. The investigation of the pathogen that caused the 19th-century plague was begun by teams of scientists who visited Hong Kong in 1894, among whom was the French-Swiss bacteriologist Alexandre Yersin, after whom the pathogen was named.

Twelve plague outbreaks in Australia between 1900 and 1925 resulted in well over 1,000 deaths, chiefly in Sydney. This led to the establishment of a Public Health Department there which undertook some leading-edge research on plague transmission from rat fleas to humans via the bacillus Yersinia pestis.

The first North American plague epidemic was the San Francisco plague of 1900–1904, followed by another outbreak in 1907–1908.

Modern-day

Modern treatment methods include insecticides, the use of antibiotics, and a plague vaccine. It is feared that the plague bacterium could develop drug resistance and again become a major health threat. One case of a drug-resistant form of the bacterium was found in Madagascar in 1995. A further outbreak in Madagascar was reported in November 2014. In October 2017 the deadliest outbreak of the plague in modern times hit Madagascar, killing 170 people and infecting thousands.

An estimate of the case fatality rate for the modern bubonic plague, following the introduction of antibiotics, is 11%, although it may be higher in underdeveloped regions.