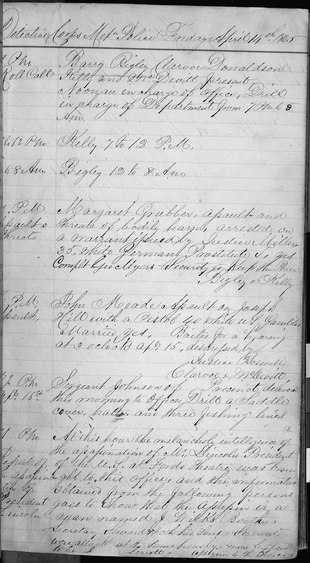

| Assassination of Abraham Lincoln | |

|---|---|

| Location | Ford's Theatre, Washington, D.C. |

| Date | April 14, 1865 10:15 p.m. |

| Target |

|

Attack type |

|

| Weapons |

|

| Deaths | Abraham Lincoln (died April 15, 1865, at 7:22 a.m. from his injuries) |

| Injured | John Wilkes Booth (the perpetrator)

|

| Perpetrators | John Wilkes Booth and co-conspirators |

| Motive | Revenge for the Confederate States |

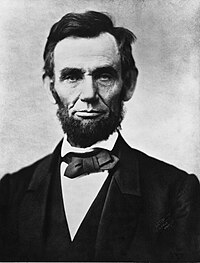

Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States, was assassinated by well-known stage actor John Wilkes Booth on April 14, 1865, while attending the play Our American Cousin at Ford's Theater in Washington, D.C. Shot in the head as he watched the play, Lincoln died the following day at 7:22 am, in the Petersen House opposite the theater. He was the first U.S. president to be assassinated, with his funeral and burial marking an extended period of national mourning.

Occurring near the end of the American Civil War, the assassination was part of a larger conspiracy intended by Booth to revive the Confederate cause by eliminating the three most important officials of the United States government. Conspirators Lewis Powell and David Herold were assigned to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward, and George Atzerodt was tasked with killing Vice President Andrew Johnson. Beyond Lincoln's death, the plot failed: Seward was only wounded, and Johnson's would-be attacker lost his nerve. After a dramatic initial escape, Booth was killed at the climax of a 12-day chase. Powell, Herold, Atzerodt, and Mary Surratt were later hanged for their roles in the conspiracy.

Background

Abandoned plan to kidnap Lincoln

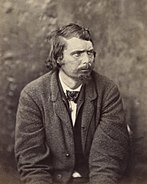

John Wilkes Booth, born in Maryland into a family of prominent stage actors, had by the time of the assassination become a famous actor and national celebrity in his own right. He was also an outspoken Confederate sympathizer; in late 1860 he was initiated in the pro-Confederate Knights of the Golden Circle in Baltimore.

In March 1864, Ulysses S. Grant, commander of the Union armies, suspended the exchange of prisoners of war with the Confederate Army to increase pressure on the manpower-starved South. Booth conceived a plan to kidnap Lincoln in order to blackmail the North into resuming prisoner exchanges, and recruited Samuel Arnold, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Michael O'Laughlen, Lewis Powell (also known as "Lewis Paine"), and John Surratt to help him. Surratt's mother, Mary Surratt, left her tavern in Surrattsville, Maryland, and moved to a house in Washington, D.C., where Booth became a frequent visitor.

While Booth and Lincoln were not personally acquainted, Lincoln had seen Booth at Ford's in 1863.2`sz After the assassination, actor Frank Mordaunt wrote that Lincoln, who apparently harbored no suspicions about Booth, admired the actor and had repeatedly invited him (without success) to visit the White House. Booth attended Lincoln's second inauguration on March 4, 1865, writing in his diary afterwards: "What an excellent chance I had, if I wished, to kill the President on Inauguration day!"

On March 17, Booth and the other conspirators planned to abduct Lincoln as he returned from a play at Campbell Military Hospital. But Lincoln did not go to the play, instead attending a ceremony at the National Hotel; Booth was living at the National Hotel at the time and, had he not gone to the hospital for the abortive kidnap attempt, might have been able to attack Lincoln at the hotel.

Meanwhile, the Confederacy was collapsing. On April 3, Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital, fell to the Union Army. On April 9, the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate States Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia surrendered to the Commanding General of the United States Army Ulysses S. Grant and his Army of the Potomac after the Battle of Appomattox Court House. Confederate President Jefferson Davis and other Confederate officials had fled. Nevertheless, Booth continued to believe in the Confederate cause and sought a way to salvage it.

Motive

There are various theories about Booth's motivations. In a letter to his mother, he wrote of his desire to avenge the South. Doris Kearns Goodwin has endorsed the idea that another factor was Booth's rivalry with his well-known older brother, actor Edwin Booth, who was a loyal Unionist. David S. Reynolds believes Booth greatly admired the abolitionist John Brown; Booth's sister Asia Booth Clarke quoted him as saying: "John Brown was a man inspired, the grandest character of the century!" On April 11, Booth attended Lincoln's last speech, in which Lincoln promoted voting rights for blacks; Booth said "That means nigger citizenship. ...That is the last speech he will ever give."

Enraged, Booth urged Lewis Powell to shoot Lincoln on the spot. Whether Booth made this request because he was not armed or considered Powell a better shot than himself (Powell, unlike Booth, had served in the Confederate Army and thus had military experience) is unknown. In any event, Powell refused for fear of the crowd, and Booth was either unable or unwilling to personally attempt to kill the president. However, Booth said to David Herold, "By God, I'll put him through."

Lincoln's premonitions

According to Ward Hill Lamon, three days before his death, Lincoln related a dream in which he wandered the White House searching for the source of mournful sounds:

I kept on until I arrived at the East Room, which I entered. There I met with a sickening surprise. Before me was a catafalque, on which rested a corpse wrapped in funeral vestments. Around it were stationed soldiers who were acting as guards; and there was a throng of people, gazing mournfully upon the corpse, whose face was covered, others weeping pitifully. "Who is dead in the White House?" I demanded of one of the soldiers, "The President," was his answer; "he was killed by an assassin."

However, Lincoln went on to tell Lamon that "In this dream it was not me, but some other fellow, that was killed. It seems that this ghostly assassin tried his hand on someone else." Paranormal investigator Joe Nickell writes that dreams of assassination would not be unexpected in the first place, considering the Baltimore Plot and an additional assassination attempt in which a hole was shot through Lincoln's hat.

For months Lincoln had looked pale and haggard, but on the morning of the assassination, he told people how happy he was. First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln felt such talk could bring bad luck. Lincoln told his cabinet that he had dreamed of being on a "singular and indescribable vessel that was moving with great rapidity toward a dark and indefinite shore", and that he had had the same dream before "nearly every great and important event of the War" such as the victories at Antietam, Murfreesboro, Gettysburg and Vicksburg.

Preparations

On April 14, Booth's morning started at midnight. He wrote his mother that all was well but that he was "in haste". In his diary, he wrote that "Our cause being almost lost, something decisive and great must be done".

While visiting Ford's Theatre around noon to pick up his mail, Booth learned that Lincoln and Grant were to see Our American Cousin there that night. This provided him with an especially good opportunity to attack Lincoln since, having performed there several times, he knew the theater's layout and was familiar to its staff. He went to Mary Surratt's boarding house in Washington, D.C., and asked her to deliver a package to her tavern in Surrattsville, Maryland. He also asked her to tell her tenant Louis J. Weichmann to ready the guns and ammunition that Booth had previously stored at the tavern.

The conspirators met for the final time at 8:45 p.m. Booth assigned Lewis Powell to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward at his home, George Atzerodt to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson at the Kirkwood Hotel, and David E. Herold to guide Powell (who was unfamiliar with Washington) to the Seward house and then to a rendezvous with Booth in Maryland.

John Wilkes Booth was the only well-known member of the conspiracy. It is likely he reasonably (but ultimately, incorrectly) assumed that the entrance of the Presidential Box would be guarded and that he would be the only plotter with a plausible chance of gaining access to the President, or at least to gain entry to the box without being searched for weapons first. Booth planned to shoot Lincoln at point-blank range with his single-shot Deringer and then stab Grant at Ford's Theatre. They were all to strike simultaneously shortly after ten o'clock. Atzerodt tried to withdraw from the plot, which to this point had involved only kidnapping, not murder, but Booth pressured him to continue.

Assassination of Lincoln

Lincoln arrives at the theater

Despite what Booth had heard earlier in the day, Grant and his wife, Julia Grant, had declined to accompany the Lincolns, as Mary Lincoln and Julia Grant were not on good terms. Others in succession also declined the Lincolns' invitation, until finally Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée Clara Harris (daughter of New York Senator Ira Harris) accepted. At one point Mary Lincoln developed a headache and was inclined to stay home, but Lincoln told her he must attend because newspapers had announced that he would. Lincoln's footman, William H. Crook, advised him not to go, but Lincoln said he had promised his wife. Lincoln told Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax, "I suppose it's time to go though I would rather stay" before assisting Mary into the carriage.

The presidential party arrived late and settled into their box (two adjoining boxes with a dividing partition removed). The play was interrupted, and the orchestra played "Hail to the Chief" as the full house of some 1,700 rose in applause. Lincoln sat in a rocking chair that had been selected for him from among the Ford family's personal furnishings.

The cast modified a line of the play in honor of Lincoln: when the heroine asked for a seat protected from the draft, the reply – scripted as, "Well, you're not the only one that wants to escape the draft" – was delivered instead as "The draft has already been stopped by order of the President!" A member of the audience observed that Mary Lincoln often called her husband's attention to aspects of the action onstage, and "seemed to take great pleasure in witnessing his enjoyment."

At one point, Mary Lincoln whispered to Lincoln, who was holding her hand, "What will Miss Harris think of my hanging on to you so?" Lincoln replied, "She won't think anything about it". In following years, these words were traditionally considered Lincoln's last, though N.W. Miner, a family friend, claimed in 1882 that Mary Lincoln told him that Lincoln's last words expressed a wish to visit Jerusalem.

Booth shoots Lincoln

With Crook off duty and Ward Hill Lamon away, policeman John Frederick Parker was assigned to guard the president's box. At intermission he went to a nearby tavern along with Lincoln's valet, Charles Forbes, and Coachman Francis Burke. It was also the same tavern Booth was waiting by having several drinks to prepare his time. It is unclear whether he returned to the theater, but he was certainly not at his post when Booth entered the box. In any event, there is no certainty that entry would have been denied to a celebrity such as Booth. Booth had prepared a brace to bar the door after entering the box, indicating that he expected a guard. After spending time at the saloon, Booth entered Ford's Theater one last time at about 10:10 pm, this time, through the theater's front entrance. He passed through the dress circle and went to the door that led to the Presidential Box after showing Charles Forbes his calling card. Navy Surgeon George Brainerd Todd saw Booth arrive:

About 10:25 pm, a man came in and walked slowly along the side on which the "Pres" box was and I heard a man say, "There's Booth" and I turned my head to look at him. He was still walking very slow and was near the box door when he stopped, took a card from his pocket, wrote something on it, and gave it to the usher who took it to the box. In a minute the door was opened and he walked in.

Once inside the hallway, Booth barricaded the door by wedging a stick between it and the wall. From here, a second door led to Lincoln's box. There is evidence that, earlier in the day, Booth had bored a peephole in this second door, though this is not certain.

Booth knew the play by heart and waited to time his shot at about 10:15 pm, with the laughter at one of the hilarious lines of the play, delivered by actor Harry Hawk: "Well, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old gal; you sockdologizing old man-trap!". Lincoln was laughing at this line when Booth opened the door, stepped forward, and shot Lincoln from behind with a derringer.

The bullet entered Lincoln's skull behind his left ear, passed through his brain, and came to rest near the front of the skull after fracturing both orbital plates. Lincoln slumped over in his chair and then fell backward. Rathbone turned to see Booth standing in gunsmoke less than four feet behind Lincoln; Booth shouted a word that Rathbone thought sounded like "Freedom!"

Booth escapes

Rathbone jumped from his seat and struggled with Booth, who dropped the pistol and drew a knife, with which he stabbed Rathbone in the left forearm. Rathbone again grabbed at Booth as Booth prepared to jump from the box to the stage, a twelve-foot drop; Booth's riding spur became entangled on the Treasury flag decorating the box, and he landed awkwardly on his left foot. As he began crossing the stage, many in the audience thought he was part of the play.

Booth held his bloody knife over his head and yelled something to the audience. While it is traditionally held that Booth shouted the Virginia state motto, Sic semper tyrannis! ("Thus always to tyrants") either from the box or the stage, witness accounts conflict. Most recalled hearing Sic semper tyrannis! but others – including Booth himself – said he yelled only Sic semper! (Some did not recall Booth saying anything in Latin.) There is similar uncertainty about what Booth shouted next, in English: either "The South is avenged!", "Revenge for the South!", or "The South shall be free!" (Two witnesses remembered Booth's words as: "I have done it!")

Immediately after Booth landed on the stage, Major Joseph B. Stewart climbed over the orchestra pit and footlights and pursued Booth across the stage. The screams of Mary Lincoln and Clara Harris, and Rathbone's cries of "Stop that man!" prompted others to join the chase as pandemonium broke out.

Booth ran across the stage and exited through a side door, en route stabbing orchestra leader William Withers, Jr. He had left a horse in the alleyway. As he leapt into the saddle Booth pushed away Joseph Burroughs, who had been holding the horse, striking Burroughs with the handle of his knife.

Death of Lincoln

Charles Leale, a young Army surgeon, pushed through the crowd to the door of Lincoln's box, but could not open it until Rathbone, inside, noticed and removed the wooden brace with which Booth had jammed the door shut.

Leale found Lincoln seated with his head leaning to his right as Mary held him and sobbed: "His eyes were closed and he was in a profoundly comatose condition, while his breathing was intermittent and exceedingly stertorous." Thinking Lincoln had been stabbed, Leale shifted him to the floor. Meanwhile, another physician, Charles Sabin Taft, was lifted into the box from the stage.

After bystander William Kent and Leale cut away Lincoln's collar while unbuttoning Lincoln's coat and shirt and found no stab wound, Leale located the gunshot wound behind the left ear. He found the bullet too deep to be removed but dislodged a clot, after which Lincoln's breathing improved; he learned that regularly removing new clots maintained Lincoln's breathing. After giving Lincoln artificial respiration, Dr. Leale allowed actress Laura Keene to cradle the President's head in her lap, and he pronounced the wound mortal.

Leale, Taft, and another doctor, Albert King, decided that Lincoln must be moved to the nearest house on Tenth Street because a carriage ride to the White House was too dangerous. Carefully, seven men picked up Lincoln and slowly carried him out of the theater, where it was packed with an angry mob. After considering Peter Taltavull's Star Saloon next door, they concluded that they would take Lincoln to one of the houses across the way. It was raining as soldiers carried Lincoln into the street, where a man urged them toward the house of tailor William Petersen. In Petersen's first-floor bedroom, the exceptionally tall Lincoln was laid diagonally on a small bed.

After clearing everyone out of the room, including Mrs. Lincoln, the doctors cut away Lincoln's clothes but discovered no other wounds; finding that Lincoln was cold, they applied hot water bottles and mustard plasters while covering his cold body with blankets. Later, more physicians arrived: Surgeon General Joseph K. Barnes, Charles Henry Crane, Anderson Ruffin Abbott, and Robert K. Stone (Lincoln's personal physician). All agreed Lincoln could not survive. Barnes probed the wound, locating the bullet and some bone fragments. Throughout the night, as the hemorrhage continued, they removed blood clots to relieve pressure on the brain, and Leale held the comatose president's hand with a firm grip, "to let him know that he was in touch with humanity and had a friend."

Lincoln's older son Robert Todd Lincoln arrived at about 11 p.m., but twelve-year-old Tad Lincoln, who was watching a play of “Aladdin” at Grover's Theater when he learned of his father's assassination at Ford's Theater, was kept away. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton arrived. Stanton insisted that the sobbing Mary Lincoln leave the sick room, then for the rest of the night, he essentially ran the United States government from the house, including directing the hunt for Booth and the other conspirators. Guards kept the public away, but numerous officials and physicians were admitted to pay their respects.

Initially, Lincoln's features were calm and his breathing slow and steady. Later, one of his eyes became swollen, and the right side of his face discolored. Maunsell Bradhurst Field wrote in a letter to The New York Times that the President then started "breathing regularly, but with effort, and did not seem to be struggling or suffering." As he neared death, Lincoln's appearance became "perfectly natural" (except for the discoloration around his eyes). Shortly before 7 a.m. Mary was allowed to return to Lincoln's side, and, as Dixon reported, "she again seated herself by the President, kissing him and calling him every endearing name."

Lincoln died at 7:22 a.m. on April 15. Mary Lincoln was not present. In his last moments, Lincoln's face became calm and his breathing quieter. Field wrote there was "no apparent suffering, no convulsive action, no rattling of the throat ... [only] a mere cessation of breathing". According to Lincoln's secretary John Hay, at the moment of Lincoln's death, "a look of unspeakable peace came upon his worn features". The assembly knelt for a prayer, after which Stanton said either "Now he belongs to the ages" or "Now he belongs to the angels."

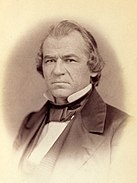

On Lincoln's death, Vice President Johnson became the 17th president, and was sworn in by Chief Justice Salmon Chase between 10 and 11 a.m.

Powell attacks Seward

Booth had assigned Lewis Powell to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward. On the night of the assassination, Seward was at his home in Lafayette Park, confined to bed and recovering from injuries sustained April 5 from being thrown from his carriage. Herold guided Powell to Seward's house. Powell carried an 1858 Whitney revolver (a large, heavy, and popular gun during the Civil War) and a Bowie knife.

William Bell, Seward's maître d’, answered the door when Powell knocked 10:10 pm, as Booth made his way to the presidential box at Ford's Theater. Powell told Bell that he had medicine from Seward's physician and that his instructions were to personally show Seward how to take it. Overcoming Bell's skepticism, Powell made his way up the stairs to Seward's third-floor bedroom. At the top of the staircase he was stopped by Seward's son, Assistant Secretary of State Frederick W. Seward, to whom he repeated the medicine story; Frederick, suspicious, said his father was asleep.

Hearing voices, Seward's daughter Fanny emerged from Seward's room and said, "Fred, Father is awake now" – thus revealing to Powell where Seward was. Powell turned as if to start downstairs but suddenly turned again and drew his revolver. He aimed at Frederick's forehead and pulled the trigger, but the gun misfired, so he bludgeoned Frederick unconscious with it. Bell, yelling "Murder! Murder!", ran outside for help.

Fanny opened the door again, and Powell shoved past her to Seward's bed. He stabbed at Seward's face and neck, slicing open his cheek. However, the splint (often mistakenly described as a neck brace) that doctors had fitted to Seward's broken jaw prevented the blade from penetrating his jugular vein. He eventually recovered, though with serious scars on his face.

Seward's son Augustus and Sergeant George F. Robinson, a soldier assigned to Seward, were alerted by Fanny's screams and received stab wounds in struggling with Powell. As Augustus went for a pistol, Powell ran downstairs toward the door, where he encountered Emerick Hansell, a State Department messenger. Powell stabbed Hansell in the back, then ran outside exclaiming "I'm mad! I'm mad!". Screams from the house had frightened Herold, who ran off, leaving Powell to find his own way in an unfamiliar city.

Atzerodt fails to attack Johnson

Booth had assigned George Atzerodt to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson, who was staying at the Kirkwood House in Washington. Atzerodt was to go to Johnson's room at 10:15 p.m. and shoot him. On April 14, Atzerodt rented the room directly above Johnson's; the next day, he arrived there at the appointed time and, carrying a gun and knife, went to the bar downstairs, where he asked the bartender about Johnson's character and behavior. He eventually became drunk and wandered off through the streets, tossing his knife away at some point. He made his way to the Pennsylvania House Hotel by 2 am, where he obtained a room and went to sleep.

Earlier in the day, Booth had stopped by the Kirkwood House and left a note for Johnson: "I don't wish to disturb you. Are you at home? J. Wilkes Booth." One theory holds that Booth was trying to find out whether Johnson was expected at the Kirkwood that night; another holds that Booth, concerned that Atzerodt would fail to kill Johnson, intended the note to implicate Johnson in the conspiracy.

Reactions

Lincoln was mourned in both the North and South, and indeed around the world. Numerous foreign governments issued proclamations and declared periods of mourning on April 15. Lincoln was praised in sermons on Easter Sunday, which fell on the day after his death.

On April 18, mourners lined up seven abreast for a mile to view Lincoln in his walnut casket in the White House's black-draped East Room. Special trains brought thousands from other cities, some of whom slept on the Capitol's lawn. Hundreds of thousands watched the funeral procession on April 19, and millions more lined the 1,700-mile (2,700 km) route of the train which took Lincoln's remains through New York to Springfield, Illinois, often passing trackside tributes in the form of bands, bonfires, and hymn-singing.

Poet Walt Whitman composed "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd", "O Captain! My Captain!", and two other poems, to eulogize Lincoln.

Ulysses S. Grant called Lincoln "incontestably the greatest man I ever knew." Robert E. Lee expressed sadness. Southern-born Elizabeth Blair said that "Those of Southern born sympathies know now they have lost a friend willing and more powerful to protect and serve them than they can now ever hope to find again." African-American orator Frederick Douglass called the assassination an "unspeakable calamity".

British Foreign Secretary Lord Russell called Lincoln's death a "sad calamity." China's chief secretary of state for foreign affairs, Prince Kung, described himself as "inexpressibly shocked and startled". Ecuadorian President Gabriel Garcia Moreno said, "Never should I have thought that the noble country of Washington would be humiliated by such a black and horrible crime; nor should I ever have thought that Mr. Lincoln would come to such a horrible end, after having served his country with such wisdom and glory under so critical circumstances." The government of Liberia issued a proclamation calling Lincoln "not only the ruler of his own people, but a father to millions of a race stricken and oppressed." The government of Haiti condemned the assassination as a "horrid crime."

Flight and capture of the conspirators

Booth and Herold

Within half an hour of fleeing Ford's Theatre, Booth crossed the Navy Yard Bridge into Maryland. An army sentry questioned him about his late-night travel; Booth said that he was going home to the nearby town of Charles. Although it was forbidden for civilians to cross the bridge after 9 pm, the sentry let him through. David Herold made it across the same bridge less than an hour later and rendezvoused with Booth. After retrieving weapons and supplies previously stored at Surattsville, Herold and Booth rode to the home of Samuel A. Mudd, a local doctor, who splinted the leg Booth had broken in his escape, and later made a pair of crutches for Booth.

After a day at Mudd's house, Booth and Herold hired a local man to guide them to Samuel Cox's house. Cox, in turn, took them to Thomas Jones, a Confederate sympathizer who hid Booth and Herold in Zekiah Swamp for five days until they could cross the Potomac River. On the afternoon of April 24, they arrived at the farm of Richard H. Garrett, a tobacco farmer, in King George County, Virginia. Booth told Garrett he was a wounded Confederate soldier.

An April 15 letter to Navy Surgeon George Brainerd Todd from his brother tells of the rumors in Washington about Booth:

Today all the city is in mourning nearly every house being in black and I have not seen a smile, no business, and many a strong man I have seen in tears – Some reports say Booth is a prisoner, others that he has made his escape – but from orders received here, I believe he is taken, and during the night will be put on a Monitor for safe keeping – as a mob once raised now would know no end.

The hunt for the conspirators quickly became the largest in U.S. history, involving thousands of federal troops and countless civilians. Edwin M. Stanton personally directed the operation, authorizing rewards of $50,000 (equivalent to $800,000 in 2020) for Booth and $25,000 each for Herold and John Surratt.

Booth and Herold were sleeping at Garrett's farm on April 26 when soldiers from the 16th New York Cavalry arrived and surrounded the barn, then threatened to set fire to it. Herold surrendered, but Booth cried out, "I will not be taken alive!" The soldiers set fire to the barn and Booth scrambled for the back door with a rifle and pistol.

Sergeant Boston Corbett crept up behind the barn and shot Booth in "the back of the head about an inch below the spot where his [Booth's] shot had entered the head of Mr. Lincoln", severing his spinal cord. Booth was carried out onto the steps of the barn. A soldier poured water into his mouth, which he spat out, unable to swallow. Booth told the soldier, "Tell my mother I die for my country." Unable to move his limbs, he asked a soldier to lift his hands before his face and whispered his last words as he gazed at them: "Useless ... useless." He died on the porch of the Garrett farm two hours later. Corbett was initially arrested for disobeying orders from Stanton that Booth be taken alive if possible, but was later released and was largely considered a hero by the media and the public.

Others

Without Herold to guide him, Powell did not find his way back to the Surratt house until April 17. He told detectives waiting there that he was a ditch-digger hired by Mary Surratt, but she denied knowing him. Both were arrested. George Atzerodt hid at his cousin's farm in Germantown, Maryland, about 25 miles (40 km) northwest of Washington, where he was arrested April 20.

The remaining conspirators were arrested by month's end – except for John Surratt, who fled to Quebec where Roman Catholic priests hid him. In September, he boarded a ship to Liverpool, England, staying in the Catholic Church of the Holy Cross there. From there, he moved furtively through Europe until joining the Pontifical Zouaves in the Papal States. A friend from his school days recognized him there in early 1866 and alerted the U.S. government. Surratt was arrested by the Papal authorities but managed to escape under suspicious circumstances. He was finally captured by an agent of the United States in Egypt in November 1866.

Conspirators' trial and execution

Scores of persons were arrested, including many tangential associates of the conspirators and anyone having had even the slightest contact with Booth or Herold during their flight. These included Louis J. Weichmann, a boarder in Mrs. Surratt's house; Booth's brother Junius (in Cincinnati at the time of the assassination); theater owner John T. Ford; James Pumphrey, from whom Booth hired his horse; John M. Lloyd, the innkeeper who rented Mrs. Surratt's Maryland tavern and gave Booth and Herold weapons and supplies the night of April 14; and Samuel Cox and Thomas A. Jones, who helped Booth and Herold cross the Potomac. All were eventually released except:

- Samuel Arnold

- George Atzerodt

- David Herold

- Samuel Mudd

- Michael O'Laughlen

- Lewis Powell

- Edmund Spangler (a theater stagehand who had given Booth's horse to Burroughs to hold)

- Mary Surratt

The accused were tried by a military tribunal ordered by Johnson, who had succeeded to the presidency on Lincoln's death:

- Maj. Gen. David Hunter (presiding)

- Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace

- Brig. Gen. Robert Sanford Foster

- Brev. Maj. Gen. Thomas Maley Harris

- Brig. Gen. Albion P. Howe

- Brig. Gen. August Kautz

- Col. James A. Ekin

- Col. Charles H. Tompkins

- Lt. Col. David Ramsay Clendenin

The prosecution was led by U.S. Army Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt, assisted by Congressman John A. Bingham and Major Henry Lawrence Burnett.

The use of a military tribunal provoked criticism from Edward Bates and Gideon Welles, who believed that a civil court should have presided, but Attorney General James Speed pointed to the military nature of the conspiracy and the facts that the defendants acted as enemy combatants and that martial law was in force at the time in the District of Columbia. (In 1866, in Ex parte Milligan, the United States Supreme Court banned the use of military tribunals in places where civil courts were operational.) Only a simple majority of the jury was required for a guilty verdict and a two-thirds for a death sentence. There was no route for appeal other than to President Johnson.

The seven-week trial included the testimony of 366 witnesses. All of the defendants were found guilty on June 30. Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt were sentenced to death by hanging; Samuel Mudd, Samuel Arnold, and Michael O'Laughlen were sentenced to life in prison. Edmund Spangler was sentenced to six years. After sentencing Mary Surratt to hang, five jurors signed a letter recommending clemency, but Johnson refused to stop the execution; he later claimed he never saw the letter.

Mary Surratt, Powell, Herold, and Atzerodt were hanged in the Old Arsenal Penitentiary on July 7. Mary Surratt was the first woman executed by the United States government. O'Laughlen died in prison in 1867. Mudd, Arnold, and Spangler were pardoned in February 1869 by Johnson. Spangler, who died in 1875, always insisted his sole connection to the plot was that Booth asked him to hold his horse.

John Surratt stood trial in Washington in 1867. Four residents of Elmira, New York, claimed they had seen him there between April 13 and 15; fifteen others said they either saw him or someone who resembled him, in Washington (or traveling to or from Washington) on the day of the assassination. The jury could not reach a verdict, and John Surratt was released.