Parallel computing is a type of computation in which many calculations or processes are carried out simultaneously. Large problems can often be divided into smaller ones, which can then be solved at the same time. There are several different forms of parallel computing: bit-level, instruction-level, data, and task parallelism. Parallelism has long been employed in high-performance computing, but has gained broader interest due to the physical constraints preventing frequency scaling. As power consumption (and consequently heat generation) by computers has become a concern in recent years, parallel computing has become the dominant paradigm in computer architecture, mainly in the form of multi-core processors.

Parallel computing is closely related to concurrent computing—they are frequently used together, and often conflated, though the two are distinct: it is possible to have parallelism without concurrency (such as bit-level parallelism), and concurrency without parallelism (such as multitasking by time-sharing on a single-core CPU). In parallel computing, a computational task is typically broken down into several, often many, very similar sub-tasks that can be processed independently and whose results are combined afterwards, upon completion. In contrast, in concurrent computing, the various processes often do not address related tasks; when they do, as is typical in distributed computing, the separate tasks may have a varied nature and often require some inter-process communication during execution.

Parallel computers can be roughly classified according to the level at which the hardware supports parallelism, with multi-core and multi-processor computers having multiple processing elements within a single machine, while clusters, MPPs, and grids use multiple computers to work on the same task. Specialized parallel computer architectures are sometimes used alongside traditional processors, for accelerating specific tasks.

In some cases parallelism is transparent to the programmer, such as in bit-level or instruction-level parallelism, but explicitly parallel algorithms, particularly those that use concurrency, are more difficult to write than sequential ones, because concurrency introduces several new classes of potential software bugs, of which race conditions are the most common. Communication and synchronization between the different subtasks are typically some of the greatest obstacles to getting optimal parallel program performance.

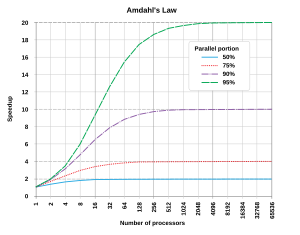

A theoretical upper bound on the speed-up of a single program as a result of parallelization is given by Amdahl's law.

Background

Traditionally, computer software has been written for serial computation. To solve a problem, an algorithm is constructed and implemented as a serial stream of instructions. These instructions are executed on a central processing unit on one computer. Only one instruction may execute at a time—after that instruction is finished, the next one is executed.

Parallel computing, on the other hand, uses multiple processing elements simultaneously to solve a problem. This is accomplished by breaking the problem into independent parts so that each processing element can execute its part of the algorithm simultaneously with the others. The processing elements can be diverse and include resources such as a single computer with multiple processors, several networked computers, specialized hardware, or any combination of the above. Historically parallel computing was used for scientific computing and the simulation of scientific problems, particularly in the natural and engineering sciences, such as meteorology. This led to the design of parallel hardware and software, as well as high performance computing.

Frequency scaling was the dominant reason for improvements in computer performance from the mid-1980s until 2004. The runtime of a program is equal to the number of instructions multiplied by the average time per instruction. Maintaining everything else constant, increasing the clock frequency decreases the average time it takes to execute an instruction. An increase in frequency thus decreases runtime for all compute-bound programs. However, power consumption P by a chip is given by the equation P = C × V 2 × F, where C is the capacitance being switched per clock cycle (proportional to the number of transistors whose inputs change), V is voltage, and F is the processor frequency (cycles per second). Increases in frequency increase the amount of power used in a processor. Increasing processor power consumption led ultimately to Intel's May 8, 2004 cancellation of its Tejas and Jayhawk processors, which is generally cited as the end of frequency scaling as the dominant computer architecture paradigm.

To deal with the problem of power consumption and overheating the major central processing unit (CPU or processor) manufacturers started to produce power efficient processors with multiple cores. The core is the computing unit of the processor and in multi-core processors each core is independent and can access the same memory concurrently. Multi-core processors have brought parallel computing to desktop computers. Thus parallelisation of serial programmes has become a mainstream programming task. In 2012 quad-core processors became standard for desktop computers, while servers have 10 and 12 core processors. From Moore's law it can be predicted that the number of cores per processor will double every 18–24 months. This could mean that after 2020 a typical processor will have dozens or hundreds of cores.

An operating system can ensure that different tasks and user programmes are run in parallel on the available cores. However, for a serial software programme to take full advantage of the multi-core architecture the programmer needs to restructure and parallelise the code. A speed-up of application software runtime will no longer be achieved through frequency scaling, instead programmers will need to parallelise their software code to take advantage of the increasing computing power of multicore architectures.

Amdahl's law and Gustafson's law

Optimally, the speedup from parallelization would be linear—doubling the number of processing elements should halve the runtime, and doubling it a second time should again halve the runtime. However, very few parallel algorithms achieve optimal speedup. Most of them have a near-linear speedup for small numbers of processing elements, which flattens out into a constant value for large numbers of processing elements.

The potential speedup of an algorithm on a parallel computing platform is given by Amdahl's law

where

- Slatency is the potential speedup in latency of the execution of the whole task;

- s is the speedup in latency of the execution of the parallelizable part of the task;

- p is the percentage of the execution time of the whole task concerning the parallelizable part of the task before parallelization.

Since Slatency < 1/(1 - p), it shows that a small part of the program which cannot be parallelized will limit the overall speedup available from parallelization. A program solving a large mathematical or engineering problem will typically consist of several parallelizable parts and several non-parallelizable (serial) parts. If the non-parallelizable part of a program accounts for 10% of the runtime (p = 0.9), we can get no more than a 10 times speedup, regardless of how many processors are added. This puts an upper limit on the usefulness of adding more parallel execution units. "When a task cannot be partitioned because of sequential constraints, the application of more effort has no effect on the schedule. The bearing of a child takes nine months, no matter how many women are assigned."

Amdahl's law only applies to cases where the problem size is fixed. In practice, as more computing resources become available, they tend to get used on larger problems (larger datasets), and the time spent in the parallelizable part often grows much faster than the inherently serial work. In this case, Gustafson's law gives a less pessimistic and more realistic assessment of parallel performance:

Both Amdahl's law and Gustafson's law assume that the running time of the serial part of the program is independent of the number of processors. Amdahl's law assumes that the entire problem is of fixed size so that the total amount of work to be done in parallel is also independent of the number of processors, whereas Gustafson's law assumes that the total amount of work to be done in parallel varies linearly with the number of processors.

Dependencies

Understanding data dependencies is fundamental in implementing parallel algorithms. No program can run more quickly than the longest chain of dependent calculations (known as the critical path), since calculations that depend upon prior calculations in the chain must be executed in order. However, most algorithms do not consist of just a long chain of dependent calculations; there are usually opportunities to execute independent calculations in parallel.

Let Pi and Pj be two program segments. Bernstein's conditions describe when the two are independent and can be executed in parallel. For Pi, let Ii be all of the input variables and Oi the output variables, and likewise for Pj. Pi and Pj are independent if they satisfy

Violation of the first condition introduces a flow dependency, corresponding to the first segment producing a result used by the second segment. The second condition represents an anti-dependency, when the second segment produces a variable needed by the first segment. The third and final condition represents an output dependency: when two segments write to the same location, the result comes from the logically last executed segment.

Consider the following functions, which demonstrate several kinds of dependencies:

1: function Dep(a, b) 2: c := a * b 3: d := 3 * c 4: end function

In this example, instruction 3 cannot be executed before (or even in parallel with) instruction 2, because instruction 3 uses a result from instruction 2. It violates condition 1, and thus introduces a flow dependency.

1: function NoDep(a, b) 2: c := a * b 3: d := 3 * b 4: e := a + b 5: end function

In this example, there are no dependencies between the instructions, so they can all be run in parallel.

Bernstein's conditions do not allow memory to be shared between different processes. For that, some means of enforcing an ordering between accesses is necessary, such as semaphores, barriers or some other synchronization method.

Race conditions, mutual exclusion, synchronization, and parallel slowdown

Subtasks in a parallel program are often called threads. Some parallel computer architectures use smaller, lightweight versions of threads known as fibers, while others use bigger versions known as processes. However, "threads" is generally accepted as a generic term for subtasks. Threads will often need synchronized access to an object or other resource, for example when they must update a variable that is shared between them. Without synchronization, the instructions between the two threads may be interleaved in any order. For example, consider the following program:

| Thread A | Thread B |

| 1A: Read variable V | 1B: Read variable V |

| 2A: Add 1 to variable V | 2B: Add 1 to variable V |

| 3A: Write back to variable V | 3B: Write back to variable V |

If instruction 1B is executed between 1A and 3A, or if instruction 1A is executed between 1B and 3B, the program will produce incorrect data. This is known as a race condition. The programmer must use a lock to provide mutual exclusion. A lock is a programming language construct that allows one thread to take control of a variable and prevent other threads from reading or writing it, until that variable is unlocked. The thread holding the lock is free to execute its critical section (the section of a program that requires exclusive access to some variable), and to unlock the data when it is finished. Therefore, to guarantee correct program execution, the above program can be rewritten to use locks:

| Thread A | Thread B |

| 1A: Lock variable V | 1B: Lock variable V |

| 2A: Read variable V | 2B: Read variable V |

| 3A: Add 1 to variable V | 3B: Add 1 to variable V |

| 4A: Write back to variable V | 4B: Write back to variable V |

| 5A: Unlock variable V | 5B: Unlock variable V |

One thread will successfully lock variable V, while the other thread will be locked out—unable to proceed until V is unlocked again. This guarantees correct execution of the program. Locks may be necessary to ensure correct program execution when threads must serialize access to resources, but their use can greatly slow a program and may affect its reliability.

Locking multiple variables using non-atomic locks introduces the possibility of program deadlock. An atomic lock locks multiple variables all at once. If it cannot lock all of them, it does not lock any of them. If two threads each need to lock the same two variables using non-atomic locks, it is possible that one thread will lock one of them and the second thread will lock the second variable. In such a case, neither thread can complete, and deadlock results.

Many parallel programs require that their subtasks act in synchrony. This requires the use of a barrier. Barriers are typically implemented using a lock or a semaphore. One class of algorithms, known as lock-free and wait-free algorithms, altogether avoids the use of locks and barriers. However, this approach is generally difficult to implement and requires correctly designed data structures.

Not all parallelization results in speed-up. Generally, as a task is split up into more and more threads, those threads spend an ever-increasing portion of their time communicating with each other or waiting on each other for access to resources. Once the overhead from resource contention or communication dominates the time spent on other computation, further parallelization (that is, splitting the workload over even more threads) increases rather than decreases the amount of time required to finish. This problem, known as parallel slowdown, can be improved in some cases by software analysis and redesign.

Fine-grained, coarse-grained, and embarrassing parallelism

Applications are often classified according to how often their subtasks need to synchronize or communicate with each other. An application exhibits fine-grained parallelism if its subtasks must communicate many times per second; it exhibits coarse-grained parallelism if they do not communicate many times per second, and it exhibits embarrassing parallelism if they rarely or never have to communicate. Embarrassingly parallel applications are considered the easiest to parallelize.

Flynn's taxonomy

Michael J. Flynn created one of the earliest classification systems for parallel (and sequential) computers and programs, now known as Flynn's taxonomy. Flynn classified programs and computers by whether they were operating using a single set or multiple sets of instructions, and whether or not those instructions were using a single set or multiple sets of data.

| Flynn's taxonomy |

|---|

| Single data stream |

| Multiple data streams |

| SIMD Subcategories |

| See also |

The single-instruction-single-data (SISD) classification is equivalent to an entirely sequential program. The single-instruction-multiple-data (SIMD) classification is analogous to doing the same operation repeatedly over a large data set. This is commonly done in signal processing applications. Multiple-instruction-single-data (MISD) is a rarely used classification. While computer architectures to deal with this were devised (such as systolic arrays), few applications that fit this class materialized. Multiple-instruction-multiple-data (MIMD) programs are by far the most common type of parallel programs.

According to David A. Patterson and John L. Hennessy, "Some machines are hybrids of these categories, of course, but this classic model has survived because it is simple, easy to understand, and gives a good first approximation. It is also—perhaps because of its understandability—the most widely used scheme."

Types of parallelism

Bit-level parallelism

From the advent of very-large-scale integration (VLSI) computer-chip fabrication technology in the 1970s until about 1986, speed-up in computer architecture was driven by doubling computer word size—the amount of information the processor can manipulate per cycle. Increasing the word size reduces the number of instructions the processor must execute to perform an operation on variables whose sizes are greater than the length of the word. For example, where an 8-bit processor must add two 16-bit integers, the processor must first add the 8 lower-order bits from each integer using the standard addition instruction, then add the 8 higher-order bits using an add-with-carry instruction and the carry bit from the lower order addition; thus, an 8-bit processor requires two instructions to complete a single operation, where a 16-bit processor would be able to complete the operation with a single instruction.

Historically, 4-bit microprocessors were replaced with 8-bit, then 16-bit, then 32-bit microprocessors. This trend generally came to an end with the introduction of 32-bit processors, which has been a standard in general-purpose computing for two decades. Not until the early 2000s, with the advent of x86-64 architectures, did 64-bit processors become commonplace.

Instruction-level parallelism

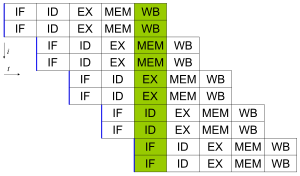

A computer program is, in essence, a stream of instructions executed by a processor. Without instruction-level parallelism, a processor can only issue less than one instruction per clock cycle (IPC < 1). These processors are known as subscalar processors. These instructions can be re-ordered and combined into groups which are then executed in parallel without changing the result of the program. This is known as instruction-level parallelism. Advances in instruction-level parallelism dominated computer architecture from the mid-1980s until the mid-1990s.

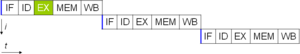

All modern processors have multi-stage instruction pipelines. Each stage in the pipeline corresponds to a different action the processor performs on that instruction in that stage; a processor with an N-stage pipeline can have up to N different instructions at different stages of completion and thus can issue one instruction per clock cycle (IPC = 1). These processors are known as scalar processors. The canonical example of a pipelined processor is a RISC processor, with five stages: instruction fetch (IF), instruction decode (ID), execute (EX), memory access (MEM), and register write back (WB). The Pentium 4 processor had a 35-stage pipeline.

Most modern processors also have multiple execution units. They usually combine this feature with pipelining and thus can issue more than one instruction per clock cycle (IPC > 1). These processors are known as superscalar processors. Superscalar processors differ from multi-core processors in that the several execution units are not entire processors (i.e. processing units). Instructions can be grouped together only if there is no data dependency between them. Scoreboarding and the Tomasulo algorithm (which is similar to scoreboarding but makes use of register renaming) are two of the most common techniques for implementing out-of-order execution and instruction-level parallelism.

Task parallelism

Task parallelisms is the characteristic of a parallel program that "entirely different calculations can be performed on either the same or different sets of data". This contrasts with data parallelism, where the same calculation is performed on the same or different sets of data. Task parallelism involves the decomposition of a task into sub-tasks and then allocating each sub-task to a processor for execution. The processors would then execute these sub-tasks concurrently and often cooperatively. Task parallelism does not usually scale with the size of a problem.

Superword level parallelism

Superword level parallelism is a vectorization technique based on loop unrolling and basic block vectorization. It is distinct from loop vectorization algorithms in that it can exploit parallelism of inline code, such as manipulating coordinates, color channels or in loops unrolled by hand.

Hardware

Memory and communication

Main memory in a parallel computer is either shared memory (shared between all processing elements in a single address space), or distributed memory (in which each processing element has its own local address space). Distributed memory refers to the fact that the memory is logically distributed, but often implies that it is physically distributed as well. Distributed shared memory and memory virtualization combine the two approaches, where the processing element has its own local memory and access to the memory on non-local processors. Accesses to local memory are typically faster than accesses to non-local memory. On the supercomputers, distributed shared memory space can be implemented using the programming model such as PGAS. This model allows processes on one compute node to transparently access the remote memory of another compute node. All compute nodes are also connected to an external shared memory system via high-speed interconnect, such as Infiniband, this external shared memory system is known as burst buffer, which is typically built from arrays of non-volatile memory physically distributed across multiple I/O nodes.

Computer architectures in which each element of main memory can be accessed with equal latency and bandwidth are known as uniform memory access (UMA) systems. Typically, that can be achieved only by a shared memory system, in which the memory is not physically distributed. A system that does not have this property is known as a non-uniform memory access (NUMA) architecture. Distributed memory systems have non-uniform memory access.

Computer systems make use of caches—small and fast memories located close to the processor which store temporary copies of memory values (nearby in both the physical and logical sense). Parallel computer systems have difficulties with caches that may store the same value in more than one location, with the possibility of incorrect program execution. These computers require a cache coherency system, which keeps track of cached values and strategically purges them, thus ensuring correct program execution. Bus snooping is one of the most common methods for keeping track of which values are being accessed (and thus should be purged). Designing large, high-performance cache coherence systems is a very difficult problem in computer architecture. As a result, shared memory computer architectures do not scale as well as distributed memory systems do.

Processor–processor and processor–memory communication can be implemented in hardware in several ways, including via shared (either multiported or multiplexed) memory, a crossbar switch, a shared bus or an interconnect network of a myriad of topologies including star, ring, tree, hypercube, fat hypercube (a hypercube with more than one processor at a node), or n-dimensional mesh.

Parallel computers based on interconnected networks need to have some kind of routing to enable the passing of messages between nodes that are not directly connected. The medium used for communication between the processors is likely to be hierarchical in large multiprocessor machines.

Classes of parallel computers

Parallel computers can be roughly classified according to the level at which the hardware supports parallelism. This classification is broadly analogous to the distance between basic computing nodes. These are not mutually exclusive; for example, clusters of symmetric multiprocessors are relatively common.

Multi-core computing

A multi-core processor is a processor that includes multiple processing units (called "cores") on the same chip. This processor differs from a superscalar processor, which includes multiple execution units and can issue multiple instructions per clock cycle from one instruction stream (thread); in contrast, a multi-core processor can issue multiple instructions per clock cycle from multiple instruction streams. IBM's Cell microprocessor, designed for use in the Sony PlayStation 3, is a prominent multi-core processor. Each core in a multi-core processor can potentially be superscalar as well—that is, on every clock cycle, each core can issue multiple instructions from one thread.

Simultaneous multithreading (of which Intel's Hyper-Threading is the best known) was an early form of pseudo-multi-coreism. A processor capable of concurrent multithreading includes multiple execution units in the same processing unit—that is it has a superscalar architecture—and can issue multiple instructions per clock cycle from multiple threads. Temporal multithreading on the other hand includes a single execution unit in the same processing unit and can issue one instruction at a time from multiple threads.

Symmetric multiprocessing

A symmetric multiprocessor (SMP) is a computer system with multiple identical processors that share memory and connect via a bus. Bus contention prevents bus architectures from scaling. As a result, SMPs generally do not comprise more than 32 processors. Because of the small size of the processors and the significant reduction in the requirements for bus bandwidth achieved by large caches, such symmetric multiprocessors are extremely cost-effective, provided that a sufficient amount of memory bandwidth exists.

Distributed computing

A distributed computer (also known as a distributed memory multiprocessor) is a distributed memory computer system in which the processing elements are connected by a network. Distributed computers are highly scalable. The terms "concurrent computing", "parallel computing", and "distributed computing" have a lot of overlap, and no clear distinction exists between them. The same system may be characterized both as "parallel" and "distributed"; the processors in a typical distributed system run concurrently in parallel.

Cluster computing

A cluster is a group of loosely coupled computers that work together closely, so that in some respects they can be regarded as a single computer. Clusters are composed of multiple standalone machines connected by a network. While machines in a cluster do not have to be symmetric, load balancing is more difficult if they are not. The most common type of cluster is the Beowulf cluster, which is a cluster implemented on multiple identical commercial off-the-shelf computers connected with a TCP/IP Ethernet local area network. Beowulf technology was originally developed by Thomas Sterling and Donald Becker. 87% of all Top500 supercomputers are clusters. The remaining are Massively Parallel Processors, explained below.

Because grid computing systems (described below) can easily handle embarrassingly parallel problems, modern clusters are typically designed to handle more difficult problems—problems that require nodes to share intermediate results with each other more often. This requires a high bandwidth and, more importantly, a low-latency interconnection network. Many historic and current supercomputers use customized high-performance network hardware specifically designed for cluster computing, such as the Cray Gemini network. As of 2014, most current supercomputers use some off-the-shelf standard network hardware, often Myrinet, InfiniBand, or Gigabit Ethernet.

Massively parallel computing

A massively parallel processor (MPP) is a single computer with many networked processors. MPPs have many of the same characteristics as clusters, but MPPs have specialized interconnect networks (whereas clusters use commodity hardware for networking). MPPs also tend to be larger than clusters, typically having "far more" than 100 processors. In an MPP, "each CPU contains its own memory and copy of the operating system and application. Each subsystem communicates with the others via a high-speed interconnect."

IBM's Blue Gene/L, the fifth fastest supercomputer in the world according to the June 2009 TOP500 ranking, is an MPP.

Grid computing

Grid computing is the most distributed form of parallel computing. It makes use of computers communicating over the Internet to work on a given problem. Because of the low bandwidth and extremely high latency available on the Internet, distributed computing typically deals only with embarrassingly parallel problems. Many distributed computing applications have been created, of which SETI@home and Folding@home are the best-known examples.

Most grid computing applications use middleware (software that sits between the operating system and the application to manage network resources and standardize the software interface). The most common distributed computing middleware is the Berkeley Open Infrastructure for Network Computing (BOINC). Often, distributed computing software makes use of "spare cycles", performing computations at times when a computer is idling.

Specialized parallel computers

Within parallel computing, there are specialized parallel devices that remain niche areas of interest. While not domain-specific, they tend to be applicable to only a few classes of parallel problems.

Reconfigurable computing with field-programmable gate arrays

Reconfigurable computing is the use of a field-programmable gate array (FPGA) as a co-processor to a general-purpose computer. An FPGA is, in essence, a computer chip that can rewire itself for a given task.

FPGAs can be programmed with hardware description languages such as VHDL or Verilog. However, programming in these languages can be tedious. Several vendors have created C to HDL languages that attempt to emulate the syntax and semantics of the C programming language, with which most programmers are familiar. The best known C to HDL languages are Mitrion-C, Impulse C, DIME-C, and Handel-C. Specific subsets of SystemC based on C++ can also be used for this purpose.

AMD's decision to open its HyperTransport technology to third-party vendors has become the enabling technology for high-performance reconfigurable computing. According to Michael R. D'Amour, Chief Operating Officer of DRC Computer Corporation, "when we first walked into AMD, they called us 'the socket stealers.' Now they call us their partners."

General-purpose computing on graphics processing units (GPGPU)

General-purpose computing on graphics processing units (GPGPU) is a fairly recent trend in computer engineering research. GPUs are co-processors that have been heavily optimized for computer graphics processing. Computer graphics processing is a field dominated by data parallel operations—particularly linear algebra matrix operations.

In the early days, GPGPU programs used the normal graphics APIs for executing programs. However, several new programming languages and platforms have been built to do general purpose computation on GPUs with both Nvidia and AMD releasing programming environments with CUDA and Stream SDK respectively. Other GPU programming languages include BrookGPU, PeakStream, and RapidMind. Nvidia has also released specific products for computation in their Tesla series. The technology consortium Khronos Group has released the OpenCL specification, which is a framework for writing programs that execute across platforms consisting of CPUs and GPUs. AMD, Apple, Intel, Nvidia and others are supporting OpenCL.

Application-specific integrated circuits

Several application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) approaches have been devised for dealing with parallel applications.

Because an ASIC is (by definition) specific to a given application, it can be fully optimized for that application. As a result, for a given application, an ASIC tends to outperform a general-purpose computer. However, ASICs are created by UV photolithography. This process requires a mask set, which can be extremely expensive. A mask set can cost over a million US dollars. (The smaller the transistors required for the chip, the more expensive the mask will be.) Meanwhile, performance increases in general-purpose computing over time (as described by Moore's law) tend to wipe out these gains in only one or two chip generations. High initial cost, and the tendency to be overtaken by Moore's-law-driven general-purpose computing, has rendered ASICs unfeasible for most parallel computing applications. However, some have been built. One example is the PFLOPS RIKEN MDGRAPE-3 machine which uses custom ASICs for molecular dynamics simulation.

Vector processors

A vector processor is a CPU or computer system that can execute the same instruction on large sets of data. Vector processors have high-level operations that work on linear arrays of numbers or vectors. An example vector operation is A = B × C, where A, B, and C are each 64-element vectors of 64-bit floating-point numbers. They are closely related to Flynn's SIMD classification.

Cray computers became famous for their vector-processing computers in the 1970s and 1980s. However, vector processors—both as CPUs and as full computer systems—have generally disappeared. Modern processor instruction sets do include some vector processing instructions, such as with Freescale Semiconductor's AltiVec and Intel's Streaming SIMD Extensions (SSE).

Software

Parallel programming languages

Concurrent programming languages, libraries, APIs, and parallel programming models (such as algorithmic skeletons) have been created for programming parallel computers. These can generally be divided into classes based on the assumptions they make about the underlying memory architecture—shared memory, distributed memory, or shared distributed memory. Shared memory programming languages communicate by manipulating shared memory variables. Distributed memory uses message passing. POSIX Threads and OpenMP are two of the most widely used shared memory APIs, whereas Message Passing Interface (MPI) is the most widely used message-passing system API. One concept used in programming parallel programs is the future concept, where one part of a program promises to deliver a required datum to another part of a program at some future time.

CAPS entreprise and Pathscale are also coordinating their effort to make hybrid multi-core parallel programming (HMPP) directives an open standard called OpenHMPP. The OpenHMPP directive-based programming model offers a syntax to efficiently offload computations on hardware accelerators and to optimize data movement to/from the hardware memory. OpenHMPP directives describe remote procedure call (RPC) on an accelerator device (e.g. GPU) or more generally a set of cores. The directives annotate C or Fortran codes to describe two sets of functionalities: the offloading of procedures (denoted codelets) onto a remote device and the optimization of data transfers between the CPU main memory and the accelerator memory.

The rise of consumer GPUs has led to support for compute kernels, either in graphics APIs (referred to as compute shaders), in dedicated APIs (such as OpenCL), or in other language extensions.

Automatic parallelization

Automatic parallelization of a sequential program by a compiler is the "holy grail" of parallel computing, especially with the aforementioned limit of processor frequency. Despite decades of work by compiler researchers, automatic parallelization has had only limited success.

Mainstream parallel programming languages remain either explicitly parallel or (at best) partially implicit, in which a programmer gives the compiler directives for parallelization. A few fully implicit parallel programming languages exist—SISAL, Parallel Haskell, SequenceL, System C (for FPGAs), Mitrion-C, VHDL, and Verilog.

Application checkpointing

As a computer system grows in complexity, the mean time between failures usually decreases. Application checkpointing is a technique whereby the computer system takes a "snapshot" of the application—a record of all current resource allocations and variable states, akin to a core dump—; this information can be used to restore the program if the computer should fail. Application checkpointing means that the program has to restart from only its last checkpoint rather than the beginning. While checkpointing provides benefits in a variety of situations, it is especially useful in highly parallel systems with a large number of processors used in high performance computing.

Algorithmic methods

As parallel computers become larger and faster, we are now able to solve problems that had previously taken too long to run. Fields as varied as bioinformatics (for protein folding and sequence analysis) and economics (for mathematical finance) have taken advantage of parallel computing. Common types of problems in parallel computing applications include:

- Dense linear algebra

- Sparse linear algebra

- Spectral methods (such as Cooley–Tukey fast Fourier transform)

- N-body problems (such as Barnes–Hut simulation)

- structured grid problems (such as Lattice Boltzmann methods)

- Unstructured grid problems (such as found in finite element analysis)

- Monte Carlo method

- Combinational logic (such as brute-force cryptographic techniques)

- Graph traversal (such as sorting algorithms)

- Dynamic programming

- Branch and bound methods

- Graphical models (such as detecting hidden Markov models and constructing Bayesian networks)

- Finite-state machine simulation

Fault tolerance

Parallel computing can also be applied to the design of fault-tolerant computer systems, particularly via lockstep systems performing the same operation in parallel. This provides redundancy in case one component fails, and also allows automatic error detection and error correction if the results differ. These methods can be used to help prevent single-event upsets caused by transient errors. Although additional measures may be required in embedded or specialized systems, this method can provide a cost-effective approach to achieve n-modular redundancy in commercial off-the-shelf systems.

History

The origins of true (MIMD) parallelism go back to Luigi Federico Menabrea and his Sketch of the Analytic Engine Invented by Charles Babbage.

In April 1958, Stanley Gill (Ferranti) discussed parallel programming and the need for branching and waiting. Also in 1958, IBM researchers John Cocke and Daniel Slotnick discussed the use of parallelism in numerical calculations for the first time. Burroughs Corporation introduced the D825 in 1962, a four-processor computer that accessed up to 16 memory modules through a crossbar switch. In 1967, Amdahl and Slotnick published a debate about the feasibility of parallel processing at American Federation of Information Processing Societies Conference. It was during this debate that Amdahl's law was coined to define the limit of speed-up due to parallelism.

In 1969, Honeywell introduced its first Multics system, a symmetric multiprocessor system capable of running up to eight processors in parallel. C.mmp, a multi-processor project at Carnegie Mellon University in the 1970s, was among the first multiprocessors with more than a few processors. The first bus-connected multiprocessor with snooping caches was the Synapse N+1 in 1984.

SIMD parallel computers can be traced back to the 1970s. The motivation behind early SIMD computers was to amortize the gate delay of the processor's control unit over multiple instructions. In 1964, Slotnick had proposed building a massively parallel computer for the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. His design was funded by the US Air Force, which was the earliest SIMD parallel-computing effort, ILLIAC IV. The key to its design was a fairly high parallelism, with up to 256 processors, which allowed the machine to work on large datasets in what would later be known as vector processing. However, ILLIAC IV was called "the most infamous of supercomputers", because the project was only one-fourth completed, but took 11 years and cost almost four times the original estimate. When it was finally ready to run its first real application in 1976, it was outperformed by existing commercial supercomputers such as the Cray-1.

Biological brain as massively parallel computer

In the early 1970s, at the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert started developing the Society of Mind theory, which views the biological brain as massively parallel computer. In 1986, Minsky published The Society of Mind, which claims that “mind is formed from many little agents, each mindless by itself”. The theory attempts to explain how what we call intelligence could be a product of the interaction of non-intelligent parts. Minsky says that the biggest source of ideas about the theory came from his work in trying to create a machine that uses a robotic arm, a video camera, and a computer to build with children's blocks.

Similar models (which also view the biological brain as a massively parallel computer, i.e., the brain is made up of a constellation of independent or semi-independent agents) were also described by:

- Thomas R. Blakeslee,

- Michael S. Gazzaniga,

- Robert E. Ornstein,

- Ernest Hilgard,

- Michio Kaku,

- George Ivanovich Gurdjieff,

- Neurocluster Brain Model.