| Electroconvulsive therapy | |

|---|---|

MECTA spECTrum 5000Q with electroencephalography (EEG) in a modern ECT suite | |

| Other names | Electroshock therapy |

| ICD-10-PCS | GZB |

| ICD-9-CM | 94.27 |

| MeSH | D004565 |

| OPS-301 code | 8-630 |

| MedlinePlus | 007474 |

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a psychiatric treatment where a generalized seizure (without muscular convulsions) is electrically induced to manage refractory mental disorders. Typically, 70 to 120 volts are applied externally to the patient's head resulting in approximately 800 milliamperes of direct current passed through the brain, for 100 milliseconds to 6 seconds duration, either from temple to temple (bilateral ECT) or from front to back of one side of the head (unilateral ECT).

The ECT procedure was first conducted in 1938 by Italian psychiatrist Ugo Cerletti and rapidly replaced less safe and effective forms of biological treatments in use at the time. ECT is often used with informed consent as a safe and effective intervention for major depressive disorder, mania, and catatonia. ECT machines were originally placed in the Class III category by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1976. They were re-classified as Class II devices, for treatment of catatonia, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder, in 2018.

Aside from effects on the brain, the general physical risks of ECT are similar to those of brief general anesthesia. Immediately following treatment, the most common adverse effects are confusion and transient memory loss. Among treatments for severely depressed pregnant women, ECT is one of the least harmful to the fetus.

A usual course of ECT involves multiple administrations, typically given two or three times per week until the patient is no longer suffering symptoms. ECT is administered under anesthesia with a muscle relaxant. ECT can differ in its application in three ways: electrode placement, treatment frequency, and the electrical waveform of the stimulus. These treatment parameters can pose significant differences in both adverse side effects and symptom remission in the treated patient.

Placement can be bilateral, where the electric current is passed from one side of the brain to the other, or unilateral, in which the current is solely passed across one hemisphere of the brain. High-dose unilateral ECT has some cognitive advantages compared to moderate-dose bilateral ECT while showing no difference in antidepressant efficacy.

ECT appears to work in the short term via an anticonvulsant effect primarily in the frontal lobes and longer term via neurotrophic effects primarily in the medial temporal lobe.

Medical use

ECT is used with informed consent in treatment-resistant major depressive disorder, treatment-resistant catatonia, prolonged or severe mania, and in conditions where "there is a need for rapid, definitive response because of the severity of a psychiatric or medical condition (e.g., when illness is characterized by stupor, marked psychomotor retardation, depressive delusions or hallucinations, or life-threatening physical exhaustion associated with mania)." It has also been used to treat autism in adults with an intellectual disability, yet findings from a systematic review found this an unestablished intervention.

Major depressive disorder

For major depressive disorder, despite a Canadian guideline and some experts arguing for using ECT as a first line treatment, ECT is generally used only when one or other treatments have failed, or in emergencies, such as imminent suicide. ECT has also been used in selected cases of depression occurring in the setting of multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's chorea, developmental delay, brain arteriovenous malformations, and hydrocephalus.

Efficacy

A meta-analysis on the effectiveness of ECT in unipolar and bipolar depression was conducted in 2012. Results indicated that although patients with unipolar depression and bipolar depression responded to other medical treatments very differently, both groups responded equally well to ECT. Overall remission rate for patients given a round of ECT treatment was 50.9% for those with unipolar depression and 53.2% for those with bipolar depression. The severity of each patient's depression was assessed at the same baseline in each group. Most of severely depressed patients respond to ECT.

In 2004, a meta-analytic review paper found in terms of efficacy, "a significant superiority of ECT in all comparisons: ECT versus simulated ECT, ECT versus placebo, ECT versus antidepressants in general, ECT versus tricyclics and ECT versus monoamine oxidase inhibitors."

In 2003, The UK ECT Review Group published a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing ECT to placebo and antidepressant drugs. This meta-analysis demonstrated a large effect size (high efficacy relative to the mean in terms of the standard deviation) for ECT versus placebo, and versus antidepressant drugs.

Compared with repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for people with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder, ECT relieves depression as shown by reducing the score on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression by about 15 points, while rTMS reduced it by 9 points.

The response rate is from 50 to 60% in treatment-resistant patients. Efficacity does not depend on depression subtype.

Follow-up

There is little agreement on the most appropriate follow-up to ECT for people with major depressive disorder. When ECT is followed by treatment with antidepressants, about 50% of people relapsed by 12 months following successful initial treatment with ECT, with about 37% relapsing within the first 6 months. About twice as many relapsed with no antidepressants. Most of the evidence for continuation therapy is with tricyclic antidepressants; evidence for relapse prevention with newer antidepressants is lacking.

Lithium has also been found to reduce the risk of relapse; especially in younger patients.

Catatonia

ECT is generally a second-line treatment for people with catatonia who do not respond to other treatments, but is a first-line treatment for severe or life-threatening catatonia. There is a plethora of evidence for its efficacy, notwithstanding a lack of randomised controlled trials, such that "the excellent efficacy of ECT in catatonia is generally acknowledged". For people with autism spectrum disorders who have catatonia, there is little published evidence about the efficacy of ECT; as of 2014 there were twelve case reports.

Mania

ECT is used to treat people who have severe or prolonged mania; NICE recommends it only in life-threatening situations or when other treatments have failed and as a second-line treatment for bipolar mania.

Schizophrenia

ECT is widely used worldwide in the treatment of schizophrenia, but in North America and Western Europe it is invariably used only in treatment resistant schizophrenia when symptoms show little response to antipsychotics; there is comprehensive research evidence for such practice. It is useful in the case of severe exacerbations of catatonic schizophrenia, whether excited or stuporous. There are also case reports of ECT improving persistent psychotic symptoms associated with Stimulant-induced psychosis.

Effects

Aside from effects in the brain, the general physical risks of ECT are similar to those of brief general anesthesia; the U.S. Surgeon General's report says that there are "no absolute health contraindications" to its use. Immediately following treatment, the most common adverse effects are confusion and memory loss. Some patients experience muscle soreness after ECT. The death rate during ECT is around 4 per 100,000 procedures. There is evidence and rationale to support giving low doses of benzodiazepines or otherwise low doses of general anesthetics, which induce sedation but not anesthesia, to patients to reduce adverse effects of ECT.

While there are no absolute contraindications for ECT, there is increased risk for patients who have unstable or severe cardiovascular conditions or aneurysms; who have recently had a stroke; who have increased intracranial pressure (for instance, due to a solid brain tumor), or who have severe pulmonary conditions, or who are generally at high risk for receiving anesthesia.

In adolescents, ECT is highly efficient for several psychiatric disorders, with few and relatively benign adverse effects.

Cognitive impairment

Cognitive impairment is sometimes noticed after ECT. It has been claimed by some non-medical authors that retrograde amnesia occurs to some extent in almost all patients receiving ECT. However, most experts consider this adverse effect relatively uncommon. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) report in 2001 acknowledges: “In some patients the recovery from retrograde amnesia will be incomplete, and evidence has shown that ECT can result in persistent or permanent memory loss”. After treatment, drug therapy is usually continued and some patients will continue to receive maintenance ECT treatments. It is the purported effects of ECT on long-term memory that give rise to much of the concern surrounding its use. However, the methods used to measure memory loss are generally poor, and their application to people with depression, who have cognitive deficits including problems with memory, have been problematic.

The acute effects of ECT can include amnesia, both retrograde (for events occurring before the treatment) and anterograde (for events occurring after the treatment). Memory loss and confusion are more pronounced with bilateral electrode placement rather than unilateral, and with outdated sine-wave rather than brief-pulse currents. The use of either constant or pulsing electrical impulses also varied the memory loss results in patients. Patients who received pulsing electrical impulses, as opposed to a steady flow, seemed to incur less memory loss. The vast majority of modern treatment uses brief pulse currents.

Retrograde amnesia is most marked for events occurring in the weeks or months before treatment, with one study showing that although some people lose memories from years prior to treatment, recovery of such memories was "virtually complete" by seven months post-treatment, with the only enduring loss being memories in the weeks and months prior to the treatment. Anterograde memory loss is usually limited to the time of treatment itself or shortly afterwards. In the weeks and months following ECT these memory problems gradually improve, but some people have persistent losses, especially with bilateral ECT. One published review summarizing the results of questionnaires about subjective memory loss found that between 29% and 55% of respondents believed they experienced long-lasting or permanent memory changes. In 2000, American psychiatrist Sarah Lisanby and colleagues found that bilateral ECT left patients with more persistently impaired memory of public events as compared to right unilateral ECT.

Effects on brain structure

Considerable controversy exists over the effects of ECT on brain tissue, although a number of mental health associations—including the APA—have concluded that there is no evidence that ECT causes structural brain damage. A 1999 report by the U.S. Surgeon General states: "The fears that ECT causes gross structural brain pathology have not been supported by decades of methodologically sound research in both humans and animals."

Many expert proponents of ECT maintain that the procedure is safe and does not cause brain damage. Dr. Charles Kellner, a prominent ECT researcher and former chief editor of the Journal of ECT, stated in a 2007 interview that, "There are a number of well-designed studies that show ECT does not cause brain damage and numerous reports of patients who have received a large number of treatments over their lifetime and have suffered no significant problems due to ECT." Dr. Kellner cites a study purporting to show an absence of cognitive impairment in eight subjects after more than 100 lifetime ECT treatments. Dr. Kellner stated "Rather than cause brain damage, there is evidence that ECT may reverse some of the damaging effects of serious psychiatric illness."

Effects in pregnancy

If steps are taken to decrease potential risks, ECT is generally accepted to be relatively safe during all trimesters of pregnancy, particularly when compared to pharmacological treatments. Suggested preparation for ECT during pregnancy includes a pelvic examination, discontinuation of nonessential anticholinergic medication, uterine tocodynamometry, intravenous hydration, and administration of a nonparticulate antacid. During ECT, elevation of the pregnant woman's right hip, external fetal cardiac monitoring, intubation, and avoidance of excessive hyperventilation are recommended. In many instances of active mood disorder during pregnancy, the risks of untreated symptoms may outweigh the risks of ECT. Potential complications of ECT during pregnancy can be minimized by modifications in technique. The use of ECT during pregnancy requires thorough evaluation of the patient's capacity for informed consent.

Effects on the heart

ECT can cause a lack of blood flow and oxygen to the heart, heart arrhythmia, and "persistent asystole". Deaths, however, are very rare after ECT: 6 per 100,000 treatments. If they do occur, cardiovascular complications are considered as causal in about 30%.

Procedure

The placement of electrodes, as well as the dose and duration of the stimulation is determined on a per-patient basis.

In unilateral ECT, both electrodes are placed on the same side of the patient's head. Unilateral ECT may be used first to minimize side effects such as memory loss.

In bilateral ECT, the two electrodes are placed on opposite sides of the head. Usually bitemporal placement is used, whereby the electrodes are placed on the temples. Uncommonly bifrontal placement is used; this involves positioning the electrodes on the patient's forehead, roughly above each eye.

Unilateral ECT is thought to cause fewer cognitive effects than bilateral treatment, but is less effective unless administered at higher doses. Most patients in the US and almost all in the UK receive bilateral ECT.

The electrodes deliver an electrical stimulus. The stimulus levels recommended for ECT are in excess of an individual's seizure threshold: about one and a half times seizure threshold for bilateral ECT and up to 12 times for unilateral ECT. Below these levels treatment may not be effective in spite of a seizure, while doses massively above threshold level, especially with bilateral ECT, expose patients to the risk of more severe cognitive impairment without additional therapeutic gains. Seizure threshold is determined by trial and error ("dose titration"). Some psychiatrists use dose titration, some still use "fixed dose" (that is, all patients are given the same dose) and others compromise by roughly estimating a patient's threshold according to age and sex. Older men tend to have higher thresholds than younger women, but it is not a hard and fast rule, and other factors, for example drugs, affect seizure threshold.

Immediately prior to treatment, a patient is given a short-acting anesthetic such as methohexital, etomidate, or thiopental, a muscle relaxant such as suxamethonium (succinylcholine), and occasionally atropine to inhibit salivation. In a minority of countries such as Japan, India, and Nigeria, ECT may be used without anesthesia. The Union Health Ministry of India recommended a ban on ECT without anesthesia in India's Mental Health Care Bill of 2010 and the Mental Health Care Bill of 2013. The practice was abolished in Turkey's largest psychiatric hospital in 2008.

The patient's EEG, ECG, and blood oxygen levels are monitored during treatment.

ECT is usually administered three times a week, on alternate days, over a course of two to four weeks.

Neuroimaging prior to ECT

Neuroimaging prior to ECT may be useful for detecting intracranial pressure or mass given that patients respond less when one of these conditions exist. Nonetheless it is not indicated due to high cost and low prevalence of these conditions in patients needing ECT.

Concurrent pharmacotherapy

Whether psychiatric medications are terminated prior to treatment or maintained, varies. However, drugs that are known to cause toxicity in combination with ECT, such as lithium, are discontinued, and benzodiazepines, which increase the seizure threshold, are either discontinued, a benzodiazepine antagonist is administered at each ECT session, or the ECT treatment is adjusted accordingly.

A 2009 RCT provides some evidence indicating that concurrent use of some antidepressant improves ECT efficacy.

Course

ECT is usually done from 6 to 12 times in 2 to 4 weeks but can sometimes exceed 12 rounds. It is also recommended to not do ECT more than 3 times per week.

The team

In the US, the medical team performing the procedure typically consists of a psychiatrist, an anesthetist, an ECT treatment nurse or qualified assistant, and one or more recovery nurses. Medical trainees may assist, but only under the direct supervision of credentialed attending physicians and staff.

Devices

Most modern ECT devices deliver a brief-pulse current, which is thought to cause fewer cognitive effects than the sine-wave currents which were originally used in ECT. A small minority of psychiatrists in the US still use sine-wave stimuli. Sine-wave is no longer used in the UK or Ireland. Typically, the electrical stimulus used in ECT is about 800 milliamps and has up to several hundred watts, and the current flows for between one and six seconds.

In the US, ECT devices are manufactured by two companies, Somatics, which is owned by psychiatrists Richard Abrams and Conrad Swartz, and Mecta. In the UK, the market for ECT devices was long monopolized by Ectron Ltd, which was set up by psychiatrist Robert Russell.

Mechanism of action

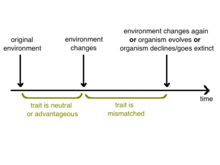

Despite decades of research, the exact mechanism of action of ECT remains elusive. Neuroimaging studies in people who have had ECT, investigating differences between responders and nonresponders, and people who relapse, find that responders have anticonvulsant effects mostly in the frontal lobes, which corresponds to immediate responses, and neurotrophic effects primarily in the medial temporal lobe. The anticonvulsant effects are decreased blood flow and decreased metabolism, while the neurotrophic effects are opposite - increased perfusion and metabolism, as well as increased volume of the hippocampus.

A recently proposed mechanism of action is that the seizures induced by ECT cause a profound change in sleep architecture; it is this change in the state of the organism that drives the therapeutic effects of ECT and not any simple change in the release of neurotransmitters, neurotrophic factors and/or hormones.

Use

As of 2001, it was estimated that about one million people received ECT annually.

There is wide variation in ECT use between different countries, different hospitals, and different psychiatrists. International practice varies considerably from widespread use of the therapy in many Western countries to a small minority of countries that do not use ECT at all, such as Slovenia.

About 70 percent of ECT patients are women. This may be due to the fact that women are more likely to be diagnosed with depression. Older and more affluent patients are also more likely to receive ECT. The use of ECT is not as common in ethnic minorities.

Sarah Hall reports, "ECT has been dogged by conflict between psychiatrists who swear by it, and some patients and families of patients who say that their lives have been ruined by it. It is controversial in some European countries such as the Netherlands and Italy, where its use is severely restricted".

United States

ECT became popular in the US in the 1940s. At the time, psychiatric hospitals were overrun with patients whom doctors were desperate to treat and cure. Whereas lobotomies would reduce a patient to a more manageable submissive state, ECT helped to improve mood in those with severe depression. A survey of psychiatric practice in the late 1980s found that an estimated 100,000 people received ECT annually, with wide variation between metropolitan statistical areas. Accurate statistics about the frequency, context and circumstances of ECT in the US are difficult to obtain because only a few states have reporting laws that require the treating facility to supply state authorities with this information. In 13 of the 50 states, the practice of ECT is regulated by law. In the mid-1990s in Texas, ECT was used in about one third of psychiatric facilities and given to about 1,650 people annually. Usage of ECT has since declined slightly; in 2000–01 ECT was given to about 1500 people aged from 16 to 97 (in Texas it is illegal to give ECT to anyone under sixteen). ECT is more commonly used in private psychiatric hospitals than in public hospitals, and minority patients are underrepresented in the ECT statistics. In the United States, ECT is usually given three times a week; in the United Kingdom, it is usually given twice a week. Occasionally it is given on a daily basis. A course usually consists of 6–12 treatments, but may be more or fewer. Following a course of ECT some patients may be given continuation or maintenance ECT with further treatments at weekly, fortnightly or monthly intervals. A few psychiatrists in the US use multiple-monitored ECT (MMECT), where patients receive more than one treatment per anesthetic. Electroconvulsive therapy is not a required subject in US medical schools and not a required skill in psychiatric residency training. Privileging for ECT practice at institutions is a local option: no national certification standards are established, and no ECT-specific continuing training experiences are required of ECT practitioners.

United Kingdom

In the UK in 1980, an estimated 50,000 people received ECT annually, with use declining steadily since then to about 12,000 per annum in 2002. It is still used in nearly all psychiatric hospitals, with a survey of ECT use from 2002 finding that 71 percent of patients were women and 46 percent were over 65 years of age. Eighty-one percent had a diagnosis of mood disorder; schizophrenia was the next most common diagnosis. Sixteen percent were treated without their consent. In 2003, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, a government body which was set up to standardize treatment throughout the National Health Service in England and Wales, issued guidance on the use of ECT. Its use was recommended "only to achieve rapid and short-term improvement of severe symptoms after an adequate trial of treatment options has proven ineffective and/or when the condition is considered to be potentially life-threatening in individuals with severe depressive illness, catatonia or a prolonged manic episode".

The guidance received a mixed reception. It was welcomed by an editorial in the British Medical Journal but the Royal College of Psychiatrists launched an unsuccessful appeal. The NICE guidance, as the British Medical Journal editorial points out, is only a policy statement and psychiatrists may deviate from it if they see fit. Adherence to standards has not been universal in the past. A survey of ECT use in 1980 found that more than half of ECT clinics failed to meet minimum standards set by the Royal College of Psychiatrists, with a later survey in 1998 finding that minimum standards were largely adhered to, but that two-thirds of clinics still fell short of current guidelines, particularly in the training and supervision of junior doctors involved in the procedure. A voluntary accreditation scheme, ECTAS, was set up in 2004 by the Royal College, and as of 2017 the vast majority of ECT clinics in England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland have signed up.

The Mental Health Act 2007 allows people to be treated against their will. This law has extra protections regarding ECT. A patient capable of making the decision can decline the treatment, and in that case treatment cannot be given unless it will save that patient's life or is immediately necessary to prevent deterioration of the patient's condition. A patient may not be capable of making the decision (they "lack capacity"), and in that situation ECT can be given if it is appropriate and also if there are no advance directives that prevent the use of ECT.

China

ECT was introduced in China in the early 1950s and while it was originally practiced without anesthesia, as of 2012 almost all procedures were conducted with it. As of 2012, there are approximately 400 ECT machines in China, and 150,000 ECT treatments are performed each year. Chinese national practice guidelines recommend ECT for the treatment of schizophrenia, depressive disorders, and bipolar disorder and in the Chinese literature, ECT is an effective treatment for schizophrenia and mood disorders.

Although the Chinese government stopped classifying homosexuality as an illness in 2001, electroconvulsive therapy is still used by some establishments as a form of "conversion therapy". Alleged Internet addiction (or general unruliness) in adolescents is also known to have been treated with ECT, sometimes without anestheia, most notably by Yang Yongxin. The practice was banned in 2009 after news on Yang broke out.

History

As early as the 16th century, agents to induce seizures were used to treat psychiatric conditions. In 1785, the therapeutic use of seizure induction was documented in the London Medical and Surgical Journal. As to its earliest antecedents one doctor claims 1744 as the dawn of electricity's therapeutic use, as documented in the first issue of Electricity and Medicine. Treatment and cure of hysterical blindness was documented eleven years later. Benjamin Franklin wrote that an electrostatic machine cured "a woman of hysterical fits." By 1801, James Lind as well as Giovanni Aldini had used galvanism to treat patients suffering from various mental disorders. G.B.C. Duchenne, the mid-19th century "Father of Electrotherapy", said its use was integral to a neurological practice.

In the second half of the 19th century, such efforts were frequent enough in British asylums as to make it notable.

Convulsive therapy was introduced in 1934 by Hungarian neuropsychiatrist Ladislas J. Meduna who, believing mistakenly that schizophrenia and epilepsy were antagonistic disorders, induced seizures first with camphor and then metrazol (cardiazol). Meduna is thought to be the father of convulsive therapy. In 1937, the first international meeting on schizophrenia and convulsive therapy was held in Switzerland by the Swiss psychiatrist Max Müller. The proceedings were published in the American Journal of Psychiatry and, within three years, cardiazol convulsive therapy was being used worldwide. Italian Professor of neuropsychiatry Ugo Cerletti, who had been using electric shocks to produce seizures in animal experiments, and his assistant Lucio Bini at Sapienza University of Rome developed the idea of using electricity as a substitute for metrazol in convulsive therapy and, in 1938, experimented for the first time on a person affected by delusions. It was believed early on that inducing convulsions aided in helping those with severe schizophrenia but later found to be most useful with affective disorders such as depression. Cerletti had noted a shock to the head produced convulsions in dogs. The idea to use electroshock on humans came to Cerletti when he saw how pigs were given an electric shock before being butchered to put them in an anesthetized state. Cerletti and Bini practiced until they felt they had the right parameters needed to have a successful human trial. Once they started trials on patients, they found that after 10-20 treatments the results were significant. Patients had much improved. A positive side effect to the treatment was retrograde amnesia. It was because of this side effect that patients could not remember the treatments and had no ill feelings toward it. ECT soon replaced metrazol therapy all over the world because it was cheaper, less frightening and more convenient. Cerletti and Bini were nominated for a Nobel Prize but did not receive one. By 1940, the procedure was introduced to both England and the US. In Germany and Austria, it was promoted by Friedrich Meggendorfer. Through the 1940s and 1950s, the use of ECT became widespread. At the time the ECT device was patented and commercialized abroad, the two Italian inventors had competitive tensions that damaged their relationship. In the 1960s, despite a climate of condemnation, the original Cerletti-Bini ECT apparatus prototype was hotly contended by scientific museums between Italy and the USA The ECT apparatus prototype is now owned and displayed by the Sapienza Museum of the History of Medicine in Rome.

In the early 1940s, in an attempt to reduce the memory disturbance and confusion associated with treatment, two modifications were introduced: the use of unilateral electrode placement and the replacement of sinusoidal current with brief pulse. It took many years for brief-pulse equipment to be widely adopted. In the 1940s and early 1950s ECT, was usually given in "unmodified" form, without muscle relaxants, and the seizure resulted in a full-scale convulsion. A rare but serious complication of unmodified ECT was fracture or dislocation of the long bones. In the 1940s, psychiatrists began to experiment with curare, the muscle-paralysing South American poison, in order to modify the convulsions. The introduction of suxamethonium (succinylcholine), a safer synthetic alternative to curare, in 1951 led to the more widespread use of "modified" ECT. A short-acting anesthetic was usually given in addition to the muscle relaxant in order to spare patients the terrifying feeling of suffocation that can be experienced with muscle relaxants.

The steady growth of antidepressant use along with negative depictions of ECT in the mass media led to a marked decline in the use of ECT during the 1950s to the 1970s. The Surgeon General stated there were problems with electroshock therapy in the initial years before anesthesia was routinely given, and that "these now-antiquated practices contributed to the negative portrayal of ECT in the popular media." The New York Times described the public's negative perception of ECT as being caused mainly by one movie: "For Big Nurse in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, it was a tool of terror, and, in the public mind, shock therapy has retained the tarnished image given it by Ken Kesey's novel: dangerous, inhumane and overused".

In 1976, Dr. Blatchley demonstrated the effectiveness of his constant current, brief pulse device ECT. This device eventually largely replaced earlier devices because of the reduction in cognitive side effects, although as of 2012 some ECT clinics still were using sine-wave devices. The 1970s saw the publication of the first American Psychiatric Association (APA) task force report on electroconvulsive therapy (to be followed by further reports in 1990 and 2001). The report endorsed the use of ECT in the treatment of depression. The decade also saw criticism of ECT. Specifically, critics pointed to shortcomings such as noted side effects, the procedure being used as a form of abuse, and uneven application of ECT. The use of ECT declined until the 1980s, "when use began to increase amid growing awareness of its benefits and cost-effectiveness for treating severe depression". In 1985, the National Institute of Mental Health and National Institutes of Health convened a consensus development conference on ECT and concluded that, while ECT was the most controversial treatment in psychiatry and had significant side-effects, it had been shown to be effective for a narrow range of severe psychiatric disorders.

Because of the backlash noted previously, national institutions reviewed past practices and set new standards. In 1978, the American Psychiatric Association released its first task force report in which new standards for consent were introduced and the use of unilateral electrode placement was recommended. The 1985 NIMH Consensus Conference confirmed the therapeutic role of ECT in certain circumstances. The American Psychiatric Association released its second task force report in 1990 where specific details on the delivery, education, and training of ECT were documented. Finally, in 2001 the American Psychiatric Association released its latest task force report. This report emphasizes the importance of informed consent, and the expanded role that the procedure has in modern medicine. By 2017, ECT was routinely covered by insurance companies for providing the "biggest bang for the buck" for otherwise intractable cases of severe mental illness, was receiving favorable media coverage, and was being provided in regional medical centers.

Though ECT use declined with the advent of modern antidepressants, there has been a resurgence of ECT with new modern technologies and techniques. Modern shock voltage is given for a shorter duration of 0.5 milliseconds where conventional brief pulse is 1.5 milliseconds.

Society and culture

Controversy

Surveys of public opinion, the testimony of former patients, legal restrictions on the use of ECT and disputes as to the efficacy, ethics and adverse effects of ECT within the psychiatric and wider medical community indicate that the use of ECT remains controversial. This is reflected in the January 2011 vote by the FDA's Neurological Devices Advisory Panel to recommend that FDA maintain ECT devices in the Class III device category for high risk devices, except for patients suffering from catatonia, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder. This may result in the manufacturers of such devices having to do controlled trials on their safety and efficacy for the first time. In justifying their position, panelists referred to the memory loss associated with ECT and the lack of long-term data.

Legal status

Informed consent

The World Health Organization (2005) advises that ECT should be used only with the informed consent of the patient (or their guardian if their incapacity to consent has been established).

In the US, this doctrine places a legal obligation on a doctor to make a patient aware of the reason for treatment, the risks and benefits of a proposed treatment, the risks and benefits of alternative treatment, and the risks and benefits of receiving no treatment. The patient is then given the opportunity to accept or reject the treatment. The form states how many treatments are recommended and also makes the patient aware that consent may be revoked and treatment discontinued at any time during a course of ECT. The US Surgeon General's Report on Mental Health states that patients should be warned that the benefits of ECT are short-lived without active continuation treatment in the form of drugs or further ECT, and that there may be some risk of permanent, severe memory loss after ECT. The report advises psychiatrists to involve patients in discussion, possibly with the aid of leaflets or videos, both before and during a course of ECT.

To demonstrate what he believes should be required to fully satisfy the legal obligation for informed consent, one psychiatrist, working for an anti-psychiatry organisation, has formulated his own consent form using the consent form developed and enacted by the Texas Legislature as a model.

According to the US Surgeon General, involuntary treatment is uncommon in the US and is typically used only in cases of great extremity, and only when all other treatment options have been exhausted. The use of ECT is believed to be a potentially life-saving treatment.

In one of the few jurisdictions where recent statistics on ECT usage are available, a national audit of ECT by the Scottish ECT Accreditation Network indicated that 77% of patients who received the treatment in 2008 were capable of giving informed consent.

In the UK, in order for consent to be valid it requires an explanation in "broad terms" of the nature of the procedure and its likely effects. One review from 2005 found that only about half of patients felt they were given sufficient information about ECT and its adverse effects and another survey found that about fifty percent of psychiatrists and nurses agreed with them.

A 2005 study published in the British Journal of Psychiatry described patients' perspectives on the adequacy of informed consent before ECT. The study found that "About half (45–55%) of patients reported they were given an adequate explanation of ECT, implying a similar percentage felt they were not." The authors also stated:

Approximately a third did not feel they had freely consented to ECT even when they had signed a consent form. The proportion who feel they did not freely choose the treatment has actually increased over time. The same themes arise whether the patient had received treatment a year ago or 30 years ago. Neither current nor proposed safeguards for patients are sufficient to ensure informed consent with respect to ECT, at least in England and Wales.

Involuntary ECT

Procedures for involuntary ECT vary from country to country depending on local mental health laws.

United States

In most states in the US, a judicial order following a formal hearing is needed before a patient can be forced to undergo involuntary ECT. However, ECT can also be involuntarily administered in situations with less immediate danger. Suicidal intent is a common justification for its involuntary use, especially when other treatments are ineffective.

United Kingdom

Until 2007 in England and Wales, the Mental Health Act 1983 allowed the use of ECT on detained patients whether or not they had capacity to consent to it. However, following amendments which took effect in 2007, ECT may not generally be given to a patient who has capacity and refuses it, irrespective of his or her detention under the Act. In fact, even if a patient is deemed to lack capacity, if they made a valid advance decision refusing ECT then they should not be given it; and even if they do not have an advance decision, the psychiatrist must obtain an independent second opinion (which is also the case if the patient is under age of consent). However, there is an exception regardless of consent and capacity; under Section 62 of the Act, if the treating psychiatrist says the need for treatment is urgent they may start a course of ECT without authorization. From 2003 to 2005, about 2,000 people a year in England and Wales were treated without their consent under the Mental Health Act. Concerns have been raised by the official regulator that psychiatrists are too readily assuming that patients have the capacity to consent to their treatments, and that there is a worrying lack of independent advocacy. In Scotland, the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 also gives patients with capacity the right to refuse ECT.

Regulation

In the US, ECT devices came into existence prior to medical devices being regulated by the Food and Drug Administration. In 1976, the Medical Device Regulation Act required the FDA to retrospectively review already existing devices, classify them, and determine whether clinical trials were needed to prove efficacy and safety. The FDA initially classified the devices used to administer ECT as Class III medical devices. In 2014, the American Psychiatric Association petitioned the FDA to reclassify ECT devices from Class III (high-risk) to Class II (medium-risk), which would significantly improve access to an effective and potentially lifesaving treatment. A similar reclassification proposal in 2010 met significant resistance from anti-psychiatry groups and did not pass. In 2018, the FDA re-classified ECT devices as Class II devices when used to treat catatonia or a severe major depressive episode associated with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder.

Public perception

A questionnaire survey of 379 members of the general public in Australia indicated that more than 60% of respondents had some knowledge about the main aspects of ECT. Participants were generally opposed to the use of ECT on depressed individuals with psychosocial issues, on children, and on involuntary patients. Public perceptions of ECT were found to be mainly negative. A sample of the general public, medical students, and psychiatry trainees in the United Kingdom found that the psychiatry trainees were more knowledgeable and had more favorable opinions of ECT than did the other groups. More members of the general public believed that ECT was used for control or punishment purposes than medical students or psychiatry trainees.

Famous cases

Ernest Hemingway, an American author, died by suicide shortly after ECT at the Mayo Clinic in 1961. He is reported to have said to his biographer, "Well, what is the sense of ruining my head and erasing my memory, which is my capital, and putting me out of business? It was a brilliant cure but we lost the patient."

Robert Pirsig suffered a nervous breakdown and spent time in and out of psychiatric hospitals between 1961 and 1963. He was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and clinical depression as a result of an evaluation conducted by psychoanalysts, and was treated with electroconvulsive therapy on numerous occasions, a treatment he discusses in his novel, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.

Thomas Eagleton, United States Senator from Missouri, was dropped from the Democratic ticket in the 1972 United States Presidential Election as the party's Vice Presidential candidate after it was revealed that he had received electroshock treatment in the past for depression. Presidential nominee George McGovern replaced him with Sargent Shriver, and later went on to lose by a landslide to Richard Nixon.

American surgeon and award-winning author Sherwin B. Nuland is another notable person who has undergone ECT. In his 40s, this successful surgeon's depression became so severe that he had to be institutionalized. After exhausting all treatment options, a young resident assigned to his case suggested ECT, which ended up being successful. Author David Foster Wallace also received ECT for many years, beginning as a teenager, before his suicide at age 46.

New Zealand author Janet Frame experienced both insulin coma therapy and ECT (but without the use of anesthesia or muscle relaxants). She wrote about this in her autobiography, An Angel at My Table (1984), which was later adapted into a film (1990).

American actor Carrie Fisher wrote about her experience with memory loss after ECT treatments in her memoir Wishful Drinking.

Fictional examples

Electroconvulsive therapy has been depicted in fiction, including fictional works partly based on true experiences. These include Sylvia Plath's autobiographical novel, The Bell Jar, Ken Loach's film Family Life, and Ken Kesey's novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest; Kesey's novel is a direct product of his time working the graveyard shift as an orderly at a mental health facility in Menlo Park, California.

In the 2000 film Requiem for a Dream, Sarah Goldfarb receives "unmodified" electroconvulsive therapy after experiencing severe amphetamine psychosis following prolonged stimulant abuse. Unlike typical ECT treatment, she is given no anesthetic or medication before.

In the 2014 TV series Constantine, the protagonist John Constantine is institutionalized and specifically requests electroconvulsive therapy as an attempt to alleviate or resolve his mental problems.

In the final episode of Season 1 of the US television series Homeland, Carrie Mathison receives electroconvulsive therapy in an attempt to alleviate her bipolar disorder.

The musical Next to Normal revolves around the family of a woman who undergoes the procedure.

In the HBO series Six Feet Under season 5, George undergoes an ECT treatment to deal with his increasing paranoia. The depiction is shown realistically, with an actual ECT machine.

In the WB/CW TV series Smallville, Lionel Luthor condemns his son Lex Luthor to electroshock therapy to remove Lex's short-term memory of a murder he discovered Lionel committed.

In the Netflix series Stranger Things, Eleven's mother is given electroshock therapy to silence her.

Electroshock therapy is used on various characters throughout season 2 of American Horror Story.

Special populations

Sex difference

Throughout the history of ECT, women have received it two to three times as often as men. Currently, about 70 percent of ECT patients are women. This may be due to the fact that women are more likely to be diagnosed with depression. A 1974 study of ECT in Massachusetts reported that women made up 69 percent of those given ECT. The Ministry of Health in Canada reported that from 1999 until 2000 in the province of Ontario, women were 71 percent of those given ECT in provincial psychiatric institutions, and 75 percent of the total ECT given was given to women.