| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | kləˈnazɪpam |

| Trade names | Klonopin, Rivotril, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682279 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Physical: Moderate to High Psychological: Moderate to High |

| Addiction liability | Moderate |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular, intravenous, sublingual |

| Drug class | Benzodiazepine |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 90% |

| Protein binding | ≈85% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP3A) |

| Metabolites | 7-aminoclonazepam; 7-acetaminoclonazepam; 3-hydroxy clonazepam |

| Onset of action | Within an hour |

| Elimination half-life | 19–60 hours |

| Duration of action | 6–12 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

|---|---|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.015.088 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

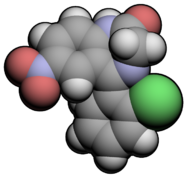

| Formula | C15H10ClN3O3 |

| Molar mass | 315.71 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

Clonazepam, sold under the brand Klonopin among others, is a medication used to prevent and treat seizures, panic disorder, anxiety, and the movement disorder known as akathisia. It is a tranquilizer of the benzodiazepine class. It is taken by mouth. Effects begin within one hour and last between six and twelve hours.

Common side effects include sleepiness, poor coordination, and agitation. Long-term use may result in tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal symptoms if stopped abruptly. Dependence occurs in one-third of people who take clonazepam for longer than four weeks. There is an increased risk of suicide, particularly in people who are already depressed. If used during pregnancy it may result in harm to the fetus. Clonazepam binds to GABAA receptors, thus increasing the effect of the chief inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

Clonazepam was patented in 1960 and went on sale in 1975 in the United States from Roche. It is available as a generic medication. In 2018, it was the 47th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 17 million prescriptions. In many areas of the world it is commonly used as a recreational drug.

Medical uses

Clonazepam is prescribed for short term management of epilepsy, anxiety, and panic disorder with or without agoraphobia.

Seizures

Clonazepam, like other benzodiazepines, while being a first-line treatment for acute seizures, is not suitable for the long-term treatment of seizures due to the development of tolerance to the anticonvulsant effects.

Clonazepam has been found effective in treating epilepsy in children, and the inhibition of seizure activity seemed to be achieved at low plasma levels of clonazepam. As a result, clonazepam is sometimes used for certain rare childhood epilepsies; however, it has been found to be ineffective in the control of infantile spasms. Clonazepam is mainly prescribed for the acute management of epilepsies. Clonazepam has been found to be effective in the acute control of non-convulsive status epilepticus; however, the benefits tended to be transient in many people, and the addition of phenytoin for lasting control was required in these patients.

It is also approved for treatment of typical and atypical absences (seizures), infantile myoclonic, myoclonic, and akinetic seizures. A subgroup of people with treatment resistant epilepsy may benefit from long-term use of clonazepam; the benzodiazepine clorazepate may be an alternative due to its slow onset of tolerance.

Anxiety disorders

- Panic disorder with or without agoraphobia.

- Clonazepam has also been found effective in treating other anxiety disorders, such as social phobia, but this is an off-label use.

The effectiveness of clonazepam in the short-term treatment of panic disorder has been demonstrated in controlled clinical trials. Some long-term trials have suggested a benefit of clonazepam for up to three years without the development of tolerance but these trials were not placebo-controlled. Clonazepam is also effective in the management of acute mania.

Muscle disorders

Restless legs syndrome can be treated using clonazepam as a third-line treatment option as the use of clonazepam is still investigational. Bruxism also responds to clonazepam in the short-term. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder responds well to low doses of clonazepam.

- The treatment of acute and chronic akathisia induced by neuroleptics, also called antipsychotics.

- Spasticity related to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

- Alcohol withdrawal syndrome

Other

- Benzodiazepines, such as clonazepam, are sometimes used for the treatment of mania or acute psychosis-induced aggression. In this context, benzodiazepines are given either alone, or in combination with other first-line drugs such as lithium, haloperidol or risperidone. The effectiveness of taking benzodiazepines along with antipsychotic medication is unknown, and more research is needed to determine if benzodiazepines are more effective than antipsychotics when urgent sedation is required.

- Hyperekplexia

- Many forms of parasomnia and other sleep disorders are treated with clonazepam.

- It is not effective for preventing migraines.

Contraindications

Coma; current alcohol use disorder; current substance use disorder; and respiratory depression.

Adverse effects

In September 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required the boxed warning be updated for all benzodiazepine medicines to describe the risks of abuse, misuse, addiction, physical dependence, and withdrawal reactions consistently across all the medicines in the class.

Common

Less common

- Confusion

- Irritability and aggression

- Psychomotor agitation

- Lack of motivation

- Loss of libido

- Impaired motor function

- Impaired coordination

- Impaired balance

- Dizziness

- Cognitive impairments

- Hallucinations.

- Short-term memory loss

- Anterograde amnesia (common with higher doses)

- Some users report hangover-like symptoms of drowsiness, headaches, sluggishness, and irritability upon waking up if the medication was taken before sleep. This is likely the result of the medication's long half-life, which continues to affect the user after waking up. While benzodiazepines induce sleep, they tend to reduce the quality of sleep by suppressing or disrupting REM sleep. After regular use, rebound insomnia may occur when discontinuing clonazepam.

- Benzodiazepines may cause or worsen depression.

Occasional

- Dysphoria

- Induction of seizures or increased frequency of seizures

- Personality changes

- Behavioural disturbances

- Ataxia

Rare

- Suicide through disinhibition

- Psychosis

- Incontinence

- Liver damage

- Paradoxical behavioural disinhibition (most frequently in children, the elderly, and in persons with developmental disabilities)

- Rage

- Excitement

- Impulsivity

The long-term effects of clonazepam can include depression, disinhibition, and sexual dysfunction.

Drowsiness

Clonazepam, like other benzodiazepines, may impair a person's ability to drive or operate machinery. The central nervous system depressing effects of the drug can be intensified by alcohol consumption, and therefore alcohol should be avoided while taking this medication. Benzodiazepines have been shown to cause dependence. Patients dependent on clonazepam should be slowly titrated off under the supervision of a qualified healthcare professional to reduce the intensity of withdrawal or rebound symptoms.

- Anxiety

- Irritability

- Insomnia

- Tremors

- Headaches

- Stomach pain

- Nausea

- Hallucinations

- Suicidal thoughts or urges

- Depression

- Fatigue

- Dizziness

- Sweating

- Confusion

- Potential to exacerbate existing panic disorder upon discontinuation

- Seizures similar to delirium tremens (with long-term use of excessive doses)

Benzodiazepines such as clonazepam can be very effective in controlling status epilepticus, but, when used for longer periods of time, some potentially serious side-effects may develop, such as interference with cognitive functions and behavior. Many individuals treated on a long-term basis develop a dependence. Physiological dependence was demonstrated by flumazenil-precipitated withdrawal. Use of alcohol or other CNS depressants while taking clonazepam greatly intensifies the effects (and side effects) of the drug.

A recurrence of symptoms of the underlying disease should be separated from withdrawal symptoms.

Tolerance and withdrawal

Like all benzodiazepines, clonazepam is a GABA-positive allosteric modulator. One-third of individuals treated with benzodiazepines for longer than four weeks develop a dependence on the drug and experience a withdrawal syndrome upon dose reduction. High dosage and long-term use increase the risk and severity of dependence and withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal seizures and psychosis can occur in severe cases of withdrawal, and anxiety and insomnia can occur in less severe cases of withdrawal. A gradual reduction in dosage reduces the severity of the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. Due to the risks of tolerance and withdrawal seizures, clonazepam is generally not recommended for the long-term management of epilepsies. Increasing the dose can overcome the effects of tolerance, but tolerance to the higher dose may occur and adverse effects may intensify. The mechanism of tolerance includes receptor desensitization, down regulation, receptor decoupling, and alterations in subunit composition and in gene transcription coding.

Tolerance to the anticonvulsant effects of clonazepam occurs in both animals and humans. In humans, tolerance to the anticonvulsant effects of clonazepam occurs frequently. Chronic use of benzodiazepines can lead to the development of tolerance with a decrease of benzodiazepine binding sites. The degree of tolerance is more pronounced with clonazepam than with chlordiazepoxide. In general, short-term therapy is more effective than long-term therapy with clonazepam for the treatment of epilepsy. Many studies have found that tolerance develops to the anticonvulsant properties of clonazepam with chronic use, which limits its long-term effectiveness as an anticonvulsant.

Abrupt or over-rapid withdrawal from clonazepam may result in the development of the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome, causing psychosis characterised by dysphoric manifestations, irritability, aggressiveness, anxiety, and hallucinations. Sudden withdrawal may also induce the potentially life-threatening condition, status epilepticus. Anti-epileptic drugs, benzodiazepines such as clonazepam in particular, should be reduced in dose slowly and gradually when discontinuing the drug to mitigate withdrawal effects. Carbamazepine has been tested in the treatment of clonazepam withdrawal but was found to be ineffective in preventing clonazepam withdrawal-induced status epilepticus from occurring.

Overdose

Excess doses may result in:

- Difficulty staying awake

- Mental confusion

- Nausea

- Impaired motor functions

- Impaired reflexes

- Impaired coordination

- Impaired balance

- Dizziness

- Respiratory depression

- Low blood pressure

- Coma

Coma can be cyclic, with the individual alternating from a comatose state to a hyper-alert state of consciousness, which occurred in a four-year-old boy who suffered an overdose of clonazepam. The combination of clonazepam and certain barbiturates (for example, amobarbital), at prescribed doses has resulted in a synergistic potentiation of the effects of each drug, leading to serious respiratory depression.

Overdose symptoms may include extreme drowsiness, confusion, muscle weakness, and fainting.

Detection in biological fluids

Clonazepam and 7-aminoclonazepam may be quantified in plasma, serum, or whole blood in order to monitor compliance in those receiving the drug therapeutically. Results from such tests can be used to confirm the diagnosis in potential poisoning victims or to assist in the forensic investigation in a case of fatal overdosage. Both the parent drug and 7-aminoclonazepam are unstable in biofluids, and therefore specimens should be preserved with sodium fluoride, stored at the lowest possible temperature and analyzed quickly to minimize losses.

Special precautions

The elderly metabolize benzodiazepines more slowly than younger people and are also more sensitive to the effects of benzodiazepines, even at similar blood plasma levels. Doses for the elderly are recommended to be about half of that given to younger adults and are to be administered for no longer than two weeks. Long-acting benzodiazepines such as clonazepam are not generally recommended for the elderly due to the risk of drug accumulation.

The elderly are especially susceptible to increased risk of harm from motor impairments and drug accumulation side effects. Benzodiazepines also require special precaution if used by individuals that may be pregnant, alcohol- or drug-dependent, or may have comorbid psychiatric disorders. Clonazepam is generally not recommended for use in elderly people for insomnia due to its high potency relative to other benzodiazepines.

Clonazepam is not recommended for use in those under 18. Use in very young children may be especially hazardous. Of anticonvulsant drugs, behavioural disturbances occur most frequently with clonazepam and phenobarbital.

Doses higher than 0.5–1 mg per day are associated with significant sedation.

Clonazepam may aggravate hepatic porphyria.

Clonazepam is not recommended for patients with chronic schizophrenia. A 1982 double-blinded, placebo-controlled study found clonazepam increases violent behavior in individuals with chronic schizophrenia.

Clonazepam has similar effectiveness to other benzodiazepines at often a lower dose.

Interactions

Clonazepam decreases the levels of carbamazepine, and, likewise, clonazepam's level is reduced by carbamazepine. Azole antifungals, such as ketoconazole, may inhibit the metabolism of clonazepam. Clonazepam may affect levels of phenytoin (diphenylhydantoin). In turn, Phenytoin may lower clonazepam plasma levels by increasing the speed of clonazepam clearance by approximately 50% and decreasing its half-life by 31%. Clonazepam increases the levels of primidone and phenobarbital.

Combined use of clonazepam with certain antidepressants, anticonvulsants (such as phenobarbital, phenytoin, and carbamazepine), sedative antihistamines, opiates, and antipsychotics, nonbenzodiazepines (such as zolpidem), and alcohol may result in enhanced sedative effects.

Pregnancy

There is some medical evidence of various malformations, (for example, cardiac or facial deformations when used in early pregnancy); however, the data is not conclusive. The data are also inconclusive on whether benzodiazepines such as clonazepam cause developmental deficits or decreases in IQ in the developing fetus when taken by the mother during pregnancy. Clonazepam, when used late in pregnancy, may result in the development of a severe benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome in the neonate. Withdrawal symptoms from benzodiazepines in the neonate may include hypotonia, apnoeic spells, cyanosis, and impaired metabolic responses to cold stress.

The safety profile of clonazepam during pregnancy is less clear than that of other benzodiazepines, and if benzodiazepines are indicated during pregnancy, chlordiazepoxide and diazepam may be a safer choice. The use of clonazepam during pregnancy should only occur if the clinical benefits are believed to outweigh the clinical risks to the fetus. Caution is also required if clonazepam is used during breastfeeding. Possible adverse effects of use of benzodiazepines such as clonazepam during pregnancy include: miscarriage, malformation, intrauterine growth retardation, functional deficits, carcinogenesis, and mutagenesis. Neonatal withdrawal syndrome associated with benzodiazepines include hypertonia, hyperreflexia, restlessness, irritability, abnormal sleep patterns, inconsolable crying, tremors, or jerking of the extremities, bradycardia, cyanosis, suckling difficulties, apnea, risk of aspiration of feeds, diarrhea and vomiting, and growth retardation. This syndrome can develop between three days to three weeks after birth and can have a duration of up to several months. The pathway by which clonazepam is metabolized is usually impaired in newborns. If clonazepam is used during pregnancy or breastfeeding, it is recommended that serum levels of clonazepam are monitored and that signs of central nervous system depression and apnea are also checked for. In many cases, non-pharmacological treatments, such as relaxation therapy, psychotherapy, and avoidance of caffeine, can be an effective and safer alternative to the use of benzodiazepines for anxiety in pregnant women.

Mechanism of action

Clonazepam enhances the activity of the inhibitory neurotransmitter Gamma-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the central nervous system to give its anticonvulsant, skeletal muscle relaxant, and anxiolytic effects. It acts by binding to the benzodiazepine site of the GABA receptors, which enhances the electric effect of GABA binding on neurons, resulting in an increased influx of chloride ions into the neurons. This further results in an inhibition of synaptic transmission across the central nervous system.

Benzodiazepines do not have any effect on the levels of GABA in the brain. Clonazepam has no effect on GABA levels and has no effect on gamma-aminobutyric acid transaminase. Clonazepam does, however, affect glutamate decarboxylase activity. It differs from other anticonvulsant drugs it was compared to in a study.

Clonazepam's primary mechanism of action is the modulation of GABA function in the brain, by the benzodiazepine receptor, located on GABAA receptors, which, in turn, leads to enhanced GABAergic inhibition of neuronal firing. Benzodiazepines do not replace GABA, but instead enhance the effect of GABA at the GABAA receptor by increasing the opening frequency of chloride ion channels, which leads to an increase in GABA's inhibitory effects and resultant central nervous system depression. In addition, clonazepam decreases the utilization of 5-HT (serotonin) by neurons and has been shown to bind tightly to central-type benzodiazepine receptors. Because clonazepam is effective in low milligram doses (0.5 mg clonazepam = 10 mg diazepam), it is said to be among the class of "highly potent" benzodiazepines. The anticonvulsant properties of benzodiazepines are due to the enhancement of synaptic GABA responses, and the inhibition of sustained, high-frequency repetitive firing.

Benzodiazepines, including clonazepam, bind to mouse glial cell membranes with high affinity. Clonazepam decreases release of acetylcholine in the feline brain and decreases prolactin release in rats. Benzodiazepines inhibit cold-induced thyroid-stimulating hormone (also known as TSH or thyrotropin) release. Benzodiazepines acted via micromolar benzodiazepine binding sites as Ca2+ channel blockers and significantly inhibit depolarization-sensitive calcium uptake in experimentation on rat brain cell components. This has been conjectured as a mechanism for high-dose effects on seizures in the study.

Clonazepam is a 2'-chlorinated derivative of nitrazepam, which increases its potency due to electron-attracting effect of the halogen in the ortho-position.

Pharmacokinetics

Clonazepam is lipid-soluble, rapidly crosses the blood–brain barrier, and penetrates the placenta. It is extensively metabolised into pharmacologically inactive metabolites, with only 2% of the unchanged drug excreted in the urine. Clonazepam is metabolized extensively via nitroreduction by cytochrome P450 enzymes, including CYP3A4. Erythromycin, clarithromycin, ritonavir, itraconazole, ketoconazole, nefazodone, cimetidine, and grapefruit juice are inhibitors of CYP3A4 and can affect the metabolism of benzodiazepines. It has an elimination half-life of 19–60 hours. Peak blood concentrations of 6.5–13.5 ng/mL were usually reached within 1–2 hours following a single 2 mg oral dose of micronized clonazepam in healthy adults. In some individuals, however, peak blood concentrations were reached at 4–8 hours.

Clonazepam passes rapidly into the central nervous system, with levels in the brain corresponding with levels of unbound clonazepam in the blood serum. Clonazepam plasma levels are very unreliable amongst patients. Plasma levels of clonazepam can vary as much as tenfold between different patients.

Clonazepam has plasma protein binding of 85%. Clonazepam passes through the blood–brain barrier easily, with blood and brain levels corresponding equally with each other. The metabolites of clonazepam include 7-aminoclonazepam, 7-acetaminoclonazepam and 3-hydroxy clonazepam. These metabolites are excreted by the kidney.

It is effective for 6–8 hours in children, and 6–12 in adults.

Society and culture

Recreational use

A 2006 US government study of hospital emergency department (ED) visits found that sedative-hypnotics were the most frequently implicated pharmaceutical drug in visits, with benzodiazepines accounting for the majority of these. Clonazepam was the second most frequently implicated benzodiazepine in ED visits. Alcohol alone was responsible for over twice as many ED visits as clonazepam in the same study. The study examined the number of times the non-medical use of certain drugs was implicated in an ED visit. The criteria for non-medical use in this study were purposefully broad, and include, for example, drug abuse, accidental or intentional overdose, or adverse reactions resulting from legitimate use of the medication.

Formulations

Clonazepam was approved in the United States as a generic drug in 1997 and is now manufactured and marketed by several companies.

Clonazepam is available as tablets and orally disintegrating tablets (wafers) an oral solution (drops), and as a solution for injection or intravenous infusion.

Brand names

It is marketed under the trade name Rivotril by Roche in Argentina, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, China, Mexico, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Peru, Romania, Serbia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Turkey, and the United States; Emcloz, Linotril and Clonotril in India and other parts of Europe; under the name Riklona in Indonesia and Malaysia; and under the trade name Klonopin by Roche in the United States. Other names, such as Clonoten, Ravotril, Rivotril, Iktorivil, Clonex, Paxam, Petril, Naze, Zilepam and Kriadex, are known throughout the world.