Speciesism (/ˈspiːʃiːˌzɪzəm, -siːˌzɪz-/) is a term used in philosophy regarding the treatment of individuals of different species. The term has several different definitions within the relevant literature. A common element of most definitions is that speciesism involves treating members of one species as morally more important than members of other species in the context of their similar interests. Some sources specifically define speciesism as discrimination or unjustified treatment based on an individual's species membership, while other sources define it as differential treatment without regard to whether the treatment is justified or not. Richard Ryder, who coined the term, defined it as "a prejudice or attitude of bias in favour of the interests of members of one's own species and against those of members of other species." Speciesism results in the belief that humans have the right to use non-human animals, which scholars say is so pervasive in the modern society. Studies increasingly suggest that people who support animal exploitation also tend to endorse racist, sexist, and other prejudicial views, which furthers the beliefs in human supremacy and group dominance to justify systems of inequality and oppression.

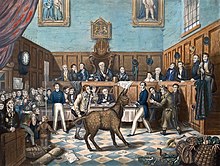

Philosophers argue that there is a normative relationship between speciesism and other prejudices such as racism, sexism, homophobia and so forth. As a term, speciesism first appeared during a protest against animal experimentation in 1970. Philosophers and animal rights advocates state that speciesism plays a role in the animal–industrial complex, including in the practice of factory farming, animal slaughter, blood sports (such as bullfighting and rodeos), the taking of animals' fur and skin, and experimentation on animals, as well as the refusal to help animals suffering in the wild due to natural processes and the categorization of certain animals as invasive, then killing them based on that classification. They argue speciesism is a form of discrimination that constitutes a violation of the Golden Rule because it involves treating other beings differently to how they would want to be treated because of the species that they belong to.

Notable proponents of the concept include Peter Singer, Oscar Horta, Steven M. Wise, Gary L. Francione, Melanie Joy, David Nibert, Steven Best and Ingrid Newkirk. Among academics, the ethics, morality, and concept of speciesism has been the subject of substantial philosophical debate.

Preceding ideas

Buffon, a French naturalist, writing in Histoire Naturelle, published in 1753, questioned whether it could be doubted that animals "whose organization is similar to ours, must experience similar sensations" and that "those sensations must be proportioned to the activity and perfection of their senses". Despite these assertions, he insisted that there exists a gap between humans and other animals. In the poem "Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne", Voltaire described a kinship between sentient beings, humans and other animals included, stating: "All sentient things, born by the same stern law, / Suffer like me, and like me also die."

In Moral Inquiries on the Situation of Man and of Brutes, published in 1824, the English writer and advocate for animal rights Lewis Gompertz, argued for egalitarianism and detailed how it could be applied to nonhuman animals. He asserted that the feelings and sensations experienced by humans and other animals are highly similar, stating: "Things which affect us, generally seem to affect them in the same way; and at least the following sensations and passions are common to both, viz. hunger, desire, emulation, love of liberty, playfulness, fear, shame, anger, and many other affections". He also argued that humans and other animals share many physiological characteristics and that this implied "similitude of sensation". Gompertz was critical of the human use of nonhuman animals, arguing that they are used "without the slightest regard to their feelings, their wants, and their desires".

English naturalist Charles Darwin, writing in his notebook in 1838, asserted that man thinks of himself as a masterpiece produced by a deity, but that he thought it "truer to consider him created from animals." In his 1871 book The Descent of Man, Darwin argued that:

There is no fundamental difference between man and the higher mammals in their mental faculties ... [t]he difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, certainly is one of degree and not of kind. We have seen that the senses and intuitions, the various emotions and faculties, such as love, memory, attention, curiosity, imitation, reason, etc., of which man boasts, may be found in an incipient, or even sometimes in a well-developed condition, in the lower animals.

English writer and animal rights advocate Henry S. Salt in his 1892 book Animals' Rights, argued that for humans to do justice to other animals, that they must look beyond the conception of a "great gulf" between them, claiming instead that we should recognize the "common bond of humanity that unites all living beings in one universal brotherhood".

Edward Payson Evans, an American scholar and animal rights advocate, in Evolutional Ethics and Animal Psychology, published in 1898, was critical of anthropocentric psychology and ethics, which he argued "treat man as a being essentially different and inseparably set apart from all other sentient creatures, to which he is bound by no ties of mental affinity or moral obligation". Evans argued that Darwin's theory of evolution implied moral obligations towards enslaved humans and nonhuman animals, asserting that these obligations not only implied that cruelty to slaves must be mitigated and that slavery be abolished, but also that nonhuman animals need more than just kind treatment; they require rights to protect them and that would be enforced if violated. Evans also contended that widespread recognition of the kinship between humans and even the most insignificant sentient beings would necessarily mean that it would be impossible to neglect or mistreat them.

Writing in 1895, the American zoologist, philosopher and animal rights advocate J. Howard Moore described vegetarianism as the ethical conclusion of the evolutionary kinship of all creatures, calling it the "expansion of ethics to suit the biological revelations of Charles Darwin". He went on to argue that ethics still relied on a "pre-Darwinian delusion" that all nonhuman animals and the world were created specifically for humans. In his 1899 book Better World Philosophy, Moore contended that human ethics is in an "anthropocentric stage of evolution", having developed "from individual to tribe, and from tribe to race, and from race to sex, and from sex to species, until to-day the ethical conception of many minds includes, with greater or less vividness and sincerity, all sexes, colors, and conditions of men." He argued that the next stage of ethical evolution was "zoocentricism", the ethical consideration of the "entire sentient universe".

In his 1906 book The Universal Kinship, Moore asserted that a "provincialist" attitude towards other animals leads humans to mistreat them and compared the denial of an ethical connection between humans and animals to the "denial of ethical relations by a tribe, people, or race of human beings to the rest of the human world." He went on to criticize the anthropocentric perspective of humans, who "think of our acts toward non-human peoples ... entirely from the human point of view. We never take the time to put ourselves in the places of our victims." In his conclusion, Moore argued that the Golden Rule should be applied to all sentient beings, stating "do as you would be done by—and not to the dark man and the white woman alone, but to the sorrel horse and the gray squirrel as well; not to creatures of your own anatomy only, but to all creatures."

Etymology

The term speciesism, and the argument that it is a prejudice, first appeared in 1970 in a privately printed pamphlet written by British psychologist Richard D. Ryder. Ryder was a member of a group of academics in Oxford, England, the nascent animal rights community, now known as the Oxford Group. One of the group's activities was distributing pamphlets about areas of concern; the pamphlet titled "Speciesism" was written to protest against animal experimentation. The term was intended by its proponents to create a rhetorical and categorical link to racism and sexism.

Ryder stated in the pamphlet that "[s]ince Darwin, scientists have agreed that there is no 'magical' essential difference between humans and other animals, biologically-speaking. Why then do we make an almost total distinction morally? If all organisms are on one physical continuum, then we should also be on the same moral continuum." He wrote that, at that time in the United Kingdom, 5,000,000 animals were being used each year in experiments, and that attempting to gain benefits for our own species through the mistreatment of others was "just 'speciesism' and as such it is a selfish emotional argument rather than a reasoned one". Ryder used the term again in an essay, "Experiments on Animals", in Animals, Men and Morals (1971), a collection of essays on animal rights edited by philosophy graduate students Stanley and Roslind Godlovitch and John Harris, who were also members of the Oxford Group. Ryder wrote:

In as much as both "race" and "species" are vague terms used in the classification of living creatures according, largely, to physical appearance, an analogy can be made between them. Discrimination on grounds of race, although most universally condoned two centuries ago, is now widely condemned. Similarly, it may come to pass that enlightened minds may one day abhor "speciesism" as much as they now detest "racism." The illogicality in both forms of prejudice is of an identical sort. If it is accepted as morally wrong to deliberately inflict suffering upon innocent human creatures, then it is only logical to also regard it as wrong to inflict suffering on innocent individuals of other species. ... The time has come to act upon this logic.

Spread of the idea

The term was popularized by the Australian philosopher Peter Singer in his book Animal Liberation (1975). Singer had known Ryder from his own time as a graduate philosophy student at Oxford. He credited Ryder with having coined the term and used it in the title of his book's fifth chapter: "Man's Dominion ... a short history of speciesism", defining it as "a prejudice or attitude of bias in favour of the interests of members of one's own species and against those of members of other species":

Racists violate the principle of equality by giving greater weight to the interests of members of their own race when there is a clash between their interests and the interests of those of another race. Sexists violate the principle of equality by favouring the interests of their own sex. Similarly, speciesists allow the interests of their own species to override the greater interests of members of other species. The pattern is identical in each case.

Singer stated from a preference-utilitarian perspective, writing that speciesism violates the principle of equal consideration of interests, the idea based on Jeremy Bentham's principle: "each to count for one, and none for more than one." Singer stated that, although there may be differences between humans and nonhumans, they share the capacity to suffer, and we must give equal consideration to that suffering. Any position that allows similar cases to be treated in a dissimilar fashion fails to qualify as an acceptable moral theory. The term caught on; Singer wrote that it was an awkward word but that he could not think of a better one. It became an entry in the Oxford English Dictionary in 1985, defined as "discrimination against or exploitation of animal species by human beings, based on an assumption of mankind's superiority." In 1994 the Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy offered a wider definition: "By analogy with racism and sexism, the improper stance of refusing respect to the lives, dignity, or needs of animals of other than the human species."

Anti-speciesism movement

The French-language journal Cahiers antispécistes ("Antispeciesist notebooks") was founded in 1991, by David Olivier, Yves Bonnardel and Françoise Blanchon, who were the first French activists to speak out against speciesism. The aim of the journal was to disseminate anti-speciesist ideas in France and to encourage debate on the topic of animal ethics, specifically on the difference between animal liberation and ecology. Estela Díaz and Oscar Horta assert that in Spanish-speaking countries, unlike English-speaking countries, anti-speciesism has become the dominant approach for animal advocacy. In Italy, two distinct trends have been identified in the contemporary anti-speciesist movement, the first focusing on radical counter-hegemonic positions and the second on mainstream neoliberal ones.

More recently, animal rights groups such as the Farm Animal Rights Movement and People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals have attempted to popularize the concept by promoting a World Day Against Speciesism on June 5.

Social psychology and the relationship with other prejudices

Philosophers have argued there is a normative relationship between speciesism and other prejudices such as racism, sexism, homophobia and so forth. Studies suggest speciesism involves similar psychological processes and motivations as those underlying other prejudices. In the 2019 book Why We Love and Exploit Animals, Kristof Dhont, Gordon Hodson, Ana C. Leite, and Alina Salmen reveal the psychological connections between speciesism and other prejudices such as racism and sexism. According to a study, people who score higher on speciesism also score higher on racism, sexism, and homophobia. Scholars say people supporting animal exploitation also tend to endorse racist and sexist views, furthering the beliefs in human supremacy and group dominance in order to justify systems of inequality and oppression. Studies suggests that the connection rests in the ideology of social dominance.

Psychologists have also considered examining speciesism as a specific psychological construct or attitude (as opposed to speciesism as a philosophy), which was achieved using a specifically designed Likert scale. Studies have found that speciesism is a stable construct that differs amongst personalities and correlates with other variables. For example, speciesism has been found to have a weak positive correlation with homophobia and right-wing authoritarianism, as well as slightly stronger correlations with political conservatism, racism and system justification. Moderate positive correlations were found with social dominance orientation and sexism. Social dominance orientation was theorised to be underpinning most of the correlations; controlling for social dominance orientation reduces all correlations substantially and renders many statistically insignificant. Speciesism likewise predicts levels of prosociality toward animals and behavioural food choices.

Those who state that speciesism is unfair to individuals of nonhuman species have often invoked mammals and chickens in the context of research or farming. There is not yet a clear definition or line agreed upon by a significant segment of the movement as to which species are to be treated equally with humans or in some ways additionally protected: mammals, birds, reptiles, arthropods, insects, bacteria, etc. This question is all the more complex since a study by Miralles et al. (2019) has brought to light the evolutionary component of human empathic and compassionate reactions and the influence of anthropomorphic mechanisms in our affective relationship with the living world as a whole: the more an organism is evolutionarily distant from us, the less we recognize ourselves in it and the less we are moved by its fate.

Some researchers have suggested that since speciesism could be considered, in terms of social psychology, a prejudice (defined as "any attitude, emotion, or behaviour toward members of a group, which directly or indirectly implies some negativity or antipathy toward that group"), then laypeople may be aware of a connection between it and other forms of "traditional" prejudice. Research suggests laypeople do indeed tend to infer similar personality traits and beliefs from a speciesist that they would from a racist, sexist or homophobe. However, it is not clear if there is a link between speciesism and non-traditional forms of prejudice such as negative attitudes towards the overweight or towards Christians.

Psychological studies have furthermore argued that people tend to "morally value individuals of certain species less than others even when beliefs about intelligence and sentience are accounted for."

Relationship with the animal–industrial complex

Piers Beirne considers speciesism as the ideological anchor of the intersecting networks of the animal–industrial complex, such as factory farms, vivisection, hunting and fishing, zoos and aquaria, wildlife trade, and so forth. Amy Fitzgerald and Nik Taylor argue that the animal-industrial complex is both a consequence and cause of speciesism, which according to them is a form of discrimination similar to racism or sexism. They also argue that the obfuscation of meat's animal origins is a critical part of the animal–industrial complex under capitalist and neoliberal regimes. Speciesism results in the belief that humans have the right to use non-human animals, which is so pervasive in the modern society.

Sociologist David Nibert states,

The profound cultural devaluation of other animals that permits the violence that underlies the animal industrial complex is produced by far-reaching speciesist socialization. For instance, the system of primary and secondary education under the capitalist system largely indoctrinates young people into the dominant societal beliefs and values, including a great deal of procapitalist and speciesist ideology. The devalued status of other animals is deeply ingrained; animals appear in schools merely as caged "pets," as dissection and vivisection subjects, and as lunch. On television and in movies, the unworthiness of other animals is evidenced by their virtual invisibility; when they do appear, they generally are marginalized, vilified, or objectified. Not surprisingly, these and numerous other sources of speciesism are so ideologically profound that those who raise compelling moral objections to animal oppression largely are dismissed, if not ridiculed.

Scholars argue that all kinds of animal production is rooted in speciesism, reducing animals to mere economic resources. Built on the production and slaughter of animals, the animal–industrial complex is perceived as the materialization of the institution of speciesism, with speciesism becoming "a mode of production". In his 2011 book Critical Theory and Animal Liberation, J. Sanbonmatsu argues that speciesism is not ignorance or the absence of a moral code towards animals, but is a mode of production and material system imbricated with capitalism.

Arguments in favor

Philosophical

A common theme in defending speciesism is the argument that humans have the right to exploit other species to defend their own. Philosopher Carl Cohen stated in 1986: "Speciesism is not merely plausible; it is essential for right conduct, because those who will not make the morally relevant distinctions among species are almost certain, in consequence, to misapprehend their true obligations." Cohen writes that racism and sexism are wrong because there are no relevant differences between the sexes or races. Between people and animals, he states, there are significant differences; his view is that animals do not qualify for Kantian personhood, and as such have no rights.

Nel Noddings, the American feminist, has criticized Singer's concept of speciesism for being simplistic, and for failing to take into account the context of species preference, as concepts of racism and sexism have taken into account the context of discrimination against humans. Peter Staudenmaier has stated that comparisons between speciesism and racism or sexism are trivializing:

The central analogy to the civil rights movement and the women's movement is trivializing and ahistorical. Both of those social movements were initiated and driven by members of the dispossessed and excluded groups themselves, not by benevolent men or white people acting on their behalf. Both movements were built precisely around the idea of reclaiming and reasserting a shared humanity in the face of a society that had deprived it and denied it. No civil rights activist or feminist ever argued, "We're sentient beings too!" They argued, "We're fully human too!" Animal liberation doctrine, far from extending this humanist impulse, directly undermines it.

A similar argument was made by Bernard Williams, who observed that a difference between speciesism versus racism and sexism is that racists and sexists deny any input from those of a different race or sex when it comes to questioning how they should be treated. Conversely, when it comes to how animals should be treated by humans, Williams observed that it is only possible for humans to discuss that question. Williams observed that being a human being is often used as an argument against discrimination on the grounds of race or sex, whereas racism and sexism are seldom deployed to counter discrimination.

Williams also stated in favour of speciesism (which he termed 'humanism'), arguing that "Why are fancy properties which are grouped under the label of personhood "morally relevant" to issues of destroying a certain kind of animal, while the property of being a human being is not?" Williams states that to respond by arguing that it is because these are properties considered valuable by human beings does not undermine speciesism as humans also consider human beings to be valuable, thus justifying speciesism. Williams then states that the only way to resolve this would be by arguing that these properties are "simply better" but in that case, one would need to justify why these properties are better if not because of human attachment to them. Christopher Grau supported Williams, arguing that if one used properties like rationality, sentience and moral agency as criteria for moral status as an alternative to species-based moral status, then it would need to be shown why these particular properties are to be used instead of others; there must be something that gives them special status. Grau states that to claim these are simply better properties would require the existence of an impartial observer, an "enchanted picture of the universe", to state them to be so. Thus Grau states that such properties have no greater justification as criteria for moral status than being a member of a species does. Grau also states that even if such an impartial perspective existed, it still would not necessarily be against speciesism, since it is entirely possible that there could be reasons given by an impartial observer for humans to care about humanity. Grau then further observes that if an impartial observer existed and valued only minimalizing suffering, it would likely be overcome with horror at the suffering of all individuals and would rather have humanity annihilate the planet than allow it to continue. Grau thus concludes that those endorsing the idea of deriving values from an impartial observer do not seem to have seriously considered the conclusions of such an idea.

Objectivist philosopher Leonard Peikoff stated: "By its nature and throughout the animal kingdom, life survives by feeding on life. To demand that man defer to the 'rights' of other species is to deprive man himself of the right to life. This is 'other-ism,' i.e. altruism, gone mad."

Douglas Maclean agreed that Singer raised important questions and challenges, particularly with his argument from marginal cases. However, Maclean questioned if different species can be fitted with human morality, observing that animals were generally held exempt from morality; Maclean notes that most people would try to stop a man kidnapping and killing a woman but would regard a hawk capturing and killing a marmot with awe and criticise anyone who tried to intervene. Maclean thus suggests that morality only makes sense under human relations, with the further one gets from it the less it can be applied.

The British philosopher, Roger Scruton, regards the emergence of the animal rights and anti-speciesism movement as "the strangest cultural shift within the liberal worldview", because the idea of rights and responsibilities is, he states, distinctive to the human condition, and it makes no sense to spread them beyond our own species. Scruton argues that if animals have rights, then they also have duties, which animals would routinely violate, such as by breaking laws or killing other animals. He accuses anti-speciesism advocates of "pre-scientific" anthropomorphism, attributing traits to animals that are, he says, Beatrix Potter-like, where "only man is vile." It is, he states, a fantasy, a world of escape.

Thomas Wells states that Singer's call for ending animal suffering would justify simply exterminating every animal on the planet in order to prevent the numerous ways in which they suffer, as they could no longer feel any pain. Wells also stated that by focusing on the suffering humans inflict on animals and ignoring suffering animals inflict upon themselves or that inflicted by nature, Singer is creating a hierarchy where some suffering is more important than others, despite claiming to be committed to equality of suffering. Wells also states that the capacity to suffer, Singer's criteria for moral status, is one of degree rather than absolute categories; Wells observes that Singer denies moral status to plants on the grounds they cannot subjectively feel anything (even though they react to stimuli), yet Wells alleges there is no indication that nonhuman animals feel pain and suffering the way humans do.

Robert Nozick notes that if species membership is irrelevant, then this would mean that endangered animals have no special claim.

Religious

The Rev. John Tuohey, founder of the Providence Center for Health Care Ethics, writes that the logic behind the anti-speciesism critique is flawed, and that, although the animal rights movement in the United States has been influential in slowing animal experimentation, and in some cases halting particular studies, no one has offered a compelling argument for species equality.

Some proponents of speciesism believe that animals exist so that humans may make use of them. They state that this special status conveys special rights, such as the right to life, and also unique responsibilities, such as stewardship of the environment. This belief in human exceptionalism is often rooted in the Abrahamic religions, such as the Book of Genesis 1:26: "Then God said, 'Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness, so that they may rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky, over the livestock and all the wild animals, and over all the creatures that move along the ground.'" Some Christian theologists assert that dominion refers to stewardship, not ownership. Jesus Christ taught that a person is worth more than many sparrows. But the Imago Dei may be personhood itself, although we humans have only achieved efficiencies in educating and otherwise acculturating humans. Proverbs 12:10 says that "Whoever is righteous has regard for the life of his beast, but the mercy of the wicked is cruel."

Arguments against

Moral community, argument from marginal cases

Paola Cavalieri writes that the current humanist paradigm is that only human beings are members of the moral community and that all are worthy of equal protection. Species membership, she writes, is ipso facto moral membership. The paradigm has an inclusive side (all human beings deserve equal protection) and an exclusive one (only human beings have that status).

She writes that it is not only philosophers who have difficulty with this concept. Richard Rorty (1931–2007) stated that most human beings – those outside what he called our "Eurocentric human rights culture" – are unable to understand why membership of a species would in itself be sufficient for inclusion in the moral community: "Most people live in a world in which it would be just too risky – indeed, it would often be insanely dangerous – to let one's sense of moral community stretch beyond one's family, clan or tribe." Rorty wrote:

Such people are morally offended by the suggestion that they should treat someone who is not kin as if he were a brother, or a nigger as if he were white, or a queer as if he were normal, or an infidel as if she were a believer. They are offended by the suggestion that they treat people whom they do not think of as human as if they were human. When utilitarians tell them that all pleasures and pains felt by members of our biological species are equally relevant to moral deliberation, or when Kantians tell them that the ability to engage in such deliberation is sufficient for membership in the moral community, they are incredulous. They rejoin that these philosophers seem oblivious to blatantly obvious moral distinctions, distinctions that any decent person will draw.

Much of humanity is similarly offended by the suggestion that the moral community be extended to nonhumans. Nonhumans do possess some moral status in many societies, but it generally extends only to protection against what Cavalieri calls "wanton cruelty". Anti-speciesists state that the extension of moral membership to all humanity, regardless of individual properties such as intelligence, while denying it to nonhumans, also regardless of individual properties, is internally inconsistent. According to the argument from marginal cases, if infants, the senile, the comatose, and the cognitively disabled (marginal-case human beings) have a certain moral status, then nonhuman animals must be awarded that status too since there is no morally relevant ability that the marginal-case humans have that nonhumans lack.

American legal scholar Steven M. Wise states that speciesism is a bias as arbitrary as any other. He cites the philosopher R.G. Frey (1941–2012), a leading animal rights critic, who wrote in 1983 that, if forced to choose between abandoning experiments on animals and allowing experiments on "marginal-case" humans, he would choose the latter, "not because I begin a monster and end up choosing the monstrous, but because I cannot think of anything at all compelling that cedes all human life of any quality greater value than animal life of any quality."

"Discontinuous mind"

Richard Dawkins, the evolutionary biologist, wrote against speciesism in The Blind Watchmaker (1986), The Great Ape Project (1993), and The God Delusion (2006), elucidating the connection with evolutionary theory. He compares former racist attitudes and assumptions to their present-day speciesist counterparts. In the chapter "The one true tree of life" in The Blind Watchmaker, he states that it is not only zoological taxonomy that is saved from awkward ambiguity by the extinction of intermediate forms but also human ethics and law. Dawkins states that what he calls the "discontinuous mind" is ubiquitous, dividing the world into units that reflect nothing but our use of language, and animals into discontinuous species:

The director of a zoo is entitled to "put down" a chimpanzee that is surplus to requirements, while any suggestion that he might "put down" a redundant keeper or ticket-seller would be greeted with howls of incredulous outrage. The chimpanzee is the property of the zoo. Humans are nowadays not supposed to be anybody's property, yet the rationale for discriminating against chimpanzees is seldom spelled out, and I doubt if there is a defensible rationale at all. Such is the breathtaking speciesism of our Christian-inspired attitudes, the abortion of a single human zygote (most of them are destined to be spontaneously aborted anyway) can arouse more moral solicitude and righteous indignation than the vivisection of any number of intelligent adult chimpanzees! ... The only reason we can be comfortable with such a double standard is that the intermediates between humans and chimps are all dead.

Dawkins elaborated in a discussion with Singer at The Center for Inquiry in 2007 when asked whether he continues to eat meat: "It's a little bit like the position which many people would have held a couple of hundred years ago over slavery. Where lots of people felt morally uneasy about slavery but went along with it because the whole economy of the South depended upon slavery."

Centrality of consciousness

"Libertarian extension" is the idea that the intrinsic value of nature can be extended beyond sentient beings. This seeks to apply the principle of individual rights not only to all animals but also to objects without a nervous system such as trees, plants, and rocks. Ryder rejects this argument, writing that "value cannot exist in the absence of consciousness or potential consciousness. Thus, rocks and rivers and houses have no interests and no rights of their own. This does not mean, of course, that they are not of value to us, and to many other [beings who experience pain], including those who need them as habitats and who would suffer without them."

Comparisons to the Holocaust

David Sztybel states in his paper, "Can the Treatment of Animals Be Compared to the Holocaust?" (2006), that the racism of the Nazis is comparable to the speciesism inherent in eating meat or using animal by-products, particularly those produced on factory farms. Y. Michael Barilan, an Israeli physician, states that speciesism is not the same thing as Nazi racism, because the latter extolled the abuser and condemned the weaker and the abused. He describes speciesism as the recognition of rights on the basis of group membership, rather than solely on the basis of moral considerations.

Law and policy

Law

The first major statute addressing animal protection in the United States, titled "An Act for the More Effectual Prevention of Cruelty to Animals", was enacted in 1867. It provided the right to incriminate and enforce protection with regards to animal cruelty. The act, which has since been revised to suit modern cases state by state, originally addressed such things as animal neglect, abandonment, torture, fighting, transport, impound standards and licensing standards. Although an animal rights movement had already started as early as the late 1800s, some of the laws that would shape the way animals would be treated as industry grew, were enacted around the same time that Richard Ryder was bringing the notion of Speciesism to the conversation. Legislation was being proposed and passed in the U.S. that would reshape animal welfare in industry and science. Bills such as Humane Slaughter Act, which was created to alleviate some of the suffering felt by livestock during slaughter, was passed in 1958. Later the Animal Welfare Act of 1966, passed by the 89th United States Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, was designed to put much stricter regulations and supervisions on the handling of animals used in laboratory experimentation and exhibition but has since been amended and expanded. These groundbreaking laws foreshadowed and influenced the shifting attitudes toward nonhuman animals in their rights to humane treatment which Richard D. Ryder and Peter Singer would later popularize in the 1970s and 1980s.

Great ape personhood

Great ape personhood is the idea that the attributes of nonhuman great apes are such that their sentience and personhood should be recognized by the law, rather than simply protecting them as a group under animal cruelty legislation. Awarding personhood to nonhuman primates would require that their individual interests be taken into account.