| Standard Chinese | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Mainland China, Taiwan, Singapore |

Native speakers | Has begun acquiring native speakers (as of 1988) L1 & L2 speakers: 70% of China, 7% fluent (2014) |

Sino-Tibetan

| |

Early form | |

| Traditional Chinese Simplified Chinese Mainland Chinese Braille Taiwanese Braille Two-Cell Chinese Braille | |

| Signed Chinese | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Regulated by | National Language Regulating Committee (China) National Languages Committee (Taiwan) Promote Mandarin Council (Singapore) Chinese Language Standardisation Council (Malaysia) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| ISO 639-6 | goyu (Guoyu) |

| Glottolog | None |

| Common name in mainland China | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 普通話 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 普通话 | ||

| Literal meaning | Common speech | ||

| |||

| Common name in Taiwan | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 國語 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 国语 | ||

| Literal meaning | National language | ||

| |||

| Common name in Singapore and Southeast Asia | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 華語 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 华语 | ||

| Literal meaning | Chinese language | ||

|

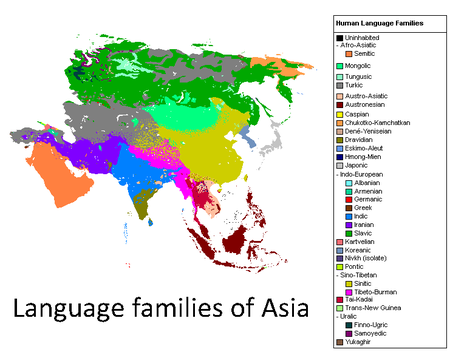

Standard Chinese (simplified Chinese: 普通话; traditional Chinese: 普通話; pinyin: pǔtōnghuà), in linguistics known as Standard Northern Mandarin, Standard Beijing Mandarin or simply Mandarin, is a dialect of Mandarin that emerged as the lingua franca among the speakers of various Mandarin and other varieties of Chinese (Hokkien, Cantonese and beyond). Standard Mandarin is designated as one of the major languages in the United Nations, mainland China, Singapore, and Taiwan.

Like other Sinitic languages, Standard Mandarin is a tonal language with topic-prominent organization and subject–verb–object word order. It has more initial consonants but fewer vowels, final consonants and tones than southern varieties. Standard Mandarin is an analytic language, though with many compound words.

Naming

In English

Among linguists, it is known as Standard Northern Mandarin or Standard Beijing Mandarin. Colloquially, it is imprecisely referred simply as Mandarin, though "Mandarin" may refer to the standard dialect, the Mandarin dialect group as a whole, or its historic standard such as Imperial Mandarin. The name "Modern Standard Mandarin" is used to distinguish its historic standard.

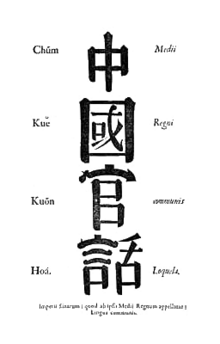

The term "Mandarin" is a translation of Guānhuà (官話; 官话, literally "bureaucrats' speech"), which referred to Imperial Mandarin.

In Chinese

Guoyu and Putonghua

The term Guóyǔ (國語; 国语) or the "national language", had previously been used by the Manchu-ruled Qing dynasty of China to refer to the Manchurian language. As early as 1655, in the Memoir of Qing Dynasty, Volume: Emperor Nurhaci (清太祖實錄), it writes: "(In 1631) as Manchu ministers do not comprehend the Han language, each ministry shall create a new position to be filled up by Han official who can comprehend the national language." In 1909, the Qing education ministry officially proclaimed Imperial Mandarin to be the new "national language".

The term Pǔtōnghuà (普通話; 普通话) or the "common tongue", is dated back to 1906 in writings by Zhu Wenxiong to differentiate Modern Standard Mandarin from classical Chinese and other varieties of Chinese.

Conceptually, the national language contrasts with the common tongue by emphasizing the aspect of legal authority.

Usage concern in a multi-ethnic nation

"The Countrywide Spoken and Written Language" (國家通用語言文字) has been increasingly used by the PRC government since the 2010s, mostly targeting students of ethnic minorities. The term has a strong connotation of being a "legal requirement" as it derives its name from the title of a law passed in 2000. The 2000 law defines Pǔtōnghuà as the one and only "Countrywide Spoken and Written Language".

Usage of the term Pǔtōnghuà (common tongue) deliberately avoided calling the language "the national language," in order to mitigate the impression of forcing ethnic minorities to adopt the language of the dominant ethnic group. Such concerns were first raised by Qu Qiubai in 1931, an early Chinese communist revolutionary leader. His concern echoed within the Communist Party, which adopted the name Putonghua in 1955. Since 1949, usage of the word Guóyǔ was phased out in the PRC, only surviving in established compound nouns, e.g. Guóyǔ liúxíng yīnyuè (国语流行音乐, colloquially Mandarin pop), Guóyǔ piān or Guóyǔ diànyǐng (国语片/国语电影, colloquially Mandarin cinema).

In Taiwan, Guóyǔ (the national language) has been the colloquial term for Standard Northern Mandarin. In 2017 and 2018, the Taiwanese government introduced two laws to explicitly recognize indigenous Formosan languages and Hakka to be the "Languages of the nation" (國家語言, note the plural form) along with Standard Northern Mandarin. Since then, there have been efforts to reclaim the term "national language" (Guóyǔ) to encompass all "languages of the nation" rather than exclusively referring to Standard Northern Mandarin.

Hanyu and Zhongwen

Among Chinese people, Hànyǔ (漢語; 汉语) or the "Sinitic languages" refer to all language varieties of the Han people. Zhōngwén (中文) or the "Chinese written language", refers to all written languages of Chinese (Sinitic). However, gradually these two terms have been reappropriated to exclusively refer to one particular Sinitic language, the Standard Northern Mandarin, a.k.a. Standard Chinese. This imprecise usage would lead to situations in areas such as Taiwan, Malaysia, and Singapore as follows:

- (1) A Standard Northern Mandarin speaker approaches speakers of other varieties of Chinese and asks, "Do you speak Zhōngwén?" This would be deemed disrespectful.

- (2) A native speaker of certain varieties of Chinese admits that his/her spoken Zhōngwén is poor.

On the other hand, among foreigners, the term Hànyǔ is most commonly used in textbooks and standardized testing of Standard Chinese for foreigners, e.g. Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi.

Huayu

Huáyǔ (華語; 华语), or "language among the Chinese nation", up until the mid 1960s, refers to all language varieties among the Chinese nation. For example, Cantonese films, Hokkien films (廈語片) and Mandarin films produced in Hong Kong that got imported into Malaysia were collectively known as Huáyǔ cinema up until the mid-1960s. However, gradually it has been reappropriated to exclusively refer to one particular language among the Chinese nation, Standard Northern Mandarin, a.k.a. Standard Chinese. This term is mostly used in Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines.

History

The Chinese have different languages in different provinces, to such an extent that they cannot understand each other.... [They] also have another language which is like a universal and common language; this is the official language of the mandarins and of the court; it is among them like Latin among ourselves.... Two of our fathers [Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci] have been learning this mandarin language...

— Alessandro Valignano, Historia del Principio y Progresso de la Compañia de Jesus en las Indias Orientales (1542–1564)

Chinese has long had considerable dialectal variation, hence prestige dialects have always existed, and linguae francae have always been needed. Confucius, for example, used yǎyán (雅言; 'elegant speech') rather than colloquial regional dialects; text during the Han dynasty also referred to tōngyǔ (通語; 'common language'). Rime books, which were written since the Northern and Southern dynasties, may also have reflected one or more systems of standard pronunciation during those times. However, all of these standard dialects were probably unknown outside the educated elite; even among the elite, pronunciations may have been very different, as the unifying factor of all Chinese dialects, Classical Chinese, was a written standard, not a spoken one.

Late empire

The Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) began to use the term guānhuà (官話; 官话), or "official speech", to refer to the speech used at the courts. The term "Mandarin" is borrowed directly from Portuguese. The Portuguese word mandarim, derived from the Sanskrit word mantrin "counselor or minister", was first used to refer to the Chinese bureaucratic officials. The Portuguese then translated guānhuà as "the language of the mandarins" or "the mandarin language".

In the 17th century, the Empire had set up Orthoepy Academies (正音書院; Zhèngyīn Shūyuàn) in an attempt to make pronunciation conform to the standard. But these attempts had little success, since as late as the 19th century the emperor had difficulty understanding some of his own ministers in court, who did not always try to follow any standard pronunciation.

Before the 19th century, the standard was based on the Nanjing dialect, but later the Beijing dialect became increasingly influential, despite the mix of officials and commoners speaking various dialects in the capital, Beijing. By some accounts, as late as the early 20th century, the position of Nanjing Mandarin was considered to be higher than that of Beijing by some and the postal romanization standards set in 1906 included spellings with elements of Nanjing pronunciation. Nevertheless, by 1909, the dying Qing dynasty had established the Beijing dialect as guóyǔ (國語; 国语), or the "national language".

As the island of Taiwan had fallen under Japanese rule per the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki, the term kokugo (Japanese: 國語, "national language") referred to the Japanese language until the handover to the Republic of China in 1945.

Modern China

After the Republic of China was established in 1912, there was more success in promoting a common national language. A Commission on the Unification of Pronunciation was convened with delegates from the entire country. A Dictionary of National Pronunciation (國音字典; 国音字典) was published in 1919, defining a hybrid pronunciation that did not match any existing speech. Meanwhile, despite the lack of a workable standardized pronunciation, colloquial literature in written vernacular Chinese continued to develop apace.

Gradually, the members of the National Language Commission came to settle upon the Beijing dialect, which became the major source of standard national pronunciation due to its prestigious status. In 1932, the commission published the Vocabulary of National Pronunciation for Everyday Use (國音常用字彙; 国音常用字汇), with little fanfare or official announcement. This dictionary was similar to the previous published one except that it normalized the pronunciations for all characters into the pronunciation of the Beijing dialect. Elements from other dialects continue to exist in the standard language, but as exceptions rather than the rule.

After the Chinese Civil War, the People's Republic of China continued the effort, and in 1955, officially renamed guóyǔ as pǔtōnghuà (simplified Chinese: 普通话; traditional Chinese: 普通話), or "common speech". By contrast, the name guóyǔ continued to be used by the Republic of China which, after its 1949 loss in the Chinese Civil War, was left with a territory consisting only of Taiwan and some smaller islands in its retreat to Taiwan. Since then, the standards used in the PRC and Taiwan have diverged somewhat, especially in newer vocabulary terms, and a little in pronunciation.

In 1956, the standard language of the People's Republic of China was officially defined as: "Pǔtōnghuà is the standard form of Modern Chinese with the Beijing phonological system as its norm of pronunciation, and Northern dialects as its base dialect, and looking to exemplary modern works in báihuà 'vernacular literary language' for its grammatical norms." By the official definition, Standard Chinese uses:

- The phonology or sound system of Beijing. A distinction should be made between the sound system of a variety and the actual pronunciation of words in it. The pronunciations of words chosen for the standardized language do not necessarily reproduce all of those of the Beijing dialect. The pronunciation of words is a standardization choice and occasional standardization differences (not accents) do exist, between Putonghua and Guoyu, for example.

- The vocabulary of Mandarin dialects in general. This means that all slang and other elements deemed "regionalisms" are excluded. On the one hand, the vocabulary of all Chinese varieties, especially in more technical fields like science, law, and government, are very similar. (This is similar to the profusion of Latin and Greek words in European languages.) This means that much of the vocabulary of Standard Chinese is shared with all varieties of Chinese. On the other hand, much of the colloquial vocabulary of the Beijing dialect is not included in Standard Chinese, and may not be understood by people outside Beijing.

- The grammar and idiom of exemplary modern Chinese literature, such as the work of Lu Xun, collectively known as "vernacular" (báihuà). Modern written vernacular Chinese is in turn based loosely upon a mixture of northern (predominant), southern, and classical grammar and usage. This gives formal Standard Chinese structure a slightly different feel from that of the street Beijing dialect.

At first, proficiency in the new standard was limited, even among speakers of Mandarin dialects, but this improved over the following decades.

|

|

Early 1950s | 1984 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehension | Comprehension | Speaking | |

| Mandarin dialect areas | 54 | 91 | 54 |

| non-Mandarin areas | 11 | 77 | 40 |

| whole country | 41 | 90 | 50 |

A survey conducted by the China's Education Ministry in 2007 indicated that 53.06% of the population were able to effectively communicate orally in Standard Chinese.

Current role

From an official point of view, Standard Chinese serves the purpose of a lingua franca—a way for speakers of the several mutually unintelligible varieties of Chinese, as well as the ethnic minorities in China, to communicate with each other. The very name Pǔtōnghuà, or "common speech," reinforces this idea. In practice, however, due to Standard Chinese being a "public" lingua franca, other Chinese varieties and even non-Sinitic languages have shown signs of losing ground to the standard.

While the Chinese government has been actively promoting Pǔtōnghuà on TV, radio and public services like buses to ease communication barriers in the country, developing Pǔtōnghuà as the official common language of the country has been challenging due to the presence of various ethnic groups which fear for the loss of their cultural identity and native dialect. In the summer of 2010, reports of increasing the use of the Pǔtōnghuà in local TV broadcasting in Guangdong led to thousands of Cantonese-speaking citizens in demonstration on the street.

In both mainland China and Taiwan, the use of Mandarin as the medium of instruction in the educational system and in the media has contributed to the spread of Mandarin. As a result, Mandarin is now spoken by most people in mainland China and Taiwan, though often with some regional or personal variation from the standard in terms of pronunciation or lexicon. However, the Ministry of Education in 2014 estimated that only about 70% of the population of China spoke Standard Mandarin to some degree, and only one tenth of those could speak it "fluently and articulately". There is also a 20% difference in penetration between eastern and western parts of China and a 50% difference between urban and rural areas. In addition, there are still 400 million Chinese who are only able to listen and understand Mandarin and not able to speak it. Therefore, in China's 13th Five Year Plan, the general goal is to raise the penetration rate to over 80% by 2020.

Mainland China and Taiwan use Standard Mandarin in most official contexts. The PRC in particular is keen to promote its use as a national lingua franca and has enacted a law (the National Common Language and Writing Law) which states that the government must "promote" Standard Mandarin. There is no explicit official intent to have Standard Chinese replace the regional varieties, but local governments have enacted regulations (such as the Guangdong National Language Regulations) which "implement" the national law by way of coercive measures to control the public use of regional spoken varieties and traditional characters in writing. In practice, some elderly or rural Chinese-language speakers do not speak Standard Chinese fluently, if at all, though most are able to understand it. But urban residents and the younger generations, who received their education with Standard Mandarin as the primary medium of education, are almost all fluent in a version of Standard Chinese, some to the extent of being unable to speak their local dialect.

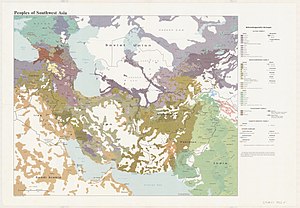

In the predominantly Han areas in mainland China, while the use of Standard Chinese is encouraged as the common working language, the PRC has been somewhat sensitive to the status of minority languages and, outside the education context, has generally not discouraged their social use. Standard Chinese is commonly used for practical reasons, as, in many parts of southern China, the linguistic diversity is so large that neighboring city dwellers may have difficulties communicating with each other without a lingua franca.

In Taiwan, the relationship between Standard Mandarin and other varieties, particularly Taiwanese Hokkien, has been more politically heated. During the martial law period under the Kuomintang (KMT) between 1949 and 1987, the KMT government revived the Mandarin Promotion Council and discouraged or, in some cases, forbade the use of Hokkien and other non-standard varieties. This produced a political backlash in the 1990s. Under the administration of Chen Shui-Bian, other Taiwanese varieties were taught in schools. The former president, Chen Shui-Bian, often spoke in Hokkien during speeches, while after the late 1990s, former President Lee Teng-hui, also speaks Hokkien openly. In an amendment to Article 14 of the Enforcement Rules of the Passport Act (護照條例施行細則) passed on 9 August 2019, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Taiwan) announced that Taiwanese can use the romanized spellings of their names in Hoklo, Hakka and Aboriginal languages for their passports. Previously, only Mandarin Chinese names could be romanized.

In Hong Kong and Macau, which are now special administrative regions of the People's Republic of China, Cantonese is the primary language spoken by the majority of the population and used by government and in their respective legislatures. After Hong Kong's handover from the United Kingdom and Macau's handover from Portugal, their governments use Putonghua to communicate with the Central People's Government of the PRC. There have been widespread efforts to promote usage of Putonghua in Hong Kong since the handover, with specific efforts to train police and teachers.

In Singapore, the government has heavily promoted a "Speak Mandarin Campaign" since the late 1970s, with the use of other Chinese varieties in broadcast media being prohibited and their use in any context officially discouraged until recently. This has led to some resentment amongst the older generations, as Singapore's migrant Chinese community is made up almost entirely of people of south Chinese descent. Lee Kuan Yew, the initiator of the campaign, admitted that to most Chinese Singaporeans, Mandarin was a "stepmother tongue" rather than a true mother language. Nevertheless, he saw the need for a unified language among the Chinese community not biased in favor of any existing group.

Mandarin is now spreading overseas beyond East Asia and Southeast Asia as well. In New York City, the use of Cantonese that dominated the Manhattan Chinatown for decades is being rapidly swept aside by Mandarin, the lingua franca of most of the latest Chinese immigrants.

Standard Chinese and the educational system

In both the PRC and Taiwan, Standard Chinese is taught by immersion starting in elementary school. After the second grade, the entire educational system is in Standard Chinese, except for local language classes that have been taught for a few hours each week in Taiwan starting in the mid-1990s.

In December 2004, the first survey of language use in the People's Republic of China revealed that only 53% of its population, about 700 million people, could communicate in Standard Chinese. This 53% is defined as a passing grade above 3-B (a score above 60%) of the Evaluation Exam.

With the fast development of the country and the massive internal migration in China, the standard Putonghua Proficiency Test has quickly become popular. Many university graduates in mainland China take this exam before looking for a job. Employers often require varying proficiency in Standard Chinese from applicants depending on the nature of the positions. Applicants of some positions, e.g. telephone operators, may be required to obtain a certificate. People raised in Beijing are sometimes considered inherently 1-A (A score of at least 97%) and exempted from this requirement. As for the rest, the score of 1-A is rare. According to the official definition of proficiency levels, people who get 1-B (A score of at least 92%) are considered qualified to work as television correspondents or in broadcasting stations 2-A (A score of at least 87%) can work as Chinese Literature Course teachers in public schools. Other levels include: 2-B (A score of at least 80%), 3-A (A score of at least 70%) and 3-B (A score of at least 60%). In China, a proficiency of level 3-B usually cannot be achieved unless special training is received. Even though many Chinese do not speak with standard pronunciation, spoken Standard Chinese is widely understood to some degree.

The China National Language And Character Working Committee was founded in 1985. One of its important responsibilities is to promote Standard Chinese proficiency for Chinese native speakers.

Phonology

The usual unit of analysis is the syllable, consisting of an optional initial consonant, an optional medial glide, a main vowel and an optional coda, and further distinguished by a tone.

|

|

Labial | Alveolar | Dental sibilants | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops | unaspirated | p ⟨b⟩ | t ⟨d⟩ | t͡s ⟨z⟩ | ʈ͡ʂ ⟨zh⟩ | t͡ɕ ⟨j⟩ | k ⟨g⟩ |

| aspirated | pʰ ⟨p⟩ | tʰ ⟨t⟩ | t͡sʰ ⟨c⟩ | ʈ͡ʂʰ ⟨ch⟩ | t͡ɕʰ ⟨q⟩ | kʰ ⟨k⟩ | |

| Nasals | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ |

| ||||

| Fricatives | f ⟨f⟩ | s ⟨s⟩ | ʂ ⟨sh⟩ | ɕ ⟨x⟩ | x ⟨h⟩ | ||

| Approximants | w ⟨w⟩ | l ⟨l⟩ | ɻ~ʐ ⟨r⟩ | j ⟨y⟩ |

| ||

The palatal initials [tɕ], [tɕʰ] and [ɕ] pose a classic problem of phonemic analysis. Since they occur only before high front vowels, they are in complementary distribution with three other series, the dental sibilants, retroflexes and velars, which never occur in this position.

| ɹ̩ ⟨i⟩ | ɤ ⟨e⟩ | a ⟨a⟩ | ei ⟨ei⟩ | ai ⟨ai⟩ | ou ⟨ou⟩ | au ⟨ao⟩ | ən ⟨en⟩ | an ⟨an⟩ | əŋ ⟨eng⟩ | aŋ ⟨ang⟩ | ɚ ⟨er⟩ |

| i ⟨i⟩ | ie ⟨ie⟩ | ia ⟨ia⟩ | iou ⟨iu⟩ | iau ⟨iao⟩ | in ⟨in⟩ | ien ⟨ian⟩ | iŋ ⟨ing⟩ | iaŋ ⟨iang⟩ |

| ||

| u ⟨u⟩ | uo ⟨uo⟩ | ua ⟨ua⟩ | uei ⟨ui⟩ | uai ⟨uai⟩ | uən ⟨un⟩ | uan ⟨uan⟩ | uŋ ⟨ong⟩ | uaŋ ⟨uang⟩ |

| ||

| y ⟨ü⟩ | ye ⟨üe⟩ | yn ⟨un⟩ | yen ⟨uan⟩ | iuŋ ⟨iong⟩ |

|

The [ɹ̩] final, which occurs only after dental sibilant and retroflex initials, is a syllabic approximant, prolonging the initial.

The rhotacized vowel [ɚ] forms a complete syllable. A reduced form of this syllable occurs as a sub-syllabic suffix, spelled -r in pinyin and often with a diminutive connotation. The suffix modifies the coda of the base syllable in a rhotacizing process called erhua.

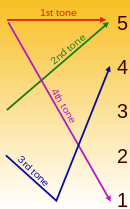

Each full syllable is pronounced with a phonemically distinctive pitch contour. There are four tonal categories, marked in pinyin with iconic diacritic symbols, as in the words mā (媽; 妈; "mother"), má (麻; "hemp"), mǎ (馬; 马; "horse") and mà (罵; 骂; "curse"). The tonal categories also have secondary characteristics. For example, the third tone is long and murmured, whereas the fourth tone is relatively short. Statistically, vowels and tones are of similar importance in the language.

There are also weak syllables, including grammatical particles such as the interrogative ma (嗎; 吗) and certain syllables in polysyllabic words. These syllables are short, with their pitch determined by the preceding syllable. Such syllables are commonly described as being in the neutral tone.

Regional accents

It is common for Standard Chinese to be spoken with the speaker's regional accent, depending on factors such as age, level of education, and the need and frequency to speak in official or formal situations. This appears to be changing, though, in large urban areas, as social changes, migrations, and urbanization take place.

Due to evolution and standardization, Mandarin, although based on the Beijing dialect, is no longer synonymous with it. Part of this was due to the standardization to reflect a greater vocabulary scheme and a more archaic and "proper-sounding" pronunciation and vocabulary.

Distinctive features of the Beijing dialect are more extensive use of erhua in vocabulary items that are left unadorned in descriptions of the standard such as the Xiandai Hanyu Cidian, as well as more neutral tones. An example of standard versus Beijing dialect would be the standard mén (door) and Beijing ménr.

Most Standard Chinese as spoken on Taiwan differs mostly in the tones of some words as well as some vocabulary. Minimal use of the neutral tone and erhua, and technical vocabulary constitute the greatest divergences between the two forms.

The stereotypical "southern Chinese" accent does not distinguish between retroflex and alveolar consonants, pronouncing pinyin zh [tʂ], ch [tʂʰ], and sh [ʂ] in the same way as z [ts], c [tsʰ], and s [s] respectively. Southern-accented Standard Chinese may also interchange l and n, final n and ng, and vowels i and ü [y]. Attitudes towards southern accents, particularly the Cantonese accent, range from disdain to admiration.

Romanization and script

While there is a standard dialect among different varieties of Chinese, there is no "standard script". In mainland China, Singapore and Malaysia, standard Chinese is rendered in simplified Chinese characters; while in Taiwan it is rendered in traditional. As for the romanization of standard Chinese, Hanyu Pinyin is the most dominant system globally, while Taiwan stick to the older Bopomofo system.

Grammar

Chinese is a strongly analytic language, having almost no inflectional morphemes, and relying on word order and particles to express relationships between the parts of a sentence. Nouns are not marked for case and rarely marked for number. Verbs are not marked for agreement or grammatical tense, but aspect is marked using post-verbal particles.

The basic word order is subject–verb–object (SVO), as in English. Nouns are generally preceded by any modifiers (adjectives, possessives and relative clauses), and verbs also generally follow any modifiers (adverbs, auxiliary verbs and prepositional phrases).

他

Tā

He

为/為

wèi

for

他的

tā-de

he-GEN

朋友

péngyǒu

friend

做了

zuò-le

do-PERF

这个/這個

zhè-ge

this-CL

工作。

gōngzuò.

job

'He did this job for his friends.'

The predicate can be an intransitive verb, a transitive verb followed by a direct object, a copula (linking verb) shì (是) followed by a noun phrase, etc. In predicative use, Chinese adjectives function as stative verbs, forming complete predicates in their own right without a copula. For example,

我

Wǒ

I

不

bú

not

累。

lèi.

tired

'I am not tired.'

Another example is the common greeting nǐ hăo (你好), literally "you good".

Chinese additionally differs from English in that it forms another kind of sentence by stating a topic and following it by a comment. To do this in English, speakers generally flag the topic of a sentence by prefacing it with "as for". For example:

妈妈/媽媽

Māma

Mom

给/給

gěi

give

我们/我們

wǒmen

us

的

de

REL

钱/錢,

qián,

money

我

wǒ

I

已经/已經

yǐjīng

already

买了/買了

mǎi-le

buy-PERF

糖果。

tángguǒ(r)

candy

'As for the money that Mom gave us, I have already bought candy with it.'

The time when something happens can be given by an explicit term such as "yesterday," by relative terms such as "formerly," etc.

As in many east Asian languages, classifiers or measure words are required when using numerals, demonstratives and similar quantifiers. There are many different classifiers in the language, and each noun generally has a particular classifier associated with it.

一顶

yī-dǐng

one-top

帽子,

màozi,

hat

三本

sān-běn

three-volume

书/書,

shū,

book

那支

nèi-zhī

that-branch

笔/筆

bǐ

pen

'a hat, three books, that pen'

The general classifier ge (个/個) is gradually replacing specific classifiers.

Vocabulary

Many honorifics that were in use in imperial China have not been used in daily conversation in modern-day Mandarin, such as jiàn (賤; 贱; "my humble") and guì (貴; 贵; "your honorable").

Although Chinese speakers make a clear distinction between Standard Chinese and the Beijing dialect, there are aspects of Beijing dialect that have made it into the official standard. Standard Chinese has a T–V distinction between the polite and informal "you" that comes from the Beijing dialect, although its use is quite diminished in daily speech. It also distinguishes between "zánmen" (we including the listener) and "wǒmen" (we not including the listener). In practice, neither distinction is commonly used by most Chinese, at least outside the Beijing area.

The following samples are some phrases from the Beijing dialect which are not yet accepted into Standard Chinese:

- 倍儿 bèir means 'very much'; 拌蒜 bànsuàn means 'stagger'; 不吝 bù lìn means 'do not worry about'; 撮 cuō means 'eat'; 出溜 chūliū means 'slip'; (大)老爷儿们儿 dà lǎoyermenr means 'man, male'.

The following samples are some phrases from Beijing dialect which have become accepted as Standard Chinese:

- 二把刀 èr bǎ dāo means 'not very skillful'; 哥们儿 gēménr means 'good male friend(s)', 'buddy(ies)'; 抠门儿 kōu ménr means 'frugal' or 'stingy'.

Writing system

Standard Chinese is written with characters corresponding to syllables of the language, most of which represent a morpheme. In most cases, these characters come from those used in Classical Chinese to write cognate morphemes of late Old Chinese, though their pronunciation, and often meaning, has shifted dramatically over two millennia. However, there are several words, many of them heavily used, which have no classical counterpart or whose etymology is obscure. Two strategies have been used to write such words:

- An unrelated character with the same or similar pronunciation might be used, especially if its original sense was no longer common. For example, the demonstrative pronouns zhè "this" and nà "that" have no counterparts in Classical Chinese, which used 此 cǐ and 彼 bǐ respectively. Hence the character 這 (later simplified as 这) for zhè "to meet" was borrowed to write zhè "this", and the character 那 for nà, the name of a country and later a rare surname, was borrowed to write nà "that".

- A new character, usually a phono-semantic or semantic compound, might be created. For example, gǎn "pursue, overtake", is written with a new character 趕, composed of the signific 走 zǒu "run" and the phonetic 旱 hàn "drought". This method was used to represent many elements in the periodic table.

The government of the PRC (as well as some other governments and institutions) has promulgated a set of simplified forms. Under this system, the forms of the words zhèlǐ ("here") and nàlǐ ("there") changed from 這裏/這裡 and 那裏/那裡 to 这里 and 那里, among many other changes.

Chinese characters were traditionally read from top to bottom, right to left, but in modern usage it is more common to read from left to right.

Examples

| English | Traditional characters | Simplified characters | Pinyin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hello! | 你好! | Nǐ hǎo! | |

| What is your name? | 你叫什麼名字? | 你叫什么名字? | Nǐ jiào shénme míngzi? |

| My name is... | 我叫... | Wǒ jiào ... | |

| How are you? | 你好嗎?/ 你怎麼樣? | 你好吗?/ 你怎么样? | Nǐ hǎo ma? / Nǐ zěnmeyàng? |

| I am fine, how about you? | 我很好,你呢? | Wǒ hěn hǎo, nǐ ne? | |

| I don't want it / I don't want to | 我不要。 | Wǒ bú yào. | |

| Thank you! | 謝謝! | 谢谢! | Xièxie |

| Welcome! / You're welcome! (Literally: No need to thank me!) / Don't mention it! (Literally: Don't be so polite!) | 歡迎!/ 不用謝!/ 不客氣! | 欢迎!/ 不用谢!/ 不客气! | Huānyíng! / Búyòng xiè! / Bú kèqì! |

| Yes. / Correct. | 是。 / 對。/ 嗯。 | 是。 / 对。/ 嗯。 | Shì. / Duì. / M. |

| No. / Incorrect. | 不是。/ 不對。/ 不。 | 不是。/ 不对。/ 不。 | Búshì. / Bú duì. / Bù. |

| When? | 什麼時候? | 什么时候? | Shénme shíhou? |

| How much money? | 多少錢? | 多少钱? | Duōshǎo qián? |

| Can you speak a little slower? | 您能說得再慢些嗎? | 您能说得再慢些吗? | Nín néng shuō de zài mànxiē ma? |

| Good morning! / Good morning! | 早上好! / 早安! | Zǎoshang hǎo! / Zǎo'ān! | |

| Goodbye! | 再見! | 再见! | Zàijiàn! |

| How do you get to the airport? | 去機場怎麼走? | 去机场怎么走? | Qù jīchǎng zěnme zǒu? |

| I want to fly to London on the eighteenth | 我想18號坐飛機到倫敦。 | 我想18号坐飞机到伦敦。 | Wǒ xiǎng shíbā hào zuò fēijī dào Lúndūn. |

| How much will it cost to get to Munich? | 到慕尼黑要多少錢? | 到慕尼黑要多少钱? | Dào Mùníhēi yào duōshǎo qián? |

| I don't speak Chinese very well. | 我的漢語說得不太好。 | 我的汉语说得不太好。 | Wǒ de Hànyǔ shuō de bú tài hǎo. |

| Do you speak English? | 你會說英語嗎? | 你会说英语吗? | Nǐ huì shuō Yīngyǔ ma? |

| I have no money. | 我沒有錢。 | 我没有钱。 | Wǒ méiyǒu qián. |