The Hollywood blacklist was the colloquial term for what was in actuality a broader entertainment industry blacklist put in effect in the mid-20th century in the United States during the early years of the Cold War. The blacklist involved the practice of denying employment to entertainment industry professionals believed to be or to have been Communists or sympathizers. Not just actors, but screenwriters, directors, musicians, and other American entertainment professionals were barred from work by the studios. This was usually done on the basis of their membership in, alleged membership in, or sympathy with the Communist Party USA, or on the basis of their refusal to assist Congressional investigations into the party's activities. Even during the period of its strictest enforcement, from the late 1940s through to the late 1950s, the blacklist was rarely made explicit or easily verifiable, as it was the result of numerous individual decisions by the studios and was not the result of official legal action. Nevertheless, it quickly and directly damaged or ended the careers and income of scores of individuals working in the film industry.

Hollywood Ten

The first systematic Hollywood blacklist was instituted on November 25, 1947, the day after ten writers and directors were cited for contempt of Congress for refusing to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). These personalities were subpoenaed to appear before HUAC in October. The contempt citation included a criminal charge, which led to a highly publicized trial and an eventual conviction with a maximum of one year in jail in addition to a $1,000 fine. The Congressional action prompted a group of studio executives, acting under the aegis of the Association of Motion Picture Producers, to fire the artists – the so-called Hollywood Ten – and made what has become known as the Waldorf Statement. It was announced via a news release after the major producers met at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel and it included a condemnation of the personalities involved, effectively ostracizing those named from the industry. These producers instituted compulsory oaths of loyalty from their employees with the threat of a blacklist.

Blacklist

On June 22, 1950, a pamphlet entitled Red Channels was published. Focused on the field of broadcasting, it identified 151 entertainment industry professionals in the context of "Red Fascists and their sympathizers". Soon, most of those named, along with a host of other artists, were barred from employment in most of the entertainment field.

The blacklist lasted until 1960, when Dalton Trumbo, a Communist Party member from 1943 to 1948 and member of the Hollywood Ten, was credited as the screenwriter of the film Exodus (1960), and publicly acknowledged by actor Kirk Douglas for writing the screenplay for Spartacus (also 1960). Many of those blacklisted, however, were still barred from work in their professions for years afterward.

History

Background

The Hollywood blacklist was rooted in events of the 1930s and the early 1940s, encompassing the height of the Great Depression and World War II. Two major film industry strikes during the 1930s increased tensions between the Hollywood producers and the unions, particularly the Screen Writers Guild.

The Communist Party USA (CPUSA) lost substantial support after the Moscow show trials of 1936–1938 and the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 1939. The U.S. government began turning its attention to the possible links between Hollywood and the party during this period. Under then-chairman Martin Dies, Jr., the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) released a report in 1938 claiming that communism was pervasive in Hollywood. Two years later, Dies privately took testimony from a former Communist Party member, John L. Leech, who named forty-two movie industry professionals as Communists. After Leech repeated his charges in supposed confidence to a Los Angeles grand jury, many of the names were reported in the press, including those of stars Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney, Katharine Hepburn, Melvyn Douglas and Fredric March, among other Hollywood figures. Dies said he would "clear" all those who co-operated by meeting with him in what he called "executive session". Within two weeks of the grand jury leak, all those on the list except for actress Jean Muir had met with the HUAC chairman. Dies "cleared" everyone except actor Lionel Stander, who was fired by the movie studio, Republic Pictures, where he was under contract.

In 1941, producer Walt Disney took out an ad in Variety, the industry trade magazine, declaring his conviction that "Communist agitation" was behind a cartoonists and animators' strike. According to historians Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund, "In actuality, the strike had resulted from Disney's overbearing paternalism, high-handedness, and insensitivity." Inspired by Disney, California State Senator Jack Tenney, chairman of the state legislature's Joint Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities, launched an investigation of "Reds in movies". The probe fell flat, and was mocked in several Variety headlines.

The subsequent wartime alliance between the United States and the Soviet Union brought the CPUSA newfound credibility. During the war, membership in the party reached a peak of 50,000. As World War II drew to a close, perceptions changed again, with communism increasingly becoming a focus of American fears and hatred. In 1945, Gerald L. K. Smith, founder of the neofascist America First Party, began giving speeches in Los Angeles assailing the "alien minded Russian Jews in Hollywood". Mississippi congressman John E. Rankin, a member of HUAC, held a press conference to declare that "one of the most dangerous plots ever instigated for the overthrow of this Government has its headquarters in Hollywood ... the greatest hotbed of subversive activities in the United States". Rankin promised, "We're on the trail of the tarantula now". Reports of Soviet repression in Eastern and Central Europe in the war's aftermath added more fuel to what became known as the "Second Red Scare". The growth of conservative political influence and the Republican triumph in the 1946 Congressional elections, which saw the party take control of both the House and Senate, led to a major revival of institutional anticommunist activity, publicly spearheaded by HUAC. The following year, the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals (MPA), a political action group cofounded by Walt Disney, issued a pamphlet advising producers on the avoidance of "subtle communistic touches" in their films. Its counsel revolved around a list of ideological prohibitions, such as "Don't smear the free-enterprise system ... Don't smear industrialists ... Don't smear wealth ... Don't smear the profit motive ... Don't deify the 'common man' ... Don't glorify the collective".

Beginning (1946–1947)

On July 29, 1946, William R. Wilkerson, publisher and founder of The Hollywood Reporter, published a "TradeView" column entitled "A Vote For Joe Stalin". It named as Communist sympathizers Dalton Trumbo, Maurice Rapf, Lester Cole, Howard Koch, Harold Buchman, John Wexley, Ring Lardner Jr., Harold Salemson, Henry Meyers, Theodore Strauss, and John Howard Lawson. In August and September 1946, Wilkerson published other columns containing names of numerous purported Communists and sympathizers. They became known as "Billy's List" and "Billy's Blacklist". In 1962, when Wilkerson died, his THR obituary stated he had "named names, pseudonyms and card numbers and was widely credited with being chiefly responsible for preventing communists from becoming entrenched in Hollywood production – something that foreign film unions have been unable to do." In a 65th-anniversary article in 2012, Wilkerson's son apologized for the paper's role in the blacklist, stating that his father was motivated by revenge for his own thwarted ambition to own a studio.

In October 1947, drawing upon the list named in The Hollywood Reporter, the House Un-American Activities Committee subpoenaed a number of persons working in the Hollywood film industry to testify at hearings. The committee had declared its intention to investigate whether Communist agents and sympathizers had been planting propaganda in American films.

The hearings began with appearances by Walt Disney and Ronald Reagan, then president of the Screen Actors Guild. Disney testified that the threat of Communists in the film industry was a serious one, and named specific people who had worked for him as probable Communists. Reagan testified that a small clique within his union was using "communist-like tactics" in attempting to steer union policy, but that he did not know if those (unnamed) members were communists or not, and that in any case he thought the union had them under control. (Later his first wife, actress Jane Wyman, stated in her biography written with Joe Morella [1985] that Reagan's allegations against friends and colleagues led to tension in their marriage, eventually resulting in their divorce.) Actor Adolphe Menjou declared: "I am a witch hunter if the witches are Communists. I am a Red-baiter. I would like to see them all back in Russia."

In contrast, other leading Hollywood figures, including director John Huston and actors Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Judy Garland and Danny Kaye, organized the Committee for the First Amendment to protest the government's targeting of the film industry. Members of the committee, such as Sterling Hayden, assured Bogart that they were not Communists. During the hearings, a local Washington paper reported that Hayden was a Communist. After returning to Hollywood, Bogart shouted at Danny Kaye, "You fuckers sold me out." The group came under attack as being naive or foolish. Under pressure from his studio, Warner Bros., to distance himself from the Hollywood Ten, Bogart negotiated a statement that did not denounce the committee, but said that his trip was "ill-advised, even foolish". Billy Wilder told the group that "we oughta fold".

Many of the film industry professionals in whom HUAC had expressed interest were alleged to have been members of the Communist Party USA. Of the 43 people put on the witness list, 19 declared that they would not give evidence. Eleven of these 19 were called before the committee. Members of the Committee for the First Amendment flew to Washington ahead of this climactic phase of the hearing, which commenced on Monday, October 27. Of the eleven "unfriendly witnesses", one, émigré playwright Bertolt Brecht, ultimately chose to answer the committee's questions (following which he left the country). The other ten refused, citing their First Amendment rights to freedom of speech and assembly. Included among the questions they refused to answer was one now generally rendered as "Are you now, or have you ever been, a member of the Communist Party?". The Committee formally accused these ten of contempt of Congress, and began criminal proceedings against them in the full House of Representatives.

In light of the "Hollywood Ten"'s defiance of HUAC – in addition to refusing to testify, many had tried to read statements decrying the committee's investigation as unconstitutional – political pressure mounted on the film industry to demonstrate its "anti-subversive" bona fides. Late in the hearings, Eric Johnston, president of the Association of Motion Picture Producers (AMPP) (and Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA)), declared to the committee that he would never "employ any proven or admitted Communist because they are just a disruptive force, and I don't want them around".

On November 17, the Screen Actors Guild voted to make its officers swear a pledge asserting each was not a Communist. The following week, on November 24, the House of Representatives voted 346 to 17 to approve citations against the Hollywood Ten for contempt of Congress. The next day, following a meeting of film industry executives at New York's Waldorf-Astoria hotel, AMPP President Johnston issued a press release that is today referred to as the Waldorf Statement. Their statement said that the ten would be fired or suspended without pay and not re-employed until they were cleared of contempt charges and had sworn that they were not Communists. The first Hollywood blacklist was in effect.

Growth (1948–1950)

The HUAC hearings failed to turn up any evidence that Hollywood was secretly disseminating Communist propaganda, but the industry was nonetheless transformed. The fallout from the inquiry was a factor in the decision by Floyd Odlum, the primary owner of RKO Pictures, to leave the industry. As a result, the studio passed into the hands of Howard Hughes. Within weeks of taking over in May 1948, Hughes fired most of RKO's employees and virtually shut the studio down for six months as he had the political sympathies of the rest investigated. Then, just as RKO swung back into production, Hughes made the decision to settle a long-standing federal antitrust suit against the industry's Big Five studios. This was one of the crucial steps in the collapse of the studio system that had governed Hollywood for a quarter-century.

In early 1948, all of the Hollywood Ten were convicted of contempt. Following a series of unsuccessful appeals, the cases arrived before the Supreme Court; among the submissions filed in defense of the ten was an amicus curiae brief signed by 204 Hollywood professionals. After the court denied review, the Hollywood Ten began serving one-year prison sentences in 1950. One of the Ten, screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, stated in the documentary film Hollywood On Trial (1976):

As far as I was concerned, it was a completely just verdict. I had contempt for that Congress and have had contempt for several since. And on the basis of guilt or innocence, I could never really complain very much. That this was a crime or misdemeanor was the complaint, my complaint.

In September 1950, one of the Ten, director Edward Dmytryk, publicly announced that he had once been a Communist and was prepared to give evidence against others who had been as well. He was released early from jail; following his 1951 HUAC appearance, in which he described his brief membership in the party and named names, his career recovered.

The others remained silent and most were unable to obtain work in the American film and television industry for many years. Adrian Scott, who had produced four of Dmytryk's films – Murder, My Sweet; Cornered; So Well Remembered; and Crossfire – was one of those named by his former friend. Scott's next screen credit did not come until 1972 and he never produced another feature film. Some of those blacklisted continued to write for Hollywood or the broadcasting industry surreptitiously, using pseudonyms or the names of friends who posed as the actual writers (those who allowed their names to be used in this fashion were called "fronts"). Of the 204 who signed the amicus brief, 84 were themselves blacklisted. There was a more general chilling effect: Humphrey Bogart, who had been one of the most prominent members of the Committee for the First Amendment, felt compelled to write an article for Photoplay magazine denying he was a Communist sympathizer. The Tenney Committee, which had continued its state-level investigations, summoned songwriter Ira Gershwin to testify about his participation in the committee.

A number of non-governmental organizations participated in enforcing and expanding the blacklist; in particular, the American Legion, the conservative war veterans' group, was instrumental in pressuring the entertainment industry to exclude communists and their sympathizers. In 1949, the Americanism Division of the Legion issued its own blacklist – a roster of 128 people whom it claimed were participants in the "Communist Conspiracy". Among the names on the Legion's list was that of the playwright Lillian Hellman. Hellman had written or contributed to the screenplays of approximately ten motion pictures up to that point; she was not employed again by a Hollywood studio until 1966.

Another influential group was American Business Consultants Inc., founded in 1947. In the subscription information for its weekly publication Counterattack, "The Newsletter of Facts to Combat Communism", it declared that it was run by "a group of former FBI men. It has no affiliation whatsoever with any government agency." Notwithstanding that claim, it seems the editors of Counterattack had direct access to the files of both the Federal Bureau of Investigation and HUAC; the results of that access became widely apparent with the June 1950 publication of Red Channels. This Counterattack spinoff listed 151 people in entertainment and broadcast journalism, along with records of their involvement in what the pamphlet meant to be taken as Communist or pro-Communist activities. A few of those named, such as Hellman, were already being denied employment in the motion picture, TV, and radio fields; the publication of Red Channels meant that scores more were placed on the blacklist. That year, CBS instituted a loyalty oath which it required of all its employees.

Jean Muir was the first performer to lose employment because of a listing in Red Channels. In 1950, Muir was named as a Communist sympathizer in the pamphlet, and was immediately removed from the cast of the television sitcom The Aldrich Family, in which she had been cast as Mrs. Aldrich. NBC had received between 20 and 30 phone calls protesting her being in the show. General Foods, the sponsor, said that it would not sponsor programs in which "controversial persons" were featured. Though the company later received thousands of calls protesting the decision, it was not reversed.

HUAC return (1951–1952)

In 1951, with the U.S. Congress now under Democratic control, HUAC launched a second investigation of Hollywood and Communism. As actor Larry Parks said when called before the panel,

Don't present me with the choice of either being in contempt of this committee and going to jail or forcing me to really crawl through the mud to be an informer. For what purpose? I don't think it is a choice at all. I don't think this is really sportsmanlike. I don't think this is American. I don't think this is American justice.

Parks ultimately testified, becoming, however reluctantly, a "friendly witness", and found himself blacklisted, nonetheless.

In fact, the legal tactics of those refusing to testify had changed by this time; instead of relying on the First Amendment, they invoked the Fifth Amendment's shield against self-incrimination (although, as before, Communist Party membership was not illegal). While this usually allowed a witness to avoid "naming names" without being indicted for contempt of Congress, "taking the Fifth" before HUAC guaranteed one's membership on the industry blacklist. Historians at times distinguish between the relatively official blacklist – the names of those who (a) were called by HUAC and, in whatever manner, refused to co-operate and/or (b) were identified as Communists in the hearings – and the so-called graylist – those others who were denied work because of their political or personal affiliations, real or imagined; the consequences, however, were largely the same. The graylist also refers more specifically to those who were denied work by the major studios, but could still find jobs on Poverty Row: Composer Elmer Bernstein, for instance, was called by HUAC when it was discovered that he had written some music reviews for a Communist newspaper. After he refused to name names, pointing out that he had never attended a Communist Party meeting, he found himself composing music for movies such as Cat Women of the Moon.

Like Parks and Dmytryk, others also co-operated with the committee. Some friendly witnesses gave broadly damaging testimony with less apparent reluctance, most prominently director Elia Kazan and screenwriter Budd Schulberg. Their co-operation in describing the political leanings of their friends and professional associates effectively brought a halt to dozens of careers and compelled a number of artists to depart for Mexico or Europe. Others were also forced abroad in order to work. Director Jules Dassin was among the best known of these. Briefly a Communist, Dassin had left the party in 1939. He was immediately blacklisted after Edward Dmytryk and fellow filmmaker Frank Tuttle named him to HUAC in 1952. Dassin left for France, and spent much of his remaining career in Greece. Scholar Thomas Doherty describes how the HUAC hearings swept onto the blacklist those who had never even been particularly active politically, let alone suspected of being Communists:

[O]n March 21, 1951, the name of the actor Lionel Stander was uttered by the actor Larry Parks during testimony before HUAC. "Do you know Lionel Stander?" committee counsel Frank S. Tavenner inquired. Parks replied he knew the man, but had no knowledge of his political affiliations. No more was said about Stander either by Parks or the committee – no accusation, no insinuation. Yet Stander's phone stopped ringing. Prior to Parks's testimony, Stander had worked on ten television shows in the previous 100 days. Afterwards, nothing.

When Stander was himself called before HUAC, he began by pledging his full support in the fight against "subversive" activities:

I know of a group of fanatics who are desperately trying to undermine the Constitution of the United States by depriving artists and others of Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness without due process of law ... I can tell names and cite instances and I am one of the first victims of it ... [This is] a group of ex-Fascists and America-Firsters and anti-Semites, people who hate everybody, including Negroes, minority groups, and most likely themselves ... [T]hese people are engaged in a conspiracy outside all the legal processes to undermine the very fundamental American concepts upon which our entire system of democracy exists.

Stander was clearly speaking of the committee itself.

The hunt for subversives extended into every branch of the entertainment industry. In the field of animation, two studios in particular were affected: United Productions of America (UPA) was purged of a large portion of its staff, while New York-based Tempo was entirely crushed. HUAC investigations effectively destroyed families. Screenwriter Richard Collins, after a brief period on the blacklist, became a friendly witness and dumped his wife, actress Dorothy Comingore, who refused to name names. Divorcing Comingore, Collins took the couple's young son, as well. The family's story was later dramatized in the film Guilty by Suspicion (1991), in which the character based on Comingore "commits suicide rather than endure a long mental collapse". In real life, Comingore succumbed to alcoholism and died of a pulmonary disease at the age of fifty-eight. In the description of historians Paul Buhle and David Wagner, "premature strokes and heart attacks were fairly common [among blacklistees], along with heavy drinking as a form of suicide on the installment plan".

For all that, evidence that Communists were actually using Hollywood films as vehicles for subversion remained hard to come by. Schulberg reported that the manuscript of his novel What Makes Sammy Run? (later a screenplay, as well) had been subject to an ideological critique by Hollywood Ten writer John Howard Lawson, whose comments he had solicited. The significance of such interactions was questionable. As historian Gerald Horne describes, many Hollywood screenwriters had joined or associated with the local Communist Party chapter because it "offered a collective to a profession that was enmeshed in tremendous isolation at the typewriter. Their 'Writers' Clinic' had 'an informal "board" of respected screenwriters' – including Lawson and Ring Lardner Jr. – 'who read and commented upon any screenplay submitted to them. Although their criticism could be plentiful, stinging, and (sometimes) politically dogmatic, the author was entirely free to accept it or reject it as he or she pleased without incurring the slightest "consequence" or sanction.'" Much of the onscreen evidence of Communist influence uncovered by HUAC was feeble at best. One witness remembered Stander, while performing in a film, whistling the left-wing "Internationale" as his character waited for an elevator. "Another noted that screenwriter Lester Cole had inserted lines from a famous pro-Loyalist speech by La Pasionaria about it being 'better to die on your feet than to live on your knees' into a pep talk delivered by a football coach."

Others disagree about how Communists affected the film industry. The author Kenneth Billingsley, writing in Reason magazine, said that Trumbo wrote in The Daily Worker about films which he said communist influence in Hollywood had prevented from being made: among them were proposed adaptations of Arthur Koestler's anti-totalitarian works Darkness at Noon and The Yogi and the Commissar, which described the rise of communism in Russia. Authors Ronald and Allis Radosh, writing in Red Star over Hollywood: The Film Colony's Long Romance with the Left, said that Trumbo bragged about how he and other party members stopped anti-communist films from being produced.

Height (1952–1956)

In 1952, the Screen Writers Guild – which had been founded two decades before by three future members of the Hollywood Ten – authorized the movie studios to "omit from the screen" the names of any individuals who had failed to clear themselves before Congress. Writer Dalton Trumbo, for instance, one of the Hollywood Ten and still on the blacklist, had received screen credit in 1950 for writing, years earlier, the story on which the screenplay of Columbia Pictures' Emergency Wedding was based. There was no more of that until the 1960s. The name of Albert Maltz, who had written the original screenplay for The Robe in the mid-1940s, was nowhere to be seen when the movie was released in 1953.

As William O'Neill describes, pressure was maintained even on those who had ostensibly "cleared" themselves:

On December 27, 1952, the American Legion announced that it disapproved of a new film, Moulin Rouge, starring José Ferrer, who used to be no more progressive than hundreds of other actors and had already been grilled by HUAC. The picture itself was based on the life of Toulouse-Lautrec and was totally apolitical. Nine members of the Legion had picketed it anyway, giving rise to the controversy. By this time, people were not taking any chances. Ferrer immediately wired the Legion's national commander that he would be glad to join the veterans in their "fight against communism".

The group's efforts dragged many others onto the blacklist: In 1954, "[s]creenwriter Louis Pollock, a man without any known political views or associations, suddenly had his career yanked out from under him because the American Legion confused him with Louis Pollack, a California clothier, who had refused to co-operate with HUAC." Orson Bean recalled that he had briefly been placed on the blacklist after dating a member of the party, despite his own politics being conservative.

During this same period, a number of influential newspaper columnists covering the entertainment industry, including Walter Winchell, Hedda Hopper, Victor Riesel, Jack O'Brian, and George Sokolsky, regularly offered up names with the suggestion that they should be added to the blacklist. Actor John Ireland received an out-of-court settlement to end a 1954 lawsuit against the Young & Rubicam advertising agency, which had ordered him dropped from the lead role in a television series it sponsored. Variety described it as "the first industry admission of what has for some time been an open secret – that the threat of being labeled a political non-conformist, or worse, has been used against show business personalities, and that a screening system is at work determining these [actors'] availabilities for roles".

The Hollywood blacklist had long gone hand in hand with the Red-baiting activities of J. Edgar Hoover's FBI. Adversaries of HUAC such as lawyer Bartley Crum, who defended some of the Hollywood Ten in front of the committee in 1947, were labeled as Communist sympathizers or subversives and targeted for investigation themselves. Throughout the 1950s, the FBI tapped Crum's phones, opened his mail, and placed him under continuous surveillance. As a result, he lost most of his clients and, unable to cope with the stress of ceaseless harassment, committed suicide in 1959. Intimidating and dividing the left is now seen as a central purpose of the HUAC hearings. Fund-raising for once-popular humanitarian efforts became difficult, and despite the sympathies of many in the industry there was little open support in Hollywood for causes such as the Civil Rights Movement and opposition to nuclear weapons testing.

The struggles attending the blacklist were played out metaphorically on the big screen in various ways. As described by film historian James Chapman, "Carl Foreman, who had refused to testify before the committee, wrote the western High Noon (1952), in which a town marshal (played, ironically, by friendly witness Gary Cooper) finds himself deserted by the good citizens of Hadleyville (read: Hollywood) when a gang of outlaws who had terrorized the town several years earlier (read: HUAC) returns." Cooper's lawman cleaned up Hadleyville, but Foreman was forced to leave for Europe to find work. Meanwhile, Kazan and Schulberg collaborated on a movie widely seen as justifying their decision to name names. On the Waterfront (1954) became one of the most honored films in Hollywood history, winning eight Academy Awards, including Oscars for Best Film, Kazan's direction, and Schulberg's screenplay. The film featured Lee J. Cobb, one of the best known actors to name names. Time Out Film Guide argues that the film is "undermined" by its "embarrassing special pleading on behalf of informers".

After his release from prison, Herbert Biberman of the Hollywood Ten directed Salt of the Earth (also 1954), working independently in New Mexico with fellow blacklisted Hollywood professionals – producer Paul Jarrico, writer Michael Wilson, and actors Rosaura Revueltas and Will Geer. The film, concerning a strike by Mexican-American mine workers, was denounced as Communist propaganda when it was completed in 1953. Distributors boycotted it, newspapers and radio stations rejected advertisements for it, and the projectionists' union refused to run it. Nationwide in 1954, only around a dozen theaters exhibited it.

Break (1957–present)

Jules Dassin was one of the first to break the blacklist. Although he was named by Edward Dmytryk and Frank Tuttle in spring 1951, he directed in December 1952 the Broadway Play Two's Company with Bette Davis. In June 1956, his French film production Rififi opened at the Fine Arts Theater and stayed for 20 weeks.

A key figure in bringing an end to blacklisting was John Henry Faulk. Host of an afternoon comedy radio show, Faulk was a leftist active in his union, the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. He was scrutinized by AWARE, Inc., one of the private firms that examined individuals for signs of Communist sympathies and "disloyalty". Marked by the group as unfit, he was fired by CBS Radio. Almost alone among the many victims of blacklisting, Faulk decided to sue AWARE in 1957. Though the case dragged through the courts for years, the suit itself was an important symbol of the building resistance to the blacklist.

The initial cracks in the entertainment industry blacklist were evident on television, specifically at CBS. In 1957, blacklisted actor Norman Lloyd was hired by Alfred Hitchcock as an associate producer for his anthology series Alfred Hitchcock Presents, then entering its third season on the network. On November 30, 1958, a live CBS production of Wonderful Town, based on short stories written by then-Communist Ruth McKenney, appeared with the proper writing credit of blacklisted Edward Chodorov, along with his literary partner, Joseph Fields. The following year, actress Betty Hutton insisted that blacklisted composer Jerry Fielding be hired as musical director for her new series, also on CBS. The first main break in the Hollywood blacklist followed soon after. On January 20, 1960, director Otto Preminger publicly announced that Dalton Trumbo, one of the best known members of the Hollywood Ten, was the screenwriter of his forthcoming film Exodus. Six and a half months later, with Exodus still to debut, The New York Times announced that Universal Pictures would give Trumbo screen credit for his role as writer on Spartacus, a decision now recognized as being largely made by star/producer Kirk Douglas. On October 6, Spartacus premiered – the first movie to bear Trumbo's name since he had received story credit on Emergency Wedding in 1950. Since 1947, he had written or co-written approximately seventeen motion pictures without credit. Exodus followed in December, also bearing Trumbo's name. The blacklist was now clearly coming to an end, but its effects continue to reverberate even until the present.

John Henry Faulk won his lawsuit in 1962. With this court decision, the private blacklisters and those who used them were put on notice that they were legally liable for the professional and financial damage they caused. This helped to bring an end to publications such as Counterattack. Like Adrian Scott and Lillian Hellman, however, a number of those on the blacklist remained there for an extended period – Lionel Stander, for instance, could not find work in Hollywood until 1965. Some of those who named names, like Kazan and Schulberg, argued for years after that they had made an ethically proper decision. Others, like actor Lee J. Cobb and director Michael Gordon, who gave friendly testimony to HUAC after suffering on the blacklist for a time, "concede[d] with remorse that their plan was to name their way back to work". Others were haunted by the choice they had made. In 1963, actor Sterling Hayden declared,

I was a rat, a stoolie, and the names I named of those close friends were blacklisted and deprived of their livelihood.

Scholars Paul Buhle and Dave Wagner state that Hayden "was widely believed to have drunk himself into a near-suicidal depression decades before his 1986 death".

Into the 21st century, the Writers Guild pursued the correction of screen credits from movies of the 1950s and early 1960s to properly reflect the work of blacklisted writers such as Carl Foreman and Hugo Butler. On December 19, 2011, the guild, acting on a request for an investigation made by his dying son Christopher Trumbo, announced that Dalton Trumbo would get full credit for his work on the screenplay for the romantic comedy Roman Holiday (1953), almost sixty years after the fact.

Blacklisted

The Hollywood Ten

The following ten individuals were cited for contempt of Congress and blacklisted after refusing to answer questions about their alleged involvement with the Communist Party:

- Alvah Bessie, screenwriter

- Herbert Biberman, screenwriter and director

- Lester Cole, screenwriter

- Edward Dmytryk, director

- Ring Lardner Jr., screenwriter

- John Howard Lawson, screenwriter

- Albert Maltz, screenwriter

- Samuel Ornitz, screenwriter

- Adrian Scott, producer and screenwriter

- Dalton Trumbo, screenwriter

In late September 1947, HUAC subpoenaed 79 individuals on a claim that they were subversive and the supposition that they injected Communist propaganda into their films. Although never substantiating this claim, the investigators charged them with contempt of Congress when they refused to answer the questions about their membership in the Screen Writers Guild and Communist Party. The Committee demanded they admit their political beliefs and name names of other Communists. Nineteen of those refused to co-operate, and due to illnesses, scheduling conflicts, and exhaustion from the chaotic hearings, only 10 appeared before the Committee. These men became known as the Hollywood Ten.

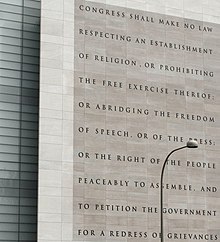

Belonging to the Communist Party did not constitute a crime, and the Committee's right to investigate these men was questionable in the first place. These men relied on the First Amendment's right to privacy, freedom of speech, and freedom of thought, but the Committee charged them with contempt of Congress for refusing to answer questions. Later defendants – except Pete Seeger – tried different strategies.

Acknowledging the potential for punishment, the Ten still took bold stands, resisting the authority of HUAC. They yelled at the Chairman and treated the Committee with open indignation, emanating negativity and discouraging outside public favor and help. Upon receiving their contempt citations, they believed the Supreme Court would overturn the rulings, which did not turn out to be the case, and as a result, they were convicted of contempt and fined $1,000 each (or, over $10,700 USD in 2016 dollars, when adjusted for inflation), and sentenced to six-months to one-year prison terms.

HUAC did not treat the Ten with respect either, refusing to allow most of them to speak for more than just a few words at a time. Meanwhile, witnesses who had arranged to co-operate with the Committee (such as the anti-Communist screenwriter Ayn Rand) were allowed to speak at length.

Martin Redish suggests that, at this time, the First Amendment's right of free expression in these cases was used to protect the powers of the government accusers instead of the rights of the citizen-victims. After witnessing the well-publicized ineffectiveness of the Ten's defense strategy, later defendants chose to plead the Fifth Amendment (against self-incrimination), instead.

Public support for the Hollywood Ten wavered, as everyday citizen-observers were never really sure what to make of them. Some of these men later wrote about their experiences as part of the Ten. John Howard Lawson, the Ten's unofficial leader, wrote a book attacking Hollywood for appeasing HUAC. While mostly criticizing the studios for their weakness, Lawson also defends himself/the Ten and criticizes Edward Dmytryk for being the only one to recant and eventually co-operate with HUAC.

In his 1981 autobiography, Hollywood Red, screenwriter Lester Cole stated that all of the Hollywood Ten had been Communist Party USA members at some point. Other members of the Hollywood Ten, such as Dalton Trumbo and Edward Dmytryk, publicly admitted to being Communists while testifying before the Committee.

When Dmytryk wrote his memoir about this period, he denounced the Ten, and defended his decision to work with HUAC. He claimed to have left the Communist Party before having been subpoenaed, defining himself as the "odd man out". He condemns the Ten's legal tactic of defiance, and regrets staying with the group for as long as he did.