The reward system (the mesocorticolimbic circuit) is a group of neural structures responsible for incentive salience (i.e., "wanting"; desire or craving for a reward and motivation), associative learning (primarily positive reinforcement and classical conditioning), and positively-valenced emotions, particularly ones involving pleasure as a core component (e.g., joy, euphoria and ecstasy).[1][2] Reward is the attractive and motivational property of a stimulus that induces appetitive behavior, also known as approach behavior, and consummatory behavior.[1] A rewarding stimulus has been described as "any stimulus, object, event, activity, or situation that has the potential to make us approach and consume it is by definition a reward".[1] In operant conditioning, rewarding stimuli function as positive reinforcers;[3] however, the converse statement also holds true: positive reinforcers are rewarding.[3]

The reward system motivates animals to approach stimuli or engage in behaviour that increases fitness (sex, energy-dense foods, etc.). Survival for most animal species depends upon maximizing contact with beneficial stimuli and minimizing contact with harmful stimuli. Reward cognition serves to increase the likelihood of survival and reproduction by causing associative learning, eliciting approach and consummatory behavior, and triggering positively-valenced emotions. Thus, reward is a mechanism that evolved to help increase the adaptive fitness of animals. In drug addiction, certain substances over-activate the reward circuit, leading to compulsive substance-seeking behavior resulting from synaptic plasticity in the circuit.

Primary rewards are a class of rewarding stimuli which facilitate the survival of one's self and offspring, and they include homeostatic (e.g., palatable food) and reproductive (e.g., sexual contact and parental investment) rewards. Intrinsic rewards are unconditioned rewards that are attractive and motivate behavior because they are inherently pleasurable. Extrinsic rewards (e.g., money or seeing one's favorite sports team winning a game) are conditioned rewards that are attractive and motivate behavior but are not inherently pleasurable. Extrinsic rewards derive their motivational value as a result of a learned association (i.e., conditioning) with intrinsic rewards. Extrinsic rewards may also elicit pleasure (e.g., euphoria from winning a lot of money in a lottery) after being classically conditioned with intrinsic rewards.

Definition

In neuroscience, the reward system is a collection of brain structures and neural pathways that are responsible for reward-related cognition, including associative learning (primarily classical conditioning and operant reinforcement), incentive salience (i.e., motivation and "wanting", desire, or craving for a reward), and positively-valenced emotions, particularly emotions that involve pleasure (i.e., hedonic "liking").

Terms that are commonly used to describe behavior related to the "wanting" or desire component of reward include appetitive behavior, approach behavior, preparatory behavior, instrumental behavior, anticipatory behavior, and seeking. Terms that are commonly used to describe behavior related to the "liking" or pleasure component of reward include consummatory behavior and taking behavior.

The three primary functions of rewards are their capacity to:

- produce associative learning (i.e., classical conditioning and operant reinforcement);

- affect decision-making and induce approach behavior (via the assignment of motivational salience to rewarding stimuli);

- elicit positively-valenced emotions, particularly pleasure.

Neuroanatomy

Overview

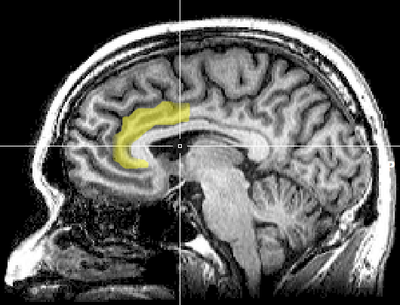

The brain structures that compose the reward system are located primarily within the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loop; the basal ganglia portion of the loop drives activity within the reward system. Most of the pathways that connect structures within the reward system are glutamatergic interneurons, GABAergic medium spiny neurons (MSNs), and dopaminergic projection neurons, although other types of projection neurons contribute (e.g., orexinergic projection neurons). The reward system includes the ventral tegmental area, ventral striatum (i.e., the nucleus accumbens and olfactory tubercle), dorsal striatum (i.e., the caudate nucleus and putamen), substantia nigra (i.e., the pars compacta and pars reticulata), prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, insular cortex, hippocampus, hypothalamus (particularly, the orexinergic nucleus in the lateral hypothalamus), thalamus (multiple nuclei), subthalamic nucleus, globus pallidus (both external and internal), ventral pallidum, parabrachial nucleus, amygdala, and the remainder of the extended amygdala. The dorsal raphe nucleus and cerebellum appear to modulate some forms of reward-related cognition (i.e., associative learning, motivational salience, and positive emotions) and behaviors as well. The laterodorsal tegmental nucleus (LTD), pedunculopontine nucleus (PPTg), and lateral habenula (LHb) (both directly and indirectly via the rostromedial tegmental nucleus) are also capable of inducing aversive salience and incentive salience through their projections to the ventral tegmental area (VTA). The LDT and PPTg both send glutaminergic projections to the VTA that synapse on dopaminergic neurons, both of which can produce incentive salience. The LHb sends glutaminergic projections, the majority of which synapse on GABAergic RMTg neurons that in turn drive inhibition of dopaminergic VTA neurons, although some LHb projections terminate on VTA interneurons. These LHb projections are activated both by aversive stimuli and by the absence of an expected reward, and excitation of the LHb can induce aversion.

Most of the dopamine pathways (i.e., neurons that use the neurotransmitter dopamine to communicate with other neurons) that project out of the ventral tegmental area are part of the reward system; in these pathways, dopamine acts on D1-like receptors or D2-like receptors to either stimulate (D1-like) or inhibit (D2-like) the production of cAMP. The GABAergic medium spiny neurons of the striatum are components of the reward system as well. The glutamatergic projection nuclei in the subthalamic nucleus, prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, and amygdala connect to other parts of the reward system via glutamate pathways. The medial forebrain bundle, which is a set of many neural pathways that mediate brain stimulation reward (i.e., reward derived from direct electrochemical stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus), is also a component of the reward system.

Two theories exist with regard to the activity of the nucleus accumbens and the generation liking and wanting. The inhibition (or hyperpolarization) hypothesis proposes that the nucleus accumbens exerts tonic inhibitory effects on downstream structures such as the ventral pallidum, hypothalamus or ventral tegmental area, and that in inhibiting MSNs in the nucleus accumbens (NAcc), these structures are excited, "releasing" reward related behavior. While GABA receptor agonists are capable of eliciting both "liking" and "wanting" reactions in the nucleus accumbens, glutaminergic inputs from the basolateral amygdala, ventral hippocampus, and medial prefrontal cortex can drive incentive salience. Furthermore, while most studies find that NAcc neurons reduce firing in response to reward, a number of studies find the opposite response. This had led to the proposal of the disinhibition (or depolarization) hypothesis, that proposes that excitation or NAcc neurons, or at least certain subsets, drives reward related behavior.

After nearly 50 years of research on brain-stimulation reward, experts have certified that dozens of sites in the brain will maintain intracranial self-stimulation. Regions include the lateral hypothalamus and medial forebrain bundles, which are especially effective. Stimulation there activates fibers that form the ascending pathways; the ascending pathways include the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, which projects from the ventral tegmental area to the nucleus accumbens. There are several explanations as to why the mesolimbic dopamine pathway is central to circuits mediating reward. First, there is a marked increase in dopamine release from the mesolimbic pathway when animals engage in intracranial self-stimulation. Second, experiments consistently indicate that brain-stimulation reward stimulates the reinforcement of pathways that are normally activated by natural rewards, and drug reward or intracranial self-stimulation can exert more powerful activation of central reward mechanisms because they activate the reward center directly rather than through the peripheral nerves. Third, when animals are administered addictive drugs or engage in naturally rewarding behaviors, such as feeding or sexual activity, there is a marked release of dopamine within the nucleus accumbens. However, dopamine is not the only reward compound in the brain.

Key pathway

Ventral tegmental area

- The ventral tegmental area (VTA) is important in responding to stimuli and cues that indicate a reward is present. Rewarding stimuli (and all addictive drugs) act on the circuit by triggering the VTA to release dopamine signals to the nucleus accumbens, either directly or indirectly. The VTA has two important pathways: The mesolimbic pathway projecting to limbic (striatal) regions and underpinning the motivational behaviors and processes, and the mesocortical pathway projecting to the prefrontal cortex, underpinning cognitive functions, such as learning external cues, etc.

- Dopaminergic neurons in this region converts the amino acid tyrosine into DOPA using the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase, which is then converted to dopamine using the enzyme dopa-decarboxylase.

Striatum (Nucleus Accumbens)

- The striatum is broadly involved in acquiring and eliciting learned behaviors in response to a rewarding cue. The VTA projects to the striatum, and activates the GABA-ergic Medium Spiny Neurons via D1 and D2 receptors within the ventral (Nucleus Accumbens) and dorsal striatum.

- The Ventral Striatum (the Nucleus Accumbens) is broadly involved in acquiring behavior when fed into by the VTA, and eliciting behavior when fed into by the PFC. The NAc shell projects to the pallidum and the VTA, regulating limbic and autonomic functions. This modulates the reinforcing properties of stimuli, and short term aspects of reward. The NAc Core projects to the substantia nigra and is involved in the development of reward-seeking behaviors and its expression. It is involved in spatial learning, conditional response, and impulsive choice; the long term elements of reward.

- The Dorsal Striatum is involved in learning, the Dorsal Medial Striatum in goal directed learning, and the Dorsal Lateral Striatum in stimulus-response learning foundational to Pavlovian response. On repeated activation by a stimuli, the Nucleus Accumbens can activate the Dorsal Striatum via an intrastriatal loop. The transition of signals from the NAc to the DS allows reward associated cues to activate the DS without the reward itself being present. This can activate cravings and reward-seeking behaviors (and is responsible for triggering relapse during abstinence in addiction).

Prefrontal Cortex

- The VTA dopaminergic neurons project to the PFC, activating glutaminergic neurons that project to multiple other regions, including the Dorsal Striatum and NAc, ultimately allowing the PFC to mediate salience and conditional behaviors in response to stimuli.

- Notably, abstinence from addicting drugs activates the PFC, glutamatergic projection to the NAc, which leads to strong cravings, and modulates reinstatement of addiction behaviors resulting from abstinence. The PFC also interacts with the VTA through the mesocortical pathway, and helps associate environmental cues with the reward.

Hippocampus

- The Hippocampus has multiple functions, including in the creation and storage of memories . In the reward circuit, it serves to contextual memories and associated cues. It ultimately underpins the reinstatement of reward-seeking behaviors via cues, and contextual triggers.

Amygdala

- The AMY receives input from the VTA, and outputs to the NAc. The amygdala is important in creating powerful emotional flashbulb memories, and likely underpins the creation of strong cue-associated memories. It also is important in mediating the anxiety effects of withdrawal, and increased drug intake in addiction.

Pleasure centers

Pleasure is a component of reward, but not all rewards are pleasurable (e.g., money does not elicit pleasure unless this response is conditioned). Stimuli that are naturally pleasurable, and therefore attractive, are known as intrinsic rewards, whereas stimuli that are attractive and motivate approach behavior, but are not inherently pleasurable, are termed extrinsic rewards. Extrinsic rewards (e.g., money) are rewarding as a result of a learned association with an intrinsic reward. In other words, extrinsic rewards function as motivational magnets that elicit "wanting", but not "liking" reactions once they have been acquired.

The reward system contains pleasure centers or hedonic hotspots – i.e., brain structures that mediate pleasure or "liking" reactions from intrinsic rewards. As of October 2017, hedonic hotspots have been identified in subcompartments within the nucleus accumbens shell, ventral pallidum, parabrachial nucleus, orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), and insular cortex. The hotspot within the nucleus accumbens shell is located in the rostrodorsal quadrant of the medial shell, while the hedonic coldspot is located in a more posterior region. The posterior ventral pallidum also contains a hedonic hotspot, while the anterior ventral pallidum contains a hedonic coldspot. Microinjections of opioids, endocannabinoids, and orexin are capable of enhancing liking in these hotspots. The hedonic hotspots located in the anterior OFC and posterior insula have been demonstrated to respond to orexin and opioids, as has the overlapping hedonic coldspot in the anterior insula and posterior OFC. On the other hand, the parabrachial nucleus hotspot has only been demonstrated to respond to benzodiazepine receptor agonists.

Hedonic hotspots are functionally linked, in that activation of one hotspot results in the recruitment of the others, as indexed by the induced expression of c-Fos, an immediate early gene. Furthermore, inhibition of one hotspot results in the blunting of the effects of activating another hotspot.Therefore, the simultaneous activation of every hedonic hotspot within the reward system is believed to be necessary for generating the sensation of an intense euphoria.

Wanting and liking

Incentive salience is the "wanting" or "desire" attribute, which includes a motivational component, that is assigned to a rewarding stimulus by the nucleus accumbens shell (NAcc shell). The degree of dopamine neurotransmission into the NAcc shell from the mesolimbic pathway is highly correlated with the magnitude of incentive salience for rewarding stimuli.

Activation of the dorsorostral region of the nucleus accumbens correlates with increases in wanting without concurrent increases in liking. However, dopaminergic neurotransmission into the nucleus accumbens shell is responsible not only for appetitive motivational salience (i.e., incentive salience) towards rewarding stimuli, but also for aversive motivational salience, which directs behavior away from undesirable stimuli. In the dorsal striatum, activation of D1 expressing MSNs produces appetitive incentive salience, while activation of D2 expressing MSNs produces aversion. In the NAcc, such a dichotomy is not as clear cut, and activation of both D1 and D2 MSNs is sufficient to enhance motivation, likely via disinhibiting the VTA through inhibiting the ventral pallidum.

Robinson and Berridge's 1993 incentive-sensitization theory proposed that reward contains separable psychological components: wanting (incentive) and liking (pleasure). To explain increasing contact with a certain stimulus such as chocolate, there are two independent factors at work – our desire to have the chocolate (wanting) and the pleasure effect of the chocolate (liking). According to Robinson and Berridge, wanting and liking are two aspects of the same process, so rewards are usually wanted and liked to the same degree. However, wanting and liking also change independently under certain circumstances. For example, rats that do not eat after receiving dopamine (experiencing a loss of desire for food) act as though they still like food. In another example, activated self-stimulation electrodes in the lateral hypothalamus of rats increase appetite, but also cause more adverse reactions to tastes such as sugar and salt; apparently, the stimulation increases wanting but not liking. Such results demonstrate that the reward system of rats includes independent processes of wanting and liking. The wanting component is thought to be controlled by dopaminergic pathways, whereas the liking component is thought to be controlled by opiate-benzodiazepine systems.

Anti-reward system

Koobs & Le Moal proposed that there exists a separate circuit responsible for the attenuation of reward-pursuing behavior, which they termed the anti-reward circuit. This component acts as brakes on the reward circuit, thus preventing the over pursuit of food, sex, etc. This circuit involves multiple parts of the amygdala (the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, the central nucleus), the Nucleus Accumbens, and signal molecules including norepinephrine, corticotropin-releasing factor, and dynorphin. This circuit is also hypothesized to mediate the unpleasant components of stress, and is thus thought to be involved in addiction and withdrawal. While the reward circuit mediates the initial positive reinforcement involved in the development of addiction, it is the anti-reward circuit that later dominates via negative reinforcement that motivates the pursuit of the rewarding stimuli.

Learning

Rewarding stimuli can drive learning in both the form of classical conditioning (Pavlovian conditioning) and operant conditioning (instrumental conditioning). In classical conditioning, a reward can act as an unconditioned stimulus that, when associated with the conditioned stimulus, causes the conditioned stimulus to elicit both musculoskeletal (in the form of simple approach and avoidance behaviors) and vegetative responses. In operant conditioning, a reward may act as a reinforcer in that it increases or supports actions that lead to itself. Learned behaviors may or may not be sensitive to the value of the outcomes they lead to; behaviors that are sensitive to the contingency of an outcome on the performance of an action as well as the outcome value are goal-directed, while elicited actions that are insensitive to contingency or value are called habits. This distinction is thought to reflected two forms of learning, model free and model based. Model free learning involves the simple caching and updating of values. In contrast, model based learning involves the storage and construction of an internal model of events that allows inference and flexible prediction. Although pavlovian conditioning is generally assumed to be model-free, the incentive salience assigned to a conditioned stimulus is flexible with regard to changes in internal motivational states.

Distinct neural systems are responsible for learning associations between stimuli and outcomes, actions and outcomes, and stimuli and responses. Although classical conditioning is not limited to the reward system, the enhancement of instrumental performance by stimuli (i.e., Pavlovian-instrumental transfer) requires the nucleus accumbens. Habitual and goal directed instrumental learning are dependent upon the lateral striatum and the medial striatum, respectively.

During instrumental learning, opposing changes in the ratio of AMPA to NMDA receptors and phosphorylated ERK occurs in the D1-type and D2-type MSNs that constitute the direct and indirect pathways, respectively. These changes in synaptic plasticity and the accompanying learning is dependent upon activation of striatal D1 and NMDA receptors. The intracellular cascade activated by D1 receptors involves the recruitment of protein kinase A, and through resulting phosphorylation of DARPP-32, the inhibition of phosphatases that deactivate ERK. NMDA receptors activate ERK through a different but interrelated Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway. Alone NMDA mediated activation of ERK is self-limited, as NMDA activation also inhibits PKA mediated inhibition of ERK deactivating phosphatases. However, when D1 and NMDA cascades are co-activated, they work synergistically, and the resultant activation of ERK regulates synaptic plasticity in the form of spine restructuring, transport of AMPA receptors, regulation of CREB, and increasing cellular excitability via inhibiting Kv4.2

Disorders

Addiction

ΔFosB (DeltaFosB) – a gene transcription factor – overexpression in the D1-type medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens is the crucial common factor among virtually all forms of addiction (i.e., behavioral addictions and drug addictions) that induces addiction-related behavior and neural plasticity. In particular, ΔFosB promotes self-administration, reward sensitization, and reward cross-sensitization effects among specific addictive drugs and behaviors. Certain epigenetic modifications of histone protein tails (i.e., histone modifications) in specific regions of the brain are also known to play a crucial role in the molecular basis of addictions.

Addictive drugs and behaviors are rewarding and reinforcing (i.e., are addictive) due to their effects on the dopamine reward pathway.

The lateral hypothalamus and medial forebrain bundle has been the most-frequently-studied brain-stimulation reward site, particularly in studies of the effects of drugs on brain stimulation reward. The neurotransmitter system that has been most-clearly identified with the habit-forming actions of drugs-of-abuse is the mesolimbic dopamine system, with its efferent targets in the nucleus accumbens and its local GABAergic afferents. The reward-relevant actions of amphetamine and cocaine are in the dopaminergic synapses of the nucleus accumbens and perhaps the medial prefrontal cortex. Rats also learn to lever-press for cocaine injections into the medial prefrontal cortex, which works by increasing dopamine turnover in the nucleus accumbens. Nicotine infused directly into the nucleus accumbens also enhances local dopamine release, presumably by a presynaptic action on the dopaminergic terminals of this region. Nicotinic receptors localize to dopaminergic cell bodies and local nicotine injections increase dopaminergic cell firing that is critical for nicotinic reward. Some additional habit-forming drugs are also likely to decrease the output of medium spiny neurons as a consequence, despite activating dopaminergic projections. For opiates, the lowest-threshold site for reward effects involves actions on GABAergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area, a secondary site of opiate-rewarding actions on medium spiny output neurons of the nucleus accumbens. Thus the following form the core of currently characterised drug-reward circuitry; GABAergic afferents to the mesolimbic dopamine neurons (primary substrate of opiate reward), the mesolimbic dopamine neurons themselves (primary substrate of psychomotor stimulant reward), and GABAergic efferents to the mesolimbic dopamine neurons (a secondary site of opiate reward).

Motivation

Dysfunctional motivational salience appears in a number of psychiatric symptoms and disorders. Anhedonia, traditionally defined as a reduced capacity to feel pleasure, has been re-examined as reflecting blunted incentive salience, as most anhedonic populations exhibit intact “liking”. On the other end of the spectrum, heightened incentive salience that is narrowed for specific stimuli is characteristic of behavioral and drug addictions. In the case of fear or paranoia, dysfunction may lie in elevated aversive salience.

Neuroimaging studies across diagnoses associated with anhedonia have reported reduced activity in the OFC and ventral striatum. One meta analysis reported anhedonia was associated with reduced neural response to reward anticipation in the caudate nucleus, putamen, nucleus accumbens and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC).

Mood disorders

Certain types of depression are associated with reduced motivation, as assessed by willingness to expend effort for reward. These abnormalities have been tentatively linked to reduced activity in areas of the striatum, and while dopaminergic abnormalities are hypothesized to play a role, most studies probing dopamine function in depression have reported inconsistent results. Although postmortem and neuroimaging studies have found abnormalities in numerous regions of the reward system, few findings are consistently replicated. Some studies have reported reduced NAcc, hippocampus, medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) activity, as well as elevated basolateral amygdala and subgenual cingulate cortex (sgACC) activity during tasks related to reward or positive stimuli. These neuroimaging abnormalities are complemented by little post mortem research, but what little research has been done suggests reduced excitatory synapses in the mPFC. Reduced activity in the mPFC during reward related tasks appears to be localized to more dorsal regions(i.e. the pregenual cingulate cortex), while the more ventral sgACC is hyperactive in depression.

Attempts to investigate underlying neural circuitry in animal models has also yielded conflicting results. Two paradigms are commonly used to simulate depression, chronic social defeat (CSDS), and chronic mild stress (CMS), although many exist. CSDS produces reduced preference for sucrose, reduced social interactions, and increased immobility in the forced swim test. CMS similarly reduces sucrose preference, and behavioral despair as assessed by tail suspension and forced swim tests. Animals susceptible to CSDS exhibit increased phasic VTA firing, and inhibition of VTA-NAcc projections attenuates behavioral deficits induced by CSDS. However, inhibition of VTA-mPFC projections exacerbates social withdrawal. On the other hand, CMS associated reductions in sucrose preference and immobility were attenuated and exacerbated by VTA excitation and inhibition, respectively. Although these differences may be attributable to different stimulation protocols or poor translational paradigms, variable results may also lie in the heterogenous functionality of reward related regions.

Optogenetic stimulation of the mPFC as a whole produces antidepressant effects. This effect appears localized to the rodent homologue of the pgACC (the prelimbic cortex), as stimulation of the rodent homologue of the sgACC (the infralimbic cortex) produces no behavioral effects. Furthermore, deep brain stimulation in the infralimbic cortex, which is thought to have an inhibitory effect, also produces an antidepressant effect. This finding is congruent with the observation that pharmacological inhibition of the infralimbic cortex attenuates depressive behaviors.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is associated with deficits in motivation, commonly grouped under other negative symptoms such as reduced spontaneous speech. The experience of “liking” is frequently reported to be intact, both behaviorally and neurally, although results may be specific to certain stimuli, such as monetary rewards. Furthermore, implicit learning and simple reward-related tasks are also intact in schizophrenia. Rather, deficits in the reward system are apparent during reward-related tasks that are cognitively complex. These deficits are associated with both abnormal striatal and OFC activity, as well as abnormalities in regions associated with cognitive functions such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC).

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

In those with ADHD, core aspects of the reward system are underactive, making it challenging to derive reward from regular activities. Those with the disorder experience a boost of motivation after a high-stimulation behaviour triggers a release of dopamine. In the aftermath of that boost and reward, the return to baseline levels results in an immediate drop in motivation.

Impairments of dopaminergic and serotonergic function are said to be key factors in ADHD. These impairments can lead to executive dysfunction such as dysregulation of reward processing and motivational dysfunction, including anhedonia.

History

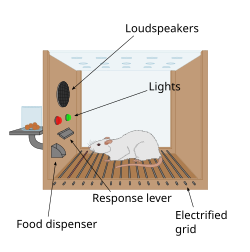

The first clue to the presence of a reward system in the brain came with an accident discovery by James Olds and Peter Milner in 1954. They discovered that rats would perform behaviors such as pressing a bar, to administer a brief burst of electrical stimulation to specific sites in their brains. This phenomenon is called intracranial self-stimulation or brain stimulation reward. Typically, rats will press a lever hundreds or thousands of times per hour to obtain this brain stimulation, stopping only when they are exhausted. While trying to teach rats how to solve problems and run mazes, stimulation of certain regions of the brain where the stimulation was found seemed to give pleasure to the animals. They tried the same thing with humans and the results were similar. The explanation to why animals engage in a behavior that has no value to the survival of either themselves or their species is that the brain stimulation is activating the system underlying reward.

In a fundamental discovery made in 1954, researchers James Olds and Peter Milner found that low-voltage electrical stimulation of certain regions of the brain of the rat acted as a reward in teaching the animals to run mazes and solve problems. It seemed that stimulation of those parts of the brain gave the animals pleasure, and in later work humans reported pleasurable sensations from such stimulation. When rats were tested in Skinner boxes where they could stimulate the reward system by pressing a lever, the rats pressed for hours. Research in the next two decades established that dopamine is one of the main chemicals aiding neural signaling in these regions, and dopamine was suggested to be the brain's "pleasure chemical".

Ivan Pavlov was a psychologist who used the reward system to study classical conditioning. Pavlov used the reward system by rewarding dogs with food after they had heard a bell or another stimulus. Pavlov was rewarding the dogs so that the dogs associated food, the reward, with the bell, the stimulus. Edward L. Thorndike used the reward system to study operant conditioning. He began by putting cats in a puzzle box and placing food outside of the box so that the cat wanted to escape. The cats worked to get out of the puzzle box to get to the food. Although the cats ate the food after they escaped the box, Thorndike learned that the cats attempted to escape the box without the reward of food. Thorndike used the rewards of food and freedom to stimulate the reward system of the cats. Thorndike used this to see how the cats learned to escape the box.

Other species

Animals quickly learn to press a bar to obtain an injection of opiates directly into the midbrain tegmentum or the nucleus accumbens. The same animals do not work to obtain the opiates if the dopaminergic neurons of the mesolimbic pathway are inactivated. In this perspective, animals, like humans, engage in behaviors that increase dopamine release.

Kent Berridge, a researcher in affective neuroscience, found that sweet (liked ) and bitter (disliked ) tastes produced distinct orofacial expressions, and these expressions were similarly displayed by human newborns, orangutans, and rats. This was evidence that pleasure (specifically, liking) has objective features and was essentially the same across various animal species. Most neuroscience studies have shown that the more dopamine released by the reward, the more effective the reward is. This is called the hedonic impact, which can be changed by the effort for the reward and the reward itself. Berridge discovered that blocking dopamine systems did not seem to change the positive reaction to something sweet (as measured by facial expression). In other words, the hedonic impact did not change based on the amount of sugar. This discounted the conventional assumption that dopamine mediates pleasure. Even with more-intense dopamine alterations, the data seemed to remain constant. However, a clinical study from January 2019 that assessed the effect of a dopamine precursor (levodopa), antagonist (risperidone), and a placebo on reward responses to music – including the degree of pleasure experienced during musical chills, as measured by changes in electrodermal activity as well as subjective ratings – found that the manipulation of dopamine neurotransmission bidirectionally regulates pleasure cognition (specifically, the hedonic impact of music) in human subjects. This research demonstrated that increased dopamine neurotransmission acts as a sine qua non condition for pleasurable hedonic reactions to music in humans.

Berridge developed the incentive salience hypothesis to address the wanting aspect of rewards. It explains the compulsive use of drugs by drug addicts even when the drug no longer produces euphoria, and the cravings experienced even after the individual has finished going through withdrawal. Some addicts respond to certain stimuli involving neural changes caused by drugs. This sensitization in the brain is similar to the effect of dopamine because wanting and liking reactions occur. Human and animal brains and behaviors experience similar changes regarding reward systems because these systems are so prominent.