Consequentialism is a class of normative, teleological ethical theories that holds that the consequences of one's conduct are the ultimate basis for judgment about the rightness or wrongness of that conduct. Thus, from a consequentialist standpoint, a morally right act (or omission from acting) is one that will produce a good outcome. Consequentialism, along with eudaimonism, falls under the broader category of teleological ethics, a group of views which claim that the moral value of any act consists in its tendency to produce things of intrinsic value. Consequentialists hold in general that an act is right if and only if the act (or in some views, the rule under which it falls) will produce, will probably produce, or is intended to produce, a greater balance of good over evil than any available alternative. Different consequentialist theories differ in how they define moral goods, with chief candidates including pleasure, the absence of pain, the satisfaction of one's preferences, and broader notions of the "general good".

Consequentialism is usually contrasted with deontological ethics (or deontology), in that deontology, in which rules and moral duty are central, derives the rightness or wrongness of one's conduct from the character of the behaviour itself rather than the outcomes of the conduct. It is also contrasted with virtue ethics, which focuses on the character of the agent rather than on the nature or consequences of the act (or omission) itself, and pragmatic ethics which treats morality like science: advancing socially over the course of many lifetimes, such that any moral criterion is subject to revision.

Some argue that consequentialist theories (such as utilitarianism) and deontological theories (such as Kantian ethics) are not necessarily mutually exclusive. For example, T. M. Scanlon advances the idea that human rights, which are commonly considered a "deontological" concept, can only be justified with reference to the consequences of having those rights. Similarly, Robert Nozick argued for a theory that is mostly consequentialist, but incorporates inviolable "side-constraints" which restrict the sort of actions agents are permitted to do. Derek Parfit argued that in practice, when understood properly, rule consequentialism, Kantian deontology and contractualism would all end up prescribing the same behavior.

Forms of consequentialism

Utilitarianism

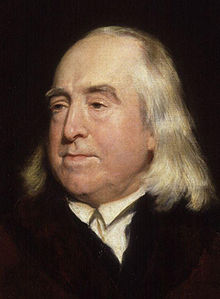

Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do. On the one hand the standard of right and wrong, on the other the chain of causes and effects, are fastened to their throne. They govern us in all we do, in all we say, in all we think...

— Jeremy Bentham, The Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789) Ch I, p 1

In summary, Jeremy Bentham states that people are driven by their interests and their fears, but their interests take precedence over their fears; their interests are carried out in accordance with how people view the consequences that might be involved with their interests. Happiness, in this account, is defined as the maximization of pleasure and the minimization of pain. It can be argued that the existence of phenomenal consciousness and "qualia" is required for the experience of pleasure or pain to have an ethical significance.

Historically, hedonistic utilitarianism is the paradigmatic example of a consequentialist moral theory. This form of utilitarianism holds that what matters is the aggregate happiness; the happiness of everyone, and not the happiness of any particular person. John Stuart Mill, in his exposition of hedonistic utilitarianism, proposed a hierarchy of pleasures, meaning that the pursuit of certain kinds of pleasure is more highly valued than the pursuit of other pleasures. However, some contemporary utilitarians, such as Peter Singer, are concerned with maximizing the satisfaction of preferences, hence preference utilitarianism. Other contemporary forms of utilitarianism mirror the forms of consequentialism outlined below.

Rule consequentialism

In general, consequentialist theories focus on actions. However, this need not be the case. Rule consequentialism is a theory that is sometimes seen as an attempt to reconcile consequentialism with deontology, or rules-based ethics—and in some cases, this is stated as a criticism of rule consequentialism. Like deontology, rule consequentialism holds that moral behavior involves following certain rules. However, rule consequentialism chooses rules based on the consequences that the selection of those rules has. Rule consequentialism exists in the forms of rule utilitarianism and rule egoism.

Various theorists are split as to whether the rules are the only determinant of moral behavior or not. For example, Robert Nozick held that a certain set of minimal rules, which he calls "side-constraints," are necessary to ensure appropriate actions. There are also differences as to how absolute these moral rules are. Thus, while Nozick's side-constraints are absolute restrictions on behavior, Amartya Sen proposes a theory that recognizes the importance of certain rules, but these rules are not absolute. That is, they may be violated if strict adherence to the rule would lead to much more undesirable consequences.

One of the most common objections to rule-consequentialism is that it is incoherent, because it is based on the consequentialist principle that what we should be concerned with is maximizing the good, but then it tells us not to act to maximize the good, but to follow rules (even in cases where we know that breaking the rule could produce better results).

In Ideal Code, Real World, Brad Hooker avoids this objection by not basing his form of rule-consequentialism on the ideal of maximizing the good. He writes:

[T]he best argument for rule-consequentialism is not that it derives from an overarching commitment to maximise the good. The best argument for rule-consequentialism is that it does a better job than its rivals of matching and tying together our moral convictions, as well as offering us help with our moral disagreements and uncertainties.

Derek Parfit described Hooker's book as the "best statement and defence, so far, of one of the most important moral theories."

State consequentialism

It is the business of the benevolent man to seek to promote what is beneficial to the world and to eliminate what is harmful, and to provide a model for the world. What benefits he will carry out; what does not benefit men he will leave alone.

— Mozi, Mozi (5th century BC) Part I

State consequentialism, also known as Mohist consequentialism, is an ethical theory that evaluates the moral worth of an action based on how much it contributes to the welfare of a state. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Mohist consequentialism, dating back to the 5th century BCE, is the "world's earliest form of consequentialism, a remarkably sophisticated version based on a plurality of intrinsic goods taken as constitutive of human welfare."

Unlike utilitarianism, which views utility as the sole moral good, "the basic goods in Mohist consequentialist thinking are...order, material wealth, and increase in population." During the time of Mozi, war and famine were common, and population growth was seen as a moral necessity for a harmonious society. The "material wealth" of Mohist consequentialism refers to basic needs, like shelter and clothing; and "order" refers to Mozi's stance against warfare and violence, which he viewed as pointless and a threat to social stability. In The Cambridge History of Ancient China, Stanford sinologist David Shepherd Nivison writes that the moral goods of Mohism "are interrelated: more basic wealth, then more reproduction; more people, then more production and wealth...if people have plenty, they would be good, filial, kind, and so on unproblematically."

The Mohists believed that morality is based on "promoting the benefit of all under heaven and eliminating harm to all under heaven." In contrast to Jeremy Bentham's views, state consequentialism is not utilitarian because it is not hedonistic or individualistic. The importance of outcomes that are good for the community outweigh the importance of individual pleasure and pain. The term state consequentialism has also been applied to the political philosophy of the Confucian philosopher Xunzi. On the other hand, "legalist" Han Fei "is motivated almost totally from the ruler's point of view."

Ethical egoism

Ethical egoism can be understood as a consequentialist theory according to which the consequences for the individual agent are taken to matter more than any other result. Thus, egoism will prescribe actions that may be beneficial, detrimental, or neutral to the welfare of others. Some, like Henry Sidgwick, argue that a certain degree of egoism promotes the general welfare of society for two reasons: because individuals know how to please themselves best, and because if everyone were an austere altruist then general welfare would inevitably decrease.

Ethical altruism

Ethical altruism can be seen as a consequentialist theory which prescribes that an individual take actions that have the best consequences for everyone except for himself. This was advocated by Auguste Comte, who coined the term altruism, and whose ethics can be summed up in the phrase "Live for others."

Two-level consequentialism

The two-level approach involves engaging in critical reasoning and considering all the possible ramifications of one's actions before making an ethical decision, but reverting to generally reliable moral rules when one is not in a position to stand back and examine the dilemma as a whole. In practice, this equates to adhering to rule consequentialism when one can only reason on an intuitive level, and to act consequentialism when in a position to stand back and reason on a more critical level.

This position can be described as a reconciliation between act consequentialism—in which the morality of an action is determined by that action's effects—and rule consequentialism—in which moral behavior is derived from following rules that lead to positive outcomes.

The two-level approach to consequentialism is most often associated with R. M. Hare and Peter Singer.

Motive consequentialism

Another consequentialist version is motive consequentialism, which looks at whether the state of affairs that results from the motive to choose an action is better or at least as good as each of the alternative state of affairs that would have resulted from alternative actions. This version gives relevance to the motive of an act and links it to its consequences. An act can therefore not be wrong if the decision to act was based on a right motive. A possible inference is, that one can not be blamed for mistaken judgments if the motivation was to do good.

Negative consequentialism

Most consequentialist theories focus on promoting some sort of good consequences. However, negative utilitarianism lays out a consequentialist theory that focuses solely on minimizing bad consequences.

One major difference between these two approaches is the agent's responsibility. Positive consequentialism demands that we bring about good states of affairs, whereas negative consequentialism requires that we avoid bad ones. Stronger versions of negative consequentialism will require active intervention to prevent bad and ameliorate existing harm. In weaker versions, simple forbearance from acts tending to harm others is sufficient. An example of this is the slippery-slope argument, which encourages others to avoid a specified act on the grounds that it may ultimately lead to undesirable consequences.

Often "negative" consequentialist theories assert that reducing suffering is more important than increasing pleasure. Karl Popper, for example, claimed that "from the moral point of view, pain cannot be outweighed by pleasure." (While Popper is not a consequentialist per se, this is taken as a classic statement of negative utilitarianism.) When considering a theory of justice, negative consequentialists may use a statewide or global-reaching principle: the reduction of suffering (for the disadvantaged) is more valuable than increased pleasure (for the affluent or luxurious).

Acts and omissions

Since pure consequentialism holds that an action is to be judged solely by its result, most consequentialist theories hold that a deliberate action is no different from a deliberate decision not to act. This contrasts with the "acts and omissions doctrine", which is upheld by some medical ethicists and some religions: it asserts there is a significant moral distinction between acts and deliberate non-actions which lead to the same outcome. This contrast is brought out in issues such as voluntary euthanasia.

Actualism and possibilism

The normative status of an action depends on its consequences according to consequentialism. The consequences of the actions of an agent may include other actions by this agent. Actualism and possibilism disagree on how later possible actions impact the normative status of the current action by the same agent. Actualists assert that it is only relevant what the agent would actually do later for assessing the value of an alternative. Possibilists, on the other hand, hold that we should also take into account what the agent could do, even if she wouldn't do it.

For example, assume that Gifre has the choice between two alternatives, eating a cookie or not eating anything. Having eaten the first cookie, Gifre could stop eating cookies, which is the best alternative. But after having tasted one cookie, Gifre would freely decide to continue eating cookies until the whole bag is finished, which would result in a terrible stomach ache and would be the worst alternative. Not eating any cookies at all, on the other hand, would be the second-best alternative. Now the question is: should Gifre eat the first cookie or not? Actualists are only concerned with the actual consequences. According to them, Gifre should not eat any cookies at all since it is better than the alternative leading to a stomach ache. Possibilists, however, contend that the best possible course of action involves eating the first cookie and this is therefore what Gifre should do.

One counterintuitive consequence of actualism is that agents can avoid moral obligations simply by having an imperfect moral character. For example, a lazy person might justify rejecting a request to help a friend by arguing that, due to her lazy character, she wouldn't have done the work anyway, even if she had accepted the request. By rejecting the offer right away, she managed at least not to waste anyone's time. Actualists might even consider her behavior praiseworthy since she did what, according to actualism, she ought to have done. This seems to be a very easy way to "get off the hook" that is avoided by possibilism. But possibilism has to face the objection that in some cases it sanctions and even recommends what actually leads to the worst outcome.

Douglas W. Portmore has suggested that these and other problems of actualism and possibilism can be avoided by constraining what counts as a genuine alternative for the agent. On his view, it is a requirement that the agent has rational control over the event in question. For example, eating only one cookie and stopping afterward only is an option for Gifre if she has the rational capacity to repress her temptation to continue eating. If the temptation is irrepressible then this course of action is not considered to be an option and is therefore not relevant when assessing what the best alternative is. Portmore suggests that, given this adjustment, we should prefer a view very closely associated with possibilism called maximalism.

Issues

Action guidance

One important characteristic of many normative moral theories such as consequentialism is the ability to produce practical moral judgements. At the very least, any moral theory needs to define the standpoint from which the goodness of the consequences are to be determined. What is primarily at stake here is the responsibility of the agent.

The ideal observer

One common tactic among consequentialists, particularly those committed to an altruistic (selfless) account of consequentialism, is to employ an ideal, neutral observer from which moral judgements can be made. John Rawls, a critic of utilitarianism, argues that utilitarianism, in common with other forms of consequentialism, relies on the perspective of such an ideal observer. The particular characteristics of this ideal observer can vary from an omniscient observer, who would grasp all the consequences of any action, to an ideally informed observer, who knows as much as could reasonably be expected, but not necessarily all the circumstances or all the possible consequences. Consequentialist theories that adopt this paradigm hold that right action is the action that will bring about the best consequences from this ideal observer's perspective.

The real observer

In practice, it is very difficult, and at times arguably impossible, to adopt the point of view of an ideal observer. Individual moral agents do not know everything about their particular situations, and thus do not know all the possible consequences of their potential actions. For this reason, some theorists have argued that consequentialist theories can only require agents to choose the best action in line with what they know about the situation. However, if this approach is naïvely adopted, then moral agents who, for example, recklessly fail to reflect on their situation, and act in a way that brings about terrible results, could be said to be acting in a morally justifiable way. Acting in a situation without first informing oneself of the circumstances of the situation can lead to even the most well-intended actions yielding miserable consequences. As a result, it could be argued that there is a moral imperative for an agent to inform himself as much as possible about a situation before judging the appropriate course of action. This imperative, of course, is derived from consequential thinking: a better-informed agent is able to bring about better consequences.

Consequences for whom

Moral action always has consequences for certain people or things. Varieties of consequentialism can be differentiated by the beneficiary of the good consequences. That is, one might ask "Consequences for whom?"

Agent-focused or agent-neutral

A fundamental distinction can be drawn between theories which require that agents act for ends perhaps disconnected from their own interests and drives, and theories which permit that agents act for ends in which they have some personal interest or motivation. These are called "agent-neutral" and "agent-focused" theories respectively.

Agent-neutral consequentialism ignores the specific value a state of affairs has for any particular agent. Thus, in an agent-neutral theory, an actor's personal goals do not count any more than anyone else's goals in evaluating what action the actor should take. Agent-focused consequentialism, on the other hand, focuses on the particular needs of the moral agent. Thus, in an agent-focused account, such as one that Peter Railton outlines, the agent might be concerned with the general welfare, but the agent is more concerned with the immediate welfare of herself and her friends and family.

These two approaches could be reconciled by acknowledging the tension between an agent's interests as an individual and as a member of various groups, and seeking to somehow optimize among all of these interests. For example, it may be meaningful to speak of an action as being good for someone as an individual, but bad for them as a citizen of their town.

Human-centered?

Many consequentialist theories may seem primarily concerned with human beings and their relationships with other human beings. However, some philosophers argue that we should not limit our ethical consideration to the interests of human beings alone. Jeremy Bentham, who is regarded as the founder of utilitarianism, argues that animals can experience pleasure and pain, thus demanding that 'non-human animals' should be a serious object of moral concern.

More recently, Peter Singer has argued that it is unreasonable that we do not give equal consideration to the interests of animals as to those of human beings when we choose the way we are to treat them. Such equal consideration does not necessarily imply identical treatment of humans and non-humans, any more than it necessarily implies identical treatment of all humans.

Value of consequences

One way to divide various consequentialisms is by the types of consequences that are taken to matter most, that is, which consequences count as good states of affairs. According to utilitarianism, a good action is one that results in an increase in pleasure, and the best action is one that results in the most pleasure for the greatest number. Closely related is eudaimonic consequentialism, according to which a full, flourishing life, which may or may not be the same as enjoying a great deal of pleasure, is the ultimate aim. Similarly, one might adopt an aesthetic consequentialism, in which the ultimate aim is to produce beauty. However, one might fix on non-psychological goods as the relevant effect. Thus, one might pursue an increase in material equality or political liberty instead of something like the more ephemeral "pleasure". Other theories adopt a package of several goods, all to be promoted equally. As the consequentialist approach contains an inherent assumption that the outcomes of a moral decision can be quantified in terms of "goodness" or "badness," or at least put in order of increasing preference, it is an especially suited moral theory for a probabilistic and decision theoretical approach.

Virtue ethics

Consequentialism can also be contrasted with aretaic moral theories such as virtue ethics. Whereas consequentialist theories posit that consequences of action should be the primary focus of our thinking about ethics, virtue ethics insists that it is the character rather than the consequences of actions that should be the focal point. Some virtue ethicists hold that consequentialist theories totally disregard the development and importance of moral character. For example, Philippa Foot argues that consequences in themselves have no ethical content, unless it has been provided by a virtue such as benevolence.

However, consequentialism and virtue ethics need not be entirely antagonistic. Iain King has developed an approach that reconciles the two schools. Other consequentialists consider effects on the character of people involved in an action when assessing consequence. Similarly, a consequentialist theory may aim at the maximization of a particular virtue or set of virtues. Finally, following Foot's lead, one might adopt a sort of consequentialism that argues that virtuous activity ultimately produces the best consequences.

Ultimate end

The ultimate end is a concept in the moral philosophy of Max Weber, in which individuals act in a faithful, rather than rational, manner.

We must be clear about the fact that all ethically oriented conduct may be guided by one of two fundamentally differing and irreconcilably opposed maxims: conduct can be oriented to an ethic of ultimate ends or to an ethic of responsibility. [...] There is an abysmal contrast between conduct that follows the maxim of an ethic of ultimate ends — that is in religious terms, "the Christian does rightly and leaves the results with the Lord" — and conduct that follows the maxim of an ethic of responsibility, in which case one has to give an account of the foreseeable results of one's action.

— Max Weber, Politics as a Vocation, 1918

Teleological ethics

Teleological ethics (Greek: telos, 'end, purpose' + logos, 'science') is a broader class of views in moral philosophy which consequentialism falls under. In general, proponents of teleological ethics argue that the moral value of any act consists in its tendency to produce things of intrinsic value, meaning that an act is right if and only if it, or the rule under which it falls, produces, will probably produce, or is intended to produce, a greater balance of good over evil than any alternative act. This concept is exemplified by the famous aphorism, "the end justifies the means," variously attributed to Machiavelli or Ovid i.e. if a goal is morally important enough, any method of achieving it is acceptable.

Teleological theories differ among themselves on the nature of the particular end that actions ought to promote. The two major families of views in teleological ethics are virtue ethics and consequentialism. Teleological ethical theories are often discussed in opposition to deontological ethical theories, which hold that acts themselves are inherently good or bad, rather than good or bad because of extrinsic factors (such as the act's consequences or the moral character of the person who acts).

Etymology

The term consequentialism was coined by G. E. M. Anscombe in her essay "Modern Moral Philosophy" in 1958, to describe what she saw as the central error of certain moral theories, such as those propounded by Mill and Sidgwick.

The phrase and concept of "the end justifies the means" are at least as old as the first century BC. Ovid wrote in his Heroides that Exitus acta probat ("The result justifies the deed").

Criticisms

G. E. M. Anscombe objects to the consequentialism of Sidgwick on the grounds that the moral worth of an action is premised on the predictive capabilities of the individual, relieving them of the responsibility for the "badness" of an act should they "make out a case for not having foreseen" negative consequences.

The future amplification of the effects of small decisions is an important factor that makes it more difficult to predict the ethical value of consequences, even though most would agree that only predictable consequences are charged with a moral responsibility.

Bernard Williams has argued that consequentialism is alienating because it requires moral agents to put too much distance between themselves and their own projects and commitments. Williams argues that consequentialism requires moral agents to take a strictly impersonal view of all actions, since it is only the consequences, and not who produces them, that are said to matter. Williams argues that this demands too much of moral agents—since (he claims) consequentialism demands that they be willing to sacrifice any and all personal projects and commitments in any given circumstance in order to pursue the most beneficent course of action possible. He argues further that consequentialism fails to make sense of intuitions that it can matter whether or not someone is personally the author of a particular consequence. For example, that participating in a crime can matter, even if the crime would have been committed anyway, or would even have been worse, without the agent's participation.

Some consequentialists—most notably Peter Railton—have attempted to develop a form of consequentialism that acknowledges and avoids the objections raised by Williams. Railton argues that Williams's criticisms can be avoided by adopting a form of consequentialism in which moral decisions are to be determined by the sort of life that they express. On his account, the agent should choose the sort of life that will, on the whole, produce the best overall effects.