Social degeneration was a widely influential concept at the interface of the social and biological sciences in the 18th and 19th centuries. During the 18th century, scientific thinkers including Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, and Immanuel Kant argued that humans shared a common origin but had degenerated over time due to differences in climate. This theory provided an explanation of where humans came from and why some people appeared differently from others. In contrast, degenerationists in the 19th century feared that civilization might be in decline and that the causes of decline lay in biological change. These ideas derived from pre-scientific concepts of heredity ("hereditary taint") with Lamarckian emphasis on biological development through purpose and habit. Degeneration concepts were often associated with authoritarian political attitudes, including militarism and scientific racism, and a preoccupation with eugenics. The theory originated in racial concepts of ethnicity, recorded in the writings of such medical scientists as Johann Blumenbach and Robert Knox. From the 1850s, it became influential in psychiatry through the writings of Bénédict Morel, and in criminology with Cesare Lombroso. By the 1890s, in the work of Max Nordau and others, degeneration became a more general concept in social criticism. It also fed into the ideology of ethnic nationalism, attracting, among others, Maurice Barrès, Charles Maurras and the Action Française. Alexis Carrel, a French Nobel Laureate in Medicine, cited national degeneration as a rationale for a eugenics programme in collaborationist Vichy France.

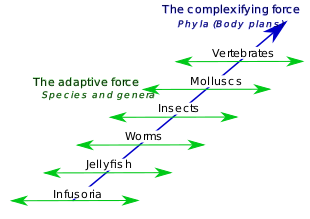

The meaning of degeneration was poorly defined, but can be described as an organism's change from a more complex to a simpler, less differentiated form, and is associated with 19th-century conceptions of biological devolution. In scientific usage, the term was reserved for changes occurring at a histological level – i.e. in body tissues. Although rejected by Charles Darwin, the theory's application to the social sciences was supported by some evolutionary biologists, most notably Ernst Haeckel and Ray Lankester. As the 19th century wore on, the increasing emphasis on degeneration reflected an anxious pessimism about the resilience of European civilization and its possible decline and collapse.

Theories of degeneration in the 18th century

In the second half of the eighteenth century, degeneration theory gained prominence as an explanation of the nature and origin of human difference. Among the most notable proponents of this theory was Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon. A gifted mathematician and eager naturalist, Buffon served as the curator of the Parisian Cabinet du Roi. The collections of the Cabinet du Roi served as the inspiration for Buffon's encyclopedic Histoire Naturelle, of which he published thirty-six volumes between 1749 and his death in 1788. In the Histoire Naturelle, Buffon asserted that differences in climate created variety within species. He believed that these changes occurred gradually and initially affected only a few individuals before becoming widespread. Buffon relied on an argument from analogy to contend that this process of degeneration occurred among humans. He claimed to have observed the transformation of certain animals by their climate and concluded that such changes must have also shaped humankind.

Buffon maintained that degeneration had particularly adverse consequences in the New World. He believed America to be both colder and wetter than Europe. This climate limited the number of species in the New World and prompted a decline in size and vigor among the animals which did survive. Buffon also applied these principles to the people of the New World. He wrote in the Histoire Naturelle that the indigenous people lacked the ability to feel strong emotion for others. For Buffon, these individuals were incapable of love as well as desire.

Buffon's theory of degeneration attracted the ire of many early American elites who feared that Buffon's depiction of the New World would negatively influence European perceptions of their nation. In particular, Thomas Jefferson mounted a vigorous defense of the American natural world. He attacked the premises of Buffon's argument in his 1785 Notes on the State of Virginia, writing that the animals of the New World felt the same sun and walked upon the same soil as their European counterparts. Jefferson believed that he could permanently alter Buffon's views of the New World by showing him firsthand the majesty of American wildlife. While serving as minister to France, Jefferson wrote repeatedly to his compatriots in the United States, pleading them to send a stuffed moose to Paris. After months of effort, General John Sullivan responded to Jefferson's request and shipped a moose to France. Buffon died only three months after the moose's arrival, and his theory of New World degeneration remained forever preserved in the pages of the Histoire Naturelle.

In the years following Buffon's death, the theory of degeneration gained a number of new followers, many of whom were concentrated in German-speaking lands. The anatomist and naturalist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach praised Buffon in his lectures at the University of Göttingen. He adopted Buffon's theory of degeneration in his dissertation De Generis Humani Varietate Nativa. The central premise of this work was that all of mankind belonged to the same species. Blumenbach believed that a multitude of factors, including climate, air, and the strength of the sun, promoted degeneration and resulted in external differences between human beings. However, he also asserted that these changes could easily be undone and, thus, did not constitute the basis for speciation. In the essay “Über Menschen-Rassen und Schweine-Rassen,” Blumenbach clarified his understanding of the relationship between different human races by calling upon the example of the pig. He contended that, if the domestic pig and the wild boar were seen as belonging to the same species, then different humans, regardless of skin color or height, must too belong to the same species. For Blumenbach, all people of the world existed as different gradations on a spectrum. Nevertheless, the third edition of De Generis Humani Varietate Nativa, published in 1795, is famed among scholars for its introduction of a system of racial classification which divided humans into members of the Caucasian, Ethiopian, Mongolian, Malayan, or American races.

Blumenbach's views on degeneration emerged in dialogue with the works of other thinkers concerned with race and origin in the late eighteenth century. In particular, Blumenbach participated in fruitful intellectual exchange with another prominent German scholar of his age, Immanuel Kant. Kant, a philosopher and professor at the University of Königsberg, taught a course on physical geography for some forty years, fostering an interest in biology and taxonomy. Like Blumenbach, Kant engaged closely with the writings of Buffon while developing his position on these subjects.

In his 1777 essay “Von der verschiedenen Racen der Menschen,” Kant expressed the belief that all humans shared a common origin. He called upon the ability of humans to interbreed as evidence for this assertion. Additionally, Kant introduced the term “degeneration,” which he defined as hereditary differences between groups with a shared root. Kant also arrived at a meaning of “race” from this definition of degeneration. He claimed that races developed when degenerations were preserved over a long period of time. A group could only constitute a race if breeding with a different degeneration resulted in “intermediate offspring." Although Kant advocated for a theory of shared human origin, he also contended that there was an innate hierarchy between existing races. In 1788, Kant wrote “Über den Gebrauch teleologischer Prinzipien.” He maintained in this work that a human's place in nature was determined by the amount of sweat the individual produced, which revealed an innate ability to survive. Sweat emerged from the skin. Therefore, skin color indicated important distinctions between humans.

History

The concept of degeneration arose during the European enlightenment and the industrial revolution – a period of profound social change and a rapidly shifting sense of personal identity. Several influences were involved.

The first related to the extreme demographic upheavals, including urbanization, in the early years of the 19th century. The disturbing experience of social change and urban crowds, largely unknown in the agrarian 18th century, was recorded in the journalism of William Cobbett, the novels of Charles Dickens and in the paintings of J M W Turner. These changes were also explored by early writers on social psychology, including Gustav Le Bon and Georg Simmel. The psychological impact of industrialisation is comprehensively described in Humphrey Jennings' masterly anthology Pandaemonium 1660 - 1886. Victorian social reformers including Edwin Chadwick, Henry Mayhew and Charles Booth voiced concerns about the "decline" of public health in the urban life of the British working class, arguing for improved housing and sanitation, access to parks and recreational facilities, an improved diet and a reduction in alcohol intake. These contributions from the public health perspective were discussed by the Scottish physician Sir James Cantlie in his influential 1885 lecture Degeneration Amongst Londoners. The novel experience of everyday contact with the urban working classes gave rise to a kind of horrified fascination with their perceived reproductive energies which appeared to threaten middle-class culture.

Secondly, the proto-evolutionary biology and transformatist speculations of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and other natural historians—taken together with the Baron von Cuvier's theory of extinctions—played an important part in establishing a sense of the unsettled aspects of the natural world. The polygenic theories of multiple human origins, supported by Robert Knox in his book The Races of Men, were firmly rejected by Charles Darwin who, following James Cowles Prichard, generally agreed on a single African origin for the entire human species.

Thirdly, the development of world trade and colonialism, the early European experience of globalization, resulted in an awareness of the varieties of cultural expression and the vulnerabilities of Western civilization.

Finally, the growth of historical scholarship in the 18th century, exemplified by Edward Gibbon's The History of the Decline and Fall of The Roman Empire (1776–1789), excited a renewed interest in the narratives of historical decline. This resonated uncomfortably with the difficulties of French political life in the post-revolutionary nineteenth century.

Degeneration theory achieved a detailed articulation in Bénédict Morel's Treatise on Degeneration of the Human Species (1857), a complicated work of clinical commentary from an asylum in Normandy (Saint Yon in Rouen) which, in the popular imagination at least, coalesced with de Gobineau's Essay on The Inequality of the Human Races (1855). Morel's concept of mental degeneration – in which he believed that intoxication and addiction in one generation of a family would lead to hysteria, epilepsy, sexual perversions, insanity, learning disability and sterility in subsequent generations – is an example of Lamarckian biological thinking, and Morel's medical discussions are reminiscent of the clinical literature surrounding syphilitic infection (syphilography). Morel's psychiatric theories were taken up and advocated by his friend Philippe Buchez, and through his political influence became an official doctrine in French legal and administrative medicine.

Arthur de Gobineau came from an impoverished family (with a domineering and adulterous mother) which claimed an aristocratic ancestry; he was a failed author of historical romances, and his wife was widely rumored to be a Créole from Martinique. De Gobineau nevertheless argued that the course of history and civilization was largely determined by ethnic factors, and that interracial marriage ("miscegenation") resulted in social chaos. De Gobineau built a successful career in the French diplomatic service, living for extended periods in Iran and Brazil, and spent his later years travelling through Europe, lamenting his mistreatment at the hands of his wife and daughters. He died of a heart attack in 1882 while boarding a train in Turin. His work was well received in German translation—not least by the composer Richard Wagner—and the leading German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin later wrote extensively on the dangers posed by degeneration to the German people. De Gobineau's writings exerted an enormous influence on the thinkers antecedent to the Third Reich – although they are curiously free of anti-Semitic prejudice. Quite different historical factors inspired the Italian Cesare Lombroso in his work on criminal anthropology with the notion of atavistic retrogression, probably shaped by his experiences as a young army doctor in Calabria during the risorgimento.

In Britain, degeneration received a scientific formulation from Ray Lankester whose detailed discussions of the biology of parasitism were hugely influential; the poor physical condition of many British Army recruits for the Second Boer War (1899–1902) led to alarm in government circles. Psychiatrist Henry Maudsley initially argued that degenerate family lines would die out with little social consequence, but later became more pessimistic about the effects of degeneration on the general population; Maudsley also warned against the use of the term "degeneration" in a vague and indiscriminate way. Anxieties in Britain about the perils of degeneration found legislative expression in the Mental Deficiency Act 1913 which gained strong support from Winston Churchill, then a senior member of the Liberal government.

In the fin-de-siècle period, Max Nordau scored an unexpected success with his bestselling Degeneration (1892). Sigmund Freud met Nordau in 1885 while he was studying in Paris and was notably unimpressed by him and hostile to the degeneration concept. Degeneration fell from popular and fashionable favor around the time of the First World War, although some of its preoccupations persisted in the writings of the eugenicists and social Darwinists (for example, R. Austin Freeman; Anthony Ludovici; Rolf Gardiner; and see also Dennis Wheatley's Letter to posterity). Oswald Spengler's The Decline of the West (1919) captured something of the degenerationist spirit in the aftermath of the war.

Psychology and Emil Kraepelin

Degeneration theory is, at its heart, a way of thinking, and something that is taught, not innate. A major influence on the theory was Emil Kraepelin, lining up degeneration theory with his psychiatry practice. The central idea of this concept was that in “degenerative” illness, there is a steady decline in mental functioning and social adaptation from one generation to the other. For example, there might be an intergenerational development from nervous character to major depressive disorder, to overt psychotic illness and, finally, to severe and chronic cognitive impairment, something akin to dementia. This theory was advanced decades before the rediscovery of Mendelian genetics and their application to medicine in general and to psychiatry in particular. Kraepelin and his colleagues mostly derived from degeneration theory broadly. He rarely made a specific references to the theory of degeneration, and his attitude towards degeneration theory was not straightforward. Positive, but more ambivalent. The concept of disease, especially chronic mental disease fit very well into this framework insofar these phenomena were regarded as signs of an evolution in the wrong direction, as a degenerative process which diverts from the usual path of nature.

However, he remained skeptical of over-simplistic versions of this concept: While commenting approvingly on the basic ideas of Cesare Lombroso's "criminal anthropology", he did not accept the popular idea of overt "stigmata of degeneration", by which individual persons could be identified as being "degenerated" simply by their physical appearance. While Kraepelin and his colleagues may not have focused on this, it did not stop others from advancing the converse idea.

An early application of this theory was the Mental Deficiency Act supported by Winston Churchill in 1913. This entailed placing those deemed “idiots” into separate colonies, and included those who showed sign of a “degeneration”. While this did apply to those with mental disorders of a psychiatric nature, the execution was not always in the same vein, as some of the language was used to the those “morally weak”, or deemed “idiots”. The belief in the existence of degeneration helped foster a sense that a sense of negative energy was inexplicable and was there to find sources of “rot” in society. This forwarded the notion the idea that society was structured in a way that produced regression, an outcome of the “darker side of progress”.

Those who had developed the label of "degenerate" as a means of qualifying difference in a negative manner could use the idea that this “darker side of progress” was inevitable by having the idea society could “rot". Considerations to the pervasiveness an allegedly superior condition were, during the nineteenth century, frighteningly reinforced the language and habits of destructive thinking.

The "dark side" of progress

The idea of progress was at once a social, political and scientific theory. The theory of evolution, as described in Darwin's The Origin of Species, provided for many social theorists the necessary scientific foundation for the idea of social and political progress. The terms evolution and progress were in fact often used interchangeably in the 19th century.

The rapid industrial, political and economic progress in 19th-century Europe and North America was, however, paralleled by a sustained discussion about increasing rates of crime, insanity, vagrancy, prostitution, and so forth. Confronted with this apparent paradox, evolutionary scientists, criminal anthropologists and psychiatrists postulated that civilization and scientific progress could be a cause of physical and social pathology as much as a defense against it. This led to the emergence of a general theory of degeneration, never reduced to a concrete, simple theory or axiom. Instead, the concept of degeneration was produced and refined within and between several discourses, including the human sciences, the natural sciences, fictional narratives and socio-political commentaries. A broad outline of the theory, however, can be formulated, and it runs as follows.

According to the theory of degeneration, a host of individual and social pathologies in a finite network of diseases, disorders and moral habits could be explained by a biologically based affliction. The primary symptoms of the affliction were thought to be a weakening of the vital forces and will power of its victim. In this way, a wide range of social and medical deviations, including crime, violence, alcoholism, prostitution, gambling, and pornography, could be explained by reference to a biological defect within the individual. The theory of degeneration was therefore predicated on evolutionary theory. The forces of degeneration opposed those of evolution, and those afflicted with degeneration were thought to represent a return to an earlier evolutionary stage. This can be seen socially when mixed race marriages started becoming more frequent as the 19th century progressed. Such mixed marriages, all but unthinkable in 1848 but now on the rise among Indo-European and even full-blood European women with native men, were attributed to the increasing impoverishment and declining welfare of these women on the one hand an "intellectual and social development" among certain classes of native the other. The issue, however, was rarely addressed since the gender hierarchy of the argument was contingent on assuming those who made such conjugal choices were neither well-bred nor deserved European standing. As more people began to mix with a race or people that was seen as lesser, degeneration theory became intertwined with development in a racial and colonial sense and more of these examples became common.

The poetics of degeneration was a poetics of social crisis. In the last decades of the century; Victorian social planners drew deeply on social Darwinism and the idea of degeneration to figure the social crises erupting relentlessly in the cities and colonies. Heightened debates converged with domestic and colonial social reform, cementing an offensive of a somewhat different order. It targeted the "dangerous" in paupered residuum and the growing population impoverished Indo-Europeans, the majority of whom were of mixed but legally classified as European. The world, being more globalized than ever before, continued to have more “crises” similar to these had by the leading classes, deterring the other as the enemy or downfall of society.

By the end of the 1870s, Britain was foundering in severe depression, and throughout the 1880s class tensions, the suffragette movement, a socialist revival, swelling poverty and the dearth of housing and jobs fed deepening middle class fears.

Selected quotes

"The word degenerate, when applied to a people, means that the people no longer has the same intrinsic value as it had before, because it has no longer the same blood in its veins, continual adulterations having gradually affected the quality of that blood....in fact, the man of a decadent time, the degenerate man properly so-called, is a different being from the racial point of view, from the heroes of the great ages....I think I am right in concluding that the human race in all its branches has a secret repulsion from the crossing of blood...." Arthur de Gobineau (1855) Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races.

"When under any kind of noxious influence an organism becomes debilitated, its successors will not resemble the healthy, normal type of the species, with capacities for development, but will form a new sub-species, which, like all others, possesses the capacity of transmitting to its offspring, in a continuously increasing degree, its peculiarities, these being morbid deviations from the normal form - gaps in development, malformations and infirmities..." Bénédict Morel (1857) Treatise on Degeneration.

"...Any new set of conditions which renders a species' food and safety very easily obtained, seems to lead to degeneration...." Ray Lankester (1880) Degeneration: A Chapter in Darwinism.

"We stand now in the midst of a severe mental epidemic; of a sort of black death of degeneration and hysteria, and it is natural that we should ask anxiously on all sides: 'What is to come next ?' " Max Nordau (1892) Degeneration.

"It has become the fashion to regard any symptom which is not obviously due to trauma or infection as a sign of degeneracy....this being so, it may well be asked whether an attribution of "degeneracy" is of any value, or adds anything to our knowledge..." Sigmund Freud (1905) Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality.

Development of the degeneration concept

The earliest uses of the term degeneration can be found in the writings of Blumenbach and Buffon at the end of the 18th century, when these early writers on natural history considered scientific approaches to the human species. With the taxonomic mind-set of natural historians, they drew attention to the different ethnic groupings of mankind, and raised general enquiries about their relationships, with the idea that racial groupings could be explained by environmental effects on a common ancestral stock. This pre-Darwinian belief in the heritability of acquired characteristics does not accord with modern genetics. An alternative view of the multiple origins of different racial groups, called "polygenic theories", was also rejected by Charles Darwin, who favored explanations in terms of differential geographic migrations from a single, probably African, population.

The theory of degeneration found its first detailed presentation in the writings of Bénédict Morel (1809–1873), especially in his Traité des dégénérescences physiques, intellectuelles et morales de l'espèce humaine (Treatise on Degeneration of the Human Species) (1857). This book was published two years before Darwin's Origin of Species. Morel was a highly regarded psychiatrist, the very successful superintendent of the Rouen asylum for almost twenty years and a fastidious recorder of the family histories of his variously disabled patients. Through the details of these family histories, Morel discerned an hereditary line of defective parents infected by pollutants and stimulants; a second generation liable to epilepsy, neurasthenia, sexual deviations and hysteria; a third generation prone to insanity; and a final generation doomed to congenital idiocy and sterility. In 1857, Morel proposed a theory of hereditary degeneracy, bringing together environmental and hereditary elements in an uncompromisingly pre-Darwinian mix. Morel's contribution was further developed by Valentin Magnan (1835–1916), who stressed the role of alcohol—particularly absinthe—in the generation of psychiatric disorders.

Morel's ideas were greatly extended by the Italian medical scientist Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909) whose work was defended and translated into English by Havelock Ellis. In his L'uomo delinquente (1876), Lombroso outlined a comprehensive natural history of the socially deviant person and detailed the stigmata of the person who was born to be criminally insane. These included a low, sloping forehead, hard and shifty eyes, large, handle-shaped ears, a flattened or upturned nose, a forward projection of the jaw, irregular teeth, prehensile toes and feet, long simian arms and a scanty beard and baldness. Lombroso also listed the features of the degenerate mentality, supposedly released by the disinhibition of the primitive neurological centres. These included apathy, the loss of moral sense, a tendency to impulsiveness or self-doubt, an unevenness of mental qualities such as unusual memory or aesthetic abilities, a tendency to mutism or to verbosity, excessive originality, preoccupation with the self, mystical interpretations placed on simple facts or perceptions, the abuse of symbolic meanings and the magical use of words, or mantras. Lombroso, with his concept of atavistic retrogression, suggested an evolutionary reversion, complementing hereditary degeneracy, and his work in the medical examination of criminals in Turin resulted in his theory of criminal anthropology—a constitutional notion of abnormal personality that was not actually supported by his own scientific investigations. In his later life, Lombroso developed an obsession with spiritualism, engaging with the spirit of his long dead mother.

In 1892, Max Nordau, an expatriate Hungarian living in Paris, published his extraordinary bestseller Degeneration, which greatly extended the concepts of Bénédict Morel and Cesare Lombroso (to whom he dedicated the book) to the entire civilization of western Europe, and transformed the medical connotations of degeneration into a generalized cultural criticism. Adopting some of Charcot's neurological vocabulary, Nordau identified a number of weaknesses in contemporary Western culture which he characterized in terms of ego-mania, i.e., narcissism and hysteria. He also emphasized the importance of fatigue, enervation and ennui. Nordau, horrified by the anti-Semitism surrounding the Dreyfus affair, devoted his later years to Zionist politics. Degeneration theory fell from favour around the time of the First World War because of an improved understanding of the mechanisms of genetics as well as the increasing vogue for psychoanalytic thinking. However, some of its preoccupations lived on in the world of eugenics and social Darwinism. It is notable that the Nazi attack on western liberal society was largely couched in terms of degenerate art with its associations of racial miscegenation and fantasies of racial purity—and included as its target almost all modernist cultural experiment.

The role of women in furthering development of the concept of degeneration was reviewed by Anne McClintock, a professor of English at the University of Wisconsin, who found that women who were ambiguously placed on the so-called "imperial divide" (nurses, nannies, governesses, prostitutes and servants) happened to serve as boundary markers and mediators. These women were tasked with the purification and maintenance of boundaries and what was seen as "inferior" places in society they held at the time.

Degenerationist devices

Towards the close of the 19th century, in the fin-de-siècle period, something of an obsession with decline, descent and degeneration invaded the European creative imagination, partly fuelled by widespread misconceptions of Darwinian evolutionary theory. Among the main examples are the symbolist literary work of Charles Baudelaire, the Rougon-Macquart novels of Émile Zola, Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde—published in the same year (1886) as Richard von Krafft-Ebing's Psychopathia Sexualis—and, subsequently, Oscar Wilde's only novel (containing his aesthetic manifesto) The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891). In Tess of the d'Urbervilles (1891), Thomas Hardy explores the destructive consequences of a family myth of noble ancestry. Norwegian dramatist Henrik Ibsen showed a sensitivity to degenerationist thinking in his theatrical presentations of Scandinavian domestic crises. Arthur Machen's The Great God Pan (1890/1894), with its emphasis on the horrors of psychosurgery, is frequently cited as an essay on degeneration. A scientific twist was added by H.G. Wells in The Time Machine (1895) in which Wells prophesied the splitting of the human race into variously degenerate forms, and again in his The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896) wherein forcibly mutated animal-human hybrids keep reverting to their earlier forms. Joseph Conrad alludes to degeneration theory in his treatment of political radicalism in the 1907 novel The Secret Agent.

In her influential study The Gothic Body, Kelly Hurley draws attention to the literary device of the abhuman as a representation of damaged personal identity, and to lesser-known authors in the field, including Richard Marsh (1857–1915), author of The Beetle (1897), and William Hope Hodgson (1877–1918), author of The Boats of the Glen Carrig, The House on the Borderland and The Night Land. In 1897, Bram Stoker published Dracula, an enormously influential Gothic novel featuring the parasitic vampire Count Dracula in an extended exercise of reversed imperialism. Unusually, Stoker makes explicit reference to the writings of Lombroso and Nordau in the course of the novel. Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories include a host of degenerationist tropes, perhaps best illustrated (drawing on the ideas of Serge Voronoff) in The Adventure of the Creeping Man.