The Genesis creation narrative is the creation myth of both Judaism and Christianity [[DJS -- Islam? --]]. The narrative is made up of two stories, roughly equivalent to the first two chapters of the Book of Genesis. In the first, Elohim (the Hebrew generic word for God) creates the heavens and the Earth in six days, then rests on, blesses and sanctifies the seventh (i.e. the Biblical Sabbath). In the second story, God, now referred to by the personal name Yahweh, creates Adam, the first man, from dust and places him in the Garden of Eden, where he is given dominion over the animals. Eve, the first woman, is created from Adam as his companion.

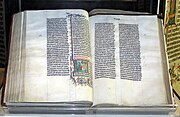

It expounds themes parallel to those in Mesopotamian mythology, emphasizing the Israelite people's belief in one God. The first major comprehensive draft of the Pentateuch (the series of five books which begins with Genesis and ends with Deuteronomy) was composed in the late 7th or the 6th century BCE (the Jahwist source) and was later expanded by other authors (the Priestly source) into a work very like Genesis as known today. The two sources can be identified in the creation narrative: Priestly and Jahwistic. The combined narrative is a critique of the Mesopotamian theology of creation: Genesis affirms monotheism and denies polytheism. Robert Alter described the combined narrative as "compelling in its archetypal character, its adaptation of myth to monotheistic ends".

In recent centuries, some believers have used this narrative as evidence of literal creationism, leading them to subsequently deny evolution. Scholars do not consider Genesis to be historically accurate.

Composition

Sources

Although tradition attributes Genesis to Moses, biblical scholars hold that it, together with the following four books (making up what Jews call the Torah and biblical scholars call the Pentateuch), is "a composite work, the product of many hands and periods." A common hypothesis among biblical scholars today is that the first major comprehensive draft of the Pentateuch was composed in the late 7th or the 6th century BCE (the Jahwist source), and that this was later expanded by the addition of various narratives and laws (the Priestly source) into a work very like the one existing today.

As for the historical background which led to the creation of the narrative itself, a theory which has gained considerable interest, although still controversial, is "Persian imperial authorisation". This proposes that the Persians, after their conquest of Babylon in 538 BCE, agreed to grant Jerusalem a large measure of local autonomy within the empire, but required the local authorities to produce a single law code accepted by the entire community. It further proposes that there were two powerful groups in the community – the priestly families who controlled the Temple, and the landowning families who made up the "elders" – and that these two groups were in conflict over many issues, and that each had its own "history of origins", but the Persian promise of greatly increased local autonomy for all provided a powerful incentive to cooperate in producing a single text.

Structure

The creation narrative is made up of two stories, roughly equivalent to the two first chapters of the Book of Genesis (there are no chapter divisions in the original Hebrew text; see Chapters and verses of the Bible). The first account (Genesis 1:1–2:3) employs a repetitious structure of divine fiat and fulfillment, then the statement "And there was evening and there was morning, the [xth] day," for each of the six days of creation. In each of the first three days there is an act of division: day one divides the darkness from light, day two the "waters above" from the "waters below", and day three the sea from the land. In each of the next three days these divisions are populated: day four populates the darkness and light with Sun, Moon and stars; day five populates seas and skies with fish and fowl; and finally land-based creatures and mankind populate the land.

Consistency was evidently not seen as essential to storytelling in ancient Near Eastern literature. The overlapping stories of Genesis 1 and 2 are contradictory but also complementary, with the first (the Priestly story) concerned with the creation of the entire cosmos while the second (the Yahwist story) focuses on man as moral agent and cultivator of his environment. The highly regimented seven-day narrative of Genesis 1 features an omnipotent God who creates a god-like humanity, while the one-day creation of Genesis 2 uses a simple linear narrative, a God who can fail as well as succeed, and a humanity which is not god-like but is punished for acts which would lead to their becoming god-like. Even the order and method of creation differs. "Together, this combination of parallel character and contrasting profile point to the different origin of materials in Genesis 1 and Genesis 2, however elegantly they have now been combined."

The primary accounts in each chapter are joined by a literary bridge at Genesis 2:4, "These are the generations of the heavens and of the earth when they were created." This echoes the first line of Genesis 1, "In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth", and is reversed in the next phrase, "...in the day that the LORD God made the earth and the heavens". This verse is one of ten "generations" (Hebrew: תולדות toledot) phrases used throughout Genesis, which provide a literary structure to the book. They normally function as headings to what comes after, but the position of this, the first of the series, has been the subject of much debate.

Mesopotamian influence

Comparative mythology provides historical and cross-cultural perspectives for Jewish mythology. Both sources behind the Genesis creation narrative borrowed themes from Mesopotamian mythology, but adapted them to their belief in one God, establishing a monotheistic creation in opposition to the polytheistic creation myth of ancient Israel's neighbors.

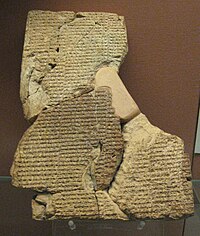

Genesis 1–11 as a whole is imbued with Mesopotamian myths. Genesis 1 bears both striking differences from and striking similarities to Babylon's national creation myth, the Enuma Elish. On the side of similarities, both begin from a stage of chaotic waters before anything is created, in both a fixed dome-shaped "firmament" divides these waters from the habitable Earth, and both conclude with the creation of a human called "man" and the building of a temple for the god (in Genesis 1, this temple is the entire cosmos). On the side of contrasts, Genesis 1 is monotheistic; it makes no attempt to account for the origins of God, and there is no trace of the resistance to the reduction of chaos to order (Greek: theomachy, lit. "God-fighting"), all of which mark the Mesopotamian creation accounts. Still, Genesis 1 bears similarities to the Baal Cycle of Israel's neighbor, Ugarit.

The Enuma Elish has also left traces on Genesis 2. Both begin with a series of statements of what did not exist at the moment when creation began; the Enuma Elish has a spring (in the sea) as the point where creation begins, paralleling the spring (on the land – Genesis 2 is notable for being a "dry" creation story) in Genesis 2:6 that "watered the whole face of the ground"; in both myths, Yahweh/the gods first create a man to serve him/them, then animals and vegetation. At the same time, and as with Genesis 1, the Jewish version has drastically changed its Babylonian model: Eve, for example, seems to fill the role of a mother goddess when, in Genesis 4:1, she says that she has "created a man with Yahweh", but she is not a divine being like her Babylonian counterpart.

Genesis 2 has close parallels with a second Mesopotamian myth, the Atra-Hasis epic – parallels that in fact extend throughout Genesis 2–11, from the Creation to the Flood and its aftermath. The two share numerous plot-details (e.g. the divine garden and the role of the first man in the garden, the creation of the man from a mixture of earth and divine substance, the chance of immortality, etc.), and have a similar overall theme: the gradual clarification of man's relationship with God(s) and animals.

Creation by word and creation by combat

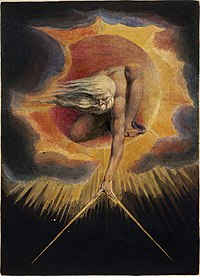

The narratives in Genesis 1 and 2 were not the only creation myths in ancient Israel, and the complete biblical evidence suggests two contrasting models. The first is the "logos" (meaning speech) model, where a supreme God "speaks" dormant matter into existence. The second is the "agon" (meaning struggle or combat) model, in which it is God's victory in battle over the monsters of the sea that mark his sovereignty and might. Genesis 1 is an example of creation by speech, while Psalm 74 and Isaiah 51 are examples of the "agon" mythology, recalling a Canaanite myth in which God creates the world by vanquishing the water deities: "Awake, awake! ... It was you that hacked Rahab in pieces, that pierced the Dragon! It was you that dried up the Sea, the waters of the great Deep, that made the abysses of the Sea a road that the redeemed might walk..."

First narrative: Genesis 1:1–2:3

Background

The cosmos created in Genesis 1 bears a striking resemblance to the Tabernacle in Exodus 35–40, which was the prototype of the Temple in Jerusalem and the focus of priestly worship of Yahweh; for this reason, and because other Middle Eastern creation stories also climax with the construction of a temple/house for the creator-god, Genesis 1 can be interpreted as a description of the construction of the cosmos as God's house, for which the Temple in Jerusalem served as the earthly representative.

The word bara is translated as "created" in English, but the concept it embodied was not the same as the modern term: in the world of the ancient Near East, the gods demonstrated their power over the world not by creating matter but by fixing destinies, so that the essence of the bara which God performs in Genesis concerns bringing "heaven and earth" (a set phrase meaning "everything") into existence by organising and assigning roles and functions.

The use of numbers in ancient texts was often numerological rather than factual – that is, the numbers were used because they held some symbolic value to the author. The number seven, denoting divine completion, permeates Genesis 1: verse 1:1 consists of seven words, verse 1:2 of fourteen, and 2:1–3 has 35 words (5×7); Elohim is mentioned 35 times, "heaven/firmament" and "earth" 21 times each, and the phrases "and it was so" and "God saw that it was good" occur 7 times each.

Among commentators, symbolic interpretation of the numbers may coexist with factual interpretations. Numerologically significant patterns of repeated words and phrases are termed "Hebraic meter". They begin in the creation narrative and continue through the book of Genesis.

Pre-creation: Genesis 1:1–2

- 1 In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.

- 2 And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness [was] upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

Although the opening phrase of Genesis 1:1 is commonly translated in English as above, the Hebrew is ambiguous, and can be translated at least three ways:

- as a statement that the cosmos had an absolute beginning ("In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.");

- as a statement describing the condition of the world when God began creating ("When in the beginning God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was untamed and shapeless."); and

- essentially similar to the second version but taking all of Genesis 1:2 as background information ("When in the beginning God created the heavens and the earth – the earth being untamed and shapeless... – God said, Let there be light!").

The second seems to be the meaning intended by the original Priestly author: the verb bara is used only of God (people do not engage in bara), and it concerns the assignment of roles, as in the creation of the first people as "male and female" (i.e., it allocates them sexes): in other words, the power of God is being shown not by the creation of matter but by the fixing of destinies.

The heavens and the earth is a set phrase meaning "everything", i.e., the cosmos. This was made up of three levels, the habitable earth in the middle, the heavens above, and an underworld below, all surrounded by a watery "ocean" of chaos as the Babylonian Tiamat. The Earth itself was a flat disc, surrounded by mountains or sea. Above it was the firmament, a transparent but solid dome resting on the mountains, allowing men to see the blue of the waters above, with "windows" to allow the rain to enter, and containing the Sun, Moon and stars. The waters extended below the Earth, which rested on pillars sunk in the waters, and in the underworld was Sheol, the abode of the dead.

The opening of Genesis 1 continues: "And the earth was formless and void..." The phrase "formless and void" is a translation of the Hebrew tohu wa-bohu, (Hebrew: תֹהוּ וָבֹהוּ), chaos, the condition that bara, ordering, remedies. Tohu by itself means "emptiness, futility"; it is used to describe the desert wilderness; bohu has no known meaning and was apparently coined to rhyme with and reinforce tohu. The phrase appears also in Jeremiah 4:23 where the prophet warns Israel that rebellion against God will lead to the return of darkness and chaos, "as if the earth had been 'uncreated'".

The opening of Genesis 1 concludes with a statement that "darkness was on the face of the deep" (Hebrew: תְהוֹם tehôm), [the] "darkness" and the "deep" being two of the three elements of the chaos represented in tohu wa-bohu (the third is the "formless earth"). In the Enuma Elish, the "deep" is personified as the goddess Tiamat, the enemy of Marduk; here it is the formless body of primeval water surrounding the habitable world, later to be released during the Deluge, when "all the fountains of the great deep burst forth" from the waters beneath the earth and from the "windows" of the sky.

The ruach of God moves over the face of the deep before creation begins. Ruach (רוּחַ) has the meanings "wind, spirit, breath", and elohim can mean "great" as well as "god": the ruach elohim may therefore mean the "wind/breath of God" (the storm-wind is God's breath in Psalms 18:16 and elsewhere, and the wind of God returns in the Flood story as the means by which God restores the Earth), or God's "spirit", a concept which is somewhat vague in the Hebrew Bible, or it may simply signify a great storm-wind.

Six days of Creation: Genesis 1:3–2:3

God's first act was the creation of undifferentiated light; dark and light were then separated into night and day, their order (evening before morning) signifying that this was the liturgical day; and then the Sun, Moon and stars were created to mark the proper times for the festivals of the week and year. Only when this is done does God create man and woman and the means to sustain them (plants and animals). At the end of the sixth day, when creation is complete, the world is a cosmic temple in which the role of humanity is the worship of God. This parallels Mesopotamian myth (the Enuma Elish) and also echoes chapter 38 of the Book of Job, where God recalls how the stars, the "sons of God", sang when the corner-stone of creation was laid.

First day

3 And God said: 'Let there be light.' And there was light. 4 And God saw the light, that it was good; and God divided the light from the darkness. 5 And God called the light Day, and the darkness He called Night. And there was evening and there was morning, one day.

Day 1 begins with the creation of light. God creates by spoken command and names the elements of the world as he creates them. In the ancient Near East the act of naming was bound up with the act of creating: thus in Egyptian literature the creator god pronounced the names of everything, and the Enûma Elish begins at the point where nothing has yet been named. God's creation by speech also suggests that he is being compared to a king, who has merely to speak for things to happen.

Second day

6 And God said: 'Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters.' 7 And God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament; and it was so. 8 And God called the firmament Heaven. And there was evening and there was morning, a second day.

Rāqîa, the word translated as firmament, is from rāqa', the verb used for the act of beating metal into thin plates. Created on the second day of creation and populated by luminaries on the fourth, it is a solid dome which separates the Earth below from the heavens and their waters above, as in Egyptian and Mesopotamian belief of the same time. In Genesis 1:17 the stars are set in the raqia'; in Babylonian myth the heavens were made of various precious stones (compare Exodus 24:10 where the elders of Israel see God on the sapphire floor of heaven), with the stars engraved in their surface.

Third day

And God said: 'Let the waters under the heaven be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear.' And it was so. 10 And God called the dry land Earth, and the gathering together of the waters called He Seas; and God saw that it was good. 11 And God said: 'Let the earth put forth grass, herb yielding seed, and fruit-tree bearing fruit after its kind, wherein is the seed thereof, upon the earth.' And it was so. 12 And the earth brought forth grass, herb yielding seed after its kind, and tree bearing fruit, wherein is the seed thereof, after its kind; and God saw that it was good. 13 And there was evening and there was morning, a third day.

On the third day, the waters withdraw, creating a ring of ocean surrounding a single circular continent. By the end of the third day God has created a foundational environment of light, heavens, seas and earth. The three levels of the cosmos are next populated in the same order in which they were created – heavens, sea, earth.

God does not create or make trees and plants, but instead commands the earth to produce them. The underlying theological meaning seems to be that God has given the previously barren earth the ability to produce vegetation, and it now does so at his command. "According to (one's) kind" appears to look forward to the laws found later in the Pentateuch, which lay great stress on holiness through separation.

Fourth day

14 And God said: 'Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs, and for seasons, and for days and years; 15 and let them be for lights in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth.' And it was so. 16 And God made the two great lights: the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night; and the stars. 17 And God set them in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth, 18 and to rule over the day and over the night, and to divide the light from the darkness; and God saw that it was good. 19 And there was evening and there was morning, a fourth day.

On Day Four the language of "ruling" is introduced: the heavenly bodies will "govern" day and night and mark seasons and years and days (a matter of crucial importance to the Priestly authors, as the three pilgrimage festivals were organised around the cycles of both the Sun and Moon, in a lunisolar calendar that could have either 12 or 13 months.); later, man will be created to rule over the whole of creation as God's regent. God puts "lights" in the firmament to "rule over" the day and the night. Specifically, God creates the "greater light," the "lesser light," and the stars. According to Victor Hamilton, most scholars agree that the choice of "greater light" and "lesser light", rather than the more explicit "Sun" and "Moon", is anti-mythological rhetoric intended to contradict widespread contemporary beliefs that the Sun and the Moon were deities themselves.

Fifth day

And God said: 'Let the waters swarm with swarms of living creatures, and let fowl fly above the earth in the open firmament of heaven.' 21 And God created the great sea-monsters, and every living creature that creepeth, wherewith the waters swarmed, after its kind, and every winged fowl after its kind; and God saw that it was good. 22 And God blessed them, saying: 'Be fruitful, and multiply, and fill the waters in the seas, and let fowl multiply in the earth.' 23 And there was evening and there was morning, a fifth day.

In the Egyptian and Mesopotamian mythologies, the creator-god has to do battle with the sea-monsters before he can make heaven and earth; in Genesis 1:21, the word tannin, sometimes translated as "sea monsters" or "great creatures", parallels the named chaos-monsters Rahab and Leviathan from Psalm 74:13, and Isaiah 27:1, and Isaiah 51:9, but there is no hint (in Genesis) of combat, and the tannin are simply creatures created by God.

Sixth day

24 And God said: 'Let the earth bring forth the living creature after its kind, cattle, and creeping thing, and beast of the earth after its kind.' And it was so. 25 And God made the beast of the earth after its kind, and the cattle after their kind, and every thing that creepeth upon the ground after its kind; and God saw that it was good.

26 And God said: 'Let us make man in our image, after our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.' 27 And God created man in His own image, in the image of God created He him; male and female created He them. 28 And God blessed them; and God said unto them: 'Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that creepeth upon the earth.' 29 And God said: 'Behold, I have given you every herb yielding seed, which is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree, in which is the fruit of a tree yielding seed--to you it shall be for food; 30 and to every beast of the earth, and to every fowl of the air, and to every thing that creepeth upon the earth, wherein there is a living soul, [I have given] every green herb for food.' And it was so.31 And God saw every thing that He had made, and, behold, it was very good. And there was evening and there was morning, the sixth day.

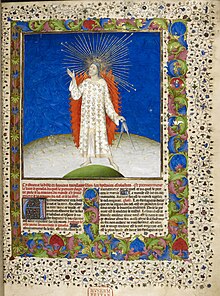

When in Genesis 1:26 God says "Let us make man", the Hebrew word used is adam; in this form it is a generic noun, "mankind", and does not imply that this creation is male. After this first mention the word always appears as ha-adam, "the man", but as Genesis 1:27 shows ("So God created man in his [own] image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them."), the word is still not exclusively male.

Man was created in the "image of God". The meaning of this is unclear: suggestions include:

- Having the spiritual qualities of God such as intellect, will, etc.;

- Having the physical form of God;

- A combination of these two;

- Being God's counterpart on Earth and able to enter into a relationship with him;

- Being God's representative or viceroy on Earth.

The fact that God says "Let us make man..." has given rise to several theories, of which the two most important are that "us" is majestic plural, or that it reflects a setting in a divine council with God enthroned as king and proposing the creation of mankind to the lesser divine beings.

God tells the animals and humans that he has given them "the green plants for food" – creation is to be vegetarian. Only later, after the Flood, is man given permission to eat flesh. The Priestly author of Genesis appears to look back to an ideal past in which mankind lived at peace both with itself and with the animal kingdom, and which could be re-achieved through a proper sacrificial life in harmony with God.

Upon completion, God sees that "every thing that He had made ... was very good" (Genesis 1:31). This implies that the materials that existed before the Creation ("tohu wa-bohu," "darkness," "tehom") were not "very good." Israel Knohl hypothesized that the Priestly source set up this dichotomy to mitigate the problem of evil.

Seventh day: divine rest

And the heaven and the earth were finished, and all the host of them. 2 And on the seventh day God finished His work which He had made; and He rested on the seventh day from all His work which He had made. 3 And God blessed the seventh day, and hallowed it; because that in it He rested from all His work which God in creating had made.

Creation is followed by rest. In ancient Near Eastern literature the divine rest is achieved in a temple as a result of having brought order to chaos. Rest is both disengagement, as the work of creation is finished, but also engagement, as the deity is now present in his temple to maintain a secure and ordered cosmos. Compare with Exodus 20:8–20:11: "Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy. Six days shalt thou labour, and do all thy work; but the seventh day is a sabbath unto the LORD thy GOD, in it thou shalt not do any manner of work, thou, nor thy son, nor thy daughter, nor thy man-servant, nor thy maid-servant, nor thy cattle, nor thy stranger that is within thy gates; for in six days the LORD made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that in them is, and rested on the seventh day; wherefore the LORD blessed the sabbath day, and hallowed it."

Second narrative: Genesis 2:4–2:25

Genesis 2–3, the Garden of Eden story, was probably authored around 500 BCE as "a discourse on ideals in life, the danger in human glory, and the fundamentally ambiguous nature of humanity – especially human mental faculties". The Garden in which the action takes place lies on the mythological border between the human and the divine worlds, probably on the far side of the cosmic ocean near the rim of the world; following a conventional ancient Near Eastern concept, the Eden river first forms that ocean and then divides into four rivers which run from the four corners of the earth towards its centre. It opens "in the day that the LORD God made the earth and the heavens", a set introduction similar to those found in Babylonian myths. Before the man is created the earth is a barren waste watered by an ’êḏ (אד); Genesis 2:6 the King James Version translated this as "mist", following Jewish practice, but since the mid-20th century Hebraists have generally accepted that the real meaning is "spring of underground water".

In Genesis 1 the characteristic word for God's activity is bara, "created"; in Genesis 2 the word used when he creates the man is yatsar (ייצר yîṣer), meaning "fashioned", a word used in contexts such as a potter fashioning a pot from clay. God breathes his own breath into the clay and it becomes nephesh (נֶ֫פֶשׁ), a word meaning "life", "vitality", "the living personality"; man shares nephesh with all creatures, but the text describes this life-giving act by God only in relation to man.

Eden, where God puts his Garden of Eden, comes from a root meaning "fertility": the first man is to work in God's miraculously fertile garden. The "tree of life" is a motif from Mesopotamian myth: in the Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 1800 BCE) the hero is given a plant whose name is "man becomes young in old age", but a serpent steals the plant from him. There has been much scholarly discussion about the type of knowledge given by the second tree. Suggestions include: human qualities, sexual consciousness, ethical knowledge, or universal knowledge; with the last being the most widely accepted. In Eden, mankind has a choice between wisdom and life, and chooses the first, although God intended them for the second.

The mythic Eden and its rivers may represent the real Jerusalem, the Temple and the Promised Land. Eden may represent the divine garden on Zion, the mountain of God, which was also Jerusalem; while the real Gihon was a spring outside the city (mirroring the spring which waters Eden); and the imagery of the Garden, with its serpent and cherubs, has been seen as a reflection of the real images of the Solomonic Temple with its copper serpent (the nehushtan) and guardian cherubs. Genesis 2 is the only place in the Bible where Eden appears as a geographic location: elsewhere (notably in the Book of Ezekiel) it is a mythological place located on the holy Mountain of God, with echoes of a Mesopotamian myth of the king as a primordial man placed in a divine garden to guard the tree of life.

"Good and evil" is a merism, in this case meaning simply "everything", but it may also have a moral connotation. When God forbids the man to eat from the tree of knowledge he says that if he does so he is "doomed to die": the Hebrew behind this is in the form used in the Bible for issuing death sentences.

The first woman is created out of one of Adam's ribs to be ezer kenegdo (עזר כנגדו ‘êzer kəneḡdō) – a term notably difficult to translate – to the man. Kəneḡdō means "alongside, opposite, a counterpart to him", and ‘êzer means active intervention on behalf of the other person. God's naming of the elements of the cosmos in Genesis 1 illustrated his authority over creation; now the man's naming of the animals (and of Woman) illustrates Adam's authority within creation.

The woman is called ishah (אשה ’iš-šāh), "Woman", with an explanation that this is because she was taken from ish (אִישׁ ’îš), meaning "man"; the two words are not in fact connected. Later, after the story of the Garden is complete, she receives a name: Ḥawwāh (חוה , Eve). This means "living" in Hebrew, from a root that can also mean "snake". Assyriologist Samuel Noah Kramer connects Eve's creation to the ancient Sumerian myth of Enki, who was healed by the goddess Nin-ti, "the Lady of the rib"; this became "the Lady who makes live" via a pun on the word ti, which means both "rib" and "to make live" in Sumerian. The Hebrew word traditionally translated "rib" in English can also mean "side", "chamber", or "beam". A long-standing exegetical tradition holds that the use of a rib from man's side emphasizes that both man and woman have equal dignity, for woman was created from the same material as man, shaped and given life by the same processes.

Creationism and the genre of the creation narrative

| Creationism |

|---|

|

The meaning to be derived from the Genesis creation narrative will depend on the reader's understanding of its genre, the literary "type" to which it belongs (e.g., scientific cosmology, creation myth, or historical saga). According to Biblical scholar Francis Andersen, misunderstanding the genre of the text—meaning the intention of the author(s) and the culture within which they wrote—will result in a misreading. Reformed evangelical scholar Bruce Waltke cautions against one such misreading: the "woodenly literal" approach, which leads to "creation science", but also to such "implausible interpretations" as the "gap theory", the presumption of a "young earth", and the denial of evolution. As scholar of Jewish studies, Jon D. Levenson, puts it:

How much history lies behind the story of Genesis? Because the action of the primeval story is not represented as taking place on the plane of ordinary human history and has so many affinities with ancient mythology, it is very far-fetched to speak of its narratives as historical at all."

Another scholar, Conrad Hyers, summed up the same thought by writing, "A literalist interpretation of the Genesis accounts is inappropriate, misleading, and unworkable [because] it presupposes and insists upon a kind of literature and intention that is not there."

Whatever else it may be, Genesis 1 is "story", since it features character and characterization, a narrator, and dramatic tension expressed through a series of incidents arranged in time. The Priestly author of Genesis 1 had to confront two major difficulties. First, there is the fact that since only God exists at this point, no-one was available to be the narrator; the storyteller solved this by introducing an unobtrusive "third person narrator". Second, there was the problem of conflict: conflict is necessary to arouse the reader's interest in the story, yet with nothing else existing, neither a chaos-monster nor another god, there cannot be any conflict. This was solved by creating a very minimal tension: God is opposed by nothingness itself, the blank of the world "without form and void." Telling the story in this way was a deliberate choice: there are a number of creation stories in the Bible, but they tend to be told in the first person, by Wisdom, the instrument by which God created the world; the choice of an omniscient third-person narrator in the Genesis narrative allows the storyteller to create the impression that everything is being told and nothing held back.

One can also regard Genesis as "historylike", "part of a broader spectrum of originally anonymous, history-like ancient Near Eastern narratives." Scholarly writings frequently refer to Genesis as myth, but there is no agreement on how to define "myth", and so while Brevard Childs famously suggested that the author of Genesis 1–11 "demythologised" his narrative, meaning that he removed from his sources (the Babylonian myths) those elements which did not fit with his own faith, others can say it is entirely mythical.

Genesis 1–2 reflects ancient ideas about science: in the words of E.A. Speiser, "on the subject of creation biblical tradition aligned itself with the traditional tenets of Babylonian science." The opening words of Genesis 1, "In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth", sum up the author(s) belief that Yahweh, the god of Israel, was solely responsible for creation and had no rivals. Later Jewish thinkers, adopting ideas from Greek philosophy, concluded that God's Wisdom, Word and Spirit penetrated all things and gave them unity. Christianity in turn adopted these ideas and identified Jesus with the creative word: "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God" (John 1:1). When the Jews came into contact with Greek thought, there followed a major reinterpretation of the underlying cosmology of the Genesis narrative. The biblical authors conceived the cosmos as a flat disc-shaped Earth in the centre, an underworld for the dead below, and heaven above. Below the Earth were the "waters of chaos", the cosmic sea, home to mythic monsters defeated and slain by God; in Exodus 20:4, God warns against making an image "of anything that is in the waters under the earth". There were also waters above the Earth, and so the raqia (firmament), a solid bowl, was necessary to keep them from flooding the world. During the Hellenistic period this was largely replaced by a more "scientific" model as imagined by Greek philosophers, according to which the Earth was a sphere at the centre of concentric shells of celestial spheres containing the Sun, Moon, stars and planets.

The idea that God created the world out of nothing (creatio ex nihilo) has become central today to Islam, Christianity, and Judaism – indeed, the medieval Jewish philosopher Maimonides felt it was the only concept that the three religions shared – yet it is not found directly in Genesis, nor in the entire Hebrew Bible. The Priestly authors of Genesis 1 were concerned not with the origins of matter (the material which God formed into the habitable cosmos), but with assigning roles so that the Cosmos should function. This was still the situation in the early 2nd century AD, although early Christian scholars were beginning to see a tension between the idea of world-formation and the omnipotence of God; by the beginning of the 3rd century this tension was resolved, world-formation was overcome, and creation ex nihilo had become a fundamental tenet of Christian theology.