In many cultures, witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers, usually to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term witchcraft originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have attacked their own community. Witchcraft was seen as immoral and often thought to involve communion with evil beings. It was believed witchcraft could be thwarted by protective magic or counter-magic, which could be provided by the cunning folk or folk healers. Suspected witches were also intimidated, banished, attacked or killed. Often they would be formally prosecuted and punished if found guilty. European witch-hunts and witch trials in the early modern period led to tens of thousands of executions - almost always of women who did not practice witchcraft. Although some folk healers were accused of witchcraft, they made up a minority of those accused. European belief in witchcraft gradually dwindled during and after the Age of Enlightenment.

Contemporary cultures that believe in magic and the supernatural often believe in witchcraft.Anthropologists have applied the term witchcraft to similar beliefs and occult practices described by many non-European cultures, and cultures that have adopted English will often call these practices "witchcraft", as well. As with the cunning-folk in Europe, Indigenous communities that believe in the existence of witchcraft define witches as the opposite of the healers and medicine people, who are sought out for protection against witches and witchcraft. Modern witch-hunting is found in parts of Africa and Asia.

A theory that witchcraft was a survival of a European pagan religion gained popularity in the early 20th century, but has since been discredited. In contemporary Western culture, most notably since the growth of Wicca from the 1950s, the term witchcraft has been redefined by some Modern Pagans and New Agers to refer to their self-help, healing and divination rituals.

Concept

The concept of witchcraft and the belief in its existence have persisted throughout recorded history. It has been found at various times and in many forms among cultures worldwide, and continues to have an important role in some cultures today. Most societies have believed in, and feared, an ability by some individuals to cause supernatural harm and misfortune to others. This may come from mankind's tendency "to want to assign occurrences of remarkable good or bad luck to agency, either human or superhuman". Witchcraft is seen by historians and anthropologists as one ideology for explaining misfortune, which has manifested in diverse ways. Some cultures have feared witchcraft much less than others, because they instead believed that strange misfortune was usually caused by gods, spirits, demons or fairies, or by other humans who have unwittingly cast the 'evil eye'.

Ronald Hutton outlined five key characteristics ascribed to witches and witchcraft by most cultures that believe in the concept. Traditionally, witchcraft was believed to be the use of magic to cause harm or misfortune to others; it was used by the witch against their own community; it was seen as immoral and often thought to involve communion with evil beings; powers of witchcraft were believed to have been acquired through inheritance or initiation; and witchcraft could be thwarted by defensive magic, persuasion, intimidation or physical punishment of the alleged witch.

Historically, the predominant concept of witchcraft in the Western world derives from Old Testament laws against witchcraft, and entered the mainstream when belief in witchcraft gained Church approval in the Early Modern Period. It is a theosophical conflict between good and evil, where witchcraft was generally evil and often associated with the Devil and Devil worship. This culminated in deaths, torture and scapegoating (casting blame for misfortune), and many years of large scale witch-trials and witch hunts, especially in Protestant Europe, before largely ceasing during the European Age of Enlightenment. Christian views in the modern day are diverse and cover the gamut of views from intense belief and opposition (especially by Christian fundamentalists) to non-belief, and even approval in some churches. From the mid-20th century, witchcraft – sometimes called contemporary witchcraft to clearly distinguish it from older beliefs – became the name of a branch of modern Paganism. It is most notably practiced in the Wiccan and modern witchcraft traditions, and it is no longer practiced in secrecy.

The Western mainstream Christian view is far from the only societal perspective about witchcraft. Many cultures worldwide continue to have widespread practices and cultural beliefs that are loosely translated into English as "witchcraft", although the English translation masks a very great diversity in their forms, magical beliefs, practices, and place in their societies. During the Age of Colonialism, many cultures across the globe were exposed to the modern Western world via colonialism, usually accompanied and often preceded by intensive Christian missionary activity (see "Christianization"). In these cultures beliefs that were related to witchcraft and magic were influenced by the prevailing Western concepts of the time. Witch-hunts, scapegoating, and the killing or shunning of suspected witches still occur in the modern era.

Suspicion of modern medicine due to beliefs about illness being due to witchcraft also continues in many countries to this day, with serious healthcare consequences. HIV/AIDS and Ebola virus disease are two examples of often-lethal infectious disease epidemics whose medical care and containment has been severely hampered by regional beliefs in witchcraft. Other severe medical conditions whose treatment is hampered in this way include tuberculosis, leprosy, epilepsy and the common severe bacterial Buruli ulcer.

Etymology and definitions

The word is over a thousand years old: Old English formed the compound wiccecræft from wicce ('witch') and cræft ('craft'). Witch was also spelled wicca or wycca in Old English, and was originally masculine. Folk etymologies link witchcraft "to the English words wit, wise, wisdom [Germanic root *weit-, *wait-, *wit-; Indo-European root *weid-, *woid-, *wid-]", so 'craft of the wise.'

In anthropological terminology, witches differ from sorcerers in that they don't use physical tools or actions to curse; their maleficium is perceived as extending from some intangible inner quality, and one may be unaware of being a witch, or may have been convinced of their nature by the suggestion of others. This definition was pioneered in a study of central African magical beliefs by E. E. Evans-Pritchard, who cautioned that it might not correspond with normal English usage.

Historians of European witchcraft have found the anthropological definition difficult to apply to European witchcraft, where witches could equally use (or be accused of using) physical techniques, as well as some who really had attempted to cause harm by thought alone.

Practices

Where belief in malicious magic practices exists, practitioners are typically forbidden by law as well as hated and feared by the general populace, while beneficial magic is tolerated or even accepted wholesale by the people — even if the orthodox establishment opposes it.

Spell casting

Probably the best-known characteristic of a witch is her ability to cast a spell – a set of words, a formula or verse, a ritual, or a combination of these, employed to do magic. Spells traditionally were cast by many methods, such as by the inscription of runes or sigils on an object to give that object magical powers; by the immolation or binding of a wax or clay image (poppet) of a person to affect them magically; by the recitation of incantations; by the performance of physical rituals; by the employment of magical herbs as amulets or potions; by gazing at mirrors, swords or other specula (scrying) for purposes of divination; and by many other means.

Necromancy (conjuring the dead)

Strictly speaking, necromancy is the practice of conjuring the spirits of the dead for divination or prophecy, although the term has also been applied to raising the dead for other purposes. The biblical Witch of Endor performed it (1 Sam. 28), and it is among the witchcraft practices condemned by Ælfric of Eynsham: "Witches still go to cross-roads and to heathen burials with their delusive magic and call to the devil; and he comes to them in the likeness of the man that is buried there, as if he arise from death."

White witches in Britain and Europe

Traditionally, the terms "witch" and "witchcraft" had negative connotations. Most societies that have believed in harmful witchcraft or 'black' magic have also believed in helpful or 'white' magic. In these societies, practitioners of helpful magic provided services such as breaking the effects of witchcraft, healing, divination, finding lost or stolen goods, and love magic. In Britain they were commonly known as cunning folk or wise people. Alan McFarlane writes, "There were a number of interchangeable terms for these practitioners, 'white', 'good', or 'unbinding' witches, blessers, wizards, sorcerers, however 'cunning-man' and 'wise-man' were the most frequent". Ronald Hutton prefers the term "service magicians". Often these people were involved in identifying alleged witches.

Hostile churchmen sometimes branded any magic-workers "witches" as a way of smearing them. Englishman Reginald Scot, who sought to disprove witchcraft and magic, wrote in The Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584), "At this day it is indifferent to say in the English tongue, 'she is a witch' or 'she is a wise woman'". Folk magicians throughout Europe were often viewed ambivalently by communities, and were considered as capable of harming as of healing, which could lead to their being accused as "witches" in the negative sense. Many English "witches" convicted of consorting with demons may have been cunning folk whose fairy familiars had been demonised; many French devins-guerisseurs ("diviner-healers") were accused of witchcraft, and over half the accused witches in Hungary seem to have been healers. Hutton (2017), however, says that "Service magicians were sometimes denounced as witches, but seem to have made up a minority of the accused in any area studied". Some of those who described themselves as contacting fairies described out-of-body experiences and travelling through the realms of an "other-world".

Thwarting witchcraft

Societies that believed in witchcraft also believed that it could be thwarted in various ways. One common way was to use protective magic or counter-magic, of which the cunning folk were experts. This included charms, talismans and amulets, anti-witch marks, witch bottles, witch balls, and burying objects such as horse skulls inside the walls of buildings. Another believed cure for bewitchment was to persuade or force the alleged witch to lift their spell. Often, people would attempt to thwart the witchcraft by physically punishing the alleged witch, such as by banishing, wounding, torturing or killing them. "In most societies, however, a formal and legal remedy was preferred to this sort of private action", whereby the alleged witch would be prosecuted and then formally punished if found guilty. This often resulted in execution.

Accusations of witchcraft

Éva Pócs writes that reasons for accusations of witchcraft fall into four general categories:

- A person was caught in the act of positive or negative sorcery

- A well-meaning sorcerer or healer lost their clients' or the authorities' trust

- A person did nothing more than gain the enmity of their neighbors

- A person was reputed to be a witch and surrounded with an aura of witch-beliefs or Occultism

She identifies three kinds of witch in popular belief:

- The "neighborhood witch" or "social witch": a witch who curses a neighbor following some dispute.

- The "magical" or "sorcerer" witch: either a professional healer, sorcerer, seer or midwife, or a person who has through magic increased her fortune to the perceived detriment of a neighboring household; due to neighborhood or community rivalries, and the ambiguity between positive and negative magic, such individuals can become branded as witches.

- The "supernatural" or "night" witch: portrayed in court narratives as a demon appearing in visions and dreams.

"Neighborhood witches" are the product of neighborhood tensions, and are found only in village communities where the inhabitants largely rely on each other. Such accusations follow the breaking of some social norm, such as the failure to return a borrowed item, and any person part of the normal social exchange could potentially fall under suspicion. Claims of "sorcerer" witches and "supernatural" witches could arise out of social tensions, but not exclusively; the supernatural witch often had nothing to do with communal conflict, but expressed tensions between the human and supernatural worlds; and in Eastern and Southeastern Europe such supernatural witches became an ideology explaining calamities that befell whole communities.

The historian Norman Gevitz has written:

[T]he medical arts played a significant and sometimes pivotal role in the witchcraft controversies of seventeenth-century New England. Not only were physicians and surgeons the principal professional arbiters for determining natural versus preternatural signs and symptoms of disease, they occupied key legislative, judicial, and ministerial roles relating to witchcraft proceedings. Forty six male physicians, surgeons, and apothecaries are named in court transcripts or other contemporary source materials relating to New England witchcraft. These practitioners served on coroners' inquests, performed autopsies, took testimony, issued writs, wrote letters, or committed people to prison, in addition to diagnosing and treating patients.

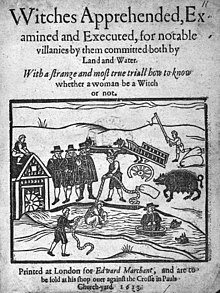

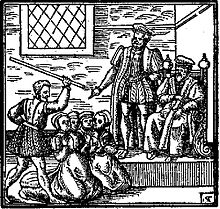

European witch-hunts and witch-trials

In Christianity, sorcery came to be associated with heresy and apostasy and to be viewed as evil. Among the Catholics, Protestants, and secular leadership of the European Late Medieval/Early Modern period, fears about witchcraft rose to fever pitch and sometimes led to large-scale witch-hunts. The key century was the fifteenth, which saw a dramatic rise in awareness and terror of witchcraft, culminating in the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum but prepared by such fanatical popular preachers as Bernardino of Siena. In total, tens or hundreds of thousands of people were executed, and others were imprisoned, tortured, banished, and had lands and possessions confiscated. The majority of those accused were women, though in some regions the majority were men. In early modern Scots, the word warlock came to be used as the male equivalent of witch (which can be male or female, but is used predominantly for females).

The Malleus Maleficarum, (Latin for 'Hammer of The Witches') was a witch-hunting manual written in 1486 by two German monks, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger. It was used by both Catholics and Protestants for several hundred years, outlining how to identify a witch, what makes a woman more likely than a man to be a witch, how to put a witch on trial, and how to punish a witch. The book defines a witch as evil and typically female. The book became the handbook for secular courts throughout Renaissance Europe, but was not used by the Inquisition, which even cautioned against relying on The Work. It is likely that this caused witch mania to become so widespread. It was the most sold book in Europe for over 100 years, after the Bible.

European witch-trials reached their peak in the early 17th century, after which popular sentiment began to turn against the practice. Friedrich Spee's book Cautio Criminalis, published in 1631, argued that witch-trials were largely unreliable and immoral. In 1682, King Louis XIV prohibited further witch-trials in France. In 1736, Great Britain formally ended witch-trials with passage of the Witchcraft Act.

Modern witch-hunts

Belief in witchcraft continues to be present today in some societies and accusations of witchcraft are the trigger for serious forms of violence, including murder. Such incidents are common in countries such as Burkina Faso, Ghana, India, Kenya, Malawi, Nepal and Tanzania. Accusations of witchcraft are sometimes linked to personal disputes, jealousy, and conflicts between neighbors or family members over land or inheritance. Witchcraft-related violence is often discussed as a serious issue in the broader context of violence against women. In Tanzania, about 500 old women are murdered each year following accusations of witchcraft or accusations of being a witch. Apart from extrajudicial violence, state-sanctioned violence also occurs in some jurisdictions. For instance, in Saudi Arabia practicing witchcraft and sorcery is a crime punishable by death and the country has executed people for this crime in 2011, 2012 and 2014.

Children who live in some regions of the world, such as parts of Africa, are also vulnerable to violence that is related to witchcraft accusations. Such incidents have also occurred in immigrant communities in the UK, including the much publicized case of the murder of Victoria Climbié.

Wicca

During the 20th century, interest in witchcraft in English-speaking and European countries began to increase, inspired particularly by Margaret Murray's theory of a pan-European witch-cult originally published in 1921, since discredited by further careful historical research. Interest was intensified, however, by Gerald Gardner's claim in 1954 in Witchcraft Today that a form of witchcraft still existed in England. The truth of Gardner's claim is now disputed too.

The first Neopagan groups to publicly appear, during the 1950s and 60s, were Gerald Gardner's Bricket Wood coven and Roy Bowers' Clan of Tubal Cain. They operated as initiatory secret societies. Other individual practitioners and writers such as Paul Huson also claimed inheritance to surviving traditions of witchcraft.

The Wicca that Gardner initially taught was a witchcraft religion having a lot in common with Margaret Murray's hypothetically posited cult of the 1920s. Indeed, Murray wrote an introduction to Gardner's Witchcraft Today, in effect putting her stamp of approval on it. These Wiccan witches do not adhere to the more common definition of Witchcraft, and generally define their practices as a type of "positive magic." Various forms of Wicca are now practised as a religion of an initiatory secret society nature with positive ethical principles, organised into autonomous covens and led by a High Priesthood. There is also a large "Eclectic Wiccan" movement of individuals and groups who share key Wiccan beliefs but have no initiatory connection or affiliation with traditional Wicca. Wiccan writings and ritual show borrowings from a number of sources including 19th and 20th-century ceremonial magic, the medieval grimoire known as the Key of Solomon, Aleister Crowley's Ordo Templi Orientis and pre-Christian religions. A survey published in November 2000 cited just over 200,000 people who reported practicing Wicca in the United States.

Witchcraft, feminism, and media

Wiccan and Neo-Wiccan literature has been described as aiding the empowerment of young women through its lively portrayal of female protagonists. Part of the recent growth in Neo-Pagan religions has been attributed to the strong media presence of fictional pop culture works such as Charmed, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and the Harry Potter series with their depictions of "positive witchcraft", which differs from the historical, traditional, and Indigenous definitions. Based on a mass media case study done, "Mass Media and Religious Identity: A Case Study of Young Witches", in the result of the case study it was stated the reasons many young people are choosing to self-identify as witches and belong to groups they define as practicing witchcraft is diverse; however, the use of pop culture witchcraft in various media platforms can be the spark of interest for young people to see themselves as "witches". Widespread accessibility to related material through internet media such as chat rooms and forums is also thought to be driving this development. Which is dependent on one's accessibility to those media resources and material to influence their thoughts and views on religion.

Wiccan beliefs, or pop culture variations thereof, are often considered by adherents to be compatible with liberal ideals such as the Green movement, and particularly with some varieties of feminism, by providing young women with what they see as a means for self-empowerment, control of their own lives, and potentially a way of influencing the world around them. This is the case particularly in North America due to the strong presence of feminist ideals in some branches of the Neopagan communities and the long tradition of women-led and women-only groups such as in Dianic Wicca. The 2002 study Enchanted Feminism: The Reclaiming Witches of San Francisco suggests that some branches of Wicca include influential members of the second wave of feminism, which has also been redefined as a religious movement.

Traditional witchcraft

Traditional witchcraft is a term used to refer to a variety of contemporary forms of witchcraft. Pagan studies scholar Ethan Doyle White described it as "a broad movement of aligned magico-religious groups who reject any relation to Gardnerianism and the wider Wiccan movement, claiming older, more "traditional" roots. Although typically united by a shared aesthetic rooted in European folklore, the Traditional Craft contains within its ranks a rich and varied array of occult groups, from those who follow a contemporary Pagan path that is suspiciously similar to Wicca to those who adhere to Luciferianism". According to British Traditional Witch Michael Howard, the term refers to "any non-Gardnerian, non-Alexandrian, non-Wiccan or pre-modern form of the Craft, especially if it has been inspired by historical forms of witchcraft and folk magic". Another definition was offered by Daniel A. Schulke, the current Magister of the Cultus Sabbati, when he proclaimed that traditional witchcraft "refers to a coterie of initiatory lineages of ritual magic, spellcraft and devotional mysticism". Some forms of traditional witchcraft are the Feri Tradition, Cochrane's Craft and the Sabbatic craft.

Stregheria

Modern Stregheria closely resembles Charles Leland's controversial late-19th-century account of a surviving Italian religion of witchcraft, worshipping the Goddess Diana, her brother Dianus/Lucifer, and their daughter Aradia. Leland's witches do not see Lucifer as the evil Satan that Christians see, but a benevolent god of the Sun.

The ritual format of contemporary Stregheria is roughly similar to that of other Neopagan witchcraft religions such as Wicca. The pentagram is the most common symbol of religious identity. Most followers celebrate a series of eight festivals equivalent to the Wiccan Wheel of the Year, though others follow the ancient Roman festivals. An emphasis is placed on ancestor worship and balance.

Witchcraft and Satanism

Demonic associations in general may sometimes implicate witchcraft with the Devil, as conceived variously across different cultures and religious traditions. The character of Satan influenced all Abrahamic religions, and accusations of witchcraft were routinely associated with Satanism. Sometimes under the guise of Lucifer, a more noble characterization developed as a rebellious counterpart to Christianity. In Europe after the Enlightenment, influential works such as Milton's Paradise Lost were described anew by Romantics suggesting the biblical Satan as an allegory representing crisis of faith, individualism, free will, wisdom, and spiritual enlightenment.

In the 20th century, other works presented Satan in a less negative light, such as Letters from the Earth. The 1933 book The God of the Witches by Margaret Murray influenced Herbert Arthur Sloane, who connected the horned god with Satan (Sathanas), and founded the Ophite Cultus Satanas in 1948. Sloane also corresponded with his contemporary Gerald Gardner, founder of modern Wicca, and implied that his views of Satan and the horned god were not necessarily in conflict with Gardner's approach. However, he did believe that, while gnosis referred to knowledge, and Wicca referred to wisdom, modern witches had fallen away from the true knowledge, and instead had begun worshipping a fertility god, a reflection of the creator god. He wrote that "the largest existing body of witches who are true Satanists would be the Yezedees". Sloane highly recommended the book The Gnostic Religion, and sections of it were sometimes read at ceremonies.

Anton LaVey treated Satan not as a literal god, but rather an evocative namesake for The Church of Satan, which he founded in 1966. The Church incorporates magic in their practice, distinguishing between Lesser and Greater forms. LaVey published The Compleat Witch in 1971, subsequently republished as The Satanic Witch. While the Church and other atheistic Satanists use Satan as a symbolic embodiment of certain human traits, there are also theistic Satanists who venerate Satan as a supernatural deity. Contemporary Satanism is mainly an American phenomenon, although it began to reach Eastern Europe in the 1990s around the time of the fall of the Soviet Union.

In the 21st century, witchcraft may still be erroneously associated with ideas of "devil worship" and potentially conflated with contemporary Satanism. Estimates suggest up to 100,000 Satanists worldwide in 2006 (twice the number estimated in 1990). Satanic beliefs have been largely permitted as a valid expression of religious belief in the West. Satanists were allowed in the British Royal Navy in 2004, and an appeal was considered in 2005 for religious status as a right of prisoners by the Supreme Court of the United States. Founded in 2013, the Satanic Temple avoids the practice of magic, claiming "beliefs should conform to one's best scientific understanding of the world."

Luciferianism developed on principles of independence and human progression, a symbol of enlightenment. Madeline Montalban was an English witch who adhered to the veneration of Lucifer, or Lumiel, whom she considered a benevolent angelic being who had aided humanity's development. Within her Order, she emphasised that her followers discover their own personal relationship with the angelic beings, including Lumiel. Although initially seeming favourable to Gerald Gardner, by the mid-1960s she had become hostile towards him and his Gardnerian tradition, considering him to be "a 'dirty old man' and sexual pervert." She also expressed hostility to another prominent Pagan Witch of the period, Charles Cardell, although in the 1960s became friends with the two Witches at the forefront of the Alexandrian Wiccan tradition, Alex Sanders and his wife, Maxine Sanders, who adopted some of her Luciferian angelic practices. In contemporary times Luciferian witches exist within traditional witchcraft.

Historical and religious perspectives

Near East beliefs

The belief in sorcery and its practice seem to have been widespread in the ancient Near East and Nile Valley. It played a conspicuous role in the cultures of ancient Egypt and in Babylonia. The latter tradition included an Akkadian anti-witchcraft ritual, the Maqlû. A section from the Code of Hammurabi (about 2000 B.C.) prescribes:

If a man has put a spell upon another man and it is not justified, he upon whom the spell is laid shall go to the holy river; into the holy river shall he plunge. If the holy river overcome him and he is drowned, the man who put the spell upon him shall take possession of his house. If the holy river declares him innocent and he remains unharmed the man who laid the spell shall be put to death. He that plunged into the river shall take possession of the house of him who laid the spell upon him.

Abrahamic religions

Christianity

Hebrew Bible

According to the New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia:

In the Holy Scripture references to sorcery are frequent, and the strong condemnations of such practices found there do not seem to be based so much upon the supposition of fraud as upon the abomination of the magic in itself.

The King James Version uses the words witch, witchcraft, and witchcrafts to translate the Masoretic כָּשַׁף kāsháf (Hebrew pronunciation: [kɔˈʃaf]) and קֶסֶם (qésem); these same English terms are used to translate φαρμακεία pharmakeia in the Greek New Testament. Verses such as Deuteronomy 18:11–12 and Exodus 22:18 ("Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live") thus provided scriptural justification for Christian witch hunters in the early modern period (see Christian views on magic).

The precise meaning of the Hebrew כָּשַׁף, usually translated as witch or sorceress, is uncertain. In the Septuagint, it was translated as pharmakeía or pharmakous. In the 16th century, Reginald Scot, a prominent critic of the witch trials, translated כָּשַׁף, φαρμακεία, and the Vulgate's Latin equivalent veneficos as all meaning 'poisoner', and on this basis, claimed that witch was an incorrect translation and poisoners were intended. His theory still holds some currency, but is not widely accepted, and in Daniel 2:2 כָּשַׁף is listed alongside other magic practitioners who could interpret dreams: magicians, astrologers, and Chaldeans. Suggested derivations of כָּשַׁף include 'mutterer' (from a single root) or herb user (as a compound word formed from the roots kash, meaning 'herb', and hapaleh, meaning 'using'). The Greek φαρμακεία literally means 'herbalist' or one who uses or administers drugs, but it was used virtually synonymously with mageia and goeteia as a term for a sorcerer.

The Bible provides some evidence that these commandments against sorcery were enforced under the Hebrew kings:

And Saul disguised himself, and put on other raiment, and he went, and two men with him, and they came to the woman by night: and he said, I pray thee, divine unto me by the familiar spirit,[a] and bring me him up, whom I shall name unto thee. And the woman said unto him, Behold, thou knowest what Saul hath done, how he hath cut off those that have familiar spirits, and the wizards, out of the land: wherefore then layest thou a snare for my life, to cause me to die?

New Testament

The New Testament condemns the practice as an abomination, just as the Old Testament had (Galatians 5:20, compared with Revelation 21:8; 22:15; and Acts 8:9; 13:6). The word in most New Testament translations is sorcerer/sorcery rather than witch/witchcraft.

Judaism

Jewish law views the practice of witchcraft as being laden with idolatry and/or necromancy; both being serious theological and practical offenses in Judaism. Although Maimonides vigorously denied the efficacy of all methods of witchcraft, and claimed that the Biblical prohibitions regarding it were precisely to wean the Israelites from practices related to idolatry. It is acknowledged that while magic exists, it is forbidden to practice it on the basis that it usually involves the worship of other gods. Rabbis of the Talmud also condemned magic when it produced something other than illusion, giving the example of two men who use magic to pick cucumbers (Sanhedrin 67a). The one who creates the illusion of picking cucumbers should not be condemned, only the one who actually picks the cucumbers through magic.

However, some of the rabbis practiced "magic" themselves or taught the subject. For instance, Rava (amora) created a golem and sent it to Rav Zeira, and Hanina and Hoshaiah studied every Friday together and created a small calf to eat on Shabbat (Sanhedrin 67b). In these cases, the "magic" was seen more as divine miracles (i.e., coming from God rather than "unclean" forces) than as witchcraft.

Judaism does make it clear that Jews shall not try to learn about the ways of witches (Book of Deuteronomy 18: 9–10) and that witches are to be put to death (Exodus 22:17).

Judaism's most famous reference to a medium is undoubtedly the Witch of Endor whom Saul consults, as recounted in 1 Samuel 28.

Islam

Divination and magic in Islam encompass a wide range of practices, including black magic, warding off the evil eye, the production of amulets and other magical equipment, evocation, casting lots, and astrology.

Legitimacy of practising witchcraft is disputed. Most of Islamic traditions distinguishes magic between good magic and black magic. al-Razi and Ibn Sina, describe that magic is merely a tool and only the outcome determines whether or not the act of magic was legitimate or not. Al-Ghazali, although admitting the reality of magic, regards learning all sorts of magic as forbidden. Ibn al-Nadim argues that good supernatural powers are received from God after purifying the soul, while sorcerers please devils and commit acts of disobedience and sacrifes to demons. Whether or not sorcery is accessed by acts of piety or disobedience is often seen as an indicator whether magic is licit or illicit. Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya, a disciple of Ibn Taimiyya, who became the major source for Wahhabism, disregards magic, including exorcisms, entirely as superstition. Ibn Khaldun brands sorcery, talismans, and prestidigitation as forbidden and illegal. Tabasi did not subscribed to the rationalized framework of magic of most Ash'arite theologians, but only offered a wide range of rituals to perform sorcery. Yet he agrees that only magic in accordance with sharia is permissible. Most of Islamic traditions distinguishes magic between good magic and black magic. Miracles belong to licit magic and are considered gifts of God.

The reality of magic is confirmed by the Quran. The Quran itself is said to bestow magical blessings upon hearers and heal them, based on al-Isra. Solomon had the power to speak with animals and jinn, and command devils, which is only given to him with God's permission.[Quran 27:19] Surah Al-Falaq is used as a prayer to God to ward off black magic and is, according to hadith-literature, revealed to Muhammad to protect him against Jann the ancestor of the jinn. Muhammad was falsely accused of being a magician by his opponents.[Quran 10:2] The idea that devils teach magic is confirmed in Al-Baqara. A pair of fallen angels named Harut and Marut is also mentioned to tempt people into learning sorcery.

Scholars of the history of religion have linked several magical practises in Islam with pre-Islamic Turkish and East African customs. Most notable of these customs is the Zār.

By region

Africa

Much of what witchcraft represents in Africa has been susceptible to misunderstandings and confusion, thanks in no small part to a tendency among western scholars since the time of the now largely discredited Margaret Murray to approach the subject through a comparative lens vis-a-vis European witchcraft.

While some colonialists tried to eradicate witch hunting by introducing legislation to prohibit accusations of witchcraft, some of the countries where this was the case have formally recognized the reality of witchcraft via the law. This has produced an environment that encourages persecution of suspected witches.

Cameroon

In eastern Cameroon, the term used for witchcraft among the Maka is djambe and refers to a force inside a person; its powers may make the proprietor more vulnerable. It encompasses the occult, the transformative, killing and healing.

Central African Republic

Every year, hundreds of people in the Central African Republic are convicted of witchcraft. Christian militias in the Central African Republic have also kidnapped, burnt and buried alive women accused of being 'witches' in public ceremonies.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

As of 2006, between 25,000 and 50,000 children in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, had been accused of witchcraft and thrown out of their homes. These children have been subjected to often-violent abuse during exorcisms, sometimes supervised by self-styled religious pastors. Other pastors and Christian activists strongly oppose such accusations and try to rescue children from their unscrupulous colleagues. The usual term for these children is enfants sorciers ('child witches') or enfants dits sorciers ('children accused of witchcraft'). In 2002, USAID funded the production of two short films on the subject, made in Kinshasa by journalists Angela Nicoara and Mike Ormsby.

In April 2008, in Kinshasa, the police arrested 14 suspected victims (of penis snatching) and sorcerers accused of using black magic or witchcraft to steal (make disappear) or shrink men's penises to extort cash for cure, amid a wave of panic.

According to one study, the belief in magical warfare technologies (such as "bulletproofing") in the Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo serves a group-level function, as it increases group efficiency in warfare, even if it is suboptimal at the individual level. The authors of the study argue that this is one reason why the belief in witchcraft persists.

Complimentary remarks about witchcraft by a native Congolese initiate:

From witchcraft ... may be developed the remedy (kimbuki) that will do most to raise up our country." "Witchcraft ... deserves respect ... it can embellish or redeem (ketula evo vuukisa)." "The ancestors were equipped with the protective witchcraft of the clan (kindoki kiandundila kanda). ... They could also gather the power of animals into their hands ... whenever they needed. ... If we could make use of these kinds of witchcraft, our country would rapidly progress in knowledge of every kind." "You witches (zindoki) too, bring your science into the light to be written down so that ... the benefits in it ... endow our race."

Ghana

In Ghana, women are often accused of witchcraft and attacked by neighbours. Because of this, there exist six witch camps in the country where women suspected of being witches can flee for safety. The witch camps, which exist solely in Ghana, are thought to house a total of around 1000 women. Some of the camps are thought to have been set up over 100 years ago. The Ghanaian government has announced that it intends to close the camps.

Arrests were made in an effort to avoid bloodshed seen in Ghana a decade ago, when 12 alleged penis snatchers were beaten to death by mobs. While it is easy for modern people to dismiss such reports, Uchenna Okeja argues that a belief system in which such magical practices are deemed possible offer many benefits to Africans who hold them. For example, the belief that a sorcerer has "stolen" a man's penis functions as an anxiety-reduction mechanism for men suffering from impotence while simultaneously providing an explanation that is consistent with African cultural beliefs rather than appealing to Western scientific notions that are tainted by the history of colonialism (at least for many Africans).

Kenya

It was reported that a mob in Kenya had burnt to death at least 11 people accused of witchcraft in 2008.

Malawi

In Malawi it is also common practice to accuse children of witchcraft and many children have been abandoned, abused and even killed as a result. As in other African countries both African traditional healers and their Christian counterparts are trying to make a living out of exorcising children and are actively involved in pointing out children as witches. Various secular and Christian organizations are combining their efforts to address this problem.

According to William Kamkwamba, witches and wizards are afraid of money, which they consider a rival evil. Any contact with cash will snap their spell and leave the wizard naked and confused, so placing cash, such as kwacha around a room or bed mat will protect the resident from their malevolent spells.

Nigeria

In Nigeria, several Pentecostal pastors have mixed their evangelical brand of Christianity with African beliefs in witchcraft to benefit from the lucrative witch finding and exorcism business—which in the past was the exclusive domain of the so-called witch doctor or traditional healers. These pastors have been involved in the torturing and even killing of children accused of witchcraft. Over the past decade, around 15,000 children have been accused, and around 1,000 murdered. Churches are very numerous in Nigeria, and competition for congregations is hard. Some pastors attempt to establish a reputation for spiritual power by "detecting" child witches, usually following a death or loss of a job within a family, or an accusation of financial fraud against the pastor. In the course of "exorcisms", accused children may be starved, beaten, mutilated, set on fire, forced to consume acid or cement, or buried alive. While some church leaders and Christian activists have spoken out strongly against these abuses, many Nigerian churches are involved in the abuse, although church administrations deny knowledge of it.

In May 2020, fifteen adults, mostly women, were set ablaze after being accused of witchcraft, including the mother of the instigator of the attack, Thomas Obi Tawo, a local politician.

Sierra Leone

Among the Mende (of Sierra Leone), trial and conviction for witchcraft has a beneficial effect for those convicted. "The witchfinder had warned the whole village to ensure the relative prosperity of the accused and sentenced ... old people. ... Six months later all of the people ... accused, were secure, well-fed and arguably happier than at any [previous] time; they had hardly to beckon and people would come with food or whatever was needful. ... Instead of such old and widowed people being left helpless or (as in Western society) institutionalized in old people's homes, these were reintegrated into society and left secure in their old age ... Old people are 'suitable' candidates for this kind of accusation in the sense that they are isolated and vulnerable, and they are 'suitable' candidates for 'social security' for precisely the same reasons." In Kuranko language, the term for witchcraft is suwa'ye referring to 'extraordinary powers'.

Tanzania

In Tanzania in 2008, President Kikwete publicly condemned witchdoctors for killing albinos for their body parts, which are thought to bring good luck. 25 albinos have been murdered since March 2007. In Tanzania, albinos are often murdered for their body parts on the advice of witch doctors in order to produce powerful amulets that are believed to protect against witchcraft and make the owner prosper in life.

Zulu

Native to the Zulu people, witches called sangoma protect people against evil spirits. They usually train for about five to seven years. In the cities, this training could take only several months.

Another type of witch are the inyanga, who are actual witch doctors that heal people with plant and animal parts. This is a job that is passed on to future generations. In the Zulu population, 80% of people contact inyangas.

Americas

British America

In 1645, Springfield, Massachusetts, experienced America's first accusations of witchcraft when husband and wife Hugh and Mary Parsons accused each other of witchcraft. At America's first witch trial, Hugh was found innocent, while Mary was acquitted of witchcraft but sentenced to be hanged for the death of her child. She died in prison. From 1645 to 1663, about eighty people throughout England's Massachusetts Bay Colony were accused of practicing witchcraft. Thirteen women and two men were executed in a witch-hunt that lasted throughout New England from 1645 to 1663. The Salem witch trials followed in 1692–93. These witch trials were the most famous in British North America and took place in the coastal settlements near Salem, Massachusetts. Prior to the witch trials, nearly 300 men and women had been suspected of partaking in witchcraft, and 19 of these people were hanged, and one was "pressed to death".

Despite being generally known as the Salem witch trials, the preliminary hearings in 1692 were conducted in a variety of towns across the province: Salem Village (now Danvers), Salem Town, Ipswich, and Andover. The best known trials were conducted by the Court of Oyer and Terminer in 1692 in Salem Town. In Maryland, there is a legend of Moll Dyer, who escaped a fire set by fellow colonists only to die of exposure in December 1697. The historical record of Dyer is scant as all official records were burned in a courthouse fire, though the county courthouse has on display the rock where her frozen body was found. A letter from a colonist of the period describes her in most unfavourable terms. A local road is named after Dyer, where her homestead was said to have been. Many local families have their own version of the Moll Dyer affair, and her name is spoken with care in the rural southern counties. Accusations of witchcraft and wizardry led to the prosecution of a man in Tennessee as recently as 1833. The Crucible by Arthur Miller is a dramatized and partially fictionalized story of the Salem witch trials that took place in the Massachusetts Bay Colony during 1692–93.

Latin America

Bruja is an Afro-Caribbean religion and healing tradition that originates in Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao, in the Dutch Caribbean. A healer in this culture is called a kurioso or kuradó, a man or woman who performs trabou chikí ('little works') and trabou grandi ('large treatments') to promote or restore health, bring fortune or misfortune, deal with unrequited love, and more serious concerns, in which sorcery is involved. Sorcery usually involves reference to the almasola or homber chiki, a devil-like entity. Transcultural Psychiatry published a paper called "Traditional healing practices originating in Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao: A review of the literature on psychiatry and Brua" by Jan Dirk Blom, Igmar T. Poulina, Trevor L. van Gellecum and Hans W. Hoek of the Parnassia Psychiatric Institute.

Witchcraft was an important part of the social and cultural history of late-Colonial Mexico, during the Mexican Inquisition. Spanish Inquisitors viewed witchcraft as a problem that could be cured simply through confession. Yet, as anthropologist Ruth Behar writes, witchcraft, not only in Mexico but in Latin America in general, was a "conjecture of sexuality, witchcraft, and religion, in which Spanish, indigenous, and African cultures converged." Furthermore, witchcraft in Mexico generally required an interethnic and interclass network of witches. Yet, according to anthropology professor Laura Lewis, witchcraft in colonial Mexico ultimately represented an "affirmation of hegemony" for women, Indians, and especially Indian women over their white male counterparts as a result of the casta system.

The presence of the witch is a constant in the ethnographic history of colonial Brazil, especially during the several denunciations and confessions given to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith of Bahia (1591–1593), Pernambuco and Paraíba (1593–1595).

The yee naaldlooshii is the type of witch known in English as a skin-walker. They are believed to take the forms of animals in order to travel in secret and do harm to the innocent. In the Navajo language, yee naaldlooshii translates to 'with it, he goes on all fours'. While perhaps the most common variety seen in horror fiction by non-Navajo people, the yee naaldlooshii is one of several varieties of Navajo witch, specifically a type of 'ánti'įhnii.

Corpse powder or corpse poison (Navajo: áńt'į́, literally 'witchery' or 'harming') is a substance made from powdered corpses. The powder is used by witches to curse their victims.

Traditional Navajos usually hesitate to discuss things like witches and witchcraft with non-Navajos.

Asia

India

Belief in the supernatural is strong in all parts of India, and lynchings for witchcraft are reported in the press from time to time. Around 750 people were killed as witches in Assam and West Bengal between 2003 and 2008. Officials in the state of Chhattisgarh reported in 2008 that at least 100 women are maltreated annually as suspected witches. A local activist stated that only a fraction of cases of abuse are reported. In Indian mythology, a common perception of a witch is a being with her feet pointed backwards.

Nepal

In Nepali language, witches are known as Boksi (Nepali: बोक्सी). Apart from other types of Violence against women in Nepal, the malpractice of abusing women in the name of witchcraft is also prominent. According to the statistics in 2013, there was a total of 69 reported cases of abuse to women due to accusation of performing witchcraft. The perpetrators of this malpractice are usually neighbors, so-called witch doctors and family members. The main causes of these malpractices are lack of education, lack of awareness and superstition. According to the statistics by INSEC, the age group of women who fall victims to the witchcraft violence in Nepal is 20–40.

Japan

In Japanese folklore, the most common types of witch can be separated into two categories: those who employ snakes as familiars, and those who employ foxes. The fox witch is, by far, the most commonly seen witch figure in Japan. Differing regional beliefs set those who use foxes into two separate types: the kitsune-mochi, and the tsukimono-suji. The first of these, the kitsune-mochi, is a solitary figure who gains his fox familiar by bribing it with its favourite foods. The kitsune-mochi then strikes up a deal with the fox, typically promising food and daily care in return for the fox's magical services. The fox of Japanese folklore is a powerful trickster in and of itself, imbued with powers of shape changing, possession, and illusion. These creatures can be either nefarious; disguising themselves as women in order to trap men, or they can be benign forces as in the story of "The Grateful foxes". By far, the most commonly reported cases of fox witchcraft in modern Japan are enacted by tsukimono-suji families, or 'hereditary witches'.

Philippines

In the Philippines, as in many of these cultures, witches are viewed as those opposed to the sacred. In contrast, anthropologists writing about the healers in Indigenous Philippine folk religions either use the traditional terminology of these cultures, or broad anthropological terms like shaman.

Philippine witches are the users of black magic and related practices from the Philippines. They include a variety of different kinds of people with differing occupations and cultural connotations which depend on the ethnic group they are associated with. They are completely different from the Western notion of what a witch is, as each ethnic group has their own definition and practices attributed to witches. The curses and other magics of witches are often blocked, countered, cured, or lifted by Philippine shamans associated with the indigenous Philippine folk religions.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia continues to use the death penalty for sorcery and witchcraft. In 2006 Fawza Falih Muhammad Ali was condemned to death for practicing witchcraft. There is no legal definition of sorcery in Saudi, but in 2007 an Egyptian pharmacist working there was accused, convicted, and executed. Saudi authorities also pronounced the death penalty on a Lebanese television presenter, Ali Hussain Sibat, while he was performing the hajj (Islamic pilgrimage) in the country.

In 2009, the Saudi authorities set up the Anti-Witchcraft Unit of their Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice police. In April 2009, a Saudi woman Amina Bint Abdulhalim Nassar was arrested and later sentenced to death for practicing witchcraft and sorcery. In December 2011, she was beheaded. A Saudi man has been beheaded on charges of sorcery and witchcraft in June 2012. A beheading for sorcery occurred in 2014.

Islamic State

In June 2015, Yahoo reported: "The Islamic State group has beheaded two women in Syria on accusations of 'sorcery', the first such executions of female civilians in Syria, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said Tuesday."

Europe

Witchcraft in Europe between 500 and 1750 was believed to be a combination of sorcery and heresy. While sorcery attempts to produce negative supernatural effects through formulas and rituals, heresy is the Christian contribution to witchcraft in which an individual makes a pact with the Devil. In addition, heresy denies witches the recognition of important Christian values such as baptism, salvation, Christ and sacraments. The beginning of the witch accusations in Europe took place in the 14th and 15th centuries; however as the social disruptions of the 16th century took place, witchcraft trials intensified.

In Early Modern European tradition, witches were stereotypically, though not exclusively, women. European pagan belief in witchcraft was associated with the goddess Diana and dismissed as "diabolical fantasies" by medieval Christian authors. Witch-hunts first appeared in large numbers in southern France and Switzerland during the 14th and 15th centuries. The peak years of witch-hunts in southwest Germany were from 1561 to 1670.

It was commonly believed that individuals with power and prestige were involved in acts of witchcraft and even cannibalism. Because Europe had a lot of power over individuals living in West Africa, Europeans in positions of power were often accused of taking part in these practices. Though it is not likely that these individuals were actually involved in these practices, they were most likely associated due to Europe's involvement in things like the slave trade, which negatively affected the lives of many individuals in the Atlantic World throughout the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries.

Early converts to Christianity looked to Christian clergy to work magic more effectively than the old methods under Roman paganism, and Christianity provided a methodology involving saints and relics, similar to the gods and amulets of the Pagan world. As Christianity became the dominant religion in Europe, its concern with magic lessened.

The Protestant Christian explanation for witchcraft, such as those typified in the confessions of the Pendle witches, commonly involves a diabolical pact or at least an appeal to the intervention of the spirits of evil. The witches or wizards engaged in such practices were alleged to reject Jesus and the sacraments; observe "the witches' sabbath" (performing infernal rites that often parodied the Mass or other sacraments of the Church); pay Divine honour to the Prince of Darkness; and, in return, receive from him preternatural powers. It was a folkloric belief that a Devil's Mark, like the brand on cattle, was placed upon a witch's skin by the devil to signify that this pact had been made.

Britain

In the north of England, the superstition lingers to an almost inconceivable extent. Lancashire abounds with witch-doctors, a set of quacks, who pretend to cure diseases inflicted by the devil ... The witch-doctor alluded to is better known by the name of the cunning man, and has a large practice in the counties of Lincoln and Nottingham.

Historians Keith Thomas and his student Alan Macfarlane study witchcraft by combining historical research with concepts drawn from anthropology. They argued that English witchcraft, like African witchcraft, was endemic rather than epidemic. Old women were the favorite targets because they were marginal, dependent members of the community and therefore more likely to arouse feelings of both hostility and guilt, and less likely to have defenders of importance inside the community. Witchcraft accusations were the village's reaction to the breakdown of its internal community, coupled with the emergence of a newer set of values that was generating psychic stress.

In Wales, fear of witchcraft mounted around the year 1500. There was a growing alarm of women's magic as a weapon aimed against the state and church. The Church made greater efforts to enforce the canon law of marriage, especially in Wales where tradition allowed a wider range of sexual partnerships. There was a political dimension as well, as accusations of witchcraft were levied against the enemies of Henry VII, who was exerting more and more control over Wales. In 1542, the first of many Witchcraft Acts was passed defining witchcraft as a crime punishable by death and the forfeiture of property.

The records of the Courts of Great Sessions for Wales, 1536–1736 show that Welsh custom was more important than English law. Custom provided a framework of responding to witches and witchcraft in such a way that interpersonal and communal harmony was maintained. Even when found guilty, execution did not occur.

Becoming king in 1567, James VI and I brought to England and Scotland continental explanations of witchcraft. His goal was to divert suspicion away from male homosociality among the elite, and focus fear on female communities and large gatherings of women. He thought they threatened his political power so he laid the foundation for witchcraft and occultism policies, especially in Scotland. The point was that a widespread belief in the conspiracy of witches and a witches' Sabbath with the devil deprived women of political influence. Occult power was supposedly a womanly trait because women were weaker and more susceptible to the devil.

The last person executed for witchcraft in Great Britain was Janet Horne in 1727. The Witchcraft Act 1735 abolished the penalty of execution for witchcraft, replacing it with imprisonment. This act was repealed in 1951.

In the United Kingdom children believed to be witches or seen as possessed by evil spirits can be subject to severe beatings, traumatic exorcism, and/or other abuse. There have even been child murders associated with witchcraft beliefs. The problem is particularly serious among immigrant or former immigrant communities of African origin but other communities, such as those of Asian origin are also involved. Step children and children seen as different for a wide range of reasons are particularly at risk of witchcraft accusations. Children may be beaten or have chilli rubbed into their eyes during exorcisms. This type of abuse is frequently hidden and can include torture. A 2006 recommendation to record abuse cases linked to witchcraft accusations centrally has not yet been implemented. Lack of awareness among social workers, teachers and other professionals dealing with at risk children hinders efforts to combat the problem.

The Metropolitan Police said there had been 60 crimes linked to faith in London so far [in 2015]. It saw reports double from 23 in 2013 to 46 in 2014. Half of UK police forces do not record such cases and many local authorities are also unable to provide figures. The NSPCC said authorities "need to ensure they are able to spot the signs of this particular brand of abuse". London is unique in having a police team, Project Violet, dedicated to this type of abuse. Its figures relate to crime reports where officers have flagged a case as involving abuse linked to faith or belief. Many of the cases involve children. (...) An NSPCC spokesman said: "While the number of child abuse cases involving witchcraft is relatively small, they often include horrifying levels of cruelty. "The authorities which deal with these dreadful crimes need to ensure they are able to spot the signs of this particular brand of abuse and take action to protect children before a tragedy occurs."

There is a 'money making scam' involved. Pastors accuse a child of being a witch and later the family pays for exorcism. If a child at school says that his/her pastor called the child a witch that should become a child safeguarding issue.

Italy

A particularly rich source of information about witchcraft in Italy before the outbreak of the Great Witch Hunts of the Renaissance are the sermons of Franciscan popular preacher, Bernardino of Siena (1380–1444), who saw the issue as one of the most pressing moral and social challenges of his day and thus preached many a sermon on the subject, inspiring many local governments to take actions against what he called "servants of the Devil." As in most European countries, women in Italy were more likely suspected of witchcraft than men. Women were considered dangerous due to their supposed sexual instability, such as when being aroused, and also due to the powers of their menstrual blood.

In the 16th century, Italy had a high portion of witchcraft trials involving love magic. The country had a large number of unmarried people due to men marrying later in their lives during this time. This left many women on a desperate quest for marriage leaving them vulnerable to the accusation of witchcraft whether they took part in it or not. Trial records from the Inquisition and secular courts discovered a link between prostitutes and supernatural practices. Professional prostitutes were considered experts in love and therefore knew how to make love potions and cast love related spells. Up until 1630, the majority of women accused of witchcraft were prostitutes. A courtesan was questioned about her use of magic due to her relationship with men of power in Italy and her wealth. The majority of women accused were also considered "outsiders" because they were poor, had different religious practices, spoke a different language, or simply from a different city/town/region. Cassandra from Ferrara, Italy, was still considered a foreigner because not native to Rome where she was residing. She was also not seen as a model citizen because her husband was in Venice.

From the 16th-18th centuries, the Catholic Church enforced moral discipline throughout Italy. With the help of local tribunals, such as in Venice, the two institutions investigated a woman's religious behaviors when she was accused of witchcraft.

Spain

Franciscan friars from New Spain introduced Diabolism, belief in the devil, to the indigenous people after their arrival in 1524. Bartolomé de las Casas believed that human sacrifice was not diabolic, in fact far off from it, and was a natural result of religious expression. Mexican Indians gladly took in the belief of Diabolism and still managed to keep their belief in creator-destroyer deities.

Galicia is nicknamed the "Land of the Witches" due to its mythological origins surrounding its people, culture and its land. The Basque Country also suffered persecutions against witches, such as the case of the Witches of Zugarramurdi, six of which were burned in Logroño in 1610 or the witch hunt in the French Basque country in the previous year with the burning of eighty supposed witches at the stake. This is reflected in the studies of José Miguel de Barandiarán and Julio Caro Baroja. Euskal Herria retains numerous legends that account for an ancient mythology of witchcraft. The town of Zalla is nicknamed "Town of the Witches".

Oceania

Cook Islands

In pre-Christian times, witchcraft was a common practice in the Cook Islands. The native name for a sorcerer was tangata purepure (a man who prays). The prayers offered by the ta'unga (priests) to the gods worshiped on national or tribal marae (temples) were termed karakia; those on minor occasions to the lesser gods were named pure. All these prayers were metrical, and were handed down from generation to generation with the utmost care. There were prayers for every such phase in life; for success in battle; for a change in wind (to overwhelm an adversary at sea, or that an intended voyage be propitious); that his crops may grow; to curse a thief; or wish ill-luck and death to his foes. Few men of middle age were without a number of these prayers or charms. The succession of a sorcerer was from father to son, or from uncle to nephew. So too of sorceresses: it would be from mother to daughter, or from aunt to niece. Sorcerers and sorceresses were often slain by relatives of their supposed victims.

A singular enchantment was employed to kill off a husband of a pretty woman desired by someone else. The expanded flower of a Gardenia was stuck upright—a very difficult performance—in a cup (i.e., half a large coconut shell) of water. A prayer was then offered for the husband's speedy death, the sorcerer earnestly watching the flower. Should it fall the incantation was successful. But if the flower still remained upright, he will live. The sorcerer would in that case try his skill another day, with perhaps better success.

According to Beatrice Grimshaw, a journalist who visited the Cook Islands in 1907, the uncrowned Queen Makea was believed to have possessed the mystic power called mana, giving the possessor the power to slay at will. It also included other gifts, such as second sight to a certain extent, the power to bring good or evil luck, and the ability already mentioned to deal death at will.

Papua New Guinea

A local newspaper informed that more than 50 people were killed in two Highlands provinces of Papua New Guinea in 2008 for allegedly practicing witchcraft. An estimated 50–150 alleged witches are killed each year in Papua New Guinea.

Slavic Russia

Among the Russian words for witch, ведьма (ved'ma) literally means 'one who knows', from Old Slavic вѣдъ 'to know'.

Spells

Pagan practices formed a part of Russian and Eastern Slavic culture; the Russian people were deeply superstitious. The witchcraft practiced consisted mostly of earth magic and herbology; it was not so significant which herbs were used in practices, but how these herbs were gathered. Ritual centered on harvest of the crops and the location of the sun was very important. One source, pagan author Judika Illes, tells that herbs picked on Midsummer's Eve were believed to be most powerful, especially if gathered on Bald Mountain near Kiev during the witches' annual revels celebration. Botanicals should be gathered, "During the seventeenth minute of the fourteenth hour, under a dark moon, in the thirteenth field, wearing a red dress, pick the twelfth flower on the right."

Spells also served for midwifery, shape-shifting, keeping lovers faithful, and bridal customs. Spells dealing with midwifery and childbirth focused on the spiritual wellbeing of the baby. Shape-shifting spells involved invocation of the wolf as a spirit animal. To keep men faithful, lovers would cut a ribbon the length of his erect penis and soak it in his seminal emissions after sex while he was sleeping, then tie seven knots in it; keeping this talisman of knot magic ensured loyalty. Part of an ancient pagan marriage tradition involved the bride taking a ritual bath at a bathhouse before the ceremony. Her sweat would be wiped from her body using raw fish, and the fish would be cooked and fed to the groom.

Demonism, or black magic, was not prevalent. Persecution for witchcraft, mostly involved the practice of simple earth magic, founded on herbology, by solitary practitioners with a Christian influence. In one case investigators found a locked box containing something bundled in a kerchief and three paper packets, wrapped and tied, containing crushed grasses. Most rituals of witchcraft were very simple—one spell of divination consists of sitting alone outside meditating, asking the earth to show one's fate.

While these customs were unique to Russian culture, they were not exclusive to this region. Russian pagan practices were often akin to paganism in other parts of the world. The Chinese concept of chi, a form of energy that often manipulated in witchcraft, is known as bioplasma in Russian practices. The western concept of an "evil eye" or a "hex" was translated to Russia as a "spoiler". A spoiler was rooted in envy, jealousy and malice. Spoilers could be made by gathering bone from a cemetery, a knot of the target's hair, burned wooden splinters and several herb Paris berries (which are very poisonous). Placing these items in sachet in the victim's pillow completes a spoiler. The Sumerians, Babylonians, Assyrians, and the ancient Egyptians recognized the evil eye from as early as 3,000 BCE; in Russian practices it is seen as a sixteenth-century concept.

Societal view of witchcraft

The dominant societal concern those practicing witchcraft was not whether paganism was effective, but whether it could cause harm. Peasants in Russian and Ukrainian societies often shunned witchcraft, unless they needed help against supernatural forces. Impotence, stomach pains, barrenness, hernias, abscesses, epileptic seizures, and convulsions were all attributed to evil (or witchcraft). This is reflected in linguistics; there are numerous words for a variety of practitioners of paganism-based healers. Russian peasants referred to a witch as a chernoknizhnik (a person who plied his trade with the aid of a black book), sheptun/sheptun'ia (a 'whisperer' male or female), lekar/lekarka or znakhar/znakharka (a male or female healer), or zagovornik (an incanter).

Ironically enough, there was universal reliance on folk healers – but clients often turned them in if something went wrong. According to Russian historian Valerie A. Kivelson, witchcraft accusations were normally thrown at lower-class peasants, townspeople and Cossacks. People turned to witchcraft as a means to support themselves. The ratio of male to female accusations was 75% to 25%. Males were targeted more, because witchcraft was associated with societal deviation. Because single people with no settled home could not be taxed, males typically had more power than women in their dissent.

The history of Witchcraft had evolved around society. More of a psychological concept to the creation and usage of Witchcraft can create the assumption as to why women are more likely to follow the practices behind Witchcraft. Identifying with the soul of an individual's self is often deemed as "feminine" in society. There is analyzed social and economic evidence to associate between witchcraft and women.

Russian witch trials

Witchcraft trials frequently occurred in seventeenth-century Russia, although the "great witch-hunt" is believed to be a predominantly Western European phenomenon. However, as the witchcraft-trial craze swept across Catholic and Protestant countries during this time, Orthodox Christian Europe indeed partook in this so-called "witch hysteria." This involved the persecution of both males and females who were believed to be practicing paganism, herbology, the black art, or a form of sorcery within and/or outside their community. Very early on witchcraft legally fell under the jurisdiction of the ecclesiastical body, the church, in Kievan Rus' and Muscovite Russia. Sources of ecclesiastical witchcraft jurisdiction date back as early as the second half of the eleventh century, one being Vladimir the Great's first edition of his State Statute or Ustav, another being multiple references in the Primary Chronicle beginning in 1024.

The sentence for an individual who was found guilty of witchcraft or sorcery during this time, as well as in previous centuries, typically included either burning at the stake or being tested with the "ordeal of cold water" or judicium aquae frigidae. The cold-water test was primarily a Western European phenomenon, but it was also used as a method of truth in Russia both prior to, and post, seventeenth-century witchcraft trials in Muscovy. Accused persons who submerged were considered innocent, and ecclesiastical authorities would proclaim them "brought back", but those who floated were considered guilty of practicing witchcraft, and they were either burned at the stake or executed in an unholy fashion. The thirteenth-century bishop of Vladimir, Serapion Vladimirskii, preached sermons throughout the Muscovite countryside, and in one particular sermon revealed that burning was the usual punishment for witchcraft, but more often the cold water test was used as a precursor to execution.

Although these two methods of torture were used in the west and the east, Russia implemented a system of fines payable for the crime of witchcraft during the seventeenth century. Thus, even though torture methods in Muscovy were on a similar level of harshness as Western European methods used, a more civil method was present. In the introduction of a collection of trial records pieced together by Russian scholar Nikolai Novombergsk, he argues that Muscovite authorities used the same degree of cruelty and harshness as Western European Catholic and Protestant countries in persecuting witches. By the mid-sixteenth century the manifestations of paganism, including witchcraft, and the black arts—astrology, fortune telling, and divination—became a serious concern to the Muscovite church and state.

Tsar Ivan IV (reigned 1547–1584) took this matter to the ecclesiastical court and was immediately advised that individuals practicing these forms of witchcraft should be excommunicated and given the death penalty. Ivan IV, as a true believer in witchcraft, was deeply convinced that sorcery accounted for the death of his wife, Anastasiia in 1560, which completely devastated and depressed him, leaving him heartbroken. Stemming from this belief, Ivan IV became majorly concerned with the threat of witchcraft harming his family, and feared he was in danger. So, during the Oprichnina (1565–1572), Ivan IV succeeded in accusing and charging a good number of boyars with witchcraft whom he did not wish to remain as nobles. Rulers after Ivan IV, specifically during the Time of Troubles (1598–1613), increased the fear of witchcraft among themselves and entire royal families, which then led to further preoccupation with the fear of prominent Muscovite witchcraft circles.

After the Time of Troubles, seventeenth-century Muscovite rulers held frequent investigations of witchcraft within their households, laying the groundwork, along with previous tsarist reforms, for widespread witchcraft trials throughout the Muscovite state. Between 1622 and 1700 ninety-one people were brought to trial in Muscovite courts for witchcraft. Although Russia did partake in the witch craze that swept across Western Europe, the Muscovite state did not persecute nearly as many people for witchcraft, let alone execute a number of individuals anywhere close to the number executed in the west during the witch hysteria.

Witches in art

Witches have a long history of being depicted in art, although most of their earliest artistic depictions seem to originate in Early Modern Europe, particularly the Medieval and Renaissance periods. Many scholars attribute their manifestation in art as inspired by texts such as Canon Episcopi, a demonology-centered work of literature, and Malleus Maleficarum, a "witch-craze" manual published in 1487, by Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger.

Canon Episcopi, a ninth-century text that explored the subject of demonology, initially introduced concepts that would continuously be associated with witches, such as their ability to fly or their believed fornication and sexual relations with the devil. The text refers to two women, Diana the Huntress and Herodias, who both express the duality of female sorcerers. Diana was described as having a heavenly body and as the "protectress of childbirth and fertility" while Herodias symbolized "unbridled sensuality". They thus represent the mental powers and cunning sexuality that witches used as weapons to trick men into performing sinful acts which would result in their eternal punishment. These characteristics were distinguished as Medusa-like or Lamia-like traits when seen in any artwork (Medusa's mental trickery was associated with Diana the Huntress's psychic powers and Lamia was a rumored female figure in the Medieval ages sometimes used in place of Herodias).

One of the first individuals to regularly depict witches after the witch-craze of the medieval period was Albrecht Dürer, a German Renaissance artist. His famous 1497 engraving The Four Witches, portrays four physically attractive and seductive nude witches. Their supernatural identities are emphasized by the skulls and bones lying at their feet as well as the devil discreetly peering at them from their left. The women's sensuous presentation speaks to the overtly sexual nature they were attached to in early modern Europe. Moreover, this attractiveness was perceived as a danger to ordinary men who they could seduce and tempt into their sinful world. Some scholars interpret this piece as utilizing the logic of the Canon Episcopi, in which women used their mental powers and bodily seduction to enslave and lead men onto a path of eternal damnation, differing from the unattractive depiction of witches that would follow in later Renaissance years.

Dürer also employed other ideas from the Middle Ages that were commonly associated with witches. Specifically, his art often referred to former 12th- to 13th-century Medieval iconography addressing the nature of female sorcerers. In the Medieval period, there was a widespread fear of witches, accordingly producing an association of dark, intimidating characteristics with witches, such as cannibalism (witches described as "[sucking] the blood of newborn infants") or described as having the ability to fly, usually on the back of black goats. As the Renaissance period began, these concepts of witchcraft were suppressed, leading to a drastic change in the sorceress' appearances, from sexually explicit beings to the 'ordinary' typical housewives of this time period. This depiction, known as the 'Waldensian' witch became a cultural phenomenon of early Renaissance art. The term originates from the 12th-century monk Peter Waldo, who established his own religious sect which explicitly opposed the luxury and commodity-influenced lifestyle of the Christian church clergy, and whose sect was excommunicated before being persecuted as "practitioners of witchcraft and magic".

Subsequent artwork exhibiting witches tended to consistently rely on cultural stereotypes about these women. These stereotypes were usually rooted in early Renaissance religious discourse, specifically the Christian belief that an "earthly alliance" had taken place between Satan's female minions who "conspired to destroy Christendom".