A blacklight, also referred to as a UV-A light, Wood's lamp, or ultraviolet light, is a lamp that emits long-wave (UV-A) ultraviolet light and very little visible light.

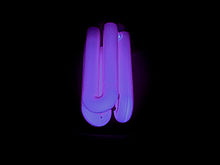

One type of lamp has a violet filter material, either on the bulb or in a separate glass filter in the lamp housing, which blocks most visible light and allows through UV, so the lamp has a dim violet glow when operating. Blacklight lamps which have this filter have a lighting industry designation that includes the letters "BLB". This stands for "blacklight blue".

A second type of lamp produces ultraviolet but does not have the filter material, so it produces more visible light and has a blue color when operating. These tubes are made for use in "bug zapper" insect traps, and are identified by the industry designation "BL". This stands for "blacklight".

Blacklight sources may be specially designed fluorescent lamps, mercury-vapor lamps, light-emitting diodes (LEDs), lasers, or incandescent lamps; although incandescents produce almost no blacklight (except slightly more for halogen types), and so are not considered true blacklight sources. In medicine, forensics, and some other scientific fields, such a light source is referred to as a Wood's lamp, named after Robert Williams Wood, who invented the original Wood's glass UV filters.

Although many other types of lamp emit ultraviolet light with visible light, black lights are essential when UV-A light without visible light is needed, particularly in observing fluorescence, the colored glow that many substances emit when exposed to UV. Black lights are employed for decorative and artistic lighting effects, diagnostic and therapeutic uses in medicine, the detection of substances tagged with fluorescent dyes, rock-hunting, the detection of counterfeit money, the curing of plastic resins, attracting insects and the detection of refrigerant leaks affecting refrigerators and air conditioning systems. Strong sources of long-wave ultraviolet light are used in tanning beds.

UV-A presents a potential hazard when eyes and skin are exposed, especially to high power sources. According to the World Health Organization, UV-A is responsible for the initial tanning of skin and it contributes to skin ageing and wrinkling. UV-A may also contribute to the progression of skin cancers. Additionally, UV-A can have negative effects on eyes in both the short-term and long-term.

Types

Fluorescent

Fluorescent black light tubes are typically made in the same fashion as normal fluorescent tubes except that a phosphor that emits UVA light instead of visible white light is used. The type most commonly used for black lights, designated blacklight blue or "BLB" by the industry, has a dark blue filter coating on the tube, which filters out most visible light, so that fluorescence effects can be observed.

These tubes have a dim violet glow when operating. They should not be

confused with "blacklight" or "BL" tubes, which have no filter coating,

and have a brighter blue color. These are made for use in "bug zapper"

insect traps where the emission of visible light does not interfere

with the performance of the product. The phosphor typically used for a

near 368 to 371 nanometer emission peak is either europium-doped strontium fluoroborate (SrB

2F

8:Eu2+

) or europium-doped strontium borate (Sr

3B

2O

6:Eu2+

) while the phosphor used to produce a peak around 350 to 353 nanometres is lead-doped barium silicate (BaSi

2O

5:Pb+

). "Blacklight blue" lamps peak at 365 nm.

Manufacturers use different numbering systems for black light tubes. Philips uses one system which is becoming outdated (2010), while the (German) Osram system is becoming dominant outside North America. The following table lists the tubes generating blue, UVA and UVB, in order of decreasing wavelength of the most intense peak. Approximate phosphor compositions, major manufacturer's type numbers and some uses are given as an overview of the types available. "Peak" position is approximated to the nearest 10 nm. "Width" is the measure between points on the shoulders of the peak that represent 50% intensity.

| Phosphor Mixture |

Peak (nm) |

Width (nm) |

Philips suffix |

Osram suffix |

U.S. Type | Typical use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | 450 | 50 | — | /71 | — | hyperbilirubinaemia, polymerization |

| SrP 2O 7:Eu |

420 | 30 | /03 | /72 | — | photochemical polymerization |

| SrB 4O 7:Eu |

370 | 20 | /08 | /73 | ("BLB") | forensics, lapidary, night clubs |

| SrB 4O 7:Eu |

370 | 20 | — | /78 | ("BY") | insect attraction, polymerization, psoriasis, tanning beds |

| BaSi 2O 5:Pb |

350 | 40 | /09 | /79 | "BL" | insect attraction, tanning beds |

| BaSi 2O 5:Pb |

350 | 40 | /08 | — | "BLB" | dermatology, lapidary, forensics, night clubs |

| SrAl 11O 18:Ce |

340 | 30 | — | — | — | photochemistry |

| MgSrAl 10O 17:Ce |

310 | 40 | — | — | — | medical applications, polymerization |

"Bug zapper" tubes

Another class of UV fluorescent bulb is designed for use in "bug zapper" flying insect traps. Insects are attracted to the UV light, which they are able to see, and are then electrocuted by the device. These bulbs use the same UV-A emitting phosphor blend as the filtered blacklight, but since they do not need to suppress visible light output, they do not use a purple filter material in the bulb. Plain glass blocks out less of the visible mercury emission spectrum, making them appear light blue-violet to the naked eye. These lamps are referred to by the designation "blacklight" or "BL" in some North American lighting catalogs. These types are not suitable for applications which require the low visible light output of "BLB" tubes lamps.

Incandescent

A black light may also be formed by simply using a UV filter coating such as Wood's glass on the envelope of a common incandescent bulb. This was the method that was used to create the very first black light sources. Although incandescent black light bulbs are a cheaper alternative to fluorescent tubes, they are exceptionally inefficient at producing UV light since most of the light emitted by the filament is visible light which must be blocked. Due to its black body spectrum, an incandescent light radiates less than 0.1% of its energy as UV light. Incandescent UV bulbs, due to the necessary absorption of the visible light, become very hot during use. This heat is, in fact, encouraged in such bulbs, since a hotter filament increases the proportion of UVA in the black-body radiation emitted. This high running-temperature drastically reduces the life of the lamp, however, from a typical 1,000 hours to around 100 hours.

Mercury vapor

High power mercury vapor black light lamps are made in power ratings of 100 to 1,000 watts. These do not use phosphors, but rely on the intensified and slightly broadened 350–375 nm spectral line of mercury from high pressure discharge at between 5 and 10 standard atmospheres (500 and 1,000 kPa), depending upon the specific type. These lamps use envelopes of Wood's glass or similar optical filter coatings to block out all the visible light and also the short wavelength (UVC) lines of mercury at 184.4 and 253.7 nm, which are harmful to the eyes and skin. A few other spectral lines, falling within the pass band of the Wood's glass between 300 and 400 nm, contribute to the output. These lamps are used mainly for theatrical purposes and concert displays. They are more efficient UVA producers per unit of power consumption than fluorescent tubes.

LED

Ultraviolet light can be generated by some light-emitting diodes, but wavelengths shorter than 380 nm are uncommon, and the emission peaks are broad, so only the very lowest energy UV photons are emitted, within predominant not visible light.

Medical applications

A Wood's lamp is a diagnostic tool used in dermatology by which ultraviolet light is shone (at a wavelength of approximately 365 nanometers) onto the skin of the patient; a technician then observes any subsequent fluorescence. For example, porphyrins—associated with some skin diseases—will fluoresce pink. Though the technique for producing a source of ultraviolet light was devised by Robert Williams Wood in 1903 using "Wood's glass", it was in 1925 that the technique was used in dermatology by Margarot and Deveze for the detection of fungal infection of hair. It has many uses, both in distinguishing fluorescent conditions from other conditions and in locating the precise boundaries of the condition.

Fungal and bacterial infections

It is also helpful in diagnosing:

- Fungal infections. Some forms of tinea, such as Trichophyton tonsurans, do not fluoresce.

- Bacterial infections

- Corynebacterium minutissimum is coral red

- Pseudomonas is yellow-green

- Cutibacterium acnes, a bacterium involved in acne causation, exhibits an orange glow under a Wood's lamp.

Ethylene glycol poisoning

A Wood's lamp may be used to rapidly assess whether an individual is suffering from ethylene glycol poisoning as a consequence of antifreeze ingestion. Manufacturers of ethylene glycol-containing antifreezes commonly add fluorescein, which causes the patient's urine to fluoresce under Wood's lamp.

Other

Wood's lamp is useful in diagnosing conditions such as tuberous sclerosis and erythrasma (caused by Corynebacterium minutissimum, see above). Additionally, detection of porphyria cutanea tarda can sometimes be made when urine turns pink upon illumination with Wood's lamp. Wood's lamps have also been used to differentiate hypopigmentation from depigmentation such as with vitiligo. A vitiligo patient's skin will appear yellow-green or blue under the Wood's lamp. Its use in detecting melanoma has been reported.

See also

Bili light. A type of phototheraphy that uses blue light with a range of 420–470 nm, used to treat neonatal jaundice.

Safety

Although black lights produce light in the UV range, their spectrum is mostly confined to the longwave UVA region, that is, UV radiation nearest in wavelength to visible light, with low frequency and therefore relatively low energy. While low, there is still some power of a conventional black light in the UVB range. UVA is the safest of the three spectra of UV light, although high exposure to UVA has been linked to the development of skin cancer in humans. The relatively low energy of UVA light does not cause sunburn. UVA is capable of causing damage to collagen fibers, however, so it does have the potential to accelerate skin aging and cause wrinkles. UVA can also destroy vitamin A in the skin.

UVA light has been shown to cause DNA damage, but not directly, like UVB and UVC. Due to its longer wavelength, it is absorbed less and reaches deeper into skin layers, where it produces reactive chemical intermediates such as hydroxyl and oxygen radicals, which in turn can damage DNA and result in a risk of melanoma. The weak output of black lights, however, is not considered sufficient to cause DNA damage or cellular mutations in the way that direct summer sunlight can, although there are reports that overexposure to the type of UV radiation used for creating artificial suntans on sunbeds can cause DNA damage, photoaging (damage to the skin from prolonged exposure to sunlight), toughening of the skin, suppression of the immune system, cataract formation and skin cancer.

UV-A can have negative effects on eyes in both the short-term and long-term.

Uses

Ultraviolet radiation is invisible to the human eye, but illuminating certain materials with UV radiation causes the emission of visible light, causing these substances to glow with various colors. This is called fluorescence, and has many practical uses. Black lights are required to observe fluorescence, since other types of ultraviolet lamps emit visible light which drowns out the dim fluorescent glow.

Black light is commonly used to authenticate oil paintings, antiques and banknotes. Black lights can be used to differentiate real currency from counterfeit notes because, in many countries, legal banknotes have fluorescent symbols on them that only show under a black light. In addition, the paper used for printing money does not contain any of the brightening agents which cause commercially available papers to fluoresce under black light. Both of these features make illegal notes easier to detect and more difficult to successfully counterfeit. The same security features can be applied to identification cards such as passports or driver's licenses.

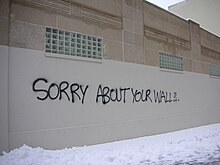

Other security applications include the use of pens containing a fluorescent ink, generally with a soft tip, that can be used to "invisibly" mark items. If the objects that are so marked are subsequently stolen, a black light can be used to search for these security markings. At some amusement parks, nightclubs and at other, day-long (or night-long) events, a fluorescent mark is rubber stamped onto the wrist of a guest who can then exercise the option of leaving and being able to return again without paying another admission fee.

In medicine, the Wood's lamp is used to check for the characteristic fluorescence of certain dermatophytic fungi such as species of Microsporum which emit a yellow glow, or Corynebacterium which have a red to orange color when viewed under a Wood's lamp. Such light is also used to detect the presence and extent of disorders that cause a loss of pigmentation, such as vitiligo. It can also be used to diagnose other fungal infections such as ringworm, Microsporum canis, tinea versicolor; bacterial infections such erythrasma; other skin conditions including acne, scabies, alopecia, porphyria; as well as corneal scratches, foreign bodies in the eye, and blocked tear ducts.

Fluorescent materials are also very widely used in numerous applications in molecular biology, often as "tags" which bind themselves to a substance of interest (for example, DNA), so allowing their visualization. Black light can also be used to see animal excreta such as urine and vomit that is not always visible to the naked eye.

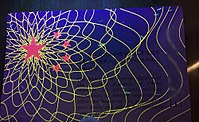

Black light is used extensively in non-destructive testing. Fluorescing fluids are applied to metal structures and illuminated with a black light which allows cracks and other weaknesses in the material to be easily detected. It is also used to illuminate pictures painted with fluorescent colors, particularly on black velvet, which intensifies the illusion of self-illumination. The use of such materials, often in the form of tiles viewed in a sensory room under UV light, is common in the United Kingdom for the education of students with profound and multiple learning difficulties. Such fluorescence from certain textile fibers, especially those bearing optical brightener residues, can also be used for recreational effect, as seen, for example, in the opening credits of the James Bond film A View to a Kill. Black light puppetry is also performed in a black light theater.

One of the innovations for night and all-weather flying used by the US, UK, Japan and Germany during World War II was the use of UV interior lighting to illuminate the instrument panel, giving a safer alternative to the radium-painted instrument faces and pointers, and an intensity that could be varied easily and without visible illumination that would give away an aircraft's position. This went so far as to include the printing of charts that were marked in UV-fluorescent inks, and the provision of UV-visible pencils and slide rules such as the E6B.

Thousands of moth and insect collectors all over the world use various types of black lights to attract moth and insect specimens for photography and collecting. It is one of the preferred light sources for attracting insects and moths at night.

It may also be used to test for LSD, which fluoresces under black light while common substitutes such as 25I-NBOMe do not.

In addition, if a leak is suspected in a refrigerator or an air conditioning system, a UV tracer dye can be injected into the system along with the compressor lubricant oil and refrigerant mixture. The system is then run in order to circulate the dye across the piping and components and then the system is examined with a blacklight lamp. Any evidence of fluorescent dye then pinpoints the leaking part which needs replacement.

The security thread of a US $20 bill glows green under black light as a safeguard against counterfeiting.

Anti-counterfeiting design of a Chinese passport glows under black light.

Scorpion fluorescing under ultraviolet from a black light

Decorative use of black light in a nightclub