A trebuchet (French: trébuchet) is a type of catapult that uses a long arm to throw a projectile. It was a common powerful siege engine until the advent of gunpowder. The design of a trebuchet allows it to launch projectiles of greater weights further distances than that of a traditional catapult.

There are two main types of trebuchets. The first is the traction trebuchet, or mangonel, which uses manpower to swing the arm. It first appeared in China in the 4th century BC. Carried westward by the Avars, the technology was adopted by the Byzantines in the late 6th century AD and by their neighbors in the following centuries.

The later, and often larger and more powerful, counterweight trebuchet, also known as the counterpoise trebuchet, uses a counterweight to swing the arm. It appeared in both Christian and Muslim lands around the Mediterranean in the 12th century, and was carried back to China by the Mongols in the 13th century.

Etymology and terminology

It is uncertain what the origin of "trebuchet" is. D.J. Cathcart King suggests that it is derived from "trebucher, to rock or tilt." The numerous forms of the word that appeared during the 13th century, including trabocco, tribok, tribuclietta, and trubechetum, have made it impossible to identify the source with any certainty. In Arabic the counterweight trebuchet was called manjaniq maghribi or majaniq ifranji. In China it was called the huihui pao (Muslim trebuchet).

The earliest appearance of the term "trebuchet" dates to the late 12th century. The word trabuchellus appeared alongside manganum and prederia in a document in Vicenza on 6 April 1189. Trabucha is found a decade later with predariae at the siege of Castelnuovo Bocca d'Adda in an account by Iohannes Codagnellus. However it is unclear if these referred to counterweight trebuchets. Codagnellus did not specify a specific type of engine with the term and even implied that they were "fairly light in subsequent references." Only in the late 1210s do variations of "trebuchet" in sources, described as increasingly powerful machines or utilizing different components, identify more closely with the counterweight trebuchet.

Traction trebuchet and counterweight trebuchet are modern terms (retronyms), not used by contemporary users of the weapons. The term traction trebuchet was created mainly to distinguish this type of weapon from the onager, a torsion powered catapult which is often conflated in contemporary sources with the mangonel, which was used as a generic term for any medieval stone throwing artillery. Both the traction and counterweight trebuchets have been called mangonel at one point or another. Confusion between the onager, mangonel, trebuchet and other catapult types in contemporary terminology has led some historians today to use the more precise traction trebuchet instead, with counterweight trebuchet used to distinguish what was before called simply a trebuchet. Some modern historians use mangonel to mean exclusively traction trebuchets, some call traction trebuchets traction mangonels, and counterweight trebuchets counterweight mangonels.

Basic design

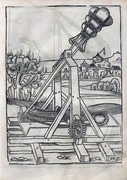

The trebuchet is a compound machine that makes use of the mechanical advantage of a lever to throw a projectile. They are typically large constructions, with the length of the beam as much as 15 meters (50 ft), with some purported to be even larger. They are made primarily of wood, usually reinforced with metal, leather, rope, and other materials. They are usually immobile and must be assembled on-site, possibly making use of local lumber with only key parts brought with the army to the site of the siege or battle.

A trebuchet consists primarily of a long beam attached by an axle suspended high above the ground by a stout frame and base, such that the beam can rotate vertically through a wide arc (typically over 180°). A sling is attached to one end of the beam to hold the projectile. The projectile is thrown when the beam is quickly rotated by applying force to the opposite end of the beam. The mechanical advantage is primarily obtained by having the projectile section of the beam much longer than the opposite section where the force is applied – usually four to six times longer.

The difference between counterweight and traction trebuchets is what force they use. Counterweight trebuchets use gravity; potential energy is stored by slowly raising an extremely heavy box (typically filled with stones, sand, or lead) attached to the shorter end of the beam (typically on a hinged connection), and releasing it on command. Traction trebuchets use human power; on command, men pull ropes attached to the shorter end of the trebuchet beam. The difficulties of coordinating the pull of many men together repeatedly and predictably makes counterweight trebuchets preferable for the larger machines, though they are more complicated to engineer. Further increasing their complexity is that either winches or treadwheels, aided by block and tackle, are typically required to raise the more massive counterweights. So while counterweight trebuchets require significantly fewer men to operate than traction trebuchets, they require significantly more time to reload. In a long siege, reload time may not be a critical concern.

When the trebuchet is operated, the force causes rotational acceleration of the beam around the axle (the fulcrum of the lever). These factors multiply the acceleration transmitted to the throwing portion of the beam and its attached sling. The sling starts rotating with the beam, but rotates farther (typically about 360°) and therefore faster, transmitting this increased speed to the projectile. The length of the sling increases the mechanical advantage, and also changes the trajectory so that, at the time of release from the sling, the projectile is traveling in the desired speed and angle to give it the range to hit the target. Adjusting the sling's release point is the primary means of fine-tuning the range, as the rest of the trebuchet's actions are difficult to adjust after construction.

The rotation speed of the throwing beam increases smoothly, starting slow but building up quickly. After the projectile is released, the arm continues to rotate, allowed to smoothly slow down on its own accord and come to rest at the end of the rotation. This is unlike the violent sudden stop inherent in the action of other catapult designs such as the onager, which must absorb most of the launching energy into their own frame, and must be heavily built and reinforced as a result. This key difference makes the trebuchet much more durable, allowing for larger and more powerful machines.

A trebuchet projectile can be almost anything, even debris, rotting carcasses, or incendiaries, but is typically a large stone. Dense stone, or even metal, specially worked to be round and smooth, gives the best range and predictability. When attempting to breach enemy walls, it is important to use materials that will not shatter on impact; projectiles were sometimes brought from distant quarries to get the desired properties.

History

Traction trebuchet

The traction trebuchet, also referred to as a mangonel in some sources, is thought to have originated in ancient China. Torsion-based siege weapons such as the ballista and onager are not known to have been used in China.

The first recorded use of traction trebuchets was in ancient China. They were probably used by the Mohists as early as 4th century BC; descriptions can be found in the Mojing (compiled in the 4th century BC). According to the Mojing, the traction trebuchet was 17 feet high with four feet buried below ground, the fulcrum attached was constructed from the wheels of a cart, the throwing arm was 30 to 35 feet long with three quarters above the pivot and a quarter below to which the ropes are attached, and the sling two feet and eight inches long. The range given for projectiles are 300, 180, and 120 feet. They were used as defensive weapons stationed on walls and sometimes hurled hollowed out logs filled with burning charcoal to destroy enemy siege works. By the 1st century AD, commentators were interpreting other passages in texts such as the Zuo zhuan and Classic of Poetry as references to the traction trebuchet: "the guai is 'a great arm of wood on which a stone is laid, and this by means of a device is shot off and so strikes down the enemy.'" The Records of the Grand Historian say that "The flying stones weigh 12 catties and by devices are shot off 300 paces." Traction trebuchets went into decline during the Han dynasty due to long periods of peace but became a common siege weapon again during the Three Kingdoms period. They were commonly called stone-throwing machines, thunder carriages, and stone carriages in the following centuries. They were used as ship mounted weapons by 573 for attacking enemy fortifications. It seems that during the early 7th century, improvements were made on traction trebuchets, although it is not explicitly stated what. According to a stele in Barkul celebrating Tang Taizong's conquest of what is now Ejin Banner, the engineer Jiang Xingben made great advancements on trebuchets that were unknown in ancient times. Jiang Xingben participated in the construction of siege engines for Taizong's campaigns against the Western Regions. In 617 Li Mi (Sui dynasty) constructed 300 trebuchets for his assault on Luoyang, in 621 Li Shimin did the same at Luoyang, and onward into the Song dynasty when in 1161, trebuchets operated by Song dynasty soldiers fired bombs of lime and sulphur against the ships of the Jin dynasty navy during the Battle of Caishi.

For the trebuchet they use large baulks of wood to make the framework, fixing it on four wheels below. From this there rise up two posts having between them a horizontal bar which carries a single arm so that the top of the machine is like a swape. The arm is arranged as to height, length and size, according to the city [which it is proposed to attack or defend]. At the end of the arm there is a sling which holds the stone or stones, of weight and number depending on the stoutness of the arm. Men [suddenly] pull [ropes attached to the other] end, and so shoot it forth. The carriage framework can be pushed and turned around at will. Alternatively the ends [of the beams of the framework] can be buried in the ground and so used. [But whether you use] the 'Whirlwind' type or the 'Four-footed' type depends upon the circumstances.

— Li Quan

The traction trebuchet was carried westward by the Avars and appeared next in the eastern Mediterranean by the late 6th century AD, where it replaced torsion powered siege engines such as the ballista and onager. The rapid displacement of torsion siege engines was probably due to a combination of reasons. The traction trebuchet is simpler in design, has a faster rate of fire, increased accuracy, and comparable range and power. It was probably also safer than the twisted cords of torsion weapons, "whose bundles of taut sinews stored up huge amounts of energy even in resting state and were prone to catastrophic failure when in use." At the same time, the late Roman Empire seems to have fielded "considerably less artillery than its forebears, organised now in separate units, so the weaponry that came into the hands of successor states might have been limited in quantity." Evidence from Gaul and Germania suggests there was substantial loss of skills and techniques in artillery further west.

According to the Miracles of Saint Demetrius, probably written around 620 by John, Archbishop of Thessaloniki, the Avaro-Slavs attacked Thessaloniki in 586 with traction trebuchets. The bombardment lasted for hours, but the operators were inaccurate and most of the shots missed their target. When one stone did reach their target, it "demolished the top of the rampart down to the walkway." The Byzantines adopted the traction trebuchet possibly as early as 587, the Persians in the early 7th century, and the Arabs in the second half of the 7th century. Like the Chinese, by 653, the Arabs also had ship mounted traction trebuchet. The Franks and Saxons adopted the weapon in the 8th century. The Life of Louis the Pious contains the earliest western European reference to mangonels (traction trebuchets) in its account of the siege of Tortosa (808–809). In 1173, the Republic of Pisa tried to capture an island castle with traction trebuchet on galleys. Traction trebuchets were also used in India.

The catapult, the account of which has been translated from the Greek several times, was quadrangular, with a wide base but narrowing towards the top, using large iron rollers to which were fixed timber beams "similar to the beams of big houses", having at the back a sling, and at the front thick cables, enabling the arm to be raised and lowered, and which threw "enormous blocks into the air with a terrifying noise".

— Peter Purton

The traction trebuchet was most efficient as an anti-personnel weapon, used in a supportive position alongside archers and slingers. Most accounts of traction trebuchets describe them as light artillery weapons while actual penetration of defenses was the result of mining or siege towers. At the Siege of Kamacha in 766, Byzantine defenders used wooden cover to protect themselves from the enemy artillery while inflicting casualties with their own stone throwers. Michael the Syrian noted that at the siege of Balis in 823 it was the defenders that suffered from bombardment rather than the fortifications. At the siege of Kaysum, Abdallah ibn Tahir al-Khurasani used artillery to damage houses in the town. The Sack of Amorium in 838 saw the use of traction trebuchets to drive away defenders and destroy wooden defenses. At the siege of Marand in 848, traction trebuchets were used, "reportedly killing 100 and wounding 400 on each side during the eight-month siege." During the siege of Baghdad in 865, defensive artillery were responsible for repelling an attack on the city gate while traction trebuchets on boats claimed a hundred of the defenders' lives.

Some exceptionally large and powerful traction trebuchets have been described during the 11th century or later. At the Siege of Manzikert (1054), the Seljuks' initial siege artillery was countered by the defenders' own, which shot stones at the besieging machine. In response, the Seljuks constructed another one requiring 400 men to pull and threw stones weighing 20 kg. A breach was created on the first shot but the machine was burnt down by the defenders. According to Matthew of Edessa, this machine weighed 3,400 kg and caused a number of casualties to the city's defenders. Ibn al-Adim describes a traction trebuchet capable of throwing a man in 1089. At the siege of Haizhou in 1161, a traction trebuchet was reported to have had a range of 200 paces (over 400 meters).

West of China, the traction trebuchet remained the primary siege engine until the 12th century when it was replaced by the counterweight trebuchet. In China the traction trebuchet was the primary siege engine until the counterweight trebuchet was introduced during the Mongol conquest of the Song dynasty in the 13th century.

Five whirlwind trebuchets from the Wujing Zongyao

Crouching tiger trebuchet from the Wujing Zongyao

Sìjiǎo "Four Footed" traction trebuchet from the Wujing Zongyao

Traction trebuchet on a Song Dynasty warship from the Wujing Zongyao

Muslim traction trebuchet, 1285

Counterweight trebuchet

The counterweight trebuchet has been described as the "most powerful weapon of the Middle Ages".

The earliest known description and illustration of a counterweight trebuchet comes from a commentary on the conquests of Saladin by Mardi ibn Ali al-Tarsusi in 1187. However cases for the existence of both European and Muslim counterweight trebuchets prior to 1187 have been made. In 1090, Khalaf ibn Mula'ib threw out a man from the citadel in Salamiya with a machine and in the early 12th century, Muslim siege engines were able to breach crusader fortifications. David Nicolle argues that these events could have only been possible with the use of counterweight trebuchets.

Paul E. Chevedden argues that counterweight trebuchets appeared prior to 1187 in Europe based on what might have been counterweight trebuchets in earlier sources. The 12th-century Byzantine historian Niketas Choniates may have been referring to a counterweight trebuchet when he described one equipped with a windlass, which is only useful to counterweight machines, at the siege of Zevgminon in 1165. At the siege of Nicaea in 1097 the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos reportedly invented new pieces of heavy artillery which deviated from the conventional design and made a deep impression on everyone. Possible references to counterweight trebuchets also appear for the second siege of Tyre in 1124, where the crusaders reportedly made use of "great trebuchets". Chevedden argues that given the references to new and better trebuchets that by the 1120–30s, the counterweight trebuchet was being used in a variety of places by different peoples such as the crusader states, the Normans of Sicily and the Seljuks.

The earliest solid reference to a "trebuchet" in European sources dates to the siege of Castelnuovo Bocca d'Adda in 1199. However it is unclear if this referred to counterweight trebuchets since the author did not specify what engine was used and described the machine as fairly light. They may have been used in Germany from around 1205. Only in the late 1210s do references to "trebuchet", describing more powerful engines and different components, more closely align with the features of a counterweight trebuchet. Some of these more powerful engines may have just been traction trebuchets, as one was described being pulled by ten thousand. At the Siege of Toulouse (1217–1218), trabuquets were mentioned to have been deployed, but the siege engine depicted at the tomb of Simon de Montfort, who was killed by artillery at the siege, is a traction trebuchet. Though soon after, clear evidence of counterweight machines appeared. According to the Song of the Albigensian Crusade, the defenders "ran to the ropes and wound the trebuchets," and to shoot the machine, they "then released their ropes." They were used in England at least by 1217 and in Iberia shortly after 1218. By the 1230s the counterweight trebuchet was a common item in siege warfare. Despite the lack of clearly definable terms in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, it is likely that both Muslims and Europeans already had working knowledge of the counterweight trebuchet beforehand. By the time of the Third Crusade (1189–1192), both sides seemed well acquainted with the enemy's siege weapons, which "appear to have been remarkably similar."

Counterweight trebuchets do not appear with certainty in Chinese historical records until about 1268. Prior to 1268, the counterweight trebuchet may have been used in 1232 by the Jurchen Jin commander Qiang Shen. Qiang invented a device called the "Arresting Trebuchet" which only needed a few men to work it, and could hurl great stones more than a hundred paces, further than even the strongest traction trebuchet. However no other details on the machine are given. Qiang died the following year and no further references to the Arresting Trebuchet appear. The earliest definite mention of the counterweight trebuchet in China was in 1268, when the Mongols laid siege to Fancheng and Xiangyang. After failing to take the twin cities of Fancheng and Xiangyang for several years, collectively known as the siege of Fancheng and Xiangyang, the Mongol army brought in two Persian engineers to build hinged counterweight trebuchets. Known as the Huihui trebuchet (回回砲, where "huihui" is a loose slang referring to any Muslims), or Xiangyang trebuchet (襄陽砲) because they were first encountered in that battle. Ismail and Al-aud-Din travelled to South China from Iraq and built trebuchets for the siege. Chinese and Muslim engineers operated artillery and siege engines for the Mongol armies. By 1283, counterweight trebuchets were also used in Southeast Asia by the Chams against the Yuan dynasty.[63]

The design of the Muslim trebuchets came originally from the Muslim countries, and they were more powerful than ordinary trebuchets. In the case of the largest ones, the wooden framework stood above a hole in the ground. The projectiles were several feet in diameter, and when they fell to the earth they made a hole three or four feet deep. when [the artillerists] wanted to hurl them to a great range, they added weight [to the counterpoise] and set it further back [on the arm] when they needed only a shorter distance, they set it forward, nearer [the fulcrum].

— Zheng Sixiao

While some historians have described the counterweight trebuchet as a type of medieval super weapon, other historians have urged caution in overemphasizing its destructive capability. On the side of the counterweight engine as a medieval military revolution, historians such as Sydney Toy, Paul Chevedden, and Hugh Kennedy consider its power to have caused significant changes in medieval warfare. This line of thought suggests that rams were abandoned due to the effectiveness of the counterweight trebuchet, which was capable of reducing "any fortress to rubble." Accordingly, traditional fortifications became obsolete and had to be improved with new architectural structures to support defensive counterweight trebuchets. On the side of caution, historians such as John France, Christopher Marshall, and Michael Fulton emphasize the still considerable difficulty of reducing fortifications with siege artillery. Examples of the failure of siege artillery include the lack of evidence that artillery ever threatened the defenses of Kerak Castle between 1170 and 1188. Marshall maintains that "the methods of attack and defence remained largely the same through the thirteenth century as they had been during the twelfth." Reservations on the counterweight trebuchet's destructive capability were expressed by Viollet-le-Duc, who "asserted that even counterweight-powered artillery could do little more than destroy crenellations, clear defenders from parapets and target the machines of the besieged."

In spite of the evidence regarding increasingly powerful counterweight trebuchets during the 13th century, "it remains an important consideration that not one of these appears to have effected a breach that directly led to the fall of a stronghold." In 1220, Al-Mu'azzam Isa laid siege to Atlit with a trabuculus, three petrariae, and four mangonelli but could not penetrate past the outer wall, which was soft but thick. As late as the Siege of Acre (1291), where the Mamluk Sultanate fielded 72 or 92 trebuchets, including 14 or 15 counterweight trebuchets and the remaining traction types, they were never able to fulfill a breaching role. The Mamluks entered the city by sapping the northeast corner of the outer wall. Though stone projectiles of substantial size (~66kg) have been found at Acre, located near the site of the siege and likely used by the Mamluks, surviving walls of a 13th century Montmusard tower are no more than one meter thick. There is no indication that the thickness of fortress walls increased exponentially rather than a modest increase of 0.5-1m between the 12th and 13th centuries. The Templar of Tyre described the faster firing traction trebuchets as more dangerous to the defenders than the counterweight ones. The Song dynasty described countermeasures against counterweight trebuchets that prevented them from damaging towers and houses: "an extraordinary method was invented of neutralising the effects of the enemy's trebuchets. Ropes of rice straw four inches thick and thirty-four feet long were joined together twenty at a time, draped on to the buildings from top to bottom, and covered with [wet] clay. Then neither the incendiary arrows, nor bombs [huo pao] from trebuchets, nor even stones of a hundred jun caused any damage to the towers and houses."

The counterweight trebuchet did not completely replace the traction trebuchet. Despite its greater range, counterweight trebuchets had to be constructed close to the site of the siege unlike traction trebuchets, which were smaller, lighter, cheaper, and easier to take apart and put back together again where necessary. The superiority of the counterweight trebuchet was not clear cut. Of this, the Hongwu Emperor stated in 1388: "The old type of trebuchet was really more convenient. If you have a hundred of those machines, then when you are ready to march, each wooden pole can be carried by only four men. Then when you reach your destination, you encircle the city, set them up, and start shooting!" The traction trebuchet continued to serve as an anti-personnel weapon. The Norwegian text of 1240, Speculum regale, explicitly states this division of functions. Traction trebuchets were to be used for hitting people in undefended areas. At the Siege of Acre (1291), both traction and counterweight trebuchets were used. The traction trebuchets provided cover fire while the counterweight trebuchets destroyed the city's fortifications.

Rather than replace traction trebuchets, counterweight trebuchets supplemented them in a different role. Their slower shooting rate and greater mass made them more difficult to reposition, or even yaw, leaving few incentives to employ a small counterweight engine rather than a comparable traction type. Although less accurate, traction trebuchets might be expected to achieve the same result, albeit with more shots, in a similar amount of time. Accordingly, it was only profitable to employ counterweight trebuchets if they were capable of harnessing noticeably more energy, allowing them to throw significantly larger stones or similarly sized stones greater distances.

— Michael S. Fulton

There is some evidence that the counterweight trebuchet could be transported, as shown in two 17th- and 18th-century Chinese illustrations, which are also the only Chinese depictions of counterweight trebuchets on land. According to Liang Jieming, the "illustration shows... its throwing arm disassembled, its counterweight locked with supporting braces, and prepped for transport and not in battle deployment." However according to Joseph Needham, the large tank in the middle was the counterweight, while the bulb at the end of the arm was for adjusting between fixed and swinging counterweights. Both Liang and Needham note that the illustrations are poorly drawn and confusing, leading to mislabeling.

The counterweight and traction trebuchets were phased out around the mid-15th century in favor of gunpowder weapons.

Conquest of Baghdad (1258), from the Jami' al-tawarikh, 14th century

A Chinese counterweight trebuchet packed for transport, from the Wubei Zhi

Decline of military use

With the introduction of gunpowder, the trebuchet began to lose its place as the siege engine of choice to the cannon. Trebuchets were still used both at the siege of Burgos (1475–1476) and siege of Rhodes (1480). One of the last recorded military uses was by Hernán Cortés, at the 1521 siege of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlán. Accounts of the attack note that its use was motivated by the limited supply of gunpowder. The attempt was reportedly unsuccessful: the first projectile landed on the trebuchet itself, destroying it.

In China, the last time trebuchets were seriously considered for military purposes was in 1480. Not much is heard of them afterwards.

Other trebuchets

Hand-trebuchet

The hand-trebuchet (Greek: cheiromangana) was a staff sling mounted on a pole using a lever mechanism to propel projectiles. Basically a one-man traction trebuchet, it was used by emperor Nikephoros II Phokas around 965 to disrupt enemy formations in the open field. It was also mentioned in the Taktika of general Nikephoros Ouranos (c. 1000), and listed in De obsidione toleranda (author anonymous) as a form of artillery.

In China, the hand-trebuchet (shoupao) was invented by Liu Yongxi and presented to the emperor in 1002. It was a pole with a pin at its upper end that acted as a fulcrum for the arm. The pole was used as a shot for fixing in the ground and the user could then throw missiles at the enemy from a static position.

Hybrid trebuchet

According to Paul E. Chevedden, a hybrid trebuchet existed that used both counterweight and human propulsion. However no illustrations or descriptions of the device exist from the time when they were supposed to have been used. The entire argument for the existence of hybrid trebuchets rests on accounts of increasingly more effective siege weapons. Peter Purton suggests that this was simply because the machines became larger. The earliest depiction of a hybrid trebuchet is dated to 1462, when trebuchets had already become obsolete due to cannons.

Couillard

The couillard is a smaller version of a counterweight trebuchet with a single frame instead of the usual double "A" frames. The counterweight is split into two halves to avoid hitting the center frame.

Comparison of different artillery weapons

Roman torsion engines

| Weapon | Projectile weight (kg) | Range (m) |

|---|---|---|

| Ballista (stone thrower) | 26.2 | 366 |

| Ballista (early bolt thrower) | ? | 300 |

| Ballista (late dart thrower) | ? | 1,100 |

| Ballista (reconstruction) | 0.6 stone/0.4 lead | 180/300 |

| Ballista (reconstruction) | 26 | 82 |

| Onager (reconstruction) | ? (very light) | 130–275 |

| Onager (Vitruvius reconstruction) | 26 | 90 |

Chinese trebuchets

| Weapon | Crew | Projectile weight (kg) | Range (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whirlwind trebuchet | 50 (rotating) | 1.8 | 78 |

| Crouching tiger trebuchet | 70 (rotating) | 7.25 | 78 |

| Four footed (one arm) trebuchet | 40 (rotating) | 1.1 | 78 |

| Four footed (two arm) trebuchet | 100 (rotating) | 11.3 | 120 |

| Four footed (five arm) trebuchet | 157 (rotating) | 44.5 | 78 |

| Four footed (seven arm) trebuchet | 250 (rotating) | 56.7 | 78 |

| Counterweight trebuchet | 10 | ~86 | 200–275 |

Siege crossbows

| Weapon | Crew | Draw weight (kg) | Range (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mounted multi-bolt crossbow | 460 | ||

| Mounted single-bow crossbow | 4–7 | 250–500 | |

| Mounted double-bow crossbow | 10 | 350–520 | |

| Mounted triple-bow crossbow | 20–100 | 950–1,200 | 460–1,060 |

| European siege crossbow (15th c.) | 545 | 365–420 |

Reconstructed traction trebuchets

| Pullers | Projectile weight (kg) | Shots per minute | Max range (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6-9 | 5-15 | ~100 | |

| 14 | 3.1 | 145 | |

| 20 | 1.9 | 4–6 | 137 |

Reconstructed counterweight trebuchets

| Counterweight (kg) | Projectile weight (kg) | Range (m) |

|---|---|---|

| 2,000 | 12–15 | 120–168 |

| 4,000 | 8–12 | 445 |

| 100 | 185 | |

| 6,000 | 55 | 320 |

| 100 | 200 |

Modern use

Recreation and education

Most trebuchet use in recent centuries has been for recreational or educational, rather than military purposes. New machines have been constructed and old ones restored by living history enthusiasts, for historical re-enactments, and use in other historical celebrations. As their construction is substantially simpler than modern weapons, trebuchets also serve as the object of engineering challenges.

The trebuchet's technical constructions were lost at the beginning of the 16th century. In 1984, the French engineer Renaud Beffeyte made the first modern reconstruction of a trebuchet, based on documents from 1324.

The largest currently-functioning trebuchet in the world is the 22-tonne machine at Warwick Castle, England, constructed in 2005. Based on historical designs, it stands 18 metres (59 ft) tall and throws missiles typically 36 kg (80 lbs) up to 300 metres (980 ft). The trebuchet gained significant interest from numerous news sources when in 2015 a burning missile fired from the siege engine struck and damaged a Victorian-era boathouse situated at the River Avon close by, inadvertently demonstrating the weapon's power. It is built on the design of a similar trebuchet at Middelaldercentret in Denmark. In 1989, Middelaldercentret became the first place in the modern era to have a working trebuchet.

Trebuchets compete in one of the classifications of machines used to hurl pumpkins at the annual pumpkin chucking contest held in Sussex County, Delaware, U.S. The record-holder in that contest for trebuchets is the Yankee Siege II from New Hampshire, which at the 2013 WCPC Championship tossed a pumpkin 2835.8 ft (864.35 metres). The 51-foot-tall (16 m), 55,000-pound (25,000 kg) trebuchet flings the standard 8–10-pound (3.6–4.5 kg) pumpkins, specified for all entries in the WCPC competition.

A large trebuchet was tested in late 2017 in Belfast as part of the set for the television series Game of Thrones.

A large trebuchet based on Edward I's "Warwolf" was constructed for a scene in David Mackenzie's movie Outlaw King (2018) about Robert the Bruce, King of Scots. During the film, it hurls an incendiary projectile at Stirling Castle. It recreates the true story that it took some three months to build, and Edward I "Longshanks" would not let his enemy surrender until he could use it.

Developments

Although rarely used as a weapon today, trebuchets maintain the interest of professional and hobbyist engineers. One modern technological development, especially for the competitive pumpkin-hurling events, is the "floating arms" design. Instead of using the traditional axle fixed to a frame, these devices are mounted on wheels that roll on a track parallel to the ground, with a counterweight that falls directly downward upon release, allowing for greater efficiency by increasing the proportion of energy transferred to the projectile. A more radical design; Jonathan, Orion, and Emmerson Stapleton's "walking arm", described as "...a stick falling over with a huge counterweight on top of the stick..." debuted in 2016 and in 2018 won both the Grand Champion Best Design and Middleweight Open Division of the 10th annual Vermont Pumpkin Chuckin Festival. Another recent development is the "flywheel trebuchet," in which a flywheel is spun into rapid rotation to build up momentum before release.

In 2021, an individual named David Eade designed a trebuchet reaching supersonic speed. He demonstrated the device on YouTube and published his simulation software on GitHub.

Uses in activism and insurgency

In 2013, during the Syrian civil war, rebels were filmed using a trebuchet in the Battle of Aleppo. The trebuchet was used to project explosives at government troops.

In 2014, during the Hrushevskoho street riots in Ukraine, rioters used an improvised trebuchet to throw bricks and molotov cocktails at the Berkut.

Gallery

Modern traction trebuchet, Inner Mongolia Museum

Trebuchet at Middelaldercentret, Denmark

Counterweight trebuchet at Château des Baux, France

Trebuchet constructed on the design of the "Warwolf"