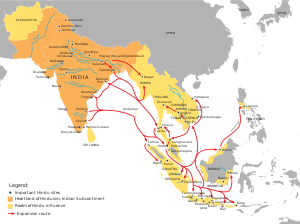

Greater India, or the Indian cultural sphere, is an area composed of many countries and regions in South and Southeast Asia that were historically influenced by Indian culture, which itself formed from the various distinct indigenous cultures of these regions. Specifically Southeast Asian influence on early India had lasting impacts on the formation of Hinduism and Indian mythology. Hinduism itself formed from various distinct folk religions, which merged during the Vedic period and following periods. The term Greater India as a reference to the Indian cultural sphere was popularised by a network of Bengali scholars in the 1920s. It is an umbrella term encompassing the Indian subcontinent, and surrounding countries which are culturally linked through a diverse cultural cline. These countries have been transformed to varying degrees by the acceptance and induction of cultural and institutional elements from each other. Since around 500 BCE, Asia's expanding land and maritime trade had resulted in prolonged socio-economic and cultural stimulation and diffusion of Hindu and Buddhist beliefs into the region's cosmology, in particular in Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka. In Central Asia, transmission of ideas were predominantly of a religious nature. The spread of Islam significantly altered the course of the history of Greater India.[7]

By the early centuries of the common era, most of the principalities of Southeast Asia had effectively absorbed defining aspects of Hindu culture, religion and administration. The notion of divine god-kingship was introduced by the concept of Harihara, Sanskrit and other Indian epigraphic systems were declared official, like those of the south Indian Pallava dynasty and Chalukya dynasty. These Indianized Kingdoms, a term coined by George Cœdès in his work Histoire ancienne des états hindouisés d'Extrême-Orient, were characterized by surprising resilience, political integrity and administrative stability.

To the north, Indian religious ideas were assimilated into the cosmology of Himalayan peoples, most profoundly in Tibet and Bhutan and merged with indigenous traditions. Buddhist monasticism extended into Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and other parts of Central Asia, and Buddhist texts and ideas were readily accepted in China and Japan in the east. To the west, Indian culture converged with Greater Persia via the Hindukush and the Pamir Mountains.

Evolution of the concept

The concept of the Three Indias was in common circulation in pre-industrial Europe. Greater India was the southern part of South Asia, Lesser India was the northern part of South Asia, and Middle India was the region near the Middle East. The Portuguese form (Portuguese: India Maior) was used at least since the mid-15th century. The term, which seems to have been used with variable precision, sometimes meant only the Indian subcontinent; Europeans used a variety of terms related to South Asia to designate the South Asian peninsula, including High India, Greater India, Exterior India and India aquosa.

However, in some accounts of European nautical voyages, Greater India (or India Major) extended from the Malabar Coast (present-day Kerala) to India extra Gangem (lit. "India, beyond the Ganges," but usually the East Indies, i.e. present-day Malay Archipelago) and India Minor, from Malabar to Sind. Farther India was sometimes used to cover all of modern Southeast Asia. Until the fourteenth century, India could also mean areas along the Red Sea, including Somalia, South Arabia, and Ethiopia (e.g., Diodorus of Sicily of the first century BC says that "the Nile rises in India" and Marco Polo of the fourteenth century says that "Lesser India ... contains ... Abash [Abyssinia]").

In late 19th-century geography, Greater India referred to a region that included: "(a) Himalaya, (b) Punjab, (c) Hindustan, (d) Burma, (e) Indo-China, (f) Sunda Islands, (g) Borneo, (h) Celebes, and (i) Philippines."[24] German atlases distinguished Vorder-Indien (Anterior India) as the South Asian peninsula and Hinter-Indien as Southeast Asia.

Greater India, or Greater India Basin also signifies "the Indian Plate plus a postulated northern extension", the product of the Indian–Asia collision. Although its usage in geology pre-dates Plate tectonic theory, the term has seen increased usage since the 1970s. It is unknown when and where the India–Asia (Indian and Eurasian Plate) convergence occurred, at or before 52 Million years ago. The plates have converged up to 3,600 km (2,200 mi) ± 35 km (22 mi). The upper crustal shortening is documented from geological record of Asia and the Himalaya as up to approximately 2,350 km (1,460 mi) less.

Indianization of South East Asia

Indianization is different from direct colonialism in that these Indianized lands were not inhabited by organizations or state elements from the Indian subcontinent, with exceptions such as the Chola invasions of medieval times. Instead, Indian cultural influence from trade routes and language use slowly permeated through Southeast Asia, making the traditions a part of the region. The interactions between India and Southeast Asia were marked by waves of influence and dominance. At some points, the Indian culture solely found its way into the region, and at other points, the influence was used to take over. A reason for the fast acceptance of Indian culture in Southeast Asia was because Indian culture already had striking similarities to indigenous cultures of Southeast Asia, which can be explained by earlier Southeast Asian (specifically Austroasiatic, such as early Munda and Mon Khmer groups) and Himalayan (Tibetic) cultural and linguistic influence on local Indian peoples. Several scholars, such as Professor Przyluski, Jules Bloch, and Lévi, among others, concluded that there is a significant cultural, linguistic, and political Mon-Khmer (Austroasiatic) influence on early India. Genetic evidence further found noteworthy East Asian-related ancestry among various Indian ethnic groups. The East Asian-related ancestry component is forming the major ancestry among specific populations in the Himalayan foothills and Northeast India, and is generally distributed throughout the Indian subcontinent, peaking among Austroasiatic-speaking groups, as well as among Sinhalese and Bengalis.

The concept of the Indianized kingdoms, a term coined by George Coedès, describes Southeast Asian principalities that flourished from the early common era as a result of centuries of socio-economic interaction having incorporated central aspects of Indian institutions, religion, statecraft, administration, culture, epigraphy, literature and architecture.

Iron Age trade expansion caused regional geostrategic remodeling. Southeast Asia was now situated in the central area of convergence of the Indian and the East Asian maritime trade routes, the basis for economic and cultural growth. The earliest Hindu kingdoms emerged in Sumatra and Java, followed by mainland polities such as Funan and Champa. Adoption of Indian civilization elements and individual adaptation stimulated the emergence of centralized states and the development of highly organized societies. Ambitious local leaders realized the benefits of Hinduism and Indian methods of administration, culture, literature, etc. Rule in accord with universal moral principles, represented in the concept of the devaraja, was more appealing than the Chinese concept of intermediaries.

Theories of Indianization

As conclusive evidence is missing, numerous Indianization theories of Southeast Asia have emerged since the early 20th century. The central question usually revolves around the main propagator of Indian institutional and cultural ideas in Southeast Asia.

One theory of the spread of Indianization that focuses on the caste of Vaishya traders and their role for spreading Indian culture and language into Southeast Asia through trade. There were many trade incentives that brought Vaishya traders to Southeast Asia, the most important of which was gold. During the 4th century C.E., when the first evidence of Indian trader in Southeast Asia, the Indian sub-continent was at a deficiency for gold due to extensive control of overland trade routes by the Roman Empire. This made many Vaishya traders look to the seas to acquire new gold, of which Southeast Asia was abundant. However, the conclusion that Indianization was just spread through trade is insufficient, as Indianization permeated through all classes of Southeast Asian society, not just the merchant classes.

Another theory states that Indianization spread through the warrior class of Kshatriya. This hypothesis effectively explains state formation in Southeast Asia, as these warriors came with the intention of conquering the local peoples and establishing their own political power in the region. However, this theory hasn't attracted much interest from historians as there is very little literary evidence to support it.

The most widely accepted theory for the spread of Indianization into Southeast Asia is through the class of Brahman scholars. These Brahmans brought with them many of the Hindu religious and philosophical traditions and spread them to the elite classes of Southeast Asian polities. Once these traditions were adopted into the elite classes, it disseminated throughout all the lower classes, thus explaining the Indianization present in all classes of Southeast Asian society. Brahmans were also experts in art and architecture, and political affairs, thus explaining the adoption of many Indian style law codes and architecture into Southeast Asian society.

Adaption and adoption

It is unknown how immigration, interaction, and settlement took place, whether by key figures from India or through Southeast Asians visiting India who took elements of Indian culture back home. It is likely that Hindu and Buddhist traders, priests, and princes traveled to Southeast Asia from India in the first few centuries of the Common Era and eventually settled there. Strong impulse most certainly came from the region's ruling classes who invited Brahmans to serve at their courts as priests, astrologers and advisers. Divinity and royalty were closely connected in these polities as Hindu rituals validated the powers of the monarch. Brahmans and priests from India proper played a key role in supporting ruling dynasties through exact rituals. Dynastic consolidation was the basis for more centralized kingdoms that emerged in Java, Sumatra, Cambodia, Burma, and along the central and south coasts of Vietnam from the 4th to 8th centuries.

Art, architecture, rituals, and cultural elements such as the Rāmāyaṇa and the Mahābhārata had been adopted and customized increasingly with a regional character. The caste system, although adopted, was never applied universally and reduced to serve for a selected group of nobles only. Many struggle to date and determine when Indianizaton in Southeast Asia occurred because of the structures and ruins found that were similar to those in India.

States such as Srivijaya, Majapahit and the Khmer empire had territorial continuity, resilient population and surplus economies that rivaled those in India itself. Borobudur in Java and Angkor in Cambodia are, apart from their grandeur, examples of a distinctly developed regional culture, style, and expression.

Southeast Asia is called Suvarnabhumi or Sovannah Phoum – the golden land and Suvarnadvipa – the golden Islands in Sanskrit. It was frequented by traders from eastern India, particularly Kalinga. Cultural and trading relations between the powerful Chola dynasty of South India and the Southeast Asian Hindu kingdoms led the Bay of Bengal to be called "The Chola Lake", and the Chola attacks on Srivijaya in the 10th century CE are the sole example of military attacks by Indian rulers against Southeast Asia. The Pala dynasty of Bengal, which controlled the heartland of Buddhist India, maintained close economic, cultural and religious ties, particularly with Srivijaya.

Religion, authority and legitimacy

The pre-Indic political and social systems in Southeast Asia were marked by a relative indifference towards lineage descent. Hindu God kingship enabled rulers to supersede loyalties, forge cosmopolitan polities and the worship of Shiva and Vishnu was combined with ancestor worship, so that Khmer, Javanese, and Cham rulers claimed semi-divine status as descendants of a God. Hindu traditions, especially the relationship to the sacrality of the land and social structures, are inherent in Hinduism's transnational features. The epic traditions of the Mahābhārata and the Rāmāyaṇa further legitimized a ruler identified with a God who battled and defeated the wrong doers that threaten the ethical order of the world.

Hinduism does not have a single historical founder, a centralized imperial authority in India proper nor a bureaucratic structure, thus ensuring relative religious independence for the individual ruler. It also allows for multiple forms of divinity, centered upon the Trimurti the triad of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, the deities responsible for the creation, preservation, and destruction of the universe.

The effects of Hinduism and Buddhism applied a tremendous impact on the many civilizations inhabiting Southeast Asia which significantly provided some structure to the composition of written traditions. An essential factor for the spread and adaptation of these religions originated from trading systems of the third and fourth century. In order to spread the message of these religions Buddhist monks and Hindu priests joined mercantile classes in the quest to share their religious and cultural values and beliefs. Along the Mekong delta, evidence of Indianized religious models can be observed in communities labeled Funan. There can be found the earliest records engraved on a rock in Vocanh. The engravings consist of Buddhist archives and a south Indian scripts are written in Sanskrit that have been dated to belong to the early half of the third century. Indian religion was profoundly absorbed by local cultures that formed their own distinctive variations of these structures in order to reflect their own ideals.

The indianized kingdoms had by the 1st to 4th centuries CE adopted Hinduism's cosmology and rituals, the devaraja concept of kingship, and Sanskrit as official writing. Despite the fundamental cultural integration, these kingdoms were autonomous in their own right and functioned independently.

Waning of Indianization

Khmer Kingdom

Beginning shortly after the 12th century, the Khmer kingdom, one of the first kingdoms that began the dissipation of Indianization started after Jayavarman VII in which expanded a substantial amount of territory, thus going into war with Champa. Leading into the fall of the Khmer Kingdom, the Khmer political and cultural zones were taken, overthrown, and fallen as well. Not only did Indianization change many cultural and political aspects, but it also changed the spiritual realm as well, creating a type of Northern Culture which began in the early 14th century, prevalent for its rapid decline in the Indian kingdoms. The decline of Hinduism kingdoms and spark of Buddhist kingdoms led to the formation of orthodox Sinhalese Buddhism and is a key factor leading to the decline of Indianization. Sukhothai and Ceylon are the prominent characters who formulated the center of Buddhism and this became more popularized over Hinduism.

Rise of Islam

Not only was the spark of Buddhism the driving force for Indianization coming to an end, but Islamic control took over as well in the midst of the thirteenth century to trump the Hinduist kingdoms. In the process of Islam coming to the traditional Hinduism kingdoms, trade was heavily practiced and the now Islamic Indians started becoming merchants all over Southeast Asia. Moreover, as trade became more saturated in the Southeast Asian regions wherein Indianization once persisted, the regions had become more Muslim populated. This so-called Islamic control has spanned to many of the trading centers across the regions of Southeast Asia, including one of the most dominant centers, Malacca, and has therefore stressed a widespread rise of Islamization.

Indianized kingdoms of South East Asia

Mainland kingdoms

- Funan: Funan was a polity that encompassed the southernmost part of the Indochinese peninsula during the 1st to 6th centuries. The name Funan is not found in any texts of local origin from the period, and so is considered an exonym based on the accounts of two Chinese diplomats, Kang Tai and Zhu Ying who sojourned there in the mid-3rd century CE. It is not known what name the people of Funan gave to their polity. Some scholars believe ancient Chinese scholars transcribed the word Funan from a word related to the Khmer word bnaṃ or vnaṃ (modern: phnoṃ, meaning "mountain"); while others thought that Funan may not be a transcription at all, rather it meant what it says in Chinese, meaning something like "Pacified South". Centered at the lower Mekong, Funan is noted as the oldest Hindu culture in this region, which suggests prolonged socio-economic interaction with India and maritime trading partners of the Indosphere. Cultural and religious ideas had reached Funan via the Indian Ocean trade route. Trade with India had commenced well before 500 BC as Sanskrit hadn't yet replaced Pali. Funan's language has been determined as to have been an early form of Khmer and its written form was Sanskrit.

- Chenla was the successor polity of Funan that existed from around the late 6th century until the early 9th century in Indochina, preceding the Khmer Empire. Like its predecessor, Chenla occupied a strategic position where the maritime trade routes of the Indosphere and the East Asian cultural sphere converged, resulting in prolonged socio-economic and cultural influence, along with the adoption of the Sanskrit epigraphic system of the south Indian Pallava dynasty and Chalukya dynasty. Chenla's first ruler Vīravarman adopted the idea of divine kingship and deployed the concept of Harihara, the syncretistic Hindu "god that embodied multiple conceptions of power". His successors continued this tradition, thus obeying the code of conduct Manusmṛti, the Laws of Manu for the Kshatriya warrior caste and conveying the idea of political and religious authority.

- Langkasuka: Langkasuka (-langkha Sanskrit for "resplendent land" -sukkha of "bliss") was an ancient Hindu kingdom located in the Malay Peninsula. The kingdom, along with the Old Kedah settlement, are probably the earliest territorial footholds founded on the Malay Peninsula. According to tradition, the founding of the kingdom happened in the 2nd century; Malay legends claim that Langkasuka was founded at Kedah, and later moved to Pattani.

- Champa: The kingdoms of Champa controlled what is now south and central Vietnam. The earliest kingdom, Lâm Ấp was desbribed by Chinese sources around 192. CE The dominant religion was Hinduism and the culture was heavily influenced by India. By the late fifteenth century, the Vietnamese – proponents of the Sinosphere – had eradicated the last remaining traces of the once powerful maritime kingdom of Champa. The last surviving Chams began their diaspora in 1471, many re-settling in Khmer territory.

- Kambuja: The Khmer Empire was established by the early 9th century in a mythical initiation and consecration ceremony by founder Jayavarman II at Mount Kulen (Mount Mahendra) in 802 CE A succession of powerful sovereigns, continuing the Hindu devaraja tradition, reigned over the classical era of Khmer civilization until the 11th century. Buddhism was then introduced temporarily into royal religious practice, with discontinuities and decentralisation resulting in subsequent removal. The royal chronology ended in the 14th century. During this period of the Khmer empire, societal functions of administration, agriculture, architecture, hydrology, logistics, urban planning, literature and the arts saw an unprecedented degree of development, refinement and accomplishment from the distinct expression of Hindu cosmology.

- Mon kingdoms: From the 9th century until the abrupt end of the Hanthawaddy Kingdom in 1539, the Mon kingdoms (Dvaravati, Hariphunchai, Pegu) were notable for facilitating Indianized cultural exchange in lower Burma, in particular by having strong ties with Sri Lanka.

- Sukhothai: The first Tai peoples to gain independence from the Khmer Empire and start their own kingdom in the 13th century. Sukhothai was a precursor for the Ayutthaya Kingdom and the Kingdom of Siam. Though ethnically Thai, the Sukhothai kingdom in many ways was a continuation of the Buddhist Mon-Dvaravati civilizations, as well as the neighboring Khmer Empire.

Island kingdoms

- Salakanagara: Salakanagara kingdom is the first historically recorded Indianized kingdom in Western Java, established by an Indian trader after marrying a local Sundanese princess. This Kingdom existed between 130 and 362 CE.

- Tarumanagara was an early Sundanese Indianized kingdom, located not far from modern Jakarta, and according to Tugu inscription ruler Purnavarman apparently built a canal that changed the course of the Cakung River, and drained a coastal area for agriculture and settlement. In his inscriptions, Purnavarman associated himself with Vishnu, and Brahmins ritually secured the hydraulic project.

- Kalingga: Kalingga (Javanese: Karajan Kalingga) was the 6th century Indianized kingdom on the north coast of Central Java, Indonesia. It was the earliest Hindu-Buddhist kingdom in Central Java, and together with Kutai and Tarumanagara are the oldest kingdoms in Indonesian history.

- Malayu was a classical Southeast Asian kingdom. The primary sources for much of the information on the kingdom are the New History of the Tang, and the memoirs of the Chinese Buddhist monk Yijing who visited in 671 CE, and states that it was "absorbed" by Srivijaya by 692 CE, but had "broken away" by the end of the eleventh century according to Chao Jukua. The exact location of the kingdom is the subject of studies among historians.

- Srivijaya: From the 7th to 13th centuries Srivijaya, a maritime empire centered on the island of Sumatra in Indonesia, had adopted Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism under a line of rulers from Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa to the Sailendras. A stronghold of Vajrayana Buddhism, Srivijaya attracted pilgrims and scholars from other parts of Asia. I Ching reports that the kingdom was home to more than a thousand Buddhist scholars. A notable Buddhist scholar of local origin, Dharmakirti, taught Buddhist philosophy in Srivijaya and Nalanda (in India), and was the teacher of Atisha. Most of the time, this Buddhist Malay empire enjoyed cordial relationship with China and the Pala Empire in Bengal, and the 860 CE Nalanda inscription records that Maharaja Balaputra dedicated a monastery at Nalanda university near Pala territory. The Srivijaya kingdom ceased to exist in the 13th century due to various factors, including the expansion of the Javanese, Singhasari, and Majapahit empires.

- Tambralinga was an ancient kingdom located on the Malay Peninsula that at one time came under the influence of Srivijaya. The name had been forgotten until scholars recognized Tambralinga as Nagara Sri Dharmaraja (Nakhon Si Thammarat). Early records are scarce but its duration is estimated to range from the seventh to the fourteenth century. Tambralinga first sent tribute to the emperor of the Tang dynasty in 616 CE. In Sanskrit, Tambra means "red" and linga means "symbol", typically representing the divine energy of Shiva.

- Mataram: The Mataram Kingdom flourished between the 8th and 11th centuries. It was first centered in central Java before moving later to east Java. This kingdom produced numbers of Hindu-Buddhist temples in Java, including Borobudur Buddhist mandala and the Prambanan Trimurti Hindu temple dedicated mainly to Shiva. The Sailendras were the ruling family of this kingdom at an earlier stage in central Java, before being replaced by the Isyana Dynasty.

- Kadiri: In the 10th century, Mataram challenged the supremacy of Srivijaya, resulting in the destruction of the Mataram capital by Srivijaya early in the 11th century. Restored by King Airlangga (c. 1020–1050), the kingdom split on his death; the new state of Kediri, in eastern Java, became the centre of Javanese culture for the next two centuries, spreading its influence to the eastern parts of Southeast Asia. The spice trade was now becoming increasingly important, as demand from European countries grew. Before they learned to keep sheep and cattle alive in the winter, they had to eat salted meat, made palatable by the addition of spices. One of the main sources was the Maluku Islands (or "Spice Islands") in Indonesia, and so Kediri became a strong trading nation.

- Singhasari: In the 13th century, however, the Kediri dynasty was overthrown by a revolution, and Singhasari arose in east Java. The domains of this new state expanded under the rule of its warrior-king Kertanegara. He was killed by a prince of the previous Kediri dynasty, who then established the last great Hindu-Javanese kingdom, Majapahit. By the middle of the 14th century Majapahit controlled most of Java, Sumatra and the Malay peninsula, part of Borneo, the southern Celebes and the Moluccas. It also exerted considerable influence on the mainland.

- Majapahit: The Majapahit empire, centered in East Java, succeeded the Singhasari empire and flourished in the Indonesian archipelago between the 13th and 15th centuries. Noted for their naval expansion, the Javanese spanned west–east from Lamuri in Aceh to Wanin in Papua. Majapahit was one of the last and greatest Hindu empires in Maritime Southeast Asia. Most of Balinese Hindu culture, traditions and civilisations were derived from Majapahit legacy. A large number of Majapahit nobles, priests, and artisans found their home in Bali after the decline of Majapahit to Demak Sultanate.

- Galuh was an ancient Hindu kingdom in the eastern Tatar Pasundan (now west Java province and Banyumasan region of central Java province), Indonesia. It was established following the collapse of the Tarumanagara kingdom around the 7th century. Traditionally the kingdom of Galuh was associated with the eastern Priangan cultural region, around the Citanduy and Cimanuk rivers, with its territory spanning from Citarum river on the west, to the Pamali (present-day Brebes river) and Serayu rivers on the east. Its capital was located in Kawali, near present-day Ciamis city.

- Sunda: The Kingdom of Sunda was a Hindu kingdom located in western Java from 669 CE to around 1579 CE, covering the area of present-day Banten, Jakarta, West Java, and the western part of Central Java. According to primary historical records, the Bujangga Manik manuscript, the eastern border of the Sunda Kingdom was the Pamali River (Ci Pamali, the present day Brebes River) and the Serayu River (Ci Sarayu) in Central Java.

Indianized kingdoms of South West Asia

The eastern regions of Afghanistan were considered politically as parts of India. Buddhism and Hinduism held sway over the region until the Muslim conquest. Kabul and Zabulistan which housed Buddhism and other Indian religions, offered stiff resistance to the Muslim advance for two centuries, with the Kabul Shahi and Zunbils remaining unconquered until the Saffarid and Ghaznavid conquests. The significance of the realm of Zun and its rulers Zunbils had laid in them blocking the path of Arabs in invading the Indus Valley.

According to historian André Wink, "In southern and eastern Afghanistan, the regions of Zamindawar (Zamin I Datbar or land of the justice giver, the classical Arachosia) and Zabulistan or Zabul (Jabala, Kapisha, Kia pi shi) and Kabul, the Arabs were effectively opposed for more than two centuries, from 643 to 870 AD, by the indigenous rulers the Zunbils and the related Kabul-Shahs of the dynasty which became known as the Buddhist-Shahi. With Makran and Baluchistan and much of Sindh this area can be reckoned to belong to the cultural and political frontier zone between India and Persia." He also wrote, "It is clear however that in the seventh to ninth centuries the Zunbils and their kinsmen the Kabulshahs ruled over a predominantly Indian rather than a Persianate realm. The Arab geographers, in effect, commonly speak of 'that king of al-Hind ... (who) bore the title of Zunbil."

Archaeological sites such as the 8th-century Tapa Sardar and Gardez show a blend of Buddhism with strong Shaivst iconography. Around 644 CE, the Chinese travelling monk Xuanzang made an account of Zabul (which he called by its Sanskrit name Jaguda), which he describes as mainly pagan, though also respecting Mahayana Buddhism, which although in the minority had the support of its royals. In terms of other cults, the god Śuna, is described to be the prime deity of the country.

The Caliph Al-Ma'mun (r. 813–833 A.D.)led the last Arab expeditions on Kabul and Zabul, after which the long-drawn conflict ended with the dissolution of the empire. Rutbil were made to pay double the tribute to the Caliph. The king of Kabul was captured by him and converted to Islam. The last Zunbil was killed by Ya'qub bin al-Layth along with his former overlord Salih b. al-Nadr in 865. Meanwhile, the Hindu Shahi of Kabul were defeated under Mahmud of Ghazni. Indian soldiers were a part of the Ghaznavid army, Baihaki mentioned Hindu officers employed by Ma'sud. The 14th-century scholar Muslim scholar Ibn Battuta described the Hindu Kush as meaning "slayer of Indians", because large numbers of slaves brought from India died from its treacherous weather.

Zabulistan

Zabulistan, a historical region in southern Afghanistan roughly corresponding to the modern provinces of Zabul and Ghazni, was a collection of loose suzerains of the Hindu rulers when it fell to the Turk Shahis in the 7th century, though the suzerainty continued up to the 11th century. The Hindu kingdom of Kapisha had split up as its western part formed a separate state called the kingdom of Zabul. It was a family division because there were consanguineous and political relationships between the states of Kabul and Zabul.

The Zunbils, a royal dynasty south of the Hindu Kush in present-day southern Afghanistan region, worshiped the Zhuna, possibly a sun god connected to the Hindu god Surya and is sometimes referred to as Zoor or Zoon. He is represented with flames radiating from his head on coins. Statues were adorned with gold and used rubies for eyes. Huen Tsang calls him "sunagir". It has been linked with the Hindu god Aditya at Multan, pre-Buddhist religious and kingship practices of Tibet as well as Shaivism. His shrine lay on a sacred mountain in Zamindawar. Originally it appears to have been brought there by Hepthalites, displacing an earlier god on the same site. Parallels have been noted with the pre-Buddhist monarchy of Tibet, next to Zoroastrian influence on its ritual. Whatever its origins, it was certainly superimposed on a mountain and on a pre-existing mountain god while merging with Shaiva doctrines of worship.

Buddhist Turk Shahi dynasty of Kabul

The area had been under the rule of the Turk Shahi who took over the rule of Kabul in the seventh century and later were attacked by the Arabs. The Turk Shahi dynasty was Buddhist and were followed by a Hindu dynasty shortly before the Saffarid conquest in 870 A.D.

The Turk Shahi were a Buddhist Turkic dynasty that ruled from Kabul and Kapisa in the 7th to 9th centuries. They replaced the Nezak – the last dynasty of Bactrian rulers. Kabulistan was the heartland of the Turk Shahi domain, which at times included Zabulistan and Gandhara. The last Shahi ruler of Kabul, Lagaturman, was deposed by a Brahmin minister, possibly named Vakkadeva, in c. 850, signaling the end of the Buddhist Turk Shahi dynasty, and the beginning of the Hindu Shahi dynasty of Kabul.

Hindu Shahi dynasty of Kabul

The Hindu Shahi (850–1026 CE) was a Hindu dynasty that held sway over the Kabul Valley, Gandhara (modern-day Pakistan and northeastern Afghanistan), and present-day northwestern India, during the early medieval period in the Indian subcontinent. They succeeded the Turk Shahis. There were two successive dynasties in Kabul Valley and Gandhara &ndash the Kshatriya dynasty and the Brahmana dynasty which replaced it. Both used the title of Shahi. Details about these rulers have been assembled from chronicles, coins and stone inscriptions by researchers as no consolidated account of their history has become available. In 1973, Historian Yogendra Mishra proposed that according to Rajatarangini, Hindu Shahis were Kshatriyas.

According to available inscriptions following are the names of Hindu Shahi kings: Vakkadeva, Kamalavarman, Bhimadeva, Jayapala, Anandapala, Trilochanapala and Bhimpala.

- Vakkadeva: According to The Mazare Sharif Inscription of the Time of the Shahi Ruler Veka, recently discovered from northern Afghanistan and reported by the Taxila Institute of Asian Civilisations, Islamabad, Veka (sic.) conquered northern region of Afghanistan 'with eightfold forces' and ruled there. He established a Shiva temple there which was inaugurated by Parimaha Maitya (the Great Minister). He also issued copper coins of the Elephant and Lion type with the legend Shri Vakkadeva. Nine principal issues of Bull and Horseman silver coins and only one issue of corresponding copper coins of Spalapatideva have become available. As many as five Elephant and Lion type of copper coins of Shri Vakkadeva are available and curiously the copper issues of Vakka are contemporaneous with the silver issues of Spalapati.

- Kamalavarman: During the reign of Kamalavarman, the Saffarid rule weakened precipitately and ultimately Sistan became a part of the Samanid Empire. The disorder generally prevailed and the control of Zabulistan changed hands frequently. Taking advantage of the situation, the Shahis stepped up activities on their western frontier. The result was the emergence of a small Hindu power at Ghazni, supported by the Shahis. "The authorities either themselves of early date or enshrining early information mention Lawik", a Hindu, as the ruler at Ghazni, before this place was taken over by the Turkish slave governor of the Samanids.

- Jayapala: With Jayapala, a new dynasty started ruling over the former Shahi kingdom of southeastern Afghanistan and the change over was smooth and consensual. On his coronation, Jayapala used the additional name-suffix Deva from his predecessor's dynasty in addition to the pala name-ending of his own family. (With Kabul lost during the lifetime of Jayapaladeva, his successors – Anandapala, Trilochanapala and Bhimapala – reverted to their own family pala-ending names.) Jayapala did not issue any coins in his own name. Bull and Horseman coins with the legend Samantadeva, in billon, seem to have been struck during Jayapala's reign. As the successor of Bhima, Jayapala was a Shahi monarch of the state of Kabul, which now included Punjab. Minhaj-ud-din describes Jayapala as "the greatest of the Rais of Hindustan."

Balkh

From historical evidence, it appears Tokharistan (Bactria) was the only area heavily colonized by Arabs where Buddhism flourished and the only area incorporated into the Arab empire where Sanskrit studies were pursued up to the conquest. Hui'Chao, who visited around 726, mentions that the Arabs ruled it and all the inhabitants were Buddhists. Balkh's final conquest was undertaken by Qutayba ibn Muslim in 705.[105] Among Balkh's Buddhist monasteries, the largest was Nava Vihara, later Persianized to Naw Bahara after the Islamic conquest of Balkh. It is not known how long it continued to serve as a place of worship after the conquest. Accounts of early Arabs offer contradictory narratives.

Ghur

Amir Suri, a king of the Ghurid dynasty, in the Ghor region of present-day central Afghanistan, and his son Muhammad ibn Suri, despite bearing Arabic names were Buddhists. During their rule from the 9th-century to the 10th-century, they were considered pagans by the surrounding Muslim people, and it was only during the reign of Muhammad's son Abu Ali ibn Muhammad that the Ghurid dynasty became an Islamic dynasty. Amir Suri was a descendant of the Ghurid king Amir Banji, whose rule was legitimized by the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid. He is known to have fought the Saffarid ruler Ya'qub ibn al-Layth al-Saffar, who managed to conquer much of Khurasan except Ghur. Ghur remained a pagan enclave until the 11th century. Mahmud of Ghazni, who raided it, left Muslim precepts to teach Islam to the local population. The region became Muslim by 12th century though the historian Satish Chandra states that Mahayana Buddhism is believed to have existed until the end of the century.

Nuristan

The vast area extending from modern Nuristan to Kashmir (styled "Peristan" by A. M. Cacopardo) containing host of "Kafir" cultures and Indo-European languages that became Islamized over a long period. Earlier, it was surrounded by Buddhist areas. The Islamization of the nearby Badakhshan began in the 8th century and Peristan was completely surrounded by Muslim states in the 16th century with Islamization of Baltistan. The Buddhist states temporarily brought literacy and state rule into the region. The decline of Buddhism resulted in it becoming heavily isolated.

Successive wave of Pashtun immigration, before or during 16th and 17th centuries, displaced the original Kafirs and Pashayi people from Kunar Valley and Laghman valley, the two eastern provinces near Jalalabad, to the less fertile mountains. Before their conversion, the Kafir people of Kafiristan practiced a form of ancient Hinduism infused with locally developed accretions. The region from Nuristan to Kashmir (styled Peristan by A. M. Cacopardo) was host to a vast number of "Kafir" cultures. They were called Kafirs due to their enduring paganism, remaining politically independent until being conquered and forcibly converted by Afghan Amir Abdul Rahman Khan in 1895–1896 while others also converted to avoid paying jizya.

In 1020–21, Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna led a campaign against Kafiristan and the people of the "pleasant valleys of Nur and Qirat" according to Gardizi. These people worshipped the lion. Mohammad Habib however considers they might have been worshipping Buddha in form of a lion (Sakya Sinha). Ramesh Chandra Majumdar states they had a Hindu temple which was destroyed by Mahmud's general.

Indian cultural influence

The use of Greater India to refer to an Indian cultural sphere was popularised by a network of Bengali scholars in the 1920s who were all members of the Calcutta-based Greater India Society. The movement's early leaders included the historian R. C. Majumdar (1888–1980); the philologists Suniti Kumar Chatterji (1890–1977) and P. C. Bagchi (1898–1956), and the historians Phanindranath Bose and Kalidas Nag (1891–1966). Some of their formulations were inspired by concurrent excavations in Angkor by French archaeologists and by the writings of French Indologist Sylvain Lévi. The scholars of the society postulated a benevolent ancient Indian cultural colonisation of Southeast Asia, in stark contrast – in their view – to the Western colonialism of the early 20th century.

The term Greater India and the notion of an explicit Hindu expansion of ancient Southeast Asia have been linked to both Indian nationalism and Hindu nationalism. However, many Indian nationalists, like Jawaharlal Nehru and Rabindranath Tagore, although receptive to "an idealisation of India as a benign and uncoercive world civiliser and font of global enlightenment," stayed away from explicit "Greater India" formulations. In addition, some scholars have seen the Hindu/Buddhist acculturation in ancient Southeast Asia as "a single cultural process in which Southeast Asia was the matrix and South Asia the mediatrix." In the field of art history, especially in American writings, the term survived due to the influence of art theorist Ananda Coomaraswamy. Coomaraswamy's view of pan-Indian art history was influenced by the "Calcutta cultural nationalists."

By some accounts Greater India consists of "lands including Burma, Java, Cambodia, Bali, and the former Champa and Funan polities of present-day Vietnam," in which Indian and Hindu culture left an "imprint in the form of monuments, inscriptions and other traces of the historic "Indianizing" process." By some other accounts, many Pacific societies and "most of the Buddhist world including Ceylon, Tibet, Central Asia, and even Japan were held to fall within this web of Indianizing culture colonies" This particular usage – implying cultural "sphere of influence" of India – was promoted by the Greater India Society, formed by a group of Bengali men of letters, and is not found before the 1920s. The term Greater India was used in historical writing in India into the 1970s.

Cultural expansion

Culture spread via the trade routes that linked India with southern Burma, central and southern Siam, the Malay peninsula and Sumatra to Java, lower Cambodia and Champa. The Pali and Sanskrit languages and the Indian script, together with Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism, Brahmanism and Hinduism, were transmitted from direct contact as well as through sacred texts and Indian literature. Southeast Asia had developed some prosperous and very powerful colonial empires that contributed to Hindu-Buddhist artistic creations and architectural developments. Art and architectural creations that rivaled those built in India, especially in its sheer size, design and aesthetic achievements. The notable examples are Borobudur in Java and Angkor monuments in Cambodia. The Srivijaya Empire to the south and the Khmer Empire to the north competed for influence in the region.

A defining characteristic of the cultural link between Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent was the adoption of ancient Indian Vedic/Hindu and Buddhist culture and philosophy into Myanmar, Tibet, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaya, Laos and Cambodia. Indian scripts are found in Southeast Asian islands ranging from Sumatra, Java, Bali, South Sulawesi and the Philippines. The Ramayana and the Mahabharata have had a large impact on South Asia and Southeast Asia. One of the most tangible evidence of dharmic Hindu traditions is the widespread use of the Añjali Mudrā gesture of greeting and respect. It is seen in the Indian namasté and similar gestures known throughout Southeast Asia; its cognates include the Cambodian sampeah, the Indonesian sembah, the Japanese gassho and Thai wai.

Beyond the Himalaya and Hindukush mountains in the north, along the Silk Route Indian influence was linked with Buddhism. Tibet and Khotan was direct heirs of Gangetic Buddhism, despite the difference in languages. Many Tibetan monks even used to know Sanskrit very well. In Khotan the Ramayana was well cicrulated in Khotanese language, though the narrative is slightly different from the Gangetic version. In Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan many Buddhist monasteries were established. These countries were used as a kind of springboard for the monks who brought Indian Buddhist texts and images to China. Further north, in the Gobi Desert, statues of Ganesha and Kartikeya was found alongside Buddhist imagery in Mogao Caves.

Cultural commonalities

Religion, mythology and folklore

- Hinduism is practised by the majority of Bali's population. The Cham people of Vietnam still practice Hinduism as well. Though officially Buddhist, many Thai, Khmer, and Burmese people also worship Hindu gods in a form of syncretism.

- Brahmins have had a large role in spreading Hinduism in Southeast Asia. Even today many monarchies such as the royal court of Thailand still have Hindu rituals performed for the King by Hindu Brahmins.

- Garuda, a Hindu mythological figure, is present in the coats of arms of Indonesia, Thailand and Ulaanbaatar.

- Muay Thai, a fighting art that is the Thai version of the Hindu Musti-yuddha style of martial art.

- Kaharingan, an indigenous religion followed by the Dayak people of Borneo, is categorised as a form of Hinduism in Indonesia.

- Philippine mythology includes the supreme god Bathala and the concept of Diwata and the still-current belief in Karma—all derived from Hindu-Buddhist concepts.

- Malay folklore contains a rich number of Indian-influenced mythological characters, such as Bidadari, Jentayu, Garuda and Naga.

- Wayang shadow puppets and classical dance-dramas of Indonesia, Cambodia, Malaysia and Thailand took stories from episodes of Ramayana and Mahabharata.

Caste system

Indians spread their religion to Southeast Asia, beginning the Hindu and Buddhist cultures there. They introduced the caste system to the region, especially to Java, Bali, Madura, and Sumatra. The adopted caste system was not as strict as in India, tempered to the local context. There are multiple similarities between the two caste systems such that both state that no one is equal within society and that everyone has his own place. It also promoted the upbringing of highly organized central states. Indians were still able to implement their religion, political ideas, literature, mythology, and art.

Architecture and monuments

- The same style of Hindu temple architecture was used in several ancient temples in South East Asia including Angkor Wat, which was dedicated to Hindu god Vishnu and is shown on the flag of Cambodia, also Prambanan in Central Java, the largest Hindu temple in Indonesia, is dedicated to Trimurti — Shiva, Vishnu and Brahma.

- Borobudur in Central Java, Indonesia, is the world's largest Buddhist monument. It took shape of a giant stone mandala crowned with stupas and believed to be the combination of Indian-origin Buddhist ideas with the previous megalithic tradition of native Austronesian step pyramid.

- The minarets of 15th- to 16th-century mosques in Indonesia, such as the Great Mosque of Demak and Kudus mosque resemble those of Majapahit Hindu temples.

- The Batu Caves in Malaysia are one of the most popular Hindu shrines outside India. It is the focal point of the annual Thaipusam festival in Malaysia and attracts over 1.5 million pilgrims, making it one of the largest religious gatherings in history.

- Erawan Shrine, dedicated to Brahma, is one of the most popular religious shrines in Thailand.

Linguistic influence

Scholars like Sheldon Pollock have used the term Sanskrit Cosmopolis to describe the region and argued for millennium-long cultural exchanges without necessarily involving migration of peoples or colonisation. Pollock's 2006 book The Language of the Gods in the World of Men makes a case for studying the region as comparable with Latin Europe and argues that the Sanskrit language was its unifying element.

Scripts in Sanskrit discovered during the early centuries of the Common Era are the earliest known forms of writing to have extended all the way to Southeast Asia. Its gradual impact ultimately resulted in its widespread domain as a means of dialect which evident in regions, from Bangladesh to Cambodia, Malaysia and Thailand and additionally a few of the larger Indonesian islands. In addition, alphabets from languages spoken in Burmese, Thai, Laos, and Cambodia are variations formed off of Indian ideals that have localized the language.

The spread of Buddhism to Tibet allowed many Sanskrit texts to survive only in Tibetan translation (in the Tanjur). Buddhism was similarly introduced to China by Mahayanist missionaries sent by the Indian Emperor Ashoka mostly through translations of Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit and Classical Sanskrit texts, and many terms were transliterated directly and added to the Chinese vocabulary.

In Southeast Asia, languages such as Thai and Lao contain many loan words from Sanskrit, as does Khmer to a lesser extent. For example, in Thai, Rāvaṇa, the legendary emperor of Sri Lanka, is called 'Thosakanth' which is derived from his Sanskrit name 'Daśakaṇṭha' ("having ten necks").

Many Sanskrit loanwords are also found in Austronesian languages, such as Javanese particularly the old form from which nearly half the vocabulary is derived from the language. Other Austronesian languages, such as traditional Malay, modern Indonesian, also derive much of their vocabulary from Sanskrit, albeit to a lesser extent, with a large proportion of words being derived from Arabic. Similarly, Philippine languages such as Tagalog have many Sanskrit loanwords.

A Sanskrit loanword encountered in many Southeast Asian languages is the word bhāṣā, or spoken language, which is used to mean language in general, for example bahasa in Malay, Indonesian and Tausug, basa in Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese, phasa in Thai and Lao, bhasa in Burmese, and phiesa in Khmer.

The utilization of Sanskrit has been prevalent in all aspects of life including legal purposes. Sanskrit terminology and vernacular appears in ancient courts to establish procedures that have been structured by Indian models such as a system composed of a code of laws. The concept of legislation demonstrated through codes of law and organizations particularly the idea of "God King" was embraced by numerous rulers of Southeast Asia. The rulers amid this time, for example, the Lin-I Dynasty of Vietnam once embraced the Sanskrit dialect and devoted sanctuaries to the Indian divinity Shiva. Many rulers following even viewed themselves as "reincarnations or descendants" of the Hindu gods. However once Buddhism began entering the nations, this practiced view was eventually altered.

Literature

Scripts in Sanskrit discovered during the early centuries of the Common Era are the earliest known forms of writing to have extended all the way to Southeast Asia. Its gradual impact ultimately resulted in its widespread domain as a means of dialect which evident in regions, from Bangladesh to Cambodia, Malaysia and Thailand and additionally a few of the larger Indonesian islands. In addition, alphabets from languages spoken in Burmese, Thai, Laos, and Cambodia are variations formed off of Indian ideals that have localized the language.

The utilization of Sanskrit has been prevalent in all aspects of life including legal purposes. Sanskrit terminology and vernacular appears in ancient courts to establish procedures that have been structured by Indian models such as a system composed of a code of laws. The concept of legislation demonstrated through codes of law and organizations particularly the idea of "God King" was embraced by numerous rulers of Southeast Asia. The rulers amid this time, for example, the Lin-I Dynasty of Vietnam once embraced the Sanskrit dialect and devoted sanctuaries to the Indian divinity, Shiva. Many rulers following even viewed themselves as "reincarnations or descendants" of the Hindu Gods. However, once Buddhism began entering the nations, this practiced view was eventually altered.

Linguistic commonalities

- In the Malay Archipelago: Indonesian, Javanese and Malay have absorbed a large amount of Sanskrit loanwords into their respective lexicons (see: Sanskrit loan words in Indonesian). Many languages of native lowland Filipinos such as Tagalog, Ilocano and Visayan contain numerous Sanskrit loanwords.

- In Mainland Southeast Asia: Thai, Lao, Burmese, and Khmer language have absorbed a significant amount of Sanskrit as well as Pali words.

- Many Indonesian names have Sanskrit origin (e.g. Dewi Sartika, Megawati Sukarnoputri, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, Teuku Wisnu).

- Southeast Asian languages are traditionally written with Indic alphabets and therefore have extra letters not pronounced in the local language, so that original Sanskrit spelling can be preserved. An example is how the name of the late King of Thailand, Bhumibol Adulyadej, is spelled in Sanskrit as "Bhumibol"ภูมิพล, yet is pronounced in Thai as "Phumipon" พูมิพน using Thai-Sanskrit pronunciation rules since the original Sanskrit sounds do not exist in Thai.

Toponyms

- Suvarnabhumi is a toponym that has been historically associated with Southeast Asia. In Sanskrit, it means "The Land of Gold". Thailand's Suvarnabhumi Airport is named after this toponym.

- Several of Indonesian toponyms have Indian parallel or origin, such as Madura with Mathura, Serayu and Sarayu river, Semeru with Sumeru mountain, Kalingga from Kalinga Kingdom, and Ngayogyakarta from Ayodhya.

- Siamese ancient city of Ayutthaya also derived from Ramayana's Ayodhya.

- Names of places could simply render their Sanskrit origin, such as Singapore, from Singapura (Singha-pura the "lion city"), Jakarta from Jaya and kreta ("complete victory").

- Some of the Indonesian regencies such as Indragiri Hulu and Indragiri Hilir derived from Indragiri River, Indragiri itself means "mountain of Indra".

- Some Thai toponyms also often have Indian parallels or Sanskrit origin, although the spellings are adapted to the Siamese tongue, such as Ratchaburi from Raja-puri ("king's city"), and Nakhon Si Thammarat from Nagara Sri Dharmaraja.

- The tendency to use Sanskrit for modern neologism also continued to modern day. In 1962 Indonesia changed the colonial name of New Guinean city of Hollandia to Jayapura ("glorious city"), Orange mountain range to Jayawijaya Mountains.

- Malaysia named their new government seat as Putrajaya ("prince of glory") in 1999.