From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Pocket stereoscope with original test image. Used by military to examine stereoscopic pairs of

aerial photographs.

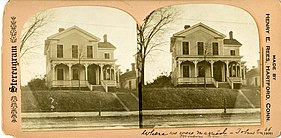

View of Boston, c. 1860; an early stereoscopic card for viewing a scene from nature

Stereoscopic image of 787 Orange Street, Addison R. Tinsley house, circa 1890s.

Stereoscopic image of 772 College Street (formerly Johnson Street) in Macon, Ga, circa 1870s.

Kaiserpanorama consists of a multi-station viewing apparatus and sets of stereo slides. Patented by A. Fuhrmann around 1890.

A company of ladies looking at stereoscopic views, painting by

Jacob Spoel, before 1868. An early depiction of people using a stereoscope.

Stereoscopy (also called stereoscopics, or stereo imaging) is a technique for creating or enhancing the illusion of depth in an image by means of stereopsis for binocular vision. The word stereoscopy derives from Greek στερεός (stereos) 'firm, solid', and σκοπέω (skopeō) 'to look, to see'. Any stereoscopic image is called a stereogram. Originally, stereogram referred to a pair of stereo images which could be viewed using a stereoscope.

Most stereoscopic methods present two offset images separately to the left and right eye of the viewer. These two-dimensional images are then combined in the brain to give the perception of 3D depth. This technique is distinguished from 3D displays that display an image in three full dimensions, allowing the observer to increase information about the 3-dimensional objects being displayed by head and eye movements.

Background

Stereoscopy creates the illusion of three-dimensional depth from given two-dimensional images.

Human vision, including the perception of depth, is a complex process,

which only begins with the acquisition of visual information taken in

through the eyes; much processing ensues within the brain, as it strives

to make sense of the raw information. One of the functions that occur

within the brain as it interprets what the eyes see is assessing the

relative distances of objects from the viewer, and the depth dimension

of those objects. The cues that the brain uses to gauge relative distances and depth in a perceived scene include

- Stereopsis

- Accommodation of the eye

- Overlapping of one object by another

- Subtended visual angle of an object of known size

- Linear perspective (convergence of parallel edges)

- Vertical position (objects closer to the horizon in the scene tend to be perceived as farther away)

- Haze or contrast, saturation, and color, greater distance generally

being associated with greater haze, desaturation, and a shift toward

blue

- Change in size of textured pattern detail

(All but the first two of the above cues exist in traditional

two-dimensional images, such as paintings, photographs, and television.)

Stereoscopy is the production of the illusion of depth in a photograph, movie, or other two-dimensional image by the presentation of a slightly different image to each eye, which adds the first of these cues (stereopsis). The two images are then combined in the brain to give the perception

of depth. Because all points in the image produced by stereoscopy focus

at the same plane regardless of their depth in the original scene, the

second cue, focus, is not duplicated and therefore the illusion of depth

is incomplete. There are also mainly two effects of stereoscopy that

are unnatural for human vision: (1) the mismatch between convergence and

accommodation, caused by the difference between an object's perceived

position in front of or behind the display or screen and the real origin

of that light; and (2) possible crosstalk between the eyes, caused by

imperfect image separation in some methods of stereoscopy.

Although the term "3D" is ubiquitously used, the presentation of

dual 2D images is distinctly different from displaying an image in three full dimensions.

The most notable difference is that, in the case of "3D" displays, the

observer's head and eye movement do not change the information received

about the 3-dimensional objects being viewed. Holographic displays and volumetric display

do not have this limitation. Just as it is not possible to recreate a

full 3-dimensional sound field with just two stereophonic speakers, it

is an overstatement to call dual 2D images "3D". The accurate term

"stereoscopic" is more cumbersome than the common misnomer "3D", which

has been entrenched by many decades of unquestioned misuse. Although

most stereoscopic displays do not qualify as real 3D display, all real

3D displays are also stereoscopic displays because they meet the lower

criteria also.

Most 3D displays use this stereoscopic method to convey images. It was first invented by Sir Charles Wheatstone in 1838,

and improved by Sir David Brewster who made the first portable 3D viewing device.

Wheatstone mirror stereoscope

Brewster-type stereoscope, 1870

Wheatstone originally used his stereoscope (a rather bulky device)

with drawings because photography was not yet available, yet his

original paper seems to foresee the development of a realistic imaging

method:

For the purposes of illustration I have employed only

outline figures, for had either shading or colouring been introduced it

might be supposed that the effect was wholly or in part due to these

circumstances, whereas by leaving them out of consideration no room is

left to doubt that the entire effect of relief is owing to the

simultaneous perception of the two monocular projections, one on each

retina. But if it be required to obtain the most faithful resemblances

of real objects, shadowing and colouring may properly be employed to

heighten the effects. Careful attention would enable an artist to draw

and paint the two component pictures, so as to present to the mind of

the observer, in the resultant perception, perfect identity with the

object represented. Flowers, crystals, busts, vases, instruments of

various kinds, &c., might thus be represented so as not to be

distinguished by sight from the real objects themselves.

Stereoscopy is used in photogrammetry

and also for entertainment through the production of stereograms.

Stereoscopy is useful in viewing images rendered from large multi-dimensional data sets such as are produced by experimental data. Modern industrial three-dimensional photography may use 3D scanners to detect and record three-dimensional information. The three-dimensional depth information can be reconstructed from two images using a computer by correlating the pixels in the left and right images. Solving the Correspondence problem in the field of Computer Vision aims to create meaningful depth information from two images.

Visual requirements

Anatomically, there are 3 levels of binocular vision required to view stereo images:

- Simultaneous perception

- Fusion (binocular 'single' vision)

- Stereopsis

These functions develop in early childhood. Some people who have strabismus disrupt the development of stereopsis, however orthoptics treatment can be used to improve binocular vision. A person's stereoacuity

determines the minimum image disparity they can perceive as depth. It

is believed that approximately 12% of people are unable to properly see

3D images, due to a variety of medical conditions.

According to another experiment up to 30% of people have very weak

stereoscopic vision preventing them from depth perception based on

stereo disparity. This nullifies or greatly decreases immersion effects

of stereo to them.

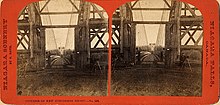

Saul Davis (act. 1860s–1870s), New Suspension Bridge, Niagara Falls, Canada, c. 1869, albumen print stereograph,

Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC

Stereoscopic viewing may be artificially created by the viewer's brain, as demonstrated with the Van Hare Effect,

where the brain perceives stereo images even when the paired

photographs are identical. This "false dimensionality" results from the

developed stereoacuity in the brain, allowing the viewer to fill in

depth information even when few if any 3D cues are actually available in

the paired images.

Side-by-side

Traditional stereoscopic photography consists of creating a 3D

illusion starting from a pair of 2D images, a stereogram. The easiest

way to enhance depth perception in the brain is to provide the eyes of the viewer with two different images, representing two perspectives of the same object, with a minor deviation equal or nearly equal to the perspectives that both eyes naturally receive in binocular vision.

A stereoscopic pair of images (top) and a combined

anaglyph that colors one perspective red and the other

cyan.

3D red cyan glasses are recommended to view this image correctly.

3D red cyan glasses are recommended to view this image correctly.

Two Passiflora caerulea flowers arranged as a stereo image pair for viewing by the cross-eyed viewing method (see Freeviewing)

To avoid eyestrain and distortion, each of the two 2D images should

be presented to the viewer so that any object at infinite distance is

perceived by the eye as being straight ahead, the viewer's eyes being

neither crossed nor diverging. When the picture contains no object at

infinite distance, such as a horizon or a cloud, the pictures should be

spaced correspondingly closer together.

The advantages of side-by-side viewers is the lack of diminution

of brightness, allowing the presentation of images at very high

resolution and in full spectrum color, simplicity in creation, and

little or no additional image processing is required. Under some

circumstances, such as when a pair of images is presented for

freeviewing, no device or additional optical equipment is needed.

The principal disadvantage of side-by-side viewers is that large image

displays are not practical and resolution is limited by the lesser of

the display medium or human eye. This is because as the dimensions of an

image are increased, either the viewing apparatus or viewer themselves

must move proportionately further away from it in order to view it

comfortably. Moving closer to an image in order to see more detail would

only be possible with viewing equipment that adjusted to the

difference.

Printable cross eye viewer.

Freeviewing

Freeviewing is viewing a side-by-side image pair without using a viewing device.

Two methods are available to freeview:

- The parallel viewing method uses an image pair with the left-eye

image on the left and the right-eye image on the right. The fused

three-dimensional image appears larger and more distant than the two

actual images, making it possible to convincingly simulate a life-size

scene. The viewer attempts to look through the images with the

eyes substantially parallel, as if looking at the actual scene. This can

be difficult with normal vision because eye focus and binocular

convergence are habitually coordinated. One approach to decoupling the

two functions is to view the image pair extremely close up with

completely relaxed eyes, making no attempt to focus clearly but simply

achieving comfortable stereoscopic fusion of the two blurry images by

the "look-through" approach, and only then exerting the effort to focus

them more clearly, increasing the viewing distance as necessary.

Regardless of the approach used or the image medium, for comfortable

viewing and stereoscopic accuracy the size and spacing of the images

should be such that the corresponding points of very distant objects in

the scene are separated by the same distance as the viewer's eyes, but

not more; the average interocular distance is about 63 mm. Viewing much

more widely separated images is possible, but because the eyes never

diverge in normal use it usually requires some previous training and

tends to cause eye strain.

- The cross-eyed viewing method swaps the left and right eye images so

that they will be correctly seen cross-eyed, the left eye viewing the

image on the right and vice versa. The fused three-dimensional image

appears to be smaller and closer than the actual images, so that large

objects and scenes appear miniaturized. This method is usually easier

for freeviewing novices. As an aid to fusion, a fingertip can be placed

just below the division between the two images, then slowly brought

straight toward the viewer's eyes, keeping the eyes directed at the

fingertip; at a certain distance, a fused three-dimensional image should

seem to be hovering just above the finger. Alternatively, a piece of

paper with a small opening cut into it can be used in a similar manner;

when correctly positioned between the image pair and the viewer's eyes,

it will seem to frame a small three-dimensional image.

Prismatic, self-masking glasses are now being used by some

cross-eyed-view advocates. These reduce the degree of convergence

required and allow large images to be displayed. However, any viewing

aid that uses prisms, mirrors or lenses to assist fusion or focus is

simply a type of stereoscope, excluded by the customary definition of

freeviewing.

Stereoscopically fusing two separate images without the aid of

mirrors or prisms while simultaneously keeping them in sharp focus

without the aid of suitable viewing lenses inevitably requires an

unnatural combination of eye vergence and accommodation.

Simple freeviewing therefore cannot accurately reproduce the

physiological depth cues of the real-world viewing experience. Different

individuals may experience differing degrees of ease and comfort in

achieving fusion and good focus, as well as differing tendencies to eye

fatigue or strain.

Autostereogram

An autostereogram is a single-image stereogram (SIS), designed to create the visual illusion of a three-dimensional (3D) scene within the human brain from an external two-dimensional image. In order to perceive 3D shapes in these autostereograms, one must overcome the normally automatic coordination between focusing and vergence.

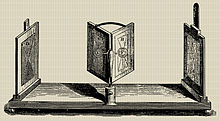

Stereoscope and stereographic cards

The stereoscope is essentially an instrument in which two photographs

of the same object, taken from slightly different angles, are

simultaneously presented, one to each eye. A simple stereoscope is

limited in the size of the image that may be used. A more complex

stereoscope uses a pair of horizontal periscope-like

devices, allowing the use of larger images that can present more

detailed information in a wider field of view. One can buy historical

stereoscopes such as Holmes stereoscopes as antiques. Many stereo

photography artists like Jim Naughten and Rebecca Hackemann also make

their own stereoscopes.

Transparency viewers

A View-Master Model E of the 1950s

Some stereoscopes are designed for viewing transparent photographs on film or glass, known as transparencies or diapositives and commonly called slides.

Some of the earliest stereoscope views, issued in the 1850s, were on

glass. In the early 20th century, 45x107 mm and 6x13 cm glass slides

were common formats for amateur stereo photography, especially in

Europe. In later years, several film-based formats were in use. The

best-known formats for commercially issued stereo views on film are Tru-Vue, introduced in 1931, and View-Master, introduced in 1939 and still in production. For amateur stereo slides, the Stereo Realist format, introduced in 1947, is by far the most common.

Head-mounted displays

An

HMD with a separate video source displayed in front of each eye to achieve a stereoscopic effect

The user typically wears a helmet or glasses with two small LCD or OLED

displays with magnifying lenses, one for each eye. The technology can

be used to show stereo films, images or games, but it can also be used

to create a virtual display. Head-mounted displays may also be

coupled with head-tracking devices, allowing the user to "look around"

the virtual world by moving their head, eliminating the need for a

separate controller. Performing this update quickly enough to avoid

inducing nausea in the user requires a great amount of computer image

processing. If six axis position sensing (direction and position) is

used then wearer may move about within the limitations of the equipment

used. Owing to rapid advancements in computer graphics and the

continuing miniaturization of video and other equipment these devices

are beginning to become available at more reasonable cost.

Head-mounted or wearable glasses may be used to view a

see-through image imposed upon the real world view, creating what is

called augmented reality.

This is done by reflecting the video images through partially

reflective mirrors. The real world view is seen through the mirrors'

reflective surface. Experimental systems have been used for gaming,

where virtual opponents may peek from real windows as a player moves

about. This type of system is expected to have wide application in the

maintenance of complex systems, as it can give a technician what is

effectively "x-ray vision" by combining computer graphics rendering of

hidden elements with the technician's natural vision. Additionally,

technical data and schematic diagrams may be delivered to this same

equipment, eliminating the need to obtain and carry bulky paper

documents.

Augmented stereoscopic vision is also expected to have

applications in surgery, as it allows the combination of radiographic

data (CAT scans and MRI imaging) with the surgeon's vision.

Virtual retinal displays

A virtual retinal display (VRD), also known as a retinal scan display

(RSD) or retinal projector (RP), not to be confused with a "Retina Display", is a display technology that draws a raster image (like a television picture) directly onto the retina

of the eye. The user sees what appears to be a conventional display

floating in space in front of them. For true stereoscopy, each eye must

be provided with its own discrete display. To produce a virtual display

that occupies a usefully large visual angle but does not involve the use

of relatively large lenses or mirrors, the light source must be very

close to the eye. A contact lens incorporating one or more semiconductor

light sources is the form most commonly proposed. As of 2013, the

inclusion of suitable light-beam-scanning means in a contact lens is

still very problematic, as is the alternative of embedding a reasonably

transparent array of hundreds of thousands (or millions, for HD

resolution) of accurately aligned sources of collimated light.

A pair of LC shutter glasses used to view XpanD 3D films. The thick frames conceal the electronics and batteries.

RealD circular polarized glasses

3D viewers

"3D viewer" redirects here. For Microsoft Store app bundled with Windows 10, see

Microsoft 3D Viewer.

There are two categories of 3D viewer technology, active and passive.

Active viewers have electronics which interact with a display. Passive

viewers filter constant streams of binocular input to the appropriate

eye.

Active

Shutter systems

Functional principle of active shutter 3D systems

A shutter system works by openly presenting the image intended for

the left eye while blocking the right eye's view, then presenting the

right-eye image while blocking the left eye, and repeating this so

rapidly that the interruptions do not interfere with the perceived

fusion of the two images into a single 3D image. It generally uses

liquid crystal shutter glasses. Each eye's glass contains a liquid

crystal layer which has the property of becoming dark when voltage is

applied, being otherwise transparent. The glasses are controlled by a

timing signal that allows the glasses to alternately darken over one

eye, and then the other, in synchronization with the refresh rate of the

screen. The main drawback of active shutters is that most 3D videos and

movies were shot with simultaneous left and right views, so that it

introduces a "time parallax" for anything side-moving: for instance,

someone walking at 3.4 mph will be seen 20% too close or 25% too remote

in the most current case of a 2x60 Hz projection.

Passive

Polarization systems

Functional principle of polarized 3D systems

To present stereoscopic pictures, two images are projected superimposed onto the same screen through polarizing filters or presented on a display

with polarized filters. For projection, a silver screen is used so that

polarization is preserved. On most passive displays every other row of

pixels is polarized for one eye or the other.

This method is also known as being interlaced. The viewer wears

low-cost eyeglasses which also contain a pair of opposite polarizing

filters. As each filter only passes light which is similarly polarized

and blocks the opposite polarized light, each eye only sees one of the

images, and the effect is achieved.

Interference filter systems

This technique uses specific wavelengths of red, green, and blue for

the right eye, and different wavelengths of red, green, and blue for the

left eye. Eyeglasses which filter out the very specific wavelengths

allow the wearer to see a full color 3D image. It is also known as spectral comb filtering or wavelength multiplex visualization or super-anaglyph. Dolby 3D uses this principle. The Omega 3D/Panavision 3D system has also used an improved version of this technology

In June 2012 the Omega 3D/Panavision 3D system was discontinued by DPVO

Theatrical, who marketed it on behalf of Panavision, citing ″challenging

global economic and 3D market conditions″.

Color anaglyph systems

Anaglyph 3D is the name given to the stereoscopic 3D effect achieved

by means of encoding each eye's image using filters of different

(usually chromatically opposite) colors, typically red and cyan.

Red-cyan filters can be used because our vision processing systems use

red and cyan comparisons, as well as blue and yellow, to determine the

color and contours of objects. Anaglyph 3D images contain two

differently filtered colored images, one for each eye. When viewed

through the "color-coded" "anaglyph glasses", each of the two images

reaches one eye, revealing an integrated stereoscopic image. The visual cortex of the brain fuses this into perception of a three dimensional scene or composition.

Chromadepth system

ChromaDepth glasses with prism-like film

The ChromaDepth procedure of American Paper Optics is based on the

fact that with a prism, colors are separated by varying degrees. The

ChromaDepth eyeglasses contain special view foils, which consist of

microscopically small prisms. This causes the image to be translated a

certain amount that depends on its color. If one uses a prism foil now

with one eye but not on the other eye, then the two seen pictures –

depending upon color – are more or less widely separated. The brain

produces the spatial impression from this difference. The advantage of

this technology consists above all of the fact that one can regard

ChromaDepth pictures also without eyeglasses (thus two-dimensional)

problem-free (unlike with two-color anaglyph). However the colors are

only limitedly selectable, since they contain the depth information of

the picture. If one changes the color of an object, then its observed

distance will also be changed.

Pulfrich method

The Pulfrich effect is based on the phenomenon of the human eye

processing images more slowly when there is less light, as when looking

through a dark lens.

Because the Pulfrich effect depends on motion in a particular direction

to instigate the illusion of depth, it is not useful as a general

stereoscopic technique. For example, it cannot be used to show a

stationary object apparently extending into or out of the screen;

similarly, objects moving vertically will not be seen as moving in

depth. Incidental movement of objects will create spurious artifacts,

and these incidental effects will be seen as artificial depth not

related to actual depth in the scene.

Over/under format

Stereoscopic

viewing is achieved by placing an image pair one above one another.

Special viewers are made for over/under format that tilt the right

eyesight slightly up and the left eyesight slightly down. The most

common one with mirrors is the View Magic. Another with prismatic glasses is the KMQ viewer. A recent usage of this technique is the openKMQ project.

Other display methods without viewers

Autostereoscopy

The

Nintendo 3DS uses parallax barrier autostereoscopy to display a 3D image.

Autostereoscopic display technologies use optical components in the

display, rather than worn by the user, to enable each eye to see a

different image. Because headgear is not required, it is also called

"glasses-free 3D". The optics split the images directionally into the

viewer's eyes, so the display viewing geometry requires limited head

positions that will achieve the stereoscopic effect. Automultiscopic

displays provide multiple views of the same scene, rather than just two.

Each view is visible from a different range of positions in front of

the display. This allows the viewer to move left-right in front of the

display and see the correct view from any position. The technology

includes two broad classes of displays: those that use head-tracking to

ensure that each of the viewer's two eyes sees a different image on the

screen, and those that display multiple views so that the display does

not need to know where the viewers' eyes are directed. Examples of

autostereoscopic displays technology include lenticular lens, parallax barrier, volumetric display, holography and light field displays.

Holography

Laser holography, in its original "pure" form of the photographic transmission hologram,

is the only technology yet created which can reproduce an object or

scene with such complete realism that the reproduction is visually

indistinguishable from the original, given the original lighting

conditions. It creates a light field identical to that which emanated from the original scene, with parallax

about all axes and a very wide viewing angle. The eye differentially

focuses objects at different distances and subject detail is preserved

down to the microscopic level. The effect is exactly like looking

through a window. Unfortunately, this "pure" form requires the subject

to be laser-lit and completely motionless—to within a minor fraction of

the wavelength of light—during the photographic exposure, and laser

light must be used to properly view the results. Most people have never

seen a laser-lit transmission hologram. The types of holograms commonly

encountered have seriously compromised image quality so that ordinary

white light can be used for viewing, and non-holographic intermediate

imaging processes are almost always resorted to, as an alternative to

using powerful and hazardous pulsed lasers, when living subjects are

photographed.

Although the original photographic processes have proven

impractical for general use, the combination of computer-generated

holograms (CGH) and optoelectronic holographic displays, both under

development for many years, has the potential to transform the

half-century-old pipe dream of holographic 3D television into a reality;

so far, however, the large amount of calculation required to generate

just one detailed hologram, and the huge bandwidth required to transmit a

stream of them, have confined this technology to the research

laboratory.

In 2013, a Silicon Valley company, LEIA Inc, started manufacturing holographic displays well suited for mobile devices (watches, smartphones or tablets) using a multi-directional backlight and allowing a wide full-parallax angle view to see 3D content without the need of glasses.

Volumetric displays

Volumetric displays use some physical mechanism to display points of light within a volume. Such displays use voxels instead of pixels.

Volumetric displays include multiplanar displays, which have multiple

display planes stacked up, and rotating panel displays, where a rotating

panel sweeps out a volume.

Other technologies have been developed to project light dots in

the air above a device. An infrared laser is focused on the destination

in space, generating a small bubble of plasma which emits visible light.

Integral imaging

Integral imaging is a technique for producing 3D displays which are both autostereoscopic and multiscopic,

meaning that the 3D image is viewed without the use of special glasses

and different aspects are seen when it is viewed from positions that

differ either horizontally or vertically. This is achieved by using an

array of microlenses (akin to a lenticular lens, but an X–Y or "fly's eye" array in which each lenslet typically forms its own image of the scene without assistance from a larger objective lens) or pinholes to capture and display the scene as a 4D light field, producing stereoscopic images that exhibit realistic alterations of parallax and perspective when the viewer moves left, right, up, down, closer, or farther away.

Wiggle stereoscopy

Wiggle stereoscopy is an image display technique achieved by quickly

alternating display of left and right sides of a stereogram. Found in animated GIF format on the web, online examples are visible in the New-York Public Library stereogram collection. The technique is also known as "Piku-Piku".

Stereo photography techniques

For general purpose stereo photography, where the goal is to

duplicate natural human vision and give a visual impression as close as

possible to actually being there, the correct baseline (distance between

where the right and left images are taken) would be the same as the

distance between the eyes.

When images taken with such a baseline are viewed using a viewing

method that duplicates the conditions under which the picture is taken,

then the result would be an image much the same as that which would be

seen at the site the photo was taken. This could be described as "ortho

stereo."

However, there are situations in which it might be desirable to

use a longer or shorter baseline. The factors to consider include the

viewing method to be used and the goal in taking the picture. The

concept of baseline also applies to other branches of stereography, such

as stereo drawings and computer generated stereo images, but it involves the point of view chosen rather than actual physical separation of cameras or lenses.

Stereo window

The

concept of the stereo window is always important, since the window is

the stereoscopic image of the external boundaries of left and right

views constituting the stereoscopic image. If any object, which is cut

off by lateral sides of the window, is placed in front of it, an effect

results that is unnatural and is undesirable, this is called a "window

violation". This can best be understood by returning to the analogy of

an actual physical window. Therefore, there is a contradiction between

two different depth cues: some elements of the image are hidden by the

window, so that the window appears as closer than these elements, and

the same elements of the image appear as closer than the window. So that

the stereo window must always be adjusted to avoid window violations.

Some objects can be seen in front of the window, as far as they

don't reach the lateral sides of the window. But these objects can not

be seen as too close, since there is always a limit of the parallax

range for comfortable viewing.

If a scene is viewed through a window the entire scene would

normally be behind the window, if the scene is distant, it would be some

distance behind the window, if it is nearby, it would appear to be just

beyond the window. An object smaller than the window itself could even

go through the window and appear partially or completely in front of

it. The same applies to a part of a larger object that is smaller than

the window. The goal of setting the stereo window is to duplicate this

effect.

Therefore, the location of the window versus the whole of the

image must be adjusted so that most of the image is seen beyond the

window. In the case of viewing on a 3D TV set, it is easier to place the

window in front of the image, and to let the window in the plane of the

screen.

On the contrary, in the case of projection on a much larger

screen, it is much better to set the window in front of the screen (it

is called "floating window"), for instance so that it is viewed about

two meters away by the viewers sit in the first row. Therefore, these

people will normally see the background of the image at the infinite. Of

course the viewers seated beyond will see the window more remote, but

if the image is made in normal conditions, so that the first row viewers

see this background at the infinite, the other viewers, seated behind,

will also see this background at the infinite, since the parallax of

this background is equal to the average human interocular.

The entire scene, including the window, can be moved backwards or

forwards in depth, by horizontally sliding the left and right eye views

relative to each other. Moving either or both images away from the

center will bring the whole scene away from the viewer, whereas moving

either or both images toward the center will move the whole scene toward

the viewer. This is possible, for instance, if two projectors are used

for this projection.

In stereo photography window adjustments is accomplished by

shifting/cropping the images, in other forms of stereoscopy such as

drawings and computer generated images the window is built into the

design of the images as they are generated.

The images can be cropped creatively to create a stereo window

that is not necessarily rectangular or lying on a flat plane

perpendicular to the viewer's line of sight. The edges of the stereo

frame can be straight or curved and, when viewed in 3D, can flow toward

or away from the viewer and through the scene. These designed stereo

frames can help emphasize certain elements in the stereo image or can be

an artistic component of the stereo image.

Uses

While stereoscopic images have typically been used for amusement, including stereographic cards, 3D films, 3D television, stereoscopic video games,[29] printings using anaglyph and pictures, posters and books of autostereograms, there are also other uses of this technology.

Art

Salvador Dalí

created some impressive stereograms in his exploration in a variety of

optical illusions. Other stereo artists include Zoe Beloff, Christopher

Schneberger, Rebecca Hackemann, William Kentridge, and Jim Naughten. Red-and-cyan anaglyph stereoscopic images have also been painted by hand.

Education

In

the 19th century, it was realized that stereoscopic images provided an

opportunity for people to experience places and things far away, and

many tour sets were produced, and books were published allowing people

to learn about geography, science, history, and other subjects. Such uses continued till the mid-20th century, with the Keystone View Company producing cards into the 1960s.

Space exploration

The Mars Exploration Rovers, launched by NASA in 2003 to explore the surface of Mars, are equipped with unique cameras that allow researchers to view stereoscopic images of the surface of Mars.

The two cameras that make up each rover's Pancam

are situated 1.5m above the ground surface, and are separated by 30 cm,

with 1 degree of toe-in. This allows the image pairs to be made into

scientifically useful stereoscopic images, which can be viewed as

stereograms, anaglyphs, or processed into 3D computer images.

The ability to create realistic 3D images from a pair of cameras

at roughly human-height gives researchers increased insight as to the

nature of the landscapes being viewed. In environments without hazy

atmospheres or familiar landmarks, humans rely on stereoscopic clues to

judge distance. Single camera viewpoints are therefore more difficult to

interpret. Multiple camera stereoscopic systems like the Pancam address this problem with unmanned space exploration.

Clinical uses

Stereogram cards and vectographs are used by optometrists, ophthalmologists, orthoptists and vision therapists in the diagnosis and treatment of binocular vision and accommodative disorders.

Mathematical, scientific and engineering uses

Stereopair photographs provided a way for 3-dimensional (3D) visualisations of

aerial photographs;

since about 2000, 3D aerial views are mainly based on digital stereo

imaging technologies. One issue related to stereo images is the amount

of disk space needed to save such files. Indeed, a stereo image usually

requires twice as much space as a normal image. Recently, computer

vision scientists tried to find techniques to attack the visual

redundancy of stereopairs with the aim to define compressed version of

stereopair files. Cartographers generate today stereopairs using computer programs in order to visualise topography in three dimensions. Computerised stereo visualisation applies stereo matching programs.

In biology and chemistry, complex molecular structures are often

rendered in stereopairs. The same technique can also be applied to any

mathematical (or scientific, or engineering) parameter that is a

function of two variables, although in these cases it is more common for

a three-dimensional effect to be created using a 'distorted' mesh or

shading (as if from a distant light source).