State atheism is the incorporation of positive atheism or non-theism into political regimes. It may also refer to large-scale secularization attempts by governments. It is a form of religion-state relationship that is usually ideologically linked to irreligion and the promotion of irreligion to some extent. State atheism may refer to a government's promotion of anti-clericalism, which opposes religious institutional power and influence in all aspects of public and political life, including the involvement of religion in the everyday life of the citizen. In some instances, religious symbols and public practices that were once held by religion were replaced with secularized versions. State atheism can also exist in a politically neutral fashion, in which case it is considered as non-secular.

The majority of communist states followed similar policies from 1917 onwards. The Soviet Union (1922–1991) had a long history of state atheism, whereby those seeking social success generally had to profess atheism and to stay away from houses of worship; this trend became especially militant during the middle of the Stalinist era which lasted from 1929 to 1939. In Eastern Europe, countries like Belarus, Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Russia, and Ukraine experienced strong state atheism policies. East Germany and Czechoslovakia also had similar policies. The Soviet Union attempted to suppress public religious expression over wide areas of its influence, including places such as Central Asia. Either currently or in their past, China, North Korea, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Cuba are or were officially atheist.

In contrast, a secular state purports to be officially neutral in matters of religion, supporting neither religion nor irreligion. In a review of 35 European states in 1980, 5 states were considered 'secular' in the sense of religious neutrality, 9 considered "atheistic", and 21 states considered "religious".

Communist states

A communist state is a state with a form of government which is characterized by the one-party rule or the dominant-party rule of a communist party which professes allegiance to a Leninist or Marxist–Leninist communist ideology as the guiding principle of the state. The founder and primary theorist of Marxism, the 19th-century German thinker Karl Marx, had an ambivalent attitude toward religion, which he primarily viewed as "the opium of the people" which had been used by the ruling classes to give the working classes false hope for millennia, whilst at the same time he also recognized it as a form of protest which the working classes waged against their poor economic conditions. In the Marxist–Leninist interpretation of Marxist theory, developed primarily by Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin, atheism emanates from its dialectical materialism and tries to explain and criticize religion.

Lenin states:

Religion is the opium of the people—this dictum by Marx is the corner-stone of the whole Marxist outlook on religion. Marxism has always regarded all modern religions and churches, and each and every religious organisation, as instruments of bourgeois reaction that serve to defend exploitation and to befuddle the working class.

Although Marx and Lenin were both atheists, several religious communist groups exist, including Christian communists.

Julian Baggini devotes a chapter of his book Atheism: A Very Short Introduction to a discussion about 20th-century political systems, including communism and political repression in the Soviet Union. Baggini argues that "Soviet communism, with its active oppression of religion, is a distortion of original Marxist communism, which did not advocate oppression of the religious." Baggini goes on to argue that "Fundamentalism is a danger in any belief system" and that "Atheism's most authentic political expression... takes the form of state secularism, not state atheism."

Soviet Union

State atheism (gosateizm, a syllabic abbreviation of "state" [gosudarstvo] and "atheism" [ateizm]) was a major goal of the official Soviet ideology. This phenomenon, which lasted for seven decades, was new in world history. The Communist Party engaged in diverse activities such as destroying places of worship, executing religious leaders, flooding schools and media with anti-religious propaganda, and propagated "scientific atheism". It sought to make religion disappear by various means. Thus, the USSR became the first state to have as one objective of its official ideology the elimination of the existing religion, and the prevention of the future implanting of religious belief, with the goal of establishing state atheism (gosateizm).

After the Russian Civil War, the state used its resources to stop the implanting of religious beliefs in nonbelievers and remove "prerevolutionary remnants" which still existed. The Bolsheviks were particularly hostile toward the Russian Orthodox Church (which supported the White Movement during the Russian Civil War) and saw it as a supporter of Tsarist autocracy. During the collectivization of the land, Orthodox priests distributed pamphlets declaring that the Soviet regime was the Antichrist coming to place "the Devil's mark" on the peasants, and encouraged them to resist the government. Political repression in the Soviet Union was widespread and while religious persecution was applied to numerous religions, the regime's anti-religious campaigns were often directed against specific religions based on state interests. The attitude in the Soviet Union toward religion varied from persecution of some religions to not outlawing others.

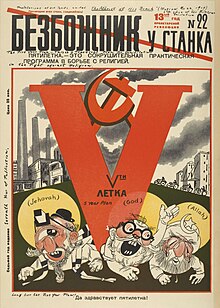

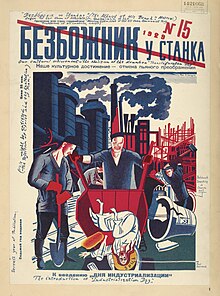

From the late 1920s to the late 1930s, such organizations as the League of Militant Atheists ridiculed all religions and harassed believers. The league was a "nominally independent organization established by the Communist Party to promote atheism". It published its own newspaper, and journals, sponsored lectures, and organized demonstrations that lampooned religion and promoted atheism. Anti-religious and atheistic propaganda was implemented into every portion of soviet life from schools to the media and even on to substituting rituals to replace religious ones. Though Lenin originally introduced the Gregorian calendar to the Soviets, subsequent efforts to reorganise the week to improve worker productivity saw the introduction of the Soviet calendar, which had the side-effect that a "holiday will seldom fall on Sunday".

Within about a year of the revolution, the state expropriated all church property, including the churches themselves, and in the period from 1922 to 1926, 28 Russian Orthodox bishops and more than 1,200 priests were killed (a much greater number was subjected to persecution). Most seminaries were closed, and publication of religious writing was banned. A meeting of the Antireligious Commission of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) that occurred on 23 May 1929 estimated the portion of believers in the USSR at 80 percent, though this percentage may be understated to prove the successfulness of the struggle with religion. The Russian Orthodox Church, which had 54,000 parishes before World War I, was reduced to 500 by 1940. Overall, by that same year 90 percent of the churches, synagogues, and mosques that had been operating in 1917 were either forcibly closed, converted, or destroyed.

Since the Soviet era, Russia, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Belarus, Moldova, Georgia, Ukraine and Lithuania have diverse religious affiliations. Professor Niels Christian Nielsen of philosophy and religious thought of Rice University has written that the post-Soviet population in areas which were formerly predominantly Orthodox are now "nearly illiterate regarding religion", almost completely lacking the intellectual or philosophical aspects of their faith and having almost no knowledge of other faiths.

In 1928, the Jewish Autonomous Oblast was established by Joseph Stalin, acting on an idea proposed by Lenin in order to give the Jewish population in Russia more personal autonomy, as reparation for antisemitism in the Russian Empire. Along with granting Jewish autonomy, Stalin also allowed Sharia law in the majority-Islamic countries of the Soviet Union. "The Soviet Government considers that the Sharia, as common law, is as fully authorized as that of any other of the peoples inhabiting Russia." (Statement by Stalin during the Congress of the Peoples of Dagestan, an autonomous republic in Russia). Art. 135 of the 1936 constitution of the Soviet Union protects individuals from religious discrimination.

Albania

In 1967 Enver Hoxha, the head of state of Albania, declared Albania to be the "first atheist state of the world" even though the Soviet Union under Lenin had already been a de facto atheist state. Marxist–Leninist authorities in Albania claimed that religion was foreign to Albania and used this to justify their policy of state atheism and suppression of religion. This nationalism was also used to justify the communist stance of state atheism from 1967 to 1991. The Agrarian Reform Law of August 1945 nationalized most property of religious institutions, including the estates of mosques, monasteries, orders, and dioceses. Many clergy and believers were tried and some were executed. All foreign Roman Catholic priests, monks, and nuns were expelled in 1946.

Religious communities or branches that had their headquarters outside the country, such as the Jesuit and Franciscan orders, were henceforth ordered to terminate their activities in Albania. Religious institutions were forbidden to have anything to do with the education of the young, because that had been made the exclusive province of the state. All religious communities were prohibited from owning real estate and operating philanthropic and welfare institutions and hospitals.

Although there were tactical variations in Enver Hoxha's approach to each of the major denominations, his overarching objective was the eventual destruction of all organized religion in Albania. Between 1945 and 1953, the number of priests was reduced drastically and the number of Roman Catholic churches was decreased from 253 to 100, and all Catholics were stigmatized as fascists.

The campaign against religion peaked in the 1960s. Beginning in February 1967 the Albanian authorities launched a campaign to eliminate religious life in Albania. Despite complaints, even by APL members, all churches, mosques, monasteries, and other religious institutions were either closed down or converted into warehouses, gymnasiums, or workshops by the end of 1967. By May 1967, religious institutions had been forced to relinquish all 2,169 churches, mosques, cloisters, and shrines in Albania, many of which were converted into cultural centers for young people. As the literary monthly Nendori reported the event, the youth had thus "created the first atheist nation in the world."

Clerics were publicly vilified and humiliated, their vestments were taken and desecrated. More than 200 clerics of various faiths were imprisoned, others were forced to seek work in either industry or agriculture, and some were executed or starved to death. The cloister of the Franciscan order in Shkodër was set on fire, which resulted in the death of four elderly monks.

Article 37 of the Albanian Constitution of 1976 stipulated, "The state recognizes no religion, and supports atheistic propaganda in order to implant a scientific materialistic world outlook in people." The penal code of 1977 imposed prison sentences of three to ten years for "religious propaganda and the production, distribution, or storage of religious literature", which meant that individuals caught with Bibles, Qurans, icons, or other religious objects faced long prison sentences. A new decree that in effect targeted Albanians with Muslim and Christian names, stipulating that citizens whose names did not conform to "the political, ideological, or moral standards of the state" were to change them. It was also decreed that towns and villages with religious names must be renamed. Hoxha's brutal antireligious campaign succeeded in eradicating formal worship, but some Albanians continued to practice their faith clandestinely, risking severe punishment.

Parents were afraid to pass on their faith, for fear that their children would tell others. Officials tried to entrap practicing Christians and Muslims during religious fasts, such as Lent and Ramadan, by distributing dairy products and other forbidden foods in school and at work, and then publicly denouncing those who refused the food. Those clergy who conducted secret services were incarcerated. Catholic priest Shtjefen Kurti was executed for secretly baptizing a child in Shkodër in 1972.

The article was interpreted by Danes as violating The United Nations Charter (chapter 9, article 55) which declares that religious freedom is an inalienable human right. The first time that the question came before the United Nations' Commission on Human Rights at Geneva was as late as 7 March 1983. A delegation from Denmark got its protest over Albania's violation of religious liberty placed on the agenda of the thirty-ninth meeting of the commission, item 25, reading, "Implementation of the Declaration on the Elimination of all Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination based on Religion or Belief.", and on 20 July 1984 a member of the Danish Parliament inserted an article into one of Denmark's major newspapers protesting the violation of religious freedom in Albania.

The 1998 Constitution of Albania defined the country as a parliamentary republic, and established personal and political rights and freedoms, including protection against coercion in matters of religious belief. Albania is a member state of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, and the 2011 census found that 58.79% of Albanians adhere to Islam, making it the largest religion in the country. The majority of Albanian Muslims are secular Sunnis along with a significant Bektashi Shia minority. Christianity is practiced by 16.99% of the population, making it the 2nd largest religion in the country. The remaining population is either irreligious or belongs to other religious groups. In 2011, Albania's population was estimated to be 56.7% Muslim, 10% Roman Catholic, 6.8% Orthodox, 2.5% atheist, 2.1% Bektashi (a Sufi order), 5.7% other, 16.2% unspecified. Today, Gallup Global Reports 2010 shows that religion plays a role in the lives of 39% of Albanians, and Albania is ranked the thirteenth least religious country in the world. The U.S. state department reports that in 2013, "There were no reports of societal abuses or discrimination based on religious affiliation, belief, or practice."

Cambodia

The Khmer Rouge actively persecuted Buddhists during their reign from 1975 to 1979. Buddhist institutions and temples were destroyed and Buddhist monks and teachers were killed in large numbers. A third of the nation's monasteries were destroyed along with numerous holy texts and items of high artistic quality. 25,000 Buddhist monks were massacred by the regime, which was officially an atheist state. The persecution was undertaken because Pol Pot believed that Buddhism was "a decadent affectation". He sought to eliminate Buddhism's 1,500-year-old mark on Cambodia.

Under the Khmer Rouge, all religious practices were banned. According to Ben Kiernan, "the Khmer Rouge repressed Islam, Christianity, and Buddhism, but its fiercest extermination campaign was directed against the ethnic Cham Muslim minority."

China

China has adopted a policy of official state atheism. Art. 36 of the Chinese constitution guarantees freedom of religion but limits the right to practice religion to state sanctioned organisations. The government has promoted atheism throughout the country. In April 2016, the General Secretary, Xi Jinping, stated that members of the Chinese Communist Party must be "unyielding Marxist atheists" while in the same month, a government-sanctioned demolition work crew drove a bulldozer over two Chinese Christians who protested the demolition of their church by refusing to step aside.

Traditionally, a large segment of the Chinese population took part in Chinese folk religions and Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism had played a significant role in the everyday lives of ordinary people. After the 1949 Chinese Revolution, China began a period of rule by the Chinese Communist Party. For much of its early history, that government maintained under Marxist thought that religion would ultimately disappear, and characterized it as emblematic of feudalism and foreign colonialism.

During the Cultural Revolution, student vigilantes known as Red Guards converted religious buildings for secular use or destroyed them. This attitude, however, relaxed considerably in the late 1970s, with the reform and opening up period. The 1978 Constitution of the People's Republic of China guaranteed freedom of religion with a number of restrictions. Since then, there has been a massive program to rebuild Buddhist and Taoist temples that were destroyed in the Cultural Revolution.

The Communist Party has said that religious belief and membership are incompatible. However, the state is not allowed to force ordinary citizens to become atheists. China's five officially sanctioned religious organizations are the Buddhist Association of China, Chinese Taoist Association, Islamic Association of China, Three-Self Patriotic Movement and Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association. These groups are afforded a degree of protection, but are subject to restrictions and controls under the State Administration for Religious Affairs. Unregistered religious groups face varying degrees of harassment. The constitution permits what is called "normal religious activities," so long as they do not involve the use of religion to "engage in activities that disrupt social order, impair the health of citizens or interfere with the educational system of the state. Religious organizations and religious affairs are not subject to any foreign dominance."

Article 36 of the Constitution of the People's Republic of China of 1982 specifies that:

Citizens of the People's Republic of China enjoy freedom of religious belief. No state organ, public organization or individual may compel citizens to believe in, or not to believe in, any religion; nor may they discriminate against citizens who believe in, or do not believe in, any religion. The state protects normal religious activities. No one may make use of religion to engage in activities that disrupt public order, impair the health of citizens or interfere with the educational system of the state. Religious bodies and religious affairs are not subject to any foreign domination.

Most people report no organized religious affiliation; however, people with a belief in folk traditions and spiritual beliefs, such as ancestor veneration and feng shui, along with informal ties to local temples and unofficial house churches number in the hundreds of millions. The United States Department of State, in its annual report on International Religious Freedom, provides statistics about organized religions. In 2007, it reported the following (citing the Government's 1997 report on Religious Freedom and 2005 White Paper on religion):

- Buddhists 8%.

- Taoists, unknown as a percentage partly because it is fused along with Confucianism and Buddhism.

- Muslims, 1%, with more than 20,000 Imams. Other estimates state at least 1%.

- Christians, Protestants at least 2%. Catholics, about 1%.

Statistics relating to Buddhism and religious Taoism are to some degree incomparable with statistics for Islam and Christianity. This is due to the traditional Chinese belief system which blends Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, so that a person who follows a traditional belief system would not necessarily identify him- or herself as exclusively Buddhist or Taoist, despite attending Buddhist or Taoist places of worship. According to Peter Ng, Professor of the Department of Religion at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, as of 2002, 95% of Chinese were religious in some way if religion is considered to include traditional folk practices such as burning incense for gods or ancestors at life-cycle or seasonal festivals, fortune telling and related customary practices.

The U.S. State Department has designated China as a "country of particular concern" since 1999, in part due to the scenario of Uighur Muslims and Tibetan Buddhists. Freedom House classifies Tibet and Xinjiang as regions of particular repression of religion, due to concerns of separatist activity. Heiner Bielefeldt, the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, says that China's actions against the Uighurs are "a major problem". The Chinese government has protested the report, saying the country has "ample" religious freedom.

Cuba

Until 1992, Cuba was officially an atheist state.

In August 1960, several bishops signed a joint pastoral letter condemning communism and declaring it incompatible with Catholicism, and calling on Catholics to reject it. Fidel Castro gave a four-hour long speech the next day, condemning priests who serve "great wealth" and using fears of Falangist influence in order to attack Spanish-born priests, declaring "There is no doubt that Franco has a sizeable group of fascist priests in Cuba."

Originally more tolerant of religion, the Cuban government began arresting many believers and shutting down religious schools after the Bay of Pigs Invasion. Its prisons were being filled with clergy since the 1960s. In 1961, the Cuban government confiscated Catholic schools, including the Jesuit school that Fidel Castro had attended. In 1965 it exiled two hundred priests.

In 1976, the Constitution of Cuba added a clause stating that the "socialist state...bases its activity on, and educates the people in, the scientific materialist concept of the universe". In 1992, the dissolution of the Soviet Union led the country to declare itself a secular state. Pope John Paul II contributed to the Cuban thaw when he paid a historic visit to the island in 1998 and criticized the US embargo. Pope Benedict XVI visited Cuba in 2012 and Pope Francis visited Cuba in 2015. The Cuban government continued hostile actions against religious groups; in 2015 alone, the Castro regime ordered the closure or demolition of over 100 Pentecostal, Methodist, and Baptist parishes, according to a report from Christian Solidarity Worldwide.

East Germany

Though Article 39 of the GDR constitution of 1968 guarantees religious freedom, state policy was oriented towards the promotion of atheism. Eastern Germany practiced heavy secularization. The German Democratic Republic (GDR) generated antireligous regulations and promoted atheism for decades which impacted the growth of citizens affiliating with no religion from 7.6% in 1950 to 60% in 1986. It was in the 1950s that scientific atheism became official state policy when Soviet authorities were setting up a communist government. As of 2012 the area of the former German Democratic Republic was the least religious region in the world.

North Korea

The North Korean constitution states that freedom of religion is permitted. Conversely, the North Korean government's Juche ideology has been described as "state-sanctioned atheism" and atheism is the government's official position. According to a 2018 CIA report, free religious activities almost no longer exist, with government-sponsored groups to delude. The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom stated that assessing the situation in North Korea is challenging, but that reports that DPRK officials repress religious activities have surfaced, including about the government forming and controlling religious organizations to restrict religious activities. Human Rights Overview reported in 2004 that North Korea remains one of the most repressive governments, with isolation and disregard for international law making monitoring almost impossible. After 1,500 churches were destroyed during the rule of Kim Il-sung from 1948 to 1994, three churches were built in Pyongyang. Foreign residents regularly attending services at these churches have reported that services there are staged for their benefit.

The North Korean government promotes the cult of personality of Kim Jong-il and Kim Il-sung, described as a political religion, as well as the Juche ideology, based on Korean ultranationalism, which calls on people to "avoid spiritual deference to outside influences", which was interpreted as including religion originating outside of Korea.

North Korea has been designated a "country of particular concern" by the U.S. State Department since 2001 due to its religious freedom violations. Cardinal Nicolas Cheong Jin-suk has said that, "There's no knowledge of priests surviving persecution that came in the late forties, when 166 priests and religious were killed or kidnapped," which includes the Roman Catholic bishop of Pyongyang, Francis Hong Yong-ho. In November 2013 it was reported that the repression against religious people led to the public execution of 80 people, some of them for possessing Bibles.

There are five Christian churches in Pyongyang, three Protestant, one Eastern Orthodox, and one Catholic. President Kim Il-sung and his mother were frequent patrons of Chilgol Church, one of the Protestant churches, and that church can be visited on tour. Christian institutions are state regulated by the Korean Christian Federation. The governing party front of North Korea is made mostly of Cheondoist parties, although the Worker's Party of Korea dominates it. There are around 300 active Cheondist churches in the DPRK.

Mongolia

The Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party (MPRP) propagated atheism until the 1960s. In the Mongolian People's Republic, after it was invaded by Japanese troops in 1936, the Soviet Union deployed its troops there in 1937, undertaking an offensive against the Buddhist religion. Parallel with this, a Soviet-style purge was launched in the People's Revolutionary Party and the Mongolian army. The Mongol leader at that time was Khorloogiin Choibalsan, a follower of Joseph Stalin, who emulated many of the policies that Stalin had previously implemented in the Soviet Union. The purge virtually succeeded in eliminating Tibetan Buddhism and cost an estimated thirty to thirty-five thousand lives.

Vietnam

Officially, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam is an atheist state as declared by its communist government. Art. 24 of the constitution of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam recognizes religious freedom.

Non-Communist states

Revolutionary Mexico

Articles 3, 5, 24, 27, and 130 of the Mexican Constitution of 1917 as originally enacted included anticlerical provisions and restricted religious freedoms. The Articles were initially seldom enforced until President Plutarco Elías Calles, who sought to enact the separation of church and state established in the Constitution of 1917, took office in 1924. Calles' Mexico has been characterized as an atheist state and his program as aiming to eradicate religious practices in Mexico during the 20th century.

There was an expulsion of foreign clergy and expropriation of Church properties. Article 27 prohibited any future acquisition of such property by churches, and prohibited religious corporations and ministers from establishing or directing primary schools. The Constitution of 1917 also forbade the existence of monastic orders (Article 5) and religious activities outside of church buildings (which became government property), and mandated that such religious activities would be overseen by government (Article 24).

On 14 June 1926, President Calles enacted anticlerical legislation known formally as The Law Reforming the Penal Code and unofficially as Calles Law. His anti-Catholic actions included outlawing religious orders, depriving the Church of property rights and depriving the clergy of civil liberties, including their right to a trial by jury in cases involving anti-clerical laws and the right to vote. Catholic antipathy towards Calles was enhanced because of his vocal anti-Catholicism.

Due to the strict enforcement of anticlerical laws, people in strongly Catholic states, especially Jalisco, Zacatecas, Guanajuato, Colima and Michoacán, began to oppose him, and this opposition led to the Cristero War from 1926 to 1929, which was characterized by atrocities on both sides. Some Cristeros applied terrorist tactics, including the torture and killing of public school teachers, while the Mexican government persecuted the clergy, killing suspected Cristeros and supporters and often retaliating against innocent individuals.

A truce was negotiated with the assistance of U.S. Ambassador Dwight Whitney Morrow. Calles, however, in violation of its terms did not abide by the truce and he had approximately 500 Cristero leaders and 5,000 other Cristeros shot, frequently in their homes in front of their spouses and children. Particularly offensive to Catholics after the supposed truce was Calles' insistence on a state monopoly on education, suppressing Catholic education and introducing socialist education in its place: "We must enter and take possession of the mind of childhood, the mind of youth." Persecutions continued as Calles maintained control under the Maximato and did not relent until 1940, when President Manuel Ávila Camacho took office. Attempts to eliminate religious education became more pronounced in 1934 through an amendment of Article 3 of the Mexican Constitution, which strived to eliminate religion by mandating "socialist education", which "in addition to removing all religious doctrine" would "combat fanaticism and prejudices", "build[ing] in the youth a rational and exact concept of the universe and of social life". In 1946, socialist education provisions were removed from the constitution and new laws promoted secular education. Between 1926 and 1934 at least 40 priests were killed. Where there were 4,500 priests operating within the country before the War, in 1934 there were only 334 priests licensed by the government to serve fifteen million people, the rest having been killed, exiled or not obtaining licenses. In 1935, 17 states had no registered priests.

Revolutionary France

The French Revolution initially began with attacks on Church corruption and the wealth of the higher clergy, an action with which even many Christians could identify, since the Gallican Church held a dominant role in pre-revolutionary France. During a two-year period known as the Reign of Terror, the episodes of anti-clericalism grew more violent than any in modern European history. The new revolutionary authorities suppressed the Church, abolished the Catholic monarchy, nationalized Church property, exiled 30,000 priests, and killed hundreds more. In October 1793, the Christian calendar was replaced with one reckoned from the date of the Revolution, and Festivals of Liberty, Reason, and the Supreme Being were scheduled. New forms of moral religion emerged, including the deistic Cult of the Supreme Being and the atheistic Cult of Reason, with the revolutionary government briefly mandating observance of the former in April 1794.

Human rights

Antireligious states, including atheist states, have been at odds with human rights law. Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is designed to protect freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. In 1993, the UN's human rights committee declared that article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights "protects theistic, non-theistic and atheistic beliefs, as well as the right not to profess any religion or belief." The committee further stated that "the freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief necessarily entails the freedom to choose a religion or belief, including the right to replace one's current religion or belief with another or to adopt atheistic views." Signatories to the convention are barred from "the use of threat of physical force or penal sanctions to compel believers or non-believers" to recant their beliefs or convert. Despite this, as of 2009 minority religions were still being persecuted in many parts of the world.

Theodore Roosevelt condemned the Kishinev pogrom in 1903, establishing a history of U.S. presidents commenting on the internal religious liberty of foreign countries. In Franklin D. Roosevelt's 1941 State of the Union address, he outlined Four Freedoms, including Freedom of worship, that would be foundation for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and future U.S. diplomatic efforts. Jimmy Carter asked Deng Xiaoping to improve religious freedom in China, and Ronald Reagan told US Embassy staff in Moscow to help Jews harassed by the Soviet authorities. Bill Clinton established the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom with the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998, in order to use diplomacy to promote religious liberty in repressive states. Countries like Albania had anti-religious policies, while also promoting atheism, that impacted their religious rights.