Naturalis Historia, 1669 edition, title page. The title at the top reads: "Volume I of the Natural History of Gaius Plinius Secundus". | |

| Author | Pliny the Elder |

|---|---|

| Country | Ancient Rome |

| Subject | Natural history, ethnography, art, sculpture, mining, mineralogy |

| Genre | Encyclopaedia, popular science |

The Natural History (Latin: Naturalis historia) is a work by Pliny the Elder. The largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day, the Natural History compiles information gleaned from other ancient authors. Despite the work's title, its subject area is not limited to what is today understood by natural history; Pliny himself defines his scope as "the natural world, or life". It is encyclopedic in scope, but its structure is not like that of a modern encyclopedia. It is the only work by Pliny to have survived, and the last that he published. He published the first 10 books in AD 77, but had not made a final revision of the remainder at the time of his death during the AD 79 eruption of Vesuvius. The rest was published posthumously by Pliny's nephew, Pliny the Younger.

The work is divided into 37 books, organised into 10 volumes. These cover topics including astronomy, mathematics, geography, ethnography, anthropology, human physiology, zoology, botany, agriculture, horticulture, pharmacology, mining, mineralogy, sculpture, art, and precious stones.

Pliny's Natural History became a model for later encyclopedias and scholarly works as a result of its breadth of subject matter, its referencing of original authors, and its index.

Overview

Pliny's Natural History was written alongside other substantial works (which have since been lost). Pliny (AD 23–79) combined his scholarly activities with a busy career as an imperial administrator for the emperor Vespasian. Much of his writing was done at night; daytime hours were spent working for the emperor, as he explains in the dedicatory preface addressed to Vespasian's elder son, the future emperor Titus, with whom he had served in the army (and to whom the work is dedicated). As for the nocturnal hours spent writing, these were seen not as a loss of sleep but as an addition to life, for as he states in the preface, Vita vigilia est, "to be alive is to be watchful", in a military metaphor of a sentry keeping watch in the night. Pliny claims to be the only Roman ever to have undertaken such a work, in his prayer for the blessing of the universal mother:

Hail to thee, Nature, thou parent of all things! and do thou deign to show thy favour unto me, who, alone of all the citizens of Rome, have, in thy every department, thus made known thy praise.

The Natural History is encyclopaedic in scope, but its format is unlike a modern encyclopaedia. However, it does have structure: Pliny uses Aristotle's division of nature (animal, vegetable, mineral) to recreate the natural world in literary form. Rather than presenting compartmentalised, stand-alone entries arranged alphabetically, Pliny's ordered natural landscape is a coherent whole, offering the reader a guided tour: "a brief excursion under our direction among the whole of the works of nature ..." The work is unified but varied: "My subject is the world of nature ... or in other words, life," he tells Titus.

Nature for Pliny was divine, a pantheistic concept inspired by the Stoic philosophy, which underlies much of his thought, but the deity in question was a goddess whose main purpose was to serve the human race: "nature, that is life" is human life in a natural landscape. After an initial survey of cosmology and geography, Pliny starts his treatment of animals with the human race, "for whose sake great Nature appears to have created all other things". This teleological view of nature was common in antiquity and is crucial to the understanding of the Natural History. The components of nature are not just described in and for themselves, but also with a view to their role in human life. Pliny devotes a number of the books to plants, with a focus on their medicinal value; the books on minerals include descriptions of their uses in architecture, sculpture, art, and jewellery. Pliny's premise is distinct from modern ecological theories, reflecting the prevailing sentiment of his time.

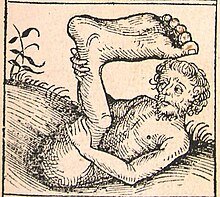

Pliny's work frequently reflects Rome's imperial expansion, which brought new and exciting things to the capital: exotic eastern spices, strange animals to be put on display or herded into the arena, even the alleged phoenix sent to the emperor Claudius in AD 47 – although, as Pliny admits, this was generally acknowledged to be a fake. Pliny repeated Aristotle's maxim that Africa was always producing something new. Nature's variety and versatility were claimed to be infinite: "When I have observed nature she has always induced me to deem no statement about her incredible." This led Pliny to recount rumours of strange peoples on the edges of the world. These monstrous races – the Cynocephali or Dog-Heads, the Sciapodae, whose single foot could act as a sunshade, the mouthless Astomi, who lived on scents – were not strictly new. They had been mentioned in the fifth century BC by Greek historian Herodotus (whose history was a broad mixture of myths, legends, and facts), but Pliny made them better known.

"As full of variety as nature itself", stated Pliny's nephew, Pliny the Younger, and this verdict largely explains the appeal of the Natural History since Pliny's death in the Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79. Pliny had gone to investigate the strange cloud – "shaped like an umbrella pine", according to his nephew – rising from the mountain.

The Natural History was one of the first ancient European texts to be printed, in Venice in 1469. Philemon Holland's English translation of 1601 has influenced literature ever since.

Structure

The Natural History consists of 37 books. Pliny devised a summarium, or list of contents, at the beginning of the work that was later interpreted by modern printers as a table of contents. The table below is a summary based on modern names for topics.

| Volume | Books | Contents |

|---|---|---|

| I | 1 | Preface and list of contents, lists of authorities |

| 2 | Astronomy, meteorology | |

| II | 3–6 | Geography and ethnography |

| 7 | Anthropology and human physiology | |

| III | 8–11 | Zoology, including mammals, snakes, marine animals, birds, insects |

| IV–VII | 12–27 | Botany, including agriculture, horticulture, especially of the vine and olive, medicine |

| VIII | 28–32 | Pharmacology, magic, water, aquatic life |

| IX–X | 33–37 | Mining and mineralogy, especially as applied to life and art, work in gold and silver, statuary in bronze, art, modelling, sculpture in marble, precious stones and gems |

Production

Purpose

Pliny's purpose in writing the Natural History was to cover all learning and art so far as they are connected with nature or draw their materials from nature. He says:

My subject is a barren one – the world of nature, or in other words life; and that subject in its least elevated department, and employing either rustic terms or foreign, nay barbarian words that actually have to be introduced with an apology. Moreover, the path is not a beaten highway of authorship, nor one in which the mind is eager to range: there is not one of us who has made the same venture, nor yet one among the Greeks who has tackled single-handed all departments of the subject.

Sources

Pliny studied the original authorities on each subject and took care to make excerpts from their pages. His indices auctorum sometimes list the authorities he actually consulted, though not exhaustively; in other cases, they cover the principal writers on the subject, whose names are borrowed second-hand from his immediate authorities. He acknowledges his obligations to his predecessors: "To own up to those who were the means of one's own achievements."

In the preface, the author claims to have stated 20,000 facts gathered from some 2,000 books and from 100 select authors. The extant lists of his authorities cover more than 400, including 146 Roman and 327 Greek and other sources of information. The lists generally follow the order of the subject matter of each book. This has been shown in Heinrich Brunn's Disputatio (Bonn, 1856).

One of Pliny's authorities is Marcus Terentius Varro. In the geographical books, Varro is supplemented by the topographical commentaries of Agrippa, which were completed by the emperor Augustus; for his zoology, he relies largely on Aristotle and on Juba, the scholarly Mauretanian king, studiorum claritate memorabilior quam regno (v. 16). Juba is one of his principal guides in botany; Theophrastus is also named in his Indices, and Pliny had translated Theophrastus's Greek into Latin. Another work by Theophrastus, On Stones was cited as a source on ores and minerals. Pliny strove to use all the Greek histories available to him, such as Herodotus and Thucydides, as well as the Bibliotheca Historica of Diodorus Siculus.

Working method

His nephew, Pliny the Younger, described the method that Pliny used to write the Natural History:

Does it surprise you that a busy man found time to finish so many volumes, many of which deal with such minute details?... He used to begin to study at night on the Festival of Vulcan, not for luck but from his love of study, long before dawn; in winter he would commence at the seventh hour... He could sleep at call, and it would come upon him and leave him in the middle of his work. Before daybreak he would go to Vespasian – for he too was a night-worker – and then set about his official duties. On his return home he would again give to study any time that he had free. Often in summer after taking a meal, which with him, as in the old days, was always a simple and light one, he would lie in the sun if he had any time to spare, and a book would be read aloud, from which he would take notes and extracts.

Pliny the Younger told the following anecdote illustrating his uncle's enthusiasm for study:

After dinner a book would be read aloud, and he would take notes in a cursory way. I remember that one of his friends, when the reader pronounced a word wrongly, checked him and made him read it again, and my uncle said to him, "Did you not catch the meaning?" When his friend said "yes," he remarked, "Why then did you make him turn back? We have lost more than ten lines through your interruption." So jealous was he of every moment lost.

Style

Pliny's writing style emulates that of Seneca. It aims less at clarity and vividness than at epigrammatic point. It contains many antitheses, questions, exclamations, tropes, metaphors, and other mannerisms of the Silver Age. His sentence structure is often loose and straggling. There is heavy use of the ablative absolute, and ablative phrases are often appended in a kind of vague "apposition" to express the author's own opinion of an immediately previous statement, e.g.,

dixit (Apelles) ... uno se praestare, quod manum de tabula sciret tollere, memorabili praecepto nocere saepe nimiam diligentiam.

This might be translated

In one thing Apelles stood out, namely, knowing when he had put enough work into a painting, a salutary warning that too much effort can be counterproductive.

Everything from "a salutary warning" onwards represents the ablative absolute phrase starting with "memorabili praecepto".

Publication history

First publication

Pliny wrote the first ten books in AD 77, and was engaged on revising the rest during the two remaining years of his life. The work was probably published with little revision by the author's nephew Pliny the Younger, who, when telling the story of a tame dolphin and describing the floating islands of the Vadimonian Lake thirty years later, has apparently forgotten that both are to be found in his uncle's work. He describes the Naturalis Historia as a Naturae historia and characterises it as a "work that is learned and full of matter, and as varied as nature herself."

The absence of the author's final revision may explain many errors, including why the text is as John Healy writes "disjointed, discontinuous and not in a logical order"; and as early as 1350, Petrarch complained about the corrupt state of the text, referring to copying errors made between the ninth and eleventh centuries.

Manuscripts

About the middle of the 3rd century, an abstract of the geographical portions of Pliny's work was produced by Solinus. Early in the 8th century, Bede, who admired Pliny's work, had access to a partial manuscript which he used in his "De Rerum Natura", especially the sections on meteorology and gems. However, Bede updated and corrected Pliny on the tides.

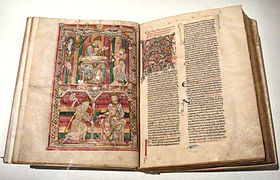

There are about 200 extant manuscripts, but the best of the more ancient manuscripts, that at Bamberg State Library, contains only books XXXII–XXXVII. In 1141 Robert of Cricklade wrote the Defloratio Historiae Naturalis Plinii Secundi consisting of nine books of selections taken from an ancient manuscript.

Printed copies

The work was one of the first classical manuscripts to be printed, at Venice in 1469 by Johann and Wendelin of Speyer, but J.F. Healy described the translation as "distinctly imperfect". A copy printed in 1472 by Nicolas Jenson of Venice is held in the library at Wells Cathedral.

Translations

Philemon Holland made an influential translation of much of the work into English in 1601. John Bostock and H. T. Riley made a complete translation in 1855.

Topics

The Natural History is generally divided into the organic plants and animals and the inorganic matter, although there are frequent digressions in each section. The encyclopedia also notes the uses made of all of these by the Romans. Its description of metals and minerals is valued for its detail in the history of science, being the most extensive compilation still available from the ancient world.

Book I serves as Pliny's preface, explaining his approach and providing a table of contents.

Astronomy

The first topic covered is Astronomy, in Book II. Pliny starts with the known universe, roundly criticising attempts at cosmology as madness, including the view that there are countless other worlds than the Earth. He concurs with the four (Aristotelian) elements, fire, earth, air and water, and records the seven "planets" including the sun and moon. The earth is a sphere, suspended in the middle of space. He considers it a weakness to try to find the shape and form of God, or to suppose that such a being would care about human affairs. He mentions eclipses, but considers Hipparchus's almanac grandiose for seeming to know how Nature works. He cites Posidonius's estimate that the moon is 230,000 miles away. He describes comets, noting that only Aristotle has recorded seeing more than one at once.

Book II continues with natural meteorological events lower in the sky, including the winds, weather, whirlwinds, lightning, and rainbows. He returns to astronomical facts such as the effect of longitude on time of sunrise and sunset, the variation of the sun's elevation with latitude (affecting time-telling by sundials), and the variation of day length with latitude.

Geography

In Books III to VI, Pliny moves to the Earth itself. In Book III he covers the geography of the Iberian peninsula and Italy; Book IV covers Europe including Britain; Book V looks at Africa and Asia, while Book VI looks eastwards to the Black Sea, India and the Far East.

Anthropology

Book VII discusses the human race, covering anthropology and ethnography, aspects of human physiology and assorted matters such as the greatness of Julius Caesar, outstanding people such as Hippocrates and Asclepiades, happiness and fortune.

Zoology

Zoology is discussed in Books VIII to XI. The encyclopedia mentions different sources of purple dye, particularly the murex snail, the highly prized source of Tyrian purple. It describes the elephant and hippopotamus in detail, as well as the value and origin of the pearl and the invention of fish farming and oyster farming. The keeping of aquariums was a popular pastime of the rich, and Pliny provides anecdotes of the problems of owners becoming too closely attached to their fish.

Pliny correctly identifies the origin of amber as the fossilised resin of pine trees. Evidence cited includes the fact that some samples exhibit encapsulated insects, a feature readily explained by the presence of a viscous resin. Pliny refers to the way in which it exerts a charge when rubbed, a property well known to Theophrastus. He devotes considerable space to bees, which he admires for their industry, organisation, and honey, discussing the significance of the queen bee and the use of smoke by beekeepers at the hive to collect honeycomb. He praises the song of the nightingale.

Botany

Botany is handled in Books XII to XVIII, with Theophrastus as one of Pliny's sources. The manufacture of papyrus and the various grades of papyrus available to Romans are described. Different types of trees and the properties of their wood are explained in Books XII to XIII. The vine, viticulture and varieties of grape are discussed in Book XIV, while Book XV covers the olive tree in detail, followed by other trees including the apple and pear, fig, cherry, myrtle and laurel, among others.

Pliny gives special attention to spices, such as pepper, ginger, and cane sugar. He mentions different varieties of pepper, whose values are comparable with that of gold and silver, while sugar is noted only for its medicinal value.

He is critical of perfumes: "Perfumes are the most pointless of luxuries, for pearls and jewels are at least passed on to one's heirs, and clothes last for a time, but perfumes lose their fragrance and perish as soon as they are used." He gives a summary of their ingredients, such as attar of roses, which he says is the most widely used base. Other substances added include myrrh, cinnamon, and balsam gum.

Drugs, medicine and magic

A major section of the Natural History, Books XX to XXIX, discusses matters related to medicine, especially plants that yield useful drugs. Pliny lists over 900 drugs, compared to 600 in Dioscorides's De Materia Medica, 550 in Theophrastus, and 650 in Galen. The poppy and opium are mentioned; Pliny notes that opium induces sleep and can be fatal. Diseases and their treatment are covered in book XXVI.

Pliny addresses magic in Book XXX. He is critical of the Magi, attacking astrology, and suggesting that magic originated in medicine, creeping in by pretending to offer health. He names Zoroaster of Ancient Persia as the source of magical ideas. He states that Pythagoras, Empedocles, Democritus and Plato all travelled abroad to learn magic, remarking that it was surprising anyone accepted the doctrines they brought back, and that medicine (of Hippocrates) and magic (of Democritus) should have flourished simultaneously at the time of the Peloponnesian War.

Agriculture

The methods used to cultivate crops are described in Book XVIII. He praises Cato the Elder and his work De Agri Cultura, which he uses as a primary source. Pliny's work includes discussion of all known cultivated crops and vegetables, as well as herbs and remedies derived from them. He describes machines used in cultivation and processing the crops. For example, he describes a simple mechanical reaper that cut the ears of wheat and barley without the straw and was pushed by oxen (Book XVIII, chapter 72). It is depicted on a bas-relief found at Trier from the later Roman period. He also describes how grain is ground using a pestle, a hand-mill, or a mill driven by water wheels, as found in Roman water mills across the Empire.

Metallurgy

Pliny extensively discusses metals starting with gold and silver (Book XXXIII), and then the base metals copper, mercury, lead, tin and iron, as well as their many alloys such as electrum, bronze, pewter, and steel (Book XXXIV).

He is critical of greed for gold, such as the absurdity of using the metal for coins in the early Republic. He gives examples of the way rulers proclaimed their prowess by exhibiting gold looted from their campaigns, such as that by Claudius after conquering Britain, and tells the stories of Midas and Croesus. He discusses why gold is unique in its malleability and ductility, far greater than any other metal. The examples given are its ability to be beaten into fine foil with just one ounce producing 750 leaves four inches square. Fine gold wire can be woven into cloth, although imperial clothes usually combined it with natural fibres like wool. He once saw Agrippina the Younger, wife of Claudius, at a public show on the Fucine Lake involving a naval battle, wearing a military cloak made of gold. He rejects Herodotus's claims of Indian gold obtained by ants or dug up by griffins in Scythia.

Silver, he writes, does not occur in native form and has to be mined, usually occurring with lead ores. Spain produced the most silver in his time, many of the mines having been started by Hannibal. One of the largest had galleries running up to two miles into the mountain, while men worked day and night draining the mine in shifts. Pliny is probably referring to the reverse overshot water-wheels operated by treadmill and found in Roman mines. Britain, he says, is very rich in lead, which is found on the surface at many places, and thus very easy to extract; production was so high that a law was passed attempting to restrict mining.

Fraud and forgery are described in detail; in particular coin counterfeiting by mixing copper with silver, or even admixture with iron. Tests had been developed for counterfeit coins and proved very popular with the victims, mostly ordinary people. He deals with the liquid metal mercury, also found in silver mines. He records that it is toxic, and amalgamates with gold, so is used for refining and extracting that metal. He says mercury is used for gilding copper, while antimony is found in silver mines and is used as an eyebrow cosmetic.

The main ore of mercury is cinnabar, long used as a pigment by painters. He says that the colour is similar to scolecium, probably the kermes insect. The dust is very toxic, so workers handling the material wear face masks of bladder skin. Copper and bronze are, says Pliny, most famous for their use in statues including colossi, gigantic statues as tall as towers, the most famous being the Colossus of Rhodes. He personally saw the massive statue of Nero in Rome, which was removed after the emperor's death. The face of the statue was modified shortly after Nero's death during Vespasian's reign, to make it a statue of Sol. Hadrian moved it, with the help of the architect Decrianus and 24 elephants, to a position next to the Flavian Amphitheatre (now called the Colosseum).

Pliny gives a special place to iron, distinguishing the hardness of steel from what is now called wrought iron, a softer grade. He is scathing about the use of iron in warfare.

Mineralogy

In the last two books of the work (Books XXXVI and XXXVII), Pliny describes many different minerals and gemstones, building on works by Theophrastus and other authors. The topic concentrates on the most valuable gemstones, and he criticises the obsession with luxury products such as engraved gems and hardstone carvings. He provides a thorough discussion of the properties of fluorspar, noting that it is carved into vases and other decorative objects. The account of magnetism includes the myth of Magnes the shepherd.

Pliny moves into crystallography and mineralogy, describing the octahedral shape of the diamond and recording that diamond dust is used by gem engravers to cut and polish other gems, owing to its great hardness. He states that rock crystal is valuable for its transparency and hardness, and can be carved into vessels and implements. He relates the story of a woman who owned a ladle made of the mineral, paying the sum of 150,000 sesterces for the item. Nero deliberately broke two crystal cups when he realised that he was about to be deposed, so denying their use to anyone else.

Pliny returns to the problem of fraud and the detection of false gems using several tests, including the scratch test, where counterfeit gems can be marked by a steel file, and genuine ones not. Perhaps it refers to glass imitations of jewellery gemstones. He refers to using one hard mineral to scratch another, presaging the Mohs hardness scale. Diamond sits at the top of the series because, Pliny says, it will scratch all other minerals.

Art history

Pliny's chapters on Roman and Greek art are especially valuable because his work is virtually the only available classical source of information on the subject.

In the history of art, the original Greek authorities are Duris of Samos, Xenocrates of Sicyon, and Antigonus of Carystus. The anecdotic element has been ascribed to Duris (XXXIV:61); the notices of the successive developments of art and the list of workers in bronze and painters to Xenocrates; and a large amount of miscellaneous information to Antigonus. Both Xenocrates and Antigonus are named in connection with Parrhasius (XXXV:68), while Antigonus is named in the indexes of XXXIII–XXXIV as a writer on the art of embossing metal, or working it in ornamental relief or intaglio.

Greek epigrams contribute their share in Pliny's descriptions of pictures and statues. One of the minor authorities for books XXXIV–XXXV is Heliodorus of Athens, the author of a work on the monuments of Athens. In the indices to XXXIII–XXXVI, an important place is assigned to Pasiteles of Naples, the author of a work in five volumes on famous works of art (XXXVI:40), probably incorporating the substance of the earlier Greek treatises; but Pliny's indebtedness to Pasiteles is denied by Kalkmann, who holds that Pliny used the chronological work of Apollodorus of Athens, as well as a current catalogue of artists. Pliny's knowledge of the Greek authorities was probably mainly due to Varro, whom he often quotes (e.g. XXXIV:56, XXXV:113, 156, XXXVI:17, 39, 41).

For a number of items relating to works of art near the coast of Asia Minor and in the adjacent islands, Pliny was indebted to the general, statesman, orator and historian Gaius Licinius Mucianus, who died before 77. Pliny mentions the works of art collected by Vespasian in the Temple of Peace and in his other galleries (XXXIV:84), but much of his information about the position of such works in Rome is from books, not personal observation. The main merit of his account of ancient art, the only classical work of its kind, is that it is a compilation ultimately founded on the lost textbooks of Xenocrates and on the biographies of Duris and Antigonus.

In several passages, he gives proof of independent observation (XXXIV:38, 46, 63, XXXV:17, 20, 116 seq.). He prefers the marble Laocoön and his Sons in the palace of Titus (widely believed to be the statue that is now in the Vatican) to all the pictures and bronzes in the world (XXXVI:37). The statue is attributed by Pliny to three sculptors from the island of Rhodes: Agesander, Athenodoros (possibly son of Agesander) and Polydorus.

In the temple near the Flaminian Circus, Pliny admires the Ares and the Aphrodite of Scopas, "which would suffice to give renown to any other spot". He adds:

At Rome indeed the works of art are legion; besides, one effaces another from the memory and, however beautiful they may be, we are distracted by the overpowering claims of duty and business; for to admire art we need leisure and profound stillness (XXXVI:27).

Mining

Pliny provides lucid descriptions of Roman mining. He describes gold mining in detail, with large-scale use of water to scour alluvial gold deposits. The description probably refers to mining in Northern Spain, especially at the large Las Médulas site. Pliny describes methods of underground mining, including the use of fire-setting to attack the gold-bearing rock and so extract the ore. In another part of his work, Pliny describes the use of undermining to gain access to the veins. Pliny was scathing about the search for precious metals and gemstones: "Gangadia or quartzite is considered the hardest of all things – except for the greed for gold, which is even more stubborn."

Book XXXIV covers the base metals, their uses and their extraction. Copper mining is mentioned, using a variety of ores including copper pyrites and marcasite, some of the mining being underground, some on the surface. Iron mining is covered, followed by lead and tin.

Reception

Medieval and early modern

The anonymous fourth-century compilation Medicina Plinii contains more than 1,100 pharmacological recipes, the vast majority of them from the Historia naturalis; perhaps because Pliny's name was attached to it, it enjoyed huge popularity in the Middle Ages.

Isidore of Seville's Etymologiae (The Etymologies, c. 600–625) quotes from Pliny 45 times in Book XII alone; Books XII, XIII and XIV are all based largely on the Natural History. Through Isidore, Vincent of Beauvais's Speculum Maius (The Great Mirror, c. 1235–1264) also used Pliny as a source for his own work. In this regard, Pliny's influence over the medieval period has been argued to be quite extensive. For example, one twentieth century historian has argued that Pliny's reliance on book-based knowledge, and not direct observation, shaped intellectual life to the degree that it "stymie[d] the progress of western science". This sentiment can be observed in the early modern period when Niccolò Leoniceno's 1509 De Erroribus Plinii ("On Pliny's Errors") attacked Pliny for lacking a proper scientific method, unlike Theophrastus or Dioscorides, and for lacking knowledge of philosophy or medicine.

Sir Thomas Browne expressed scepticism about Pliny's dependability in his 1646 Pseudodoxia Epidemica:

Now what is very strange, there is scarce a popular error passant in our days, which is not either directly expressed, or diductively contained in this Work; which being in the hands of most men, hath proved a powerful occasion of their propagation. Wherein notwithstanding the credulity of the Reader is more condemnable then the curiosity of the Author: for commonly he nameth the Authors from whom he received those accounts, and writes but as he reads, as in his Preface to Vespasian he acknowledgeth.

Modern

Grundy Steiner of Northwestern University, in a 1955 judgement considered by Thomas R. Laehn to represent the collective opinion of Pliny's critics, wrote of Pliny that "He was not an original, creative thinker, nor a pioneer of research to be compared either with Aristotle and Theophrastus or with any of the great moderns. He was, rather, the compiler of a secondary sourcebook."

The Italian author Italo Calvino, in his 1991 book Why Read the Classics?, wrote that while people often consult Pliny's Natural History for facts and curiosities, he is an author who "deserves an extended read, for the measured movement of his prose, which is enlivened by his admiration for everything that exists and his respect for the infinite diversity of all phenomena". Calvino notes that while Pliny is eclectic, he was not uncritical, though his evaluations of sources are inconsistent and unpredictable. Further, Calvino compares Pliny to Immanuel Kant, in that God is prevented by logic from conflicting with reason, even though (in Calvino's view) Pliny makes a pantheistic identification of God as being immanent in nature. As for destiny, Calvino writes:

it is impossible to force that variable which is destiny into the natural history of man: this is the sense of the pages that Pliny devotes to the vicissitudes of fortune, to the unpredictability of the length of any life, to the pointlessness of astrology, to disease and death.

The art historian Jacob Isager writes in the introduction to his analysis of Pliny's chapters on art in the Natural History that his intention is:

to show how Pliny in his encyclopedic work – which is the result of adaptations from many earlier writers and according to Pliny himself was intended as a reference work – nevertheless throughout expresses a basic attitude to Man and his relationship with Nature; how he understands Man's role as an inventor ("scientist and artist"); and finally his attitude to the use and abuse of Nature's and Man's creations, to progress and decay.

More specifically, Isager writes that "the guiding principle in Pliny's treatment of Greek and Roman art is the function of art in society", while Pliny "uses his art history to express opinions about the ideology of the state". Paula Findlen, writing in the Cambridge History of Science, asserts that

Natural history was an ancient form of scientific knowledge, most closely associated with the writings of the Roman encyclopedist Pliny the Elder ... His loquacious and witty Historia naturalis offered an expansive definition of this subject. [It] broadly described all entities found in nature, or derived from nature, that could be seen in the Roman world and read about in its books: art, artifacts, and peoples as well as animals, plants, and minerals were included in his project.

Findlen contrasts Pliny's approach with that of his intellectual predecessors Aristotle and Theophrastus, who sought general causes of natural phenomena, while Pliny was more interested in cataloguing natural wonders, and his contemporary Dioscorides explored nature for its uses in Roman medicine in his great work De Materia Medica. In the view of Mary Beagon, writing in The Classical Tradition in 2010:

the Historia naturalis has regained its status to a greater extent than at any time since the advent of Humanism. Work by those with scientific as well as philological expertise has resulted in improvements both to Pliny's text and to his reputation as a scientist. The essential coherence of his enterprise has also been rediscovered, and his ambitious portrayal, in all its manifestations, of 'nature, that is, life'.. is recognized as a unique cultural record of its time.