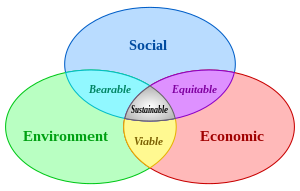

Fair trade is an arrangement designed to help producers in growing countries achieve sustainable and equitable trade relationships. The fair trade movement combines the payment of higher prices to exporters with improved social and environmental standards. The movement focuses in particular on commodities, or products that are typically exported from developing countries to developed countries, but is also used in domestic markets (e.g., Brazil, the United Kingdom, and Bangladesh), most notably for handicrafts, coffee, cocoa, wine, sugar, fruit, flowers, and gold.

Fair trade labelling organizations commonly use a definition of fair trade developed by FINE, an informal association of four international fair trade networks: Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International, World Fair Trade Organization (WFTO), Network of European Worldshops, and European Fair Trade Association (EFTA). Fair trade, by this definition, is a trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency, and respect, that seeks greater equity in international trade. Fair trade organizations, backed by consumers, support producers, raise awareness, and campaign for changes in the rules and practice of conventional international trade.

There are several recognized fair trade certifiers, including Fairtrade International (formerly called FLO, Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International), IMO, Make Trade Fair, and Eco-Social. Additionally, Fair Trade USA, formerly a licensing agency for the Fairtrade International label, broke from the system and implemented its own fair trade labelling scheme, which expanded the scope of fair trade to include independent smallholders and estates for all crops. In 2008, Fairtrade International certified approximately (€3.4B) of products.

On 6 June 2008, Wales became the world's first Fair Trade Nation; they were followed by Scotland in February 2013. The fair trade movement is popular in the UK, where there are over 500 Fairtrade towns, 118 universities, over 6,000 churches, and over 4,000 UK schools registered in the Fairtrade Schools Scheme. In 2011, more than 1.2 million farmers and workers in more than 60 countries participated in Fairtrade International's fair trade system, which included €65 million in fairtrade premium paid to producers for use developing their communities.

Some criticisms have been raised about fair trade systems. One 2015 study concluded that producer benefits were close to zero because there was an oversupply of certification, and only a fraction of produce classified as fair trade was actually sold on fair trade markets, just enough to recoup the costs of certification. A study published by the Journal of Economic Perspectives however suggests that Fair Trade does achieve many of its intended goals, although on a comparatively modest scale relative to the size of national economies. Some research indicates that the implementation of certain fair trade standards can cause greater inequalities in some markets where these rigid rules are inappropriate for the specific market. In the fair trade debate there are complaints of failure to enforce the fair trade standards, with producers, cooperatives, importers, and packers profiting by evading them. One proposed alternative to fair trade is direct trade, which eliminates the overhead of the fair trade certification and allows suppliers to receive higher prices much closer to the retail value of the end product. Some suppliers use relationships started in a fair trade system to autonomously springboard into direct sales relationships they negotiate themselves, whereas other direct trade systems are supplier-initiated for social responsibility reasons similar to a fair trade systems.

System

A large number of fair trade and ethical marketing organizations employ a variety of marketing strategies. Most fair trade marketers believe it is necessary to sell the products through supermarkets to get a sufficient volume of trade to affect the developing world. In 2018, nearly 700,000 metric tons of fair-trade bananas were sold worldwide, with the next largest fair-trade commodity being cocoa beans (260,000 tons) then coffee beans (207,000 tons). The biggest product in the market in terms of units was fair-trade flowers, with over 825 million units sold.

To gain a licence to use the FAIRTRADE mark, businesses need to apply for products to be certified by submitting information about their supply chain. Then they can have individual products certified depending on how these are sourced. Coffee packers in developed countries pay a fee to the Fairtrade Foundation for the right to use the brand and logo. Packers and retailers can charge as much as they want for the coffee. The coffee has to come from a certified fair trade cooperative, and there is a minimum price when the world market is oversupplied. Additionally, the cooperatives are paid an additional 10c per pound premium by buyers for community development projects. The cooperatives can, on average, sell only a third of their output as fair trade, because of lack of demand, and sell the rest at world prices. The exporting cooperative can spend the money in several ways. Some go to meeting the costs of conformity and certification: as they have to meet fair trade standards on all their produce, they have to recover the costs from a small part of their turnover, sometimes as little as 8%, and may not make any profit. Some meet other costs. Some is spent on social projects such as building schools, health clinics, and baseball pitches. Sometimes there is money left over for the farmers. The cooperatives sometimes pay farmers a higher price than farmers do, sometimes less, but there is no evidence on which is more common.

The marketing system for fair trade and non-fair trade coffee is identical in the consuming and developing countries, using mostly the same importing, packing, distributing, and retailing firms used worldwide. Some independent brands operate a "virtual company", paying importers, packers and distributors, and advertising agencies to handle their brand, for cost reasons. In the producing country, fair trade is marketed only by fair trade cooperatives, while other coffee is marketed by fair trade cooperatives (as uncertified coffee), by other cooperatives, and by ordinary traders.

To become a certified fair trade producer, the primary cooperative and its member farmers must operate to certain political standards, imposed from Europe. FLO-CERT, the for-profit side, handles producer certification, inspecting and certifying producer organizations in more than 50 countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. In the fair trade debate there are many complaints of failure to enforce these standards, with producers, cooperatives, importers, and packers profiting by evading them.

There remain many fair trade organizations that adhere more or less to the original objectives of fair trade and that market products through alternative channels where possible and through specialist fair trade shops, but they have a small proportion of the total market.

Effect on growers

Fair trade benefits workers in developing countries, considerably or just a little. The nature of fair trade makes it a global phenomenon; therefore, there are diverse motives for group formation related to fair trade. The social transformation caused by the fair trade movement also varies around the world.

A study of coffee growers in Guatemala illustrates the effect of fair trade practices on growers. In this study, thirty-four farmers were interviewed. Of those thirty-four growers, twenty-two had an understanding of fair trade based on internationally recognized definitions, for example, describing fair trade in market and economical terms or knowing what the social premium is and how their cooperative has used it. Three growers explained a deep understanding of fair trade, showing a knowledge of both fair market principles and how fair trade affects them socially. Nine growers had erroneous or no knowledge of Fair Trade. The three growers who had a deeper knowledge of the social implications of fair trade all had responsibilities within their cooperatives. One was a manager, one was in charge of the wet mill, and one was his group's treasurer. These farmers did not have a pattern in terms of years of education, age, or years of membership in the cooperative; their answers to the questions, "Why did you join?" differentiate them from other members and explain why they have such an extensive knowledge of fair trade. These farmers cited switching to organic farming, wanting to raise money for social projects, and more training offered as reasons for joining the cooperative, other than receiving a better price for their coffee.

Many farmers around the world are unaware of fair trade practices that they could be implementing to earn a higher wage. Coffee is one of the most highly traded commodities in the world, yet the farmers who grow it typically earn less than $2 a day. When surveyed, farmers from Cooperativa Agraria Cafetalera Pangoa (CAC Pangoa) in San Martín de Pangoa, Peru, could answer positively that they have heard about fair trade, but were not able to give a detailed description about what fair trade is. They could, however, identify fair trade based on some of its possible benefits to their community. When asked, farmers responded that fair trade has had a positive effect on their lives and communities. They also wanted consumers to know that fair trade is important for supporting their families and their cooperatives.

Some producers also profit from the indirect benefits of fair trade practices. Fair trade cooperatives create a space of solidarity and promote an entrepreneurial spirit among growers. When growers feel like they have control over their own lives within the network of their cooperative, it can be empowering. Operating a profitable business allows growers to think about their future, rather than worrying about how they are going to survive in poverty.

As far as farmers' satisfaction with the fair trade system, growers want consumers to know that fair trade has provided important support to their families and their cooperative. Overall, farmers are satisfied with the current fair trade system, but some farmers, such as the Mazaronquiari group from CAC Pangoa, desire yet a higher price for their products in order to live a higher quality of life.

A component of trade is the social premium that buyers of fair trade goods pay to the producers or producer-groups of such goods. An important factor of the fair trade social premium is that the producers or producer-groups decide where and how it is spent. These premiums usually go towards socioeconomic development, wherever the producers or producer-groups see fit. Within producer-groups, the decisions about how the social premium will be spent are handled democratically, with transparency and participation.

Producers and producer-groups spend this social premium to support socioeconomic development in a variety of ways. One common way to spend the social premium of fair trade is to privately invest in public goods that infrastructure and the government are lacking in. These include environmental initiatives, public schools, and water projects. At some point, all producer-groups re-invest their social premium back into their farms and businesses. They buy capital, like trucks and machinery, and education for their members, like organic farming education. Thirty-eight percent of producer-groups spend the social premium in its entirety on themselves, but the rest invest in public goods, like paying for teachers' salaries, providing a community health care clinic, and improving infrastructure, such as bringing in electricity and bettering roads.

Farmers' organisations that use their social premium for public goods often finance educational scholarships. For example, Costa Rican coffee cooperative Coocafé has supported hundreds of children and youth at school and university through the financing of scholarships from funding from their fair trade social premium. In terms of education, the social premium can be used to build and furnish schools too.

Organizations promoting fair trade

Most fair trade import organizations are members of, or certified by, one of several national or international federations. These federations coordinate, promote, and facilitate the work of fair trade organizations. The following are some of the largest:

- Fairtrade International, created in 1997, is an association of three producer networks and twenty national labeling initiatives that develop fair trade standards, license buyers, label usage, and market the Fair trade Certification Mark in consuming countries. The Fairtrade International labeling system is the largest and most widely recognized standard setting and certification body for labeled Fair trade. Formerly named Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International, it changed its name to Fairtrade International in 2009, when its producer certification and standard setting activities were separated into two separate, but connected entities. FLO-CERT, the for-profit side, handles producer certification, inspecting and certifying producer organizations in more than 50 countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Fairtrade International, the nonprofit arm, oversees standards development and licensing organization activity. Only products from certain developing countries are eligible for certification, and for some products such as coffee and cocoa, certification is restricted to cooperatives. Cooperatives and large estates with hired labor may be certified for bananas, tea, and other crops.

- Fair Trade USA is an independent, nonprofit organization that sets standards, certifies, and labels products that promote sustainable livelihoods for farmers and workers and protect the environment. Founded in 1998, Fair Trade USA currently partners with over 1,000 brands, as well as 1.3 million farmers and workers across the globe.

- Global Goods Partners (GGP) is a fair-trade nonprofit organization founded in 2005 that provides support and U.S. market access to women-led cooperatives in the developing world.

- World Fair Trade Organization (formerly the International Fair Trade Association) is a global association created in 1989 of fair trade producer cooperatives and associations, export marketing companies, importers, retailers, national and regional fair trade networks, and fair trade support organizations. In 2004 WFTO launched the FTO Mark which identifies registered fair trade organizations (as opposed to the FLO system, which labels products).

- The Network of European Worldshops (NEWS), created in 1994, is the umbrella network of 15 national worldshop associations in 13 countries in Europe.

- The European Fair Trade Association (EFTA), created in 1990, is a network of European alternative trading organizations that import products from some 400 economically disadvantaged producer groups in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. EFTA's goal is to promote fair trade and to make fair trade importing more efficient and effective. The organization also publishes yearly various publications on the evolution of the fair trade market. EFTA currently has eleven members in nine countries.

In 1998, the four federations listed above joined together as FINE, an informal association whose goal is to harmonize fair trade standards and guidelines, increase the quality and efficiency of fair trade monitoring systems, and advocate fair trade politically.

- Additional certifiers include IMO (Fair for Life, Social and Fair Trade labels), and Eco-Social.

- The Fair Trade Federation (FTF), created in 1994, is an association of Canadian and American fair trade wholesalers, importers, and retailers. The organization links its members to fair trade producer groups while acting as a clearinghouse for information on fair trade and providing resources and networking opportunities to its members. Members self-certify adherence to defined fair trade principles for 100% of their purchasing/business. Those who sell products certifiable by Fairtrade International must be 100% certified by Fairtrade International to join FTF.

Student groups have also been increasingly promoting fair trade products. Although hundreds of independent student organizations are active worldwide, most groups in North America are either affiliated with United Students for Fair Trade (USA), the Canadian Student Fair Trade Network (Canada), or Fair Trade Campaigns (USA), which also houses Fair Trade Universities and Fair Trade Schools.

The involvement of church organizations has been and continues to be an integral part of the fair trade movement:

- Ten Thousand Villages is affiliated with the Mennonite Central Committee

- SERRV is partnered with Catholic Relief Services and Lutheran World Relief

- Village Markets is a Lutheran Fair Trade organization connecting mission sites around the world with churches in the United States

- Catholic Relief Services has their own Fair Trade mission in CRS Fair Trade

History

The first attempts to commercialize fair trade goods in Northern markets were initiated in the 1940s and 1950s by religious groups and various politically oriented non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Ten Thousand Villages, an NGO within the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC), and SERRV International were the first, in 1946 and 1949 respectively, to develop fair trade supply chains in developing countries. The products, almost exclusively handicrafts ranging from jute goods to cross-stitch work, were mostly sold in churches or fairs. The goods themselves had often no other function than to indicate that a donation had been made.

Solidarity trade

The current fair trade movement was shaped in Europe in the 1960s. Fair trade during that period was often seen as a political gesture against neo-imperialism: radical student movements began targeting multinational corporations, and concerns emerged that traditional business models were fundamentally flawed. The slogan at the time, "Trade not Aid", gained international recognition in 1968 when it was adopted by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) to put the emphasis on the establishment of fair trade relations with the developing world.

1965 saw the creation of the first alternative trading organization (ATO): that year, British NGO Oxfam launched "Helping-by-Selling", a program that sold imported handicrafts in Oxfam stores in the UK and from mail-order catalogues.

By 1968, the Whole Earth Catalog was connecting thousands of specialized merchants, artisans, and scientists directly with consumers who were interested in supporting independent producers, with the goal of bypassing corporate retail and department stores. The Whole Earth Catalog sought to balance the international free market by allowing direct purchasing of goods produced primarily in the U.S. and Canada but also in Central and South America.

In 1969, the first worldshop opened its doors in the Netherlands. It aimed at bringing the principles of fair trade to the retail sector by selling almost exclusively goods produced under fair trade terms in "underdeveloped regions". The first shop was run by volunteers and was so successful that dozens of similar shops soon went into business in the Benelux countries, Germany, and other Western European countries.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, segments of the fair trade movement worked to find markets for products from countries that were excluded from the mainstream trading channels for political reasons. Thousands of volunteers sold coffee from Angola and Nicaragua in worldshops, in the back of churches, from their homes, and from stands in public places, using the products as a vehicle to deliver their message: give disadvantaged producers in developing countries a fair chance on the world's market.[citation needed]

Handicrafts vs. agricultural goods

In the early 1980s, alternative trading organizations faced challenges: the novelty of fair trade products began to wear off, demand reached a plateau, and some handicrafts began to look "tired and old fashioned" in the marketplace. The decline of segments of the handicrafts market forced fair trade supporters to rethink their business model and their goals. Moreover, several fair trade supporters were worried by the effect on small farmers of structural reforms in the agricultural sector as well as the fall in commodity prices. Many came to believe it was the movement's responsibility to address the issue and remedies usable in the ongoing crisis in the industry.

In subsequent years, fair trade agricultural commodities played an important role in the growth of many ATOs: successful on the market, they offered a source of income for producers and provided alternative trading organizations a complement to the handicrafts market. The first fair trade agricultural products were tea and coffee, followed by: dried fruits, cocoa, sugar, fruit juices, rice, spices, and nuts. While in 1992, a sales value ratio of 80% handcrafts to 20% agricultural goods was the norm, in 2002 handcrafts amounted to 25% of fair trade sales while commodity food was up at 69%.

Rise of labeling initiatives

Sales of fair trade products only took off with the arrival of the first Fairtrade certification initiatives. Although buoyed by growing sales, fair trade had been generally confined to small worldshops scattered across Europe and, to a lesser extent, North America. Some felt that these shops were too disconnected from the rhythm and the lifestyle of contemporary developed societies. The inconvenience of going to them to buy only a product or two was too high even for the most dedicated customers. The only way to increase sale opportunities was to offer fair trade products where consumers normally shop, in large distribution channels. The problem was to find a way to expand distribution without compromising consumer trust in fair trade products and in their origins.

A solution was found in 1988, when the first fair trade certification initiative, Max Havelaar, was created in the Netherlands under the initiative of Nico Roozen, Frans Van Der Hoff, and Dutch development NGO Solidaridad. The independent certification allowed the goods to be sold outside the worldshops and into the mainstream, reaching a larger consumer segment and boosting fair trade sales significantly. The labeling initiative also allowed customers and distributors alike to track the origin of the goods to confirm that the products were really benefiting the producers at the end of the supply chain.

The concept caught on: in ensuing years, similar non-profit Fairtrade labelling organizations were set up in other European countries and North America. In 1997, a process of convergence among "LIs" ("Labeling Initiatives") led to the creation of Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International, an umbrella organization whose mission is to set fair trade standards, support, inspect, and certify disadvantaged producers, and harmonize the fair trade message across the movement.

In 2002, FLO launched an International Fairtrade Certification Mark. The goals were to improve the visibility of the Mark on supermarket shelves, facilitate cross border trade, and simplify procedures for both producers and importers. The certification mark is used in more than 50 countries and on dozens of different products, based on FLO's certification for coffee, tea, rice, bananas, mangoes, cocoa, cotton, sugar, honey, fruit juices, nuts, fresh fruit, quinoa, herbs and spices, wine, footballs, etc.

With ethical labeling, consumers can take moral responsibility for their economic decisions and actions. This supports the notion of fair trade practices as "moral economies". The presence of labeling gives consumers the feeling of "doing the right thing" with a simple purchase.

Labeling practices place the burden of getting certification on the producers in the Global South, furthering inequality between the Global North and the Global South. The process of securing certification is burdensome and expensive. Northern consumers are able to make a simple choice while being spared these burdens and expenses.

Psychology

Consumers of fair trade products usually make the intentional choice to purchase fair trade goods based on attitude, moral norms, perceived behavioral control, and social norms. It is useful to include of measure of moral norms to improve the predictive power of intentions to buy fair trade over the basic predictors, like attitude and perceived behavioral control.

University students have significantly increased their consumption of fair trade products over the last several decades. Women college students have a more favorable attitude than men toward buying fair trade products and they feel more morally obligated to do so. Women are also reported to have stronger intentions to buy fair trade products. Producers organize and strive for fair trade certification for several reasons, either through religious ties, wants for social justice, wants for autonomy, political liberalization, or simply because they want to be paid more for their labor efforts and products. Farmers are more likely to identify with organic farming than fair trade farming practices because organic farming is a visible way that these farmers are different from their neighbors and it influences the way they farm. They place importance on natural growing methods. Fair trade farmers are also more likely to attribute their higher prices to the quality of their products rather than fair market prices.

Product certification

Fairtrade labelling (usually simply Fairtrade or Fair Trade Certified in the United States) is a certification system that allows consumers to identify goods that meet certain standards. Overseen by a standard-setting body (Fairtrade International) and a certification body (FLO-CERT), the system involves independent auditing of producers and traders to ensure the standards are met. For a product to carry either the International Fairtrade Certification Mark or the Fair Trade Certified Mark, it must come from FLO-CERT inspected and certified producer organizations. The crops must be grown and harvested in accordance with the standards set by FLO International. The supply chain must be monitored by FLO-CERT, to ensure the integrity of the labelled product.

Fairtrade certification purports to guarantee not only fair prices, but also ethical purchasing principles. These principles include adherence to ILO agreements such as those banning child and slave labour, guaranteeing a safe workplace and the right to unionise, adherence to the United Nations charter of human rights, a fair price that covers the cost of production and facilitates social development, and protection of the environment. The Fairtrade certification also attempts to promote long-term business relationships between buyers and sellers, crop pre-financing, and greater transparency throughout the supply chain.

The Fairtrade certification system covers a growing range of products, including bananas, honey, coffee, oranges, Cocoa bean, cocoa, cotton, dried and fresh fruits and vegetables, juices, nuts and oil seeds, quinoa, rice, spices, sugar, tea, and wine. Companies offering products that meet Fairtrade standards may apply for licences to use one of the Fairtrade Certification Marks for those products. The International Fairtrade Certification Mark was launched in 2002 by FLO, and replaced twelve Marks used by various Fairtrade labelling initiatives. The new Certification Mark is currently used worldwide (with the exception of the United States). The Fair Trade Certified Mark is still used to identify Fairtrade goods in the United States.

The fair trade industry standards provided by Fairtrade International use the word "producer" in many different senses, often in the same specification document. Sometimes it refers to farmers, sometimes to the primary cooperatives they belong to, to the secondary cooperatives that the primary cooperatives belong to, or to the tertiary cooperatives that the secondary cooperatives may belong to but "Producer [also] means any entity that has been certified under the Fairtrade International Generic Fairtrade Standard for Small Producer Organizations, Generic Fairtrade Standard for Hired Labour Situations, or Generic Fairtrade Standard for Contract Production." The word is used in all these meanings in key documents. In practice, when price and credit are discussed, "producer" means the exporting organization, "For small producers' organizations, payment must be made directly to the certified small producers' organization". and "In the case of a small producers' organization [e.g. for coffee], Fairtrade Minimum Prices are set at the level of the Producer Organization, not at the level of individual producers (members of the organization)" which means that the "producer" here is halfway up the marketing chain between the farmer and the consumer. The part of the standards referring to cultivation, environment, pesticides, and child labour has the farmer as "producer".

Alternative trading organizations

An alternative trading organization (ATO) is usually a non-governmental organization (NGO) or mission-driven business aligned with the fair trade movement that aims "to contribute to the alleviation of poverty in developing regions of the world by establishing a system of trade that allows marginalized producers in developing regions to gain access to developed markets." ATOs have fair trade at the core of their mission and activities, using it as a development tool to support disadvantaged producers and to reduce poverty and combining their marketing with awareness-raising and campaigning.

ATOs are often based on political and religious groups, though their secular purpose precludes sectarian identification and evangelical activity. The grassroots political-action agenda of ATOs associates them with progressive political causes active since the 1960s: foremost, a belief in collective action and commitment to moral principles based on social, economic, and trade justice.

According to EFTA, the defining characteristic of ATOs is equal partnership and respect–partnership between the developing region producers and importers, shops, labelling organizations, and consumers. Alternative trade "humanizes" the trade process–making the producer-consumer chain as short as possible so that consumers become aware of the culture, identity, and conditions in which producers live. All actors are committed to the principle of alternative trade, the need for advocacy in their working relations, and the importance of awareness-raising and advocacy work. Examples of such organisations are Ten Thousand Villages, Greenheart Shop, Equal Exchange, and SERRV International in the U.S. and Equal Exchange Trading, Traidcraft, Oxfam Trading, Twin Trading, and Alter Eco in Europe as well as Siem Fair Trade Fashion in Australia.

Universities

The concept of a Fair Trade school or Fair Trade university emerged from the United Kingdom, where the Fairtrade Foundation maintains a list of colleges and schools that comply with the requirements to be labeled such a university. In order to be considered a Fair Trade University, a university must establish a Fairtrade School Steering Group. They must have a written and implemented, school-wide, fair trade policy. The school or university must be dedicated to selling and using Fair Trade products. They must learn and educate about Fair Trade issues. Finally, they must promote fair trade not only within the school but throughout the wider community.

A Fair Trade University develops all aspects of fair trade practices in their coursework. In 2007, the Director of the Environmental Studies program at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, David Barnhill, endeavored to become the first Fair Trade University. This received positive reactions from faculty and students. To begin, the university agreed that it would need support from four institutional groups—faculty, staff, support staff, and students—to maximize support and educational efforts. The University endorsed the Earth Charter and created a Campus Sustainability Plan to align with the efforts of becoming a Fair Trade University.

The University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh also offers courses in different disciplines that implement fair trade learning. They offer a business course with a trip to Peru to visit coffee farmers, an environmental science class that discusses fair trade as a way for cleaner food systems, an English course that focuses on the Earth Charter and the application of fair trade principles, and several upper-level anthropology courses focused on fair trade.

In 2010, the University of California, San Diego became the second Fair Trade University in the United States. UC San Diego considered the efforts of the Fairtrade Foundation in the UK, but wanted to be more detailed about how their declaration as a Fair Trade University would change the way on-campus franchises do business with the university. They required constant assessment and improvement. Being a Fair Trade University for UC San Diego is a promise between the university and the students about the continual effort by the university to increase the accessibility of fair trade-certified food and drinks and to encourage sustainability in other ways, such as buying from local, organic farmers and decreasing waste.

Fair Trade Universities have been successful because they are a "feel good" movement. Because the movement has an established history, it is not just a fad. It raises awareness about an issue and offers a solution. The solution is an easy one for college students to handle: paying about five cents more for a cup of coffee or tea.

Worldshops

Worldshops, or fair trade shops, are specialized retail outlets that offer and promote fair trade products. Worldshops also typically organize educational fair trade activities and play a role in trade justice and other North-South political campaigns. Worldshops are often not-for-profit organizations run by local volunteer networks. The movement emerged in Europe and a majority of worldshops are still based on the continent, but worldshops also exist in North America, Australia, and New Zealand.

Worldshops aim to make trade as direct and fair with the trading partners as possible. Usually, this means a producer in a developing country and consumers in industrialized countries. Worldshops aim to pay the producers a fair price that guarantees substinence and positive social development. They often cut out intermediaries in the import chain. A web movement began in the 2000s to provide fair trade items at fair prices to consumers. One is "Fair Trade a Day" on which a different fair trade item is featured each day.

World wide

Every year the sales of Fair Trade products grow close to 30% and in 2004 were worth over US$500 million. In the case of coffee, sales grow nearly 50% per year in certain countries. In 2002, 16,000 tons of Fairtrade coffee were purchased by consumers in 17 countries. "Fair trade coffee is currently produced in 24 countries in Latin America, Africa, and Asia". The 165 FLO associations in Latin America and Caribbean are located in 14 countries and As of 2004 together export over 85% of the world's Fair Trade coffee. There is a North/South divide of fair trade products, with producers in the South and consumers in the North. Discrepancies in the perspectives of producers and consumers prompt disputes about how the purchasing power of consumers may or may not promote the development of southern countries. "Purchasing patterns of fairtrade products have remained strong despite the global economic downturn. In 2008, global sales of fairtrade products exceeded US$3.5 billion."

Africa

Africa’s labor market is becoming an integral fragment of the global supply chain (GSC) and is expected to attract foreign direct investment (FDI). As the continent closes its infrastructure gap, it increases its export to the world. Africa's exports, from places like South Africa, Ghana, Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya, were valued at US$24 million As of 2009. Between 2004 and 2006, Africa expanded the number of FLO-certified producer groups from 78 to 171, nearly half of which are in Kenya; following closely behind are Tanzania and South Africa. The FLO products Africa is known for are tea, cocoa, flowers, and wine. In Africa smallholder cooperatives and plantations produce Fair Trade certified tea. Cocoa-producing countries in West Africa often form cooperatives that produce fair trade cocoa, such as Kuapa Kokoo in Ghana. West African countries without strong fair trade industries are subject to deterioration in cocoa quality as they compete with other countries for a profit. These countries include Cameroon, Nigeria, and the Ivory Coast.

Latin America

Studies in the early 2000s showed that the income, education, and health of coffee producers involved with Fair Trade in Latin America improved in comparison to producers who were not participating. Brazil, Nicaragua, Peru, and Guatemala, having the biggest populations of coffee producers, use some of the most substantial land for coffee production in Latin America and do so by taking part in Fair Trade.

Latin American countries are also large exporters of fair trade bananas. The Dominican Republic is the largest producer of fair trade bananas, followed by Mexico, Ecuador, and Costa Rica. Producers in the Dominican Republic set up associations rather than cooperatives so that individual farmers can each own their own land, but meet regularly.

Fundación Solidaridad was created in Chile to increase the earnings and social participation of handicraft producers. These goods are marketed locally in Chile and internationally. Fair trade handicraft and jewellery production has risen in recent years, aided by North American and European online retailers developing direct relationships to import and sell the products online. The sale of fair trade handicrafts online has aided the development of female artisans in Latin America.

Asia

The Asia Fair Trade Forum aims to increase the competitiveness of fair trade organizations in Asia in the global market. Garment factories in Asian countries including China, Burma, and Bangladesh are regularly accused of human rights violations, including the use of child labour. These violations conflict with the principles outlined by fair trade certifiers. In India, Trade Alternative Reform Action (TARA) Projects, formed in the 1970s, worked to increase production capacity, quality standards, and entrance into markets for home-based craftsmen that were previously unattainable due to their lower caste identity. Fairtrade India was established in 2013 in Bangalore.

Australia

The Fair Trade Association of Australia and New Zealand (FTAANZ) supports two systems of fair trade: The first is as the Australia and New Zealand member of FLO International, which unites Fairtrade producer and labelling initiatives across Europe, Asia, Latin America, North America, Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. The second is the World Fair Trade Organization (WFTO), of more than 450 worldwide members, of which FTAANZ is one. Fairtrade (one word) refers to FLO-certified commodities and associated products. Fair trade (two words) encompasses the wider fair trade movement, including the Fairtrade commodities and other artisan craft products.

Commodities

Fair trade commodities are import/export goods that are certified by a fair trade certification organization such as Fair Trade USA or World Fair Trade Organization. Such organizations are typically overseen by Fairtrade International. Fairtrade International sets international fair trade standards and supports fair trade producers and cooperatives. Sixty percent of the fair trade market consists of food products such as coffee, tea, cocoa, honey, and bananas. Non-food commodities include crafts, textiles, and flowers. Shima Baradaran of Brigham Young University suggests that fair trade techniques could be productively applied to products that might involve child labor. Although fair trade represents only .01% of the food and beverage industry in the United States, it is growing rapidly.

Coffee

Coffee is the most well-established fair trade commodity. Most Fair Trade coffee is Coffea arabica, which is grown at high altitudes. Fair Trade markets emphasize the quality of coffee because they usually appeal to customers who are motivated by taste rather than price. The fair trade movement fixated on coffee first because it is a highly traded commodity for most producing countries, and almost half the world's coffee is produced by smallholder farmers. At first fair trade coffee was sold at small scale; now multinationals like Starbucks and Nestlé use fair trade coffee.

Internationally recognized Fair Trade coffee standards outlined by FLO are as follows: small producers are grouped in democratic cooperatives or groups; buyers and sellers establish long-term, stable relationships; buyers pay the producers at least the minimum Fair Trade price or, when the market price is higher, the market price; and, buyers pay a social premium of US$0.2 per pound of coffee to the producers. The current minimum Fair Trade price for high-grade, washed Arabica coffee is US$1.4 per pound; US$1.7 per pound if the coffee is organic.

Locations

The largest sources of fair trade coffee are Uganda and Tanzania, followed by Latin American countries such as Guatemala and Costa Rica. As of 1999, major importers of fair trade coffee included Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. There is a North/South divide between fair trade consumers and producers. North American countries are not yet among the top importers of fair trade coffee.

Labour

Starbucks began to purchase more fair trade coffee in 2001 because of charges of labor rights violations in Central American plantations. Several competitors, including Nestlé, followed suit. Large corporations that sell non-fair trade coffee take 55% of what consumers pay for coffee while only 10% goes to the producers. Small growers dominate the production of coffee, especially in Latin American countries such as Peru. Coffee is the fastest expanding fairly traded commodity, and an increasing number of producers are small farmers that own their own land and work in cooperatives. The incomes of growers of fair trade coffee beans depend on the market value of coffee where it is consumed, so farmers of fair trade coffee do not necessarily live above the poverty line or get completely fair prices for their commodity.

Unsustainable farming practices can harm plantation owners and laborers. Unsustainable practices such as using chemicals and unshaded growing are risky. Small growers who put themselves at economic risk by not having diverse farming practices could lose money and resources due to fluctuating coffee prices, pest problems, or policy shifts.

The effectiveness of Fairtrade is questionable; workers on Fairtrade farms have a lower standard of living than on similar farms outside the Fairtrade system.

Sustainability

As coffee becomes one of the most important export crops in certain regions such as northern Latin America, nature and agriculture are transformed. Increased productivity requires technological innovations, and the coffee agroecosystem has been changing. In the nineteenth century in Latin America, coffee plantations began replacing sugarcane and subsistence crops. Coffee crops became more managed; they were put into rows and unshaded, meaning diversity of the forest was decreased and Coffea trees shortened. As plant and tree diversity decreased, so did animal diversity. Unshaded plantations allow a higher density of Coffea trees, are less protected from wind and lead to more soil erosion. Technified coffee plantations also use chemicals such as fertilizers, insecticides, and fungicides.

Fair trade certified commodities must adhere to sustainable agro-ecological practices, including reduction of chemical fertilizer use, prevention of erosion, and protection of forests. Coffee plantations are more likely to be fair trade certified if they use traditional farming practices with shading and without chemicals. This protects the biodiversity of the ecosystem and ensures that the land will be usable for farming in the future and not just for short-term planting. In the United States, 85% of fair trade certified coffee is also organic.

Consumer attitudes

Consumers typically have positive attitudes about products that are ethically made. These products may promise fair labor conditions, protection of the environment, and protection of human rights. Fair trade products meet standards like these. Despite positive attitudes toward ethical products such as fair trade commodities, consumers often are not willing to pay higher prices for fair trade coffee. The attitude-behavior gap can help explain why ethical and fair trade products take up less than 1% of the market. Coffee consumers may say they are willing to pay a premium for fair trade coffee, but most consumers are more concerned with the brand, label, and flavor of the coffee. However, socially conscious consumers with a commitment to buying fair trade products are more likely to pay the premium associated with fair trade coffee. When a sufficient number of consumers begin purchasing fair trade, companies will be more likely to carry fair trade products. Safeway Inc. began carrying fair trade coffee after individual consumers dropped off postcards asking for it.

Coffee companies

The following coffee roasters and companies offer fair trade coffee or some roasts that are fair trade certified:

- Anodyne Coffee Roasting Company

- Breve Coffee Company

- Cafedirect

- Counter Culture Coffee

- Equal Exchange

- GEPA

- Green Mountain Coffee Roasters

- Just Us!

- Peace Coffee

- Pura Vida Coffee

Cocoa

Many countries that export cocoa rely on it as their single export crop. In Africa in particular, governments tax cocoa as their main source of revenue. Cocoa is a permanent crop, which means that it occupies land for long periods of time and does not need to be replanted after each harvest.

Locations

Cocoa is farmed in the tropical regions of West Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America. In Latin America, cocoa is produced in Costa Rica, Panama, Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil. Much of the cocoa produced in Latin America is organic and regulated by an Internal control system. Bolivia has fair trade cooperatives that permit a fair share of money for cocoa producers. African cocoa-producing countries include Cameroon, Madagascar, São Tomé and Príncipe, Ghana, Tanzania, Uganda, and Côte d'Ivoire. Côte d'Ivoire exports over a third of the world's cocoa beans. Southeast Asia accounts for about 14% of the world's cocoa production. Major cocoa-producing countries are Indonesia, Malaysia, and Papua New Guinea.

Labour

Africa and other developing countries received low prices for their exported commodities such as cocoa, which caused poverty to abound. Fair trade seeks to establish a system of direct trade from developing countries to counteract this unfair system. Most cocoa comes from small family-run farms in West Africa. These farms have little market access and so rely on middlemen to bring their products to market. Sometimes middlemen are unfair to farmers. Farmers may join an Agricultural cooperative that pays farmers a fair price for their cocoa. One of the main tenets of fair trade is that farmers receive a fair price, but this does not mean that the higher price paid for fair trade cocoa goes directly to the farmers. Much of this money goes to community projects such as water wells rather than to individual farmers. Nevertheless, cooperatives such as fair trade-endorsed Kuapa Kokoo in Ghana are often the only Licensed Buying Companies that will give farmers a fair price and not cheat them or rig sales. Farmers in cooperatives are frequently their own bosses and get bonusesper bag of cocoa beans. These arrangements are not always assured and fair trade organizations can't always buy all of the cocoa available to them from cooperatives.

Marketing

Marketing of fair trade cocoa to European consumers often portrays cocoa farmers as dependent on western purchases for their livelihood and well-being. Showing African cocoa producers in this way is problematic because it is reminiscent of the imperialistic view that Africans cannot live happily without the help of westerners. It portrays the balance of power as being in favor of the consumers rather than the producers.

Consumers often aren't willing to pay the extra price for fair trade cocoa because they do not know what fair trade is. Activist groups can educate consumers about the unethical aspects of unfair trade and thereby promote demand for fairly traded commodities. Activism and ethical consumption not only promote fair trade but also act against powerful corporations such as Mars, Incorporated that refuse to acknowledge the use of forced child labor in the harvesting of their cocoa.

Sustainability

Smallholding farmers frequently lack access not only to markets but also to resources for sustainable cocoa farming practices. Lack of sustainability can be due to pests, diseases that attack cocoa trees, lack of farming supplies, and lack of knowledge about modern farming techniques. One issue pertaining to cocoa plantation sustainability is the amount of time it takes for a cocoa tree to produce pods. A solution is to change the type of cocoa tree being farmed. In Ghana, a hybrid cocoa tree yields two crops after three years rather than the typical one crop after five years.

Cocoa companies

The following chocolate companies use all or some fair trade cocoa in their chocolate:

Harkin-Engel Protocol

The Harkin-Engel Protocol, also commonly known as the Cocoa Protocol, is an international agreement meant to end some of the world's worst forms of child labor, as well as forced labor in the cocoa industry. It was first negotiated by Senator Tom Harkin and Representative Eliot Engel after they watched a documentary that showed the cocoa industry's widespread issue of child slavery and trafficking. The parties involved agreed to a six-article plan:

- Public statement of the need for and terms of an action plan—The cocoa industry acknowledged the problem of forced child labor and will commit "significant resources" to address the problem.

- Formation of multi-sectoral advisory groups—By 1 October 2001, an advisory group will be formed to research labor practices. By 1 December 2001, industry will form an advisory group and formulate appropriate remedies to address the worst forms of child labor.

- Signed joint statement on child labor to be witnessed at the ILO—By 1 December 2001, a statement must be made recognizing the need to end the worst forms of child labor and identify developmental alternatives for the children removed from labor.

- Memorandum of cooperation—By 1 May 2002, Establish a joint action program of research, information exchange, and action to enforce standards to eliminate the worst forms of child labor. Establish a monitor and compliance with the standards.

- Establish a joint foundation—By 1 July 2002, industry will form a foundation to oversee efforts to eliminate the worst forms of child labor. It will perform field projects and be a clearinghouse on best practices.

- Building toward credible standards—By 1 July 2005, the industry will develop and implement industry-wide standards of public certification that cocoa has been grown without any of the worst forms of child labor.

Textiles

Fair trade textiles are primarily made from fair trade cotton. By 2015, nearly 75,000 cotton farmers in developing countries had obtained fair trade certification. The minimum price that Fair trade pays allows cotton farmers to sustain and improve their livelihoods. Fair trade textiles are frequently grouped with fair trade crafts and goods made by artisans in contrast to cocoa, coffee, sugar, tea, and honey, which are agricultural commodities.

Locations

India, Pakistan, and West Africa are the primary exporters of fair trade cotton, although many countries grow fair trade cotton. Production of Fairtrade cotton was initiated in 2004 in four countries in West and Central Africa (Mali, Senegal, Cameroon, and Burkina Faso). Textiles and clothing are exported from Hong Kong, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

Labour

Labour is different for textile production than for agricultural commodities because textile production takes place in a factory, not on a farm. Children are a source of cheap labor, and child labor is prevalent in Pakistan, India, and Nepal. Fair trade cooperatives ensure fair and safe labor practices, and do not allow child labor. Fair trade textile producers are most often women in developing countries. They struggle to meet consumer tastes in North America and Europe. In Nepal, textiles were originally made for household and local use. In the 1990s, women began joining cooperatives and exporting their crafts for profit. Now handicrafts are Nepal's largest export. It is often difficult for women to balance textile production, domestic responsibilities, and agricultural work. Cooperatives foster the growth of democratic communities in which women have a voice despite being historically in underprivileged positions. For fair trade textiles and other crafts to be successful in Western markets, World Fair Trade Organizations require a flexible workforce of artisans in need of stable income, links from consumers to artisans, and a market for quality ethnic products.

Making cotton and textiles "fair trade" does not always benefit laborers. Burkina Faso and Mali export the largest amount of cotton in Africa. Although many cotton plantations in these countries attained fair trade certification in the 1990s, participation in fair trade strengthened existing power relations and inequalities that cause poverty in Africa rather than challenging them. Fair trade does not do much for farmers when it does not challenge the system that marginalizes producers. Despite not empowering farmers, the change to fair trade cotton has positive effects including female participation in cultivation.

Textiles and garments are intricate and require one individual operator, in contrast to the collective farming of coffee and cocoa beans. Textiles are not a straightforward commodity because to be fairly traded, there must be regulation in cotton cultivation, dyeing, stitching, and every other step in the process of textile production. Fair trade textiles are distinct from the sweat-free movement although the two movements intersect at the worker level.

Forced or unfair labor in textile production is not limited to developing countries. Charges of use of sweatshop labor are endemic in the United States. Immigrant women work long hours and receive less than minimum wage. In the United States, there is more of a stigma against child labor than forced labor in general. Consumers in the United States are willing to suspend the importation of textiles made with child labor in other countries but do not expect American exports to be suspended by other countries, even when produced using forced labor.

Clothing and textile companies

The following companies use fair trade production and/or distribution techniques for clothing and textiles:

Seafood

With increasing media scrutiny of the conditions of fishermen, particularly in Southeast Asia, the lack of transparency and traceability in the seafood industry prompted new fair trade efforts. In 2014, Fair Trade USA created its Capture Fisheries Program that led to the first instance of Fair Trade fish being sold globally in 2015. The program "requires fishermen to source and trade according to standards that protect fundamental human rights, prevent forced and child labor, establish safe working conditions, regulate work hours and benefits, and enable responsible resource management."

Large companies and commodities

Large transnational companies have started to use fair trade commodities in their products. In April 2000, Starbucks began offering fair trade coffee in all of their stores. In 2005, the company promised to purchase ten million pounds of fair trade coffee over the next 18 months. This would account for a quarter of the fair trade coffee purchases in the United States and 3% of Starbucks' total coffee purchases. The company maintains that increasing its fair trade purchases would require an unprofitable reconstruction of the supply chain. Fair trade activists have made gains with other companies: Sara Lee Corporation in 2002 and Procter & Gamble (the maker of Folgers) in 2003 agreed to begin selling a small amount of fair trade coffee. Nestlé, the world's biggest coffee trader, began selling a blend of fair trade coffee in 2005. In 2006, The Hershey Company acquired Dagoba, an organic and fair trade chocolate brand.

Much contention surrounds the issue of fair trade products becoming a part of large companies. Starbucks is still only 3% fair trade–enough to appease consumers, but not enough to make a real difference to small farmers, according to some activists. The ethics of buying fair trade from a company that is not committed to the cause are questionable; these products are only making a small dent in a big company even though these companies' products account for a significant portion of global fair trade.

| Business type | Engagement with fair trade products |

|---|---|

| Highest | |

| Fair trade organizations | Equal Exchange |

| Global Crafts | |

| Ten Thousand Villages | |

| Values-driven organizations | The Body Shop |

| Green Mountain Coffee | |

| Pro-active socially responsible businesses | Starbucks |

| Whole Foods

The Ethical Olive | |

| Defensive socially responsible businesses | Procter & Gamble |

| Lowest |

Luxury commodities

There have been efforts to introduce fair trade practices to the luxury goods industry, particularly for gold and diamonds.

Diamonds and sourcing

In parallel to efforts to commoditize diamonds, some industry players launched campaigns to introduce benefits to mining centers in the developing world. Rapaport Fair Trade was established with the goal "to provide ethical education for jewelry suppliers, buyers, first time or seasoned diamond buyers, social activists, students, and anyone interested in jewelry, trends, and ethical luxury."

The company's founder, Martin Rapaport, as well as Kimberley Process initiators Ian Smillie and Global Witness, are among several industry insiders and observers who have called for greater checks and certification programs among other programs to ensure protection for miners and producers in developing countries. Smillie and Global Witness have since withdrawn support for the Kimberley Process. Other concerns in the diamond industry include working conditions in diamond cutting centers as well as the use of child labor. Both of these concerns come up when considering issues in Surat, India.

Gold

Fairtrade certified gold is used in manufacturing processes as well as for jewellery. The Fairtrade Standard for Gold and Associated Precious Metals for Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining covers the requirements for gold products to identified as "Fairtrade". Silver and platinum are also Fairtrade precious metals.

In February 2011, the United Kingdom's Fairtrade Foundation became the first NGO to begin certifying gold under the fair trade rubric.

Pornography or Sex industry

Fair trade also influences the porn industry. Feminist writers and academics advocate a pornography industry with mutual consent and no exploiting labor conditions for actors and actresses.

Politics

European Union

In 1994, the European Commission prepared the "Memo on alternative trade" in which it declared its support for strengthening fair trade and its intention to establish an EC Working Group on Fair Trade. The same year, the European Parliament adopted the "Resolution on promoting fairness and solidarity in North South trade", voicing its support for fair trade. In 1996, the Economic and Social Committee adopted an "Opinion on the European 'Fair Trade' marking movement". A year later, a resolution adopted by the European Parliament called on the European Commission to support fair trade banana operators, and the European Commission published a survey on "Attitudes of EU consumers to Fair Trade bananas", concluding that Fair Trade bananas would be commercially viable in several EU Member States.

In 1998, the European Parliament adopted the "Resolution on Fair Trade", which was followed by a Commission in 1999 that adopted the "Communication from the Commission to the Council on 'Fair Trade'". In 2000, public institutions in Europe started purchasing Fairtrade Certified coffee and tea, and the Cotonou Agreement made specific reference to the promotion of Fair Trade in article 23(g) and in the Compendium. The European Parliament and Council Directive 2000/36/EC also suggested promoting Fair Trade. In 2001 and 2002, several other EU papers explicitly mentioned fair trade, most notably the 2001 Green Paper on Corporate Social Responsibility and the 2002 Communication on Trade and Development.

In 2004, the European Union adopted "Agricultural Commodity Chains, Dependence and Poverty–A proposal for an EU Action Plan", with a specific reference to the fair trade movement, which has "been setting the trend for a more socio-economically responsible trade." In 2005, in the European Commission communication "Policy Coherence for Development–Accelerating progress towards attaining the Millennium Development Goals", fair trade is mentioned as "a tool for poverty reduction and sustainable development".ent unanimously adopted a resolution on fair trade, recognizing the benefits achieved by the fair trade movement, suggesting the development of an EU-wide policy on fair trade, defining criteria that need to be fulfilled under fair trade to protect it from abuse, and calling for greater support for fair trade. "This resolution responds to the impressive growth of Fair Trade, showing the increasing interest of European consumers in responsible purchasing," said Green MEP Frithjof Schmidt during the plenary debate. Peter Mandelson, EU Commissioner for External Trade, responded that the resolution would be well received at the European Commission. "Fair Trade makes the consumers think and therefore it is even more valuable. We need to develop a coherent policy framework and this resolution will help us."

France

In 2005, French National Assembly member Antoine Herth issued the report "40 proposals to sustain the development of Fair Trade". The report was followed the same year by a law that would establish a commission to recognize fair trade Organisations. In parallel to the legislativents, also in 2006, the French chapter of ISO (AFNOR) adopted a reference document on Fair Trade after five years of discussion.

Italy

In 2006, Italian lawmakers debated how to introduce a law on fair trade in Parliament. A consultation process involving a wide range of stakeholders was launched in early October. A definition of fair trade was developed. However, its adoption is still pending as the efforts were stalled by the 2008 Italian political crisis.

Netherlands

The Dutch province of Groningen was sued in 2007 by coffee supplier Douwe Egberts for requiring its coffee suppliers to meet fair trade criteria, most notably the payment of a minimum price and a development premium to producer cooperatives. Douwe Egberts, which sells coffee brands under self-developed ethical criteria, believed the requirements were discriminatory. After several months of discussions and legal challenges, the province of Groningen prevailed. Coen de Ruiter, director of the Max Havelaar Foundation, called the victory a landmark event: "it provides governmental institutions the freedom in their purchasing policy to require suppliers to provide coffee that bears the fair trade criteria, so that a substantial and meaningful contribution is made in the fight against poverty through the daily cup of coffee".

Criticism

Ethical basis

Studies shows a significant number of consumers were content to pay higher prices for fair trade products, in the belief that this helps the poor. One ethical criticism of Fairtrade is that this premium over non-Fairtrade products does not reach the producers and is instead collected by businesses or by employees of co-operatives, or is used for unnecessary expenses. Some research finds the implementation of certain fair trade standards causes greater inequalities in markets where these rigid rules are inappropriate for the specific market.

What occurs with the money?

Little money may reach the developing countries

The Fairtrade Foundation does not monitor how much retailers charge for fair trade goods, so it is rarely possible to determine how much extra is charged or how much of that premium reaches the producers. In four cases it has been possible to find out. One British café chain was passing on less than one percent of the extra charged to the exporting cooperative; in Finland, Valkila, Haaparanta, and Niemi found that consumers paid much more for Fairtrade, and that only 11.5% reached the exporter. Kilian, Jones, Pratt, and Villalobos talk of U.S. Fairtrade coffee getting US$5 per pound extra at retail, of which the exporter receives only 2%. Mendoza and Bastiaensen calculated that in the UK only 1.6%–18% of the extra charged for one product line reached the farmer. These studies assume that the importers paid the full Fairtrade price, which is not necessarily the case.

Less money reaches farmers

The Fairtrade Foundation does not monitor how much of the extra money paid to the exporting cooperatives reaches the farmer. The cooperatives incur costs in reaching fair trade standards, and these are incurred on all production, even if only a small amount is sold at fair trade prices. The most successful cooperatives appear to spend a third of the extra price received on this: some less successful cooperatives spend more than they gain. While this appears to be agreed by proponents and critics of fair trade, there is a dearth of economic studies setting out the actual revenues and what the money was spent on. FLO figures are that 40% of the money reaching the developing world is spent on "business and production", which would include these costs as well as costs incurred by any inefficiency and corruption in the cooperative or the marketing system. The rest is spent on social projects, rather than being passed on to farmers.

Differing anecdotes state farmers are paid more or less by traders than by fair trade cooperatives. Few of these anecdotes address the problems of price reporting in developing world markets, and few appreciate the complexity of the different price packages that may or may not include credit, harvesting, transport, processing, etc. Cooperatives typically average prices over the year, so they pay less than traders at some times, more at others. Bassett (2009) compares prices only where Fairtrade and non-Fairtrade farmers have to sell cotton to the same monopsonistic ginneries which pay low prices. Prices would have to be higher to compensate farmers for the increased costs they incur to produce fair trade. For instance, fair trade encouraged Nicaraguan farmers to switch to organic coffee, which resulted in a higher price per pound, but a lower net income because of higher costs and lower yields.

Effects of low barriers to entry

A 2015 study concluded that the low barriers to entry in a competitive market such as coffee undermines any effort to give higher benefits to producers through fair trade. They used data from Central America to establish that the producer benefits were close to zero. This is because there is an oversupply of certification, and only a fraction of produce classified as fair trade is actually sold on fair trade markets, just enough to recoup the costs of certification.

Inefficient marketing system

One reason for high prices is that fair trade farmers have to sell through a monopsonist cooperative, which may be inefficient or corrupt–certainly some private traders are more efficient than some cooperatives. They cannot choose the buyer who offers the best price, or switch when their cooperative is going bankrupt if they wish to retain fairtrade status. Fairtrade deviates from the free market ideal of some economists. Brink Lindsey calls fairtrade a "misguided attempt to make up for market failures" that encourages market inefficiencies and overproduction.

Fair trade harms other farmers

Overproduction argument

Critics argue that fair trade harms non-Fairtrade farmers. Fair trade claims that its farmers are paid higher prices and are given special advice on increasing yields and quality. Economists argue that if this is so, Fairtrade farmers will increase production. As the demand for coffee is highly elastic, a small increase in supply means a large fall in market price, so perhaps a million Fairtrade farmers get a higher price and 24 million others get a substantially lower price. Critics cite the example of farmers in Vietnam being paid a premium over the world market price in the 1980s, planting much coffee, then flooding the world market in the 1990s. The fair trade minimum price means that when the world market price collapses, it is the non-fair trade farmers, particularly the poorest, who have to cut down their coffee trees. This argument is supported by mainstream economists, not just free marketers.

Other ethical issues

Secrecy

Under EU law (Directive 2005/29/EC on Unfair Commercial Practices) the criminal offense of unfair trading is committed if (a) "it contains false information and is therefore untruthful or in any way, including overall presentation, deceives or is likely to deceive the average consumer, even if the information is factually correct", (b) "it omits material information that the average consumer needs… and thereby causes or is likely to cause the average consumer to take a transactional decision that he would not have taken otherwise", or (c) "fails to identify the commercial intent of the commercial practice… [which] causes or is likely to cause the average consumer to take a transactional decision that he would not have taken otherwise." Peter Griffiths (2011) points to false claims that fair trade producers get higher prices and to the almost universal failure to disclose the extra price charged for fair trade products, how much of this actually reaches the developing world, what this is spent on in the developing world, how much (if any) reaches farmers, and the harm that fair trade does to non-fair trade farmers. He also points to the failure to disclose when "the primary commercial intent" is to make money for retailers and distributors in rich countries.

Unethical selling techniques

Economist Philip Booth says that the selling techniques used by some sellers and supporters of fair trade are bullying, misleading, and unethical, such as the use of boycott campaigns and other pressure to force sellers to stock a product they think ethically suspect. However, the opposite has been argued, that a more participatory and multi-stakeholder approach to auditing might improve the quality of the process.

Some people argue that strategic use of labeling may help embarrass (or encourage) major suppliers into changing their practices. It may bring to light corporate vulnerabilities that activists can exploit. Or it may encourage ordinary people to get involved with broader projects of social change.

Failure to monitor standards

There are complaints that fair trade standards are inappropriate and may harm producers, sometimes making them work several months more for little return.

Enforcement of standards by Fairtrade was described as "seriously weak" by Christian Jacquiau. Paola Ghillani, who spent four years as president of Fairtrade Labelling Organizations, agreed that "certain arguments carry some weight". There are many complaints of poor enforcement: labourers on Fairtrade farms in Peru are paid less than the minimum wage; some non-Fairtrade coffee is sold as Fairtrade "the standards are not very strict in the case of seasonally hired labour in coffee production." "[S]ome fair trade standards are not strictly enforced." In 2006, a Financial Times journalist found that ten out of ten mills visited had sold uncertified coffee to co-operatives as certified. It reported on "evidence of at least one coffee association that received an organic, Fair Trade or other certifications despite illegally growing some 20 per cent of its coffee in protected national forest land."

Trade justice and fair trade

Segments of the trade justice movement have criticized fair trade for focusing too much on individual small producer groups without advocating for trade policy changes that would have a larger effect on disadvantaged producers' lives. French author and RFI correspondent Jean-Pierre Boris championed this view in his 2005 book Commerce inéquitable.

Political objections

There have been political criticisms of fair trade from the left and the right. Some believe the fair trade system is not radical enough. Christian Jacquiau, in his book Les coulisses du commerce équitable, calls for stricter fair trade standards and criticizes the fair trade movement for working within the current system (i.e., partnerships with mass retailers, multinational corporations, etc.) rather than establishing a new, fairer, fully autonomous (i.e., government monopoly) trading system. Jacquiau also supports significantly higher fair trade prices in order to maximize the effect since most producers only sell a portion of their crop under fair trade terms. It has been argued that the fair trade approach is too rooted in a Northern consumerist view of justice that Southern producers do not participate in setting. "A key issue is therefore to make explicit who possesses the power to define the terms of Fairtrade, that is who possesses the power in order to determine the need of an ethic in the first instance, and subsequently command a particular ethical vision as the truth."