| Public finance |

|---|

|

Monetary reform is any movement or theory that proposes a system of supplying money and financing the economy that is different from the current system.

Monetary reformers may advocate any of the following, among other proposals:

- A return to the gold standard (or silver standard or bimetallism).

- Abolition of central bank support of the banking system during periods of crisis and/or the enforcement of full reserve banking for the privately owned banking system to remove the possibility of bank runs, possibly combined with sovereign money issued and controlled by the government or a central bank under the direction of the government. There is an associated debate within Austrian School whether free banking or full reserve banking should be advocated but regardless Austrian School economists such as Murray Rothbard support ending central bank bail outs ("ending the Fed").

- The issuance of interest-free credit by a government-controlled and fully owned central bank. Such interest-free but repayable loans could be used for public infrastructure and productive private investment. This proposal seeks to avoid debt-free money causing inflation.

- The issuance of social credit – "debt-free" or "pure" money issued directly from the Treasury – rather than the sourcing of fresh money from a central bank in the form of interest-bearing bonds. These direct cash payments would be made to "replenish" or compensate people for the net losses some monetary reformers believe they suffer in a fractional reserve-based monetary system.

Common targets for reform

Of all the aspects of monetary policy, certain topics reoccur as targets for reform:

Reserve requirements

Banks typically make loans to customers by crediting new demand deposits to the account of the customer. This practice, which is known as fractional reserve banking, permits the total supply of credit to exceed the liquid legal reserves of the bank. The amount of this excess is expressed as the "reserve ratio" and is limited by government regulators not to exceed a level which they deem adequate to ensure the ability of banks to meet their payment obligations. Under this system, which is currently practiced throughout the world, the money supply varies with the quantity of legal reserves and the amount of credit issuance by banks.

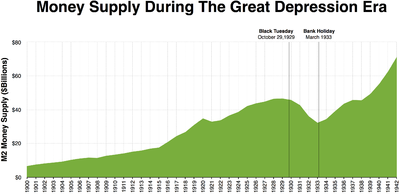

Several major historical examples of financial regulatory reform occurred in the 20th century relating to fractional-reserve banking, made in response to the Great Depression and the many bank runs following the crash of 1929. These reforms included the creation of deposit insurance (such as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation) to mitigate against the danger of bank runs. Countries have also implemented legal reserve requirements which impose minimum reserve requirements on banks. Mainstream economists believe that these monetary reforms have made sudden disruptions in the banking system less frequent.

However, some critics of fractional reserve banking argue that the practice inherently artificially lowers real interest rates and leads to business cycles propagated by excessive capital investment and subsequent contraction. A small number of critics, such as Michael Rowbotham, equate the practice to counterfeiting, because banks are granted the legal right to issue new loans while charging interest on the money thus created. Rowbotham argues that this concentrates wealth in the banking sector with various pernicious effects.

Money creation by the central bank

Some critics discuss the fact that governments pay interest for the use of money which the central bank creates "out of nothing". These critics claim that this system causes economic activity to depend on the actions of privately owned banks, which are motivated by self-interest rather than by any explicit social purpose or obligation.

International organizations and developing nations

Some monetary reformers criticise existing global financial institutions such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, Bank of International Settlements and their policies regarding money supply, banks and debt in developing nations, in that they appear to these writers to be "forcing" a regime of extortionate or unpayable debt on weak Third World governments that do not have the capacity to pay the interest on these loans without severely affecting the well-being or even the viability of the local population. The attempt by weak Third World governments to service external debt with the sale of valuable hard and soft commodities on world markets is seen by some to be destructive of local cultures, destroying local communities and their environment.

Arguments for reform

Among the arguments for a transition to full-reserve banking or sovereign money are as follows:

- Money are created when a loan is made and this money disappear when the loan is paid down. The central banks cannot control the money supply when private banks are creating credit money. Credit money can be converted to reserve money in various ways so that there is no practical limit to the amount of credit money that can be created by private banks. This increases the risk of economic crises, unemployment, and bank bailouts or bank runs.

- Less than 6% of the money in circulation in the world is coins and bank notes, the rest originates from bank credit, carrying interest. This interest allows banks to earn rents from the mere fact that money exist. Reformers do not think it fair that the whole society is paying rents to the banks just for having money to circulate.

- The total amount of public and private debt in the world is now between two and three times the amount of broad money in circulation. This is a result of the accumulated compound interest of credit money. This counterintuitive fact makes it virtually impossible to repay all debt. The mathematical consequence is that somebody will have to go bankrupt even if they have done nothing wrong. It seems unfair that somebody will become destitute as a consequence of the money system rather than because of their own reckless behavior.

- It is not only individual persons and businesses that go

bankrupt as a consequence of the fact that there is more debt than money

in circulation. Many states have gone bankrupt and some states have done so many times. The debt problem is particularly severe for developing countries that have debt in foreign currencies. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank

have been promoting loans to resource-rich developing countries for the

expressed purpose of promoting economic growth in these countries, yet

these loans were denominated in foreign currencies and most of the money

were used for paying transnational entrepreneurs without ever entering

the local economy. These countries have been forced to sell off national

assets in order to service the debt. Also a number of countries in the European Union

are affected when a large part of the money circulating in the country

originates from banks in other member countries. The spiraling,

unpayable national debt has led to social chaos and even war in some cases.

- A major part of all new credit money that is created is spent on changing the ownership of existing assets rather than creating new assets. This process inflates the prices of assets, including real estate, factories, land, and intellectual rights. This makes living unnecessarily costly for everybody. It contributes to growing inequality and it makes the economy unstable because of the creation of asset bubbles.

- The exponentially increasing debt in society can only be serviced as long as the rate of economic growth exceeds the interest rate. This creates an imperative for perpetual growth in production and consumption. This leads to overconsumption and overexploitation of resources. The technological progress in labor-saving technologies has not given us more leisure as we expected, because of the necessary growth in consumption.

- The unpayable debt leads to bankruptcies of homeowners and foreclosure of their homes. This allows banks to replace their virtual assets in the form of money created 'out of thin air' with physical assets in the form of real estate. In 1968, a court in Minnesota decided that this practice was unconstitutional because the process by which the bank had created money from nothing was fraudulent (see First National Bank of Montgomery v. Daly).

Arguments against reform

Among the arguments for keeping the current system of money creation based on the credit theory of money or fractional reserve banking are as follows:

- Switching to an untested banking system that differs from that of other countries would lead to a situation of extreme uncertainty.

- A reform would make it difficult for the central bank to implement a monetary policy that secures price stability.

- The creation of money free of debt would make it difficult for the central bank to later reduce the money supply.

- The central bank would quite likely be subjected to political pressures for producing more money for whatever purpose is high on the political agenda. Giving in to such pressures would lead to inflation.

- The finance sector would be weakened because its profit is reduced.

- A reform would not offer complete protection against financial crises abroad.

- A reform would lead to an unhealthy concentration of power at the central bank. Critics doubt that the central bank can determine the required money supply better than the private banks can.

- The central bank may have to provide credit to commercial banks and accept the accompanying risk.

- A sovereign money system would stimulate the creation of shadow banking and alternative means of payment.

- In the traditional banking system, the central bank controls the interest rate while the money supply is determined by the market. In a sovereign money system, the central bank controls the money supply while the market controls the interest rate. In the traditional system, the need for investments determines the amount of credit that is issued. In a sovereign money system, the amount of saving determines the investments. This change of influences will generate a new and different system with its own dynamics and possible instabilities. The interest rate may fluctuate as well as the liquidity. It is not certain that the market will find an equilibrium where the liquidity is sufficient for the needs of the real economy and full employment.

Alternative money systems

Government Control vs Central Bank independence

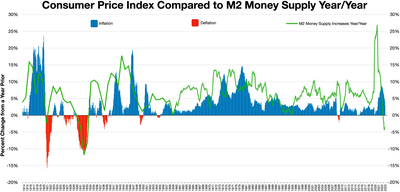

To regulate credit creation, some countries have created a currency board, or granted independence to their central bank. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the Reserve Bank of Australia, the Federal Reserve, and the Bank of England are examples where the central bank is explicitly given the power to set interest rates and conduct monetary policy independent of any direct political interference or direction from the central government. This may enable the setting of interest rates to be less susceptible to political interference and thereby assist in combating inflation (or debasement of the currency) by allowing the central bank to more effectively restrict the growth of M3.

However, given that these policies do not address the more fundamental issues inherent in fractional reserve banking, many suggest that only more radical monetary reform such as government directly taking over central banks such as the China or Swiss models can promote positive economic or social change. Although central banks may appear to control inflation, through periodic bank rescues and other means, they may inadvertently be forced to increase the money supply (and thereby debase the currency) to save the banking system from bankruptcy or collapse during periodic bank runs, thereby inducing moral hazard in the financial system, making the system susceptible to economic bubbles.

International monetary reform

Theorists such as Robert Mundell (and more radical thinkers such as James Robertson) see a role for global monetary reform as part of a system of global institutions alongside the United Nations to provide global ecological management and move towards world peace, with Robert Mundell in particular advocating the revived use of gold as a stabilising factor in the international financial system. Henry Liu of the Asia Times Online argues that monetary reform is an important part of a move towards post-autistic economics.

While some mainstream economists favour monetary reforms to reduce inflation and currency risk and to increase efficiency in the allocation of financial capital, the idea of all-encompassing reform for green or peace objectives is typically espoused by those on the left-wing of the subject and those associated with the anti-globalization movement.

Social credit and the provision of debt-free money directly from government

Still other radical reform proposals emphasise monetary, tax and capital budget reform which empowers government to direct the economy toward sustainable solutions which are not possible if government spending can only be financed with more government debt from the private banking system. In particular, a number of monetary reformers, such as Michael Rowbotham, Stephen Zarlenga and Ellen Brown, support the restriction or banning of fractional-reserve banking (characterizing it as an illegitimate banking practice akin to embezzlement) and advocate the replacement of fractional-reserve banking with government-issued debt-free fiat currency issued directly from the Treasury rather than from the quasi-government Federal Reserve. Austrian commentator Gary North has sharply criticized these views in his writings.

Alternatively, some monetary reformers such as those in the social credit movement, support the issuance of repayable interest-free credit from a government-owned central bank to fund infrastructure and sustainable social projects. This social credit movement flourished briefly in the early 20th century, but then became marginalized. In Canada, it was an important political movement that ruled Alberta through nine legislatures between 1935 and 1971, and also won many seats in Québec. It died out in the 1980s.

Both these groups (those who advocate the replacement of fractional-reserve banking with debt-free government-issued fiat, and those who support the issuance of repayable interest-free credit from a government-owned central bank) see the provision of interest-free money as a way of freeing the working populace from the bonds of "debt slavery" and facilitating a transformation of the economy away from environmentally damaging consumerism and towards sustainable economic policies and environment-friendly business practices.

Examples of government issued debt-free money

Some governments have experimented in the past with debt-free government-created money independent of a bank. The American Colonies used the "Colonial Scrip" system prior to the Revolution, much to the praise of Benjamin Franklin. He believed it was the efforts of English bankers to revoke this government-issued money that caused the Revolution.

Abraham Lincoln used interest-free money created by the government to help the Union win the American Civil War. He is sometimes quoted (probably apocryphally) calling these 'Greenbacks' "the greatest blessing the people of this republic ever had."

Local barter, local currency

Some go further and suggest that wholesale reform of money and currency, based on ideas from green economics or Natural Capitalism, would be beneficial. These include the ideas of soft currency, barter and the local service economy.

Local currency systems can operate within small communities, outside of government systems, and use specially printed notes or tokens called scrips for exchange. Barter takes this further by swapping goods and services directly; a compromise being the Local Exchange Trading Systems (LETS) scheme: a formalised system of community-based economics that records members' mutual credit in a central location.

Commodity money

Some proponents of monetary reform desire a move away from fiat money towards a hard currency or asset-backed currency, which is often argued to be an antidote to inflation. This may involve using commodity money such as money backed by the gold, silver or both, commodities which supporters argue possess unique properties: their extraordinary malleability, their strong resistance to forgery, their character as stable and impervious to decay, and their inherently limited supply.

Digital means are also now possible to allow trading in hard currencies such as gold, and some believe a new free market will emerge in money production and distribution, as the internet allows renewed decentralisation and competition in this area, eroding the central government's and bankers' old monopoly control of the means of exchange.

Free banking

Some monetary reformers favour permitting competing banks to issue private banknotes whilst also eliminating the central bank's role as lender of last resort. In the absence of these factors, they believe a gold standard or silver standard would arise spontaneously out of the free market.